Abstract

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) and pp65 antigenemia assays are used to monitor cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection in renal transplant recipients, but correlation of assays in a pediatric population has not been evaluated. Paired CMV real-time qPCR and pp65 antigenemia tests from 882 blood samples collected from 115 pediatric renal transplant recipients were analyzed in this retrospective cohort study for strength of association and clinical correlates.

The assays correlated well in detecting infection (κ = 0.61). Higher qPCR values were demonstrated with increasing levels of antigenemia (p < 0.01). Discordant test results were associated with antiviral treatment (OR 4.33, p < 0.01) and low-level viremia, with odds of concordance increasing at higher qPCR values (OR 3.67, p < 0.01), and no discordance occurring above 8500 genomic equivalents/mL. Among discordant samples, neither test preceded the other in detecting initial infection or in returning to negative while on treatment. Only 2 cases of disease occurred during the 2-year study period.

With strong agreement in the detection of CMV infection, either qPCR or pp65 antigenemia assays can be used effectively for monitoring pediatric renal transplant patients for both detection and resolution of infection.

Keywords: Pediatrics, Kidney Transplantation, Cytomegalovirus Infections, Polymerase Chain Reaction, CMV pp65 Antigen

INTRODUCTION

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection remains an important cause of morbidity in transplant recipients. In addition to causing acute disease, CMV infection and disease have also been associated with indirect effects such as graft rejection, secondary infections, and mortality (1-5). Monitoring for CMV infection in this population is used to guide antiviral therapy to prevent CMV disease.

Both pp65 antigenemia and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) assays are routinely utilized in adult transplant populations to detect CMV infection. Higher levels of pp65 antigenemia and higher qPCR viral loads have each been associated with a higher incidence of CMV disease (6-12). Several centers have demonstrated that the two assays correlate in adult solid organ transplant (SOT) recipients (13-16), and others have determined qPCR threshold values that correspond to previously established antigenemia cutoff levels for preemptive therapy (17-22). Prospective trials comparing pp65 antigenemia and qPCR for monitoring and initiating preemptive therapy found that fewer patients required treatment in the qPCR arms without any corresponding increase in CMV disease in both SOT (23) and hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) populations (24, 25). Factors such as neutropenia, low-level viremia, and antiviral treatment have been implicated as potential contributors to discordant results between the two tests.

A direct comparison between pp65 antigenemia and qPCR assays has not been investigated in an exclusively pediatric population. This group differs from adult patients in various ways including having a higher proportion of CMV naïve organ recipients, differing underlying etiologies for end-organ failure, and fewer comorbid conditions (26). In this study, paired antigenemia and qPCR blood tests from pediatric renal transplant recipients were performed in parallel. The strength of association between paired assays and their clinical utility in detecting development of disease were assessed to determine the optimal assay for monitoring pediatric renal transplant recipients.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patient Samples

The University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) Institutional Review Board approved this retrospective cohort study. Subjects were pediatric renal transplant recipients followed at UAB during a two-year period of paired blood testing (May 10, 2007 to April 2, 2009) performed according to clinical protocol. Medical records of these patients were screened to include only subjects who were current recipients of a renal transplant (without other organ transplantation) that was performed at UAB, ≤ 18 years old at time of transplant, and ≤ 21 years old at the time of the diagnostic test. All other patients were excluded. The records of the included subjects were reviewed to obtain clinical information regarding transplant history and other parameters at the time of the paired tests.

Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction

A published in-house real-time TaqMan assay targeting the highly conserved AD-1 region of CMV glycoprotein B (gB) was used to test the whole blood samples for clinical purposes (27), with the following modifications. The forward (5′-AGG TCT TCA AGG AAC TCA GCA AGA) and reverse (5′-CGG CAA TCG GTT TGT TGT AAA) primers were used with an internal probe (5′-ACC CCG TCA GCC ATT CTC TCG GC) labeled at the 5′end with a fluorescent reporter dye 6-carboxyfluorescein (FAM), and the 3′end with a quencher dye 6-carboxytetramethylrhodamine (TAMRA). The ABI Prism 7300 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems) was used to perform the assay on 25-μL reaction mixtures, each of which contained 20 μL of master mix and 5 μL of the test-sample DNA preparation. The qPCR-cycle parameters were incubation at 50°C for 2 min and at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 45 cycles at 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min.

A purified plasmid (pTZG) containing the target sequence of the CMV gB was quantitated spectrophotometrically to establish a standard. Serial 10-fold dilutions of these plasmid standards were used to quantitate CMV DNA in the test samples. The standards and test samples were run in triplicate, and the average values were used to determine the CMV viral load in genomic equivalents per milliliter (ge/mL). To control for preparation and amplification of the sample, primers for amplification of the human albumin gene were included in each qPCR assay. The qPCR conditions were optimized for the amplification of the target gene such that the sensitivity of the assay was ~50 ge/mL of standard, with a dynamic range of 102 – 108 ge/mL. For the purposes of these analyses, subjects with ≥200 ge/mL were considered to be viremic. This cutoff value was based on its equivalence to 1 virion/5 μL of test sample, which was the lowest limit of detection for this assay.

Antigenemia Assay

To measure pp65 antigenemia, a commercial assay (“CMV Brite Turbo Kit,” IQ Products, The Netherlands) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Per the package insert, a minimum of approximately 50,000 cells per slide is needed to yield a valid negative result. Whole blood samples were prepared with a goal dilution of 2000 WBC/μL. 100 μL of this suspension was applied to each slide, for a target count of 200,000 WBC/slide. Duplicate slides were prepared for each sample, and a positive test for an individual sample was defined as the presence of one or more CMV antigen-positive cells per set of slides.

Although this test is licensed as a qualitative result (positive or negative), quantitative results measured by the number of positive cells per sample slide were also recorded by the technician and made available to the clinician upon request. For the quantitative analysis, 1 positive cell per set of slides were rounded to a value of 1 positive cell/slide, and >100 positive cells/slide was reassigned a value of 100 positive cells/slide.

Clinical CMV Management Protocols

All patients underwent routine prospective screening for CMV infection according to the following post-transplantation protocol: weekly for the first month, biweekly through the fourth month, monthly through the first year, then every third month thereafter. Patients also underwent testing for evidence of CMV infection as clinically indicated. The majority of patients received a standard immunosuppressive regimen immediately following transplant consisting of daclizumab, mycophenolate mofetil, tacrolimus, and a prednisone taper. Patients received antiviral prophylaxis for at least 90 days after transplant regardless of recipient serostatus, consisting of 7 days of intravenous therapy with subsequent change to an oral agent. CMV donor-positive/recipient-negative (D+/R-) patients received at least 6 months of prophylaxis. Prior to October 2007, prophylactic valganciclovir was used only for CMV or Epstein-Barr virus D+/R− recipients, while acyclovir or ganciclovir prophylaxis was used for all other patients. From October 2007 onward, valganciclovir has been the oral prophylactic agent for all recipients regardless of D/R status.

