Abstract

Data from the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth (N=11,180) are used to examine the intergenerational transmission of nonmarital childbearing for U.S. men and women. Findings suggest that being born to unmarried parents increases the risk of offspring having a nonmarital first birth, net of various confounding characteristics. This intergenerational link appears to particularly operate via parents’ breaking up before offspring are age 14 and offspring’s young age at first sex. While the link across two generations in nonmarital childbearing is not accounted for by parents’ socioeconomic status (measured as fathers’ education), several mediating factors vary by socioeconomic background. Gender and race/ethnicity also moderate the intergenerational transmission of nonmarital childbearing. This research sheds light on the prevalence of, and process by which, nonmarital childbearing is repeated across generations, which has important implications for long-term social stratification and inequality.

Keywords: Intergenerational transmission, National Survey of Family Growth, nonmarital childbearing

1. Introduction

At the intersection of changes in union formation and childbearing behaviors since the middle of the 20th century is a notable increase in nonmarital childbearing in the U.S. (and many Western countries): Nonmarital childbearing in the U.S. has risen steadily from 6% of all births in 1960 to fully 41% of all births in 2009, with much higher proportions among racial and ethnic minorities (Martin et al., 2011). Much of this increase is associated with births born to couples in cohabiting unions (Bumpass & Raley, 1995; Raley, 2001). However, unlike their European counterparts, we know that unmarried parents in the U.S., even those in cohabiting unions, tend to be economically disadvantaged (with a high school education or less), experience high levels of union instability, and often have complex family situations due to high rates of paternal incarceration and multi-partnered fertility (McLanahan, 2011; Osborne & McLanahan, 2007). These circumstances may diminish the well being of children born to unmarried parents—extending into adulthood—and may have implications for growing societal inequality within and across generations.

Despite a host of related studies, to our knowledge, whether nonmarital childbearing is transmitted across generations has not been directly examined in the extant research, although the intergenerational transmission of other family-related behaviors has been well-documented. For example, U.S. children whose parents divorced during their childhood are themselves more likely to dissolve their marriages as adults (P. R. Amato, 1996; L. L. Bumpass, Martin, & Sweet, 1991; Li & Wu, 2008; McLanahan & Bumpass, 1988; Wolfinger, 2000), and this holds true in European countries as well (Diekmann & Schmidheiny, 2008). Research has also shown that early childbearing is transmitted across generations for both men and women: offspring whose fathers and mothers have an early first birth are significantly more likely to have an early first birth themselves (Barber, 2001; Pears, Pierce, Kim, Capaldi, & Owen, 2005; Thornberry, Smith, & Howard, 1997). While most early (teenage) births are nonmarital, it is no longer the case that most nonmarital births occur to teenagers; in fact, only 21 percent of unmarried births in 2009 occurred to teenagers (Martin et al., 2011). Therefore, we focus on the broader phenomenon of nonmarital childbearing across generations regardless of age.

Compared to the large body of research examining the link between family structure and women’s childbearing and family formation behaviors (Albrecht & Teachman, 2003; Driscoll et al., 1999; Hogan & Kitagawa, 1985; McLanahan & Bumpass, 1988; McLanahan & Sandefur, 1994; Powers, 1993; Wu, 1996; Wu & Martinson, 1993), we know significantly less about men. While our focus is on nonmarital childbearing rather than single parenthood (although the risk of spending time in a single-parent home is greater for those who are born to unmarried parents), several studies have focused on the influence of having a single parent on men’s childbearing behaviors. Men whose fathers were absent from the home during childhood and those who experienced multiple family transitions are significantly more likely to transition into parenthood early (Forste & Jarvis, 2007; Furstenberg & Weiss, 2000), although the former appears to be less true for more recent cohorts (Goldscheider, Hofferth, Spearin, & Curtin, 2009). Men raised by one parent are also more likely to have a child outside of marriage (Carlson, VanOrman, & Pilkauskas, 2010), to have children with more than one partner (Carlson & Furstenberg, 2006; Guzzo & Furstenberg, 2007), and to live apart from their child(ren) (Guzzo and Furstenberg, 2007). Although early childbearing is not our primary focus here, early childbearing has been shown to be transmitted across generations—from mothers to sons (Pears et al., 2005; Sipsma, Biello, Cole-Lewis, & Kershaw, 2010; Thornberry et al., 1997). Given the relative dearth of studies examining nonmarital childbearing for men—particularly beyond teen/early fatherhood—we extend the literature to examine how nonmarital childbearing is reproduced across generations for not only women, but also for men between ages 15 and 44.

In this paper, the following three research questions are examined: First, is nonmarital childbearing transmitted across generations, net of several background selection factors? Second, does any intergenerational association appear to operate via family of origin and/or respondents’ characteristics? Third, do gender, race/ethnicity, or parental education moderate the association between parents’ and offspring’s nonmarital childbearing? To address these questions, we use Cox proportional hazard models with data from the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth to estimate offspring’s (both men’s and women’s) risk of having a nonmarital birth between the ages of 15 and 44, controlling for a number of covariates. This research sheds light on how major changes in family demography over the last half century may have long-run consequences for subsequent generations.

2. Conceptual Framework and Empirical Research

2.1 The context of nonmarital childbearing in the United States

Over the last half century, nonmarital childbearing has increased dramatically in the United States, and the complexity of family forms has grown tremendously, particularly among low-income families. Cohabitation prior to, and in some cases replacing, marriage is also more common than in recent decades (for a comprehensive review, see Smock, 2000). While many Western countries have witnessed an increase in cohabitation (and nonmarital childbearing), cohabiting unions into which children are born tend to be more fragile in the U.S. compared to other Western countries. A higher percentage of cohabiting unions end within five years in the United States (55%) compared to Great Britain (36%), France (29%), Canada (32%), Sweden (37%) and others (Cherlin, 2009). A recent study further shows that parents who cohabit in the U.S. are more likely to be disadvantaged and to have less stable relationships compared to parents who cohabit in Great Britain (Kiernan et al., 2011).

In and of itself, being born to unmarried parents may not be consequential for children; however, the family instability that often follows nonmarital childbearing likely has negative consequences for children. Graefe and Litcher (1999) argue that children born into cohabitation (or whose parents subsequently cohabit) will likely experience quick subsequent family transitions. Numerous studies from the Fragile Families and Child Well being Study further show that unmarried parents, including those who cohabit, are more likely than married parents to experience numerous partnership transitions (e.g., Beck, Cooper, McLanahan, & Brooks-Gunn, 2010; McLanahan, 2011); these transitions have been shown to negatively affect children’s cognitive, behavioral, and physical outcomes, with some differences across race/ethnic groups (Fomby and Cherlin, 2007; Cooper et al., 2011; Bzostek and Beck, 2011). Given that unmarried cohabiting parents tend to be socioeconomically disadvantaged, the family instability associated with nonmarital childbearing conceivably exacerbates these already precarious child rearing contexts. The focus here is on nonmarital childbearing across two generations due to its likely negative consequences for offspring as children and as they transition to adulthood.

2.2 The intergenerational transmission of nonmarital childbearing

The life course perspective draws our attention to the “linked lives” of individuals within the social world and the fact that the experiences of one generation affect the experiences of older and younger generations (Bengtson & Allen, 1993; Elder, 1994, 1998). In particular, the timing and context in which adults make the transition to parenthood affects the experiences of the children they will then raise. There are a number of ways that nonmarital childbearing by parents might be linked to nonmarital childbearing by their offspring.

Socioeconomic Disadvantage (Selection)

First, as noted above, we know that having a child outside of marriage is not a random event: parents who have children outside of marriage are typically disadvantaged with respect to education, earnings, and income (Beck, Cooper, McLanahan, & Brooks-Gunn, 2010; Nock, 1998). Parents’ education and economic resources are central to children’s development and life chances, as they enable parents to purchase the necessary material goods and services (such as medical care, higher quality child care and schools, as well as books, toys and experiences) that enhance well-being. It is well-known that socioeconomically disadvantaged parents experience more hardship and face greater challenges in rearing their children, which in turn affects children’s outcomes, even as they become adults (Berger, Paxson, & Waldfogel, 2009; Duncan & Brooks-Gunn, 1997).

