Abstract

Evolutionary novelties have been important in the history of life, but their origins are usually difficult to examine in detail. We previously described the evolution of a novel trait, aerobic citrate utilization (Cit+), in an experimental population of Escherichia coli. Here we analyze genome sequences to investigate the history and genetic basis of this trait. At least three distinct clades coexisted for more than 10,000 generations prior to its emergence. The Cit+ trait originated in one clade by a tandem duplication that captured an aerobically-expressed promoter for the expression of a previously silent citrate transporter. The clades varied in their propensity to evolve this novel trait, although genotypes able to do so existed in all three clades, implying that multiple potentiating mutations arose during the population’s history. Our findings illustrate the importance of promoter capture and altered gene regulation in mediating the exaptation events that often underlie evolutionary innovations.

Evolutionary novelties are qualitatively new traits that open up ecological opportunities and thereby promote diversification1,2. These traits are thought to arise typically by the exaptation of genes that previously encoded other functions2–6 via such processes as domain shuffling7, altered regulation8, and duplication followed by neo-functionalization9,10. Multiple mutations may be necessary to produce the new function9,11, and thus its potential to evolve may be contingent on subtle differences between species, populations, or even genotypes. A complete understanding of the evolution of a novel trait requires explanation of its ecological function, its physiological basis, the underlying mutations, and the history of the accumulated changes2.

Evolution experiments with microorganisms offer unparalleled opportunities to assess the evolution of novel traits12–15. Microbes have rapid generations and large populations, and new technologies allow discovery of mutations throughout their genomes16–19. Samples can be frozen and revived, allowing phylogenies and mutational histories to be constructed and analyzed18,19.

Twelve populations of Escherichia coli have been propagated in the long-term evolution experiment (LTEE) for over 40,000 generations in a glucose-limited minimal medium13. The medium also contains abundant citrate, which is present as a chelating agent20, but E. coli cannot exploit citrate as a carbon and energy source in the well-aerated conditions of the experiment21,22. The inability to grow aerobically on citrate is a long-recognized trait that, in part, defines E. coli as a species23. Spontaneous citrate-using (Cit+) mutants are extraordinarily rare24, but a Cit+ variant evolved in one population (designated Ara–3) around 31,000 generations20. Cit+ cells became dominant after 33,000 generations, although Cit− cells persisted. This shift was accompanied by a several-fold increase in total population size owing to the high concentration of citrate relative to glucose in the medium.

The emergence of the Cit+ trait was contingent upon one or more earlier mutations in the population’s history. When evolution was replayed from clones isolated at various time-points, clones from later generations were more likely to produce Cit+ mutants than did the ancestor and other early clones20. This finding implied that a genetic background evolved that “potentiated” the evolution of this trait. In principle, this effect could involve two distinct mechanisms. One possibility is that the rate of mutation, or certain types of mutation, increased such that the required event was more likely to occur in later generations. The other possibility is an epistatic interaction, such that the expression of a mutation that produced the Cit+ trait required one or more preceding mutations. Here we report the results of extensive whole-genome re-sequencing that allowed us to reconstruct the population’s history, identify mutations underlying the Cit+ phenotype, and elucidate the physiological basis of this novel trait.

Genome sequences and phylogeny

We sequenced 29 clones sampled at various generations from population Ara–3, including 9 Cit+ and 3 Cit− clones known to be potentiated20 (Supplementary Table 1). Mutations including single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) as well as deletions, insertions, and some chromosomal rearrangements were identified (Supplementary Table 2) by comparing reads to the genome of the ancestral strain, REL60625. Inversions and other rearrangements that involved long sequence repeats would have escaped detection.

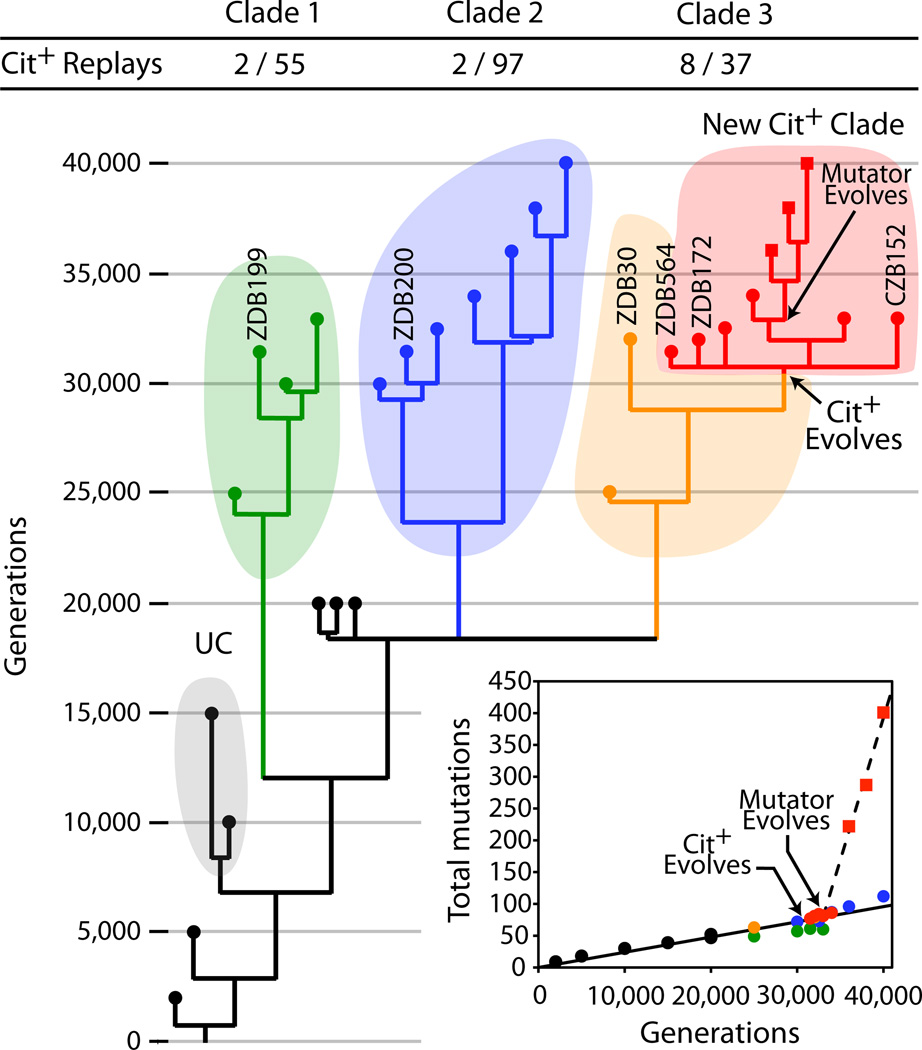

We reconstructed the population’s phylogenetic history from presence-absence matrices of all mutations identified in the sequenced genomes. Figure 1 shows that the population was polymorphic for most of its history. Several clades, each represented by multiple clones, arose before 20,000 generations. One of them, which we call UC (Unsuccessful Clade), was not seen after 15,000 generations. Clades C1, C2, and C3 coexisted through the evolution of Cit+ and beyond. C1 includes four clones, the earliest from generation 25,000, although a molecular clock (Fig. 1, inset) implies that C1 diverged from the ancestor of C2 and C3 before 15,000 generations. C2 and C3 had diverged by generation 20,000. C3 includes both Cit− clones and all the Cit+ clones, though the first Cit+ cells did not arise until ~31,000 generations. Two mechanisms may explain the prolonged coexistence of the Cit− lineages. First, they may all have acquired beneficial mutations without one gaining enough advantage to fix26. Alternatively, they might have filled subtly different niches, such as through the differential use of secreted metabolites27,28.