Antiviral treatment for CMV infection given at any point following transplant, either preemptively or for disease, consisted of intravenous ganciclovir following approved dosing, or oral valganciclovir according to discretion of the clinician, all adjusted for creatinine clearance. Standard duration of treatment during the study period was 21 days. Pre-emptive therapy was initiated based on the individual clinical judgment of the treating physician. Both qPCR and qualitative antigenemia results were reported to the clinician, with quantitative antigenemia results made available upon request.

Definitions

For this study, CMV infection was defined as having a positive blood test for CMV by antigenemia or qPCR assays. Definitions of CMV syndrome and invasive disease were adapted from recognized international guidelines (28, 29). CMV syndrome consisted of unexplained fever for >38.0°C for at least 2 days, CMV detected in blood by at least one test, and one or more of the following unexplained signs and symptoms: malaise, leukopenia, atypical lymphocytosis, thrombocytopenia, or transaminitis. CMV disease was defined as end-organ disease such as gastrointestinal disease, pneumonitis, or retinitis with CMV detected in blood by at least one test with or without confirmatory detection of CMV in tissue (bronchoalveolar lavage [BAL], biopsy, or ophthalmologic exam) and negative tests for other etiologies. For our analyses, neutropenia was defined as an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) of < 1000/mm3.

Statistical Analyses

Demographic characteristics were described as categorical variables (race, gender, etc.). For continuous variables, means and standard deviations were calculated. The outcome variables of positive antigenemia or positive qPCR tests were summarized as proportions and the Kappa statistic (κ) was calculated to describe the degree of agreement between the paired tests. Statistical models were developed to measure association between clinical and demographic characteristics with discordance between antigenemia and qPCR tests. Because individuals had repeated observations of discordance, Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) were used to account for non-independence due to repeated observations. Separate secondary models examining each type of disagreement (qPCR-positive/antigen-negative, qPCR-negative/antigen-positive) were also constructed using GEE modeling. Finally, to examine the influence of a large number of individuals who only presented concordant antigen and qPCR negative results, another secondary analysis was conducted restricting to individuals who had at least one positive test. To examine whether test results provided predictive ability regarding subsequent pairs of tests, lag-1 regression models were developed measuring the association between a test result and the preceding test results. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.2 (Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Nine hundred thirty-two whole blood samples from 133 patients underwent prospective paired testing for CMV infection by both pp65 antigenemia and qPCR over a two-year span (May 10, 2007 to April 2, 2009) according to clinical protocol at the UAB Diagnostic Virology Laboratory. Exclusion criteria reduced the data set to 882 samples from 115 patients.

Characteristics of the 115 patients are listed in Table 1. Notable features of this population include a 67% male predominance, 54% who received kidney grafts from living donors, 34% from the high-risk D+/R− group, 78% who had a genetic or structural underlying renal disorder that led to renal failure, while 22% had immune-mediated processes (Table 2).

Table 1. Patient Demographics.

| Variable | Patients (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 77 (67) |

| Female | 38 (33) | |

| Race | White | 59 (51) |

| Black | 48 (42) | |

| Hispanic | 6 (5) | |

| Other | 2 (2) | |

| Age at Transplant | 0 – 5 | 26 (23) |

| 6 – 12 | 21(18) | |

| ≥ 13 | 68 (59) | |

| Donor Source | Living | 62 (54) |

| Deceased | 53 (46) | |

| D/R CMV Status | D−/R− | 28 (24) |

| D−/R+ | 5 (4) | |

| D+/R− | 39 (34) | |

| D+/R+ | 26 (23) | |

| At least one missing | 17 (15) | |

| Post-transplant Antiviral Prophylaxis | Valganciclovir | 73 (63) |

| Ganciclovir | 12 (10) | |

| Acyclovir | 22 (19) | |

| Mixed | 3 (3) | |

| Unknown | 5 (4) | |

| Underlying Diagnosis | Genetic/Structural | 90 (78) |

| Immune-mediated | 25 (22) | |

| Transplant Number | First | 108 (94) |

| Second or more | 7 (6) | |

| Neutropenia During Test Period | ANC < 1000/mm3 | 20 (17) |

| Antiviral Treatment During Test Period* | 11 (10) | |

| Received Immunosuppressive Agents Other Than Tacrolimus or Mycophenolate Mofetil During Test Period |

Sirolimus | 17 (15) |

| Cyclosporine | 3 (3) | |

| Azathioprine | 7 (6) | |

| More than 1 | 1 (1) | |

Antiviral treatment for CMV infection given at any point following transplant, either preemptively or for disease, with intravenous ganciclovir following approved dosing, or oral valganciclovir according to our center protocol, all adjusted for creatinine clearance.

Table 2. Categories of Underlying Renal Disease Diagnoses.

| Genetic/Structural | Immune-mediated and/or Treatable |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Aplastic/hypoplastic/dysplastic kidneys | Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis |

| Obstructive uropathy | Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis - Type I |

| Syndrome of agenesis of abdominal musculature (Prune Belly) | Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis - Type II |

| Polycystic kidney disease | Membranous nephropathy |

| Medullary cystic disease/juvenile nephronophthisis | Idiopathic crescentic glomerulonephritis |