Children born to low-income parents are more likely to be low-income themselves in later life (Gottschalk, 1992). With respect to our research question, grown children of disadvantaged parents may be more likely to experience a nonmarital first birth because they are more likely to leave the parental home earlier and thus begin family formation earlier (Aassve, 2003). Therefore, a key reason that nonmarital childbearing of parents and their offspring may be linked is due to the prior socioeconomic disadvantage of parents who had a child outside of marriage, i.e. social selection—or, that low parental socioeconomic status predicts nonmarital childbearing of both the parents and their offspring.

Family of Origin Characteristics

To the extent that nonmarital childbearing has a causal effect on offspring nonmarital childbearing, there may be several important mechanisms—the first having to do with aspects of the offspring’s family of origin. Parents play an important role in shaping the next generation (Baumrind, 1966, 1986) via the modeling of family norms, roles, and relationships observed during childhood and beyond (Barber, 2001; Bengtson, 1975). For example, we know that those who experience their parents’ divorce will be more likely to later divorce themselves (McLanahan & Bumpass, 1988) in part because they are socialized to have a lower commitment to the institution of marriage (Amato and DeBoer, 2001). Those reared by unmarried parents—particularly those who do not have lasting relationships—may also develop normative attitudes and beliefs that may subsequently contribute to their likelihood of having a nonmarital first birth.

As noted above, at least for contemporary unmarried parents, the majority of couples who have a child together are likely to break up within only a few years of a child’s birth (Högnäs & Carlson, 2011), and many will experience multiple new partnerships (Beck et al., 2010). Again, while many nonmarital births today occur within cohabiting unions, these unions tend to be less stable than marital unions (Graefe and Litcher 1999; Beck et al., 2010; McLanahan, 2011). Although two-parent families are not always better for children (Furstenberg & Kiernan, 2001; Musick & Meier, 2010), on average, single-parent families are less able to provide the quantity and quality of parenting that two-parent families can provide, including the level of monitoring (Amato, 1987; Sigle-Rushton & McLanahan, 2004; Thomson, Hanson, & McLanahan, 1994); a single parent may find it more difficult than two parents to identify, address, and thwart ‘risky’ behaviors such as early age at first sexual intercourse (Wu & Thomson, 2001), which is linked to nonmarital childbearing.

Unmarried mothers—at least those who become single mothers—may have greater impetus to work (or work more hours) as the primary breadwinner in their household. Children of employed mothers receive less supervision than those of mothers who are not employed, particularly during after-school hours (Muller, 1995). Although mother’s employment has been shown to have little effect on children’s cognitive and behavioral outcomes in Britain (Verropoulou & Joshi 2009), some evidence from the U.S. suggests that maternal employment is associated with higher levels of negative youth behaviors such as smoking, drinking, and sexual activity (Ruhm, 2008).

Also, since parental resources are finite, having a greater number of siblings is associated with fewer resources for any particular child, and children born to unmarried parents typically have a greater number of siblings than those born to married parents (Barber, 2001). The resource dilution hypothesis suggests that as the number of siblings increase, parental investments in any given child (in terms of economic resources, energy, and time) decrease, resulting in poorer child outcomes (Blake, 1981, 1989). Children reared in large versus small families achieve less education and perform less well in school (Blake, 1989; Downey, 1995). Parents have fewer economic resources to invest in children’s education as a result of having fewer resources at the outset (lower socioeconomic groups have larger families) and dividing resources between children. In addition, parents, especially working single parents, also have less time and energy to monitor and control their children’s risky behaviors in larger families (Barber, 2001). In sum, because children who are born to unmarried parents are at a greater risk of experiencing their parents’ union dissolution (and multiple partnership transitions) and associated parental time constraints compared to children of married parents, we expect that children born to unmarried parents are also at a greater risk of having a nonmarital first birth.

Offspring socioeconomic status

A second key mechanism by which nonmarital childbearing may be repeated across generations is via offspring socioeconomic status, proxied by educational attainment. Nonmarital childbearing—and the single parenthood and/or family instability that often results—negatively affects educational attainment among children (Krein & Beller, 1988), while greater educational attainment (and the economic resources with which it is correlated) increases the opportunity cost of—and hence discourages—childbearing (Becker, 1991; Willis, 1999). At the same time, higher economic resources increase one’s ability to afford having a child outside of marriage, the so-called ‘independence effect’ (Oppenheimer, 1988) or ‘self-reliance effect’ (Aassve, Burgess, Chesher, & Propper, 2002). However, the empirical evidence supports the opportunity-cost argument and suggests that women’s earnings capacity is negatively associated with premarital childbearing, though the magnitude is modest (Aassve, 2003); for men, higher levels of completed education and remaining enrolled in school are shown to decrease the risk of teen unwed childbearing (Lerman, 1993; Marsiglio, 1987). Therefore, we would expect offspring with higher levels of educational attainment to have a lower risk of nonmarital childbearing.

2.3 Moderating Factors

Variation by gender

Since women physically experience pregnancy and childbirth and typically have greater responsibility for child care, we might expect the intergenerational transmission of nonmarital childbearing to be stronger for women than men. In other words, women may be more sensitive to the role modeling that occurs vis-à-vis a particular context in which birth and childrearing occur. Moreover, prior research shows that men and women experience early childbearing as a result of different family of origin characteristics (Hofferth and Goldscheider, 2010); therefore, we examine here whether gender moderates the intergenerational association between parents’ and children’s nonmarital childbearing. Examining the childbearing patterns of men is not, however, without limitations. Prior research has shown that men tend to underreport the number of children they have—either because they do not know about these births, they fail to remember them, or for other reasons—particularly early nonmarital births. Still, if we are to understand the pathways through which nonmarital childbearing is transmitted from one generation to the next, we must consider differences in how men and women become unmarried parents.

Variation by race/ethnicity

The fraction of births that occur outside of marriage has long been higher among racial and ethnic minorities. As of 2009, fully 73% of non-Hispanic African American births and 53% of Hispanic births occurred outside of marriage, compared to 29% of non-Hispanic White births (Martin et al., 2011). The higher prevalence among African Americans has been attributed to neighborhood differences in concentrations of poverty (South & Baumer, 2000; Wilson, 1987), and some have argued that early sexual intercourse, less consistent contraception, and childbearing outside of marriage are more normative in African American communities (Furstenberg, 1987). Whether concentrated neighborhood poverty and/or norms explain the higher prevalence of nonmarital childbearing, these circumstances suggest that within African American families, parents’ nonmarital childbearing might be less predictive of men’s and women’s nonmarital childbearing as compared to other race/ethnic groups in which it is less common.

Variation by parental education

Similarly, as noted above, nonmarital childbearing is more common among individuals of low socioeconomic status (Aassve, 2003; Hoffman & Foster, 1997; Trent, 1994). Therefore, we might expect that being born outside of marriage is even more strongly linked to offspring nonmarital childbearing in the context of low parental education (our measure of SES). Greater socioeconomic resources may buffer the negative intergenerational effects of being born to unmarried parents, as offspring delay childbearing in order to pursue career and/or other opportunities. That is, children born outside of marriage to parents with relatively greater economic resources may be less likely to repeat the pattern of themselves having a nonmarital birth than their counterparts born to less advantaged parents.

3. Method

3.1 Data

Data from the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) are used to examine the link between respondents having been born outside of marriage and their own subsequent risk having a nonmarital first birth. The NSFG was historically a study of women ages 15–44 with six repeated cross-sections interviewed between 1973 and 2002; the surveys include detailed questions about women’s sexual activity, contraception, pregnancy and birth, and partnerships. In Cycle 6 in 2002, in-person interviews were conducted with 7,643 women ages 15–44, with a response rate of 80%. Fifty-eight percent (n=4,413) of these women reported having at least one biological child, 45% (n=1,971) of which were born outside of marriage (i.e., first births and subsequent births).