Figure 1. Phylogeny of Ara–3 population.

Symbols at branch tips mark 29 sequenced clones; labels are shown for clones mentioned in main text and figures. Shaded areas and coloured symbols identify major clades. Fractions above the tree show the number of clones belonging to the clade that yielded Cit+ mutants during replay experiments (numerator) and the corresponding total used in those experiments (denominator). Inset shows number of mutations relative to the ancestor. The solid line is the least-squares linear regression of mutations in non-mutator genomes; the dashed line is the corresponding regression for mutator genomes.

The sequenced Cit+ clones from generation 36,000 and later have a SNP in the mutS gene that produces a premature stop codon and truncates the MutS protein, thereby causing a defect in methyl-directed mismatch DNA repair29. We sequenced mutS from three Cit+ clones from each of generations 33,000, 34,000, 35,000, 36,000, 37,000 and 38,000, and found this SNP in 0, 0, 2, 3 and 3 clones, respectively, indicating that the mutation arose after the origin of the Cit+ lineage. Also, none of the 20 Cit− genomes has this mutation. As a consequence, Cit+ genomes from later generations accumulated SNPs much faster than Cit− and early Cit+ genomes (Fig. 1 inset). Mutator phenotypes evolved in several other populations in the LTEE18,30, so this change was not unique to the Cit+ lineage.

Evolution of the Cit+ function

The evolution of the Cit+ trait involved three successive processes: potentiation, actualization, and refinement. The ancestor’s rate of mutation to Cit+ was immeasurably low, with an upper bound of 3.6 × 10−13 per cell-generation20. Potentiation refers to the evolution of a genetic background in which this function became accessible by mutation. An extremely weak Cit+ variant had emerged by 31,500 generations, which represents the actualization step. The new function was then refined, which allowed the efficient exploitation of citrate, the rise of the Cit+ subpopulation to numerical dominance, and the expansion of the total population size. Of these processes, actualization is the most tractable for study owing to the discrete phenotypic change, and we therefore focused on identifying and characterizing the mutational basis of actualization. With that information in hand, additional analyses then shed new light on the processes of refinement and potentiation.

Actualization of the Cit+ function

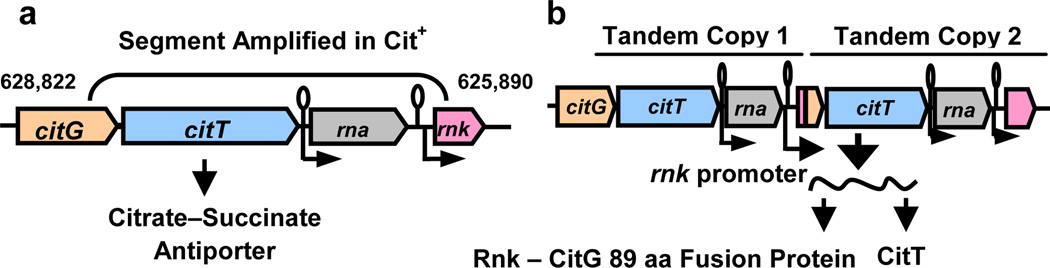

One reason that E. coli cannot grow aerobically on citrate is its inability to transport citrate24,31,32. The origin of the Cit+ phenotype therefore required expression of a citrate transporter. All 9 sequenced Cit+ genomes have two or more tandem copies of a 2933-bp segment that includes part of the citrate fermentation (cit) operon (Fig. 2a). The amplified segment contains two genes: rna, which encodes RNase I33, and citT, which encodes a broad-spectrum C4-di- and tri-carboxylic acid transporter that functions in fermentation as a citrate-succinate antiporter32. The boundary upstream of citT is in the 3' end of the citG gene, which encodes triphosphoribosyl-dephospho-CoA synthase, while the boundary downstream of rna is in the 5' end of rnk, which encodes a regulator of nucleoside diphosphate kinase34. This amplification is not present in the ancestor or any of the sequenced Cit− genomes, and it is only found in population samples after the evolution of the Cit+ lineage (Supplementary Table 3). PCR screens also failed to detect this segment in 27 Cit− clones from generations 33,000 through 40,000, whereas it was found in all 33 Cit+ clones from the same generations (Supplementary Table 4).

Figure 2. Tandem amplification in Cit+ genomes.

a. Ancestral arrangement of citG, citT, rna, and rnk genes. b. Altered spatial and regulatory relationships generated by the amplification.

Amplification mutations can alter the spatial relationship between structural genes and regulatory elements, potentially causing altered regulation and novel traits35–38. The structure of the cit amplification suggested that the Cit+ trait arose from an amplification-mediated promoter capture (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Fig. 1). The amplification joined upstream rnk and downstream citG fragments, producing an rnk-citG hybrid gene expressed from the upstream rnk promoter. Because the citT and citG genes are normally monocistronic, the downstream copy of citT should therefore be co-transcribed with the hybrid gene. If the rnk promoter directs transcription under oxic conditions, then the new rnk-citT regulatory module might allow CitT expression during aerobic metabolism and thereby confer a Cit+ phenotype32.

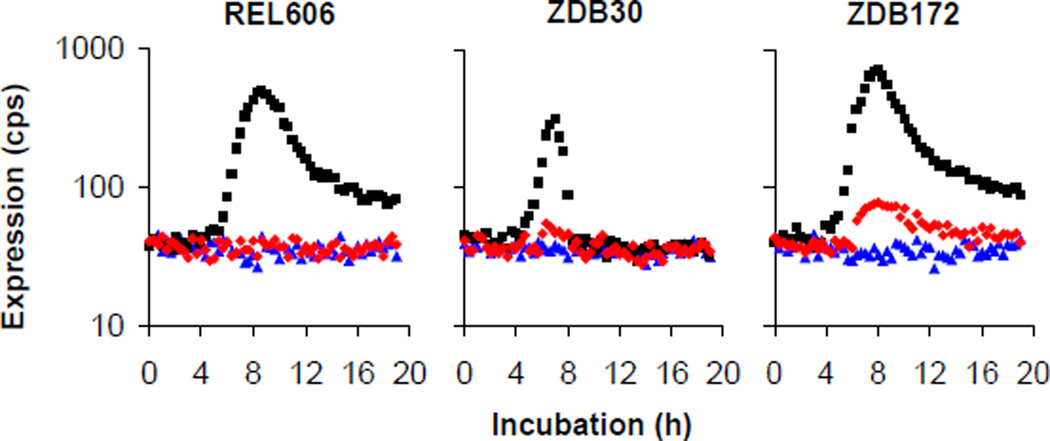

To test this hypothesis, we first examined the capacity of the rnk-citT module to support citT expression in oxic conditions. We constructed a low-copy (1–2 per cell) plasmid, pCDrnk-citTlux, with an rnk-citT module in which citT was replaced by the luxCDABE reporter operon. We made two other plasmids, pCDrnklux and pCDcitTlux, where the reporter was under the control of the native upstream regulatory regions of rnk and citT, respectively. We transformed each plasmid into REL606, the ancestral strain; ZDB30, a potentiated C3 clone from generation 32,000; and ZDB172, a weakly Cit+ clone from generation 32,000. We measured expression (light production) during growth and stationary phase under oxic conditions (Fig. 3). The native citT regulatory region showed no expression (above background) in any strain, indicating that citT is normally silent under oxic conditions. The native rnk regulatory region was expressed in all three strains, with a peak around the transition into stationary phase. Expression from the evolved rnk-citT module was much weaker, but there were small spikes in expression in ZDB30 and ZDB172 coincident with peak expression from the native rnk regulatory region. These results indicate that the rnk-citT module can support citT expression during aerobic metabolism.