| Familial nephritis - Alport’s Syndrome | Chronic glomerulonephritis |

| Cystinosis | Pyelonephritis/interstitial nephritis |

| Oxalosis | Reflux nephropathy |

| Wilms’ tumor | SID w/SLE nephritis |

| Renal infarct | SID w/Henoch-Schonlein purpura nephritis |

| Diabetic glomerulonephritis | SID w/Berger’s nephritis (IgA) |

| Sickle cell nephropathy | SID w/Wegener’s granulomatosis |

| Hemolytic uremic syndrome | SID w/other |

| Drash syndrome | Post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis |

| Congenital nephrotic syndrome | |

| Unknown/Other | |

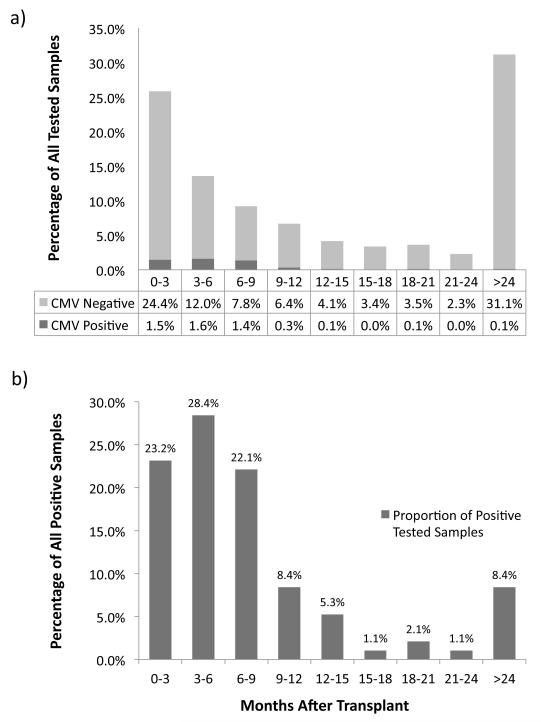

As expected per protocol, the number of samples drawn for testing decreased as time from transplant increased (Figure 1a). Of the 882 samples, 358 (40.6%) were drawn from patients receiving antiviral agents at prophylactic doses, 64 samples (7.3%) were from patients receiving antiviral medications at treatment doses, and 35 (4.0%) samples were drawn from patients with neutropenia. The lowest ANC among the samples was 339/mm3, and valid pp65 antigenemia tests were performed on all 882 samples.

Figure 1. Timing of CMV Tested Samples After Transplant.

a) All tested samples: 882 samples from 115 patients were tested for CMV. The proportions of all tests are shown by the time (in months) they were drawn after transplant; each bar depicts the percentage of tests that were negative by both tests (CMV Negative, light bar), or positive by at least one test (CMV Positive, dark bar). The sample tested the longest time after transplant was drawn at 184 months post-transplant.

b) Positive tested samples: 95 samples from 31 patients tested positive for CMV. The proportions of positive tests are shown by the time drawn after transplant. The positive sample observed latest after transplant was drawn at 155 months post-transplant.

Detection of CMV Infection

Thirty-one patients (27.0%) tested positive for CMV infection by any test for a total of 95 positive samples during the study period, half of which occurred during the first 6 months after transplant (Figure 1b). Twenty-eight positive samples (29.5%) were from patients receiving antiviral prophylaxis, and 60 positive samples (63.2%) came from D+/R− patients. Thirty-seven samples from 11 of these patients received antiviral treatment for infection.

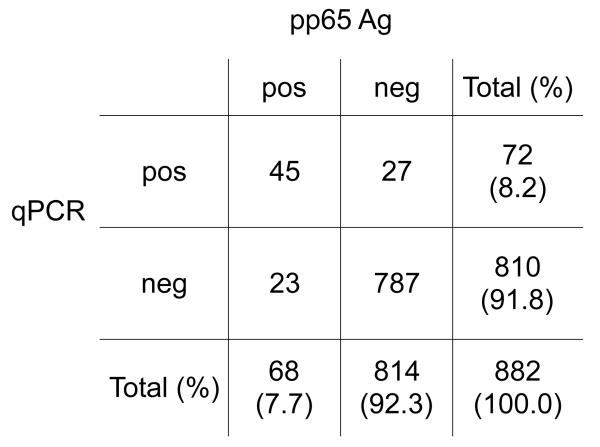

Of the 882 total samples, 72 (8.2%) were positive by the qPCR assay (range: 200 – 66,700 ge/mL), while 68 (7.7%) were positive by the pp65 antigenemia assay (range: 1 positive cell/slide set – >100 positive cells/slide) (Figure 2). When accounting for pairing of test outcomes as well as repeated observations within individuals, there was no significant difference in positive detection rate between the two methods (p = 0.75).

Figure 2. Agreement between Paired CMV DNA qPCR and pp65 Results.

Blood samples underwent paired CMV testing by qPCR and pp65 antigenemia according to clinical protocol. 50 total discordant pairs (5.7%) were observed from 28 patients (24%). Kappa (κ) = 0.612, signifying strong agreement between test results.

Eight hundred and thirty-two samples gave concordant results, with 45 samples positive by both assays, and 787 samples both negative. Kappa (κ), which measures the strength of association between the two tests, was 0.61 (95% CI 0.51 – 0.71), indicating strong agreement. However, 50 samples (5.7%) yielded discordant results; 23 pairs were qPCR-negative/antigen-positive, and 27 were qPCR-positive/antigen-negative.

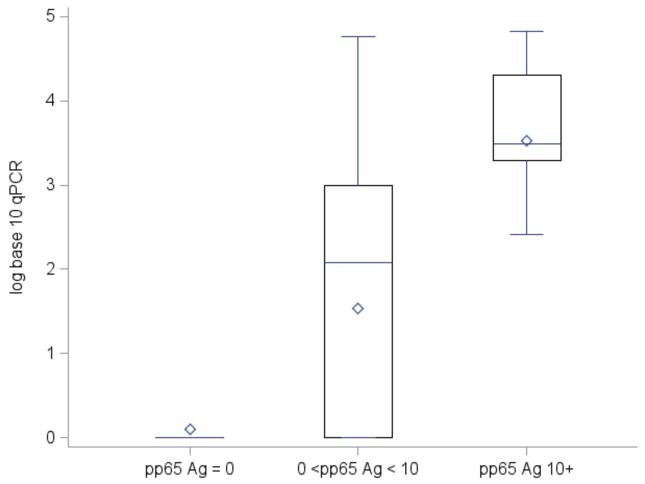

Among samples with at least one positive test, sequential groupings of quantitative pp65 antigenemia results (0, 1 – 10, and ≥ 10 pp65 antigen-positive cells) correlated well with corresponding qPCR results. Separate box plots of log10 qPCR quantities to compare quantiles, medians, means, and spread among categories demonstrated that as antigenemia quantity increased, the mean and median log10 qPCR levels also increased (p < 0.01) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Log10 CMV qPCR by Paired Quantitative pp65 Antigenemia Category.

Quantitative CMV pp65 antigenemia results were categorized into 3 ranges: 0, 1 – 10, and ≥ 10 pp65 antigen-positive cells. Separate box plots of log10 CMV qPCR quantities were built to compare quantiles (25th to 75th percentile), medians (◇), means ( ), and spread (whiskers: ⊥) among categories. For samples with 0 antigen-positive cells, the mean log10 CMV qPCR was 0.10 (median 0, standard deviation 0.55); for those between 1 – 10 antigen-positive cells, 1.63 (median 2.18, standard deviation 1.62); for those ≥ 10 antigen-positive cells, 3.49 (median 3.49, standard deviation 1.03). The mean and median log10 CMV qPCR quantities were significantly greater for increasing pp65-antigenemia test quantities among the three categories (p < 0.01). The multiple qPCR positive tests within the pp65 = 0 category reflect discordant results.

