Abstract

Histamine releasing factor (HRF), also known as translationally controlled tumor protein (TCTP), is a highly conserved, ubiquitous protein that has both intracellular and extracellular functions. Here, we will highlight the history of the molecule, its clinical implications with a focus on its extracellular functioning, and its potential role as a therapeutic target in asthma and allergy. The cells and cytokines produced when stimulated or primed by HRF/TCTP are detailed as well as the downstream signaling pathway that HRF/TCTP elicits. While it was originally thought that HRF/TCTP interacted with IgE, the finding that cells not binding IgE also respond to HRF/TCTP called this interaction into question. HRF/TCTP, or at least its mouse counterpart, appears to interact with some, but not all IgE and IgG molecules. HRF/TCTP has been shown to activate multiple human cells including basophils, eosinophils, T cells, and B cells. Since many of the cells activated by HRF/TCTP participate in the allergic response, extracellular functions of HRF/TCTP may exacerbate the allergic, inflammatory cascade. Particularly exciting is that small molecule agonists of Src homology 2-containing inositol phosphatase-1 have been shown to modulate the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/AKT pathway and may control inflammatory disorders. This review discusses this possibility in light of HRF/TCTP.

Keywords: human basophils, human eosinophils, inducible transgenic mouse, interleukin 4, interleukin 13, translationally controlled tumor protein (TCTP)

Introduction

Histamine releasing factor (HRF) was originally classified as a tumor protein (translationally controlled tumor protein, TCTP) in both mouse acidic tumors and mouse erythroleukemia. In the 1980s, Yenofsky et al named the protein, but its function remained a mystery.1,2 We identified a histamine-releasing activity that was found in late phase fluids from nasal lavages, bronchoalveolar lavage fluids (BAL), and skin blister fluids that directly induced histamine release from basophils isolated from a subpopulation of allergic donors (HRF-Responders [HRF/TCTP-R]).3 By definition, donors with basophils who did not directly respond to HRF were termed HRF-non-responders (HRF/TCTP-NR). After purification and cloning, HRF was found to be identical to TCTP, which is also known as p23.4 Our recombinant molecule was found to have the same properties and ability to induce histamine release from selected donors as did the originally described HRF/TCTP derived from nasal secretions. The protein is ubiquitously expressed as an intracellular protein, and homologs of HRF/TCTP are found in parasites including Plasmodium falciparum, Wuchereria bancrofti, Brugia malayi, and Schistosoma mansoni. All of these parasites possess mast cell/basophil histamine-releasing activity.5–7 Our group, as well as another group, has identified the interaction between HRF and elongation factor-1δ, also known as eElongation factor 1B-β.8,9 Thus, HRF/TCTP may have an intracellular role in interfering with the elongation step of protein synthesis.

HRF/TCTP cellular interactions

Secreted by an endoplasmic reticulum/Golgi-independent route, HRF/TCTP has no leader sequence, as documented by Amzallag et al.10 This group found that secreted HRF/TCTP comes from an existing intracellular pool and co-distributes with tumor suppressor activated pathway-6, a member of a family that is involved in vesicular trafficking and secretory processes.10–12 Our focus has been on the extracellular functions of HRF/TCTP. HRF was initially described as a complete secretagogue for histamine and interleukin (IL)-4 secretion from basophils of allergic donors.13 These donors were thought to have a certain type of IgE that interacted with HRF/TCTP to induce secretion.4 However, it was subsequently demonstrated that HRF/TCTP primed all basophils for histamine release and IL-4 and IL-13 secretion regardless of the type of IgE.14 Additional studies demonstrated that HRF/TCTP did not appear to interact with IgE. Namely, pharmacologic agents that altered HRF/TCTP-induced histamine release, ie, rotterlin, did not affect anti-IgE-induced histamine release.15 Rat basophilic leukemia cells transfected with the α, β, and γ chains of the human IgE receptor, FcɛRI, did not release histamine to HRF/TCTP despite sensitization with IgE molecules from an HRF/TCTP-R-donor.16 HRF/TCTP was shown to stimulate eosinophils to produce IL-8 and induce an intracellular calcium response.17 This was also observed in the eosinophil cell line, AML-3D10, which does not express the α chain of the FcɛR1 on the surface of the cell.17 Very recently, HRF/TCTP was found to have an inflammatory role in mouse models of asthma and allergy, whereby HRF/TCTP was found to exist as a dimer bound to a subset of IgE and IgG antibodies by interacting with its N-terminus and some internal regions with the Fab region of immunoglobulins.18 These interactions were described with mouse HRF/TCTP, which was shown to interact with mouse mast cells.