Figure 3. Expression levels from native citT, native rnk, and evolved rnk-citT regulatory regions during aerobic metabolism.

Average timecourse of expression for the ancestral strain REL606 (left) and evolved clones ZDB30 (center) and ZDB172 (right), each transformed with reporter plasmids pCDcitTlux (blue), pCDrnklux (black) and pCDrnk-citTlux (red). Each curve shows the average of four replicates.

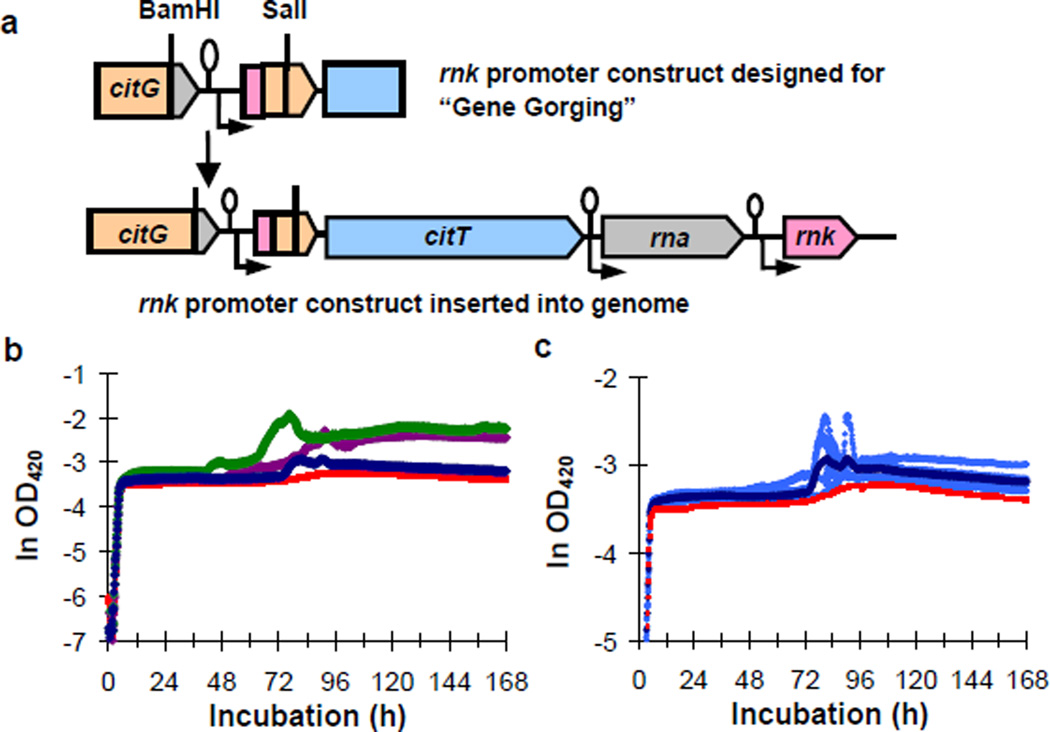

This hypothesis also predicts that the introduction of the rnk-citT module should confer a Cit+ phenotype, while the loss of the cit amplification should cause reversion to a Cit− state. We tested whether the rnk-citT module confers a Cit+ phenotype by inserting a single copy of an amplification fragment containing the rnk promoter immediately upstream of the chromosomal copy of citT (Fig. 4a) in potentiated clone ZDB30. This construct, ZDB595, indeed has a Cit+ phenotype, although it is extremely weak, similar to the earliest evolved Cit+ variants (Fig. 4b). In the same medium used in the LTEE, ZDB595 experienced a lag of >60 hours after glucose depletion, followed by a short period of abortive and inconsistent growth on citrate (Fig. 4b,c). These data imply that the initial Cit+ type was too weak to allow exploitation of citrate under the daily-transfer regime of the LTEE. Nonetheless, ZDB595 had a small (1.0%) but significant competitive advantage over ZDB30 in the same environment (n = 10, t = 3.09, two-tailed P = 0.0128). We also isolated 13 Cit− revertants of a 33,000-generation Cit+ clone, CZB154. All had lost the cit amplification based on both PCR and Southern blot analyses (Supplementary Fig. 2), further supporting the hypothesis that the amplification event had produced the Cit+ phenotype.

Figure 4. New rnk-citT module confers Cit+ phenotype in potentiated background.

a. Engineered construct containing the cit amplification junction with the rnk promoter, and the arrangement following its insertion into the chromosome. b. Average growth trajectories in DM25 of potentiated clone ZDB30 (red), its isogenic construct with chromosomal integration of the rnk-cit module ZDB595 (blue), 31,500-generation Cit+ clone ZDB564 (purple), and 32,000-generation Cit+ clone ZDB172 (green). c. Trajectories of ZDB595 compared to its parent. Light blue trajectories show heterogeneity among replicate cultures of ZDB595; dark blue and red are averages for ZDB595 and its parent, ZDB30, as in panel b (except different scale).

Refinement of the Cit+ function

Given the extremely weak initial Cit+ phenotype, additional mutations must have refined the new function. Refinement is an open-ended process, and we focus only on early refining mutations that led to the rise of Cit+ cells to high frequency and the concurrent expansion of the population. These mutations are evidenced by the improvement on citrate of Cit+ clones isolated between 31,500 and 33,000 generations (Supplementary Fig. 3). We examined the genomes of the five sequenced Cit+ clones from before the population expansion, including one from generations 31,500, 32,000 and 32,500 and two from generation 33,000. We focused on the mutations on the line of descent for the Cit+ subpopulation, where that line is defined by the presence of the same mutations in clones from generations 34,000, 36,000 and 38,000 (Supplementary Tables 5–8). Two SNPs and one IS-element insertion were present in only one of the 33,000-generation genomes. The IS insertion and one SNP appear unrelated to growth on citrate. The remaining SNP is in the regulatory region of dctA, which encodes a transporter of succinate and other C4-di-carboxylic acids39. This mutation may improve recovery of succinate exported in exchange for citrate. However, the other 33,000-generation clone grew better on citrate (Supplementary Fig. 3). Thus, the dctA mutation does not appear to be responsible for the population expansion, although it might have been advantageous to its carriers.