), and spread (whiskers: ⊥) among categories. For samples with 0 antigen-positive cells, the mean log10 CMV qPCR was 0.10 (median 0, standard deviation 0.55); for those between 1 – 10 antigen-positive cells, 1.63 (median 2.18, standard deviation 1.62); for those ≥ 10 antigen-positive cells, 3.49 (median 3.49, standard deviation 1.03). The mean and median log10 CMV qPCR quantities were significantly greater for increasing pp65-antigenemia test quantities among the three categories (p < 0.01). The multiple qPCR positive tests within the pp65 = 0 category reflect discordant results.

A sub-analysis was performed in which patients who never tested positive by either test were excluded. This eliminated 474 qPCR-negative/antigen-negative samples for a remaining total of 408 samples from 31 patients. Among the samples with any positive test, there was still moderate agreement between assays (κ = 0.57, 95% CI 0.46 –0.68).

Discordant Results

The 50 samples with discordant test pairs were next examined to assess any differences in assay performance (Table 3). When observed, any discordant pair regardless of type had higher odds of being preceded by a discordant pair (OR 4.40, 95% CI 2.13 – 9.10, p < 0.01), indicating that discordant samples were more likely to occur in series than alone. However, 17 of the 50 (34%) discordant samples occurred within 30 days of a concordantly positive sample, of which 5 samples (3 qPCR-negative/antigen-positive and 2 qPCR-positive/antigen-negative) preceded a positive pair, while 12 samples (7 qPCR-negative/antigen-positive and 5 qPCR-positive/antigen-negative) followed a positive pair.

Table 3. Characteristics of Discordant Samples.

| Variable | Number of Discordant Samples (n = 50) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Any Discordant (%) | qPCR-positive/antigen-negative | qPCR-negative/antigen-positive | |

| D+/R− CMV Status | 26 (52.0) | 9 | 17 |

| Concurrent Antiviral Treatment | 14 (28.0) | 5 | 9 |

| Concurrent Antiviral Prophylaxis | 15 (30.0) | 7 | 8 |

| Neutropenia (ANC <1000/mm3) | 6 (12.0) | 2 | 4 |

| Within 30 Days of a Concordant Positive Sample | 17 (34.0) | 7* | 10** |

2 samples preceded the concordant pair, 5 samples followed.

3 samples preceded the concordant pair, 7 samples followed.

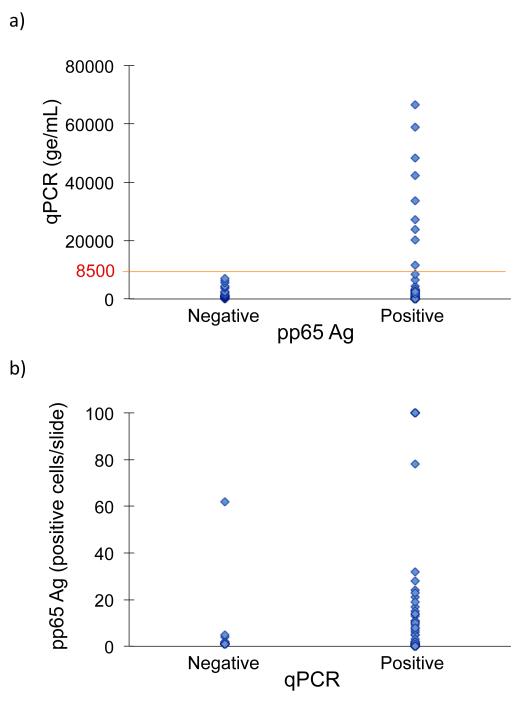

Discordant results occurred most often in samples with lower quantitative genome copies. Concordance was associated with the log10 level of qPCR (p < 0.01), such that each log unit increase raised the odds of concordance by a factor of 3.67. As such, among subjects with at least one positive test, discordance was not observed beyond a qPCR threshold value of 8500 ge/mL (Figure 4a); only concordant positive results were observed above this value. Similarly, qPCR-negative/antigen-positive discordant results were observed at lower antigenemia values, with the majority testing at <2 antigen-positive cells/slide (Figure 4b).

Figure 4. CMV qPCR by pp65 Antigenemia Results.

a) For the 95 samples with at least one positive CMV test, qPCR results were stratified according to their paired qualitative antigenemia results. Discordant results were not observed above qPCR values of 8500 ge/mL (line).

b) For the 95 samples with at least one positive CMV test, quantitative pp65 antigenemia results were stratified according to their paired qualitative qPCR results. The majority of discordant results occurred with antigenemia values of <2 antigen-positive cells/slide; however, one negative qPCR value had a paired antigenemia result of 62 antigen-positive cells/slide.

Clinical Covariates

To identify clinical factors associated with discordance, covariates were analyzed (Table 4). Of these, neutropenia (OR 3.55, 95% CI 1.10 - 11.44, p = 0.03), R+ CMV status (OR 2.16, 95% CI 1.03 - 4.53, p = 0.04) and antiviral treatment (OR 5.72, 95% CI 2.86 - 11.47, p <0.01) at the time of the paired tests increased odds of discordance. After multivariable analysis, only treatment remained significant (OR 4.33, 95% CI 2.00 – 9.38, p < 0.01), while neutropenia (p = 0.11) and R+ CMV status (p = 0.12) did not. There was no difference between oral valganciclovir and intravenous ganciclovir treatment regimens in the association with discordance (p = 0.64). Age (p = 0.71), concurrent antiviral prophylaxis (p = 0.19), and D+/R− status (p = 0.37) were not associated with discordant test results. Finally, time of test from transplant (p = 0.21) by month did not significantly affect odds of discordance. This factor was included to account for any changes in immunosuppression or prophylaxis that a patient would expect to undergo in the post-transplant course.

Table 4. Covariate Associations with Discordant Test Pairs for All Samples.

| Variable at Time of Test | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | P – value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.99 | 0.93 – 1.06 | 0.81 |

| D+ CMV Status | 1.96 | 0.91 – 4.20 | 0.08 |

| R+ CMV Status | 2.16 | 1.03 – 4.53 | 0.04 |

| D+/R− CMV Status | 1.37 | 0.69 – 2.74 | 0.37 |

| Antiviral Treatment ** | 5.72 | 2.86 – 11.47 | < 0.01 |

| Antiviral Prophylaxis | 0.60 | 0.28 – 1.30 | 0.20 |

| Time from Transplant (months) | 0.99 | 0.97 – 1.01 | 0.21 |

| Neutropenia (ANC <1000/mm3) | 3.55 | 1.10 – 11.44 | 0.03 |

| Female | 0.55 | 0.24 – 1.23 | 0.15 |

| Immune-mediated underlying renal disorder | 0.87 | 0.41 – 1.86 | 0.72 |

| Deceased Donor Graft Source | 1.79 | 0.87 – 3.70 | 0.11 |

Bold: Significant factors after multivariable adjustment

After multivariable analysis, only treatment remained significant (OR 4.33, 95% CI 2.00 – 9.38, p < 0.01), while neutropenia (p = 0.11) and R+ CMV status (p = 0.12) did not.

