Abstract

Bacteriophages T7, λ, P22, and P2/P4 (from Escherichia coli), as well as ϕ29 (from Bacillus subtilis), are among the best-studied bacterial viruses. This chapter summarizes published protein interaction data of intraviral protein interactions, as well as known phage–host protein interactions of these phages retrieved from the literature. We also review the published results of comprehensive protein interaction analyses of Pneumococcus phages Dp-1 and Cp-1, as well as coliphages λ and T7. For example, the ≈55 proteins encoded by the T7 genome are connected by ≈43 interactions with another ≈15 between the phage and its host. The chapter compiles published interactions for the well-studied phages λ (33 intra-phage/22 phage-host), P22 (38/9), P2/P4 (14/3), and ϕ29 (20/2). We discuss whether different interaction patterns reflect different phage lifestyles or whether they may be artifacts of sampling. Phages that infect the same host can interact with different host target proteins, as exemplified by E. coli phage λ and T7. Despite decades of intensive investigation, only a fraction of these phage interactomes are known. Technical limitations and a lack of depth in many studies explain the gaps in our knowledge. Strategies to complete current interactome maps are described. Although limited space precludes detailed overviews of phage molecular biology, this compilation will allow future studies to put interaction data into the context of phage biology.

I. INTRODUCTION

Bacteriophages have been extremely important model systems in molecular biology. They were critical to many breakthrough discoveries, such as the nature of the genetic material (Hershey, 1952), the structure of genes and genomes and the first genome sequence (Sanger et al., 1977), recombination (Kaiser and Jacob, 1957), transcriptional regulation (e.g., Roberts, 1969), and many others. In addition, phages have become important technical tools in molecular genetics and nanobiology, but these aspects are not reviewed here.

A great deal of work has been invested in learning the mechanistic details of the life cycles of a number of phages, including those described in this chapter. Although phages are tiny biological systems, surprisingly, not even the biology of main “model system phages” is completely understood. Despite a plethora of papers, few comprehensive summaries exist of the molecular interaction events that occur in both phage gene regulation and virion assembly. As in all organisms, protein–protein interactions (PPIs) play a fundamental role in phage biology. PPIs are important in all virus-related processes, including host infection, transcriptional regulation, DNA replication, virion assembly, and lysis. Current protein interaction databases (Lehne and Schlitt, 2009) have consistently neglected phage interactions. For instance, Intact, one of the most comprehenisve databases for protein–protein interactions, listed only 22 interactions for Caudovirales, the only phage group represented at the time of this writing (April 2011). We have thus attempted to compile such information for several phages that infect Gram-negative hosts, including λ, T7, P22, and P2/P4, as well as others that infect Gram-positive bacteria, specifically ϕ29, Dp-1, and Cp-1 (Table I). Coliphage T4 is one of the best understood of all the obligate lytic phages. T4 has been an outstanding model for phage biology, particularly for DNA replication, control of transcription, and virion assembly. Unfortunately, this chapter cannot discuss the extensive T4 PPIs here for reasons of space. Many of the small DNA phages, such as ϕX174 or M13, have been very well studied, but because of their tiny proteomes they do not have many protein–protein interactions. It would be highly desirable to establish their PPIs so that more comprehensive analyses of phage systems biology would be possible. Nevertheless, it is hoped that this chapter proves useful to the phage community and encourages similar compilations for other phages. The interactions collected for this chapter are available in Intact (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/intact/) for easy access.

TABLE I.

Summary of phage interactomes described in this chaptera

| Phage | Proteins | Phage–phage PPIs | Phage–host PPIs |

|---|---|---|---|

| T7 | 55 | ~43 (including 7 HTSb) | 15 |

| λ | 73 | 33 (+ 81 HTS) | 26 |

| P22 | 64 | 38 | 9 |

| P2/P4 | 42/13 | 14 | 3 |

| ϕ29 | 30 | 20 | 3 |

| Dp-1 | 72 | 156 (HTS) | 38 (HTS) |

| Cp-1 | 28 | 17 (HTS) | 11 (HTS) |

Note that all interactions from this chapter are available as a downloadable supplement from http://www.uetz.us.

High-throughput data (see text for details).

II. METHODS USED TO DETECT PROTEIN–PROTEIN INTERACTIONS

A. Genetic detection of interactions

Methods used to study protein–protein interactions in phages have evolved over the decades. A few important methods are illustrated in Figure 1. In the beginnings of phage molecular biology, detection of genetic interactions dominated. For instance, certain mutants in the λ J gene abolished virion binding to host Escherichia coli cells. Similarly, mutants of the E. coli gene lamB made the cells resistant to λ infections. From such experiments it was concluded that J protein bound to LamB and that LamB was the λ receptor. This hypothesis has been confirmed by isolating compensatory mutations in both genes that regenerate the interaction (Werts et al., 1994).

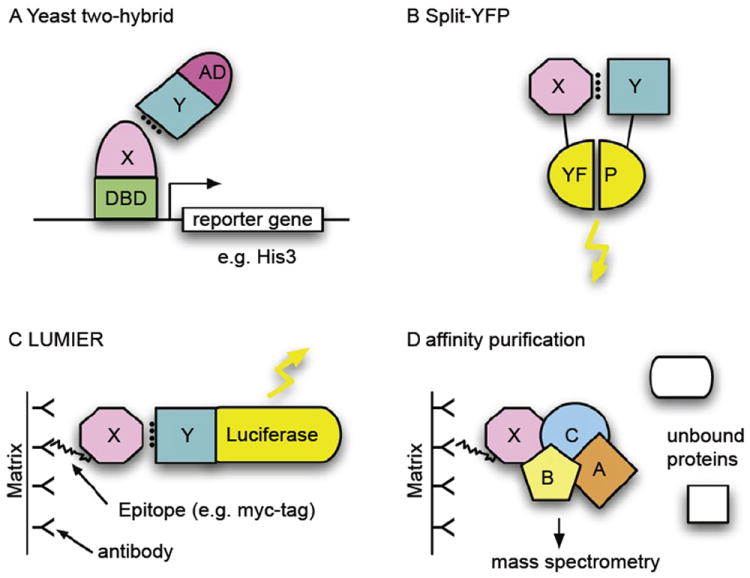

FIGURE 1.

Selected methods for the study of protein–protein interactions. (A) The yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) system is based on the levels of two fusion proteins (typically in yeast but any cell type can be used). One of the proteins contains a DNA-binding domain (DBD), which can bind to the promoter of a reporter gene (here: HIS3), and a second protein X, the bait. The second fusion protein consists of a transcription-activation domain (AD) and a second protein, Y. If proteins X and Y interact, a transcription factor is formed and the reporter gene is activated. In this case, that means that the cell can grow on histidine-free medium. A yeast colony growing on such medium thus indicates an interaction of the two inserted proteins. (B) Protein complementation assay (PCA), e.g., split-YFP. As in the Y2H assay, two interacting proteins bring together two protein fragments that are inactive when separate but active when in close proximity. Here, fragments of yellow-fluorescent protein (YFP) reassociate and fluoresce when reassembled. Other fluorescent proteins, such as the green fluorescent protein (GFP), have been used in a similar way. (C) LUMIER (LUMInescence-based mammalian intERactome). Two fusion proteins are purified by means of an epitope tag (here: FLAG tag), usually on an antibody-coated matrix. Interactions between X and Y can be detected using Luciferase, whose gene is fused to Y and which emits light when luciferin is added. (D) Affinity purification. Protein complexes can be purified from cellular lysates using an affinity epitope, as in (C) with a FLAG tag. Components of the complex can then be identified using mass spectrometry, using the unique mass of peptides when the protein is digested by trypsin.

B. Electron microscopy

Another important method for the investigation of physical relationships between phage components is electron microscopy, especially in combination with genetic analysis. Mutants often have an aberrant morphology. If certain structures are missing in the mutant virion, it can be concluded that the mutated gene encodes this structure or is at least involved in its assembly. For instance, many laboratory strains of λ harbor a frameshift mutation in the stf gene, and these mutants lack side tail fibers (Hendrix and Duda, 1992). Many such studies not only showed which genes encode which proteins, but also indicated how the proteins interact (e.g., when particular structures could be “removed” from the virion by defined gene knockouts).

More recently, many bacteriophage capsids and phage protein complexes have been analyzed by cryoelectron microscopy and three-dimensional reconstructions. This technique gives resolutions approaching that of X-ray crystallography, especially for proteins present in symmetric arrays in the virion, and has proven ideal for analyzing protein–protein interactions in large complexes, especially in combination with high-resolution structural data from other techniques, such as X-ray crystallography.

C. Yeast two-hybrid screens

More recently, the yeast two-hybrid system (Y2H) has become an important method to detect pairwise protein interactions. Interaction screens of phage proteins can be carried out easily by cloning all open reading frames in appropriate vectors and then testing these in a systematic pairwise fashion. This has been done for several phages, including coliphages T7 (Bartel et al., 1996) and λ (Rajagopala et al., 2011), as well as Streptococcus pneumoniae phages Cp-1 and Dp-1 (Häuser et al., 2011; Sabri et al., 2010). The whole process can also be automated.

One disadvantage of the Y2H system is that a typical pairwise screen, also called an “array screen” because of the systematic arrangement of clones in microtiter plates, may only detect 20–30% of all interactions. That is, the rate of false negatives is on the order of 70–80%. This can, in theory, be overcome by using multiple vectors that differ in the structure of the fusion proteins, for instance in the production of N- or C-terminal fusion proteins (Stellberger et al., 2010). A combination of multiple vectors can achieve interaction detection rates of up to 80% (i.e., false negative rates as low as 20%) (Chen et al., 2010).

Y2H also suffers from false positives that can only be understood with additional experimentation. Nonetheless, a multivector Y2H strategy can help in the recognition of false positives. For instance, if multiple vector combinations are used, interactions found in all or most cases are more likely to be “true positives,” whereas interactions detected in a lower fraction of cases are less reliable and may be false positives.

D. Protein complex purification and mass spectrometry

Whole phage virions can be purified, typically by CsCl density gradient centrifugation. Proteins from purified phage can then be denatured and separated on polyacrylamide gels or subjected directly to trypsin digestion and subsequent liquid chromatography (LC) and mass spectrometry (MS). The mass of peptides determined by MS can usually identify the corresponding proteins unambiguously, and thus composition of the phage particles. Once all proteins in a virion are identified, at least some can be assigned easily to known structures, such as the icosahedral capsid or tail sheath. Typically, only a fraction of all phage-encoded proteins are represented in the mature virion (e.g., less than 20 of the ≈70 phage λ proteins). Especially for little-studied phages it can be extremely helpful to know which proteins are in the virion. For example, in an analysis of Streptococcus phage Dp-1, only 8 of the 72 predicted proteins were identified by LC/MS and were thus confirmed structural proteins (see later).