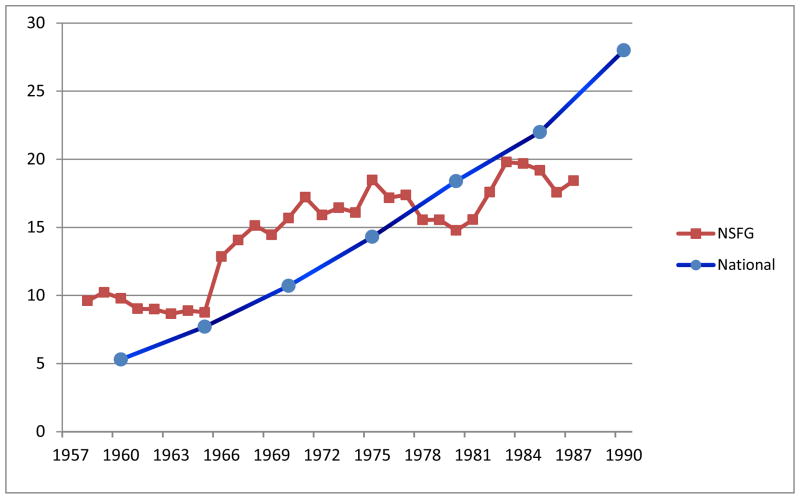

For the first time in 2002, the NSFG included in-person interviews with 4,928 men ages 15–44, with a response rate of 78%. Thirty-five percent (n=1,731) of these men reported having at least one biological child, 47% (n=808) of which were born outside of marriage (i.e., first births and subsequent births). Even though these data are cross-sectional, they can be used to construct retrospective longitudinal histories, so we can examine the link between marital statuses at birth across two generations (parents and their adult children). As noted above, previous research has documented that men tend to underreport births in surveys (Joyner et. al, 2012; Rendall et. al., 1999), although comparisons drawn between the NSFG and vital statistics data suggest only minor under-reporting in later cohorts (Martinez et. al., 2006). We plotted the birth status of men in the NSFG (i.e., whether their parents were married at the respondent’s birth) as compared with national figures reported by the National Center for Health Statistics (see Figure 1) over years 1960 to 1987 (the year the youngest [age 15] NSFG respondents were born); this comparison suggests that the NSFG data follow the same trend line as the national data, although nonmarital births before 1978 may have been slightly over-reported and after 1978 slightly under-reported, compared to the national figures.

Figure 1.

Percent of Sons’ Parents’ NMBs Reported in the NSFG (1957–1988) and Percent of Total NMBs, National Center for Health Statistics (1960–1990)

Note : NMB: nonmarital birth.

Missing data on our independent and dependent variables and our covariates are always less than 10%. Given the small percentage missing on any given variable, we do not suspect that missing values introduce substantial bias in our results. After accounting for combined missing in each sample we have an analytic sample size of N=11,180 (4,416 men and 6,764 women).

3.2 Independent and Dependent Variables

In the 2002 cycle of the NSFG, both men and women were asked about their marital status at the time their first child was born (and the date that this occurred). The dependent variable is the risk of having a nonmarital first birth versus not having a nonmarital first birth, or the rate of offspring’s nonmarital first births. Those who were married are censored at the date of marriage, and those who never reported a birth are censored at the time of the survey.1 In other words, ‘failure’ in our event history framework is having a nonmarital first birth, and all others are censored at marriage or at the survey date.

The main independent variable of interest is whether or not respondents’ parents were married at the time of their birth. In Cycle 6 of the NSFG, both men and women were asked “Were your biological parents married to each other at the time of your birth?” which we use to measure parents’ having a nonmarital birth. Those whose parents were not married at their birth are coded as a 1, and respondents whose parents were married at their birth are coded as a 0 (reference category).

3.3 Covariates

Control variables were selected based on prior research, particularly literature related to factors associated with childbearing behaviors for women, given the more extensive body of research about women (e.g., Barber, 2001; McLanahan and Sandefur, 1994; Wu and Thompson, 2001). Four dummy variables for respondents’ race/ethnicity are used: non-Hispanic White (reference), Hispanic, non-Hispanic African American, and non-Hispanic Other. To account for the secular change in nonmarital childbearing, respondents’ birth cohort is included, using three dummy variables for ten-year birth cohorts of those born just before or during the 1960s (reference), 1970s, and 1980s. A dummy variable to indicate whether respondents’ mothers were younger than age 20 when their first child was born is also included.

To measure socioeconomic background, we use parents’ educational attainment, which is strongly related to parental earnings and household income (the latter are not available in the NSFG); fathers’ education is measured using four dummy variables: less than high school (reference), high school degree, some college, and a college degree or more. A dummy variable indicating whether the mother had more education than the father is included for parsimony (and because mothers’ and fathers’ education tend to be highly correlated). Family of origin characteristics are represented by three variables: a dummy variable indicating whether or not respondents’ parents had broken up by the time they were age 14, a dummy variable indicating whether the mother worked during the respondents’ childhood, and a continuous measure of respondents’ number of siblings. A dummy variable is used to indicate whether the respondent initiated sexual activity by age 15. Religion in which the respondent was raised is measured using five dummy variables: no religion (reference), Catholic, conservative Protestant, Protestant, and Other. Level of education of the respondent is measured with four dummy variables: less than a high school degree (reference), high school degree, some college, and a college degree or more.

3.4 Analytic Approach

The goal is to estimate how parents’ marital status at offspring’s birth influences their subsequent risk of having a nonmarital first birth, net of covariates. Consistent with prior research on childbearing behaviors (Bumpass & McLanahan, 1989; Guzzo & Hayford, 2009; Wu & Thomson, 2001), we estimate Cox proportional hazard regression models. These event-history models do not require that researchers make assumptions about the timing of nonmarital births (Allison, 1995). Although intuitively, the expectation is that such births occur more frequently in the early twenties and less frequently in the mid- to late thirties and early forties, this commonly-used approach allows nonmarital births to occur at any point during the risk period—in this case is between ages 15 and 44.

Within the hazard model, the numerator is the number of nonmarital first births, and the denominator is the number of person-months that respondents are exposed to the risk of having a nonmarital birth. Cases are censored at marriage (or at the survey if no birth occurred) because we are interested in individuals bearing children before ever marrying.2 The risk period begins at age 15. Therefore, for our time measure we subtract the date at which the respondents were 15 years old from their first child’s date of birth. We also ran models (not shown) starting the risk period at age at first sex, and the substantive results were very similar. Given the potential for recall problems of age at first sex, particularly for older cohorts who initiated sex long prior to the interview, and because we want to retain those who had not yet had sex in our sample, we set the risk period starting at age 15 for our main analyses.

Six models using a pooled sample consisting of both men and women are estimated. Model 1 includes background controls for race/ethnicity, birth cohort, and whether the respondent’s mother had her first birth before age 20. Model 2 adds socioeconomic background, measured by fathers’ educational attainment and whether the mothers’ education was greater than the fathers’; this model allows us to evaluate the extent to which the link between parent and offspring nonmarital childbearing is due to selection on parental socioeconomic disadvantage. Model 3 adds three measures of family of origin characteristics—whether the respondent’s parents broke up by age 14, whether the mother worked during the respondent’s childhood, and respondents’ number of siblings; we can evaluate whether nonmarital childbearing appears to affect offspring via these factors. Model 4 adds respondents’ characteristics—whether respondents had sex by age 15, religion in which respondent was raised, and level of educational attainment. In order to determine whether nonmarital childbearing differs by offspring’s cohort, Model 5 adds an interaction between respondents’ birth cohort and whether or not their parents were married at the time of their birth. Finally, given that the timing of first births differed between men and women in the NSFG (66% of women had their first birth at age 20 or older compared to 82% of men), and the potential for parents’ nonmarital childbearing to influence men’s and women’s subsequent childbearing behaviors differently, in Model 6 we add an interaction between respondents’ gender and whether or not their parents were married at the time of their birth.