72.1% on valganciclovir, 27.9% on intravenous ganciclovir. The specific drug used did not significantly affect odds of discordance (OR 1.49, 95% CI 0.28 – 8.11, p = 0.64).

Groupings of discordant samples by type of discordance were next analyzed separately to identify factors uniquely related to qPCR-positive/antigen-negative and/or qPCR-negative/antigen-positive results (Table 5). Univariate analyses showed that antiviral treatment was associated with both qPCR-positive/antigen-negative samples (p = 0.01) and qPCR-negative/antigen-positive samples (p < 0.01) as compared to all other samples. While qPCR-negative/antigen-positive samples were also associated with neutropenia on univariate analyses (p = 0.01), subsequent multivariable analysis revealed that only treatment remained a significant factor (p = 0.02), while neutropenia did not (p = 0.10).

Table 5. Covariate Associations with Discordant Test Pairs for Restricted Sample Pools.

| qPCR-positive/antigen-negative Discordant Samples | qPCR-negative/antigen-positive Discordant Samples* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | P - value | OR | 95% CI | P - value |

| R+ CMV Status | 1.17 | 0.52 – 2.64 | 0.70 | 6.23 | 0.64 – 60.55 | 0.12 |

| Antiviral Treatment | 3.07 | 1.28 – 7.38 | 0.01 | 6.43 | 1.70 – 24.29 | < 0.01 |

| Neutropenia (ANC <1000/mm3) | 2.00 | 0.43 – 9.37 | 0.38 | 4.6 | 1.43 – 14.84 | 0.01 |

Bold: Significant factors after multivariable adjustment

After multivariable analysis accounting for both antiviral treatment and neutropenia, treatment remained a significant factor (OR 5.63, 95% CI 1.39 – 22.72, p = 0.02), while neutropenia did not (OR 3.10, 95% CI 0.82 – 11.74, p = 0.10).

Predictive Utility for Subsequent Tests

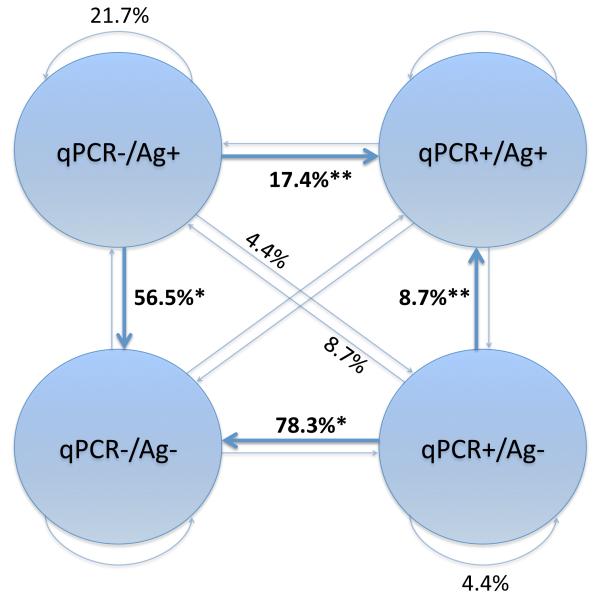

To investigate which of the two test results in a discordant pair might be more predictive of true CMV infection status, test results of the next consecutive sample following a discordant pair were analyzed. The likelihood of the next sample achieving a particular paired result from a given discordant pair is summarized in Figure 5. A qPCR-positive/antigen-negative discordant pair was no more likely to become concordantly positive on a subsequent test than was a qPCR-negative/antigen-positive (p = 0.47), even when restricting to those observations obtained while on treatment (p = 0.36). Similarly, a qPCR-positive/antigen-negative discordant pair was no more likely to become concordantly negative than was a qPCR-negative/antigen-positive result (p = 0.41, p = 0.90 on treatment).

Figure 5. Likelihood of Subsequent Concordant Results After a Discordant Result.

Lag-1 regression models were developed to determine if a discordant paired result provided predictive ability regarding subsequent pairs of tests. For these analyses, samples that were followed by another tested sample within the same individual were grouped together by specific paired results and are represented by circles (positive: +, negative: −, Ag: pp65 antigenemia). The proportions of discordant samples attaining a subsequent result are labeled (%).

*: No significant difference (p = 0.41) was observed between likelihoods of qPCR-negative/antigen-positive (56.5%) and qPCR-positive/antigen-negative (78.3%) discordant pairs becoming concordantly negative on the subsequent sample.

**: No significant difference (p = 0.47) was observed between likelihoods of qPCR-negative/antigen-positive (17.4%) and qPCR-positive/antigen-negative (8.7%) discordant pairs becoming concordantly positive on the subsequent sample.

Resolution on Treatment

Further analyses were performed on samples from subjects receiving antiviral treatment to determine if viral load by one assay cleared sooner than the other with treatment of infection. Of the 11 people who were treated for CMV infection, 9 were D+/R-, and all were observed to have at least one concordant qPCR-positive/antigen-positive sample. From these 11 subjects, there were 12 events where a concordant positive sample was followed by a sample with at least one negative test while on treatment (Table 6). For 7 of the 12 events, both antigenemia and qPCR resolved simultaneously. For 3 of the events, antigenemia resolved after qPCR with a range of 14 to 63 days difference. For 2 of the events, antigenemia resolved prior to qPCR with differences of 14 and 27 days. Due to the small number of these samples, only descriptive statistics could be used in this comparison.

Table 6. Resolution of CMV Positivity on Treatment from a Concordant Positive Result.

| Sequence of Resolution | Number of Events (n = 12) | Time Difference Range (days) |

|---|---|---|

| Simultaneous | 7 | 0 |

| qPCR First | 3 | 14 – 63 |

| Antigenemia First | 2 | 14 – 27 |

Detection of CMV Disease

Only two cases of CMV disease (1.7% of all patients) were diagnosed clinically, both in D+/R− patients off prophylaxis. The first was a 16 year-old D+/R− male who presented 6 months after transplant with fever, malaise, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and dehydration, 27 days after discontinuing valganciclovir prophylaxis. An initial CMV antigenemia test was positive (>100 cells/slide) and he soon developed an oxygen requirement with diffuse patchy infiltrates on chest x-ray. With no alternative etiology on subsequent work-up he was diagnosed clinically with CMV pneumonitis and gastrointestinal disease. Intravenous ganciclovir was initiated and paired tests on day 5 of antiviral therapy were positive with 2400 ge/mL by qPCR, and >100 positive cells/slide by antigenemia. Within 48 hours of treatment his fever and dyspnea had improved and abdominal pain resolved shortly thereafter. At day 7 of treatment his qPCR was negative, but his antigenemia remained positive at 62 positive cells/slide. He was treated for 21 days, at which time his antigenemia had decreased to 1 positive cell/slide, while qPCR remained negative. The antigenemia remained positive over 5 months later with no new or recurrent symptoms before finally becoming negative.