E. Biochemistry of protein complexes

Biochemical approaches often involve the purification of protein complexes and thus yield protein interaction information. This approach can be made technically easier if individual proteins are affinity tagged. For instance, phage-encoded proteins can often be fused to affinity column-binding proteins such as glutathione-S-transferase or oligohistidine without affecting their function. Such tagged proteins and proteins bound to them can then be purified using affinity reagents. The untagged proteins in the complex can then be identified by mass spectrometry or immunoblotting (if antibodies against specific proteins are available). A range of experimental techniques is available for the characterization of phage protein complexes and their activities; a comprehensive overview cannot be given here. For instance, chemical cross-linking of interacting proteins is used frequently to spatially locate physically associated proteins, and variable spacer lengths can determine the steric proximity of the binding partners. Other tests include activity assays (e.g., proteases or other modifying enzymes that may be required for phage assembly), replication, or other processes. Some examples of such activities are described here.

F. X-ray crystallography and nuclear magnetic resonance

Only atomic structures of all phage proteins and their interactions will give a mechanistic understanding of phage biology, and progress in this area has been accelerating. Individual proteins and protein complexes, if not the whole phage particle, can be crystallized and the structure of such proteins solved by X-ray analysis. Alternatively, protein structures can be solved by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) if high enough concentrations can be achieved. Unfortunately, size restrictions on NMR structural determinations limit the analysis of large protein complexes, but monomeric structures can be extremely useful in devising testable models for the interactions proteins may undergo. However, many phage proteins are refractory to structural analysis (especially those involved in virion assembly, as they often assemble only at high concentrations), and even in classical model systems such as phage λ less than a third of all phage-encoded proteins have been crystallized—most of these as pure proteins rather than as protein complexes (Rajagopala et al., 2011;Yura et al., 2006).

III. PROTEIN–PROTEIN INTERACTIONS OF BACTERIOPHAGES

A. Coliphage T7

Bacteriophage T7 was defined in 1945 as a member of the seven Type (“T”) phages that grow lytically on E. coli B (Demerec and Fano, 1945), although it is probably identical to phage δ, used earlier by Delbrück; a close relative of T7 was likely studied by d’Herelle in the 1920s (d’Herelle, 1926). Relatives of T7 exhibit high synteny across their entire genomes, with the closest relatives differing primarily only by the number and location of homing endonucleases or other selfish elements not known to have any role in phage development. These phages therefore will exhibit life cycles and PPIs that parallel T7 itself, modified only by the resources available in their host organisms.

1. Growth physiology

T7 grows on rough strains of E. coli (i.e., those without full-length O-antigen polysaccharide on their surface) and some other enteric bacteria, but close relatives have been described that infect smooth and even capsulated strains (Molineux, 2006a). In such phages, tail fibers present on T7 are replaced with tailspikes with enzymatic activity that degrades the O- or K-antigens on the cell surface. T7 has a short latent period of 17 min at 37°C, which has resulted in most physiological studies being conducted at 30°C where infected cells lyse after 30 min. However, adaptation of T7 to high fitness with an excess of an E. coli K-12 strain growing under optimal conditions at 37°C in rich media results in a phage with a latent period of only ≈11 min. This adapted phage can undergo an effective expansion of its population by more than 1013 in 1 hr of growth (Heineman and Bull, 2007). There is no obvious subtlety in the T7 developmental pathway: the early region of its genome is transcribed efficiently by the host RNA polymerase, leading to synthesis of a phage-specific RNA polymerase and the concurrent inhibition of the host enzyme. Thus, T7 rapidly takes control of the transcriptional capacity of the infected cell. As E. coli mRNAs are also intrinsically unstable, T7 therefore also gains control of the translational capacity of the cell. Further, because T7 uses nucleotides derived from the host chromosome for its own replication, more than 80% of the DNA in progeny is derived from the bacterial chromosome and only a small burst is observed after infection of DNA-free minicells. T7 development is not known to be dependent on host chaperones, although it does code for two proteins that have been suggested to have chaperone activity in capsid and tail assembly. Aside from host components used for phage adsorption, plus general biosynthetic processes and the translational apparatus, T7 development is remarkably independent of host proteins: only E. coli RNA polymerase, thioredoxin—the cofactor for T7 DNA polymerase—and (deoxy)cytidine monophosphate kinase are known to be essential.

2. Early steps in infection

T7 is a member of Podoviridae, possessing only a short stubby tail that needs to be extended functionally in order to span the cell envelope, which thus allows its genome to be translocated into the cell. Tail extension is affected through internal head proteins that are ejected into the cell at the initiation of infection prior to or concomitant with transport of the leading end of the genome (Chang et al., 2010; Kemp et al., 2005). A schematic of the T7 virion is shown in Figure 2. In T7, the core consists of several copies each of three proteins (gp14, gp15, and gp16), which must interact, albeit perhaps loosely, with themselves and each other, in the phage capsid. However, during their ejection into the cell they must at least partially dissociate and also partially unfold in order to pass through the narrow channel through the portal and tail (Molineux, 2006b). The N-terminal domain of gp16 refolds spontaneously in the periplasm of the infected cell to form an enzyme with lytic transglycosylase activity (Moak and Molineux, 2000, 2004). This muralytic activity is only conditionally essential for T7 infection (Moak and Molineux, 2000).

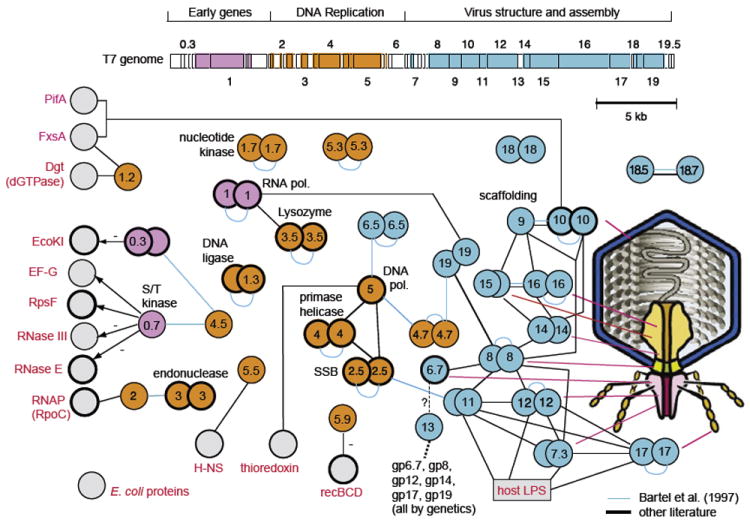

FIGURE 2.

Phage T7: genome, virion, and interactome. ORFeome and protein interaction map of bacteriophage T7. Cloned open reading frames (ORFs) and random fragments were used to generate a two-dimensional interaction map. ORFeomes can also be used by structural genomics projects to derive three-dimensional structures. A combination of interaction maps and crystal structures often allows reconstruction of protein complexes as in viral particles or their subunits. (Top) T7 genome with each ORF represented as a box. ORFs indicated by integral numbers were identified originally as essential by genetic screens. Other genes have decimal numbers; of these, only 2.5 and 7.3 are essential. Proteins found to interact with other proteins are indicated by colored boxes; colors indicate a simplified assignment to functional classes as shown. Interactions between proteins are shown as lines, with self-interactions shown as dimers. Hatched lines indicate expected interactions that have not been found by two-hybrid analysis. Gray proteins correspond to host proteins (E. coli). Blue proteins are involved in virus assembly and structure, and, where known, their location in the virus particle is shown on the right. Proteins with thick borders have been crystallized and their structure determined. Genetic map modified after Dunn and Studier (1983). Figure modified after Uetz et al. (2004). Interactions based primarily on data in Table II (see references therein).

The C-terminal residues of gp16, likely together with a more central portion of gp15, also refold in the periplasm and then insert spontaneously into the cytoplasmic membrane, completing the channel across the cell envelope for DNA translocation into the cell. Likely the last of the core proteins to exit the phage head, gp14 is found exclusively within the outer membrane of the infected cell. Using energy derived from the membrane potential, these proteins then ratchet the leading 1 kb of the T7 genome into the cell (Chang et al., 2010; Kemp et al., 2005). In both T7 and T3, genome internalization by this process stops, and the remainder of the DNA is normally pulled into the cytoplasm as a consequence of host and then phage RNA polymerase-catalyzed transcription (Garcia and Molineux, 1995, 1996; Kemp et al., 2004). Several strong promoters lie on this leading 1-kb segment of the T7 genome.

3. Early genes

Transcription from T7 early promoters not only internalizes the remainder of the genome but also leads to expression of early T7 genes, some of which interact and inhibit or modulate the activity of host proteins (Molineux, 2006a). Of the early proteins, only T7 RNA polymerase is essential for phage growth. The first T7 protein to be synthesized is gp0.3, an anti-type I restriction protein (Studier, 1975). The structure of gp0.3 reveals that it resembles double-stranded DNA, and the protein binds to the specificity subunit of the heteropentameric EcoKI enzyme, preventing both it and the cognate modification enzyme from recognizing its target sequence (Atanasiu et al., 2001, 2002; Kennaway et al., 2009; Murray, 2000; Stephanou et al., 2009). T7 gp0.3 is active against all type I enzymes and thus T7 grows normally on B, C, and K-12 strains of E. coli regardless of its previous host. However, the protein affords no protection against type II and little, if any, against type III enzymes. Gp0.3 proteins of different T7-like phages fall into two distinct groups with no sequence similarity; both have anti-restriction activity but the group typified by T3 gp0.3 also has SAMase activity (Studier and Movva, 1976). The second major early protein whose function is known is gp0.7, a serine-threonine kinase (Rahmsdorf et al., 1974) that is also responsible for the shut off of host transcription. The two activities are separable (Simon and Studier, 1973). Gp0.7 phosphorylates several host proteins, including RNA polymerase (Severinova and Severinov, 2006; Zillig et al., 1975), the translational apparatus including EF-G and the small ribosomal subunit protein S6 (Robertson and Nicholson, 1990, 1992; Robertson et al., 1994), and both RNase III (Marchand et al., 2001) and RNase E (Mayer and Schweiger, 1983). T7 shuts down translation of host mRNAs but it remains unclear whether EF-G or S6 is involved directly. An unknown T7 late gene also modulates the specificity of RNase E (Savalia et al., 2010). Although it is likely that others do so, only 1 other of the 10 early T7 proteins is currently known to interact with host proteins. Gp1.2 binds to E. coli dGTPase, converting it into a rGTP-binding protein (Huber et al., 1988; Nakai and Richardson, 1990); gp1.2 also binds to the membrane protein FxsA and the F plasmid protein PifA (Cheng et al., 2004; Schmitt and Molineux, 1991; Wang et al., 1999).

4. T7 RNA polymerase

The hallmark of T7 is of course its phage-encoded RNA polymerase, which, together with its regulator T7 lysozyme, is responsible for most T7 gene expression. It is also essential for synthesizing RNA primers at the primary origin of replication (Fujiyama et al., 1981) and for initiation of DNA packaging (Zhang and Studier, 1997, 2004). In addition to several complexes containing a promoter and product RNAs (Cheetham and Steitz, 1999; Cheetham et al., 1999; Kennedy et al., 2007; Tahirov et al., 2002; Yin and Steitz, 2002, 2004), the crystal structure of the RNA polymerase–lysozyme complex has been determined (Jeruzalmi and Steitz, 1998). Many mutants in both RNA polymerase and lysozyme have been characterized that affect their functional interaction, but it is not obvious from the crystal structures how the mutations affect the regulation of transcription. Lysozyme is thought to target the initial transcribing complex in a promoter strength-dependent manner and have no effect on transcription elongation (Huang et al., 1999; Stano and Patel, 2004; Zhang and Studier, 1997, 2004). Lysozyme is, however, important in pausing or terminating transcription at the class II terminator CJ, where it probably interacts directly with the T7 terminase protein gp19 and thus directs the packaging machinery to create the DNA terminus (Lyakhov et al., 1997, 1998; Zhang and Studier, 2004).