4. Results

4.1 Descriptive Statistics

We begin by describing the characteristics of the sample. Table 1 shows the weighted means and percentages for our covariates; figures are shown separately for men and women by their parents’ marital status at the time of their birth. Beginning with background characteristics, men whose parents were married when they were born are much more likely to be White (70%) than either African American (9%) or Hispanic (15%), while men born to unmarried parents are more evenly divided by race/ethnicity (38% are White, 33% are African American, and 25% are Hispanic). The difference in race/ethnicity by parents’ marital status is in the same direction but larger for women. A higher percentage of men and women whose parents were unmarried at the time of their birth were born in later cohorts compared to earlier cohorts, consistent with the overall rise in nonmarital childbearing in recent decades. Men and women born to unmarried parents are much more likely to have mothers who were teenagers at their first birth. Parents who were not married at the time of respondents’ birth were less likely to have completed college than parents who were married at the time of their birth.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics For Men and Women by Their Parents’ Marital Status at Their Birth

| Men

|

Women

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parents Married | Parents Not Married | Parents Married | Parents Not Married | |

|

|

|

|||

| M or % (sd) | M or % (sd) | |||

| Background Characteristics | ||||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 69.8 | 38.0 | 71.3 | 32.2 |

| African American | 8.8 | 32.7 | 9.2 | 41.8 |

| Hispanic | 15.4 | 24.8 | 13.7 | 22.2 |

| Other | 6.0 | 4.5 | 5.8 | 3.7 |

| Respondent’s Birth Cohort | ||||

| Cohort 1960s | 31.1 | 21.3 | 34.7 | 23.0 |

| Cohort 1970s | 28.9 | 31.1 | 34.8 | 34.9 |

| Cohort 1980s | 40.0 | 47.6 | 30.5 | 42.1 |

| Mother’s age at first birth < 20 | 27.9 | 55.3 | 31.5 | 54.9 |

| Socioeconomic Background | ||||

| Father’s Education | ||||

| Less than High School | 22.9 | 35.0 | 22.8 | 32.5 |

| High School Degree | 30.2 | 35.6 | 30.8 | 36.9 |

| Some College | 19.5 | 14.4 | 19.1 | 18.1 |

| College Degree or More | 27.3 | 15.0 | 27.3 | 12.6 |

| Mother has higher educ than father | 21.5 | 24.8 | 21.5 | 25.3 |

| Family of Origin Characteristics | ||||

| Parents Broke Up by Age 14 | 18.8 | 51.4 | 19.6 | 55.7 |

| Mother worked during childhood | 66.9 | 74.5 | 68.4 | 73.8 |

| Number of siblings | 3.37 (1.52) | 3.48 (1.71) | 3.45 (1.56) | 3.47 (1.81) |

| Respondent Characteristics | ||||

| Age at First Sex ≤ 15 Years Old | 0.6 | 1.3 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| Religion Raised | ||||

| No Religion | 7.8 | 8.9 | 7.0 | 10.7 |

| Catholic | 36.1 | 33.0 | 36.3 | 30.8 |

| Conservative Protestant | 22.6 | 32.8 | 22.6 | 37.7 |

| Protestant | 26.2 | 21.1 | 28.2 | 17.9 |

| Other | 7.3 | 4.1 | 5.9 | 3.0 |

| Education | ||||

| Less than High School | 20.9 | 35.2 | 17.7 | 37.1 |

| High School Degree | 30.7 | 36.8 | 27.2 | 31.3 |

| Some College | 27.1 | 22.0 | 30.2 | 22.8 |

| College Degree or More | 21.4 | 6.1 | 24.9 | 8.9 |

| N | 3,733 | 683 | 5,853 | 911 |

Note : All figures are weighted by sampling weights. Ns are unweighted.

With respect to family of origin characteristics, for both men and women, more than 50% of those whose parents were not married at their birth broke up by the time they were age 14 compared to less than 20% of those whose parents were married at the time of their birth. Not surprisingly, men and women born to unmarried parents are slightly more likely to have mothers who worked during their childhood compared to those whose parents were married at the time of their birth. There are no differences between those whose parents were married or unmarried at the time of their birth with respect to their average number of siblings, which is relatively high for all groups (around 3.4–3.5).

In terms of respondent characteristics, few men or women had sex at age 15 or younger (less than 2% of all groups). There are few differences in the religion in which respondents were raised by whether or not their parents were married at their birth. Educational attainment is much lower for those born outside of marriage: 35% and 37%, respectively, of the men and women of unmarried parents have less than a high school degree, compared to 21% of men and 18% of women whose parents were married at their birth. Moreover, a higher percentage of both men and women of married parents have at least some college and are much more likely to have a college degree.

Given the focus on the intergenerational transmission of nonmarital childbearing, next we describe men’s and women’s childbearing status by parents’ marital status at their birth (Table 2). Findings indicate that a larger proportion of men and women had a nonmarital first birth if their parents were unmarried at the time of their own birth: 26% of men born to unmarried parents subsequently had a nonmarital first birth compared to 15% of those whose parents were married at their birth. The difference is even greater for women, with 39% of women born to unmarried parents having a nonmarital first birth compared to 18% of women whose parents were married at their own birth. The majority of men, and just under half of the women in the sample, had no birth by the date of the survey. Based on chi-square tests (not shown), these differences by parents’ marital status at birth are all statistically significant.

Table 2.

Men’s and Women’s Childbearing Status at Time of Survey by Their Parents’ Marital Status at Their Birth

| Parents’ Marital Status at Respondent’s Birth (%)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| All | Married | Unmarried | |

|

| |||

| Men | |||

| Nonmarital first birth | 16 | 15 | 26 |

| Marital first birth | 30 | 31 | 15 |

| No birth | 54 | 54 | 59 |

| Total % | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| N | 4,416 | 3,733 | 683 |

| Women | |||

| Nonmarital first birth | 20 | 18 | 39 |

| Marital first birth | 38 | 40 | 20 |

| No birth | 42 | 42 | 41 |

| Total % | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| N | 6,764 | 5,853 | 911 |

Note : All figures are weighted by sampling weights. Ns are unweighted.

4.2 Cox Proportional Hazard Analyses

Turning now to the multivariate analyses, Table 3 shows results from the Cox proportional hazards models predicting the risk of a nonmarital first birth as a function of parents’ marital status at birth and other covariates from our pooled sample of men and women. We report hazard ratios, which indicate the risk of having a nonmarital first birth (versus having a marital first birth or no birth) by the date of the interview. Hazard ratios greater than one indicate an increased risk—and hazard ratios less than one indicate a decreased risk—of having a nonmarital first birth during the risk period as a function of a given variable.

Table 3.

Results from Cox Proportional Hazard Models Predicting the Risk of Offspring’s Nonmarital First Birth by Parents’ Marital Status at their Birth (N =11,180)a

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parents’ Nonmarital Birth | 1.48 *** | 1.43 *** | 1.24 *** | 1.16 ** | --- | --- |

| Race/Ethnicity (ref=White) | ||||||

| Hispanic | .41 *** | .49 *** | .51 *** | .59 *** | .59 *** | .57 *** |

| African American | 3.37 *** | 3.13 *** | 2.92 *** | 2.64 *** | 2.64 *** | 2.66 *** |

| Other | 1.11 | 1.16 | 1.14 | 1.30 * | 1.29 * | 1.33 * |

| Respondent’s Birth Cohort (ref=Cohort 1960s) | ||||||

| Cohort 1970s | 1.44 *** | 1.52 *** | 1.55 *** | 1.54 *** | --- | 1.52 *** |

| Cohort 1980s | 1.62 *** | 1.76 *** | 1.80 *** | 1.49 *** | --- | 1.54 *** |

| Mother age at first birth < 20 | 1.72 *** | 1.52 *** | 1.41 *** | 1.30 *** | 1.30*** | 1.28 *** |

| Socioeconmic Background | ||||||

| Father’s Education (ref=Less than HS) | ||||||

| High School Degree | .94 | .94 | 1.11 † | 1.10 † | 1.11 † | |

| Some College | .71 *** | .72 *** | 1.02 | 1.02 | 1.01 | |

| College Degree or More | .42 *** | .43 *** | .75 ** | .75 ** | .76 ** | |

| Mother has higher educ than father | .82 *** | .82 *** | .96 | .96 | .97 | |

| Family of Origin Characteristics | ||||||

| Parents Broke Up by Age 14 | 1.59 *** | 1.50 *** | 1.50 *** | 1.49 *** | ||

| Mother worked during childhood | 1.12 * | 1.12 * | 1.12 * | 1.14 ** | ||

| Number of siblings | 1.08 *** | 1.05 ** | 1.05 ** | 1.04 ** | ||

| Respondent Characteristics | ||||||

| Age at First Sex ≤ 15 Years Old | 1.74 * | 1.76 * | 2.05 *** | |||

| Catholic | 1.14 | 1.13 | 1.13 | |||

| Conservative Protestant | 1.18 † | 1.17 † | 1.18 † | |||

| Protestant | .98 | .99 | .97 | |||

| Other | .72 * | .72 * | .77 † | |||

| Education (ref=Less than HS) | ||||||

| High School Degree | .70 *** | .70 *** | .68 *** | |||

| Some College | .44 *** | .44 *** | .41 *** | |||

| College Degree or More | .17 *** | .17 *** | .15 *** | |||

| Birth Cohort Interaction (ref=NMB & Cohort 1960s) | ||||||

| Parents’ NMB & Cohort 1970s | 1.27 * | --- | ||||

| Parents’ NMB & Cohort 1980s | 1.42 ** | --- | ||||

| Parents’ MB & Cohort 1960s | .76 ** | --- | ||||

| Parents’ MB & Cohort 1970s | 1.23 * | --- | ||||

| Parents’ MB & Cohort 1980s | 1.13 | --- | ||||

| Gender Interaction (ref=NMB & Female) | ||||||

| Parents’ NMB & Male | .44 *** | |||||

| Parents’ MB & Male | .46 *** | |||||

| Parents’ MB & Female | .85 ** | |||||

p<.10

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

Note: NMB: Nonmarital birth. MB: Marital birth

Hazard ratios are reported in each model.

