Abstract

The American College of Radiology Imaging Network (ACRIN) is the youngest of the NCI cooperative groups. ACRIN trials are directed towards evaluating the applications of diagnostic imaging and image-guided treatment to cancer. As ACRIN begins its third funding cycle, the organization is increasingly emphasizing several themes: linking imaging surveillance to pre-imaging testing for disease to improve the efficiency of cancer screening; the evaluation of imaging tests as biomarkers for molecular and physiologic processes in cancer; the standardization and validation of imaging tests to predict and monitor response to treatment; improved characterization of the extent and biology of cancer; and the translation of new emerging technologies from first-in-human testing to multi-center trials. ACRIN is poised to pursue its own research agenda, collaborate with other research entities to address key issues in cancer care, and place at the service of the other cooperative groups its electronic infrastructure to improve imaging in therapeutic trials. ACRIN’s pursuit of its unique mission as the sole cooperative group directed principally toward diagnosis has made the network an integral part of the cancer research community.

The Formation of ACRIN

The American College of Radiology Imaging Network (ACRIN) is the youngest of the NCI-funded clinical trials cooperative groups, having been founded in 1999 [1]. It also is the only one of the cooperative groups whose primary mission is focused on diagnostic, rather than therapeutic, medical technologies. The need for such a consortium was made apparent by a number of trends in the 1990s: the growing importance of imaging to cancer care; the increasing employment of imaging as a marker of therapeutic activity in clinical trials; and the recognition that medical imaging could provide a relatively non-invasive representation of phenotypical changes associated with cancer, which could be correlated with the accelerated understanding of oncological genetics.

As a result, in 1997, Dr. Robert Wittes, then of the National Cancer Institute (NCI), convened two informal meetings among physicians, payers, and representatives of industry to discuss how NCI might address its need to better incorporate medical imaging and involve medical imagers in clinical trials. The upshot was a request for applications (RFA) let by NCI in early 1998 that specified the components of the NCI vision for the development of a clinical trials “network.” The network was to be comprised of two linked grants – one for a headquarters, the other for a biostatistical and data management center. The two grantees were to collaborate in developing an effective, nimble, non-member network that would develop, implement, gather data for, and analyze the results of multi-center trials of the most important applications of imaging to cancer – all imaging technologies and all cancers. The winning consortium was to collaborate with the newly formed NCI Diagnostic Imaging Program (now the Cancer Imaging Program (CIP)), led by Dr. Daniel Sullivan, under a U01 mechanism. Several consortia applied in competition, and in the fall of 1998, ACRIN was awarded five year grants for a maximum of $23 million. The initial funding began March 1, 1999.

The terms of the award, as noted above, called for an entirely new kind of organization, one in which participants (individuals and institutions), rather than standing institutional members, would take part in the preparation and conduct of one trial but not necessarily participate in the next. While the several people involved in writing the initial linked grants had a clear vision of what such an organization should eventually become, there was little outside experience to call upon for guidance on how to achieve the goal. With the exception of another young cooperative group, the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group (ACOSOG), which had been formed a little over a year earlier, the other cooperative groups had been functioning for as long as forty years, and they all operated on the basis of institutional memberships.

In addition to forming its organization, ACRIN would have to simultaneously develop its policies and procedures, grow its staff, and initiate the research agenda it had promised to address. ACRIN’s leadership understood that many at NCI viewed ACRIN as a considerable risk, and that the organization would need to have something to show for the investment by the end of the initial funding period.

Organization and Operations

From the start, ACRIN understood that, to be successful it would have to develop an integrated and effective organization in a decentralized and widely disseminated setting. To achieve this, ACRIN makes maximum use of the capabilities afforded by modern electronic communications and the Internet. Importantly, ACRIN was the first major multi-center trials group with nearly all data collection and study management done via the Web. To this end, ACRIN developed a proprietary software program that allows sites to register and randomize (if directed by the protocol) study participants, then transmit and archive their image and non-image data over the Web at any hour, every day of the year. The sites accomplish this activity through a protected portal on the ACRIN Web site (www.acrin.org), which is the principle infrastructure for trial coordination among Headquarters and Data Management Center (The American College of Radiology research office in Philadelphia), the Biostatistics Center (Brown University, Center for Statistical Sciences), and the site investigators and research associates.

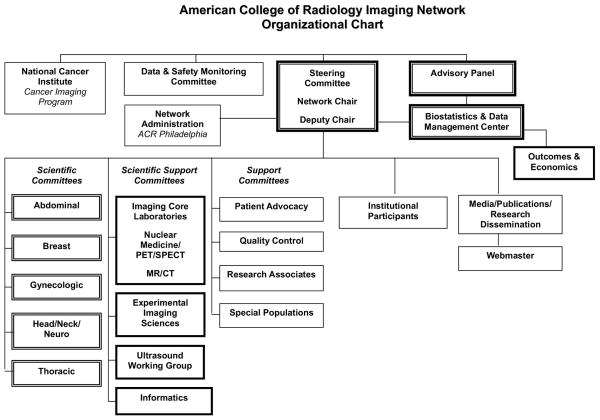

ACRIN’s organization (Figure 1) is led by a Steering Committee, headed by the Network Chair. The makeup of the Steering Committee has changed over the course of its existence – along with the entire organizational structure – as ACRIN leadership has continually sought to improve operations in the context of what it has learned. Currently, the Steering Committee is comprised of all chairs of standing committees, along with representation from the Biostatistical Center and NCI CIP.