After T7 RNA polymerase has been synthesized, there is no further requirement for the host polymerase and it actually becomes inhibitory to phage development. Inactivation is caused by the T7 gp2 protein, which binds to the β′ subunit and inhibits transcription by interfering with strand separation of the open complex at most promoters (Camara et al., 2010; Nechaev and Severinov, 1999). In vivo, the only T7 promoter that must be inhibited by gp2 is A3 (Savalia et al., 2010). Gp2 was found to interact with T7 endonuclease gp3 by a yeast two-hybrid screen (Bartel et al., 1996). An interaction between gp2 and gp3 (albeit not necessarily direct) was suggested earlier (Mooney et al., 1980), but the idea has not yet been critically evaluated experimentally.

5. DNA replication

T7 has been one of the primary model systems for understanding the biochemistry of DNA replication. Central to T7 replication is T7 DNA polymerase, which comprises a heterodimer of gp5 and the host thioredoxin. Binding of gp5 to thioredoxin is strong, with the latter serving as the processivity factor for DNA replication, increasing the length of DNA synthesized per binding event 100-fold. The interface between the two proteins also provides the docking site for binding of the other two proteins, SSB (gp2.5) and the primase–helicase gp4, which are central to T7 replication in vivo. The process of T7 replication in vitro has been reviewed recently (Hamdan and Richardson, 2009).

Two other proteins in the DNA replication cluster are known to interact with host proteins. The gene 5.5 product binds to the abundant nucleoid-associated protein H-NS (Ali et al., 2011) and in vitro relieves its inhibition of both E. coli and T7 RNA polymerase-catalyzed transcription (Studier, 1981). In vivo, T7 5.5 mutants direct reduced rates of DNA replication and exhibit a small plaque phenotype (Lin, 1992; Liu and Richardson, 1993; Studier, 1981). However, the phenotype persists in hns-defective strains, although an hns mutant that renders gene 5.5 essential has been isolated (Liu and Richardson, 1993). Gp5.5 also interacts with the λ proteins of RexAB system; it is not known whether this is a direct protein–protein interaction or whether gp5.5 interacts with a product of RexAB activity. A gene 5.5 missense, but not a null mutant, makes T7 sensitive to Rex-mediated exclusion. The product of gene 5.9 inhibits the E. coli RecBCD nuclease in a comparable manner to λ Gam protein; this interaction is also nonessential as mutants lacking gene 5.9 grow normally in rec(BCD)+ hosts (Lin, 1992).

The assembly of T7 virions involves several symmetry mismatches and many protein–protein interactions, some of which may be helped by other T7 proteins that potentially have a chaperone-like activity (Kemp et al., 2005). Note that, GenBank annotations notwithstanding, gp13 is not a structural component of the virion (Kemp et al., 2005). Assembly is thought to initiate with oligomerization of the portal protein gp8 to form a dodecameric ring, although both 12- and 13-mers are observed following overexpression of gene 8 (Cerritelli and Studier, 1996b; Kemp et al., 2005; Valpuesta et al., 1992, 2000). The pathway of prohead formation may then involve assembly of the internal core (gp14, gp15, and gp16) on the inner surface of the portal, perhaps concomitant with the recruitment of capsid protein gp10 hexamers bound to scaffolding protein gp9. Subsequent recruitment of gp10 pentamers and hexamers results in shell formation around a scaffold of gp9 (Cerritelli et al., 2003a). The 12-fold symmetrical portal protein faces a symmetry mismatch with the 5-fold vertex of the icosahedral capsid shell. The internal core of T7 contains 4 copies of gp16, 8 copies of gp15, and either 10 or 12 copies of gp14 (Agirrezabala et al., 2007; Cerritelli et al., 2003b; Kemp et al., 2005). These proteins are ejected into the infected cell in order to transport the phage genome into the cytoplasm, and the protein–protein interactions in the mature virion are likely quite different than those found in the infected cell. Gp14 lies at the base of the internal core and is therefore juxtaposed to the 12-fold symmetrical portal protein. Complicating our understanding of the T7 virion is the identification of ≈18 copies of the small gp6.7 protein, which is ejected into the outer membrane of the infected cell at the initiation of infection (Kemp et al., 2005). It is not known where gp6.7 is located; it likely forms part of the internal core or lies within the portal channel.

6. Tail

The outer face of the portal is the site of assembly of the sixfold symmetrical stubby tail. The tail is composed of three proteins—gp7.3, 11 and 12—to which six trimers of the tail fiber protein gp17 are attached. Each trimer consists of three domains: an N-terminal third that binds to the tail; this domain is conserved in phages related to T7 that have a different host range. This domain is followed by a triple-stranded coiled-coil of ≈120 residues and then a C-terminal half consisting of globular domains that interacts with the cell surface lipopolysaccharide (Steven et al., 1988). The body of the tail consists of 12 copies of gp11, 6 copies of gp12, and ≈30 copies of the small protein gp7.3 (Kemp et al., 2005). How these proteins are arranged is unknown. It has been suggested that gp7.3 functions as a tail assembly protein that remains with the mature virion; the protein is ejected into the outer membrane of the infected cell (Chang et al., 2010; Kemp et al, 2005). Host range mutants of T7 suggest that all three proteins interact directly with the lipopolysaccharide of the host cell.

7. Interactome screening

T7 was the focus of the first genome-wide screen for phage protein–protein interactions using the yeast two-hybrid assay (Bartel et al., 1996). As proof of principle, T7 was a good choice: the extensive genetic, molecular biology, and biochemical studies that had been performed on T7 provided a solid basis for evaluating the accuracy and completeness of the approach. Twenty-five interactions were identified in the screen, 15 of which were intramolecular. Many of these are to be expected as even monomeric polypeptides fold into a three-dimensional structure. Virion assembly clearly involves extensive protein–protein interactions, but as discussed by the authors, many of those that were known or plausibly expected from known structures were missed in the screen (Bartel et al., 1996). Conversely, screen-predicted interactions involving gp1.7 that were confirmed subsequently by its purification as an oligomer (Tran et al., 2010) and the predicted interactions between the spanin proteins gp18.5 and gp18.7 predated the discovery of a heterodimer even in phage λ (Casjens et al., 1989). Six intermolecular interactions were predicted that have not yet found confirmatory support, and our current understanding of T7 suggests that some are implausible. Improved screening procedures should help resolve these outstanding issues and, if more intermolecular interactions can be found that are consistent with, in particular, the pathways of virion assembly, the utility of those screening procedures in predicting the protein interactome of lesser-studied phages will be enhanced greatly. All published T7 interactions are summarized in Table II.

TABLE II.

Protein–protein interactions of phage T7

B. Coliphage λ

Phage λ may be the best-studied temperate phage and has been under investigation since the early 1950s. There are probably thousands of papers that have been published on phage λ and its closer relatives N15, HK97, and P22. For instance, there are more than 400 citations in a review of lambdoid phages that do not even focus on the genetic switch of λ, the paradigm for gene regulation (Hendrix and Casjens, 2006). The switch has been described in detail by many other papers and in its own book (Court et al., 2007; Ptashne, 2004). This section summarizes current knowledge of the interactions among phage λ proteins. Finally, a summary of interactions with its host, E. coli, is given. For a more detailed description of phage λ biology and regulation, the authors refer the reader to other reviews (Calendar, 2006; Court et al. 2007; Hendrix and Casjens, 2006; Hendrix et al., 1983; Oppenheim et al., 2005; Ptashne, 2004).

1. The λ virion

The phage λ genome and virion are shown in Figure 3. Note that the virion contains tail fibers that are not visible in most λ micrographs. The variant of λ used in most laboratories around the world, λPaPa, has a frameshift mutation in the structural stf gene and lacks the long “side tail fibers” of λ, Ur-λ, that comes directly from the original E. coli K-12 lysogen. It is still not entirely clear how many different proteins are in the λ particle but 12 are known with confidence and 2 more (gpM and gpL) are possibly in the particle in very low numbers. A current model of the particle with its known proteins is shown in Figure 3. Based on this model, we can predict at least 23 PPIs in the virion (Table III), although several are inferred from genetic experiments and remain to be detected by biochemical or biophysical methods. The virion adsorbs to sensitive cells through an interaction between the tail tip protein gpJ and the host LamB outer membrane protein. DNA is then released through the tail into the cytoplasm.

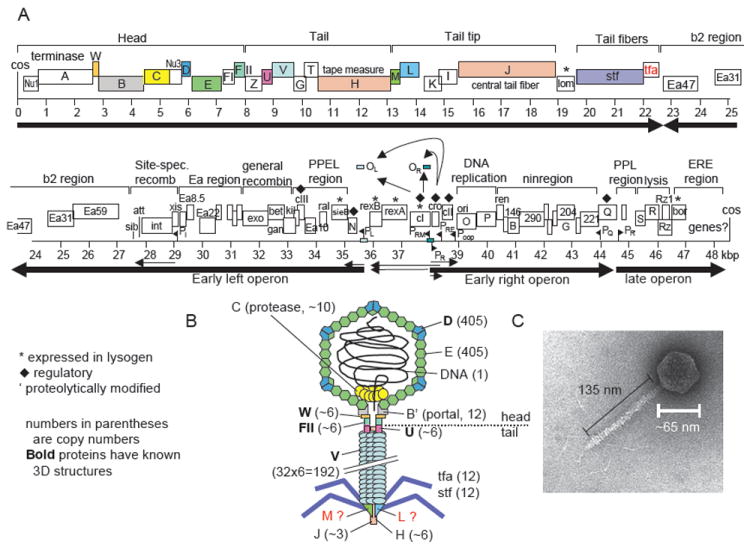

FIGURE 3.

Genome and virion of phage λ. (A) Genome of phage λ. Colored ORFs correspond to colored proteins in (B). Main transcripts are shown as arrows. After Hendrix and Casjens in Calendar (2006). (B) Schematic model of λ virion. Numbers indicate the number of protein copies in the particle. It is unclear whether gpM and gpL proteins are in the final particle or only required for assembly. (C) Electron micrograph of phage λ. Modified after Hendrix and Casjens (2006).

TABLE III.