Focusing on Model 1, respondents are at a significantly higher risk of having a nonmarital first birth (than a marital or no birth) if their parents were not married at their birth, when we control for race/ethnicity, cohort, and mothers’ age at first birth. Once socioeconomic background is added in Model 2, the hazard ratio for respondents’ risk of having a nonmarital first birth if their parents had a nonmarital birth decreases only slightly (from 1.48 to 1.43), suggesting that socioeconomic background plays a very limited role in men’s and women’s risk. In other words, in answer to our first research question, parents’ nonmarital childbearing is associated with offspring’s nonmarital childbearing net of selection on parental socioeconomic background (measured as parents’ education).

Adding family of origin characteristics in Model 3 reduces the magnitude of the nonmarital birth hazard ratio (from 1.43 to 1.24), suggesting that family background characteristics (particularly parents’ breaking up by age 14) partially account for how parents’ nonmarital birth is linked to offspring’s nonmarital childbearing. All three family factors—having parents that broke up by child’s age 14, having a working mother, and having a higher number of siblings—are significantly associated with offspring’s greater likelihood of having a nonmarital first birth.

When respondent characteristics (Model 4) are included, the magnitude and significance of the estimate decreases again (1.24 to 1.16), suggesting that nonmarital childbearing also operates across generations via the timing of first sex and educational attainment of offspring (respondents’ religion growing up is not significantly associated with having a nonmarital first birth). As expected, respondents who had sex at age 15 or younger are at a significantly higher risk of having a nonmarital first birth. Also consistent with what we expected, each higher level of education is associated with a lower likelihood of nonmarital childbearing (compared to less than high school education). Thus, the answer to our second research question is that the intergenerational association does appear to partially operate via family background and respondent characteristics. At the same time, net of the confounding and mediating factors, adult offspring remain at a significantly increased risk of having a nonmarital first birth (versus a marital or no birth) if their parents were unmarried at their birth.

Model 5 includes the interaction for cohort by nonmarital birth, and we find some evidence that the association between parents’ and offsprings’ nonmarital childbearing is stronger among more recent cohorts. In particular, those born to unmarried parents in the 1970s and 1980s have an even greater risk of having a nonmarital birth compared to those born in the 1960s. Those born to married parents in the 1960s are at a significantly lower risk of having a nonmarital birth compared to those born to unmarried parents in the same cohort. Among more recent cohorts, however, parental marriage seems to be less protective against offspring’s nonmarital childbearing than in earlier cohorts.

Next, because parents’ marital status at offspring’s birth may affect male and female childbearing behavior differently, Model 6 includes an interaction between parents’ marital status at birth and offspring’s gender. The results suggest that regardless of parents’ marital status at offspring’s birth, men have a lower risk of having a nonmarital first birth (versus a marital birth or no birth) than women: compared to women whose parents were unmarried at their birth, men whose parents were either married or unmarried at their birth are at a significantly lower risk of having a nonmarital first birth, with hazard ratios of .46 and .44, respectively. The latter estimates are not significantly different from each other (results not shown), suggesting that men’s risk of having a nonmarital first birth does not, in fact, vary as a function of their parents’ marital status at their birth. By contrast, for women, those born to married parents are significantly less likely to have a nonmarital first birth (.85) than those born to unmarried parents. Thus, overall, these results indicate that women are more likely to have a nonmarital first birth, and there appears to be stronger intergenerational transmission of nonmarital childbearing for women than for men.

With respect to the covariates, focusing on Model 4 (the full model before the inclusion of the cohort and gender interactions), African Americans have a much greater risk (and Hispanics have a much lower risk) of having a nonmarital first birth compared to Whites. Offspring’s mothers’ having a teen first birth significantly increases their risk of having a nonmarital birth. Fathers’ having a college degree or more (versus less than a high school degree) significantly reduces offspring’s risk of having a nonmarital first birth. Parents’ breaking up by age 14, mother working during childhood, and number of siblings all significantly increase offspring’s risk of a having a nonmarital first birth. With respect to respondents’ characteristics, those who had first sex at age 15 or younger, compared to those who had sex at a later age, are at a significantly increased risk of having a nonmarital first birth. The religion in which offspring were raised has no significant association with their risk of having a nonmarital first birth, but respondents with a high school degree or more, and especially those with a college degree, are at a significantly lower risk of having a nonmarital first birth compared to those who have less than a high school degree.

Table 4 reports the results for the analysis of moderators, providing an answer to our third research question—whether the intergenerational transmission of nonmarital childbearing (or the mechanisms by which it operates) is moderated by respondents’ gender, race/ethnicity, and/or parents’ education. Each set of interactions is estimated in a separate model using the pooled sample of men and women and includes all covariates. Beginning with race/ethnicity, the results suggest that regardless of parents’ marital status at their birth, African Americans are at a much greater risk of having a nonmarital birth compared to Whites whose parents were unmarried at their birth. Hispanics whose parents were unmarried at their birth are also more likely to have a nonmarital birth than Whites with unmarried parents, but the hazard ratio for Hispanics with married parents is not statistically significant. Whites whose parents were married at their birth are less likely to have a nonmarital birth than those with unmarried parents; however, this hazard ratio is only marginally significant.

Table 4.

Hazard Ratios for Interactions by Parents’ Marital Status at Offsrping’s Birth and Father’s Education and Race, and by Fathers’ Education, Offspring’s Gender, and Select Covariates (N =11,180)a

| Race/Ethnicity Interaction (ref=NMB & White) | |

| Parents’ NMB & African American | 2.19 *** |

| Parents’ NMB & Hispanic | 1.87 *** |

| Parents’ NMB & Other | .96 |

| Parents’ MB & White | .79† |

| Parents’ MB & African American | 2.25 *** |

| Parents’ MB & Hispanic | 1.24 |

| Parents’ MB & Other | 1.05 |

| Interactions with Fathers’ (and Mothers’) Education | |

| Fathers’ Education Interactionb (ref=NMB & Low education) | |

| Parents’ NMB & High education | .81 * |

| Parents’ MB & High education | .73 *** |

| Parents’ MB & Low education | .86 * |

| Parents Broke Up by Age 14 & Fathers’ Education (ref=Parents Together by Age 14 & High Education) | |

| Parents Together & Low Education | 1.19 ** |

| Parents Not Together & Low Education | 1.79 *** |

| Parents Not Together & High Education | 1.51 *** |

| Mother Worked During Childhood & Mothers’ Education (ref=Mother Worked & High Education) | |

| Mother Worked & Low Education | 1.10 |

| Mother Did Not Work & High Education | .98 |

| Mother Did Not Work & Low Education | .87 |

| Number of Siblings* Fathers’ Education (ref=High Education) | 1.04 *** |

| Age at First Sex ≤ 15 & Fathers’ Education (ref=Age at First Sex > 15 & High Education) | |

| Age at First Sex > 15 & Low Education | 1.19 ** |

| Age at First Sex ≤ 15 & High Education | .00 |

| Age at First Sex ≤ 15 & Low Education | 2.15 ** |

| Interactions with Gender | |

| Parents Broke Up by Age 14 & Gender (ref=Parents Together by Age 14 & Male ) | |

| Parents Together & Female | 1.98 *** |

| Parents Not Together & Male | 1.48 *** |

| Parents Not Together & Female | 2.95 *** |

| Mother Worked During Childhood & Gender (ref=Mother Worked & Male) | |

| Mother Worked & Female | 2.03 *** |

| Mother Did Not Work & Male | .93 |

| Mother Did Not Work & Female | 1.75 *** |

| Number of Siblings* Gender (ref=Female) | .87 *** |

| Age at First Sex ≤ 15 & Gender (ref=Age at First Sex > 15 & Male) | |

| Age at First Sex > 15 & Female | 1.99 *** |

| Age at First Sex ≤ 15 & Male | 2.06 * |

| Age at First Sex ≤ 15 & Female | 4.02 *** |

p<.10

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

Note: NMB: Nonmarital birth. MB: Marital birth

These results are from a pooled sample for men and women and include all covariates. Each interaction model was estimated separately.