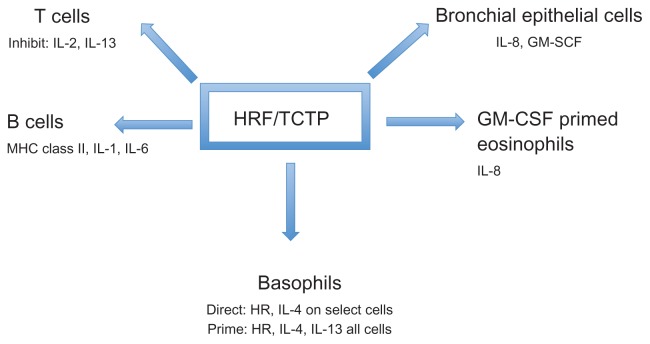

At the level of gene transcription, HRF/TCTP has been shown to inhibit cytokine production from stimulated primary T cells and the Jurkat T cell line.19 Thus, HRF/TCTP, in addition to functioning as a histamine releasing factor, can modulate secretion of cytokines from human basophils, eosinophils, and T cells. It has also been identified as a B cell growth factor by Kang et al. They demonstrated that HRF/TCTP bound to B cells to induce cytokine production.20 More recently, HRF/TCTP was shown to stimulate bronchial epithelial cells to produce IL-8 and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF).21 These effects of HRF/TCTP on different cells are depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Effects of HRF/TCTP on various cell types.

Notes: HRF/TCTP either directly activates (Direct) basophils producing HR and IL-4 on certain cells or primes (Prime) anti-IgE induced HR and IL-4 and IL-13. HRF/TCTP induces IL-8 from GM-CSF-primed eosinophils. Similarly, it produces IL-8 and GM-CSF from bronchial epithelial cells and MHC class II, IL-1 and IL-6 from B cells. Contrary to enhanced interleukin production, HRF/TCTP inhibits IL-2 and IL-13 from T cells.

Abbreviations: GM-CSF, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; HR, histamine release; HRF/TCTP, histamine releasing factor/translationally controlled tumor protein; IL, interleukin; MHC, major histocompatibility complex.

Intracellular functions of HRF/TCTP

While this review focuses mainly on the extracellular functions of HRF/TCTP, it is important to discuss its broad spectrum of intracellular functions. HRF/TCTP is both transcriptionally and post-transcriptionally regulated by calcium.22 It is also a tubulin binding protein and has been shown to transiently associate with microtubules during the cell cycle.23 Additionally, the vitamin D receptor, the NF-κβ regulatory subunit, Iκκγ, the myeloid cell leukemia protein 1, and B-cell lymphoma-extra large (Bcl-XL) have been demonstrated to interact with HRF/TCTP.24–27 High levels of HRF/TCTP have been associated with various cancers, such as prostate, breast, and colon cancer.28–30 Furthermore, the gene for HRF/TCTP was down regulated in tumor reversion and, more specifically, the level was significantly reduced in a lung cancer cell line, A549, revertant cells.31 The role of HRF/TCTP in tumor development may be associated with its anti-apoptotic activity.27,32 This is further supported by reports of HRF/TCTP antagonizing bax function and controlling the stability of the tumor suppressor p53.33,34 In a very recent publication, HRF/TCTP was shown to promote p53 degradation, and p53 directly repressed HRF/TCTP transcription.35 With this report of a previously unrecognized regulatory circuit, HRF/TCTP may be extremely relevant in cancer.35 As previously mentioned, our lab and others have shown involvement of HRF/TCTP in the elongation step of protein synthesis.8,9 Thus HRF/TCTP’s intracellular functions are wide-ranging. Reports describing the extracellular functions, however, have focused on inflammation.