Published protein–protein interactions of phage λ

| λ 1 | λ 2 | Notes | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| gpA | gpNu1 | gpA (N-terminal) – gpNu1 (C-terminal) | Catalano, 2000; de Beer et al., 2002; Hang et al., 1999 |

| gpA | gpB | gpA (C-terminal) – gpB (= portal) | Catalano, 2000; Duffy and Feiss, 2002 |

| gpW | gpB | gpW (NMR, head–tail joining) | Casjens, 1974; Casjens et al., 1972 |

| gpW | gpFII | gpW required for gpFII binding | Casjens, 1974; Maxwell et al., 2001 |

| gpB | gpB | 12-mer (22 amino acids removed from gpB N-terminal) | Kochan, Carrascosa and Murialdo, 1984; Tsui and Hendrix, 1980 |

| gpC | gpE | Covalent PPI (in virion?) | Hendrix and Casjens, 1974;Hendrix and Duda, 1998 |

| gpC′ | gpB | Murialdo, 1979 | |

| gpC | gpNu3 | gpC may degrade gpNu3 (before DNA packaging) | Hendrix and Casjens, 1975; Hohn et al., 1975; Medina et al., 2010; Murialdo and Becker, 1978 |

| gpD | gpD | gpD forms trimers | Mikawa et al., 1996; Sternberg and Hoess, 1995; Yang et al., 2000 |

| gpE | gpE | Major capsid protein | Casjens and Hendrix, 1974; Dokland and Murialdo, 1993; Lander et al., 2008 |

| gpU | gpU | “Probably a hexamer” | Katsura and Tsugita, 1977 |

| gpD | gpE | Casjens and Hendrix, 1974; Dokland and Murialdo, 1993; Lander et al., 2008 | |

| gpU | gpV | gpU is head-proximal tail protein | Pell et al., 2009 |

| gpV | gpV | Buchwald et al., 1970a,b; Casjens and Hendrix, 1974; Katsura, 1983 | |

| gpO | gpP | Wickner and Zahn, 1986; Zahn and Blattner, 1985, 1987; Zahn and Landy, 1996) | |

| gpO | gpO | gpO–gpO interactions when bound to ori DNA | Alfano and McMacken, 1989 |

| gpB | gpA | Genetic evidence | Frackman et al., 1985; Sippy and Feiss, 1992 |

| gpFI | gpA | Genetic evidence | Catalano and Tomka, 1995 |

| gpFI | gpE | Genetic evidence | Murialdo and Tzamtzis, 1997 |

| gpH | gpG/gpGT | gpG/gpGT holds gpH in an extended fashion | Hendrix and Casjens, 2006 |

| gpV | gpGT | T domain binds soluble gpV | Hendrix and Casjens, 2006 |

| gpH | gpV | gpV probably assembles around gpH, displacing gpG/gpGT | Xu et al., 2004 |

| CI | CI | Forms octamer that links OR to OL | Bell and Lewis, 2001; Dodd et al., 2001 |

| Exo | Bet | Radding et al., 1971 | |

| SieB | Esc | Esc is encoded in frame in SieB and inhbits SieB | Ranade and Poteete, 1993a,b |

| CII | CII | Homotetramers | Ho and Rosenberg, 1982 |

| Xis | Int | Sam et al., 2002 | |

| Xis | Xis | Xis-Xis binding mediates cooperative DNA binding | Sam et al., 2004 |

| Int | Int | Dimer | Warren et al., 2003 |

| Stf | Stf | Likely homotrimer by homology with T4 fibers | |

| gpS | gpS | Large ring in inner membrane | Savva et al., 2008 |

| gpS | gpS′ | gpS′ inhibits gpS ring formation | Grundling et al., 2000 |

| gpB | gpE | Copurify in procapsid | Hendrix and Casjens, 1975 |

| gpNu3 | pNu3 | Monomer–dimer equilibrium | C. Catalano, personal communication |

| CIII | CIII | Dimer | Halder et al., 2007 |

| Cro | Cro | Dimer; X-ray str | Anderson et al., 1979 |

| gpRz | gpRz1 | Heteromultimer supposed to span the periplasm | Summer et al., 2007 |

| gpNu3 | gpB | gpNu3 required for gpB incorporation into procapsid | Ray and Murialdo, 1975 |

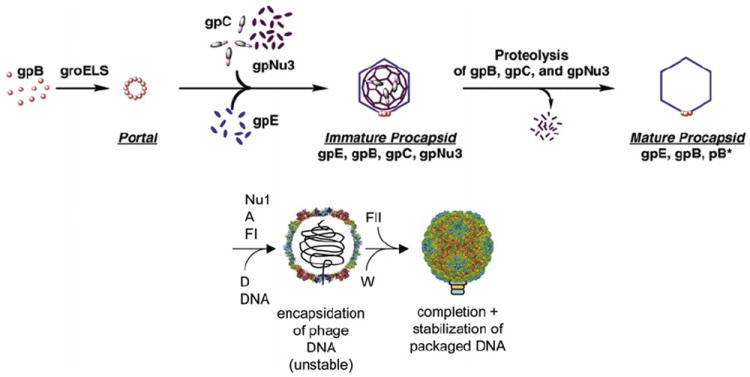

2. Assembly of virion head (Fig. 4)

FIGURE 4.

Assembly of the phage λ head. Head assembly has been subdivided into five steps, although most steps are not very well understood in mechanistic terms. Note that the tail is assembled independently. GpC protease, scaffolding protein gpNu3, and portal protein gpB form an ill-defined initiator structure. Protein gpE joins this complex in a step requiring the chaperonins GroES and GroEL. Proteins gpNu1, gpA, and gpFI are required for DNA packaging. GpD joins and stabilizes the capsid as a structural protein; gpFII and gpW are connecting the head to the tail that joins once the head is completed. Modified after Georgopoulos et al. (1983) and Lander et al. (2008).

λ encodes 10 proteins required for head assembly, of which 6 end up in the mature virion. Head assembly starts with assembly of the portal, which requires the host GroEL/S chaperone for folding. It is thought that the portal serves as the nucleus for assembling the remaining capsid. However, the mechanistic details of assembly are not well understood. GpC is involved as a head maturation protease that becomes attached covalently to E, the main capsid protein. The resulting fusion proteins subsequently get trimmed to make slightly shortened products named X1 and X2 (Hendrix and Casjens, 1974). The authors note, however, that attempts to identify X1 and X2 were unsuccessful and thus X1 and X2 may be artifacts (Medina et al., 2010). GpNu3 acts as putative scaffolding protein that aids coat shell assembly and is removed from the capsid by proteolysis before DNA is packaged. Structures of the procapsid and mature λ capsid have been solved by cryo-EM, showing the T=7 arrangement of capsid protein gpE clustered into hexamers and pentamers (Dokland and Murialdo; Lander et al., 2008). Trimers of the decoration protein gpD bind to the capsid at trivalent interaction points between the capsomers and stabilize the capsid (Sternberg and Weisberg, 1977). Comparison of the procapsid with the mature capsid reveals the considerable structural transitions that occur upon capsid maturation and DNA packaging, but this process is not well understood mechanistically.

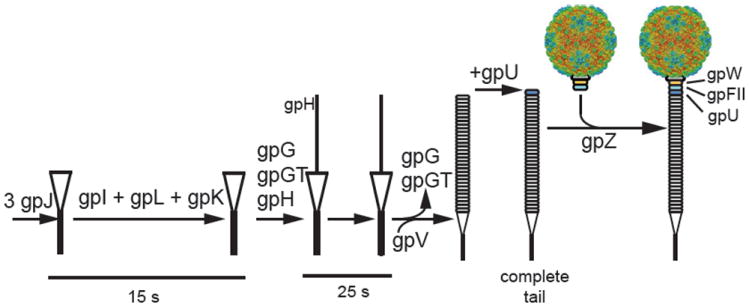

3. Assembly of virion tail (Fig. 5)

FIGURE 5.

Assembly of the phage λ tail. The λ tail is made of at least six proteins (gpU, V, J, H, tfa, stf) with another seven required for assembly (gpI, M, L, K, G/T, Z). Assembly starts with protein gpJ, which then, in a poorly characterized fashion, requires proteins gpI, gpL, gpK, and gpG/T to add the tape measure protein H. GpM joins and then gpG and gpG/T leave the complex so that the main tail protein gpV can assemble on the gpJ/H scaffold. Finally, gpU is added to the head-proximal end of the tail. GpZ is required to connect the tail to the preassembled head. Protein gpH is cleaved by the action of gpU and gpZ (Tsui and Hendrix, 1983). It remains unclear if proteins gpM and gpL are part of the final particle (Hendrix and Casjens, 2006). From http://www.pitt.edu/~duda/lambdatail.html.

Tail assembly begins with the antireceptor protein gpJ. Proteins gpI, gpK, gpL, and gpM assemble around gpJ in that order, although no mechanistic or structural details are known about this process. In parallel events, gpH, gpG, and gpG-T (the frameshifted form of gpG including the T reading frame) form a complex that binds the tail tip and the major tail protein (gpV). The tape meassure protein gpH determines the length of the phage tail (Katsura, 1990). Once the correct length is achieved, gpV assembly stops and the proximal tail protein gpU is added. Protein gpZ somehow facilitates head–tail joining without being assembled into the final virion.

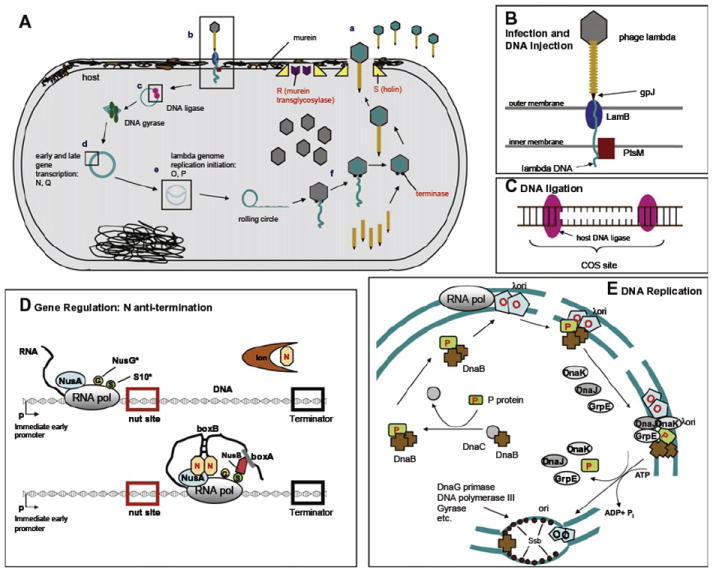

4. Lysogeny and induction

After phage DNA ejection, circularization, and ligation by the host DNA ligase, the earliest genes to be expressed include N, O, and P, as well as cII and cIII, which play a key role in the lysis/lysogeny decision (Echols, 1986). Both CII and CIII can interact with and be cleaved by the bacterial FtsH (HflB) protease directly, which in turn is complexed with the host HflK and HflC proteins at the cytoplasmic membrane. HflD, a cytoplasmic membrane protein, also binds CII, making it both more susceptible to FtsH and less able to bind DNA (Kihara et al., 2001; Parua et al., 2010). As a substrate for FtsH, CIII acts as a competitive inhibitor of CII degradation and, as the half-life of CII protein increases, leads to an increase in CI repressor synthesis (Datta et al., 2005a; Herman et al., 1997; Kobiler et al., 2007). Except when cIII is overexpressed, lysogeny is only established when the activity of these proteases (FtsH, Lon, and perhaps others) is low. Once established, lysogeny is a stable state until lysogens are exposed to ultraviolet light or other DNA-damaging agents that lead to the activation of RecA, which in turn accelerates autocleavage of the λ repressor CI. Loss of CI leads to prophage induction and the lytic cycle. The mechanism by which phage λ decides whether to grow lytically or become a lysogen is reviewed elsewhere (Court et al., 2007; Friedman and Court, 2001; Gottesman and Weisberg, 2004; Ptashne, 2006). However, Table IV contains the host–phage protein–protein interactions critical for gene expression and thus the genetic switch of phage λ.