Figure 1.

ACRIN organizational structure

ACRIN’s scientific agenda arises from the organ-based scientific committees. Their efforts are complemented by support committees and the functions of Vice Chairs for Institutional Participation and Media and Publications. In the context of ACRIN’s organizational activity, the work of the Institutional Participation Committee is particularly important, since it is this committee that qualifies ACRIN accrual sites both generally and for participation in specific clinical trials. To date, more than 180 academic and community imaging sites have qualified to participate in ACRIN and 114 sites actually have participated in at least one ACRIN trial.

ACRIN has increasingly sought to make involvement in the organization multi-disciplinary. Each scientific committee includes in its membership not only experts in medical imaging but medical, surgical, and radiation oncologists. Each committee has one or more faculty statisticians, a representative of ACRIN data management and an audit staff member, an institutional research associate, and a patient advocate. The participation of a research associate and patient advocate in the committee structure deserves special mention. Prior to ACRIN, few research associates specialized in imaging, so ACRIN had to build this essential resource from the ground up through the development of its Research Associates Committee. Now a vibrant, fully integrated part of ACRIN, the committee assigns representation to all committees and trial teams, conducts educational sessions at ACRIN meetings, and has devised an educational and testing program for research associate advancement conducted electronically via the ACRIN Web site. Similar problems existed with regards to ACRIN’s developing a committed cohort of patient advocates. Most advocates attach themselves to the cause of a specific cancer, based on their personal experiences. This fits poorly with ACRIN’s focus of applying imaging technology to various cancers. Despite this, ACRIN has been successful in developing a highly involved group of advocates as its Patient Advocate Committee, which, like the Research Associates Committee, is involved in the design and conduct of every ACRIN trial. To accomplish this, the committee designed Project IMPACT (Improving Patient Accrual to Clinical Trials), requiring the input of a trial team’s patient advocate in every stage of trial activity. Project IMPACT has become a well publicized model for the involvement of patient advocates in trials and how advocate involvement can improve trial development and accrual.

The Goals of ACRIN

Since the initial response to the 1998 RFA until the present, ACRIN’s “overarching goals” have evolved only in minor ways.

Through clinical trials of diagnostic imaging and image-guided treatment technologies, ACRIN seeks to develop information that will:

Improve the length and quality of lives of cancer patients;

Result in the earlier diagnosis of cancer;

Lead to effective monitoring of patients at risk for cancer.

ACRIN has pursued these goals by addressing its trials to the full spectrum of potential applications of imaging to cancer: screening and early detection; diagnosis and staging; image-guided treatment; and imaging as a marker of response to treatment. ACRIN’s trials to date are listed according to these categories as Table 1 (protocols for each trial are available at www.acrin.org). In selecting studies for its portfolio, ACRIN seeks to serve both the needs of the medical imaging community – addressing the development, evaluation, and improvement of imaging modalities - and the broader interests of the cancer community seeking guidance on how imaging can better direct treatment.

Table 1.

ACRIN trials by imaging application (full protocols available at www.acrin.org)

Screening and Early Detection

|

Diagnosis and Staging

|

Image-Guided Treatment

|

Gauging Response to Treatment

|

Screening and Early Detection

A principal activity of ACRIN has been to investigate how imaging can be directed to improving the early detection of cancer in the belief that finding and treating malignancy at a more formative stage will reduce cancer-related mortality. While that may seem intuitive, there are factors that complicate the verity of that strategy, requiring testing for specific cancers and technologies in clinical trials [2]. ACRIN has conducted a number of trials involving the screening of asymptomatic patients. These trials have tended to require large numbers of subjects, been expensive, and mostly conducted with the assistance of sizable supplements to ACRIN’s core funding.

Diagnosis and Staging

The traditional use of imaging for cancer patients has been to determine whether cancer is present, characterize it as well as possible, and determine its extent. Over the last thirty years a succession of technologies, such as x-ray computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and positron emission tomography (PET) have been employed for this purpose. ACRIN has initiated trials employing these now conventional but still evolving technologies, as well as newer, emerging imaging modalities like magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) and MRI using a novel contrast agent in an effort to better determine the value of imaging for this application.

Image-Guided Treatment

A major evolving role for medical imaging is to direct the placement of percutaneous probes, catheters, and other devices with the capacity to destroy tumors and then to evaluate the extent to which treatment has been technically successful. A recent development is the emergence of tehnologies employing imaging to direct the transcorporeal high energy destruction of tumors without disturbing the skin surface, and ACRIN is in the process of designing a pilot study to evaluate such a technology.