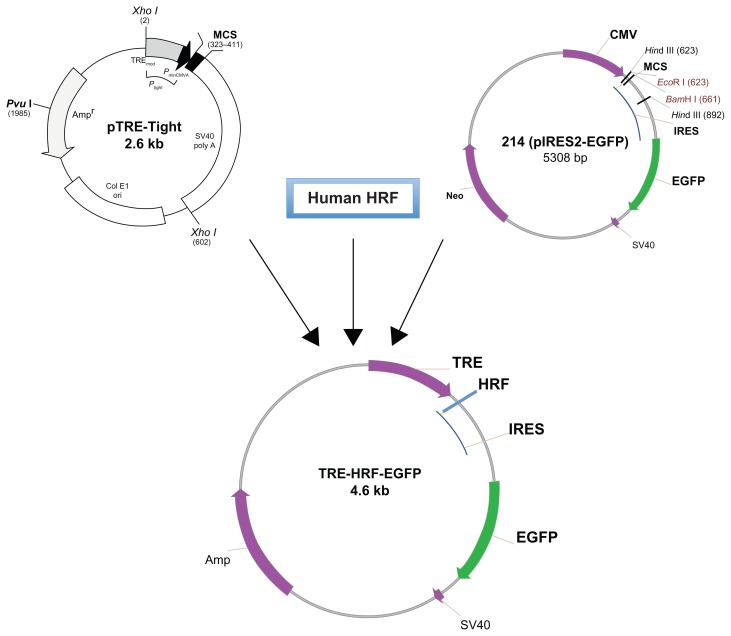

Generation of an inducible HRF/TCTP transgenic mouse

Although HRF/TCTP has been extensively investigated for many years, most studies have been carried out in cultured cells and pathologic samples. Until recently, there has been no established animal model available to explore the function of HRF/TCTP. Several groups generated HRF/TCTP knockout mice by targeted gene disruption, but these HRF/TCTP knockout mice were embryonically lethal.33,36 Since HRF/TCTP is ubiquitous and highly conserved, our approach was to create an inducible HRF/TCTP mouse model using the Tet-On system. We wanted to target HRF/TCTP to the lungs, so we used the CC10 promoter that is expressed in Clara cells of the lung epithelium to generate a transgenic tetracycline response element (TRE)-HRF-enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) mouse. The HRF transgenic plasmid was generated by combining three main components (Figure 2). The first component was the pTRE-tight vector (provided by Dr Zhu in our division), which contains a modified TRE controlling the inducible expression of the gene of interest. The second component was human HRF cDNA, which was cloned from U937 cells using reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR and further confirmed by sequencing (data not shown). The third component was the pIRES2-EGFP vector, provided by Dr Vonakis in our division. The internal ribosome entry site 2 (IRES2) allows the EGFP gene to be expressed individually as a reporter protein along with HRF in order to facilitate the recognition of expression of transgenic human HRF. Thus, the transgenic TRE-HRF-EGFP construct could express HRF and EGFP individually under the regulation of tetracycline or doxycycline. Using this model, we saw an enhanced asthmatic, allergic phenotype after ovalbumin (OVA) challenge. 37 This enhancement is in the C57BL/6 mouse, not the traditional “allergic” BALB/c mouse. The development of an inducible-transgenic HRF/TCTP animal model can be used to yield insights into its underlying pathophysiologic characteristics and provide a tool to define the mechanism of this enhanced or primed phenotype.

Figure 2.

Schema of the transgenic TRE-HRF/TCTP-EGFP plasmid construction.

Note: The human HRF gene was inserted between the TRE and IRES-EGFP elements.