For simplicity, we refer to those whose fathers had a high school degree or less as low education and those whose fathers had some college or more as high education.

We also examine interactions by socioeconomic background, measured by fathers’ (and mothers’) education; for simplicity, those whose fathers had a high school degree or less are coded as low education and those whose fathers had at least some college as high education. Findings suggest that education plays an important role in the transmission of nonmarital childbearing: respondents from all other groups are at a significantly lower risk of having a nonmarital birth compared to those with low-educated fathers and whose parents were not married at their birth. In other words, being born outside of marriage and to a father with a high school degree or less seems to be a particularly deleterious combination for heightening one’s own risk of having a nonmarital first birth.

Next, given that socioeconomic background has been repeatedly linked to outcomes for the next generation, particularly with respect to family of origin characteristics and respondent’s early sexual behaviors (all of which are significantly associated with offspring’s nonmarital childbearing in Table 3), we examine whether the association between these characteristics and offspring’s nonmarital childbearing varied by fathers’ level of education. The results suggest that parents’ breaking up by the time offspring are age 14 significantly increases their risk of having a nonmarital first birth regardless of fathers’ education (although the hazard ratio is slightly larger for those from lower-SES backgrounds). While mothers’ employment increased the risk of offspring’s nonmarital childbearing in Table 3, it does not appear that mothers’ education moderates this relationship. Although, in additional analyses (not shown), we examine this interaction separately for men and women and find that women (but not men) whose mothers were both low educated and employed are at a significantly higher risk of having a nonmarital fisth birth compared to those whose mothers were employed and highly educated.3 This suggests that mothers’ employment is particularly deleterious at low levels of education for women, but not for men.

Along similar lines, the interaction between the number of siblings that respondents grew up with (this figure includes the respondent) and fathers’ education suggests that while having more siblings and a lower-SES background significantly increased the risk of offspring having a nonmarital first birth, the magnitude of this relationship is very small. The interaction between fathers’ education and whether or not offspring had sex at age 15 or younger suggests that regardless of when offspring had sex for the first time, SES background is more predictive of their risk of having a nonmarital first birth. On the other hand, offspring from low-SES backgrounds, who had sex at age 15 or younger, are nearly twice as likely to have a nonmarital first birth compared to those who were from higher-SES backgrounds and had sex later.

Turning now to the examination of gender as a moderator in Table 4, across all of the interactions, female offspring compared to male offspring are significantly more likely to have a nonmarital first birth. While the risk of men having a nonmarital birth increases if their parents broke up by age 14, the magnitude of this hazard ratio for women is statistically significantly larger (2.95 for women versus 1.48 for men). As is the case for the moderating effect of mothers’ education and employment, the results suggest that mothers’ employment is not associated with men’s risk of having a nonmarital first birth. The number of siblings men and women have significantly decreases men’s risk of having a nonmarital first birth compared to women’s, and compared to men who had sex for the first time after age 15, all others are at a higher risk of having a nonmarital first birth. Taken together, these results further show that women are at a significantly greater risk of having a nonmarital first birth compared to men.

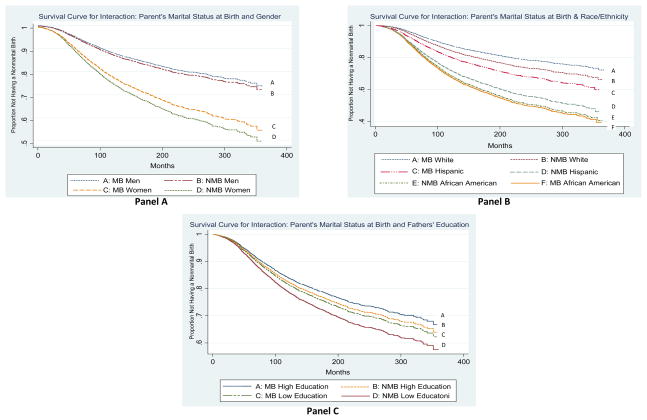

In order to provide a more intuitive presentation of the interaction results, Figure 2 shows survival curves for having a nonmarital first birth corresponding to the interaction models for gender, race, and parental education reported in Tables 3 and 4. Each set of survival curves shows the cumulative probability of respondents having a nonmarital first birth with exposure beginning at age 15. Panel A shows that women whose parents were not married when they were born represents the smallest proportion of the sample ‘surviving’ the period of exposure without having a nonmarital birth (line D); the greatest proportion surviving are men whose parents were married at their birth (line A), followed closely by women whose parents were married at their birth (line B). With respect to race/ethnicity, the group in Panel B most likely to survive the period of exposure without having a nonmarital first birth is Whites with married parents (line A), and the smallest proportion not having a nonmarital first birth is African Americans, regardless of parents’ marital status at their birth (lines E and F). Panel C, focused on paternal education, shows that those from low-education backgrounds and whose parents were unmarried at their birth are the least likely to survive the period of exposure without having a nonmarital first birth (line D), and those from high-education backgrounds whose parents were married at their births have the fewest nonmarital first births during the period of exposure (line A).

Figure 2.

Survival Curves for Interactions with Parents’ Marital Status at Respondents’ Birth

Notes : NMB: nonmarital birth. MB: marital birth. In Panel C, low education indicates a high school degree or less, and high education indicates some college or more.

5. Discussion

This paper examines how nonmarital childbearing is transmitted across generations. Retrospective histories using data from the NSFG were constructed to estimate the risk of a nonmarital first birth as a function of offspring’s being born to unmarried parents, parents’ socioeconomic background, family of origin characteristics, respondents’ characteristics, and a range of covariates. We extend prior research considering the link between family structure and nonmarital childbearing focused primarily on women, and a scant literature on early fatherhood, to include the intergenerational transmission of nonmarital childbearing for both men and women. No prior research (of which we are aware) has directly examined whether parents’ nonmarital childbearing is associated with offspring’s subsequent nonmarital childbearing.

Parents’ being unmarried at offspring’s birth significantly increases their risk of later having a nonmarital first birth, suggesting that the marital context of childbearing is indeed transmitted inter-generationally. Adjusting the models for parental socioeconomic background (measured by fathers’ and mothers’ education) only modestly diminishes the transmission of nonmarital childbearing from one generation to the next, suggesting that—in response to our first research question—nonmarital childbearing does have an effect on the next generation’s childbearing, independent of the socioeconomically-disadvantaged contexts in which nonmarital births typically occur. This result is inconsistent with research on early childbearing (Barber, 2001), which finds that the intergenerational transmission of young age at first birth is entirely accounted for by parental socioeconomic and other background factors. The difference may be due to the fact that Barber (2001) had a much richer set of parental characteristics (e.g., mother’s fathers’ education and occupation, mother’s religiosity, and mother’s contraceptive use) than are available to us in the NSFG. To the extent that other factors associated with socioeconomic status or social context (e.g., neighborhood characteristics) that are unavailable in the NSFG affect offspring’s risk of having a nonmarital first birth, our measure of parental education may underestimate the influence of SES background on respondent’s risk. Also, Barber was particularly focused on young age at birth, whereas we consider nonmarital childbearing at all ages. Our findings, however, are consistent with prior research on how family structure relates to the premarital childbearing of women (Wu and Martinson, 1993; Wu, 1996), i.e., some direct effect persists after accounting for fathers’ education.

The second research question concerns how any intergenerational transmission of nonmarital childbearing might operate via family of origin characteristics and/or respondent’s educational attainment and age at first sex. Consistent with prior research (Anderton et al., 1987; Barber, 2001), we found that the risk of offspring having a nonmarital first birth when their parents had a nonmarital birth was partially transmitted through parents’ breaking up by offspring’s age 14, one of our measures of family of origin characteristics. Young age at first sex is also an important mediating factor. Once these variables are included, the magnitude of the direct link in nonmarital childbearing across generations is smaller. However, even after including all of our mediating factors, being born to unmarried parents is still associated with an increased risk of offspring having their own first birth outside of marriage. While additional mechanisms cannot be evaluated, it is possible that social norms and values may be transmitted across generations such that offspring born to unmarried parents are more open to themselves having a child outside of marriage.

