Abstract

We report the first case of Kytococcus schroeteri implant-related septic arthritis and osteomyelitis, identified by phenotypic tests and 16S rRNA sequencing, which responded to implant removal and doxycycline. 16S rRNA sequencing was useful for the accurate and rapid identification of the organism as it exhibited three different colonial morphologies in vitro.

Keywords: Kytococcus schroeteri, Arthritis, Osteomyelitis, Implant, Infection

Introduction

The genus Kytococcus, literally meaning “a coccus from skin”, was separated from Micrococcus spp. in 1995 based on phylogenetic and chemotaxonomic properties [1]. Kytococci are Gram-positive, pigmented, non-encapsulated, non-motile, aerobic, catalase-positive cocci in pairs or tetrads. The genus now consists of three species: K. sedentarius, K. schroeteri, and K. aerolatus. Sporadic cases of prosthetic valve endocarditis and pneumonia in immunocompromised patients due to K. schroeteri have been described, but to the best of our knowledge, we report here the first case of chronic implant-related septic arthritis with contiguous osteomyelitis caused by a strain of K. schroeteri which exhibited three different colonial morphologies in vitro.

Case report

A 45-year-old Chinese man who suffered from left shoulder dislocation requiring tendon reconstruction with a silicone graft 15 years previously presented with recurrent flare-ups of chronic left shoulder infection manifesting as increasing pain and discharge. He first experienced left shoulder pain and discharge 6 years earlier, at which time a firm subcutaneous mass at the left acromioclavicular joint and a discharging sinus at the coracoid process of the left scapula were detected on physical examination. The roentgenogram showed an old fracture with callus formation at the distal left clavicle. Ultrasonography of the left shoulder showed an inflammatory mass measuring 46 × 9 × 20 mm in the subcutaneous tissues overlying the acromioclavicular joint. This mass communicated with a second mass overlying the coracoid process, the lateral aspect of the pectoralis muscle, and extended to the glenohumeral joint. A sinogram detected a sinus tract, approximately 7 cm in length, which extended superomedially, with its cephalic end located just below the coracoid process of the left scapula. Culture of the debrided wound tissue yielded methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus, and the patient was treated with a 2-week course of cloxacillin. However, his symptoms recurred 1 year later. Computerized tomography scan of the left shoulder showed diffuse bony sclerosis and pus in the sinus tract extending from the skin surface to the old fracture site at the distal left clavicle and left acromioclavicular joint. Repeated debridement was performed, and culture of the debrided tissue yielded “Micrococcus spp.” Despite initial response, the patient’s condition worsened again after another 2 years. Magnetic resonance imaging showed both an enhancing lesion in the left distal clavicle extending into the overlying subcutaneous fat and a non-enhancing mass, suspected to be surgical material, within the lesion. In view of the recurrent symptoms despite repeated wound debridement and cloxacillin, a more extensive operation consisting of ostectomy, joint lavage, wound debridement, and removal of the implanted silicone graft, was performed.

Aerobic culture of the debrided bone yielded tiny non-hemolytic colonies of Gram-positive cocci in tetrads and clusters on 5% sheep blood agar after 24 h of incubation in 5% CO2 at 37°C. After 48–72 h of incubation, colonies with three different types of morphologies became apparent on macroscopic observation (Fig. 1). Morphotype 1 was muddy yellow, dry, rough, and volcano-like, had irregular edges, and measured about 2.5 mm in diameter. Morphotype 2 had a lighter yellow color and smooth edges, was pleomorphic, and measured about 0.5–1.5 mm in diameter. Morphotype 3 had a chalky yellow color, was tiny, and measured about 0.5–1 mm in diameter. All three morphotypes tested positive for catalase, arginine dihydrolase, alkaline phosphatase, and pyrazinamidase, and negative for oxidase, lecithinase, β-galactosidase, and urease. They hydrolyzed gelatin and Tween 80, but not esculin. The API Rapid ID 32 Strep (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France) and the BD Phoenix automated microbiology (Becton–Dickinson Diagnostics, Sparks, MD) systems identified all three morphotypes to be “Micrococcus spp.” with 99% confidence levels. Scanning electron microscopy, performed as described in our previous publications [2, 3], showed spherical cells measuring around 1.0 μm in tetrads or clusters.