Abbreviations: EGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein; HRF/TCTP, histamine releasing factor/translationally controlled tumor protein; IRES, internal ribosome entry site 2; TRE, tetracycline response element.

The mechanism of HRF/TCTP’s enhanced response yielding increases in IL-4, IgE, and eosinophils after OVA challenge in our transgenic model is currently unknown. That all of these events could be attributed to the action of HRF/TCTP on the basophil is plausible considering the data on HRF/TCTP and the human basophil. We have shown that HRF/TCTP activates human basophils to produce IL-4.13 It is well-known that IL-4 is important for B cell class switching and production of IgE. Furthermore, human basophils possess the β-1 integrin that is important for firm adhesion. The ligand for β-1 integrin, vascular cell adhesion molecule, is upregulated by IL-4 and is important for the transendothelial migration of eosinophils and Th2 cells.38 Therefore, the production of IL-4 by basophils could explain the enhanced asthmatic, allergic phenotype observed after overproduction of HRF/TCTP in our OVA challenged model. This, of course, assumes that the mouse basophil acts in a similar manner as its human counterpart. While the existence of the mouse basophil dates back more than two decades, this cell has reemerged in the last several years as an important initiator of mouse Th2 inflammation.39–41

Because asthma is a multifactorial disease, it is highly unlikely that a single cell such as the mouse basophil is responsible for HRF/TCTP’s effect on asthmatic lung disease. Furthermore, eosinophils and T cells must be considered. It is well-known that the activation, recruitment, and proliferation of the T cell is associated with asthmatic lung disease.42 Given HRF/TCTP’s activation of eosinophils and the increased eosinophils, we find in the BAL fluid of the OVA challenged transgenic mouse, it is logical to examine the role of this cell in the mechanisms of action of HRF/TCTP in vivo.17,37 In the congenitally eosinophil-deficient PHIL mouse, a diminution of Th2 responses occurs.43 Furthermore, eosinophils also secrete IL-4 and act as antigen-presenting cells, yielding T cell activation after allergen provocation in the lung.42,44 Therefore, HRF/TCTP may exert additional enhancing effects through the eosinophil. Since an antibody to IL-5 has been shown to suppress eosinophil recruitment following OVA challenge in WT and FcɛRα−/− mice,44 giving anti-IL-5 to our OVA challenged HRF/TCTP mice could help determine HRF/TCTP’s mechanism upon eosinophil recruitment. Alternately, crossbreeding our HRF/TCTP transgenic mice with the eosinophil knockout PHIL mouse could ablate all HRF/TCTP-induced enhancing effects or affect only eosinophils. Future possibilities are numerous using this model as a tool.

Effects on SHIP1 and priming response of HRF/TCTP

That human basophils are cells capable of being “primed” or having an enhanced functional response has long been appreciated. Some of the molecules that are known to prime human basophils include IL-3, NGF, HRF/TCTP, and the non-physiologic stimulus D2O.38,45,46 In general, these substances show a greater releasability (as evidenced by histamine or IL-4 secretion) when stimulating basophils from allergic or allergic/asthmatic subjects. They do not generally activate basophils from normal subjects. The exception to this is the HRF/TCTP-R basophils. Basophils from these subjects are directly activated by D2O, IL-3, and HRF/TCTP.45,46

The molecular basis for the releasability of HRF/TCTP’s basophils remained elusive until relatively recently. It has become accepted that the term, releasability (ie, control of release of mediators from basophils in response to different stimuli) involves several biochemical events in addition to the surface density of IgE molecules. There have been reports of specific signaling molecule deficiencies in nonreleasing basophils.47,48 While these deficiencies are documented, there is little variation of SHIP-1 in the general population.49 We are the first group to show the negative association of the phosphatase, SHIP-1, with histamine release to HRF/TCTP in hyper releasing basophils.50 Variation of SHIP-1 levels has also been documented in a subset of patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria, in which levels of SHIP-1 were increased and anti-IgE-induced histamine release was reduced.51 Thus, SHIP-1 levels appear to be altered in some human disease states.