The second case was a 14 year-old D+/R− male who presented 1 year post-transplant with fever, dehydration, and a 2-week history of watery diarrhea and abdominal pain, having finished valganciclovir prophylaxis nearly 4 months prior. On admission he was positive for CMV by qPCR (48,300 ge/mL) and by antigenemia (>100 positive cells/slide). He was diagnosed with CMV colitis after alternative etiologies were excluded. He received intravenous ganciclovir for 5 days, after which he was switched to oral valganciclovir therapy due to marked clinical improvement. At a 3-week follow-up visit he was negative for CMV by both tests and his therapy was discontinued.

Due to the small number of cases observed, it was not possible to correlate assay results to disease outcomes or to establish definitive threshold values for preemptive therapy. Although both patients with disease had >100 positive cells by antigenemia, in this cohort 2 other patients had antigenemia values of >100 positive cells/slide (Figure 4b) but exhibited no symptoms of disease. Similarly, although disease was seen at qPCR levels as low as 2400 ge/mL in the second case, it is difficult to use this as a threshold value since the test was performed after initiation of antiviral therapy. Furthermore, some patients had no clinical disease despite qPCR values of up to 66,700 ge/mL (Figure 4a).

DISCUSSION

The pp65 antigenemia detection assay has long been used for preemptive monitoring of CMV infection in renal transplant patients. Despite its utility in rapid diagnosis of infection and lower cost (4-5 times less expensive per test at our center), the antigen-based assay has the disadvantages of needing to be performed within hours of collecting the blood sample and requiring operator expertise for optimal assay performance. Furthermore, it is not licensed as a quantitative test, though quantitative results are used clinically off-label to monitor infection. Quantitative PCR assays have offered an alternative method for rapid diagnosis of infection with objective, quantitative results. Although these two assays have been compared in adult transplant populations, this is the first study to evaluate paired assay results in an exclusively pediatric renal transplant population. This population is thought to be more vulnerable to the effects of disease due to a higher proportion of CMV naïve recipients, as well as concerns that younger children may be inherently more immunosuppressed than their adult counterparts (28). Young age itself is a risk factor for CMV infection independent of CMV D+/R− serostatus (30). Despite recent studies focusing on the pediatric population (30-36), standard protocols for CMV monitoring and administering antiviral therapies are not established (37).

In this study, comparison of paired qPCR and pp65-antigenemia tests showed that each assay performed comparably as shown by similar marginal rates of detection (positive tests) and strong overall agreement between assay results. The rate of infection (27.0%) in this study was comparable to other pediatric studies (24% – 35%), with most positive results occurring in the first 6 months after transplant (31-33, 35, 36). The proportion of positive samples obtained from patients on antiviral prophylaxis (29.5%) was also similar to those in previous reports (30% - 60%) (30, 31). Even after excluding samples from the 84 subjects who never tested positive due to concerns that these 474 negative results heavily weighted our findings towards higher agreement, the two assays still exhibited moderate agreement. The assays were also found to correlate well quantitatively, with the odds of concordance increasing at higher qPCR values, with no discordance observed above the threshold value of 8500 ge/mL. These results suggest that both assays are comparable in detecting CMV infection, and that either assay can be used for monitoring in pediatric renal transplant patients.

These results are consistent with previous studies in the adult solid organ and stem cell transplant populations that demonstrate good correlation between the two assays (13-16). The strength of correlation found in our study, κ = 0.61, lies within the range of similar analyses performed in other transplant populations (κ = 0.44 – 0.65) (17, 38, 39). Those findings suggest that qPCR assays can be used successfully in place of antigenemia assays, and our results support this conclusion in a pediatric population as well.

The discordant results were next analyzed for assay performance. Because qPCR has been shown to have greater sensitivity and lower specificity than pp65-antigenemia tests (40-42), it was initially anticipated that qPCR-positive/antigen-negative results would outnumber the opposite discordant qPCR-negative/antigen-positive results, as had been shown previously (20, 21, 39, 42). However, we observed similar numbers of qPCR-positive/antigen-negative discordant pairs (n = 27) and qPCR-negative/antigen-positive samples (n = 23) and found examples in the literature where the qPCR-negative/antigen-positive discordant type predominates (15, 16, 38). Our analyses showed that discordant results regardless of type are more likely to be observed at lower levels of viremia and from patients receiving antiviral treatment. This supports previous studies by Piiparinen et al. in which discordant results occurred most often in cases of low-level viremia and/or antiviral treatment (12, 15, 16), an observation that has since been repeated in a stem cell transplant population (38).

With discordant samples primarily occurring at low levels of viremia, we investigated whether the discordant samples represented an early signal of developing infection. The 5 discordant samples that preceded a concordant positive sample within 30 days were similarly split between qPCR-negative/antigen-positive and qPCR-positive/antigen-negative types, indicating that no one discordant positive was a better predictor for the development of a subsequent concordant positive sample. A separate analysis taking into account all 50 discordant samples regardless of timing confirmed the finding that one type was no more likely to be followed by a concordant positive sample than the other (p = 0.47). Despite the greater reported sensitivity of qPCR, this analysis did not demonstrate earlier positivity with qPCR compared to antigenemia.

Because treatment guidelines for CMV in transplantation now recommends therapy until obtaining negative samples (28), we analyzed the database to determine if one assay returned to negative sooner than the other while on treatment. Of the 12 events where a concordant positive sample was followed by a sample with at least one negative test while on treatment, qPCR and antigenemia resolved simultaneously for the majority of the time (7 events) whereas the remaining events were split relatively evenly between qPCR and antigenemia resolving first (2 vs. 3 events, respectively). Due to the small number of these events, no definite conclusions could be made regarding the time to resolution between assays, although these results suggest that either assay may be utilized to determine resolution of viremia.

Finally, despite having similar rates of infection with other pediatric populations, only 2 subjects in our cohort developed clinical CMV disease, both of whom were high-risk D+/R− patients off prophylaxis. Our incidence of symptomatic disease of 1.7% was lower than other reports in the pediatric literature (4.5% - 19.5%) (30-36). The low number of disease outcomes precluded attempts to correlate quantitative assay results with risk for CMV disease. A threshold for preemptive therapy to prevent disease also could not be determined, as asymptomatic subjects could have antigenemia values of >100 positive cells/slide and qPCR values of up to 66,700 ge/mL. Further study in a larger population may be helpful to define such threshold values for initiation of preemptive therapy.