Fig. 1.

Appearances of Kytococcus schroeteri morphotypes 1, 2, and 3 in 5% sheep blood agar after 72 h of incubation in 5% CO2 at 37°C. a, b Morphotype 1, c, d morphotype 2, e, f morphotype 3

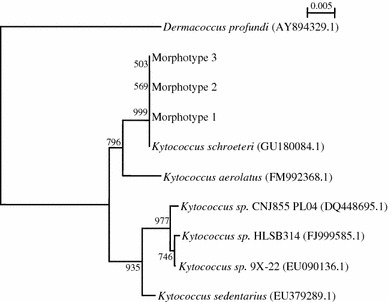

In view of their phenotypic differences from micrococci, namely, resistance to penicillin and oxacillin, and positive arginine dihydrolase activity, 16S rRNA gene sequencing was performed, as described in our previous publications for other Gram-positive cocci [4–6], using LPW1282 5′-GCGTGCTTAACACATGCAAG-3′ and LPW58 5′-AGGCCCGGGAACGTATTCAC-3′ (Sigma-Proligo, Singapore) as the PCR and sequencing primers. The sequences of the PCR products were compared with sequences of closely related species in the GenBank by multiple sequence alignment using ClustalX 1.83 [7], and phylogenetic relationships were determined using the neighbor-joining method. Sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene of the morphotypes showed that the 16S rRNA gene sequences of the three morphotypes were identical. There was no base difference between the 16S rRNA gene sequence of the three morphotypes and that of K. schroeteri (GenBank Accession No. GU180084.1), 12 (1.3%) base differences between the 16S rRNA gene sequence of the morphotypes and that of K. aerolatus (GenBank Accession No. FM992368.1), and 15 (1.6%) base differences between the 16S rRNA gene sequence of the morphotypes and that of K. sedentarius (GenBank Accession No. EU379289.1), confirming that all three morphotypes were K. schroeteri (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic tree showing the relationships of the three morphotypes to closely related species. The tree was inferred from 16S rRNA gene sequence data by the neighbor-joining method and rooted using the 16S rRNA gene sequence of Dermacoccus profundi (AY894329.1). Bootstrap values were calculated from 1,000 trees. The scale bar indicates the estimated number of substitutions per 200 bases. Names and accession numbers are given as cited in the GenBank database

Antimicrobial susceptibility tests were performed by the disk diffusion method (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) on Mueller–Hinton agar. The results were expressed as susceptible, intermediate, or resistant according to the criteria of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) for staphylococci [8]. All three morphotypes were resistant to penicillin, oxacillin, cefuroxime, clindamycin, and fusidic acid and were susceptible to amoxicillin/clavulanate, minocycline, rifampicin, and vancomycin.

Postoperatively, the patient was treated with a 6-week course of oral doxycycline 100 mg every 12 h. He had good clinical response, and the symptoms and raised inflammatory markers resolved after 1 week. He had remained well at the follow-up 3 years after the operation.

Discussion

Traditionally, the different colonial appearances among the three Kytococcus spp. is considered to be a direct and helpful property by which to differentiate them. Whilst K. sedentarius is classically described as having a “deep buttercup yellow” or “cream-white” color [1], K. schroeteri is known for its “muddy yellow” pigmentation [9]. K. aerolatus, which has yet to be implicated in human infection, has a beige pigmentation [10]. Our case describes a novel and important laboratory observation of K. schroeteri: the existence of different colonial morphologies within the same organism. As shown in Fig. 1, colonies with three different macroscopic morphologies were isolated from our patient. In this situation, the macroscopic appearance of the colonies was not reliable tool to differentiate the organisms from other pigmented Kytococcus spp. Although various physiological properties and fatty acid compositions may be useful to separate the three species of Kytococcus, the results are often inconclusive and the analyses time-consuming. In contrast, the application of 16S rRNA gene sequencing allows rapid and accurate identification of the organisms. Using this technique, we identified all three morphotypes from our patient as K. schroeteri. Taking into account their similar scanning electron microscopic appearances, biochemical properties, and identical 16S rRNA gene sequences, we concluded that all three morphotypes belonged to the same strain of K. schroeteri and that this strain possessed different colonial morphologies.