A clue to the underlying mechanisms of increased releasability of basophils was demonstrated in a mouse knockout of SHIP-1.52,53 Mast cells grown from the bone marrow of SHIP-1 knockout mice showed decreased hydrolysis of phosphatidyl-inositol (PI)-3,4,5,P3 (PIP3).53 SHIP-1 participates in the pathway in which the lipid phosphatidyl-inositol 4,5 bisphosphate is phosphorylated by PI3 kinase to produce PIP3, which can be acted upon to produce PI(3,4)bisphosphate.54,55 We have demonstrated that the compound LY294002, an inhibitor of PI3 kinase, inhibits histamine release induced by HRF/TCTP in basophils from HRF/TCTP-R donors.50 The activity of PI3 kinase is central to many basophil functions, and SHIP-1 acts to oppose the function of PI3 kinase by removing the 5′ phosphatase from PIP3, making SHIP-1 an important regulator of these reactions. Mouse SHIP-1 knockout mast cells exhibited an excess of PIP3 that resulted in a sustained calcium signal that was critical for degranulation.56 Furthermore, SHIP is a suppressor of IgE plus antigen-induced degranulation of not only bone marrow-derived mast cells, but also negatively regulates IgE plus antigen-induced degranulation of connective tissue and mucosal mast cells by repressing the P13 kinase pathway.57 Additionally, PIP3 recruits the serine tyrosine kinase, Akt, to the plasma membrane,58 which is present in human basophils and transiently phosphorylated after anti- IgE stimulation.59 Akt is phosphorylated by HRF/TCTP in HRF/TCTP-R donors but not in HRF/TCTP-NR donors.60 Furthermore, we see prolonged Akt phosphorylation kinetics in HRF/TCTP-R,60 which supports the involvement of this pathway in HRF induced activation. Data from the SHIP-1 knockout mice and our own published data suggest that SHIP-1 may play a “gatekeeper role” in mouse and human basophils and mast cells. One would expect SHIP-1 to limit effector cell responsiveness in normal individuals, while a SHIP-1 deficiency would predispose an individual to excess inflammatory-mediator production and, hence, a hyper releasable phenotype.

In order to address this more directly, we altered SHIP-1 levels in human basophils. These studies have been limited by the fact that the basophil is an end stage non-dividing cell and extremely difficult to transfect or transduce. Many attempts have been made to transfect primary human basophils. These include lipid based reagents, lentivirus, and nucleofection. Most failed either due to toxicity, or very low transfection efficiency. Only nucleofection (Amaxa, Lonza Inc, Allendale, NJ) gave a limited transfection efficiency that was useful only for single cell analysis.61 One report describes a TAT-fusion protein used for transfecting human basophils.62 We attempted to determine a more efficient method of altering signal transduction pathways in human basophils. To that end, we established a model of culturing human peripheral blood derived basophils from CD34+ cells that have the morphologic and functional characteristics of human basophils.63 We utilized this model to alter SHIP-1 levels using siRNA technology and demonstrated a decrease in SHIP-1 levels that was associated with an increase in histamine release to HRF/TCTP. Using CD34+ peripheral-derived basophils, it is possible to more directly test the hypothesis that SHIP-1 has a role in modulating basophil responsiveness, both to HRF/TCTP and IgE-mediated stimulation.

