Abstract

Retrospective questions on educational attainment in national surveys and censuses tend to over-estimate high school graduation rates by 15 to 20 percentage points relative to administrative records. Administrative data on educational enrollment are, however, only available at the aggregate level (state, school district, and school levels) and the recording of inter-school transfers are generally incomplete. With access to linked individual-level administrative records from a very large “West Coast metropolitan school district” we track patterns of high school attrition and on-time high school graduation of individual students. Even with adjustments for the omission of out-of-district transfers (estimates of omission are presented), the results of this study show that failure in high school, as indexed by retention and attrition, are almost as common as on-time high school graduation. In addition to the usual risk factors of disadvantaged background, we find that the “9th grade shock”—an unpredicted decline in academic performance upon entering high school—is a key mechanism behind the continuing crisis of high school attrition.

Introduction

The near universality of high school graduation is considered one of the major achievements of the American education system. Social indicators, based on survey and census data, show that high school completion has risen from about 50% of young adults in mid-20th century America to almost 90% among recent cohorts (Ingels, Curtin, Owings, Kaufman, Alt and Chen 2002: 14, Mare 1995: 162; Stoops 2004: 2). Thus, it came as a surprise several years ago when studies reported that only 65% to 70% of high school students actually earned a high school diploma (Balfanz and Legters 2004, Orfield 2004, Swanson 2004). These findings renewed debates over the high school dropout crisis, “dropout factories,” and policies to reform and restructure American high schools.

Much of the controversy was fueled by statistical measurement—or differences in how to define and measure high school graduation. Until a few years ago, the expert opinion was that retrospective questions from household surveys and censuses on completed schooling—highest level of education—yielded reliable and valid measures of high school graduation. However, more recent studies based on administrative records of enrolled students, report a more dismal picture with the “on-time high school graduation rate” about 15 to 20 percentage points lower than survey-based estimates (Greene and Winters 2002, Laird, DeBell, and Chapman 2006, Seastrom, Heckman and LaFountaine 2007, Hoffman, Chapman, and Stillwell 2005, Warren 2005, Warren and Halpern-Manners 2007, 2009). There are several reasons for the discrepancy between administrative and survey estimates of high school graduation, but the most important is the conflation of the receipt of a high school diploma and a high school equivalency certification (e.g. GED). Although about one-half of high school dropouts eventually receive some sort of alternative certificate of high school completion, a “real” high school diploma is worth considerable more in the labor market (Cameron and Heckman 1993, Heckman and LaFontaine 2006).

Not only do surveys and administrative records differ in their estimates of the prevalence of the high school graduation, but also their explanations of why students do not complete high school. Survey-based research emphasizes how individual level “risk factors” such as social class of origin, race/ethnicity, and gender influence educational opportunities and achievements (Featherman and Hauser 1976, Hauser 2004). Administrative data, based on school records, hold the potential to relate educational outcomes with the social organization of schooling and academic performance—factors that are difficult, if not impossible, to measure in standard household surveys of individuals and families. However, many sources of administrative data, such as the National Center for Educational Statistics’ (NCES) Common Core of Data (CCD) are typically published (or released) for aggregate units, such as schools, which do not allow for the analysis of the joint and interdependent effects of institutional and student characteristics on schooling outcomes.

In this study, we illustrate the potential of micro-level analysis of linked administrative records to investigate the determinants of high school graduation as well as the cumulative processes of promotion, retention, and attrition of students for six years after entry into 9th grade. Our analysis is based on records of nearly 9,000 high school students in a large West Coast metropolitan school district from 1994 to 2005 These data contain a wealth of individual level risk factors in addition to measures of academic performance and placement. With the universe of all students in the school system, we are able to track each student from the time they enter the school system until they leave the system or graduate. The results reported here confirm and expand upon those reported from similar studies in Chicago (Allensworth and Easton 2005), Philadelphia (Balfanz et al. 2007) and other school districts (Gleason and Dynarski 2002). Moreover, the findings presented here—particularly on the “9th grade shock” (a dramatic drop in academic performance upon entering high school)—provide new insights into the reasons for the persisting crisis of high school attrition.

Because of the contested and often confusing literature on attrition and graduation in American high schools, we begin with an overview of the conceptual and measurement problems of research on high school dropout and graduation. Then we turn to the analysis with two objectives in mind. The first is to offer a detailed description of the widespread patterns of failure in high school with a life-table model of the major pathways of progression, retention, and attrition. Although it is possible for high school students to recover from failure, in fact, very few actually do.

The second objective is to estimate a model of on-time high school graduation that highlights the role of early academic performance in high school as a critical mediating variable between social background and high school graduation. We find that many students encounter failure (not predicted by middle school academic performance) during their first term in high school. Students from disadvantaged backgrounds are particularly susceptible to the “ninth grade shock,” but low grades in the first year of high school are far more pervasive and consequential than what would be predicted from background variables alone. In the concluding section of the paper, we review the range of possible explanations for why so many students stumble upon entering high school.

Measuring High School Dropouts and Completion

Until a few years ago, there was a remarkable consensus on the success of American high school graduation rates. Every national study based on household survey and census data shows an upward trend in high school completion over the course of the 20th century (Duncan 1968: 655, Fischer and Hout 2006: 13, Fox, Connolly and Snyder 2005: 48, Hauser 1997: 161, Mare 1995: 162, Mare and Winship 1988: 182). The wording or format of survey questions on educational attainment can have modest effects on estimates of high school graduation rates, but the overall story is consistent across varied data sources (Hauser 1997: 162-167, Mare 1995, Scanniello 2007). The general picture is illustrated by the top line in Figure 1 (from a Census Bureau report) which shows that the proportion of successive cohorts (measured at age 25 to 29) graduating from high school rose steadily from around 50% to about 85 or 90% before leveling off. Estimates of the high school dropout rate based on school enrollment (and non-enrollment) of adolescents and young adults from household surveys are roughly comparable to those based on retrospective reports of completed educational attainment (Kominski 1990). Since the small number of high school dropouts could well be explained by idiosyncratic characteristics of individuals, the attention of many educational researchers shifted from the historical focus on high school completion to the problems of the transition to college and college completion (e.g. Charles et al. 2009, Kirst and Venezia 2004, Massey et al. 2003).

Figure 1. Educational Attainment of the Population 25 Years and Over by Age: 1947 to 2003.

Note: prior 1964, data are shown for 1947, 1950, 1952, 1957, 1959, and 1962.

Sourece: U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey and the 1950 Census of of Population.

Source: Stoops, Nicole. 2004. “Educational Attainment in the United States: 2003” Current Population Reports P20-550. Washington, DC: U.S. Bureau of the Census.

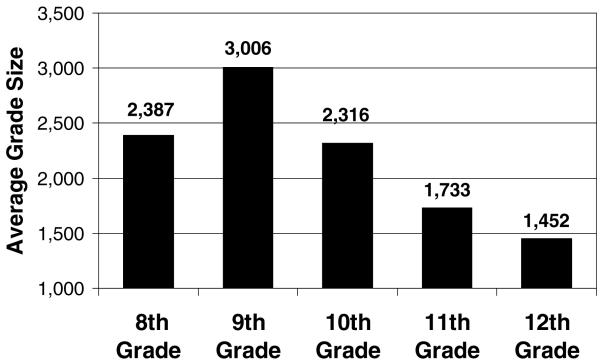

This consensus, however, was at odds with the experiences in many school districts where the dropout problem is clearly evident. This counter view is illustrated by the high school enrollment patterns in the West Coast metropolitan school district that is the focus of this study. Figure 2, based on enrollment data, shows that there are typically 3,000 students in the 9th grade freshman class, but only half of that number—less than 1,500 students—is enrolled in the senior class. These data are cross-sectional, but are averaged over 7 years (1996 to 2002) to adjust for annual fluctuations in enrollment. Admittedly, there is a 9th grade “bulge,” relative to 8th grade enrollment, because of in-transfers and retentions, but the evidence of massive numbers of dropouts would be only slightly reduced if seniors are compared to 8th graders in the school system. Although Figure 2 is based on only one school district, which has an above average high school dropout rate (Bylsma and Ireland 2005), these data are similar to many high schools (and school districts) around the country that have considerably fewer seniors than freshman and sophomores. National data based on administrative records tell a similar story, though the ratio of high school seniors to freshmen four years earlier is somewhat higher than our West Coast metropolitan school district (Warren and Halpern-Manners 2007, National Center for Education Statistics 2011).

