Abstract

Foci of phosphorylated histone H2AX and ATM are the surrogate markers of DNA double strand breaks. We previously reported that the residual foci increased their size after irradiation, which amplifies DNA damage signals. Here, we addressed whether amplification of DNA damage signal is involved in replicative senescence of normal human diploid fibroblasts. Large phosphorylated H2AX foci (>1.5 μm diameter) were specifically detected in presenescent cells. The frequency of cells with large foci was well correlated with that of cells positive for senescence-associated β-galactosidase staining. Hypoxic cell culture condition extended replicative life span of normal human fibroblast, and we found that the formation of large foci delayed in those cells. Our immuno-FISH analysis revealed that large foci partially localized at telomeres in senescent cells. Importantly, large foci of phosphorylated H2AX were always colocalized with phosphorylated ATM foci. Furthermore, Ser15-phosphorylated p53 showed colocalization with the large foci. Since the treatment of senescent cells with phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibitor, wortmannin, suppressed p53 phosphorylation, it is suggested that amplification of DNA damage signaling sustains persistent activation of ATM-p53 pathway, which is essential for replicative senescence.

1. Introduction

It is well known that normal human somatic cells have a finite replicative life span, which resulted from permanent cell cycle arrest caused by persistent activation of DNA damage checkpoint [1]. Therefore, it is presumed that unreparable and sustained DNA damage could be the trigger of replicative senescence. It has been widely accepted that shortened telomeres cause persistent activation of DNA damage checkpoints [2]. Telomeres generally form looped structure, otherwise, the telomeric DNA-ends might be sensed as DNA double-strand break (DSB) [3]. Experimentally, the relationship between telomere dysfunction and replicative senescence has been investigated by using dominant-negative TRF2 proteins. Collapse of telomere loop exposes telomeric DNA-ends, which resulted in senescence induction in normal human fibroblasts [4, 5]. Thus, it is clear that telomere dysfunction is the primary cause of replicative senescence.

As telomere dysfunction activates DNA damage checkpoint factors, DNA damage signaling could be critical for replicative senescence [6]. For example, phosphorylated H2AX foci, which are often referred to as γH2AX foci, have been treated as a surrogate marker for DNA damage signal activation, and the formation of phosphorylated H2AX foci are commonly observed in replicative senescence [7, 8]. In addition, immuno-FISH analysis, which is the combination of immunofluorescent detection of foci and telomere FISH revealed foci formation detected with telomere FISH signals in senescent cells, suggesting telomere in senescent cells causes DSB. Moreover, two genome-wide studies revealed enrichment of H2AX phosphorylation as well as another DNA damage checkpoint factor, 53BP1, at the end of chromosome in senescent normal human fibroblasts [7, 9]. Thus, DNA damage signals triggered by telomere dysfunction appear to be critical for replicative senescence.

It is quite evident that various external stresses causing DNA damage prematurely induce senescence-like features in normal human fibroblasts. For example, ionizing radiation has been reported to induce senescence-like growth arrest (SLGA) [10]. It has been shown that persistent unreparable DSBs result in SLGA, which seems to be equivalent to DSBs located at telomere ends in replicative senescent cells [11]. In fact, we previously found persistent foci in different size in cells inducing SLGA [12]. The initial foci, which were detected immediately after irradiation, were tiny, and most initial foci rapidly disappeared thereafter. In contrast, sustained foci especially for over several days following irradiation are quite large in size, and the large foci are observed in cells underwent SLGA. Because large foci continuously amplify DNA damage signal, prolonged activation of DNA damage checkpoint should play a critical role in irreversible growth arrest. Therefore, we here addressed whether amplification of DNA damage signal is involved in replicative senescence of normal human diploid fibroblasts.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture and Reagent

Normal human diploid fibroblast, HE49, was exponentially grown in Eagle's minimum essential medium (Nissui, Tokyo, Japan) supplemented 10% fetal bovine serum (Thermo Trace Ltd., VIC, Australia). Normoxic cell culture was performed at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 and 95% air, and hypoxic cell culture was performed in a humidified incubator (Ikeda Scientific Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) with 5% CO2, 2% O2, and 93% N2 by supplying nitrogen gas from a nitrogen gas generator (Kojima, Kyoto, Japan). Population doubling level (PDL) was calculated by the following equations

| (1) |

“N” or “N 0” indicate the counted cell number following cell culture or the seeding cell number at the plating. “n” represents population doubling level of each passage.