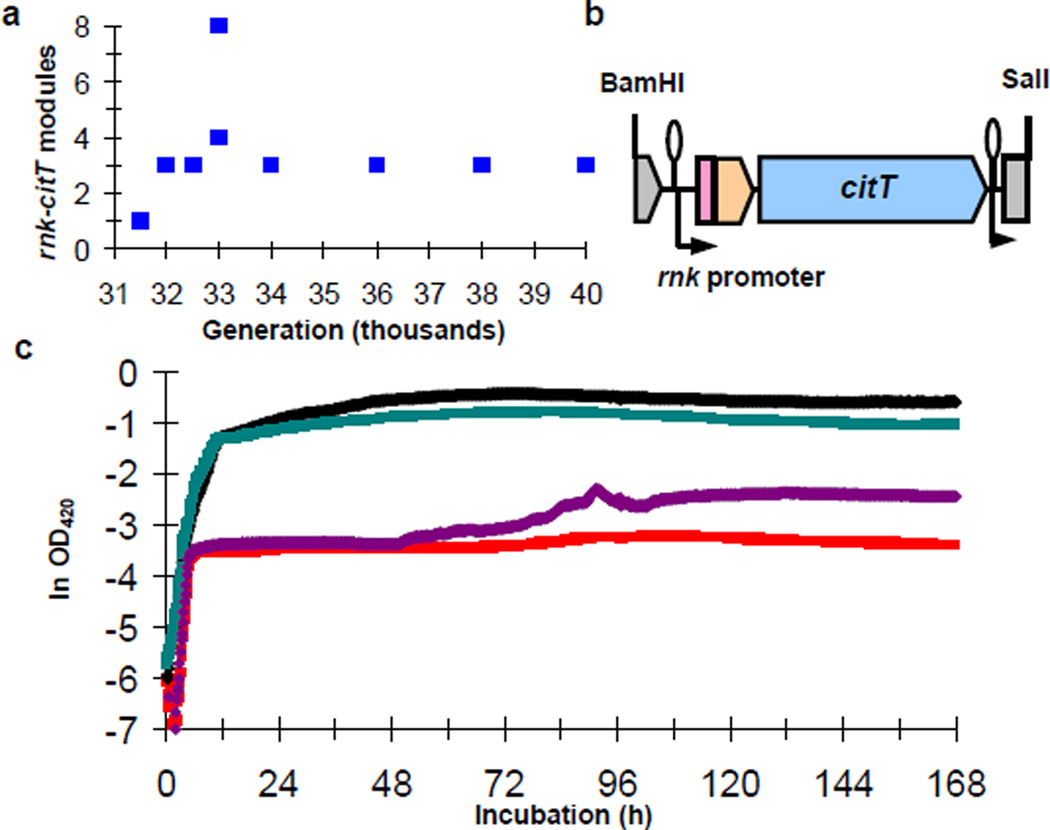

These early Cit+ genomes also show increases in cit copy number. The earliest one had a tandem duplication, whereas later genomes had a three-copy tandem array within a larger tandem duplication, a four-copy tandem array, a tandem duplication in a larger three-copy tandem array, and a nine-copy tandem array (Supplementary Table 9). Changes in amplification copy number readily occur by recombination, and they have been implicated in the refinement of other weak functions40,41. These changes increased the number of rnk-citT modules relative to the earliest Cit+ genome (Fig. 5a) and presumably increased the expression of CitT as well. To test whether an increased number of rnk-citT modules could have caused the population expansion, we cloned the module (Fig. 5b) into the high-copy plasmid pUC1942 and moved the resulting plasmid, pZBrnk-citT, into the potentiated clone ZDB30. The resulting strain, ZDB612, is strongly Cit+, rapidly transitions from glucose to citrate, and grows similarly to the 33,000-generation clone CZB152 (Fig. 5c). The increased number of rnk-citT modules can thus explain the refinement of the Cit+ phenotype that allowed the population expansion.

Figure 5. Refinement of Cit+ phenotype by increased number of rnk-citT modules.

a. Change in rnk-citT module copy number in sequenced Cit+ clones over time. b. Structure of rnk-citT module cloned into high-copy plasmid pUC19 to produce pZBrnk-citT. c. Growth trajectories in DM25 of potentiated Cit− clone ZDB30 (red), 31,500-generation Cit+ clone ZDB564 (purple), 33,000-generation Cit+ clone CZB152 (black), and ZDB612, a pZBrnk-citT transformant of ZDB30 (green). Each trajectory is the average of six replicates.

In contrast to the early variation in cit amplification, later Cit+ genomes have four-copy tandem arrays (Fig. 5a). Amplifications tend to be unstable40,41, and further refinement may have favored stable mutations. The evolution of the mutator phenotype in the Cit+ lineage complicates efforts to identify these later refining mutations, but some interesting candidates include SNPs in citT itself; gltA, which encodes citrate synthase; and aceA, which encodes isocitrate lyase.

Potentiation of Cit+ evolution

Before the Cit+ trait could evolve, the Ara–3 population had to evolve a genetic background in which that new function was accessible by mutation. Potentiation was demonstrated by ‘replay’ experiments using 270 clones sampled over the population’s history20. The replays produced 17 Cit+ mutants that derived from 13 clones, all from generation 20,000 or later. Fluctuation tests confirmed that potentiated clones had increased mutation rates to Cit+, although such mutations were still extremely rare20.

Phylogeny implies multiple potentiating mutations

The potentiating mutations are not known to confer any phenotype amenable to screening, so there is no simple way to distinguish between potentiated and non-potentiated clones. Instead, we examined the distribution of the 13 potentiated clones identified by the replay experiments using mutations (Supplementary Table 10) that differentiated clades UC, C1, C2 and C3 (Fig. 1). We also determined the distribution of the other 256 evolved clones used in the replays to assess the coverage of the clades in those experiments (Supplementary Fig. 4). Overall, 205 clones were assigned to clades, including 12 potentiated clones (Supplementary Table 11). Sixteen from generations 15,000 and earlier were in clade UC. The others came from generations 20,000 and later including 55 in C1, 97 in C2, and 37 in C3. Potentiated clones occurred in all three with 8 in C3 and 2 each in C1 and C2. Nonetheless, this distribution is highly non-random (two-tailed Fisher’s exact test comparing C3 with C1 and C2 combined, P = 0.0003; that test shows no difference between C1 and C2, P = 0.6206). These data, and the absence of any Cit+ mutants generated by the ancestor, imply that potentiation involved at least two mutations, with one arising before these three clades diverged and another in C3 (Fig. 1).

Alternative hypotheses

Two distinct mechanisms might explain the potentiation effect. One is epistasis, whereby an interaction between the potentiating background and the actualizing mutation is needed to express the Cit+ phenotype. The second is that the background physically promoted the final mutation; for example, a later rearrangement may require some prior genomic rearrangement. If expression of Cit+ required earlier mutations, then the rnk-citT module should confer a weaker Cit+ phenotype in a non-potentiated background than a potentiated background. Alternatively, if potentiation facilitated the amplification event itself, then that module should produce an equally strong Cit+ phenotype in both potentiated and non-potentiated backgrounds.