Figure 2.

Students enrolled, by Grade Level: Averages for Academic Years from 1997-98 to 2004-05.

Source: Merged grade history files (MRDF) of enrolled students from 1997-98 to 2004-05 in a West Coast metropolitan school district.

Notes: These figures are the numbers of enrolled students in the fall semester of each academic year, averaged across 8 academic years.

The National Center for Educational Statistics, which is the primary research agency of the U.S. Department of Education, collects and tabulates administrative records of educational enrollment and high school graduates from almost all public school districts and state educational agencies in the United States (see: http://nces.ed.gov/ccd/). These data, known as the Common Core of Data (CCD) have been the source of the resurgent attention on the much-higher-than-expected rate of high school dropout, particularly among racial and ethnic minorities (Greene and Winters 2002; Swanson 2004; Seastrom, Hoffman, Chapman, and Stillwell 2005, Laird, DeBell and Chapman 2006, Warren 2005, Stillwell 2009, Heckman and LaFontaine 2010). Although the figures vary slightly from year to year and from method to method, the major conclusions from these studies are: 1) the “true” national high school graduation rate is around 70%, 2) there has been little progress in narrowing race and ethnic differentials, and 3) there appears to have been a slight decline in the high school graduation rate in recent years. All these “facts” stand in sharp contrast to the dominant narrative from studies based on census and national survey data that show almost universal high school completion, declining rates of high school dropout, and a narrowing of race and ethnic differentials.

In the last few years, there have been several authoritative studies that attempt to reconcile the reasons for the differences in estimates of levels and trends in high school graduation based on the Current Population Survey (CPS), a household survey conducted by the Census Bureau, and administrative records—the NCES Common Core of Data (Heckman and LaFontaine 2010, Warren and Halpern-Manners 2007, 2009, Hauser and Koenig 2011). There are major differences in population coverage between national household surveys (e.g., Current Population Survey) and administrative records (e.g., CCD), but most of the gap in reported estimates of high school graduation is due to differences in the definition and measurement of high school enrollment and graduation.

Household surveys, such as the Current Population Survey (CPS), are subject to “under-coverage” (undercount) of persons who are more likely to be high school dropouts. Estimates of the under-coverage (those not interviewed) of 16 to 19 year old males in the Current Population Survey were 10% of whites, 16% of blacks, and 13% of Hispanics (U.S Census Bureau 2002: 16-2). Although CPS data are weighted to adjust for under-coverage by age, sex and race/ethnicity, the adjusted data rely on the questionable assumption that the characteristics of those not interviewed in each population segment are similar to persons who are interviewed in the same group (Kaufman 2004: 116). Another problem is that the non-household population is excluded from the Current Population Survey. This was a minor problem in 1970, when CPS estimates of high school graduation were very similar to estimates from the decennial US census, which includes the non-household population. But by 2000, the CPS estimates, when compared to Census Bureau estimates, over-estimated high school graduation by roughly 10% for all young adults ages 20 to 24 (Heckman and LaFontaine 2010). CPS estimates of high school graduation rates of African Americans are biased upwards by 18% because of the exclusion of the non-household population, primarily those in prisons and jails (Heckman and LaFontaine 2010). The CPS estimate of Hispanic high school graduation rate is biased downwards by the inclusion of young immigrants who were never enrolled in American schools (Oropesa and Landale 2009).

The major reason for the upward bias of educational responses in household surveys is the conflation of high school graduation and high school equivalency certification. The popular understanding of high school graduation is four years of continuous enrollment in high school and the receipt of a high school diploma—which we label as “on time high school graduation.” What is reported in most household surveys, however, is “high school completion,” which includes alternative credentials. The standard retrospective educational attainment questions in most surveys do not differentiate between the types and timing of high school completion. Until 2008, one of the standard response categories of the educational attainment question in the census, CPS, and the ACS (American Community Survey) questionnaires was: “High School Graduate—high school diploma or the equivalent (for example, GED).” The 2008 American Community Survey was the one of the first national household surveys to ask respondents to distinguish between high school graduation and alternative certification (Fry 2010).

Heckman and LaFontaine (2010: 247) note that the percentage of high school credentials awarded by equivalency programs rose from 2% to 15% in recent years. Some GED’s may be counted in administrative records such as the CCD, (if they are awarded by regular high schools), but the bias is much more common in survey data. When directly asked about having a GED (or other alternative certifications of high school completion), about 9 percent of NELS (National Educational Longitudinal Survey) respondents (at age 22) reported they had completed high school, but did not receive a standard high school diploma (Ingels, Curtin, Owings, Kaufman, Alt and Chen 2002: 14)1.

Most individuals appear to consider the successful completion of high school equivalency programs as equal to an on-time high school diploma. The reality is, however, that a GED is not equivalent to a high school diploma. Most GED recipients are dropouts from regular high schools who resume their schooling in a community college, the military, or in prison. Moreover, the employment patterns and earnings of GED recipients are more similar to high school dropou ts than those of high school graduates, and GED recipients are less likely than high school graduates to finish a post-secondary education or training program (Cameron and Heckman 1993, Heckman and LaFontaine 2006, Heckman and Rubenstein 2001, Tyler 2003).

Another measurement problem is the over-reporting of educational enrollment and attainment in surveys. In a thorough analysis of measurement problems, Warren and Halpern-Manners (2007) find that some CPS (and other survey) respondents (presumably parents) report that adolescents in the household (their children) are enrolled in higher grade levels than they have attained. For example, if a child has been retained, many parents report the child as enrolled in the grade they should be in rather than in their actual (retained) grade. Using a small subset of NELS respondents that had dropped out of school (and did not report a high school credential), Warren and Halpern-Manners (2009) find that 25% of the dropouts’ parents reported that their child was still enrolled in school.

Individuals also appear to exaggerate their own educational credentials. Hauser (1997: 165) finds a consistent pattern of a 4 to 5 percentage point increase in the proportion of a cohort reporting high school completion from age 19-20 to their mid to late 20s. Any increase in high school completion above age 19 is almost certainly due to alternative certification programs or exaggeration.

The underlying problem is that high school attrition is not a clearly defined event. What may begin as a spell of absenteeism may be the first step toward dropping out. For a long period, neither the school nor the student may know if a spell of missed schooling is a temporary or permanent interruption in schooling. There is a lot of “churning” with students floating in and out of regular schools, alternative schools, remedial programs, and high school equivalency programs run by school districts or community colleges. Administrative records of enrollment are generally based on students who regularly attend school, but some dropouts are included if they are attending alternative programs. In some school districts and states, diplomas are awarded to students who complete equivalency programs. Problems of measurement are compounded in survey reports when respondents conflate years attended with grade level attained and high school equivalency with high school graduation.

The current weight of evidence is that administrative data provide a more accurate picture of high school graduation levels than do household surveys (Warren and Halpern-Manners 2007, 2009, Hauser and Koenig 2011). But since administrative data, such as the CCD, are generally available only for aggregate units, such as schools, individual-level survey data will remain the backbone of educational research. In this study, we show the promise of micro-level administrative data, linked across years, to study student trajectories through high school. In addition to the standard survey measures of individual-level risk factors, detailed administrative records allow us to pinpoint the impact of early academic performance (retention, GPA) on high school progression and on-time high school graduation.