2.2. Immunofluorescence Staining

Cells grown on coverslips at indicated PDL were washed once with cold PBS−, and then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS− solution for 10 min at room temperature followed by permeabilization with 0.5% Triton X-100/PBS− solution for 5 min on ice. Alternatively, preextraction treatment which excluded chromatin-free nuclear protein was performed by the sequential treatments as follows, permeabilization with 0.5% Triton X-100 in cytoskeleton, CSK, (10 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 7.4, 300 mM Sucrose, 100 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2-6H2O) buffer for 2 min on ice, fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde/CSK buffer for 20 min at room temperature, and then 0.5% NP-40/CSK buffer-treatment for 5 min at room temperature. The primary antibody was treated for 2 h at 37°C with following listed antibodies; mouse monoclonal antiphosphorylated H2AX at Ser139 antibody and rabbit polyclonal antiphosphorylated H2AX at Ser139 antibody (Upstate Biotechnology, NY, USA), rabbit polyclonal antiphosphorylated ATM at Ser1981 antibody (Rockland, PA, USA), mouse monoclonal anti-p53 (Lab Vision, CA, USA), and rabbit polyclonal antiphosphorylated p53 at Ser15 (Cell Signaling Technology, MA, USA). Following the primary antibody treatment, Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat antimouse or rabbit antibody or Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated antimouse or rabbit antibody (Molecular Probes, OR, USA) was treated as secondary antibody for 1 h at 37°C. Nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, 10 ng/mL; Molecular Probes, OR, USA) or propidium iodide, PI. Images were acquired with an Olympus fluorescence microscope and then analyzed with IP Lab software (Scanalytics, VA, USA).

2.3. Immuno-FISH

Immuno-FISH assay was performed as described previously [13]. Briefly, cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained with antiphosphorylated histone H2AX antibody as described above. After immunofluorescence staining step, labeled protein was cross-linked with 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS− for 20 min at room temperature. The samples were then dehydrated in 70%, 90%, and 100% ethanol for 3 min each and air-dried, and DNA was denatured for 30 min on a hotplate at 80°C. After hybridization with a telomere-PNA probe for 5 h, the cells were washed three times with 70% formamide/10 mM Tris, pH 6.8, for 15 min, followed by a 5-min wash with 0.05 M Tris/0.15 M NaCl, pH 7.5/0.05% Tween 20 and a 5-min wash with PBS−. Microscopic analysis was performed as described in the section of immunofluorescence assay.

2.4. Senescence Associated β-Galactosidase Staining

SA-β-gal staining was carried out as described previously [14]. Briefly, cells were plated into 35 mm dish and on the following day, it was fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde containing 0.2% glutaraldehyde for 5 min at room temperature. After fixation, cells were washed extensively with PBS− and were then incubated with stain solution (40 mM citric acid/sodium phosphate, pH 6.0, 5 mM potassium ferrocyanide, 5 mM potassium ferricyanide, 150 mM NaCl, and 2 mM MgCl2) containing 1 mg/mL 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl β-D-galactopyranoside, X-gal, (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd., Osaka, Japan).

2.5. Cell Cycle Analysis

Cells grown on the coverslip were fixed with ice-cold 70% ethanol for 5 min at room temperature. Following extensive wash process with PBS−, samples were treated with PI (50 μg/mL) stain solution containing 200 μg/mL RNase for 30 min at 37°C. Cell cycle analysis was performed using a laser scanning cytometer (LSC-101, Olympus, Tokyo).