In addition to generating new observations on the organism’s microbiological characteristics, our case also carries significant clinical impact in being the first case of K. schroeteri chronic implant-related septic arthritis with contiguous osteomyelitis. After its first isolation from the blood of a patient with prosthetic valve endocarditis in 2002 [9, 11], the clinical significance of K. schroeteri has been increasingly recognized in the past decade. Including our case, a total of 14 cases of K. schroeteri-related infections have been reported in the literature (Table 1), namely, six (43%) cases of prosthetic valve endocarditis [9, 11–16], five (36%) cases of pneumonia [17–20], one (7%) case of ventriculoperitoneal shunt infection [21], one case (7%) of folliculitis [19], one case (7%) of infective spondylodiscitis [22], and our case of chronic implant-related septic arthritis with contiguous osteomyelitis. The most common site of isolation of the organism was the blood (9/14; 64%), followed by respiratory tract secretions (5/14; 36%), bone (2/14; 14%), prosthetic heart valve (1/14; 7%), and cerebrospinal fluid (1/14; 7%). Among the patients who did not have an infection of a prosthesis, the majority (5/6; 83%) had an immunocompromised state (use of prednisolone or acute myeloid leukemia). The other patient with lumbar spondylodiscitis developed the infection after an operation which compromised the local immunity [22]. Thus, similar to coagulase-negative staphylococci and micrococci, K. schroeteri is regarded as an opportunistic pathogen which is capable of causing prosthesis-related infections, skin infection, osteomyelitis, and fatal pneumonia in immunocompromised hosts. The prognosis of patients with K. schroeteri-related infections mainly depend on the clinical presentation and immune status of the patient. All five patients with pneumonia were immunocompromised, and the majority of them (4/5; 80%) died within 1 month despite supportive treatment. The nine patients with other forms of clinical manifestations (infection of prostheses or lumbar spondylodiscitis) recovered with antibiotics and surgical removal of prostheses. Unlike coagulase-negative staphylococci and micrococci, however, the natural habitat of K. schroeteri has not been confirmed to be the human skin and mucous membranes. Szczerba and Krzeminski [23] isolated K. sedentarius, but not K. schroeteri, from human skin and mucous membranes. Le Brun [12] and colleagues were also unable to recover K. schroeteri from the skin and mucous membranes of their patient. However, at the time of Szczerba and Krzeminski’s study, K. schroeteri was probably unrecognized. Thus, further sampling should be performed to assess whether K. schroeteri, like K. sedentarius, is part of the skin and mucous membranes flora.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with infections due to Kytococcus schroeteri

| Reference | Sex/age and predisposing factor(s) | Clinical syndrome (presentation) | Site of isolation | Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Becker et al. [9, 11] |

F/34 Aortic dissection with implantation of aortic arch conduit and reimplantation of the supraaortic arteries 10 weeks previously |

Prosthetic valve endocarditis (fever, TOE showed paravalvular abscess and vegetation, septic emoblic stroke with right-sided hemiparesis) | Blood | Antibiotics (IV vancomycin, gentamicin and rifampicin for 3 weeks) followed by aortic arch prosthesis replacement | Discharged after admission |

| Le Brun et al. [12] |

M/73 years AVR 3 years previously |

Prosthetic valve endocarditis (fever, exertional dyspnea, TOE showed small vegetations on the aortic bioprosthesis and perivalvular abscess) | Blood, vegetation, perivalvular abscess, and prosthetic valve | AVR and antibiotics (IV vancomycin and then teicoplanin for 6 weeks, gentamicin and rifampicin for the initial 3 weeks) | Discharged after clinical remission |