Theories and Models of High School Attrition and Completion

There is an extensive research literature on the correlates and causes of high school dropout, largely based on survey data (Rumberger 1987, 2004, Hauser and Koenig 2011). Given that surveys excel at measuring individual-level characteristics, many studies find a long list of individual “risk factors” that are associated with above average rates of academic failure and dropout. For example, African American, Native American, and Hispanic, as well as students born outside of the United States, and male students have above-average dropout rates (Freeman and Fox 2005, Kaufman, Alt, and Chapman 2004, Wojtkiewicz and Donato 1995). Socioeconomic status (SES), typically measured by parental education, occupational status, or income is one of the strongest and most consistent correlates of dropping out (Alexander, Entwisle and Kabbani 2001, Lareau 2003, Rumberger 1983, 1987). Moreover, adolescents from single parent families and those with high rates of residential mobility display a higher risk of educational failure (Astone and McLanahan 1991, McLanahan and Sandefur 1994, Rumberger and Larson 1998).

There are two major limitations in the voluminous literature on survey-based studies of individual-level risk factors and schooling outcomes. The first is the need to sort out the inter-relationships among the long list of potential causes, correlates, and mechanisms that affect student educational attainment. Many of these factors are not independent of each other. The second major limitation of many surveys is the “individualistic perspective” that isolates students and their families from communities and school settings (Rumberger 2004). Addressing these issues requires new models and data sources.

The most important conceptual breakthrough has been the formulation of the life course perspective that attempts to measure the events and influences over the span of years from childhood to adolescence (Alexander, Entwisle and Kabbani 2001, Balfanz, Herzog, and MacIver 2007, Ensminger and Slusacick 1992, Garnier, Stein, and Jacobs 1997). The life course perspective posits that dropping out of school is not an isolated event; rather, it is the culmination of a process of academic failure and disengagement that begins early in the student’s academic career. Distal forces, including family background and preschool experiences can shape and condition the proximate events that lead to academic failure and dropping out in high school. Moreover, the effects of social background on educational continuation differ at successive stages of educational careers (Mare 1981). For example, the influence of socioeconomic status of the family of origin has been found to affect high school graduation through a myriad of mechanisms, including the availability of additional educational resources (Ainsworth 2002), educational expectations (Entwistle, Alexander, and Olson 2004), parenting styles, and parental attitudes (Rumberger, Ghatak, Poulus, Ritter, and Dornbusch 1990, Alexander, Entwisle, and Dorsey 1997). The impact of changes in family structure on educational failure is contingent on residential mobility and student’s age (Astone and McLanahan 1991, 1994, Alexander, Entwisle, and Dorsey 1997, Haveman, Wolfe, and Spaulding 1991, Sandefur, McLanahan, and Wojtkiewicz 1992).

The life course framework is generally used to create the temporal order of family background variables and early life experiences with data gathered from retrospective survey questions. However, not all prior events, especially their timing, can be reliably recalled in retrospective surveys. This issue is particularly germane to the policy debate over the impact of academic performance and retention on high school dropout. Adults may be able to recall the fact of school retention many years later, but the details of timing, prior academic performance, and spells of poor attendance are much less likely to be accurately recalled in retrospective surveys. Because of the problem of recall in retrospective surveys, life course models are largely dependent on prospective studies or longitudinal data collection that begins with contemporaneous reports of school performance and experiences. In addition to mediating the effects of family origins, school performance (measured by grades) in primary and middle school has been found to strongly predict dropping out of high school, net of other risk factors (Alexander, Entwisle and Dorsey 1997, Balfanz, Herzog, and Mac Iver 2007, Ekstrom, Goertz, Pollack and Rock 1986).

The availability of data on academic performance in administrative records or from survey data matched to school transcripts has led to innovative studies that combine individual and instructional influences on high school dropout (Lee and Burkam 2003, Rumberger and Palardy 2005, Rumberger and Thomas 2000). In addition to measures of academic performance, administrative data can also allow for the impact of the structure and character of schools with student attrition. Inner city public high schools, especially those with concentrations of minority and low income students, have much higher dropout rates than private and suburban schools (Bryk and Thum 1989, Hauser, Simmons, and Pager 2004, Rumberger 1995, Rumberger and Thomas 2000). The ability to match students with tracking data from school transcripts and administrative records has revealed complex aggregate and individual level pathways that can both reinforce and reduce preexisting patterns of socioeconomic and race/ethnic stratification (Alexander et al. 1978, Gamoran 1992a, 1992b, Gamoran and Mare 1989). Lee and colleagues have emphasized the potential impact of the size and structure of secondary schools on educational outcomes (Lee and Smith 1995, Lee and Burkham 2003). Large schools are hypothesized to be more anomic with less contact and rapport between students and teachers (Lee 2000).

Drawing upon both the individual and school-level traditions of research, we analyze the longitudinal records of individual students to measure the influence of social, demographic, and economic risk factors on the level and timing of high school attrition as mediated by academic progress, including grades, placement, and prior retention. Matched administrative records of individual students allow us to pinpoint the distal and proximate impact of academic failure over the course of high school careers.

We highlight two major findings—a remarkably high prevalence of failure in high schools and the causal impact of early academic failure—the 9th grade shock—in predicting successful on-time graduation. Earlier research has shown that many school transitions, both regular changes following the completion of primary and middle schools, as well as between-school transfers tend to be associated with decreased levels of academic performance for many students (Camburn, 1993, Schiller 1999, Swanson and Schneider 1999). The transition to high school is perhaps the most critical stage of students’ educational careers (Stevenson et al. 1994). Roderick and Camburn (1999) find that over 40% of students entering high school in Chicago failed a major course during the first semester of 9th grade. Few of these students ever recover from early failure. Overcoming the 9th grade shock is particularly difficult for students who displayed average to lower levels of performance in middle school (Langenkamp 2010). Our analysis extends earlier research with a focus on the transition to the 9th grade as both a key mediating variable of social disadvantage and as a major causal variable affecting high school graduation that is independent of all measured background variables.

Data

This study is based on unit-record school enrollment data from 1996 to 2005 for a large West Coast metropolitan school district. School records are maintained primarily for administrative needs, including the counts of students that are required to allocate budgets, teachers, and other resources within districts as well as to apply for financial support from state and federal governments. Student records include courses taken, grades received, and credits accumulated as well as demographic characteristics supplied by students and their families plus additional information from teachers, counselors, and administrators2. These materials provide both a rich array of background characteristics that are typically considered risk factors, as well as detailed data on academic performance.

With unique identifiers, individual student records were matched from semester to semester and from year to year. Normal high school progression is based on the assumption that entering 9th grade students who satisfactorily complete academic requirements are promoted to 10th grade, 11th grade and 12th grade in successive years, and graduate at the end of their senior (12th grade) year. However, normal high school progression does not characterize the measured trajectories of many students. Students who do not attain sufficient credits during the school year to merit promotion to the next grade level (typically because of failure) are administratively recorded in the grade below their expected level. It is possible for retained students to catch up to their expected grade level through summer school enrollment or by taking an extra course(s) during the academic year.

The data include four cohorts of students who first enrolled in the 9th grade in the school district from 1996 to 1999. With enrollment records from 1996 to 2005, we were able to track every student for at least 6 years after entering 9th grade. After careful scrutiny of the enrollment and attrition patterns across cohorts revealed only slight variations, we merged the four cohorts to create a population of 8,948 students from the time of first enrollment in high school (9th grade) until they graduated or exited from the database. Entrants into 9th grade only include “first time” 9th graders in order to avoid double counting students who were retained. For the descriptive analysis, we use the full sample of 8,948 first-time 9th graders, but the multivariate analysis is limited to the sample of 7,441 first-time 9th graders that also completed 8th grade in this school district (because 8th grade GPA is only reported for students who were enrolled in 8th grade in the district).