The third and final research question was to examine whether race, gender, and socioeconomic background moderated the relationship between parents’ marital status at respondents’ birth and respondents’ subsequent marital status at their first birth (as well as the potential mediators). The overall findings suggest that males are at a significantly decreased risk of having a nonmarital first birth compared to females, regardless of parents’ marital status at their births. These results could (partially) reflect men’s tendency to underreport (or forget) the number of nonmarital births that they have fathered (Rendall et al., 1999). Findings also suggest that African Americans are at a significantly increased risk of having a nonmarital birth compared to Whites, regardless of parents’ marital status at their births. This is largely consistent with South and Baumer (2000), who found that premarital childbearing among African Americans is linked to the circumstances associated with living in distressed, poor communities. On the other hand, without including community characteristics (which are unavailable because we do not have geographic identifiers in the NSFG), it is difficult to determine whether nonmarital childbearing is transmitted inter-generationally via families or through disadvantaged circumstances in poor communities.

As expected, having a higher socioeconomic background generally buffers those whose parents had a nonmarital birth against the risk of later having a nonmarital first birth. Findings further suggest that parents breaking up before age 14, the number of siblings respondents grew up with, and respondents’ having sex at age 15 or younger (mediating factors) varies significantly by SES background (measured as fathers’ education). Respondents from higher-SES backgrounds whose parents were still together by the time they were age 14 are at a significantly lower risk of having a nonmarital birth, even compared to lower-SES respondents whose parents stayed together. On the other hand, it is interesting to note that higher-SES respondents whose parents broke up by the time they were age 14 are at a higher risk than lower-SES respondents whose parents stayed together (although this group was still at a higher risk compared to higher-SES respondents whose parents were together at age 14). Taken together, these results suggest that while higher-SES respondents are generally buffered against having children outside of marriage, when their parents break up, the risk of their having a nonmarital birth significantly increases (although it remains lower than for low-SES respondents whose parents broke up).

The link between maternal employment and offspring nonmarital childbearing does not appear to be moderated by respondents’ SES background. On the other hand, when we examined men and women separately (results not shown), there was a significant difference between maternal employment and offspring nonmarital childbearing for women whose mothers have limited education and were employed during their childhood. This was not the case for men. This suggests that women whose mothers have low education and work during their childhood may be more vulnerable to their mothers’ absence from the home than are higher-SES women and all men—something noteworthy as a topic for future research.

In all of the gender interactions, including our mediating factors, women were at a higher risk of having a nonmartial first birth than men. This finding is particularly interesting given that men and women bear children together. Given this fact, we would expect men and women to look more similar in their childbearing behaviors. Men’s general underreporting of the number of nonmarital births they have had may account for the differences that we observe in this study. It may also be that men’s and women’s childbearing timing is different, and thus we are more likely to observe differences in their risk of having a nonmarital first birth. In addition, men’s and women’s childbearing behaviors may be affected by different factors which have not been accounted for in these analyses. For example, SES background, mothers’ employment, and age at first sex appear less predictive of men’s nonmarital first births compared to women, but it may be that other contextual characteristics, such as neighborhood characteristics or peers, are more salient for men.

It is important to note the limitations of this study. First, as inferred above, the scope of the family background questions limits what we know about parents. Because the NSFG is largely concerned with fertility and health, there is no information provided about parents’ occupation, early income, neighborhoods, or attitudes and beliefs regarding childbearing, which would be useful for this study. These analyses are thus restricted to using parents’ education as the primary measure of socioeconomic background. In terms of other potential mechanisms, measures of parents’ income (or changes in parental income) during men’s and women’s childhood or adolescence and parental relationships and parenting behaviors are unavailable. The family structure literature suggests that income and parenting are the primary mechanisms by which single parenthood after divorce influences child and adolescent outcomes (Thomson et al., 1994); we suspect the same may be true for nonmarital childbearing (given the increased risk of instability that follows), but this cannot be tested here. Furthermore, the independent variable is limited to the marital status of respondents’ parents at their birth; therefore, it is difficult to determine whether respondents were born into a single-parent household or whether both, cohabiting parents, were present. We do, however, examine whether or not respondents’ parents (i.e., those who were married and unmarried at their births) were together by the time they were age 14 and thus the likelihood that respondents spent time in a single-parent home during their childhood.

This study is further limited to retrospective reports from cross-sectional data, which were used because information was available on parents’ marital status at offspring’s birth (unlike many studies). Nonetheless, cross-sectional data do not allow us to investigate the process leading to offspring’s nonmarital first births, nor does it allow us to reduce potential bias associated with men’s underreporting of nonmarital first births. On the other hand, prior research (Martinez et al., 2006) suggests that this is less worrisome in the NSFG than in other studies (Rendall et al., 1999). Despite these limitations, this study sheds new light on nonmarital childbearing by adding to the literature a direct empirical investigation of whether parents’ having a nonmarital birth increases the risk of their children later having a nonmarital first birth.

The increasing prevalence of nonmarital childbearing and the instability of these relationships (Beck et al., 2010), the absence of fathers (Tach, Mincy, and Edin, 2010), and the economic hardship (Nock, 1998) which tend to follow nonmarital births have important implications for the well-being of future generations. To the extent that having a nonmarital first birth is associated with negative outcomes for children even as they become adults (Haveman, Wolfe, & Pence, 2001), the intergenerational transmission of nonmarital childbearing may reinforce other social forces affecting poverty and inequality today (e.g., the availability of low-wage work, educational opportunities, neighborhood disadvantage, etc.), particularly for women. On the other hand, if parents’ nonmarital childbearing itself results entirely from preexisting disadvantages (selection factors) set in place when children are born, future research (using rich measures of parental background characteristics) should attempt to disentangle these effects in order to better understand the most salient risk factors associated with nonmarital childbearing for the next generation and its consequences.

Highlights.

Nonmarital childbearing is transmitted across generations.

The intergenerational transmission exists net of confounding characteristics.

Parental breakups by age 14 and young age at first sex mediate the relationship.

Several mediating factors vary by socioeconomic background.

Gender, race/ethnicity, and parental education moderate the transmission.

Acknowledgments

This research was carried out using the facilities of the Center for Demography and Ecology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. The first author’s time on this paper was supported by an NICHD postdoctoral fellowship (#R24HD047873) and by an ARRA supplement to the NICHD grant supporting the second author’s time on this paper (#R01HD57894). The authors would like to thank participants in the Demography Seminar at the University of Wisconsin-Madison (including Calvina Ellerbe, Ted Gerber, Jim Raymo, Jason Thomas, Kimberly Turner, Alicia VanOrman, and Jim Walker) and Heather Koball for helpful comments.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aassve A. The Impact of Economic Resources on Premarital Childbearing and Subsequent Marriage among American Women. Demography. 2003;40(1):105–126. doi: 10.1353/dem.2003.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aassve A, Burgess S, Chesher A, Propper C. Transitions from home to marriage of young Americans. Journal of Applied Econometrics. 2002;17(1):1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht C, Teachman JD. Childhood Living Arrangements and the Risk of Premarital Intercourse. Journal of Family Issues. 2003;24:867–894. [Google Scholar]

- Allison PD. Survival Analysis Using SAS: A Practical Guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Amato P. Family Processes in One-Parent, Stepparent and Intact Families: The Child’s Point of View. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1987;49(2):327–337. [Google Scholar]

- Amato PR. Explaining the Intergenerational Transmission of Divorce. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1996;58:628–640. [Google Scholar]

- Barber JS. The Intergenerational Transmission of Age at First Birth among Married and Unmarried Men and Women. Social Science Research. 2001;30:219–247. [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. Effects of Authoritative Parental Control on Child Behavior. Child Development. 1966;37(4):887–907. [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. Authoritarian versus Authoritative Parental Control. Adolescence. 1986;3:255–272. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AN, Cooper CE, McLanahan SS, Brooks-Gunn J. Relationship Transitions and Maternal Parenting. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72:219–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00695.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker GS. A Treatise on the Family. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson VL. Generation and Family Effects in Value Socialization. American Sociological Review. 1975;40(3):358–371. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson VL, Allen KR. The Life Course Perspective Applied to Families Over Time. In: Boss P, Doherty WJ, LaRossa R, Schumm WR, Steinmetz SK, editors. Sourcebook of Family Theories and Methods: A Contextual Approach. New York: Springer US; 1993. pp. 469–504. [Google Scholar]