| Mohammedi et al. [17] |

F/71 years Asthma on prednisone 20 mg daily Hypertension |

Bacteremic community-acquired pneumonia (fever, respiratory distress with right lower lobar pneumonia) | Blood and BAL fluid | Supportive treatment (bronchodilators, steroid, magnesium sulfate and antibiotics including IV ceftriaxone and ofloxacin) | Died 4 days after admission to ICU due to refractory septic shock and multiorgan failure |

| Mnif et al. [13] |

F/49 years MVR 10 years previously |

Prosthetic valve endocarditis (fever, TOE showed prosthesis disinsertion and vegetations on the mitral valve prosthesis) | Blood | MVR and antibiotics (IV pristinamycin, vancomycin and gentamicin for 6 weeks then oral rifampicin and pristinamycin for 3 weeks) | Discharged after clinical remission (6 weeks after admission) |

| Renvoise et al. [14] |

M/70 AVR |

Prosthetic valve endocarditis (fever, TOE showed vegetation on the prosthetic aortic valve and intertrigonal abscess, septic embolic stroke and bilateral renal emboli) | Blood | Antibiotics (IV amoxicillin for 6 weeks and gentamicin for the initial 2 weeks) followed by AVR 3 months afterwards | Discharged after clinical remission |

| Aepinus et al. [15] |

F/38 AVR twice Ventricular septal defect with surgical closure Diabetes mellitus |

Prosthetic valve endocarditis (fever, TOE showed vegetation on the prosthetic aortic valve) | Blood | Antibiotics (IV vancomycin and rifampicin for 6 weeks, gentamicin for the initial 2 weeks; followed by oral levofloxacin and rifampicin for 2 months) | Discharged after clinical remission |

| Jourdain et al. [21] |

M/13 months Cyanotic congenital heart disease Hydrocephalus with VP shunt 5 months previously |

VP shunt infection (fever, acute otitis media, abnormal CSF findings) | CSF | Removal of shunt and antibiotics (IV vancomycin and rifampicin for 27 days) | Discharged after clinical remission |

| Poyet et al. [16] |

M/72 AVR for aortic regurgitation Triple bypass for ischemic heart disease |

Prosthetic valve endocarditis (fever, septic embolic stroke, TTE showed vegetation on the prosthetic aortic valve) |

Blood | Antibiotics (IV vancomycin and rifampicin for 6 weeks, gentamicin for the initial 2 weeks) | Discharged after clinical remission |

| Jacquier et al. [22] |

F/50 L3/4 discectomy for sciatica 8 months previously Diabetes mellitus |

Postoperative lumbar spondylodiscitis (fever and suprapubic pain for 1 day) | Biopsied bone | Antibiotics (IV ofloxacin and rifampicin for 2 weeks followed by oral therapy for 4 weeks) | Discharged after clinical remission |

| Hodiamont et al. [18] |

M/40 Acute myeloid leukemia |

Neutropenic fever with nosocomial pneumonia (neutropenic fever and right upper lobar pneumonia on day 19 after induction chemotherapy) | Blood, sputum and BAL fluid | Supportive treatment and antibiotics (IV ceftazidime, vancomycin, gentamicin and rifampicin) | Died on day 26 of admission due to multiorgan failure |

|

M/52 Acute myeloid leukemia |

Neutropenic fever with nosocomial pneumonia (neutropenic fever and multilobar pneumonia on day 16 after induction chemotherapy) | Blood and BAL fluid | Supportive treatment and antibiotics (IV ceftazidime, vancomycin and rifampicin) | Died on day 27 of admission due to multiorgan failure | |

| Nagler et al. [19] |

M/68 Acute myeloid leukemia |

Neutropenic fever with folliculitis and nosocomial pneumonia (neutropenic fever, scattered crusted papules in the groin and pneumonia on day 12–13 after induction chemotherapy) | Skin biopsy and BAL fluid | Antibiotics (IV cefepime and vancomycin) | Died on day 22 after induction chemotherapy |

| Blennow et al. [20] |

F/43 Acute myeloid leukemia |

Neutropenic fever with bacteremic pneumonia (neutropenic fever, right upper and middle lobar pneumonia 10 days after chemotherapy) | Blood and BAL fluid | Antibiotics (IV piperacillin/tazobactam, vancomycin, linezolid and co-trimoxazole) | Discharged after clinical remission |

| Present case |

M/45 Left shoulder dislocation with tendon reconstruction |

Implant-related septic arthritis and chronic osteomyelitis (recurrent left shoulder wound discharge for 5 years) | Debrided bone and wound tissue | Surgical debridement, removal of prosthesis, and antibiotics (oral doxycycline for 6 weeks) | Discharged after clinical remission |