Although all samples were collected prospectively according to established clinical protocol, the retrospective analysis was a limitation of this study. As samples were drawn from a variety of subjects at different points in their post-transplant course during the 2-year study period, we controlled for variations in post-transplant course by univariate analysis of duration from transplant to the time of the tests, which was not found to be a significant factor associated with discordance. Secondly, it is possible that these results have limited generalizability to other centers because of lack of standardization for CMV qPCR assays, a limitation that may soon be addressed by international standardization of clinical diagnostic CMV qPCR assays. Given the incidence of several instances where antigenemia was found to precede qPCR both in detection and resolution of CMV infection, future comparison of antigenemia with these standardized CMV qPCR assays may better assess their relative clinical utility.

In summary, qPCR and antigen-based assays for CMV performed comparably in detecting infection in a population of pediatric renal transplant recipients, and each may be utilized effectively in children. Discordant results were associated with low levels of viremia and concurrent antiviral treatment. There was no difference between the assays in predicting subsequent positive samples, or in the time to resolution of positivity while on treatment, suggesting that either test may be utilized effectively to monitor resolution of viremia during treatment in pediatric renal transplantation.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Cindy Richards RN, Renal Transplant Coordinator and Deidra Schmidt Pharm.D at Children's of Alabama, Penelope M. Jester, CASG Program Director, as well as Sonya Nix and Richard Covington of the UAB Pediatrics Diagnostic Virology Lab for their advice and support.

This work was supported by NIH5K08AI059428-02 (M.S.), the Children's Center for Research and Innovation of the Alabama Children's Hospital Foundation (M.S.), the Kaul Pediatric Research Initiative of The Children's Hospital of Alabama (M.S.); the UAB Collaborative Antiviral Study Group (DHHS/NIH/NIAID N01-AI-30025) (R.J.W.); and the UAB Infectious Diseases Training Grant (NIH 5 T32 AI052069) (B.R.). This work was presented in part at the Infectious Disease Society of America 48th Annual Meeting, the 2011 St. Jude/PIDS Pediatric Infectious Diseases Research Conference, and the 2011 American Transplant Congress.

Footnotes

The authors have no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Brian Rha, MD: Concept/design, Data collection, Data analysis/interpretation, Drafting article

David Redden, PhD: Data analysis/interpretation, Statistics, Approval of article

Mark Benfield, MD: Concept/design, Data collection, Approval of article

Fred Lakeman, PhD: Concept/design, Data collection, Approval of article

Richard J. Whitley, MD: Concept/design, Approval of article

Masako Shimamura, MD: Concept/design, Data analysis/interpretation, Critical revision of article, Approval of article

Rha B, Redden D, Benfield M, Lakeman F, Whitley RJ, Shimamura M. Correlation and Clinical Utility of pp65 Antigenemia and Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction Assays for Detection of Cytomegalovirus in Pediatric Renal Transplant Patients. Pediatr Transplantation.