Exit as a Proxy for High School Attrition

The major limitation of administrative records is the inability to track students who exit from the universe of enrolled students. This is a major problem for national-level studies based on aggregate level data as well as local studies based on individual-level student records. Students who cannot be matched from year to year—“exits”—include both dropouts and those who transfer to other schools. Our administrative database represents the complete universe of students from all five comprehensive high schools in the district as well as students enrolled in a broad variety of alternative programs. This means that local (within the school district) transfers do not pose a problem for matching students from year to year. Nonetheless, the estimate of high school attrition based on the exit rate from the school district database will underestimate the true rate of high school completion.

We address this problem in two ways. First, we attempt to estimate the probable “true” aggregate cohort rate of high school graduation with two indirect methods. The complete details of these exercises are reported in the appendix to this paper, but the key findings are summarized here. The first method assumes that the out-transfer rate is approximately equal to the in-transfer rate, so the difference between the total exit rate and the in-transfer rate (proxy for out-transfers) is the dropout rate. The second method relies on the assumption that the true “out-transfer” rate is equal to the exit rate of students who are at minimal risk of dropping out, such as high school students with a GPA above 3.0. This rate is adjusted for the correlation between GPA and transferring by assuming the correlation between GPA and transferring in high school is comparable to that of students in middle school.

These indirect methods led to similar estimates that the “true” aggregate cohort rate of high school graduation (including transfer students) is between 65 and 70%, assuming that transfer students are as likely to graduate as non-transfer students. Our direct estimates of on-time high school graduation, based on non-transfer students, are that 46% of students graduate within 4 years after entering 9th grade and 50% after six years. The direct estimates are definitely too low, and a more accurate overall rate might be closer to 65-70%, as suggested by our indirect methods. However, the higher aggregate estimates are probably biased upward because the indirect methods assumed that transfer had the same graduation rates as non-transfer students. Because at risk students are considerably more likely to transfer than other students (Lee and Burkam 1992, Rumberger and Larson 1998), the most likely conclusion is that the “true” cohort graduation rate is lower than our indirect estimate of 65-70%.

Even though the overall cohort graduation rate cannot be precisely identified, we can reliably measure patterns of school attrition and the determinants of on-time school graduation. The only necessary assumption is that transfer students share common characteristics with dropouts. Lee and Burkam (1992) report that among high school students in academic trouble, transferring schools is an alternative to dropping out. Rumberger and Larson (1998) note that the determinants of transferring and dropping out are very similar. We argue that our estimates of the determinants of high school enrollment and attrition based on exit rates are probably very close to those that would be obtained from “true” dropout rates.

Variables and Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 presents the summary distributions of background variables for the universe of students for both the descriptive analysis—all first time 9th graders—and the universe of students for the multivariate analysis—first-time 9th graders who were also enrolled in the school district in 8th grade. There are only modest compositional differences between the two samples. In both samples the gender composition is slightly more masculine, and there is considerable ethnic diversity: 57% white, 20% African American, ~15% Asian, and the balance consisting of Hispanics, American Indians, and Pacific Islanders. Family income is represented by a simple measure of poor versus non-poor based on enrollment in subsidized lunch programs. Roughly 42% of students in both samples are from homes with family incomes of less than 185% of the federal poverty level. Enrollment in subsidized lunch programs is a very problematic indicator of family income, but it probably captures a major element of family well-being (Harwell and LeBeau 2010, Hauser 1994).

Table 1.

Percentage Distribution by Background Characteristics and Educational Outcomes of All Students in Four Cohorts of First Time 9th Graders.

| Risk Factors: | First-Time 9th Grade Students |

Also Enrolled in 8th Grade in Same District |

Variable Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| GENDER | Male and Female | ||

| Male | 51.5% | 51.6% | |

| Female | 48.5% | 48.4% | |

|

| |||

| RACE/ETHNICITY | Race/Ethnicity of the student in school records Mutually exclusive categories. |

||

| Hispanic | 5.3% | 4.8% | |

| African American | 19.5% | 20.0% | |

| Asian | 15.2% | 16.1% | |

| American Indian/ Pac. Isl | 2.1% | 1.9% | |

| White | 57.9% | 57.2% | |

|

| |||

| FAMILY INCOME | Eligible for free or reduced lunch program when the student began 9th grade for the 1st time. |

||

| Above 185% of the federal poverty level |

58.3% | 57.6% | |

| Less than or 185% of the federal poverty level |

41.7% | 42.4% | |

|

| |||

| NEIGHBORHOODA | Neighborhood is a set of 38 geographic areas in the school district which correspond to elementary school catchment areas. Students with missing address data (~5%) are classified in an additional dummy variable. Neighborhoods are measured by 38 dummy variables, but the results from only five categories are presented in the multivariate results: the neighborhoods that are closest to values of the 90th, the 75th, the 50th (median), the 25th, and the 10 percentiles of students graduating from high school in four years. |

||

| 90th to 100th Percentile | 14.7% | 9.5% | |

| 75th to 90th Percentile | 12.5% | 14.2% | |

| 50th to 75th Percentile | 24.9% | 29.0% | |

| 25th to 50th Percentile | 20.6% | 20.1% | |

| 10th to 25th Percentile | 15.3% | 15.6% | |

| 0 to 10th Percentile | 12.0% | 11.6% | |

|

| |||

| EVER RETAINED IN GRADES K TO 8TH GRADE |

Students are assumed to have been retained if they were age 16 or older on September 1st of the year in which they start 9th grade for the first time. |

||

| Never Retained | 75.6% | 76.8% | |

| Retained | 24.4% | 23.2% | |

|

| |||

| GPA 2nd SEM OF 8TH GRADEB | Grade point average (GPA) from 8th grade 2nd semester. |

||

| GPA less than 1.0 | 5.6% | 5.6% | |

| GPA 1.0 to 1.99 | 16.6% | 16.6% | |

| GPA 2.0 to 2.99 | 34.7% | 34.7% | |

| GPA 3.0 to 4.0 | 42.5% | 42.5% | |

| Took only Pass/Fail classes | .6% | .6% | |

|

| |||

| Total |

Also Enrolled in

8th Grade in District |

Variable Description | |

|

| |||

| 9TH GRADE CLASSES | Advanced/college bound indicates enrollment in an honors /advanced English class, Full-time special education indicates more than 2/3rds of their classes are special education, Part-time special education indicates less than 2/3rds of their classes are special education, and English as a second language indicates they enrolled in a English as a second language class |

||

| Traditional Curriculum | 69.1% | 68.5% | |

| Advanced/College bound classes | 17.5% | 18.5% | |

| Special education: full time | 3.0% | 3.0% | |

| Special education: part time | 7.7% | 8.0% | |

| English as a second language | 2.7% | 2.1% | |

|

| |||

| GPA 1ST SEM OF 9TH GRADE | First semester of high school GPA on a 0 to 4 scale. |

||

| GPA less than 1.0 | 15.5% | 15.2% | |

| GPA 1.0 to 1.99 | 20.7% | 21.6% | |

| GPA 2.0 to 2.99 | 29.6% | 30.7% | |

| GPA 3.0 to 4.0 | 31.8% | 30.8% | |

| Took only Pass/Fail classes | 2.4% | 1.7% | |

|

| |||

| Sample Size | 8,948 | 7,441 | |

Notes:

Although neighborhoods are measured by 38 dummy variables, the percentage composition is only shown for those between the maximum, minimum and 5 intervening categories: the neighborhoods that are closest to values of the 90th, 75th, 50th, 25th and 10th percentiles of students graduating in 4 years.

8th grade 2nd semester GPA is only reported students enrolled in the district for 8th grade (exclude in-transfers for 9th grade).

The other measure of social background is a classification of “neighborhoods,”—actually a classification of 38 elementary school catchment areas (attendance zones) in the school district. Although neighborhood is indexed by 37 dummy variables in the actual multivariate models, we summarize the classification in the tables with five data points—the 90th, the 75th, the 50th (median), the 25th, and the 10th percentiles of neighborhoods, ranked by proportion of students graduating from high school from the neighborhood.