Intracellular signaling by HRF/TCTP

Another possible mechanism of action for HRF/TCTP may be IgE-dependent enhancement. Originally, HRF/TCTP was called the IgE-dependent HRF.4 This designation resulted from the fact that HRF seemed to act as a secretagogue for human basophils from a subpopulation of allergic donors. Moreover, passive sensitization of serum-containing IgE from these responding donors rendered non-responsive donors’ basophils responsive to HRF/TCTP.4 HRF/TCTP was then shown to activate other cells that do not possess the high-affinity IgE receptor, FcɛR1.17,19 We have demonstrated that HRF/TCTP has signal transduction events that are similar, but not identical, to signaling through FcɛR1.60 With the availability of both the FcɛR1α knockout mouse and the IgE knockout mouse,64,65 the question of whether HRF/TCTP is dependent on IgE can be definitively addressed. As mentioned, a manuscript has very recently been published demonstrating that mouse HRF/TCTP does bind to certain IgE and IgG molecules.18

In order to address the molecular mechanisms of HRF/TCTP-induced secretion, we designed experiments to elucidate specific actions of HRF/TCTP on human basophils and to characterize the nature of intracellular signaling that follows stimulation with HRF/TCTP. Given the similarities in secretion kinetics following IgE-mediated stimulation, we hypothesized there would be some signaling characteristics similar to those previously identified for IgE-mediated release. However, due to the differential sensitivity to treatment with rotterlin (Calbiochem Bering Corporation, La Jolla, CA) between HRF/TCTP and anti-IgE,15 we also expected differences in signaling. We used human basophils from two donor populations, HRF/TCTP-R and HRF/TCTP-NR. Consistent with the ability of HRF/TCTP to either induce secretion directly from HRF/TCTP-R basophils or prime HRF/TCTP-NR basophils, we used flow cytometry to show binding of HRF/TCTP to both donor populations.60 We demonstrated that HRF/TCTP induced activation of intracellular signal transduction events in basophils only from donors who directly release histamine to HRF/TCTP, namely, HRF/TCTP-R. Specifically, we demonstrated increases in the arachidonic acid metabolite leukotriene C4 (LTC4) from basophils of HRF/TCTP-R donors stimulated with anti-IgE. Additionally, we demonstrated LTC4 release from basophils stimulated with HRF/TCTP.60 One might predict that this might well be due to prolonged phosphorylation of MEK and extracellular signal-related kinases 1 and 2 (ERK1/2). Using human basophils isolated from leukopheresis packs, Miura et al demonstrated that activation of ERK1/2 is linked to arachodonic acid metabolism but not to histamine or IL-4 release.66 Phosphorylation of ERK1/2 is transient, peaks at 5 minutes, and returns to baseline by 30 minutes. We demonstrated that both MEK and ERK1/2 are phosphorylated by HRF/TCTP in basophils from HRF/TCTP-R donors but not from HRF/TCTP-NR donors.60 Thus, the characteristics of the signaling responses were very similar to those observed for stimulation with anti-IgE antibody or antigen with a few exceptions. Notably, no phosphorylation of FcɛR1γ was observed, and there was no phosphorylation of any downstream signal transduction molecules in the HRF/TCTP-NR basophils.

Clinical relevance of HRF/TCTP

HRF/TCTP’s link to human asthmatic, allergic disease has been well-accepted. It has been found in human respiratory secretions (BAL) and skin blister fluids.3 As not all donor’s basophils release histamine when exposed to HRF/TCTP, we conducted a study to define the responding population. Sixty-four ragweed allergic patients with a history of seasonal rhinitis and one or more positive skin tests were compared to 17 nonatopic control patients who were skin test negative. Sensitivity to HRF/TCTP was restricted to a subpopulation of atopic individuals.67 In a separate study of 55 ragweed allergic patients, there was a significant correlation between the intensity of symptoms in the late phase reaction and basophil histamine release to HRF/TCTP.68 In studies from another group, peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with asthma spontaneously produced HRF/TCTP.69,70 Production of HRF/TCTP not only correlated with bronchial hyperreactivity but bronchial sensitivity to methacholine of the patient correlated with the magnitude of HRF/TCTP production.71 Sampson et al showed that production of HRF/TCTP also is associated with clinical status of food allergy and atopic dermatitis. 72 Using blood from food allergic children with atopic dermatitis, they found that their basophils have a high spontaneous release of histamine and their cultured mononuclear cells spontaneously produce HRF/TCTP. When these children were placed on an avoidance diet, they improved clinically, their basophils no longer spontaneously secreted histamine, and their mononuclear cells no longer spontaneously produced HRF/TCTP. Two groups have reported the effects of immunotherapy on HRF/TCTP production. One group showed a striking correlation between the production of HRF/TCTP by mononuclear cells and the change in bronchial sensitivity to histamine (PC20) after two years of immunotherapy.73 Brunet et al showed that immunotherapy in allergic rhinitis patients without asthma improved symptoms and prevented the seasonal increase of spontaneous and antigen-driven HRF/TCTP production from peripheral blood mononuclear cells.74 Moreover, we measured HRF in human BAL fluids of allergics following antigen challenge. While HRF/TCTP increases over baseline after antigen challenge, it is not significant considering the number of patients (n = 8) investigated (unpublished observations).