2.6. Immunoblotting

Whole cell extracts were prepared in radioimmune precipitation assay buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.2, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, and 0.1% SDS) containing 1x protease inhibitor. The membrane that transferred proteins separated by SDS-PAGE was probed with primary antibody for 2 h at room temperature followed by biotinylated antimouse or -rabbit IgG antibodies (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, UK) as secondary antibody, the bands were visualized using alkaline phosphatase detection system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, UK) by addition of nitroblue tetrazolium/5-bromo-4-chloro-3′-indolyl phosphate (Roche Diagnostic, USA).

3. Result

3.1. Foci Growth of Phosphorylated H2AX in Replicative Senescence

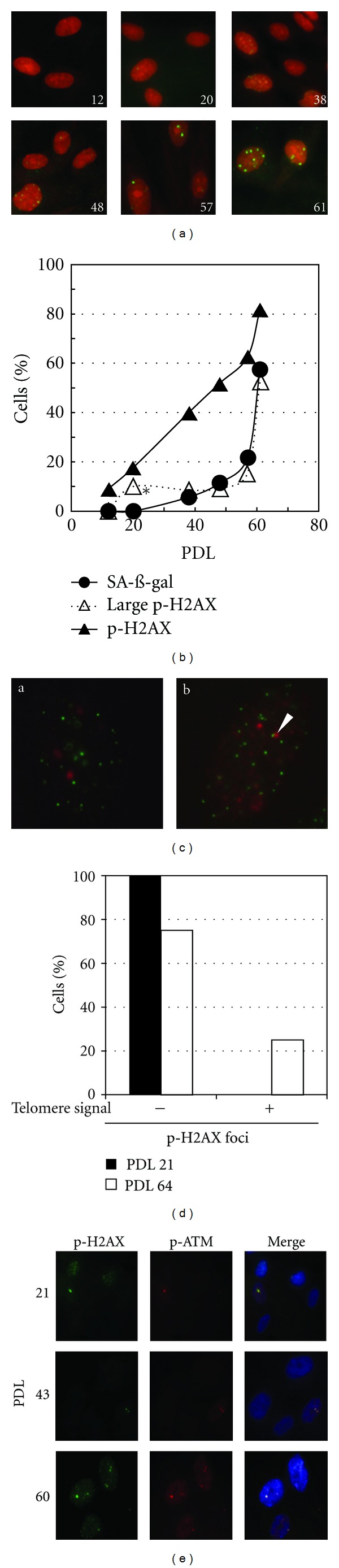

DNA damage signal amplification in replicative senescence of normal human diploid fibroblasts were examined by immunofluorescence staining of phosphorylated histone H2AX at Ser139 at different PDLs (Figure 1(a)). Histone H2AX underwent phosphorylation and formed dotted foci in nearly 10% of cells at PDL12, when cells exponentially proliferated and most cells were negative for SA-β-gal staining (Figures 1(a), 1(b) and 2(a)). The frequency of the cells gradually elevated with increasing PDL, and it reached to nearly 80% at PDL 61, when approximately 60% of cells was positive for SA-β-gal. According to our previous criteria [15], the foci with more than 1.5 μm in diameter were judged as large foci in replicative senescence. No large foci formation was observed at PDL 12. Then, the frequency of large foci positive cell was slightly elevated over the culture days up to PDL 55, and they were formed in nearly 60% of cells at PDL 61. Approximately 65% of positive cells for H2AX phosphorylation showed large foci. The frequency of SA-β-gal positive cells was well correlated with those of the cells with large foci over culture days. These data indicate that large foci formation of DNA damage checkpoint factor correlates well with the induction of replicative senescence.

Figure 1.