REFERENCES

- 1.POTENA L, HOLWEG CT, CHIN C, et al. Acute rejection and cardiac allograft vascular disease is reduced by suppression of subclinical cytomegalovirus infection. Transplantation. 2006;82:398–405. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000229039.87735.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.REISCHIG T, JINDRA P, SVECOVA M, KORMUNDA S, OPATRNY K, JR., TRESKA V. The impact of cytomegalovirus disease and asymptomatic infection on acute renal allograft rejection. J Clin Virol. 2006;36:146–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2006.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.EVANS PC, SOIN A, WREGHITT TG, TAYLOR CJ, WIGHT DG, ALEXANDER GJ. An association between cytomegalovirus infection and chronic rejection after liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2000;69:30–35. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200001150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.SOLA R, DIAZ JM, GUIRADO L, et al. Significance of cytomegalovirus infection in renal transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2003;35:1753–1755. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(03)00715-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.SAGEDAL S, HARTMANN A, NORDAL KP, et al. Impact of early cytomegalovirus infection and disease on long-term recipient and kidney graft survival. Kidney Int. 2004;66:329–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.SAGEDAL S, NORDAL KP, HARTMANN A, et al. A prospective study of the natural course of cytomegalovirus infection and disease in renal allograft recipients. Transplantation. 2000;70:1166–1174. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200010270-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.SCHROEDER R, MICHELON T, FAGUNDES I, et al. Antigenemia for cytomegalovirus in renal transplantation: choosing a cutoff for the diagnosis criteria in cytomegalovirus disease. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:2781–2783. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.06.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.HUMAR A, GREGSON D, CALIENDO AM, et al. Clinical utility of quantitative cytomegalovirus viral load determination for predicting cytomegalovirus disease in liver transplant recipients. Transplantation. 1999;68:1305–1311. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199911150-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.EMERY VC, SABIN CA, COPE AV, GOR D, HASSAN-WALKER AF, GRIFFITHS PD. Application of viral-load kinetics to identify patients who develop cytomegalovirus disease after transplantation. Lancet. 2000;355:2032–2036. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02350-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.LIMAYE AP, HUANG ML, LEISENRING W, STENSLAND L, COREY L, BOECKH M. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) DNA load in plasma for the diagnosis of CMV disease before engraftment in hematopoietic stem-cell transplant recipients. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:377–382. doi: 10.1086/318089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.GOR D, SABIN C, PRENTICE HG, et al. Longitudinal fluctuations in cytomegalovirus load in bone marrow transplant patients: relationship between peak virus load, donor/recipient serostatus, acute GVHD and CMV disease. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1998;21:597–605. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.PIIPARINEN H, HOCKERSTEDT K, GRONHAGEN-RISKA C, LAUTENSCHLAGER I. Comparison of two quantitative CMV PCR tests, Cobas Amplicor CMV Monitor and TaqMan assay, and pp65-antigenemia assay in the determination of viral loads from peripheral blood of organ transplant patients. J Clin Virol. 2004;30:258–266. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2003.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.CALIENDO AM, ST GEORGE K, KAO SY, et al. Comparison of quantitative cytomegalovirus (CMV) PCR in plasma and CMV antigenemia assay: clinical utility of the prototype AMPLICOR CMV MONITOR test in transplant recipients. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:2122–2127. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.6.2122-2127.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.ROLLAG H, SAGEDAL S, KRISTIANSEN KI, et al. Cytomegalovirus DNA concentration in plasma predicts development of cytomegalovirus disease in kidney transplant recipients. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2002;8:431–434. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2002.00449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.PIIPARINEN H, HOCKERSTEDT K, GRONHAGEN-RISKA C, LAPPALAINEN M, SUNI J, LAUTENSCHLAGER I. Comparison of plasma polymerase chain reaction and pp65-antigenemia assay in the quantification of cytomegalovirus in liver and kidney transplant patients. J Clin Virol. 2001;22:111–116. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6532(01)00173-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.PIIPARINEN H, HELANTERA I, LAPPALAINEN M, et al. Quantitative PCR in the diagnosis of CMV infection and in the monitoring of viral load during the antiviral treatment in renal transplant patients. J Med Virol. 2005;76:367–372. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MARTIN-DAVILA P, FORTUN J, GUTIERREZ C, et al. Analysis of a quantitative PCR assay for CMV infection in liver transplant recipients: an intent to find the optimal cut-off value. J Clin Virol. 2005;33:138–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.SANGHAVI SK, ABU-ELMAGD K, KEIGHTLEY MC, et al. Relationship of cytomegalovirus load assessed by real-time PCR to pp65 antigenemia in organ transplant recipients. J Clin Virol. 2008;42:335–342. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2008.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.LILLERI D, BALDANTI F, GATTI M, et al. Clinically-based determination of safe DNAemia cutoff levels for preemptive therapy or human cytomegalovirus infections in solid organ and hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. J Med Virol. 2004;73:412–418. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.KALPOE JS, KROES AC, DE JONG MD, et al. Validation of clinical application of cytomegalovirus plasma DNA load measurement and definition of treatment criteria by analysis of correlation to antigen detection. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:1498–1504. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.4.1498-1504.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.KIM DJ, KIM SJ, PARK J, et al. Real-time PCR assay compared with antigenemia assay for detecting cytomegalovirus infection in kidney transplant recipients. Transplant Proc. 2007;39:1458–1460. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2007.01.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.PERES RM, COSTA CR, ANDRADE PD, et al. Surveillance of active human cytomegalovirus infection in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HLA sibling identical donor): search for optimal cutoff value by real-time PCR. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:147. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.GERNA G, BALDANTI F, TORSELLINI M, et al. Evaluation of cytomegalovirus DNAaemia versus pp65-antigenaemia cutoff for guiding preemptive therapy in transplant recipients: a randomized study. Antivir Ther. 2007;12:63–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.LILLERI D, GERNA G, FURIONE M, et al. Use of a DNAemia cut-off for monitoring human cytomegalovirus infection reduces the number of preemptively treated children and young adults receiving hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation compared with qualitative pp65 antigenemia. Blood. 2007;110:2757–2760. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-080820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.KANDA Y, YAMASHITA T, MORI T, et al. A randomized controlled trial of plasma real-time PCR and antigenemia assay for monitoring CMV infection after unrelated BMT. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010;45:1325–1332. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2009.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.SHAPIRO R, SARWAL MM. Pediatric kidney transplantation. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2010;57:393–400. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2010.01.016. table of contents. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.BRADFORD RD, CLOUD G, LAKEMAN AD, et al. Detection of cytomegalovirus (CMV) DNA by polymerase chain reaction is associated with hearing loss in newborns with symptomatic congenital CMV infection involving the central nervous system. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:227–233. doi: 10.1086/426456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.KOTTON CN, KUMAR D, CALIENDO AM, et al. International consensus guidelines on the management of cytomegalovirus in solid organ transplantation. Transplantation. 2010;89:779–795. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181cee42f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.HUMAR A, MICHAELS M. American Society of Transplantation recommendations for screening, monitoring and reporting of infectious complications in immunosuppression trials in recipients of organ transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:262–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.LAPIDUS-KROL E, SHAPIRO R, AMIR J, et al. The efficacy and safety of valganciclovir vs. oral ganciclovir in the prevention of symptomatic CMV infection in children after solid organ transplantation. Pediatr Transplant. 2010;14:753–760. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2010.01330.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.CAMACHO-GONZALEZ AF, GUTMAN J, HYMES LC, LEONG T, HILINSKI JA. 24 weeks of valganciclovir prophylaxis in children after renal transplantation: a 4-year experience. Transplantation. 2011;91:245–250. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181ffffd3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.MADAN RP, CAMPBELL AL, SHUST GF, et al. A hybrid strategy for the prevention of cytomegalovirus-related complications in pediatric liver transplantation recipients. Transplantation. 2009;87:1318–1324. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181a19cda. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DANZIGER-ISAKOV LA, WORLEY S, MICHAELS MG, et al. The risk, prevention, and outcome of cytomegalovirus after pediatric lung transplantation. Transplantation. 2009;87:1541–1548. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181a492e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.GREEN M, MICHAELS MG, KATZ BZ, et al. CMV-IVIG for prevention of Epstein Barr virus disease and posttransplant lymphoproliferative disease in pediatric liver transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:1906–1912. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.RENOULT E, CLERMONT MJ, PHAN V, BUTEAU C, ALFIERI C, TAPIERO B. Prevention of CMV disease in pediatric kidney transplant recipients: evaluation of pp67 NASBA-based preemptive ganciclovir therapy combined with CMV hyperimmune globulin prophylaxis in high-risk patients. Pediatr Transplant. 2008;12:420–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2007.00799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.YOON HS, LEE JH, CHOI ES, et al. Cytomegalovirus infection in children who underwent hematopoietic stem cell transplantation at a single center: a retrospective study of the risk factors. Pediatr Transplant. 2009;13:898–905. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2008.01084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.MARTIN JM, DANZIGER-ISAKOV LA. Cytomegalovirus risk, prevention, and management in pediatric solid organ transplantation. Pediatr Transplant. 2011;15:229–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2010.01454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.CHOI SM, LEE DG, LIM J, et al. Comparison of quantitative cytomegalovirus real-time PCR in whole blood and pp65 antigenemia assay: clinical utility of CMV real-time PCR in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. J Korean Med Sci. 2009;24:571–578. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2009.24.4.571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.HALFON P, BERGER P, KHIRI H, et al. Algorithm based on CMV kinetics DNA viral load for preemptive therapy initiation after hematopoietic cell transplantation. J Med Virol. 2011;83:490–495. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.TONG CY, CUEVAS L, WILLIAMS H, BAKRAN A. Use of laboratory assays to predict cytomegalovirus disease in renal transplant recipients. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2681–2685. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.9.2681-2685.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.HERNANDO S, FOLGUEIRA L, LUMBRERAS C, et al. Comparison of cytomegalovirus viral load measure by real-time PCR with pp65 antigenemia for the diagnosis of cytomegalovirus disease in solid organ transplant patients. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:4094–4096. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.10.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.XUE W, LIU H, YAN H, et al. Methodology for monitoring cytomegalovirus infection after renal transplantation. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2009;47:177–181. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2009.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]