Imaging as a Marker of the Effectiveness of Therapy

Morphologic maging has often been used in therapeutic trials as a trial endpoint indicating whether subjects’ tumor burden is stable, increasing, decreasing, or resolved. For the most part, this has been accomplished by 2-dimensional measurements of tumors portrayed on CT and MRI scans. However, there are some limitations with this approach. Dimensional changes may take months to manifest. There is often poor correlation between morphologic imaging outcomes and true health outcomes. And particularly with new targeted therapeutic agents, tumor activity may change dramatically with treatment but not be reflected in change in tumor size. A host of new imaging technologies providing functional and molecular information on tumors, such as PET, dynamic contrast enhanced- (DCE) MRI, and MRS have emerged as potential functional and molecular markers of cancer activity and are being standardized and tested in ACRIN trials. A specific function of the new ACRIN Experimental Imaging Sciences Committee is to evaluate newly emerging techniques in support of this approach.

Methodologic Perspective

As noted above, ACRIN studies address a broad spectrum of questions related to imaging. Additionally, responding to the rapid speed of evolution of imaging technology, the network evaluates both emerging and established modalities and formulates study designs and evaluation criteria that are appropriate for each phase of development of imaging technology. Responding to the growing need for information on the role and impact of imaging in the overall process of diagnosis and care of cancer patients, ACRIN has expanded the scope of the evaluation of imaging modalities beyond the traditional focus on diagnostic accuracy. Network studies examine the impact of imaging on the process of patient care and on patient outcomes, including complication rates, quality of life and functioning, satisfaction, and costs. In addition to providing evaluations of the impact of imaging technology, ACRIN data are used to formulate decision analytic models and clinical algorithms for the optimal use of imaging.

A conceptual overview of the network’s approach to the evaluation of imaging modalities can be presented in a matrix format (Table 2) with columns corresponding to the “developmental age” of the modality, and rows corresponding to different aspects of the “value” of the modality [3–5]. The developmental age of the modality can be categorized into four phases:

Table 2.

Matrix of imaging evaluation

| Endpoint | Phase | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discovery | Introductory | Mature | Disseminated | |

| Diagnostic/predictive performance | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Impact on process of care | no | sometimes possible | yes | yes |

| Impact on patient outcomes, cost-effectiveness | no | rarely possible | yes | yes |

Phase I (Discovery): Establishment of technical parameters and diagnostic criteria.

Phase II (Introductory): Early quantification of performance in clinical settings

Phase III (Mature): Comparison to other modalities in large, prospective, multi-institutional studies (efficacy).

Phase IV (Disseminated): Assessment of the procedure as utilized in the community at large (effectiveness).

The value of the modality is manifested in several domains, including (i) diagnostic and predictive performance (accuracy in cancer detection, lesion characterization, or prediction of response to therapy and long-term patient outcomes), (ii) impact on process of care, (iii) impact on patient outcomes and costs.

ACRIN studies concentrate on Phase III or advanced Phase II, which frequently dictates study design. Prospective designs are used in many but not all diagnostic performance studies. “Paired” designs are most efficient in comparative studies, with randomization used, if at all, to decide issues like the order in which patients will receive the imaging procedures. Diagnostic and staging studies are frequently conducted in conjunction with ongoing clinical trials of therapy conducted by other groups. Typical endpoints may include both diagnostic performance, and patient-level outcomes. This is also the case for studies of early detection technologies. As an example, the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) is a randomized, prospective study with lung cancer-specific mortality as the primary endpoint, while other ACRIN screening studies have a measure of diagnostic performance (e.g. ROC area or yield) as the primary endpoint. Endpoints for trials of image-guided therapy, such as the tumor ablation protocols 6661 (ablation of bone tumors), 6673 (ablation of liver tumors) and 6674 (ablation of breast tumors), can reflect technical success (e.g. radiographically successful tumor ablation), intermediate outcomes like palliation of pain, or ultimate health outcomes like patient survival.

As a result of ACRIN’s approach to the evaluation of imaging, ACRIN studies include a variety of secondary endpoints, spanning the spectrum presented above. The broad scope of ACRIN’s scientific agenda makes the tasks of the Biostatistics and Data Analysis Center considerably more multifaceted in comparison to traditional studies of imaging accuracy and to traditional studies of cancer treatment.

The Evolution of ACRIN’s Scientific Strategy

It would be hard to argue that ACRIN employed a defined strategy for trial selection and development during its most formative years. While the responders to the initial RFA were required to proffer ideas for possible ACRIN trials, the awarding of the grants did not require that these ideas actually be transformed into clinical trials. Despite this, the majority of the ideas put forth in the initial RFA response did eventually become a part of the ACRIN research portfolio. It would be fair to say that trying to accomplish so much in the way of organization-building and operational development while simultaneously trying to mount trials led to a “target of opportunity” approach to determining which ideas would succeed in the organization, which held through much of the initial funding period.