- Berger L, Paxson C, Waldfogel J. Income and Child Development. Children and Youth Services Review. 2009;31:978–989. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2009.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bumpass L, McLanahan S. Unmarried Motherhood: Recent Trends, Composition, and Black - White Differences. Demography. 1989;26(2):279–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bumpass LL, Martin TC, Sweet JA. The Impact of Family Background and Early Marital Factors on Marital Disruption. Journal of Family Issues. 1991;12(1):22. doi: 10.1177/019251391012001003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson MJ, Furstenberg FF., Jr The Prevalence and Correlates of Multipartnered Fertility among Urban U.S. Parents. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2006;68(3):718–732. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson MJ, VanOrman A, Pilkauskas N. Examining the Antecedents of US Nonmarital Fatherhood. University of Wisconsin-Madison; 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diekmann A, Schmidheiny K. The Intergenerational Transmission of Divorce: A Fifteen-Country Study with the Fertility and Family Survey. Swiss Federal Institute of Technology; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll AK, Hearn GK, Evans VJ, Moore KA, Sugland BW, Call V. Nonmarital Childbearing Among Adult Women. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1999;61:178–187. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J. The Consequences of Growing Up Poor. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH., Jr Time, Human Agency, and Social Change: Perspectives on the Life Course. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1994;57(1):4–15. [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH., Jr The Life Course as Developmental Theory. Child Development. 1998;69(1):1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forste R, Jarvis J. “Just Like His Dad”: Family Background and Residency with Children among Young Adult Fathers. Fathering. 2007;5(2):97–110. [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg FF. Race Differences in Teenage Sexuality, Pregnancy, and Adolescent Childbearing. The Milbank Quarterly. 1987;65(2):381–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg FF, Jr, Weiss CC. Intergenerational Transmission of Fathering Roles in At Risk Families. Marriage and Family Review. 2000;29(2/3):181–201. [Google Scholar]

- Furstenberg FF, Kiernan KE. Delayed Parental Divorce: How Much Do Children Benefit? Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2001;63(2):446–457. [Google Scholar]

- Goldscheider F, Hofferth S, Spearin C, Curtin S. Fatherhood Across Two Generations: Factors Affecting Early Family Roles. Journal of Family Issues. 2009;30(5):586–604. doi: 10.1177/0192513X08331118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottschalk P. The Intergenerational Transmission of Welfare Participation: Facts and Possible Causes. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 1992;11(2):254–272. [Google Scholar]

- Graefe DR, Lichter DT. Life Course Transitions of American Children: Parental Cohabitation, Marriage, and Single Motherhood. Demography. 1999;36(2):205–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzzo KB, Furstenberg FF., Jr Multipartnered Fertility among American Men. Demography. 2007;44(3):583–601. doi: 10.1353/dem.2007.0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzzo KB, Hayford SR. Single Mothers, Single Fathers: Gender Differences in Fertility after a Nonmarital Birth. Journal of Family Issues. 2009;0:1–28. doi: 10.1177/0192513X09351508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haveman R, Wolfe B, Pence K. Intergenerational Effects of Nonmarital and Early Childbearing. In: Wu LL, Wolfe B, editors. Out of Wedlock: Cause and Consequences of Nonmarital Fertility. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman SD, Foster EM. Economic Correlates of Nonmarital Childbearing Among Adult Women. Family Planning Perspectives. 1997;29(3):137–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan DP, Kitagawa EM. The Impact of Social Status, Family Structure, and Neighborhood on the Fertility of Black Adolescents. American Journal of Sociology. 1985;90(4):825–855. [Google Scholar]

- Högnäs RS, Carlson MJ. Coparenting in Fragile Families: Understanding How Parents Work Together after a Nonmarital Birth. In: McHale JP, Lindahl KM, editors. Coparenting: A Conceptual and Clinical Examination of Family Systems. Washington, D.C: American Psychological Association; 2011. pp. 81–103. [Google Scholar]

- Joyner K, Peters E, Hynes K, Sikora A, Taber JR, Rendall MS. The Quality of Male Fertility Data in Major U.S. Surveys. Demography. 2012;49 (1):101–124. doi: 10.1007/s13524-011-0073-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krein S, Beller A. Educational Attainment of Children from Single-Parent Families: Differences by Exposure, Gender, and Race. Demography. 1988;25(2):221–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman RI. A National Profile of Young Unwed Fathers. In: Lerman RI, Ooms TJ, editors. Young Unwed Fathers: Changing Roles and Emerging Policies. Philadelphia: Temple University Press; 1993. pp. 27–51. [Google Scholar]

- Li JCA, Wu LL. No Trend in the Intergenerational Transmission of Divorce. Demography. 2008;45(4):875. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglio W. Adolescent Fathers in the United States: Their Initial Living Arrangements, Marital Experience and Educational Outcomes. Family Planning Perspectives. 1987;19(6):240–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ, Osterman MJK, Kirmeyer S, Matthews TJ, et al. Births: Final Data for 2009. 1. Vol. 60. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez GM, Chandra A, Abma JC, Jones J, Mosher WD. Fertility, Contraception, and Fatherhood: Data on Men and Women from Cycle 6 of the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statisticso. Document Number); 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan S. Family Instability and Complexity after a Nonmarital Birth: Outcomes for Children in Fragile Families. In: Carlson MJ, England P, editors. Social Class and Changing Families in an Unequal America. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan S, Bumpass L. Intergenerational Consequences of Family Disruption. American Journal of Sociology. 1988;94(1):130–152. [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan S, Sandefur G. Growing Up with a Single Parent: What Hurts? What Helps? Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Muller C. Maternal Employment, Parent Involvement, and Mathematics Achievement among Adolescents. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1995;57(1):85–100. [Google Scholar]

- Musick K, Meier A. Are Both Parents Always Better Than One? Parental Conflict and Young Adult Well-Being. Social Science Research. 2010;39(5):814–830. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock SL. The Consequences of Premarital Fatherhood. American Sociological Review. 1998;63:259–263. [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer VK. A Theory of Marriage Timing. American Journal of Sociology. 1988;94(3):563–591. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne C, McLanahan S. Partnership Instability and Child Well-Being. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2007;69(4):1065–1083. [Google Scholar]

- Pears KC, Pierce SL, Kim HK, Capaldi DM, Owen LD. The Timing of Entry Into Fatherhood in Young, At-Risk Men. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67(2):429–447. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-2445.2005.00126.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers DA. Alternative Models of the Effects of Family Structure on Early Family Formation Social Science Research. 1993;22(3):283–299. [Google Scholar]

- Rendall MS, Clarke L, Peters HE, Ranjit N, Verropoulou G. Incomplete Reporting of Men’s Fertility in the United States and Britain: A Research Note. Demography. 1999;36(1):135–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruhm C. Maternal Employment and Adolescent Development. Labour Economics. 2008;15(5):958–983. doi: 10.1016/j.labeco.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigle-Rushton W, McLanahan S. Father Absence and Child Well-Being: A Critical Review. In: Moynihan DP, Smeeding TM, Rainwater L, editors. The Future of the Family. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2004. pp. 116–155. [Google Scholar]

- Sipsma H, Biello KB, Cole-Lewis H, Kershaw T. Like Father, Like Son: The Intergenerational Cycle of Adolescent Fatherhood. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(3):517–524. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.177600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- South SJ, Baumer EP. Deciphering Community and Race Effects on Adolescent Premarital Childbearing. Social Forces. 2000;78(4):1379–1408. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson E, Hanson TL, McLanahan SS. Family Structure and Child Well-Being: Economic Resources vs. Parental Behaviors. Social Forces. 1994;73(1):221–242. doi: 10.1093/sf/sos119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry TP, Smith CA, Howard GJ. Risk Factors for Teenage Fatherhood. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1997;59(3):505–522. [Google Scholar]

- Trent K. Family Context and Adolescents’ Expectations about Marriage, Fertility, and Nonmarital Childbearing. Social Science Quarterly. 1994;75(2):319–339. [Google Scholar]