The next set of variables measure academic standing or achievement prior to (or shortly after) entering high school. An index of prior school retention (during primary or middle school) is based on age at least one year above the modal age for 9th grade. Based on this assumption, almost one-quarter of first-time 9th graders had been retained prior to entry into high school. We also have several measures of placement in selected 9th grade classes that are crude proxies for tracking (presumably based on middle school teacher recommendations and academic performance). About 18% of students were placed in honors or advanced English classes. About one in ten students was identified as partially or solely special education students. These figures correspond very closely to national data which show that about 12% of public school students have an individualized educational plan (IEP) and are eligible for special education services (Ingles and Quinn 1996: 2). About 2 % of students are enrolled in ESL (English as second language) classes3, but most will eventually transition to one of the other streams. The balance of the students in both samples—about 70%— is considered to be in traditional curriculum: not in advanced English, not in ESL, and not in special education.

Two measures of early academic performance are included: 8th grade GPA and 9th grade GPA. The addition of 9th grade GPA as an independent variable, when 8th grade GPA is already included as a covariate, is a proxy for “unpredicted” changes in academic performance when entering high school. Students entering high schools are expected to adjust to a more demanding and bureaucratic educational environment, while simultaneously being allowed more autonomy. The problems of adjustment are partially captured by poorer grades received by many first semester 9th graders, labeled here as the “9th grade shock.” About 1 in 6 entering 9th graders (~15%) has a GPA of less than 1.0, and another 21% have a GPA between 1.0 and 2.0. Altogether, more than one-third of 9th graders begin their second semester of high school with a GPA below 2.0, which indicates failing (or almost failing) one or more classes.

One of the advantages of using administrative records is that missing data are very modest; no more than 4% of the values on any independent variable are missing. As the data appear to be missing at random, we used single imputation regression methods to impute missing values for the explanatory variables. This method does not adjust for uncertainty in the imputed value, but samples from the error distributions to maintain the natural variance of each variable and provides a predicted value for the missing data point. (Allison 2002). We have compared the results here to those from other methods of accounting for missing data and there are virtually no differences.

Description of High School Progress and Graduation

Figure 3 presents an overview of student enrollment and graduation for the four cohorts of students who entered 9th grade (for the first time) from 1996 to 1999. The first column simply shows the universe of students initially enrolled in the fall of their freshman year. By spring of the first year, only 93% of the initial cohort was still enrolled. Not all of the 7% “exits” are dropouts because out-of-district transfers are conflated with student attrition. However, the estimate of 93% of entering 9th graders as still enrolled in the spring of their first year in high school could be upwardly biased because official enrollment records often include students who have stopped attending school regularly. Our point is not to defend any particular figure as “true,” but to describe the broad patterns of student enrollment and exits from year to year.

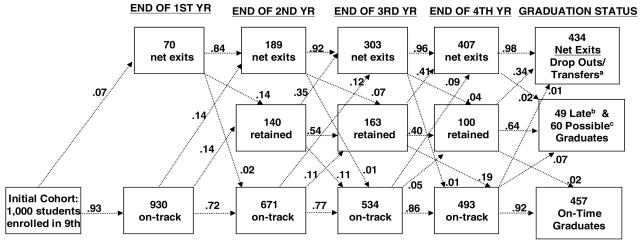

Figure 3.

The Temporal Process of High School Careers and Graduation: Annual Enrollment in Modal and Below Modal Grades for 6 Years After Entering 9th Grade

Overall, there is a net exit rate of about 10 percentage points during each subsequent year of high school: 81% of the baseline sample is enrolled in the spring of the following year, 70% one year later, and only 59% of the original cohort remains enrolled in what should be the senior year. This very rapid attrition does not represent the full extent of student failure. In any given year, 10 to 16 percent of the original entering 9th grade class is enrolled at a grade level below what would be expected by normal progression. The percentage of the original cohort that is enrolled and on-track is only 67%, 54%, and 49% for the second, third, and fourth years in high school, respectively. The final column contains several estimates of high school graduation. Not all students enrolled as seniors in the fourth year will graduate. Some on-track enrolled seniors do not earn enough credits to graduate, while some students who were retained manage to catch up and graduate on time. School records show that almost 46% of the original 9th grade class graduates on time—in 4 years. This graduation rate rises to 51% if the time period is extended to 6 years. Another 6% of the original cohort of 9th graders may eventually receive a high school diploma—they are still enrolled 6 years later and/or have sufficient credits to graduate.

In spite of the limitations of school record keeping and the inability to track out-of-district transfers, the administrative records presented here show a dramatically different picture of high school success than the conventional picture of an almost 90% high school completion rate. The on-time graduation rate of 50% reported here is admittedly too low, and the true figure might be closer to 65%, as discussed earlier. This would still leave 30 to 35% percent of young adults who receive delayed high school diploma, a high school credential not earned from a high school, or who do not have any high school credential.

A Life Table Model of High School Progression and Attrition

Figure 4 shows a more detailed year to year account of the myriad of pathways through high school using the prism of the demographic model of the life table (Chiang 1983, Willett and Singer 1991, Bowers 2010). Specifically, Figure 4 presents conditional probabilities of annual mobility, including progression to the next grade, retention at the same grade level, and exit from the population of enrolled students. These estimates are based on the linked records of three cohorts4 of first time 9th graders that entered high school from 1996 to 1998 in our West Coast metropolitan school district. The life-table model traces the “survival” (remaining enrolled, either on-track or retained) of entering 9th graders for up to six years of high school (measured as of the spring semester of each academic year). The numbers in each box show the proportion of the original population (standardized on a base of 1000) in that status (akin to l(x) values from a life table). The values beside each arrow are the proportion of students in the origin category (conditional probability) who follow a particular trajectory—akin to p(x) and q(x) values in a life table.

Figure 4.

Cohort Probabilities of High School Progression, Retention, and Attrition and Annual Student Status for 1,000 Entering Ninth Graders: Averages from 3 Cohorts of Students Entering High School from 1996 to 1998.

a) Net exits include students who dropped out of high school and those who transferred out of the school district.

b) Students who graduate late (5 or 6 years after entering high school).

c) Students who are still enrolled after 6 years and those with sufficient credits to graduate.

We trace the initial cohort of 9th graders for up to six years, measuring their academic enrollment status in the 9th, 10th, 11th, and 12th grades and then show a summary measure of final graduation status. In each year, students may be in three possible states: on-track, retained (enrolled behind expected grade level), and not enrolled (exited the school data base). Since we cannot identify transfer students at the individual level, the non-enrolled students are labeled as “exits,” not dropouts. Some students who have exited (either as dropouts or transfers) occasionally return as enrolled; the figures in the top row of Figure 4 are “net exits” or former students who are currently not enrolled.

Less than half (45.7%) of the students who begin 9th grade graduate “on time” four years later. Another 11% of the students graduated late (5 or 6 years after entering 9th grade) or “probably graduated”—students who are still enrolled after 6 years and/or had sufficient credits to graduate.

Student retention and exits are evident at every stage of the schooling process. Looking at the bottom panel of “on-track” progression, there is a loss of 28% from the spring of freshman year to the spring of the sophomore year, another 23% from sophomore to junior status, and finally a 14% loss from the junior to the senior year. Failure is ubiquitous in this map of year to year progression. Grade retention is often the first step leading to exiting from the school district, but many students leave without first being held back: 7% in the freshman year, 14% between the freshman and sophomore years, 12% between the sophomore and junior years, and another 9% before the senior year. Retention is also common: 14% of freshmen are retained as are 11% of sophomores.

Retained students are very likely to leave school—about one-third or more of retained students are not enrolled the following year (35% of expected 10th graders, 41% of expected 11th graders, and 34% of expected 12th graders). The most common path of retained students is to remain behind their peers. It is also possible, but fairly rare, for retained students to catch up and resume on-track status. Similarly, students who have exited can re-enter the schools, though they are most likely to be behind their expected grade level. A few rare students leave the school system and return to on-time status (about 1%).