As part of the “open”, non-member nature of the network, it was agreed early on by the Steering Committee that ideas for trials could be submitted by anyone with an interest in imaging, including those who had neither previous contact with ACRIN nor involvement in its committee structure. If the Steering Committee prioritized the proposed trial idea highly, and the proposer appeared credible, ACRIN would build a trial team around that individual as the PI and develop the idea into an ACRIN trial. Trial ideas also could be generated by committee members or suggested by ACRIN leadership as the “most important” ones for trial development.

The original open strategy evolved rapidly during the first funding cycle of the network [6]. It became clear that a more cohesive strategic approach to imaging research was needed. It also became clear that the development and continued evolution of such a strategic approach requires a vibrant and active brain trust, which is closely articulated in the network. This led to an ever increasing role for and greater importance of the disease site committees. ACRIN developed a formal research strategy [7] requiring that all trial concepts submitted for Steering Committee consideration address one of “5 key hypotheses.” Concepts were required to be vetted, prioritized, and championed by the appropriate disease site committee before being forwarded to the Steering Committee for consideration in competition for ACRIN’s resources with other similarly handled concepts. The 5 key hypotheses were:

Imaging screening can improve the early detection of cancer and reduce disease-related mortality.

Image-guided therapy can improve the local control of malignancy and perhaps extend life.

Imaging can serve as an early indicator of therapeutic efficacy.

Molecular and functional imaging can improve detection, diagnosis, and staging of cancer.

Imaging informatics and other “smart systems” can improve enhance the information extracted from medical images.

These hypotheses served as the bellweather for the consideration of ideas for trials during ACRIN’s second funding period. In preparation for applying for the upcoming renewal (application submitted April 2007), ACRIN’s strategy has undergone further evolution to keep pace with both developments in imaging and in cancer diagnosis and treatment more broadly. Designed under the leadership of Dr. Mitchell Schnall, who will assume ACRIN’s Chair in 2008, the new strategy is structured around three primary objectives:

Develop strategies for imaging surveillance of populations at increased risk for cancer. The intent is to employ advances in understanding the genetics of oncology and the impact of environmental influences on the development of cancer to improve risk stratification as a way of tailoring the rigorousness of the screening approach to subjects’ level of cancer risk. This has the potential to make imaging screening more efficient and cost-effective.

Establish imaging approaches to characterizing disease anatomy, physiology and biology to guide targeted treatment. Emerging molecular imaging methods have the potential to provide a more detailed analysis of the extent and aggressiveness of tumors than has been viable with conventional methods. Collaborating with other groups, ACRIN will continue to insert its expertise into therapeutic trials when there is both the potential to enhance the primary endpoints and address an important research question with respect to imaging. By so doing, ACRIN will employ imaging to address key aspects of tumor biology, such as blood flow, hypoxia, apoptosis, and other molecular expression, that can help better support treatment decisions.

Identify, standardize, and validate imaging biomarkers of treatment response. As detailed above, medical imaging, particularly molecular imaging, has the potential to predict what treatment might be most effective for a given tumor and then determine the extent to which a treatment is working earlier and more accurately than currently. However, in most cases, there is no standardized protocol for how these imaging examinations should be performed and the images analyzed. ACRIN already is involved in standards development and improving image information extraction for many of these modalities and expects to continue to expand upon this expertise in the third funding cycle.

ACRIN’s evolving agenda reflects current major trends in imaging technology and its role in modern cancer care. Two such developments constitute the basis of a growing consensus that imaging is now called to reflect molecular and functional processes.

In addition to images used for qualitative interpretation, the newer imaging modalities generate quantitative information. The standard uptake value (SUV) for fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET imaging is perhaps the most commonly known among the new quantitative measures, but there are several others for modalities, such as DCE MRI and MR spectroscopy. Thus imaging data are moving beyond the traditional qualitative reader interpretations and have properties similar to those of other laboratory-based biological measurements.

There is increasing recognition of the potential for imaging to provide information that can be used to customize therapy before it is administered or to alter therapy early in the course of its administration.

These developments have moved ACRIN into the evaluation of imaging as a biomarker for the activity of cancer treatment. Indeed the majority of recent ACRIN protocols address these issues, and increasingly they are studies conducted in collaboration with the other cooperative groups. An important precondition for the success of such studies is to ensure that new imaging approaches and the derivation of quantitative measurements from images can be implemented in a reliable and reproducible fashion across multiple participating sites. To this end, ACRIN has recently chartered its Experimental Imaging Sciences Committee (EISC). The EISC has status similar to disease site committees, in that it has the potential of developing clinical trials, however, its role is unique. The EISC is charged with conducting small multi-center pilot studies to serve as the translational bridge between first-in-human use and more intensive evaluation. This is a critical function, since early, single institutional testing often will provide an optimistic view of a new imaging approach that must be validated in subsequent research. In essence, the EISC will work with disease site committees and the ACRIN imaging core laboratory (described below) to qualify new imaging and image data extraction methods for consideration of phase II and phase III trials.