Foci growth of phosphorylated H2AX in replicative senescence. (a) Visualization of phosphorylated H2AX foci (green) at the different PDLs indicated by the numbers. Nuclear counterstain was performed with PI (red). (b) Induction frequency of senescent cell (closed circle), H2AX phosphorylation (closed triangle), and large foci formation (open triangle). At least 300 cells and 100 cells were analyzed for senescent induction and foci diameter, respectively. Statistical analysis of the frequency between SA-β-gal (+) and large foci (+) was performed by Welch's test. (*P < 0.01) (c) Each Immuno-FISH image represented a cell with phosphorylated H2AX foci (red) in the absence (a) or the presence (b) of colocalization with telomere FISH signal (green). Arrowhead in (b) represents the phosphorylated H2AX focus accompanied with telomere FISH signal. (d) The frequency of cells in which large foci were detected with (+) or without (−) telomere signal. The data was analyzed with the cells detected large foci in both PDLs of 21 (closed bar) and of 64 (open bar (b)). At least 100 cells were investigated in both PDLs. (e) Colocalization of phosphorylated H2AX (green) and phosphorylated ATM (red) in replicative senescence. Nuclear counterstain was performed with DAPI (blue).

Figure 2.

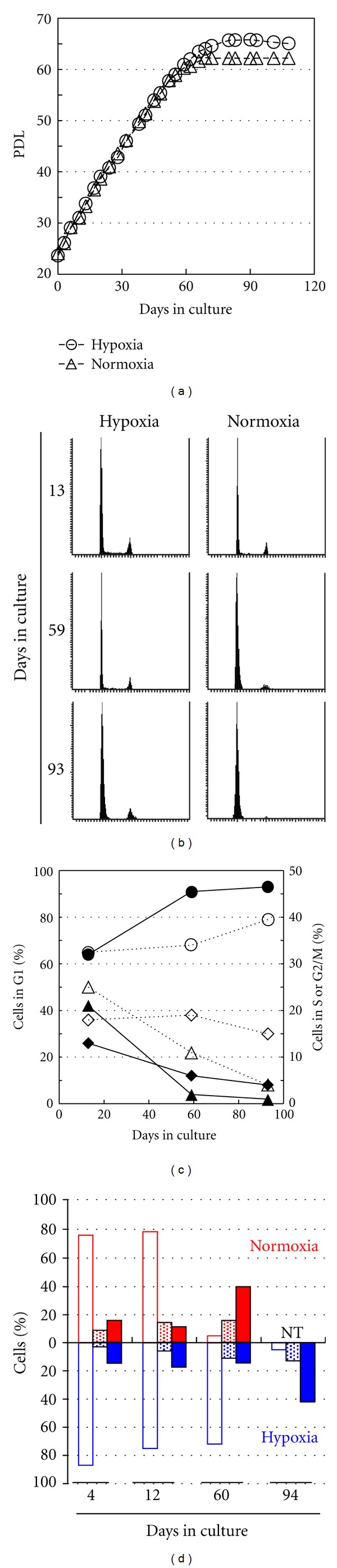

Extension of replicative life span correlated with delayed large foci formation of phosphorylated H2AX. (a) HE49 was cultured under normoxic or hypoxic condition and then PDL was calculated. (b and c) Cell cycle distribution under normoxic (line in c) and hypoxic (dotted line in c) conditions was analyzed by LSC at the indicated time points. Cell cycle data shown in (b) was graphed in (c). The symbols of circle, triangle, and diamond represent the frequency in G1, S, and G2 phase, respectively. The data was obtained from more than 6,000 cells. (d) Phosphorylated histone H2AX status was classified into H2AX phosphorylation negative (open bar), H2AX phosphorylation positive (dotted bar), and large foci formation (closed bar) and the frequency of each status were investigated in replicative senescence under normoxic (red) and hypoxic (blue) condition. NT indicated “not tested.” At least 100 cells were analyzed in each condition.