Evidence for epistasis

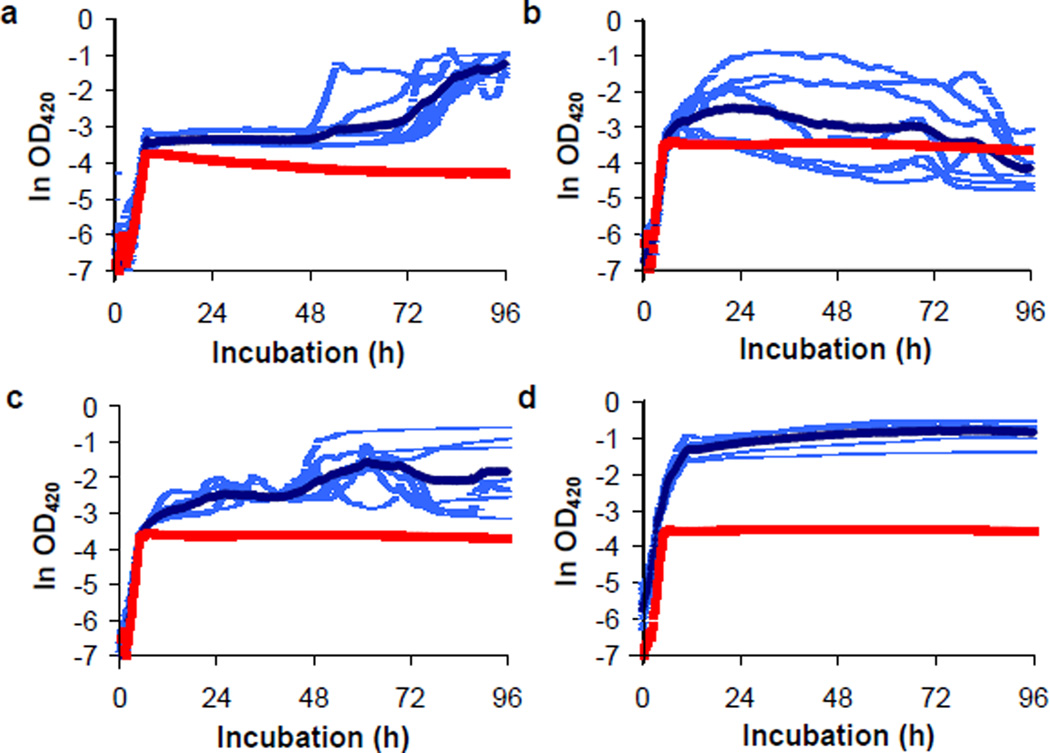

To test these predictions, we first tried to move the single-copy rnk-citT module into the ancestral chromosome, but several attempts were unsuccessful. This outcome is not surprising under the epistasis hypothesis; a key step was screening potential recombinants for citrate use, and the single-copy module conferred an extremely weak Cit+ phenotype even in a potentiated C3 clone (Fig. 4). Instead, we moved plasmid pZBrnk-citT into the ancestor and clones from clades C1, C2, and C3, and examined their growth trajectories (Fig. 6). All four transformants grew on citrate after depleting the glucose. However, transformants of the ancestor and C1 and C2 clones grew poorly on citrate, even with this high-copy plasmid, as evidenced by long lags while transitioning from glucose to citrate, low yields, and inconsistent trajectories across replicates (Fig. 6a–c). By contrast, ZDB612, the transformant of a potentiated C3 clone, grew much faster, more extensively, and consistently across replicates (Fig. 6d). These differences demonstrate epistatic interactions between the rnk-citT module and mutations that distinguish the backgrounds.

Figure 6. Evidence for epistatic interactions in potentiation of Cit+ phenotype.

Growth trajectories in DM25 of diverse clones transformed with the pZBrnk-citT plasmid. a. Ancestral strain REL606 and its transformant ZDB611. b. Clade C1 clone ZDB199 and its transformant ZDB614. c. C2 clone ZDB200 and its transformant ZDB615. d. C3 clone ZDB30 and its transformant ZDB612. Red and dark blue trajectories are averages for the parent clone and its transformant; light blue trajectories show the replicates for the transformant.

These data also support the phylogenetic association between clade C3 and the strength of potentiation in the replay experiments. We examined C3 for candidate mutations that may contribute to potentiation. A mutation in arcB, which encodes a histidine kinase43, is noteworthy because disabling that gene up-regulates the TCA cycle44. That mutation might interact with the rnk-citT module by allowing efficient use of citrate that enters the cell via the CitT transporter. We tried repeatedly to move the evolved and ancestral arcB alleles between strains to test this hypothesis, but without success. In any case, the profound differences in growth trajectories on citrate enabled by the high-copy plasmid (Fig. 6) support the hypothesis that potentiation depends, at least partly, on epistasis between the genetic background and the amplification mutation that generated that module.

Evidence against physical-promotion hypothesis

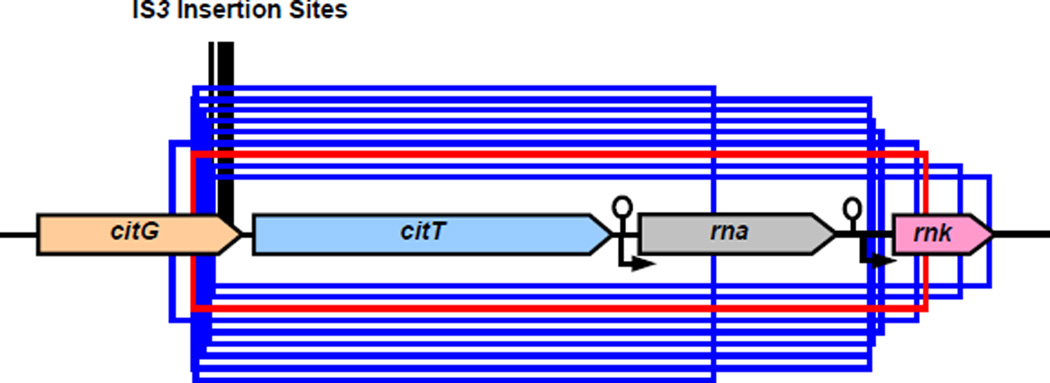

We examined the Cit+ mutants from the replay experiments20 for additional evidence on the nature of potentiation. The physical-promotion hypothesis predicts that these mutants should have cit amplifications similar or identical to the original one. If epistatic interactions enhanced citT expression only from the rnk promoter, then the prediction would be the same. However, if epistasis operated at some broader physiological level, then the replays should have diverse mutations that share only the property that they enable expression of the citrate transporter in the oxic environment of the LTEE. We examined 19 re-evolved Cit+ mutants to identify the relevant mutations; the citT region was examined in all of them, and the genomes of six were sequenced. All have mutations affecting citT, and most clearly put that gene downstream of a new promoter (Supplementary Table 12). Four sequenced Cit+ mutants were derived from Cit− clones that were also sequenced. Besides citT-related mutations, these sequenced mutants had 1–3 other mutations; no gene was mutated in multiple cases, and none appear related to citrate use (Supplementary Table 13), supporting the inference that the citT mutations were responsible for all of the re-evolved Cit+ phenotypes.

The Cit+ mutants arose by diverse mutational processes (Supplementary Table 12). Eight have citT duplications similar to the original one, though no two share the same boundaries (Fig. 7). In seven of these, the duplications generated alternative versions of the rnk-citT module; in the other, the second citT is downstream of the rna promoter. Six mutants have an IS3 element inserted in the 3' end of citG (Fig. 7). IS3 carries outward-directed promoter elements that can activate adjacent genes27,45. Two mutants have large duplications encompassing all or part of the cit operon. One mutant has a large inversion that places most of that operon downstream of the promoter for the fimbria regulatory gene fimB, and another has a deletion in citG that presumably formed a new promoter. Also, most of these mutants have stronger phenotypes (Supplementary Fig. 5) than the earliest Cit+ clones in the main experiment (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Fig. 3). In any case, this new function arose in potentiated backgrounds by a variety of mutational processes that recruited several different promoters to allow CitT expression during aerobic metabolism. Thus, these data do not support the physical-promotion hypothesis, whereas the strain-specific differences in growth on citrate conferred by the rnk-citT module provide clear and compelling evidence for epistasis (Fig. 6). However, these hypotheses are not mutually exclusive, and we cannot reject the possibility that some mutation rendered the genome (or the affected region) more prone to physical rearrangements (including mobile-element insertions) and thereby also contributed to the overall potentiation effect.

Figure 7. Mutations that produced Cit+ phenotype in 14 replay experiments.

The red box shows the boundaries of the 2,933-bp amplified segment that actualized the Cit+ function in the original long-term population. Blue boxes show citT-containing regions amplified in 8 replays that produced Cit+ mutants. Vertical black lines mark 5 locations where IS3 insertions produced Cit+ mutants in 6 other replays.