The Selection of ACRIN Trials

The scientific committees are charged with developing and periodically updating disease site-specific strategies to guide their deliberations of which trial concepts they will entertain in the context of the organizational strategy. Each committee prioritizes trial ideas (which may still come from any source) and determines which ideas to develop into initial concepts and forward to the Steering Committee for consideration. An extensive document of scientific committee strategies was developed in preparation for the second funding cycle (7). The committees have done the same for the current renewal application. The sum of the committee strategies represents the composite scientific strategy of ACRIN.

ACRIN seeks to conduct the most important trials of diagnostic imaging and image-guided treatment technologies for cancer patients. A number of factors are considered in making this assessment:

Prevalence of the condition

Given the large number of disease/imaging technology pairs that might be evaluated in ACRIN trials and the limitations of its resources, ACRIN has chosen to focus mainly on commonly encountered malignancies.

Morbidity caused by a cancer

ACRIN considers the extent to which a cancer causes human suffering and death.

Potential impact an imaging technology might have in reducing morbidity and mortality

ACRIN seeks to employ in its trials imaging modalities that will have a significant impact on health outcomes.

Opportunity to go beyond evaluation of the accuracy of a technology to determine the effect of employing an imaging modality on health and cost

Most assessments of imaging technology focus on how well the modality differentiates between normal and abnormal structures. ACRIN seeks to go beyond this determination to evaluate how using an imaging method affects diagnostic and therapeutic decision-making, patients’ health, and health care expenditures.

Opportunity to address cancers that disproportionately affect disadvantaged populations

ACRIN’s Special Populations Committee is charged with advising the Steering Committee on opportunities to conduct trials that will provide disadvantaged populations with early access to promising imaging technologies and how to improve minority accrual to ACRIN trials.

Key ACRIN Trials

ACRIN has been involved in 29 trials since it began operations and accrued around 75,000 subjects. The protocols and forms for all active and analyzed ACRIN trials are posted on the Web site and available for use by any interested investigator. While all of ACRIN trials have been carefully vetted to ensure they address important cancer-related questions, some that have had or are expected to have in the future particularly significant impact. Three of these are large screening trials that have the potential to advise reimbursement policy for screening for commonly encountered cancers.

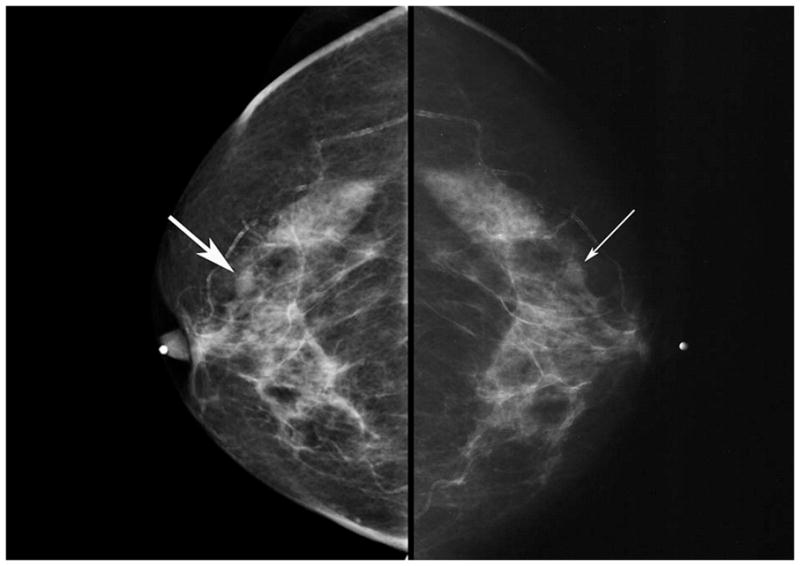

ACRIN 6652: Digital Mammographic Imaging Screening Trial (DMIST)

Digital mammography is an electronic method of capturing breast images on an electronic substrate rather than film. Enthusiasts had hypothesized that this would allow better diagnosis by permitting better equalization of gray scale, improved sharing of images with experts, more reliable availability of previous images for comparison, and more universal access to expert subspecialist interpretation. ACRIN’s DMIST, sponsored by a funding supplement from NCI and supported by the (then) four manufacturers of digital mammography equipment, was designed to compare the diagnostic performance of digital and film-screen mammography. DMIST accrued 49,520 asymptomatic women on schedule. All women received both digital and conventional mammography (Figure 2). Each image was interpreted by a separate radiologist, so that the downstream effects of digital and conventional mammography on diagnosis, utilization, and costs could be calculated separately. The trial did not show a significant difference between the two technologies across the entire sample, however, digital mammography showed superior performance for women who were younger, peri-menopausal, and had dense breasts [8]. DMIST results have had a powerful impact on the dissemination of digital mammography equipment and the use of digital mammography on women who can benefit from its application. The outcome of the trial also resulted in FDA reducing the regulatory barriers for approval of digital mammography devices.