TABLE IV.

Published phage λ–host interactionsa

| λ | Host | Description | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transcription | |||

| CI | RecA | RecA degrades CIb | Kobiler et al., 2004 |

| CI | RpoA | Kędzierska et al., 2007 | |

| CI | RpoD | Li et al., 1994; Nickels et al., 2002 | |

| CII | ClpYQ | ClpYQ degrades CII in vitro | Kobiler et al., 2004 |

| CII | ClpAP | ClpAP degrades CII in vitro | Kobiler et al., 2004 |

| CII | HflD | HflD makes CII more vulnerable to FtsH (hfl, high-frequency lysogenization) | Kihara et al., 2001 |

| CII | HflBc | HflB (= FtsH) protease degrades cII | Kobiler et al., 2002; Shotland et al., 2000 |

| CII | RpoA | Kędzierska et al., 2004; Marr et al., 2004 | |

| CII | RpoD | Kędzierska et al., 2004 | |

| CIII | HflB | CIII inhibits HflB; HflB degrades CIII | Herman et al., 1997; Kornitzer et al., 1991 |

| gpN | NusA | Transcriptional regulation | Friedman and Court, 2001 |

| gpN | Lon | Lon degrades gpN | Kobiler et al., 2004; Gottesman et al., 1981 |

| gpQ | σ70 | gpQ makes RNAP insensitive to cis terminal | Marr et al., 2001;Nickels et al., 2002; Roberts and Roberts, 1996; Roberts et al., 1998 |

| Head | |||

| gpB | GroE | genetic interaction; E. coli GroE | Ang et al., 2000; Georgopoulos et al., 1973; Murialdo, 1979 |

| gpE | GroE | genetic interaction | Georgopoulos et al., 1973 |

| Tail | |||

| gpJ | LamB | LamB is the E. coli receptor | Buchwald and Siminovitch, 1969; Clement et al., 1983; Mount et al., 1968; Wang et al., 2000a; Werts et al., 1994 |

| Stf | OmpC | OmpC is a secondary E. coli receptor | Hendrix and Duda, 1992 |

| Recombination | |||

| Xis | Lon | Xis is degraded by E. coli Lon protease | Leffers and Gottesman, 1998 |

| Xis | FtsH | Xis is degraded by E. coli FtsH protease | Leffers and Gottesman, 1998 |

| Xis | Fis | both required for excision | Ball and Johnson, 1991; Cho et al., 2002; Esposito and Gerard, 2003 |

| Int | IHF | Both catalyze recombination at attP/attB | Campbell et al., 2002; Crisona et al., 1999 |

| Gam | RecB | Gam inhibits RecBCD | Marsic et al., 1993 |

| NinB | SSB | NinB also binds ssDNA | Maxwell et al., 2005 |

| Replication | |||

| gpO | ClpXP | ClpXP degrades gpO | Kobiler et al., 2004 |

| gpP | DnaA | Datta et al., 2005b,c | |

| gpP | DnaB | Mallory et al., 1990 | |

CbpA (Wegrzyn et al., 1996) perhaps interacts with DnaA and SeqA (Potrykus et al., 2002; Wegrzyn and Wegrzyn, 2001, 2002).

After DNA damage, RecA bound to single-stranded DNA stimulates autocleavage of the CI repressor (Kobiler et al., 2004).

HflB = FtsH.

5. Anti-termination

Escherichia coli RNA polymerase transcribes λ DNA starting from the immediate early promoters PL and PR, which leads to expression of the N and cro genes, among others. As soon as the gpN-binding sites (nut sites) are transcribed, gpN modifies the transcription complex by recognizing a stem-loop structure in the mRNA and by binding to host Nus proteins [note that gpN interacts with nut RNA (not DNA)]. This modified complex is capable of overriding the termination signal that normally stops immediate early transcription. Because gpN is continually being degraded by the Lon protease, ongoing anti-termination requires continual transcription of the N gene (Fig. 6). In addition to the anti-terminator for early lytic genes (gpN), a second anti-terminator, gpQ, is required for late gene expression. GpQ anti-termination differs from that of gpN in that gpQ binds to the “Q binding element” (QBE, also known as the qut site) of the PR′ promotor (i.e., unlike the gpN protein, gpQ binds DNA). When RNA polymerase (RNAP) initiates transcription at the PR′ promotor, it almost immediately pauses at a pause-inducing sequence. Pausing allows gpQ to contact σ70 in the RNAP, which causes a conformational change in the enzyme that enables gpQ to bind the β subunit (RpoB). The gpQ-containing RNAP is then able to override the termination signal at tR′ (Deighan et al., 2008; Nickels et al., 2002).

FIGURE 6.

Interactions of phage λ with its host, E. coli. (A) Overview of λ activities in E. coli: (a) free phage, (b) binding and entry, (c) DNA circularization and supercoiling, (d) transcription, (e), replication, and (f) virion assembly. Details are shown in B–E. (B) Infection and DNA ejection, (C) DNA ligation, (D) gene regulation. An asterisk means weakly bound to the RNA polymerase. (E) DNA replication. Phage proteins are labeled in red, host proteins in black. Modified after Das (1992) and Mason and Greenblatt (1991).

6. Replication

After λ gene O and P protein synthesis, replication of the phage genome is initiated (Fig. 6). Replication initiation starts with dimeric gpO bound to the four 18-bp direct repeats of the λ origin, located within the sequence of the O gene. Each repeat binds a gpO dimer, leading to a total of eight monomers bound directly to the DNA, in addition to non-DNA-bound gpO that associates with the complex solely by PPIs (Dodson et al., 1986). This large nucleoprotein complex is called the O-some. GpP extracts the host DnaB helicase from its native complex with DnaC (Zylicz et al., 1989). The DnaB helicase is inactive as long as it is tightly associated with gpP. The gpP–DnaB pair is then added to the O-some through interactions between gpP and gpO. Three host heat shock chaperone proteins—DnaK, DnaJ, and GrpE—are subsequently recruited (DnaK through direct interaction with gpP and gpO) and activate the DnaB helicase by liberating it from its inhibitory interaction with gpP. Finally gpP and the chaperones are released, and replication starts with the help of the host DnaG primase, DNA polymerase III, gyrase, and single-stranded DNA-binding (SSB) proteins (Dodson et al., 1986; LeBowitz and McMacken, 1986). The RNA polymerase β subunit was shown to interact directly with gpO (Szambowska et al., 2010). Even though not yet fully understood, how E. coli RNA polymerase activates λ ori seems to be far more complex than the original idea that it simply changed DNA topology.

Studies on λ ori-dependent plasmids have revealed interactions with even more host proteins, including the DnaJ homolog CbpA (Wegrzyn et al., 1996), and through transcriptional activation of origin activity, perhaps also with DnaA and SeqA (Potrykus et al., 2002; Wegrzyn and Wegrzyn, 2001, 2002). As λ ori-dependent plasmid maintenance and copy number are very sensitive to changes in host physiology, interactions of the O-some with additional proteins may yet be revealed.

7. The λ interactome

A λ Y2H interactome analysis has been completed (Rajagopala et al., 2011). All λ open reading frames (ORFs) were cloned and tested in all possible pairs for interactions, using three different Y2H vectors. These screens identified 97 interactions among 68 tested λ proteins, of which 16 were known previously. Notably, because only 33 interactions had been reported previously, this screen found more than 50% of all previously published interactions in a single experiment! At least 18 of the newly observed Y2H interactions seem to be plausible, based on the functions of the interacting proteins, indicating that even in λ many new discoveries can be made. Interestingly, relatively few interactions involving morphogenetic proteins were revealed, and possible reasons for the still significant fraction of apparent false negatives are discussed later.

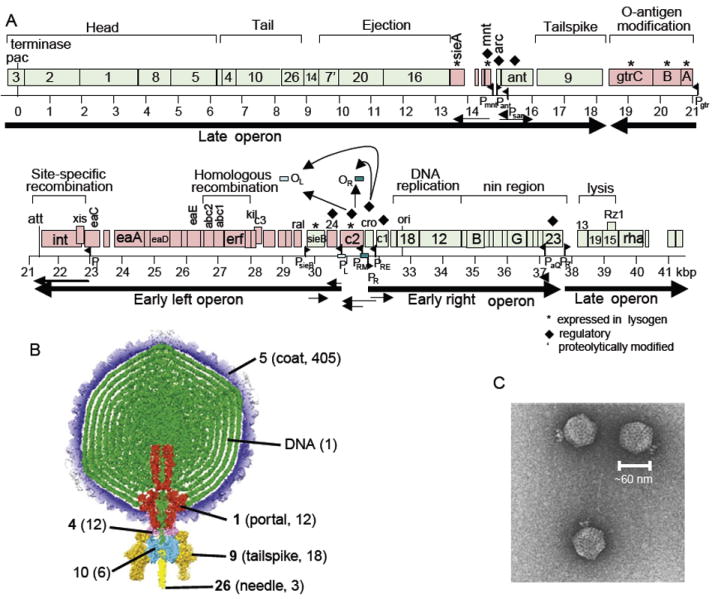

C. Salmonella phage P22

P22 infects Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium and was originally isolated by Zinder and Lederberg (1952). It is a temperate member of Podoviridae. Its virion proteins are not particularly closely related to other tailed phage groups, but its early genes and overall lifestyle are very closely related to phage λ. For this reason, it is often placed in the “lambdoid” phage group. Phage P22 is also a very important tool for those who use Salmonella genetics, as it is particularly easy to handle in the laboratory and is a very good generalized transducing phage (i.e., it packages a significant amount of host DNA by accident and can be used to move host alleles from one Salmonella strain to another).

1. P22 life cycle

The early operons of P22 are organizationally similar to those of λ and carry parallel prophage repressor, Cro, recombination, DNA replication, and transcription anti-termination functions (Susskind and Botstein, 1978). The P22 repressor has a different DNA operator target specificity from that of λ repressor and encodes nonhomologous types of recombination and replication proteins, but its late operon anti-termination protein is 97% identical to that of λ and has the same target specificity. Unlike λ, in addition to its prophage repressor (C2) and lysogeny control proteins (C1, C3, Cro), P22 carries an “immunity I” region that encodes an anti-repressor protein, Ant, that binds to the prophage repressor and blocks its ability to bind its operator. Two additional repressors, Mnt and Arc, regulate Ant synthesis (Susskind and Botstein, 1975; Vershon et al., 1987a,b). Also, instead of a protein that recruits the host DnaB protein to the replication origin, P22 encodes its own DnaB homologue (Backhaus and Petri, 1984; Wickner, 1984). The repressed P22 prophage encodes several “lysogenic conversion” genes, several of which encode a set of three Gtr (glucose transfer) proteins that modify the host O-antigen polysaccharide by glucosylation (Broadbent et al., 2010; Makela, 1973; Vander Byl and Kropinski, 2000). Finally, P22 has been studied as a prototypical headful DNA packaging phage, which is different from the packaging strategies used by the other phages discussed here; unlike these other phages that package DNA between two specific nucleotide sequences in the DNA substrate, P22 packages DNA until the head is full and the nucleotide sequence at the termination point does not matter (Casjens and Hayden, 1988; Jackson et al., 1978; Tye et al., 1974).