Perspective

The evolution of citrate-utilization in an experimental E. coli population provided an unusual opportunity to study the multi-step origin of a key innovation. Comparative studies have shown that gene duplications play an important creative role in evolution by generating redundancies that allow neo-functionalization5,6,8,9,10. Our findings highlight the less-appreciated capacity of duplications to produce new functions by promoter capture events that change gene-regulatory networks38. The evolution of citrate-use also highlights that such actualizing mutations are only part of the process by which novelties arise. Before a new function can arise, it may be essential for a lineage to evolve a potentiating genetic background that allows the actualizing mutation to occur or the new function to be expressed. Finally, novel functions often emerge in rudimentary forms that must be refined to exploit the ecological opportunities. This three-step process—in which potentiation makes a trait possible, actualization makes the trait manifest, and refinement makes it effective—is likely typical of many new functions.

METHODS

Evolution experiment

The long-term experiment is described in detail elsewhere13,46. In brief, twelve populations of E. coli B were started in 1988 and have evolved since under conditions of daily 100-fold dilutions in a minimal medium, DM25, containing 139 µM glucose and 1700 µM citrate46. The populations undergo ~6.64 generations per day and had been evolving for 40,000 generations when this study began. Every 500 generations, samples were frozen at –80°C with glycerol as a cryoprotectant. The focus of this study was population Ara–3, in which the ability to grow aerobically on citrate evolved by 31,500 generations20.

Genomic DNA isolation

Clones were revived from frozen stocks by overnight growth in LB medium at 37°C with aeration. DNA was extracted and purified using the Qiagen Genomic-tip 100/G kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany).

Whole-genome sequencing and mutation detection

Clones were sequenced on Illumina GA, GA II, and GA IIx instruments. The resulting reads were deposited in the NCBI SRA database (SRA026813). Most datasets contain single-end reads only, but additional mate-paired libraries were obtained for ZDB30 and ZDB172. Reads were mapped to the reference genome of the ancestral strain (REL606)25, and mutations were predicted using the breseq computational pipeline47. This pipeline detects point mutations, deletions, and new sequence junctions that may indicate IS-element insertions or other rearrangements, as described in its online documentation. Large duplications and amplifications were predicted manually by examining the depth of read coverage across each genome.

Mutation lists (Supplementary Table 2) were further refined by manually reconstructing the most plausible series of events generating the observed differences. This procedure involved: (1) splitting predicted changes into multiple mutations based on phylogenetic relationships, (2) assigning mutations to genomes when a subsequent mutational event prevented their detection (e.g., a SNP within a later deletion), and (3) correcting false-positives for a handful of difficult-to-predict mutations by examining alignments and coverage in all clones. After these procedures, 17 homoplasies remained in the phylogeny, most of which appear to indicate mutational hot-spots: 9 are IS-element insertions at specific sites, 7 are insertions or deletions at the boundaries of IS elements, and only 1 is a single-base substitution not associated with an IS-element. Given these signatures, it is likely that most or all of these mutations occurred independently in multiple lineages.

The copy number and configuration of the citT module were estimated from the number of reads overlapping the new rnk-citT sequence junction relative to the two original flanking-sequence junctions, and from the average read-depth in this region relative to a single-copy region (Supplementary Table 9).

Phylogenetic analysis

An initial parsimony-based tree was calculated using presence-absence data for all mutational events in each genome using the dnapars program from PHYLIP. Branch lengths were recalculated using an irreversible Camin-Sokal model48, because the ancestral states are known and reversions unlikely given the genome size and number of mutations observed. A maximum-likelihood model was then used to estimate branching times and two mutation rates, one for non-mutator branches and one for mutator branches. The model fixed the generation when each clone was sampled and assumed that mutations accumulated on branches according to a Poisson process.

Ten mutations in nine genes (ybaL, nadR, hemE, cspC, yaaH, leuA, tolR, arcB, and gltA) were identified as phylogenetically informative based on their association with particular clades in the Ara–3 population (Supplementary Table 10). Sanger sequencing of PCR-amplified gene fragments was used to determine the presence or absence of these mutations in replay clones, which were then mapped onto the phylogeny using the keys in Supplementary Figure 4. Owing to the large number of clones and genes under consideration, not all genes were sequenced for all clones. Supplementary Table 11 shows the data and phylogenetic assignments. Supplementary Table 14 shows the primer pairs used to amplify each locus.

PCR screens for cit amplifications

The cit amplification was detected in population samples and clones by PCR amplification across the rnk-citG junction using outward-directed primers specific to citT (Supplementary Table 14). When screening population samples, three reactions were run for each time point, and the template was a 1:10 dilution of the frozen sample for that generation.

Expression experiments

Expression was measured using luciferase-based reporter constructs. The complete upstream regions for the native citT and rnk genes were PCR-amplified from the cognate reporters from the E. coli transcriptional library50 using the primers pZE05 and pZE07. The intergenic region of the evolved rnk-citT module was amplified from Cit+ clone ZDB172 using primers nctForward and nctReverse (Supplementary Table 14). The PCR products were cloned into the low-copy (1–2) plasmid pCS26-pac, which contains a kanamycin-resistance gene and the luciferase operon (luxCDABE)49. Each plasmid was transformed into clones REL606, ZDB30 and ZDB172.

Prior to the expression assays, strains were grown in a 96-well plate (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA, USA) in 200 µL per well of DM25 supplemented with 50 µg/mL kanamycin, with constant shaking at 37°C for two 24-h cycles for acclimation. Fresh overnight cultures were then diluted 100-fold into a black, clear-bottomed 96-well plate (9520 Costar; Corning, Lowell, MA, USA), with 150 µL per well of DM25, and covered with breathable sealing membrane (Nunc, Rochester, NY, USA) to prevent evaporation. Light emission was measured using a Wallac Victor2 plate reader (Perkin Elmer Life Sciences, Boston, MA, USA) every 20 min for 19 h with 90 s of 2-mm orbital shaking before each reading. Assays were run in quadruplicate in the same plate.

Isogenic strain construction

A single-copy chromosomal rnk-citT module was placed in a Cit− background using the “gene gorging” method51. Owing to problems inherent to the manipulation of amplified genes, we did not attempt to move an entire citT amplification segment. Instead, we engineered a cit amplification junction containing the rnk promoter from three smaller fragments that were PCR-amplified from the 32,000-generation Cit+ clone ZDB172. The first fragment contained the cit amplification junction (citAmpJ), including the rnk promoter region, and was PCR-amplified using the primers citTAmpJ F and citTAmpJ R (Supplementary Table 14). The second fragment contained the citT-citG junction (citT-citG) and was PCR-amplified using the primers citT-citG F and citT-citG R. The third fragment contained sequence internal to the citG gene (citGfrag) and was PCR-amplified using citGfrag F and citGfrag R. Each primer pair was designed with restriction sites that allowed ligation of the fragments to a hybrid construct in which the cit amplification junction, including the rnk promoter, was embedded within >500 bp of citG flanking sequence. The assembled module was then PCR-amplified using citT-citG Gorge F and citGfrag R (Supplementary Table 14). The forward primer incorporated an I-Sce-I restriction site required for the gene-gorging procedure, which was then performed as described elsewhere51. We screened for putative transformants by performing PCR and testing for a Cit+ phenotype based on a positive reaction on Cristensen’s Citrate Agar52. Successful constructs were confirmed by Sanger sequencing.