Localization of large foci was investigated by Immuno-FISH analysis that combined immunofluorescent detection of H2AX phosphorylation with telomere FISH (Figure 1(c)). Whereas large foci did not colocalize with telomere signals at PDL 21, large foci associated with telomere signals were observed in 25% at PDL 61 (Figure 1(d)). It should be mentioned that large foci were completely colocalized with foci of phosphorylated ATM, that is, active form of ATM, at any PDLs (Figure 1(e)). These data indicate that ATM-dependent DNA damage signal is amplified at the site of large foci in senescent cells, indicating that not only dysfunctional telomeres but also interstitial DNA breaks could be associated with senescence induction.

3.2. Extension of Replicative Life Span Delayed Large Foci Formation of Phosphorylated H2AX

The link between senescence induction and large foci formation was further examined in cells cultured under 2% of hypoxic condition which extended replicative life span [16]. The cells used for this study were originally cultured under normoxic condition up to PDL 21 before they were moved to hypoxic culture condition. Then, they were divided into two different culture conditions, hypoxia and normoxia. Therefore, we set day 0 in culture at PDL 21. Both cell groups were individually maintained and subcultured at the same day. PDL of both cells was equally elevated at the initial culture period, however, cell growth was completely stopped under normoxic condition approximately at 65 days, while the cells in hypoxic condition continued proliferation for more than 8 cell division, and finally arrested approximately at 80 days (Figure 2(a)). Cell cycle analysis of S phase demonstrated that growth arrest was much delayed under hypoxic condition (Figures 2(b) and 2(c)). For example, the fractions of S phase, at day 13, were similarly detected under normoxia and hypoxia, respectively. It was markedly diminished to 5% under normoxia, while the fraction still detected in 16% under hypoxia at day 59 and eventually diminished to 4% at day 93. In hypoxic condition, large foci formation was similarly observed as shown in Figure 1, however, they were detected much later compared with the cells cultured in normoxic condition (Figure 2(d)). Therefore, these data demonstrated that large foci were generated by endogenous oxidative stress, and the formation of large foci was strongly correlated with senescence induction.