2. P22 virion assembly

The P22 virion is assembled by proteins encoded by 14 genes in its late operon (Fig. 7) (Botstein et al., 1973; Eppler et al., 1991; King et al., 1973; Poteete and King, 1977; Youderian and Susskind, 1980). Some P22-like phages, for example, phages ε34 and L, have a 15th virion assembly gene, dec, at the promoter proximal end of the cluster, whose encoded protein “decorates” the outside of the head and stabilizes it (Gilcrease et al., 2005; Tang et al., 2006; Villafane et al., 2008). The P22 late operon encodes lysis proteins very similar to those of λ; however, the virion assembly genes are not closely related to λ or to any other tailed phage type. P22 virion assembly is best known for the fact that its head-assembling scaffolding protein was the first to be discovered and studied (Cortines et al., 2011; King and Casjens, 1974; Prevelige et al., 1988; Weigele et al., 2005). The P22 procapsid assembles as a complex of 415 coat protein molecules, 12 portal ring subunits, and about 250 scaffolding protein molecules. At about the time when DNA is packaged, all 250 scaffolding proteins are released intact from the procapsid and are reused with newly synthesized coat protein in subsequent rounds of procapsid assembly. Thus, the P22 scaffolding protein acts catalytically in head assembly and individual molecules can participate in at least five rounds of procapsid assembly. A particularly high-resolution asymmetric cryo-EM reconstruction of the virion has been determined (Lander et al., 2006; Tang et al., 2011), and because assembly of the four proteins of its short tail has also been quite well studied [X-ray structures are known for three tail proteins and the portal protein (Olia et al., 2006, 2007; Steinbacher et al., 1997)], the P22 virion is perhaps the best understood of all tailed phage virions. The details of P22 virion assembly have been reviewed in light of its evolution and genome mosaicism (Casjens and Thuman-Commike, 2011), and the authors refer the reader to this review for further details. The published PPIs of phage P22 are summarized in Table V. Interactions between P22 and its host are much less well studied than those of λ and are mostly understood by homology arguments in the case of proteins that are similar in the two phages. Known P22–host interactions are listed in Table VI.

FIGURE 7.

Genome and virion of phage P22. (A) Genome of phage P22 with a scale in kbp below. Green open reading frames (ORFs; rectangles) are transcribed left to right; red ORFs are transcribed right to left. Known RNA polymerase promoters and transcripts are shown as black flags and arrows, respectively. (B) The asymmetric (not icosahedrally averaged) P22 virion three-dimensional cryo-EM reconstruction from Tang et al. (2011). Numbers in parentheses indicate molecules/virion, and bold numbers indicate proteins for which X-ray structures are known. (C). Negatively stained electron micrograph of P22 virions.

TABLE V.

P22 intraphage protein interactions

| P22 1 | P22 2 | Description | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| gp3 | gp3 | Small terminase subunit; homononomer in solution | Nemecek et al., 2007, 2008 |

| gp3 | gp2 | Purify as complex; bind each other in vitro | Nemecek et al., 2007; Poteete and Botstein, 1979 |

| gp2 | gp1 | gp2 is large terminase subunit; assembles in packaging motor to gp1 by analogy with other phages (gp2 by itself is monomer in solution); evolutionary argument for P22 gp2–gp1 interaction | Casjens, 2011 |

| gp1 | gp1 | Portal protein; homododecamer; EM of 12-mer; EM of virion; X-ray structure | Bazinet et al., 1988; Lander et al., 2006; Olia et al., 2011 |

| gp1 | gp5 | Purify as complex (procapsids); three-dimensional (3D) reconstructions of virion and procapsid | Botstein et al., 1973; Chen et al., 2011; Lander et al., 2006 |

| gp1 | gp8 | gp8 required for assembly of gp1 into procapsid; interaction seen in procapsid 3D reconstruction | Chen et al., 1989; Greene and King, 1996; Weigele et al., 2005 |

| gp8 | gp8 | Scaffolding protein; forms homodimers and tetramers in solution | Parker et al., 1997 |

| gp8 | gp5 | Purify as complex (procapsid); bind in vitro | Fuller and King, 1982; Greene and King, 1994; Parker et al., 1998 |

| gp5 | gp5 | Coat (major capsid) protein; forms T=7 l icosahedral shell of virion | Botstein et al., 1973; Casjens, 1979; Lander et al., 2006 |

| gp5 | gp1 | Purify as complex (procapsids); interaction seen in 3D reconstruction | Chen et al., 2011; Lander et al., 2006 |

| gp4 | gp4 | Tail protein; monomer in solution (naturally unfolded?); gp4s barely touching each other in dodecamer ring in virion (i.e., contacts not large); EM, X-ray structure | Olia et al., 2011; Tang et al., 2011 |

| gp4 | gp5 | Contact in high-resolution 3D reconstruction of virion | Olia et al., 2006, 2011; Tang et al., 2011 |

| gp4 | gp1 | Order of assembly, EM, 3D reconstruction; X-ray cocrystal structure | Olia et al., 2006, 2011; Tang et al., 2011 |

| gp4 | gp10 | 12 gp4s contact 6 gp10s; order of assembly, EM, 3D reconstruction | Lander et al., 2006; Olia et al., 2007 |

| gp4 | gp9 | gp4 ring contacts 6 gp9 trimers; 3D reconstruction | Lander et al., 2006 |

| gp10 | gp10 | Tail protein; probably hexamer in solution; 3D reconstruction | Lander et al., 2006; Olia et al., 2007 |

| gp10 | gp9 | 6 gp4s contact 6 gp9 trimers; 3D reconstruction | Lander et al., 2006 |

| gp10 | gp26 | 6 gp10s contact one gp26 trimer | Landeret al., 2006 |

| gp26 | gp26 | Tail needle protein; trimer in solution - crystal structure; one trimer in virion | Olia et al., 2007 |

| gp16 | gp8 | Mutants of gp8 do not incorporate gp16 into virion | Chen et al., 1989; Greene and King, 1996; Weigele et al., 2005 |

| C1 | C1 | C1 is homologue of λ CII; homotetramer | Ho et al., 1992 |

| Mnt | Mnt | Repressor of antirepressor gene; tetramer | Nooren et al., 1999 |

| Arc | Arc | Repressor of antirepressor gene; dimer in solution, tetramer on DNA | Bowie and Sauer, 1989; Breg et al., 1990; Brown, Bowie and Sauer, 1990 |

| Ant | C2 | Antirepressor; binds to and inhibits C2 repressor | Susskind and Botstein, 1975 |

| gp9 | gp9 | Tailspike protein; trimer in solution, 6 trimers in virion; crystal structure; binds to polysaccharide on cell surface | Lander et al., 2006; Steinbacher et al., 1994, 1997 |

| Int | Xis | Form heteromultimer | Cho et al., 2002 |

| Xis | Xis | Excisionase; homomultimers | Mattis et al., 2008 |

| Erf | Erf | Recombination protein; homomultimeric ring of 10–14 subunits | Poteete et al., 1983 |

| C3 | C3 | C3 is homologue of λ CIII; λ CIII is dimer by disulfide bond; P22 interaction by homology with λ CIII | Halder et al., 2007 |

| SieB | Esc | Similar to λ but not studied in detail | Ranade and Poteete, 1993a |

| C2 | C2 | Prophage repressor homologue of λ CI; homodimer | De Anda et al., 1983 |

| Cro | Cro | Dimer; solution studies and crystal structure | Darling et al., 2000; Newlove et al., 2004 |

| gp18 | gp12 | Origin binding protein gp18 recruits DnaB-like gp12 to replication origin by analogy with λ (note that gp12 is not a homologue of λ P protein; gp18 is homologous to λ O protein only in N-terminal domain) | Backhaus and Petri, 1984 |

| Rz | Rz1 | Rz and Rz1 are supposed to bind to one another and form a bridge that spans the periplasm in phage λ; P22 gp15 and Rz1 should do the same by homology. | Summer et al., 2007 |

| gp13 | gp13 | Holin forms rings of large diameter in λ; by homology same should be true of P22 holin | Savva et al., 2008 |

| gp13 | gp13′ | Antiholin–holin interactions delay the formation of holin rings in λ; by homology same should be true in P22 | Rennell and Poteete, 1985 |

| Dec | Dec | Trimer; Note that P22 has no Dec, but its very close relative phage L does and L Dec binds to P22 capsids. | Tang et al., 2006 |

| Dec | gp5 | Dec occupies a subset of the quasi-equivalent local threefold positions on the shell | Tang et al., 2006 |

TABLE VI.

P22–host protein interactions

| P22 | Host | Description | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| gp5 | GroEL | Solution studies | de Beus et al., 2000 |

| gp24 | NusA? etc? | Homologue/analogue of λ gpN; likely binds same host factors as λ gpN | Franklin, 1985; Hendrix and Casjens, 2006 |

| C3 | FtsH(HflB) | C3 is homologue of λ CIII; inhibition of FstH by homology with λ CIII | Semerjian et al., 1989 |

| C1 | FtsH(HflB) | C1 is homologue of λ CII; CII is degraded by FtsH | Backhaus and Petri, 1984 |

| C2 | RecA | P22 repressor autocleavage stimulated by RecA binding like λ | Prell and Harvey, 1983; Tokuno and Gough, 1976 |

| Xis, gp18, gp24, C1 | Host protein degradation machinery | These may be degraded analogously to their λ homologues, but direct information is not available | Backhaus and Petri, 1984 |

| gp23 | RNA polymerase? | By homology to λ; gp23 is nearly identical to λ gpQ | Pedulla et al., 2003 |

| gp12 | Host replication machinery | Possible interaction with host DnaG primase | Wickner, 1984 |

| Abc2 | RecC | Solution studies | Murphy, 2000 |

3. Comparison of P22 and λ interactomes

As noted earlier, comparison of P22 and λ is a particularly informative way to understand the kinds of relationships among the proteins of different tailed phages. The “lambdoid” phages all encode similar functions and have similar gene organization, but these “similar functions” can be of several different types. Because these phages undergo a significant amount of horizontal transfer of genetic information (especially if they are “closely” related), their functions can be homologous or even nearly identical (Casjens, 2005; Hendrix, 2002). For example, the two “gpQ” late operon control anti-termination proteins of the two phages are nearly identical and can replace one another in function. A second kind of relationship is represented by the prophage repressors. These proteins from the two phages have weak but recognizable homology and similar folds, and probably interact with host proteins the same way, but have different operator-binding specificity. Thus, one repressor cannot functionally replace the other without additional changes in the DNA-binding sites of the protein. A third kind of relationship is that of the virion coat, terminase, and portal proteins, λ gpE, gpA, and gpB and P22 gp5, gp2, and gp1, respectively. These proteins have the same functions in the two phages—coat protein and DNA packaging nuclease/motor ATPase and procapsid DNA entry channel, respectively (summarized in Hendrix and Casjens, 2006). These cognate proteins are not recognizably similar in overall amino acid sequence between the two phages, although the two ATPase proteins have similar ATP-binding motifs. However, the two proteins almost certainly have the same basic fold. Thus, gpE and gp5 and gpA and gp2, as well as gpB and gp1, are all very likely ancient homologous pairs that have diverged beyond the point of having recognizable sequence similarity. Finally, similar functions are performed by nonhomologues in the two phages. Examples of this relationship are the (i) nonhomologous Exo (λ) and Erf (P22) proteins that catalyze homologous recombination in completely different ways (Little, 1967; Poteete and Fenton, 1983); (ii) the endolysin proteins gpR and gp19, where the λ protein is a transglycosylase and the P22 protein is a true lysozyme that both cleave the same peptidoglycan bond (Bienkowska-Szewczyk et al., 1981; Rennell and Poteete, 1989); (iii) the gpW and gp4 proteins, which bind between the portal ring of the head and the tail and yet have no recognizable homology or structural similarity; and (iv) the λ receptor binding “fiber” (gpJ and STF) and P22 tailspike (gp9), which have no homology, recognize different structures, and act in different ways [the P22 gp9 enzyme cleaves its polysaccharide receptor (Iwashita and Kanegasaki, 1976)]. Thus, there are potentially a number of different ways in which parallel λ and P22 functions might interact with the hosts of these two phages, and it will be interesting to understand these in detail in both cases. But are there very similar phage proteins that have different host interactions? Do very different phage proteins that have the same function have equally different host interactions? Although no such situations have been identified to date, it remains possible. A comparison of PPIs in λ and P22 is given in Tables VII and VIII.