Growth trajectories

Strains of interest (Supplementary Table 15) were revived from frozen stocks by growing them in LB, and they were then acclimated by two 24-h culture cycles in DM25. Next, 100 µL of each culture was diluted into 9.9 mL of DM25, and 200 µL aliquots were placed into randomly assigned wells in a 96-well plate. For all pZBrnk-citT transformants, the medium was supplemented with 100 µg/mL ampicillin to ensure plasmid retention. Growth trajectories were replicated 6- to 8-fold for each strain. To limit evaporation, strains were grown in the innermost 60 wells, while the outermost 36 wells were filled with 300 µL of saline buffer. When assays ran longer than 96 h, the buffer was replenished after 96 h. OD420 was measured every 10 min by a VersaMax automated plate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Plates were shaken orbitally for 5 s before each measurement, but were otherwise stationary.

Fitness assays

Relative fitness was measured in competition experiments described elsewhere46. In brief, we inoculated 0.05 mL each of acclimated cultures of ZDB595 and ZDB63, an Ara+ mutant of ZDB30, into 9.9 mL of DM25 with 10-fold replication. Initial densities were measured by dilution plating on tetrazolium arabinose (TA) plates, on which ZDB595 and ZDB63 made red and white colonies, respectively. The cultures were then propagated for three daily transfer cycles, and the final densities were measured using TA plates. Relative fitness was calculated as the ratio of the realized growth rates of the competitors over the course of the experiment46.

Isolation of Cit− revertants

Three 10-mL LB broth cultures were inoculated with 15 µL from the frozen stock of 33,000-generation Cit+ clone CZB154. After overnight growth at 37°C, the cultures were diluted 106-fold, and 100 µL was transferred to ten flasks containing 9.9 mL of three media: DM25, DM25 except without citrate, and M9 broth (a citrate-free minimal medium) with 25 µg/mL glucose. The 30 cultures were incubated at 37°C, and propagated through six daily 1:100 serial dilutions. Each culture was then diluted 104-fold, and 100 µL were spread onto each of eight TA plates. The plates were incubated for ~24 h at 37°C, and colonies were patched onto TA and Minimal Citrate (MC) plates. Clones that grew on TA plates, but not on MC plates, were then streaked onto Christensen’s agar. Those clones that did not produce a Cit+ reaction on Christensen’s agar were retained as Cit− revertants. Up to 512 colonies per replicate culture were tested for loss of the Cit+ phenotype, but only one Cit− revertant was retained from any culture. Cit− revertants were found in 8/10 citrate-free DM25 cultures and in 5/10 cultures containing M9 medium. No revertants were isolated from any cultures in normal DM25 medium, presumably because of the advantage that Cit+ cells have when citrate is present. The 13 Cit− revertants were tested for the presence or absence of the cit amplification by performing both PCR with the citTout F/R primer pair and citT-specific Southern blotting with EcoRV-digested genomic DNA (Supplementary Figure 2, Supplementary Table 14).

Plasmid construction

A DNA fragment containing the complete rnk-citT module was PCR-amplified from Cit+ clone ZDB172 using primers citTAmpX F and citTAmpX R (Supplementary Table 14). The fragment was then inserted into the cloning site of pUC19 (NEB, Ipswich, MA, USA), and sequencing confirmed that the resulting plasmid, pZBrnk-citT, had the corresponding region. The plasmid was transformed into strains REL606, ZDB30, ZDB199 and ZDB200. Cit+ transformants were identified by positive reactions on Cristensen’s Citrate Agar52.

Identification of mutations in Cit+ replays

Nineteen Cit+ mutants isolated in replay and related experiments20 were analyzed for mutations. The mutants were first checked for large changes in the citT region by Southern hybridization with citT-specific probes. Genomic DNA was digested with EcoRV (NEB, Ipswich, MA, USA); fragments were separated on 0.8% agarose gels with a 1-kb ladder (NEB, Ipswich, MA, USA), then transferred to nylon membranes. Hybridizations were performed at 68°C. The citT-specific probe was an internal fragment amplified by PCR using primers in Supplementary Table 14, purified using an Illustra GFX PCR DNA purification kit (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, UK), and labeled using the DIG DNA labeling and detection kit (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Most, but not all, mutants had enlarged citT bands. We tried to PCR-amplify across possible amplification boundaries of each mutant using the same outward-directed citT primers used to screen for the original amplification in the Ara–3 population (Supplementary Table 14). PCR products were thus obtained for 8 clones. Sanger sequencing of the products showed novel junctions consistent with amplifications similar, but not identical, to the original case. For 7 other clones, PCR products of altered size were obtained when the region immediately upstream of citT was amplified, and sequencing showed that each alteration was caused by either a small deletion or an IS3 insertion in citG. To identify mutations at other loci, as well as mutations affecting the cit region, we sequenced the genomes of six mutants, as described above. These genomes included three of the four mutants for which the mutations conferring the Cit+ trait were not resolved using the approaches described above.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank N. Hajela, M. Kauth and S. Sleight for assistance, J. Meyer and J. Plucain for discussion, and C. Turner for comments on the paper. Sequencing services were provided by the MSU Research Technology Support Facility. We acknowledge support from the US National Science Foundation (DEB-1019989 to R.E.L.) including the BEACON Center for the Study of Evolution in Action (DBI-0939454), the US National Institutes of Health (K99-GM087550 to J.E.B.), the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (HR0011-09-1-0055 to R.E.L.), a Rudolf Hugh Fellowship (to Z.D.B.), a DuVall Family Award (to Z.D.B.), a Ronald M. and Sharon Rogowski Fellowship (to Z.D.B.), and a Barnett Rosenberg Fellowship (to Z.D.B).

Footnotes

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Author Contributions J.E.B. and Z.D.B performed genome sequencing and analyses. J.E.B. performed phylogenetic analyses and developed code for sequence analyses. Z.D.B. performed growth curves, molecular experiments, and sequenced specific genes. C.J.D. performed gene-expression experiments. R.E.L. conceived and directs the long-term experiment. Z.D.B., J.E.B., C.J.D. and R.E.L. analyzed data, wrote the paper, and prepared figures.

All genome data have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive database (SRA026813). Other data have been deposited in the DRYAD database (http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.8q6n4).

The authors report no competing financial interests. R.E.L. will make strains available to qualified recipients, subject to a material transfer agreement that can be found at www.technologies.msu.edu/inventors/mta-cda/mta/mta-forms.