3.3. Activation of ATM-p53 Pathway at the Large Foci of Phosphorylated H2AX

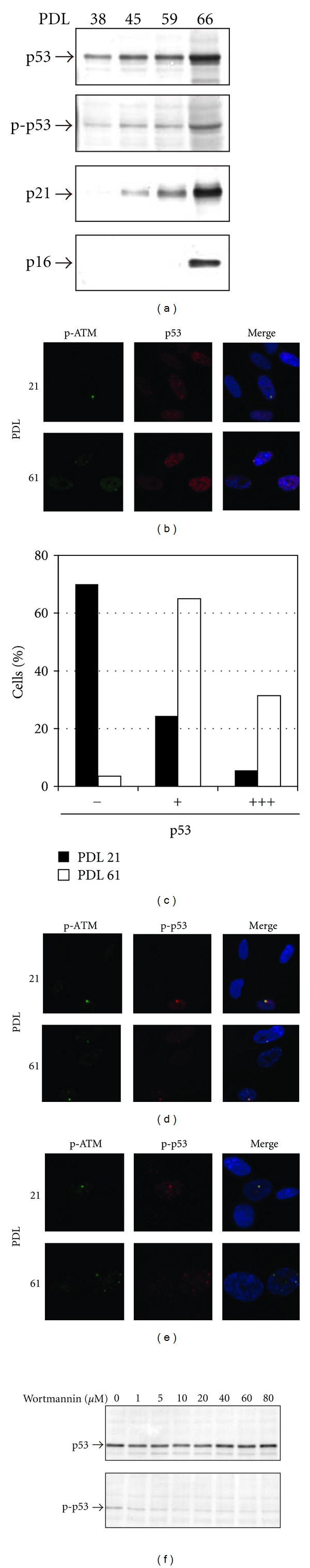

We next examined whether ATM-p53 pathway is involved in persistent activation of cell cycle arrest in senescent cells. In replicative senescence of HE49, accumulation of p53 accompanied with phosphorylation at Ser15 and transactivation of p21 was observed over the culture time. Especially, p53-p21 pathway was persistently upregulated when p16 was also induced (Figure 3(a)). p53 was then visualized by immunofluorescence staining following formalin fixation at indicated PDLs (Figure 3(b)). Approximately 20% of cells at PDL 21 weakly expressed p53 in nuclear (indicated as “+” in Figure 3(c)), and others were under detection level of p53. Increase of p53-expressing cells was observed at PDL 61 as detected in western blotting (Figure 3(a)), and p53 highly accumulated in 30% at PDL 61 (indicated as “+++” in Figure 3(c)). Interestingly, accumulated p53 formed colocalized foci with phosphorylated ATM foci (Figure 3(b)). p53 was also visualized in the cells receiving preextraction treatment followed by formalin fixation (Figure 3(d)). Preextraction removed chromatin-free nuclear protein and accumulating p53 in nuclear disappeared, while aggregated p53 was still detected at the sites formed large foci of phosphorylated ATM. Furthermore, Ser15-phosphorylation form of p53 was also detected at the large foci of phosphorylated ATM following preextraction (Figure 3(e)). Furthermore, the effect of ATM kinase inhibition on p53 phosphorylation at Ser15 in senescent cells revealed suppression of phosphorylation level especially at lower doses (Figure 3(f)), suggesting ATM is involved in p53 activation in replicative senescence. These data indicate ATM-p53 pathway persistently activated at the site of large foci in senescent cells.

Figure 3.

Activation of ATM-p53 pathway at the large foci of phosphorylated H2AX. (a) Investigation of factors relating to G1 checkpoint machinery in replicative senescence was performed by western blotting. “p-p53” indicated Ser15-phosphorylated p53. (b) p53 accumulation in cells formed phosphorylated ATM foci (p-ATM) in replicative senescence. (c) The cells detected different p53 level was scored at both PDL of 21 (closed bar) and of 64 (open bar) (n ≥ 1,000). “−”, “+”, and “+++” indicated p53 negative, positive, and strong positive, respectively. Representative cells of p53 positive or strong positive were shown in upper or lower image in (b). (d and e) The cells were preextracted to remove chromatin-free nuclear protein, and then detected indicated proteins. (f) p53 phosphorylation at Ser15 was examined in senescent cells treated with a series of concentration of wortmannin.

4. Discussion

The present study demonstrates that persistent amplification of DNA damage signal is involved in replicative senescence.

It has been generally thought that prolonged activation of DNA damage response at dysfunctional telomere results in irreversible cell cycle arrest in replicative senescence [17]. Indeed, foci formation at telomeres is detected in senescent cells [7, 8]. Our current study extends such observation and adds the evidence that DNA damage signals at dysfunctional telomeres are mostly amplified.

Our previous findings demonstrate that amplification of DNA damage signal relates to persistent activation of ATM-p53 pathway sufficient for executing irreversible G1 arrest in response to ionizing radiation [11, 12]. We also demonstrated that increase in foci size was essential for amplification of DNA damage signals. In fact, residual foci, which sustain for over several days following irradiation, are larger foci, which are indispensable for proper activation of p53 [15]. The present study clearly demonstrated that formation of large foci also takes place in replicative senescent cells (Figure 1(a)). Our results are the following: (1) increase of cells with large foci is well correlated with the senescence induction (Figure 1(b)), and (2) hypoxic cell culture, which extends replicative life span, delays the formation of large foci (Figure 2), indicate mutual relationship between amplification of DNA damage signals and induction of replicative senescence.