TABLE VII.

Comparison of λ and P22 interactions

| λ 1 | λ 2 | P22 1 | P22 2 | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| gpA | gpB | gp2 | gp1 | Likely similar contacts—by evolutionary argumenta |

| gpA | gpNu1 | gp2 | gp3 | Likely similar contacts—by evolutionary argument a |

| gpNu1 | gpNu1 | gp3 | gp3 | gpNu1 N-terminal fragment is dimer; gp3 is nonomer; not known if they have the same fold (i.e., are ancient homologues) |

| gpW | gpB | gp4 | gp1 | gpW and gp4 have no known homology, but are analogous in that they are the first proteins to bind the underside of the the portal ring; gp4 has no structural homology to λ gpFII or gpW (Cardarelli et al., 2010; Olia et al., 2011) |

| gpW | gpFII | No clear gpFII homologue in P22 (gp4 and gp10 of P22 have no sequence similarity) | ||

| gpB | gpB | gp1 | gp1 | Both form dodeamer portal ringsa |

| gpC | gpE | No gpC analogue in P22 | ||

| gpC′ | gpB | No gpC analogue in P22 | ||

| gpC | gpNu3 | No gpC analogue in P22 | ||

| gpNu3 | gpNu3 | gp8 | gp8 | Monomer/dimer/tetramer for gp8; monomer/dimer for gpNu3 |

| gpB | gpE | gp1 | gp5 | Seen in reconstructionsa |

| gpNu3 | gpB | gp8 | gp1 | Scaffolds required for portal assembly into procapsid |

| gp8 | gp5 | Scaffold–coat interaction not studied for λ | ||

| gpD | gpD | Dec | Dec | Both trimers; bind slightly different sites.a Note that P22 has no Dec, but its very close relative phage L does and L Dec binds to P22 capsids |

| gpE | gpE | gp5 | gp5 | Both make icosahedral T=7 head shellsa |

| gpU | gpU | No analogue in P22 | ||

| gpD | gpE | Dec | gp5 | Dec is more discriminatory than D, i.e., unlike D, Dec does not occupy all of the quasi-equivalent local threefold positions on the shell |

| gp4 | gp5 | Unkown in λ | ||

| gp4 | gp10 | No gp10 analogue in λ (but see gpFII above) | ||

| gp4 | gp9 | No gp9 analogue in λ (but see Stf below?) | ||

| gp10 | gp9 | No gp9 analogue in λ (but see Stf below?) | ||

| gp10 | gp10 | No gp10 analogue in λ (but see gpFII above) | ||

| gp10 | gp26 | No gp10 or gp26 (?) analogue in λ | ||

| gp26 | gp26 | No gp26 analogue in λ (maybe gpJ?) | ||

| Stf | Stf | gp9 | gp9 | Both trimers (Stf by homology to T4 fibers); analogues, not homologues |

| gpU | gpV | No analogues in P22 | ||

| gpV | gpV | No analogue in P22 | ||

| gpO | gpP | gp18 | gp12 | gpO and gp18 are homologous but gpP and gp12 are not; nonetheless, a good argument can be made that gp18 and gp12 must interact similarly to gpO and gpP to get replication started |

| gpW | gpW | gp4 | gp4 | Analogues—first proteins to bind below the portal ring (see gpW–gpB interaction above) |

| gpFI | gpA | No gpFI analogue in P22 | ||

| gpFI | gpE | No gpFI analogue in P22 | ||

| gpH | gpG/gpGT | No analogues in P22 | ||

| gpV | gpGT | No analogues in P22 | ||

| gpH | gpV | No analogues in P22 | ||

| Arc | Arc | No analogue in λ | ||

| Ant | C2 | No Ant in λ | ||

| Mnt | Mnt | No analogue in λ | ||

| CI | CI | C2 | C2 | Homologues (Sevilla-Sierra et al., 1994) |

| Exo | Bet | Erf | Erf | λ Exo and P22 Erf proteins are not homologues and function in basically different ways, but they are both essential for homologous recombination |

| SieB | Esc | SieB | Esc | Good homologues in P22 but they are unstudied |

| CII | CII | C1 | C1 | Homotetramers in both cases |

| Xis | Int | Xis | Int | Xis proteins are quite different |

| Xis? | Xis? | Xis | Xis | Monomer in λ, but binds cooperatively so could interact on DNA (Abbani et al., 2007); multimer in P22 |

| CIII | CIII | C3 | C3 | C3 is homologue of λ CIII; λ CIII is dimer (Halder et al., 2007); P22 interaction by homology with λ CIII |

| Cro | Cro | Cro | Cro | Both homodimers |

| gpRz | gpRz1 | gp15 | gp15 | Predicted for P22 by homology |

Not recognizably similar in amino acid sequence but very likely ancient homologues.

TABLE VIII.

Comparison of phage λ–host and P22–host interactions

| λ | Host | P22 | Host | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CII | HflB | C1 | HflB | Should be true for P22 by homology |

| CIII | HflB | C3 | HflB | Should be true for P22 by homology |

| gpJ | LamB | P22 tails recognize polysaccharide so no analogue in P22 | ||

| Stf | OmpC | P22 tails recognize polysaccharide so no analogue in P22 | ||

| Xis | Lon | Xis | Lon? | Might be true for P22 by homology |

| Xis | FtsH | Xis | FtsH? | Might be true for P22 by homology |

| gpN | RNAP | gp24 | RNAP? | Likely true for P22 by similarity of function |

| Int | IHF | P22 does not interact with IHF (Cho et al., 1999) | ||

| Xis | Fis | Unknown for P22 | ||

| gpQ | σ70 | gp23 | σ70 | Likely true for P22 by similarity of function |

| P | DnaB | No analogue of P in P22 | ||

| gp12 | DnaG? | No analogue of 12 in λ | ||

| gpE | GroE | gp5 | GroE | |

| gpB | GroE | Not known for P22 | ||

| gpN | Lon | gp24 | Lon | Not known for P22 |

| CI | RecA | C2 | RecA | Might be true for P22 by homology and induction by ultraviolet light |

| CII | ClpYQ | C1 | ClpYQ | Might be true for P22 by homology |

| CII | ClpAP | C1 | ClpAP | Might be true for P22 by homology |

| gpO | ClpXP | gp18 | ClpXP | Might be true for P22 by homology |

| gpN | NusA | gp24 | NusA | Likely true by similarity of function |

| CII | HflD | C1 | HflD | Might be true for P22 by homology |

| Gam | RecB | No Gam in P22 | ||

| Abc2 | RecC | No Abc2 in λ |

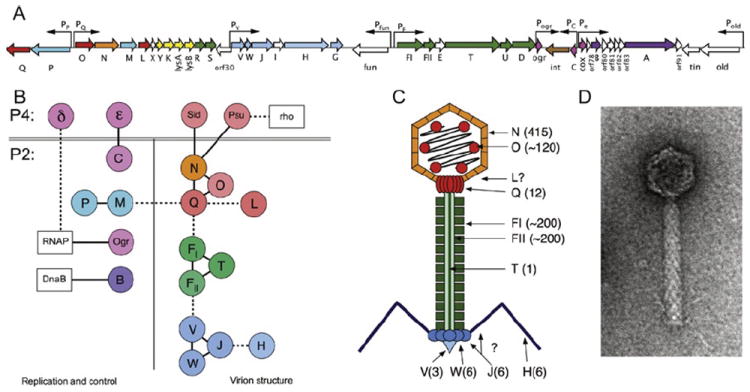

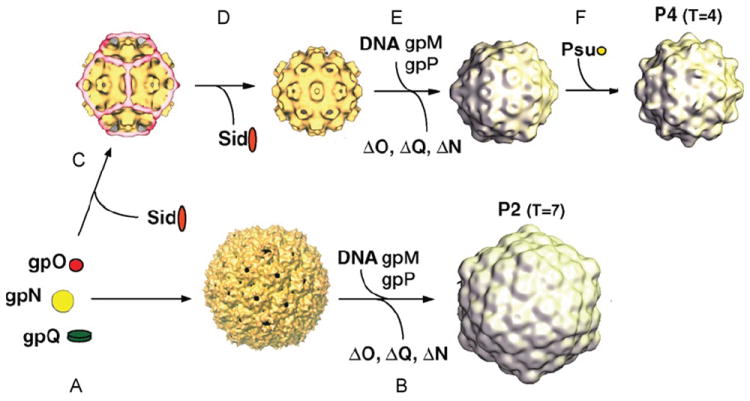

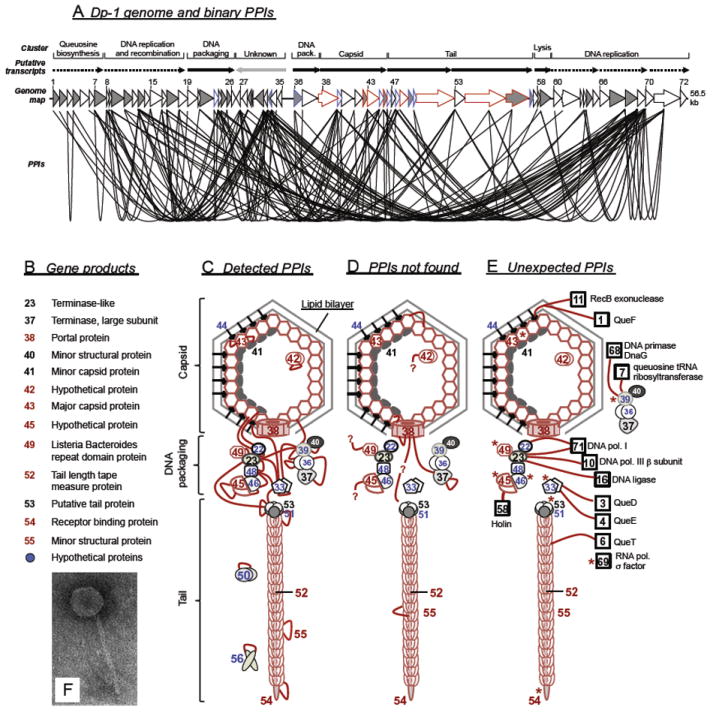

D. Enterobacteriophage P2 and its satellite phage, P4

Bacteriophage P2 was originally isolated from the Lisbonne & Carrère strain of E. coli by Bertani in 1951 and is a member of the Myoviridae family of viruses. It has an icosahedral head and a contractile tail and is a 33.6-kb double-stranded DNA genome (Bertani, 1951; Bertani and Six, 1988; Nilsson and Haggård-Ljungquist, 2006). P2-like prophages are common in the environment (Breitbart et al., 2002) and are present in about 30% of strains in the E. coli reference collection (Nilsson et al., 2004).