Figure 2.

Digital (left) and film-screen (right) mammograms of the same subject showing an infiltrating ductal carcinoma (arrows) in a woman with radiographically dense breasts. The lesion was observed on digital mammography but missed on the film-screen examination, probably because of the greater contrast of the digital mammogram.

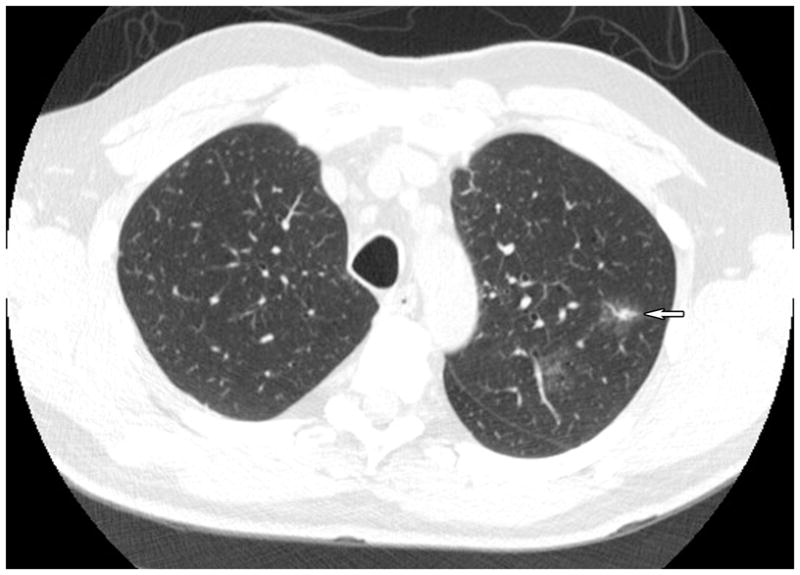

ACRIN 6654: National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) [9]

Observational studies of CT screening for lung cancer have shown a positive effect (10–11). However, a more recent study comparing the results of an observational study to a modeled comparison group demonstrated no benefit in mortality reduction (12), putting the benefit of CT screening in doubt. Since 2001, ACRIN has been collaborating with the Lung Screening Study consortium to conduct a randomized trial of screening CT in an effort to definitively determine whether using CT to screen individuals at high risk for lung cancer (using age and smoking history as indicators of risk) reduces lung cancer-specific mortality. More than 50,000 subjects were accrued on schedule. Subjects were randomized to either low dose CT or chest radiography for their initial examination and received two sequential annual screens with the same technology (Figure 3). Subjects currently are being followed on a semi-annual basis to determine whether they have contracted lung cancer and whether they have died of the disease. The results, expected to be reported in 2010, are expected to influence public policy on CT screening for lung cancer.

Figure 3.

CT scan of the thorax, axial image, showing a 1.8 cm, irregularly speculated, peripheral lung mass (arrow) in the left lung periphery. The lesion is a well-differentiated bronchoalveolar cell carcinoma without radiographic or surgical evidence of dissemination.

ACRIN 6664: National CT Colonography Trial (NCTCT)

Colon cancer is a significant health problem in the U.S. and worldwide - one that is potentially susceptible to improvement by early detection and treatment. The pre-clinical phase of colon cancer (represented by adenomatous polyps) is lengthy, and optical colonoscopy is a highly sensitive test for these lesions. However, because of the discomfort and time needed to get a colonoscopy, only a minority of the U.S. target population adheres to screening recommendations. CT colonography is a new imaging-based screening technology that requires neither sedation nor as much time lost from work. Prior trials of CT colonography have reported differing results, some quite optimistic and others less so [13–15]. The NCTCT was designed as a “decider trial.” The trial has recruited on schedule 2600 asymptomatic subjects. All subjects received both CT colonography and optical colonoscopy. If the results differed, subjects received a second colonoscopy for which the operator had the CT colonography results. The analysis is based on a pairing of colonoscopy and CT colonography lesions, for which the colonoscopy is the reference standard. The results of the trial are currently under analysis and will be reported at the ACRIN Annual Meeting in late September 2007.

ACRIN 6657: MRI to evaluate the response to neoadjuvant treatment for advanced breast cancer

A critical issue for all of oncology is how to hasten the time required and improve the accuracy of predictors of the effectiveness of treatment. Delays associated with current anatomic measurements of tumor cause unnecessary morbidity and expense and waste precious time that might be used to administered more appropriate therapy. Functional and molecular imaging tests have shown promise in small single institutional trials for perhaps improving on anatomic measurements. ACRIN has collaborated with the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) to conduct a study of subjects with advanced breast cancer undergoing neoadjuvant treatment. The trial evaluates DCE-MRI and volumetric analysis of the breast lesions to predict whether treatment will be successful. The full complement of 231 subjects was accrued on schedule. Each patient received four sequential MRI scans and core biopsies - at the outset, after each treatment cycle, and prior to surgery. The cohort is undergoing follow-up for outcomes evaluation and imaging analyses are being conducted. A protocol has been developed to add another 114 subjects who will receive MRS to assess the effectiveness of treatment. The trial represents a paradigm that ACRIN hopes to repeat into the future, wherein clinical, tissue, genomic, and imaging data are available for extensive correlation to elucidate oncological biology.