It has been thought that telomere dysfunction results in activation of DNA damage response. Dysfunctional telomere is able to be detected by foci formation of DNA damage checkpoint factors which accompanied with telomere FISH signal, so called telomere-induced foci (TIF) [8, 13], and we also detected TIF in 25% of senescent cells (Figure 1(c)). It is generally thought that TIF represents uncapped telomere exposing telomeric DNA-ends. Therefore, it is assumed that unreparable DSBs causes prolonged activation of DNA damage response [8]. On the other hand, our previous data represent localization of phosphorylated H2AX foci not only at DSB site but also on dicentric chromosome [18, 19]. It has also been demonstrated that telomere-telomere fusion-mediated dicentric chromosomes were formed in senescent normal human fibroblasts of MRC-5 and WI-38 [20, 21], suggesting another possibility that TIF might be reflected the region on dicentric chromosome derived from telomere fusion. Our immuno-FISH analysis indeed demonstrated that large foci without telomere-FISH signal in 75% of senescent cells (Figure 1(c)). Nakamura et al. precisely analyzed foci formation with metaphase chromosome spreads of presenescent WI-38 and BJ normal human fibroblasts [22]. They found localization of foci at the end of chromosome which lacked telomere-FISH signal in more than 50% of foci detected in presenescent metaphase spreads. Therefore, large foci formation without telomere-FISH signal in our telomere-FISH analysis might involve such foci. Alternatively, following telomere-telomere fusion, Fusion-Bridge-Breakage (FBB) cycle might initiate DSBs at interstitial chromatin region [23]. Once dysfunctional telomeres are fused and generate dicentric chromosome, two centromeres are pulled in opposite directions during anaphase. Such a chromosome regionally gets a tension, eventually, DNA break is initiated at interstitial chromatin region of dicentric chromosome. On the basis of the model, dysfunctional telomeres might be in the one mechanism of large foci formation in replicative senescence, but interstitial chromatin region could also be the candidate to serve DNA ends.

Formationoflarge foci activates ATM-p53 pathway, which triggers p21 transactivation. It has been represented that p53-p21 pathway as well as p16 is associated with irreversible growth arrest in senescent cells, especially p16 expression is elevated at late senescent stage [24]. We also confirmed induction of both pathways in replicative senescence (Figure 3(a)). We found that lower concentration of wortmannin treatment in senescent cells significantly suppressed Ser15-phosphorylation of p53 (Figure 3(f)). Previous reports demonstrated that IC50 of wortmannin treatment for ATM was approximately 5 μM [25], and ATM, but not DNA-PK, is known as a major factor for Ser15-phosphorylation of p53 in vivo in response to DSB [26]. Thus, it can be concluded that ATM-dependent p53 activation is amplified at large foci.

In conclusion, our data presented here provide strong correlation between large foci formation of DNA damage checkpoint factors and replicative senescence induction. Large foci could be formed at dysfunctional telomeres as well as at interstitial chromatin regions, which ensures persistent activation of DNA damage response. Thus, persistent amplification of DNA damage signals via ATM-p53 pathway plays a critical role in replicative senescence.