If students remain on-track for four years, then the odds are more than 90% that they will graduate in four years. About 51% of the cohort reaches their senior year on time, and 92% of on-time seniors are on-time graduates. About one-quarter of students in each cohort will experience grade retention sometime during their high school career, and less than half of these students make it to their senior year. About two-thirds of the ever-retained students who make it to their senior year eventually graduate from high school. Of the 40 plus percent of students who exit the school system, only a small fraction returns to graduate from a local school.

The life table values in Figure 4 can be summarized in a variety of ways to show the interdependencies among the various pathways. Table 2 shows the annual exit rates (akin to probabilities of mortality or qx values) by years since entry into high school, conditional on survival (still enrolled) to the prior year in the second column and also by experience of retention in successive columns

Table 2.

Conditional Probability of “Exit” of Enrolled Students by Years Since 9th Grade, 9th Grade Given Survival to that Year for 4 Cohorts of First Time 9th Graders (1996 to 1998)

| Year of First Retention | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| At the End of: |

All Enrolled Students |

Never Retained |

Prior/MS | Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | Year 4 |

| Year 1 | .07 | .06 | .13 | X | X | X | X |

| Year 2 | .14 | .13 | .19 | X | X | X | X |

| Year 3 | .16 | .10 | .23 | .29 | X | X | X |

| Year 4 | .16 | .08 | .21 | .37 | .35 | X | X |

| Year 5 | .11 | .03 | .11 | .29 | .35 | .54 | X |

| Year 6 | .04 | .00 | .04 | .17 | .18 | .31 | .60 |

Note: Students that exited and later returned to school were not included in the estimation of conditional probabilities for the first year that they re-enrolled. Most of these students returned to school at a lower grade level. For this reason, the probabilities in this table vary slightly from those in figure 3.

During the first year of high school, about 7% of enrolled students exit—or disappear from the school database. In each of the next three years, about 14 to 16% of enrolled students exit annually. The risk of “mortality” varies by the enrollment status of student. The third column shows the exit probabilities for “never retained students,” those who are promoted to the next highest grade each year and who entered 9th grade before their 15th birthday. We assume that students who entered 9th grade after their 15th birthday had been retained in primary or middle school. These previously retained students have higher exit rates—generally double those of never retained students.

The balance of Table 2 shows the conditional exit rates for each year (after entering 9th grade) for students retained during high school by the year of their first retention (excluding those retained prior to high school). Since a student is only retained at the end of the year (even if the signs of failure were evident during the year), we can only estimate the impact of retention in the following year. Thus, non-promotion to 10th grade (retention in the 9th grade) can only be measured for students in year 2 after entering 9th grade and the impact on exit can only be measured for the following period—from the 2nd to the 3rd year after entering 9th grade. Even with this limitation, the exit rates of those who are first retained in high school are three or four times those of never retained students (these estimates are consistent with those from longitudinal survey data, see Stearns et al. 2007). Annual exit rates of 30 percent or more for students who fail 9th or 10th grade mean it is very unlikely that such students will ever graduate. The probability of exiting among students still enrolled 5 or 6 years after entering 9th grade and for those who fail their junior or senior years is even higher.

Multivariate Models of On-Time High School Graduation

The descriptive patterns in Figures 3 and 4 and in Table 2 suggest that failure is as common as success in the march toward on-time graduation in high school. What factors might explain these different pathways? The standard sociological model of educational stratification measures the relative effects of social background: socioeconomic status, family structure, race and ethnicity, and other individual-level “risk factors.” Analysts of administrative data generally emphasize the institutional effects of schools and school practices. Here, we blend these traditions by incorporating several indicators of early academic performance into individual-level models of on-time high school graduation.

Table 3 presents two alternative measures of high school graduation—on-time and 6-year graduation rates for two universes of students: all first-time 9th graders and first-time 9th graders who were enrolled in 8th grade in the same school district. Although the universe of students who were enrolled in 8th grade in the same school district is smaller (N = 7,441 compared to 8,948) and a bit more selective (non-transfers are more likely to graduate than the broader universe), the results of all of our analyses are virtually the same. For parsimony, we limit our presentation here to the determinants of on-time graduation for the universe of students who completed 8th graded in the school district.

Table 3.

Percentage of 9th Grade Students who Graduate 4 and 6 Years after Entering High School for All First-Time 9th Graders and for First-Time 9th Graders who were enrolled in 8th Grade in the School District.

| Total | Also Enrolled in 8th Grade in District |

Variable Description | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graduated in 4 Years | 45.7% | 49.8% | Student graduated from high school 4 academic years after beginning high school in this school district. |

| Graduated in 6 Years | 50.6% | 53.0% | Student graduated in six academic years after beginning high school in this school district. (Not available for 1999-00 cohort), |

| Sample Size | 8,948 | 7,441 |

Drawing upon the life course perspective as well as prior research, in Table 4 we model the determination of on-time graduation of first-time 9th graders with a series of logistic regression equations. The dependent variable, high school graduation in four years, conflates out-of-district transfers and dropouts. However, we believe that our estimates of the association between the independent variables and high school graduation are valid as multiple studies have found the correlates of transferring and dropping out to be very similar (Lee and Burkam 1992, Rumberger and Larson 1998).Thus, while the results in the Table 4 analysis are not well suited to predict the “true” levels of high school completion, the associations between the independent variables and the outcome should be relatively unbiased, given the strong correlation between dropping out and out-of-district transfers. The multivariate analyses presented in Table 4 assume that high school graduation is a product of exogenous “risk factors” and intervening school experiences.

Table 4.

Odds-Ratios from Logistic Regressions of Social and Economic Characteristics on Graduating from High School in Four Years (N=7,441) A.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Independent Variables B: | e B | P>∣z∣ | e B | P>∣z∣ | e B | P>∣z∣ | e B | P>∣z∣ |

| GENDER | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Female | 1.41 | .00 | 1.42 | .00 | .97 | .54 | .98 | .74 |

| Male | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| RACE/ETHNICITY | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Hispanic | .58 | .00 | .68 | .00 | .75 | .03 | .84 | .23 |

| African American | .78 | .00 | .99 | .89 | 1.33 | .00 | 1.56 | .00 |

| Asian | 1.27 | .00 | 1.48 | .00 | 1.06 | .49 | .99 | .89 |

| American Indian/Pac Isl. | .54 | .00 | .69 | .05 | .85 | .44 | .95 | .82 |

| White | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| FAMILY INCOME | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Less than 185% of the federal poverty level |

.64 | .00 | .73 | .00 | .75 | .00 | ||

| Greater than 185% of the federal poverty level |

-- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | ||

| NEIGHBORHOOD C | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 90th Percentile | 1.42 | .10 | 1.88 | .01 | 1.40 | .19 | ||

| 75th Percentile | 1.29 | .20 | 1.69 | .02 | 1.19 | .46 | ||

| 50th Percentile (Median) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | ||

| 25th Percentile | .62 | .01 | .84 | .38 | .93 | .74 | ||

| 10th Percentile | .61 | .03 | .62 | .06 | .61 | .08 | ||

| Educational Experiences: | ||||||||

| PRIOR GRADE | ||||||||

| RETENTION | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Retained: 1st to 8th grade | .85 | .02 | .94 | .41 | ||||

| Never Retained | -- | -- | -- | -- | ||||

| 8th GRADE GPA | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| GPA less than 1.0 | .03 | .00 | .15 | .00 | ||||

| GPA 1.0 to 1.99 | .10 | .00 | .34 | .00 | ||||

| GPA 2.0 to 2.99 | .33 | .00 | .64 | .00 | ||||

| GPA 3.0 to 4.0 | -- | -- | -- | -- | ||||

| Took only Pass/Fail classes | .14 | .00 | .35 | .02 | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| 9th GRADE CLASS TYPE | e B | P>∣z∣ | e B | P>∣z∣ | e B | P>∣z∣ | e B | P>∣z∣ |