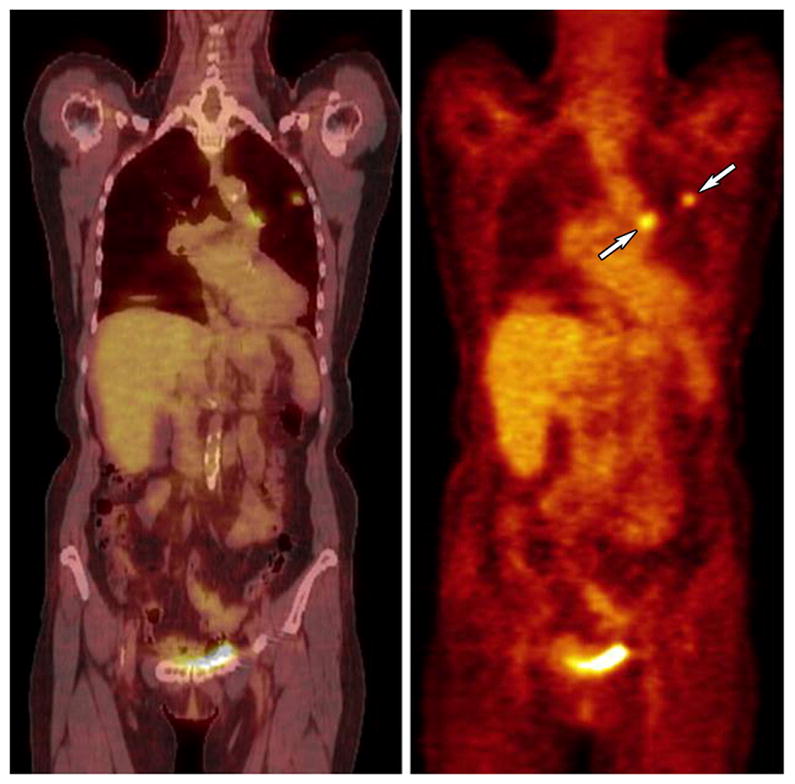

ACRIN 6678: PET evaluation of standard therapy for surgically non-resectable non-small cell lung cancer

Fluorine(18)-deoxyglucose (FDG) PET has shown promise as a technology capable of evaluating tumor glucose metabolism, and hence, viability. One of the problems of broadly instituting FDG-PET for this purpose is that there is no standard and uniform approach to performing PET procedures and poor agreement on whether to use subjective or quantitative measurements of radionuclide activity. ACRIN 6678 seeks to demonstrate that PET can be standardized in a multi-center clinical trial and can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of standard treatment for non-resectable small cell lung cancer (Figure 4). The trial has just opened with the expectation that it will accrue 228 subjects.

Figure 4.

Coronal CT (left) and PET (right) images of a peripheral lung cancer with central nodal activity (arrows) indicating mediastinal metastasis.

ACRIN 6661: Radiofrequency ablation of bone metastases for intractable pain

Intractable skeletal pain related to metastatic malignancy is a significant cause of cancer-related suffering. Standard treatment usually consists of localized radiation therapy and narcotic pain medications. A new technology that is has demonstrated effectiveness in a number of tissues is radiofrequency ablation (RFA). RFA translates radiofrequency energy into heat that is transmitted to the tip of a percutaneous probe inserted directly into the tumor. The idea is to kill the tumor cells while damaging normal tissue as little as possible. ACRIN 6661 accrued 66 subjects suffering severe skeletal pain. Preliminarily, the analysis demonstrates a significantly positive effect in reducing debilitating symptoms.

ACRIN in the Future

ACRIN is cognizant that as the organization matures, more will be expected of it. The network will undergo its first major change in leadership in 2008, as Dr. Mitchell Schnall succeeds ACRIN’s founding Chair, Dr. Bruce Hillman. ACRIN also expects to initiate its third funding cycle with a very imposing agenda. Over its first nine years of existence, ACRIN has developed a set of unique resources: a track record of successfully conducting imaging clinical trials; the infrastructure to conduct increasingly important trials into the future; an image archive of greater than 15 million images that can be employed for secondary research not only by ACRIN but by request from other academics and industry; and a recognized position as the experts in clinical imaging research within the cancer research community.