References

- 1.Hayflick L, Moorhead PS. The serial cultivation of human diploid cell strains. Experimental Cell Research. 1961;25(3):585–621. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(61)90192-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sikora E, Arendt T, Bennett M, Narita M. Impact of cellular senescence signature on ageing research. Ageing Research Reviews. 2011;10(1):146–152. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Misri S, Pandita S, Kumar R, Pandita TK. Telomeres, histone code, and DNA damage response. Cytogenetic and Genome Research. 2009;122(3-4):297–307. doi: 10.1159/000167816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smogorzewska A, Karlseder J, Holtgreve-Grez H, Jauch A, De Lange T. DNA ligase IV-dependent NHEJ of deprotected mammalian telomeres in G1 and G2. Current Biology. 2002;12(19):1635–1644. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01179-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karlseder J, Broccoli D, Yumin D, Hardy S, De Lange T. p53- and ATM-dependent apoptosis induced by telomeres lacking TRF2. Science. 1999;283(5406):1321–1325. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5406.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gorbunova V, Seluanov A. Making ends meet in old age: DSB repair and aging. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development. 2005;126(6-7):621–628. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Di Fagagna F, Reaper PM, Clay-Farrace L, et al. A DNA damage checkpoint response in telomere-initiated senescence. Nature. 2003;426(6963):194–198. doi: 10.1038/nature02118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sedelnikova OA, Horikawa I, Zimonjic DB, Popescu NC, Bonner WM, Barrett JC. Senescing human cells and ageing mice accumulate DNA lesions with unrepairable double-strand breaks. Nature Cell Biology. 2004;6(2):168–170. doi: 10.1038/ncb1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meier A, Fiegler H, Mũoz P, et al. Spreading of mammalian DNA-damage response factors studied by ChIP-chip at damaged telomeres. EMBO Journal. 2007;26(11):2707–2718. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suzuki M, Boothman DA. Stress-induced premature senescence (SIPS)-influence of sips on radiotherapy. Journal of Radiation Research. 2008;49(2):105–112. doi: 10.1269/jrr.07081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suzuki K, Mori I, Nakayama Y, Miyakoda M, Kodama S, Watanabe M. Radiation-induced senescence-like growth arrest requires TP53 function but not telomere shortening. Radiation Research. 2001;155(1):248–253. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2001)155[0248:rislga]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suzuki M, Suzuki K, Kodama S, Watanabe M. Interstitial chromatin alteration causes persistent p53 activation involved in the radiation-induced senescence-like growth arrest. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2006;340(1):145–150. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.11.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herbig U, Jobling WA, Chen BPC, Chen DJ, Sedivy JM. Telomere shortening triggers senescence of human cells through a pathway involving ATM, p53, and p21CIP1, but not p16INK4a. Molecular Cell. 2004;14(4):501–513. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00256-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dimri GP, Lee X, Basile G, et al. A biomarker that identifies senescent human cells in culture and in aging skin in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1995;92(20):9363–9367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamauchi M, Oka Y, Yamamoto M, et al. Growth of persistent foci of DNA damage checkpoint factors is essential for amplification of G1 checkpoint signaling. DNA Repair. 2008;7(3):405–417. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kashino G, Kodama S, Nakayama Y, et al. Relief of oxidative stress by ascorbic acid delays cellular senescence of normal human and Werner syndrome fibroblast cells. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2003;35(4):438–443. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00326-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohtani N, Mann DJ, Hara E. Cellular senescence: its role in tumor suppression and aging. Cancer Science. 2009;100(5):792–797. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01123.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suzuki M, Suzuki K, Kodama S, Watanabe M. Phosphorylated histone H2AX foci persist on rejoined mitotic chromosomes in normal human diploid cells exposed to ionizing radiation. Radiation Research. 2006;165(3):269–276. doi: 10.1667/rr3508.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hall EJ. Molecular biology in radiation therapy: the potential impact of recombinant technology on clinical practice. International Journal of Radiation Oncology Biology Physics. 1994;30(5):1019–1028. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(94)90305-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thompson KVA, Holliday R. Chromosome changes during the in vitro ageing of MRC 5 human fibroblasts. Experimental Cell Research. 1975;96(1):1–6. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(75)80029-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benn PA. Specific chromosome aberrations in senescent fibroblast cell lines derived from human embryos. American Journal of Human Genetics. 1976;28(5):465–473. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakamura AJ, Chiang YJ, Hathcock KS, et al. Both telomeric and non-telomeric DNA damage are determinants of mammalian cellular senescence. Epigenetics & Chromatin. 2008;1:p. 6. doi: 10.1186/1756-8935-1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murnane JP. Telomere dysfunction and chromosome instability. Mutation Research. 2012;730(1-2):28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alcorta DA, Xiong Y, Phelps D, Hannon G, Beach D, Barrett JC. Involvement of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p16 (INK4a) in replicative senescence of normal human fibroblasts. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93(24):13742–13747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sarkaria JN, Tibbetts RS, Busby EC, Kennedy AP, Hill DE, Abraham RT. Inhibition of phosphoinositide 3-kinase related kinases by the radiosensitizing agent wortmannin. Cancer Research. 1998;58(19):4375–4382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Araki R, Fukumura R, Fujimori A, et al. Enhanced phosphorylation of p53 serine 18 following DNA damage in DNA- dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit-deficient cells. Cancer Research. 1999;59(15):3543–3546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]