|

| ||||||||

| College bound classes | 2.04 | .00 | 1.52 | .00 | ||||

| Special education: full time | .41 | .00 | .42 | .00 | ||||

| Special education: part time | .78 | .02 | .90 | .36 | ||||

| ESL Student | .87 | .45 | .72 | .11 | ||||

| Traditional Curriculum | -- | -- | -- | -- | ||||

| 9th GRADE GPA | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| GPA less than 1.0 | .03 | .00 | ||||||

| GPA 1.0 to 1.99 | .15 | .00 | ||||||

| GPA 2.0 to 2.99 | .44 | .00 | ||||||

| GPA 3.0 to 4.0 | -- | -- | ||||||

| Took only Pass/Fail classes | .21 | .00 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Model Indicators: | ||||||||

| McFaddens Pseudo R2 | .03 | .08 | .23 | .31 | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| BIC | 10,121 | 9,914 | 8,488 | 7,730 | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Change in BIC Score D | -- | −207 | −1,426 | −757 | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| −2 Log Likelihood | 9,997 | 9,442 | 7,935 | 7,142 | ||||

|

| ||||||||

| Likelihood Ratio Test p-value D | -- | .000 | .000 | .000 | ||||

Notes:

Although not presented, fixed effects for high school attended 1st semester of 9th grade and cohort fixed were included for all models. Estimates available upon request.

Specific variables definitions are included in table 1.

Neighborhood is a set of 38 geographic areas in the school district which correspond to elementary school catchment areas. Neighborhoods are measured by 38 dummy variables, but only 5 categories are presented here: the neighborhoods that are closest to values of the 90th, 75th, 50th (referent category), 25th and 10th percentiles of students graduating in 4 years.

The change in the BIC score and the p-value from the likelihood ratio test are based upon comparisons of the given model to the preceding model.

The baseline model (Model 1) includes gender and race/ethnicity—two fundamental ascriptive variables. These exogenous risk factors may be explained or mediated through a variety of intermediate variables. In Model 2, we add family income (a dichotomy measuring poverty status) and the neighborhood residence to test the hypothesis that race and ethnic diffe rentials in high school graduation are primarily explained by socioeconomic status and residence. In Model 3, three schooling variables are added as covariates to measure how much inequality in high school graduation is mediated and/or “created” by educational experiences prior to high school. These covariates include a prior school retention (indexed by whether a student is more than one year older than the modal age for 9th grade), 8th grade GPA, and educational placement by type of English class (honors, special education, ESL or regular). Although 9th grade placement is a high school experience, the decision is based on recommendations from 8th grade teachers. Finally, Model 4 adds 9th grade GPA to test the 9th grade shock hypothesis.

Also, to account for between school organizational and procedural variation (e.g. differential grading practices) and temporal variation, fixed effects for the first high school attended in 9th grade and cohort are included in all multivariate regression analyses5. The incremental change in the BIC score for each model (equation) shows the improvement in model fit (above and beyond that of all prior variables) provided by the inclusion of each additional block of variables (Raftery 1995).

Gender has a strong and significant effect that is entirely mediated by early schooling experiences. Girls do better than boys academically, but boys who have similar GPAs as girls are just as likely to complete high school. Gender differences in socialization or maturation mean that girls are probably more likely to pay attention in class, complete assignments, and maintain other behaviors that lead to greater academic success than are boys. Since boys and girls come from the same families and neighborhoods, background variables do not play a difference in explaining gender inequality.

Race and ethnicity are strongly associated with high school graduation. The baseline model in Table 4 shows that Hispanic and American Indian/Pacific Islander students have odds that are less than half white students’ odds of graduating from high school, while African American students have odds that are 25% less than white students’ odds of on-time graduation. Asian Americans have odds that are 20% greater than whites.

The addition of socioeconomic background (income and neighborhood) in Model 2 explains most of the observed black-white disparity in on-time graduation rates and about one third of the gap faced by Hispanic and American Indian/Pacific Islander students. Differential socioeconomic composition, whose influence is only partially measured by these variables, is the primary reason for race/ethnic differentials in high school completion (Hauser, Simmons, and Pager 2004). The observed advantage of Asian American students (relative to whites), however, is increased in Model 2, when socioeconomic and neighborhood characteristics are held constant. This finding indicates that other resources associated with ethnicity (not measured here) can compensate for disadvantaged origins.

The inclusion of early educational experiences in Models 3 and 4 reveals interesting insights into the mechanisms of race/ethnic differentials in high school graduation rates. The higher graduation rates of Asian Americans and lower graduation rates of American Indian/Pacific Islander students are completely mediated by early schooling experiences, especially 8th grade GPA. These patterns do not explain the ultimate reasons for success in schooling, but they do tell us that the reasons for differential high school completion are the same as those that would explain differences in school grades.

An important component of lower graduation rates for Hispanic students is shown in Model 4 which adds 9th grade GPA. This suggests that the transition to high school—“the 9th grade shock” is particularly acute for Hispanic students. An unexpected finding is the net advantage displayed by African American students after adjusting for socioeconomic resources and grades, as this net advantage is most often seen in post-secondary outcomes, not high school completion (e.g. Alexander, Holupka and Pallas 1987, Bennett and Xie 2003, Bennett and Lutz 2009). African American students would be more likely to graduate from high school if they had socioeconomic resources and grades comparable to white students. However, many African American students appear to be able to overcome these obstacles and make it through high school. This finding is consistent with earlier research on the resilience and high educational aspirations of African American adolescents (Bauman 1998).

Measures of family resources, including income and neighborhood, have significant net effects on high school graduation. Net of every measured variable (in Model 4), children from poor families still have odds of graduation that are 25 percent lower than children from non-poor families. Residence also matters. Model 3 shows the students who manage to graduate from high school are clustered in selected neighborhoods—and disadvantaged areas are over-represented among students who drop out. The neighborhood effect is only statistically significant after 8th grade academic performance is held constant in Model 3. Much of the neighborhood impact on high school graduation is independent of 8th grade GPA, but many students from high-risk neighborhoods appear to have unexpected academic problems when entering high school. Model 3 shows that students who were retained in middle or primary school, indexed by being overage relative to grade level, display odds of graduation from high school in four years that are 20 percent lower than students who did not experience a prior retention. The introduction of 9th grade GPA in model 4 shows that the negative impact of a prior retention is reflected in a sudden drop in academic performance in high school.

The addition of the 8th grade GPA and the 9th grade English courses as covariates in model 3 increases the BIC score by 1,426 points (pseudo R-square increases by 15%) relative to model 2, which is a substantial improvement in the model fit (Raftery 1995). Academic ability as well as many other traits that led to academic success is indexed by 8th grade GPA. Students who were placed in honors classes in 9th grade have increased odds of graduating relative to students in regular classes; while students who take special education classes are much less likely to make it through high school in 4 years. Net of background variables and GPA, ESL students are not any more or less likely to graduate from high school than non-ESL students. The extremely positive effect of being placed into an honors class in Model 4 is net of 8th grade GPA. To some extent, tracking may reflect student ability and potential that is reflected in teacher recommendations, but not evident in grades. However, the inclusion of 8th grade GPA is the primary reason for the substantial increase in the model fit statistics.

In Model 4, 9th grade GPA is added as a covariate and shows a very strong impact on on-time high school graduation that is independent of all other measured predictors in this model, including 8th grade GPA. The BIC score increases by 757 points from Model 3 to Model 4. Relative to students with a GPA greater than 3.0, the odds of graduating in four years for students with GPA between 2 and 3 are less than half of the odds of their higher performing peers, while the odds of graduation for students with a GPA between 1.0 and 1.99 are one-seventh the odds displayed by students with a GPA greater than 3.0. Initial grades in high school not only mediate much of the handicaps of the social background and prior school experience, but also have a powerful direct effect on high school graduation.