F Female, M male, MVR mitral valve replacement, AVR aortic valve replacement,TOE transoesophageal echocardiogram, VP ventriculoperitoneal, TTE transthoracic echocardiogram, CSF cerebrospinal fluid, BAL bronchoalveolar lavage, IV intravenous, ICU intensive care unit

In terms of antibiotic susceptibilities, K. schroeteri is frequently resistant to penicillin G (unlike micrococci) and oxacillin [9], a property which is considered to be specific for the genus Kytococcus. This is of clinical importance as these antibiotics are often used as first-line agents in cases of musculoskeletal infections caused by coagulase-negative staphylococci and micrococci. In such cases, empirical antibiotics consisting of ampicillin and cloxacillin are often used. The exact antibiotic susceptibility patterns are frequently omitted unless there is suboptimal clinical response to empirical treatment. As an illustration of this, the chronicity and the extent of disease involvement in our patient would probably have been less if further identification and antibiotic susceptibility tests had been performed on the initially isolated “Micrococcus spp.” to optimize the choice of antibiotics, rather than at the time when the patient suffered from progressive disease despite treatment with cloxacillin. Due to the scarcity of cases, there is no standardized guideline for the optimal choice of antibiotics in K. schroeteri-related infections. Because of the frequent occurrence of prosthesis-related infections in the reported case series, glycopeptides, namely, vancomycin and teicoplanin, in combination with aminoglycosides and rifampicin, were often required in the initial parenteral phase. Oral antibiotics, including fluoroquinolones and tetracyclines, with or without the addition of rifampicin, were used as oral maintenance depending on the individual strains’ susceptibilities, clinical severity, and the presence or absence of prostheses.

In summary, in our case report we describe two important novel findings of K. schroeteri: the existence of variable colonial morphologies and its capability to cause chronic implant-related joint and bone infection. Other clinical entities commonly associated with K. schroeteri include prosthetic valve endocarditis and fatal pneumonia in immunocompromised patients. Therefore, in patients who have prosthesis or are immunocompromised, further analysis to identify this potentially pathogenic organism using 16S rRNA gene sequencing should be performed after initial isolation of coagulase-negative staphylococci or micrococci in the laboratory. Treatment consisting of appropriate antibiotics and removal of infected prostheses is often necessary to prevent significant morbidities and mortalities.

Nucleotide sequence accession number

The 16S rRNA gene sequences of the morphotypes have been lodged within the GenBank sequence database under Accession Numbers JF514888-JF514890.

Acknowledgments

This work is partly supported by the University Development Fund and the Committee for Research and Conference Grant, The University of Hong Kong.

Conflict of interest

None.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

References

- 1.Stackebrandt E, Koch C, Gvozdiak O, Schumann P. Taxonomic dissection of the genus Micrococcus: Kocuria gen. nov., Nesterenkonia gen. nov., Kytococcus gen. nov., Dermacoccus gen. nov., and Micrococcus Cohn 1872 gen. emend. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1995;45:682–92. Erratum in: Int J Syst Bacteriol 46:366 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Woo PC, Tam DM, Leung KW, Lau SK, Teng JL, Wong MK, Yuen KY. Streptococcus sinensis sp. nov., a novel Streptococcus species isolated from a patient with infective endocarditis. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:805–810. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.3.805-810.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woo PC, Tse H, Lau SK, Leung KW, Woo GK, Wong MK, Yuen KY. Alkanindiges hongkongensis sp. nov. A novel Alkanindiges species isolated from a patient with parotid abscess. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2005;28:316–322. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woo PC, Fung AM, Lau SK, Wong SS, Yuen KY. Group G beta-hemolytic streptococcal bacteremia characterized by 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:3147–3155. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.9.3147-3155.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woo PC, Tam DM, Lau SK, Fung AM, Yuen KY. Enterococcus cecorum empyema thoracis successfully treated with cefotaxime. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:919–922. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.2.919-922.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woo PC, Tse H, Wong SS, Tse CW, Fung AM, Tam DM, Lau SK, Yuen KY. Life-threatening invasive Helcococcus kunzii infections in intravenous drug users and ermA-mediated erythromycin resistance. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:6205–6208. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.12.6205-6208.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; twenty-first informational supplement. CLSI Document M100-S21, vol 31 (ISBN 1-56238-742-1). CLSI, Wayne; 2010