Bacteriophage P2 has attracted much interest as a “helper” for bacteriophage P4, an 11.6-kb replicon that can exist either as a plasmid or integrated into the host genome as a prophage (Briani et al., 2001; Deho and Ghisotti, 2006; Lindqvist et al., 1993). P4 lacks genes encoding major structural proteins, but can utilize the structural gene products encoded by P2 for assembly of its own capsid (Christie and Calendar, 1990; Lindqvist et al., 1993; Six, 1975). An overview of the P2 structural biology and a summary of its interactions are shown in Figure 8 and Table IX.

FIGURE 8.

(A) Schematic diagram of the 33.6-kb P2 genome. Open reading frames (ORFs) are indicated by arrows that reflect their direction and size and are color coded as follow: red/orange, capsid-associated proteins (gpQ, O, N, L); blue, terminase proteins (gpP, M); yellow, lysis proteins (gpY, K, lysA, lysB); green, tail-related proteins (gpR, S, FI, FII, T, U, D); blue, base plate and tail fiber-related proteins (gpV, W, J, H, G); pink, transcriptional control proteins (Ogr, C, Cox); brown, integrase (Int); and purple, replication-related proteins (gpA,B). Nonessential genes and ORFs of unknown function are white. Promoters are indicated by arrows above ORFs. (B) Diagram of protein–protein interactions listed in Table IX. Each P2 and P4 protein is shown as a circle, colored as given earlier. Host proteins are shown as white boxes. (C) Schematic diagram of the P2 virion, color coded as given earlier. Copy numbers of proteins, when known, are indicated in parentheses. (D) Electron micrograph of a P2 virion, stained negatively with uranyl acetate.

TABLE IX.

Protein–protein interaction of phages P2 and P4

| Protein | Function | Interactions | Notes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P2–P2 proteins | ||||

| gpC | Immunity repressor | Dimer | Y2H 3D structure | Eriksson et al., 2000; Massad et al., 2010 |

| Cox | Transcriptional repressor, excisionase | Tetramer that can self-associate to octamers | In vitro; cross-linking and gel filtration | Eriksson and Haggard-Ljungquist, 2000 |

| Int | Integrase | Dimer | In vitro; cross-linking Y2H | Frumerie et al., 2005 |

| gpFI | Tail sheath | Polymer, six molecules per sheath striation | Electron microscopy | Lengyel et al., 1974 |

| gpFII | Tail tube | Polymer, six molecules per tube striation | Electron microscopy | Lengyel et al., 1974 |

| gpM | Small terminase subunit | Polymer, 8- to 10-fold ring | Biochemistry | Dokland, unpublished data |

| gpM | Small terminase subunit | gpP | Biochemistry | Bowden and Modrich, 1985 |

| gpN | Major capsid protein | T=7 icosahedron (415 copies) | Cryo-EM and 3D reconstruction | Dokland et al., 1992 |

| gpO | Biochemistry | Chang et al., 2008, 2009 | ||

| gpO | Internal scaffolding protein | Dimer | Biochemistry, chromatography | Chang et al., 2008, 2009 |

| gpN | ||||

| gpP | Large terminase subunit | gpP | Biochemistry | Bowden and Modrich, 1985 |

| gpQ | Connector, portal protein | Dodecameric ring | EM, crystallography | Doan and Dokland, 2007; Rishovd et al., 1994 |

| gpT | Tape measure | gpFII (gpFI ?) | Inside tail tube | |

| gpV | Tailspike | Tetramer | Sedimentation velocity and molecular mass determination | Haggard-Ljungquist et al., 1995; Kageyama et al., 2009 |

| gpV | Tailspike | gpW, base plate component. Belongs to the T4 gene 25-like superfamily | Copurification | Haggard-Ljungquist et al., 1995 |

| P2–other phage proteins | ||||

| Tin | Block superinfection of T-even phages | T4 SSB protein (gp32) | Genetic evidence | Mosig et al., 1997 |

| gpC | Immunity repressor | P4 anti-repressor ε | Genetic evidence. Y2H | Geisselsoder et al., 1981; Liu et al., 1998; Eriksson et al., 2000 |

| gpN | Major capsid protein | P4 Sid; size determinator, external scaffold | Cryo-EM and 3D reconstruction | Marvik et al., 1995; Wang et al., 2000; Dokland et al., 2002 |

| gpN | Major capsid protein | P4 Psu; polarity suppressor; decoration protein | Cryo-EM and 3D reconstruction | Dokland et al., 1993 |

| P2–host proteins | ||||

| gpB | Helicase loader. | E. coli helicase DnaB | Genetic evidence. | Sunshine et al., 1975; Funnell and Inman, 1983; Odegrip et al., 2000 |

| Required for lagging strand synthesis | Electron microscopy. | |||

| In vitro binding. | ||||

| Ogr | Transcriptional activator of late operons | E. coli RNA polymerase α C-terminal domain | Genetic evidence | Sunshine and Sauer, 1975; Fujiki et al., 1976; King et al., 1992; Ayers et al., 1994; Wood et al., 1997 |

| P4–host proteins | ||||

| Psu | Polarity suppressor; anti-terminator | Rho | Genetics; chemical cross-linking | Sauer et al., 1981; Pani et al., 2009 |

| Delta | Transcriptional activator, contains two Ogr domains | E. coli RNA polymerase | Genetics; homology to Ogr | Julien et al., 1997 |

1. Gene control circuits

The decision whether to grow lytically or form a lysogen after P2 infection is dependent on the levels of two repressors: the immunity repressor gpC, which blocks lytic growth, and Cox, which blocks the expression of the genes required for lysogenization. GpC acts as a symmetric dimer, and its three-dimensional structure has been determined (Eriksson et al., 2000; Massad et al., 2010). Cox is multifunctional and acts as a repressor, as well as an excisionase, thereby coupling the transcriptional switch that controls lytic growth versus formation of lysogeny with the integration/excision of the phage genome in or out of the host chromosome. Cox is a tetramer in solution that self-associates to octamers in the absence of DNA (Eriksson and Haggard-Ljungquist, 2000). The transcriptional activator Ogr is required to turn on late gene transcription. Ogr is a Zn finger-containing protein that interacts with the α subunit of the E. coli RNA polymerase, recruiting it to the late promoters (Ayers et al., 1994; Fujiki et al., 1976; King et al., 1992; Sunshine and Sauer, 1975; Wood et al., 1997).

Some P2 prophage genes are not blocked by the action of gpC and instead are expressed from the prophage providing the host cell with new properties. Among these “lysogenic conversion” genes, P2 has three genes, old, fun, and tin, that block superinfection of unrelated phages, but only gpTin is known to have a PPI. P2 gpTin excludes phage T4 by binding to and poisoning T4 gp32 (SSB), thereby inhibiting DNA replication (Mosig et al., 1997).

Satellite phage P4 has to get access to the morphogenetic genes of its helper P2 to grow lytically. This is accomplished by P4-encoded functions during coinfection with P2. The P4 antirepressor Epsilon derepresses the P2 prophage by interacting with gpC, leading to the expression of P2 lytic genes (Eriksson et al., 2000; Geisselsoder et al., 1981; Liu et al., 1998). P4 also has the capacity to trans-activate P2 late genes in the absence of Ogr using the transcriptional activator Delta. Delta contains two Ogr-like domains and recognizes the same DNA sequence as Ogr. Like Ogr, Delta interacts with the α subunit of E. coli RNA polymerase (Christie et al., 2003; Julien et al., 1997; Souza et al., 1977).

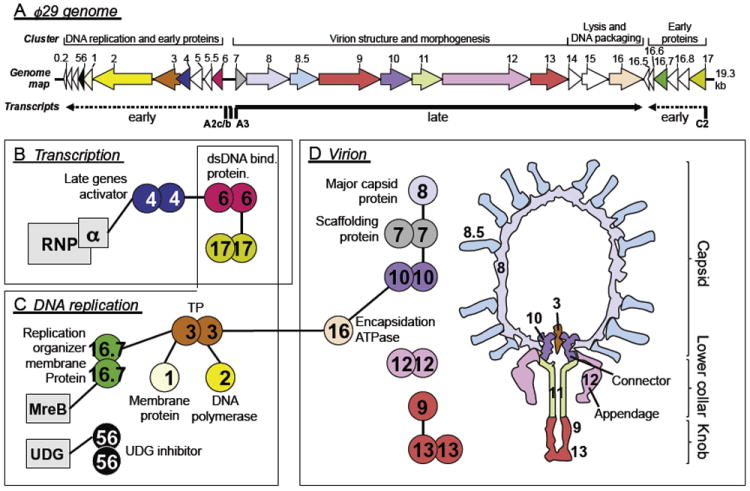

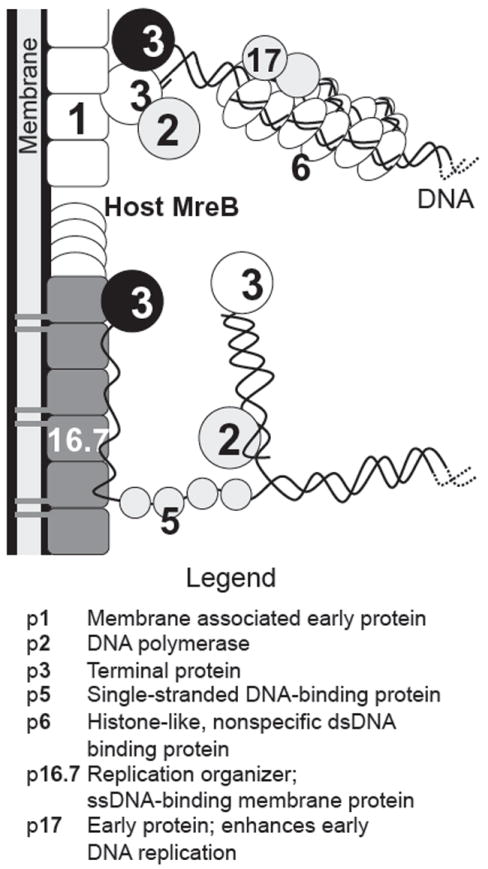

2. P2 DNA replication