This finding suggests that the transition to high school (entering 9th grade) is a shock for many students who are not ready for the increased challenges associated with high school, relative to middle schools. Many students who are doing relatively well in 8th grade became 9th grade failures. Among the many background variables that are mediated, in whole or in part, by the 9th grade shock, are minority students, students from poor neighborhoods, and students with prior retentions.

The analysis in Table 4 shows the impact of the 9th grade shock on high school graduation four years later (actually 3 and one half years later). In additional analyses, we find the 9th grade shock has significant negative effects on enrollment at each stage of high school—from 9th grade to 10th grade, from 10th grade to 11th grade, and from 11th grade to 12th grade. Moreover, the impact of the 9th grade shock on student attrition is not entirely mediated by subsequent grades (GPA) for subsequent years. In other words, the 9th grade shock (especially for students who do very poorly in 9th grade) is a significant predictor of attrition for each year of high school even when current GPA is included as a covariate.

Table 5 explores the relationship between 8th and 9th grade GPA in more detail. The first panel is a simple cross-tabulation of 9th grade (first semester) GPA by 8th grade (second semester) GPA for the sample of 7,285 first-time 9th grade students who were enrolled in the same school district for both years. A small number of students with only pass/fail grades are excluded (N=156). The middle panel shows the actual on-time graduation rates (4 years after entering 9th graduate) for students in each cell. The lower panel has the same format as the middle panel, but shows the “net” high school graduation rates, which are predicted by a model in which all other covariates are held constant at their means (all the independent variables in Table 4).

Table 5.

The Impact of 8th and 9th Grade GPA on On-Time High School Graduation

| Panel A. 9th Grade GPA (1st semester) by 8th Grade GPA (2nd Semester) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9th Grade GPA | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| 8th Grade GPA | LT 2.0 | 2.0 to 3.0 | GT 3.0 | Total | Marginal | (N) |

| LT 2.0 | 81% | 16% | 3% | 100% | 23% | 1,667 |

| BTW 2.0 & 3.0 | 46% | 42% | 12% | 100% | 35% | 2,583 |

| GT 3.0 | 10% | 31% | 60% | 100% | 42% | 3,035 |

|

| ||||||

| All Students | 39% | 31% | 30% | 100% | 100% | 7,285 |

|

| ||||||

|

Panel B. Observed On-Time Graduation Rate by 8th and 9th Grade GPA

| ||||||

| 9th Grade GPA | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| 8th Grade GPA | LT 2.0 | 2.0 to 3.0 | GT 3.0 | Total | ||

|

|

||||||

| LT 2.0 | 11% | 33% | 46% | 16% | ||

| BTW 2.0 & 3.0 | 25% | 60% | 68% | 45% | ||

| GT 3.0 | 32% | 66% | 85% | 74% | ||

|

|

||||||

| Total | 19% | 59% | 82% | 51% | ||

|

| ||||||

|

Panel C. Net On-Time Graduation Rate by 8th and 9th Grade GPA

| ||||||

| 9th Grade GPA | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| 8th Grade GPA | LT 2.0 | 2.0 to 3.0 | GT 3.0 | Total | ||

|

|

||||||

| LT 2.0 | 0% | 22% | 54% | 5% | ||

| BTW 2.0 & 3.0 | 5% | 80% | 96% | 48% | ||

| GT 3.0 | 17% | 95% | 99% | 90% | ||

|

|

||||||

| Total | 4% | 79% | 97% | 55% | ||

Notes:

156 students received exlcusively Pass/Fail grades for one or both semesters. They are excluded from the sample.

The observed high school graduation rates are simply the mean in each cell

The net graduation rates are estimated using Table 4 model 4, with background variables held at their mean.

Overall, there is a high correlation between 8th and 9th grade GPA; most low performing students in the 8th grade were still struggling in the 9th grade, and the majority of students who did well in middle school were still above average in high school. However, there was much more downward mobility in average academic performance–about one-third of all students–than there was upward mobility of grades—students whose grades improved in high school relative to middle school. The marginal distributions of the first panel show that the proportion of students with a 3.0 or higher decreased from 42% to 30% and the share with a GPA less than 2.0 nearly doubled from 23 to 39%. Almost half (46%) of students who had an 8th grade GPA between 2 and 3 slipped below 2.0 the following year. Even 4 of 10 students with an 8th grade GPA above 3 saw their GPA drop—31% to the next rung down (between 2 and 3), and 10% dropped below a 2.0 after entering high school.

The middle panel shows the observed levels of on-time high school graduation for the two-way cross-classification of 8th and 9th grade GPA. Overall, there is a strong gradient between GPA (in both years) and the likelihood of on-time graduation. For the majority of students whose grades held steady, there is strong evidence of the impact of academic performance on graduation that is not too surprising. What is more noteworthy is that the dramatic decline in average GPA on entering high school—the 9th grade shock—is strongly associated with a lowered probability of on-time high school graduation. Recall that almost half of students who had a GPA between 2 and 3 in 8th grade slipped to below 2 in their first term in 9th grade. The likelihood that these students experienced an on-time graduation was only 25% compared to 60% for the students whose grades did not drop. A significant number of above average middle school students (GPA above 3) had marks that were in the 2-3 range and some even dropped below 2 upon entering high school. The downward trajectory in grades strongly predicts a lower likelihood of on-time graduation.

The differences between the middle panel and lower panel cast light on whether the 9th grade shock might have been predicted by other characteristics. For example, some students at high risk—based on their background characteristics might have been very prone to the 9th grade shock. The lower panel shows the direct effect of the 9th grade shock on graduation rates that is uncorrelated with any other measured variables. For students who have a very low GPA—below 2—early in high school, they are unlikely to graduate on-time regardless of their 8th grade GPA or any other characteristic.

Conclusions

According to data from the 2010 Current Population Survey, about 88% to 89% of all adult Americans below the age of 60 had completed high school (U.S Census Bureau 2011). This figure is biased upwards because the CPS sample is limited to the household population, but primarily because most people conflate high school equivalency programs with high school graduation. Although both GED holders and high school graduates have “completed high school,” most GED holders dropped out of a regular high school. The disconnect between completing high school and on-time high school graduation is more than just an issue of statistical measurement. Alternative paths to certification are considered “high school equivalents,” but they do not yield equivalent rewards in the labor market. More importantly, the almost universal rates of high school completion obscure the widespread barriers to the successful completion of high school in American public schools.

The analysis of administrative records provides an alternative to survey-based research on education attainment, and we argue that it offers a clearer picture of actual enrollment patterns of high school students from 9th to 12th grades and on-time graduation rates. Administrative records on student enrollment and graduation are not a panacea, indeed there are many limitations and problems with research using administrative data. The most obvious is that unit-record enrollment data are rarely comprehensive (or representative) of the universe of all high schools or all high school students in the United States.

Our analysis is based on a single school district with five comprehensive high schools and a variety of alternative programs in a West Coast metropolitan area. The student population might be described as one of considerable diversity with about 58% white, 20% black, 16% Asian, 5% Hispanic, and 2% American Indian students (see Table 1). There is also considerable economic hardship in the school district with over 40% of students living in homes that are eligible for the free and reduced lunch program (incomes less than 185% of the poverty line). These circumstan ces probably contribute to higher dropout rates than many suburban school districts, yet the conditions did not rival those of inner city schools in many other large metropolitan areas. We do not claim that the estimates of high school attrition reported here are generalizable to the country as a whole; however we suggest that the processes reported here represent common patterns in many American high schools. The major advantage of these data was that we were able to track the complete universe of students from first enrollment in 9th grade for 6 years—until they exited or graduated. Since there were only variations in enrollment, attrition, and graduation patterns across years, we aggregated the record from multiple cohorts (of students entering 9th grade) to obtain a large sample of ~7,500 to 9,000 students (the Ns vary for different analyses)