- 9.Becker K, Schumann P, Wüllenweber J, Schulte M, Weil HP, Stackebrandt E, Peters G, von Eiff C. Kytococcus schroeteri sp. nov., a novel Gram-positive actinobacterium isolated from a human clinical source. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2002;52:1609–1614. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kämpfer P, Martin K, Schäfer J, Schumann P. Kytococcus aerolatus sp. nov., isolated from indoor air in a room colonized with moulds. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2009;32:301–305. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Becker K, Wüllenweber J, Odenthal HJ, Moeller M, Shumann P, Peters G, von Eiff C. Prosthetic valve endocarditis due to Kytococcus schroeteri. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:1493–1495. doi: 10.3201/eid0911.020683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Le Brun C, Bouet J, Gautier P, Avril JL, Gaillot O. Kytococcus schroeteri endocarditis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:179–180. doi: 10.3201/eid1101.040761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mnif B, Boujelbène I, Mahjoubi F, Gdoura R, Trabelsi I, Moalla S, Frikha I, Kammoun S, Hammami A. Endocarditis due to Kytococcus schroeteri: case report and review of the literature. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:1187–1189. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.3.1187-1189.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Renvoise A, Roux V, Casalta JP, Thuny F, Riberi A. Kytococcus schroeteri, a rare agent of endocarditis. Int J Infect Dis. 2008;12:223–227. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aepinus C, Adolph E, von Eiff C, Podbielski A, Petzsch M. Kytococcus schroeteri: a probably underdiagnosed pathogen involved in prosthetic valve endocarditis. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2008;120:46–49. doi: 10.1007/s00508-007-0903-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poyet R, Martinaud C, Pons F, Brisou P, Carlioz R. Kytococcus schroeteri infectious endocarditis. Med Mal Infect. 2010;40:51–53. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mohammedi I, Berchiche C, Becker K, Belkhouja K, Robert D, von Eiff C, Etienne J. Fatal Kytococcus schroeteri bacteremic pneumonia. J Infect. 2005;51:11–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2004.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hodiamont CJ, Huisman C, Spanjaard L, van Ketel RJ. Kytococcus schroeteri pneumonia in two patients with a hematological malignancy. Infection. 2010;38:138–140. doi: 10.1007/s15010-009-9295-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nagler AR, Wanat KA, Bachman MA, Elder D, Edelstein PH, Schuster MG, Rosenbach M. Fatal Kytococcus schroeteri infection with crusted papules and distinctive histologic plump tetrads. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1119–1121. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2011.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blennow O, Westling K, Fröding I, Ozenci V. Pneumonia and bacteraemia due to Kytococcus schroeteri. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:522–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Jourdain S, Miendje Deyi VY, Musampa K, Wauters G, Denis O, Lepage P, Vergison A. Kytococcus schroeteri infection of a ventriculoperitoneal shunt in a child. Int J Infect Dis. 2009;13:153–155. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacquier H, Allard A, Richette P, Ea HK, Sanson-Le Pors MJ, Berçot B. Postoperative spondylodiscitis due to Kytococcus schroeteri in a diabetic woman. J Med Microbiol. 2010;59:127–129. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.010454-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Szczerba I, Krzeminski Z. Occurrence and number of bacteria from the Micrococcus, Kocuria, Nesterenkonia, Kytococcus and Dermacoccus genera on skin and mucous membranes in humans. Med Dosw Mikrobiol. 2002;55:67–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]