To put these resources in the service of improving cancer care, ACRIN has accelerated its development of its imaging core laboratory. The core laboratory is the locus for image transmission, archival, quality assurance, and image information extraction. There is an increasing focus on quantitative image information with a slant towards developing new approaches to measuring the information provided by functional and metabolic imaging technologies. ACRIN intends to use these facilities not only for its own trials but as a resource for other research groups that would like to better employ imaging in their own trials. To further address its goals, ACRIN has assumed an important role in the caBIG Imaging Workspace as its sole funded organizational member. caBIG is the NCI effort to electronically interconnect all aspects of the national cancer research enterprise and provide researchers with the tools needed for greater collaboration and efficiency and optimal exploitation of imaging data. As such, ACRIN will both contribute innovations to the endeavor and serve as a test bed for the contributions of others.

ACRIN also expects to leverage what it has been able to accomplish with its federal funding to more broadly engage the device, biological, and pharmaceutical industries in its primary research agenda and by providing core lab and other research services to assist in bringing to market important new technologies. Particularly with respect to therapeutic agents, imaging will play an increasingly important role as industry employs such endpoints as time-to-progression and progression-free-survival – endpoints for which imaging is especially well suited. Involved as ACRIN is in the standardization and investigation of new imaging technologies that can serve as biomarkers of treatment effectiveness and perhaps reduce the cost and time it takes to conduct regulatory trials, the organization should appeal to industry as a worthy collaborator.

Finally, ACRIN has developed the capacity to complement its clinical trials capabilities with the formation of registries. Registries can be employed in circumstances for which formal trials are either inappropriate or too expensive to be practical or when a “real world” observational view is what is needed. ACRIN’s National Oncologic PET Registry (NOPR) is an example of a how a registry can provide information for regulatory or reimbursement agencies to formulate policy. ACRIN collaborated with the American College of Radiology and the Academy of Molecular Imaging to work with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to initiate and maintain the NOPR as an initiative by CMS to provide “coverage with evidence development” for PET applications to cancer. As of June 2007, more than 1,500 institutions have received reimbursement for over 33,000 patients receiving previously non-reimbursable examinations by supplying information that will allow ACRIN researchers to determine how PET affects diagnostic and therapeutic decision-making. CMS will ultimately use the data to make PET coverage determinations.

ACRIN’s formative years have left the organization in an enviable position to pursue more and even more significant clinical trials in the future.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hillman BJ, Gatsonis C, Sullivan DC. American College of Radiology Imaging Network: new national cooperative group for conducting clinical trials of medical imaging technologies. Radiology. 1999;213(3):641–5. doi: 10.1148/radiology.213.3.r99dc38641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black WC, Welch HG. Screening for disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;168:3–11. doi: 10.2214/ajr.168.1.8976910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fryback DG, Thornbury JR. Efficacy of diagnostic imaging. Medical Decision Making. 1991;11:88–94. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9101100203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gatsonis CA. Design of evaluations of imaging technologies: development of a paradigm. Acad Radiol. 2000;7:681–683. doi: 10.1016/s1076-6332(00)80523-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Houn F, Bright RA, Bushar HF, Croft BY, et al. Study design in the evaluation of breast cancer imaging technologies. Acad Radiol. 2000;7:684–692. doi: 10.1016/s1076-6332(00)80524-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hillman BJ, Gatsonis C, Schnall MD. The ACR imaging network: A retrospective on 5 years of conducting multicenter trials in radiology and plans for the future. J Am Coll Radiol. 2004;1:346–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2004.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aberle DR, Chiles C, Gatsonis C, et al. Imaging and cancer: research strategy of the American College of Radiology Imaging Network. Radiology. 2005;235:741–51. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2353041760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pisano E, Gatsonis C, Hendrick RE, et al. Diagnostic performance of digital vs. fil mammography for breast cancer screening. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1773–1783. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Church TR. Chest radiography as the comparison for spiral CT in the National Lung Screening Trial. Acad Radiol. 2003;10:713–715. doi: 10.1016/s1076-6332(03)80095-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henschke CI, McCauley DI, Yankelevitz DL, et al. Early Lung Cancer Action Project: overall design and findings from baseline screening. Lancet. 1999;354:99–105. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)06093-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henschke CI, Yankelevitz DF, Libby DM, et al. Survival of patients with stage I lung cancer detected on CT screening. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1763–1771. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bach PB, Jett JR, Pastorino U, et al. Computed tomography screening and lung cancer outcomes. JAMA. 2007;297:995–997. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson CD, Harmsen WS, Wilson LA, McCarty RL, Welch TJ, Ilstrup DM, Ahlquist DA. Prospective blinded evaluation of computed tomographic colonography for screen detection of colorectal polyps. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:311–319. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00894-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cotton PB, Durkalski VL, Pineau BC, et al. Computed tomographic colonography – a multi-center comparison with standard colonoscopy for detection of colorectal neoplasia. JAMA. 2004;291:1713–1719. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.14.1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pickhardt PJ, Choi JR, Hwang I, et al. Computed tomographic virtual colonoscopy for colorectal neoplasia in asymptomatic adults. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2191–2200. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]