References

- 1.Mayr E. The emergence of evolutionary novelties. In: Tax S, editor. Evolution after Darwin. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pigliucci M. What, if anything, is an evolutionary novelty? Philos. Science. 2008;75:887–898. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jacob F. Evolution and tinkering. Science. 1977;196:1161–1166. doi: 10.1126/science.860134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacob F. The Possible and the Actual. Seattle: Univ. Washington Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gould SJ, Vrba ES. Exaptation – a missing term in the science of form. Paleobiol. 1982;8:4–15. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor JS, Raes J. Duplication and divergence: the evolution of new genes and old ideas. Annu. Rev. Genetics. 2004;38:615–643. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.38.072902.092831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patthy L. Genome evolution and the evolution of exon-shuffling – a review. Gene. 1999;238:103–114. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00228-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.True JR, Carroll SB. Gene co-option in physiological and morphological evolution. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2002;18:53–80. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.18.020402.140619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang J. Evolution by gene duplication: an update. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2003;18:282–298. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bergthorsson U, Andersson DI, Roth JR. Ohno's dilemma: evolution of new genes under continuous selection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:17004–17009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707158104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lenski RE, Ofria C, Pennock RT, Adami C. The evolutionary origin of complex features. Nature. 2003;423:139–144. doi: 10.1038/nature01568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elena SF, Lenski RE. Evolution experiments with microorganisms: the dynamics and genetic bases of adaptation. Nature Rev. Genet. 2003;4:457–469. doi: 10.1038/nrg1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lenski RE. Phenotypic and genomic evolution during a 20,000-generation experiment with the bacterium Escherichia coli. Plant Breeding Rev. 2004;24:225–265. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beaumont HJE, Gallie J, Kost K, Ferguson GC, Rainey PB. Experimental evolution of bet hedging. Nature. 2009;462:90–93. doi: 10.1038/nature08504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meyer JR, Dobias DT, Weitz JS, Barrick JE, Lenski RE. Repeatability and contingency in the evolution of a key innovation in phage lambda. Science. 2012;335:428–432. doi: 10.1126/science.1214449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bentley DR. Whole-genome resequencing. Curr. Opin. Genetics. Dev. 2006;16:545–552. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hegreness M, Kishony R. Analysis of genetic systems using experimental evolution and whole-genome sequencing. Genome Biol. 2007;8:201. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-1-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barrick JE, et al. Genome evolution and adaptation in a long-term experiment with E. coli. Nature. 2009;461:1243–1247. doi: 10.1038/nature08480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barrick JE, Lenski RE. Genome-wide mutational diversity in an evolving population of Escherichia coli. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 2009;74:1–11. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2009.74.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blount ZD, Borland CZ, Lenski RE. Historical contingency and the evolution of a key innovation in an experimental population of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:7899–7906. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803151105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koser SA. Correlation of citrate-utilization by members of the colon-aerogenes group with other differential characteristics and with habitat. J. Bacteriol. 1924;9:59–77. doi: 10.1128/jb.9.1.59-77.1924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lutgens M, Gottschalk G. Why a co-substrate is required for anaerobic growth of Escherichia coli on citrate. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1980;199:63–70. doi: 10.1099/00221287-119-1-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scheutz F, Strockbine NA, Genus I. Escherichia, Castellani and Chalmers 1919. In: Garrity GM, Brenner DJ, Kreig NR, Staley JR, editors. Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Volume 2: The Proteobacteria. New York: Springer; 2005. pp. 607–624. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hall BG. Chromosomal mutation for citrate utilization by Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 1982;151:269–273. doi: 10.1128/jb.151.1.269-273.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jeong H, et al. Genome sequences of Escherichia coli B strains REL606 and BL21(DE3) J. Mol. Biol. 2009;394:644–652. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.09.052. 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fogle CA, Nagle JL, Desai MM. Clonal interference, multiple mutations and adaptation in large asexual populations. Genetics. 2008;180:2163–2173. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.090019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Treves DS, Manning S, Adams J. Repeated evolution of an acetate-crossfeeding polymorphism in long-term populations of Escherichia coli. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1998;15:789–797. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rozen DE, Schneider D, Lenski RE. Long-term experimental evolution in Escherichia coli. XIII. Phylogenetic history of a balanced polymorphism. J. Mol. Evol. 2005;61:171–180. doi: 10.1007/s00239-004-0322-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glickman BW, Radman M. Escherichia coli mutator mutants deficient in methyl-instructed DNA mismatch correction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1980;77:1063–1067. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.2.1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sniegowski PD, Gerrish PJ, Lenski RE. Evolution of high mutation rates in experimental populations of E. coli. Nature. 1997;387:703–705. doi: 10.1038/42701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lara FJS, Stokes JL. Oxidation of citrate by Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1952;63:415–420. doi: 10.1128/jb.63.3.415-420.1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pos K, Dimroth P, Bott M. The Escherichia coli citrate carrier CitT: a member of a novel eubacterial transporter family related to the 2-oxoglutarate/malate translocator from spinach chloroplasts. J. Bacteriol. 1998;180:4160–4165. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.16.4160-4165.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhu L, Deutsher MP. The Escherichia coli rna gene encoding RNase I: sequence and unusual promoter structure. Gene. 1992;119:1–6. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90072-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shankar S, Schlictman D, Chakrabarty AM. Regulation of nucleoside diphosphate kinase and an alternative kinase in Escherichia coli: role of the sspA and rnk genes in nucleoside triphosphate formation. Mol. Microbiol. 1995;17:935–943. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17050935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Usakin LA, Kogan GL, Kalmykova AI, Gvozdev VA. An alien promoter capture as a primary step of the evolution of testes-expressed repeats in the Drosophila melanogaster genome. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2005;22:1555–1560. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adam D, Dimitrijevic N, Schartl M. Tumor suppression in Xiphophorus by an accidentally acquired promoter. Science. 1993;259:816–819. doi: 10.1126/science.8430335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bock R, Timmis JN. Reconstructing evolution: gene transfer from plastics to the nucleus. BioEssays. 2008;30:556–566. doi: 10.1002/bies.20761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Whoriskey SK, Nghiem V, Leong P, Masson J, Miller JH. Genetic rearrangements and gene amplification in Escherichia coli: DNA sequences at the junctures of amplified gene fusions. Genes Dev. 1987;1:227–237. doi: 10.1101/gad.1.3.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Janausch IG, Zientz E, Tran QH, Kroger A, Unden G. C4-dicarboxylate carriers and sensors in bacteria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1553:39–56. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(01)00233-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Andersson DI, Slechta ES, Roth JR. Evidence that gene amplification underlies adaptive mutability of the bacterial lac operon. Science. 1998;282:1133–1135. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reams D, Kofoid E, Savageau M, Roth JR. Duplication frequency in a population of Salmonella enterica rapidly approaches steady state with or without recombination. Genetics. 2010;184:1077–1094. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.111963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mpl8 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gunsalus RP, Park SJ. Aerobic-anaerobic gene regulation in Escherichia coli: control by the ArcAB and Fnr regulons. Res. Microbiol. 1994;145:437–450. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(94)90092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nizam SA, Zhu J, Ho PY, Shimizu K. Effects of arcA and arcB genes knockout on the metabolism in Escherichia coli under aerobic condition. Biochem. Eng. J. 2009;44:240–250. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Charlier D, Piette J, Glansdorff N. IS3 can function as a mobile promoter. Nucleic Acids Res. 1982;10:5935–5948. doi: 10.1093/nar/10.19.5935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lenski RE, Rose MR, Simpson SC, Tadler SC. Long-term experimental evolution in Escherichia coli. I. Adaptation and divergence during 2,000 generations. Am. Nat. 1991;138:1315–1341. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barrick JE, Knoester DB. breseq. 2010 http://barricklab.org/breseq. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Camin JH, Sokal RR. A method for deducing branching sequences in phylogeny. Evolution. 1965;19:311–326. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bjarnason J, Southward CM, Surette MG. Genomic profiling of iron-responsive genes in Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium by high-throughput screening of a random promoter library. J. Bacteriol. 2003;185:4973–4982. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.16.4973-4982.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zaslaver A, et al. A comprehensive library of fluorescent transcriptional reporters for Escherichia coli. Nature Methods. 2006;3:623–628. doi: 10.1038/nmeth895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Herring CD, Glasner JD, Blattner FR. Gene replacement without selection: regulated suppression of amber mutations in Escherichia coli. Gene. 2003;311:153–63. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(03)00585-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Christensen WB. Hydrogen sulfide production and citrate utilization in the differentiating of enteric pathogens and coliform bacteria. Res. Bull. Weld County Health Dept. Greeley Colo. 1949;1:3–16. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.