With the availability of recombinant material, we examined the generation of HRF/TCTP mRNA and protein in the lymphocytes of allergic and non-allergic patients. Twelve patients (four HRF/TCTP-R, four HRF/TCTP-NR, and four non-allergic patients) were recruited. Blood was drawn for serum IgE measurements and for basophil histamine release in response to recombinant HRF/TCTP and anti-IgE. In addition, peripheral blood mononuclear cells were cultured for HRF/TCTP production and processed for mRNA extraction and subsequent reverse transcription PCR for HRF/TCTP mRNA. The geometric mean serum IgE levels were 356 ng mL−1 in the HRF/TCTP-R group versus 52 μg mL−1 and 4.2 μg mL−1 in HRF/TCTP-NR and non-allergic subjects, respectively. Histamine release in response to the recombinant HRF/TCTP paralleled that of our native HRF/TCTP preparation in that only the four HRF/TCTP-R patients released histamine to this stimulus. The quantity of mRNA for HRF/TCTP, when compared to that for beta actin, the housekeeping gene, did not appear different among the groups. The bioactivity of the recombinant HRF/TCTP on lactic acid-treated cells passively sensitized with an IgE containing serum from a HRF/TCTP-R, however, was greater in the allergic HRF/TCTP-R patients than in non-allergic subjects.75,76 Thus, it appears that all individuals produce mRNA for HRF/TCTP but that atopic subjects more effectively translate it into protein. In a very recent abstract, serum from some patients with atopic dermatitis, but not normal patients, showed increased levels of HRF/TCTP-reactive IgE levels.77 These atopic dermatitis patients’ sera could cause cytokine secretion from human mast cells.77

HRF/TCTP as a therapeutic target

Based on the above observations, HRF/TCTP may be an important element of the pathogenesis of asthmatic, allergic diseases. Since HRF/TCTP is present in late phase reaction fluids in vivo, it may be contributing to mediator release observed during the late response. Therefore, it is reasonable to consider HRF as a therapeutic target. The most direct way to demonstrate that HRF/TCTP is a therapeutic target would be to block its binding to its receptor. However, despite numerous attempts by different laboratories, the HRF/TCTP receptor has remained elusive. An HRF/TCTP-blocking antibody would prove useful in this approach. Unfortunately, no specific antibody exists. A recent publication demonstrated that the extracellular actions of HRF/TCTP can be explained, at least in part, by specific binding sequences on mHRF to some IgE and IgG molecules.18 In two regions, the N-terminal 19-residue peptide and residues 107–135, the H3 region, were found to be important for this binding to immunoglobulins.78 These regions overlapped only in part with the antigen binding site. Furthermore, some, but not all, IgE and IgE molecules supported or bound to HRF/TCTP.18 Nevertheless, this observation warrants further investigation.

Two additional observations remain. The possibility exists that this HRF/TCTP-immunoglobulin interaction can be explained by nonspecific ionic interactions or interactions of different parts of the immunoglobulins. Moreover, BAL and sera from naïve mice contain HRF/TCTP that does not normally yield inflammation.18 This suggests that there may be a suppressive mechanism of inflammation induced by endogenous HRF/TCTP. Our own SHIP data with the inverse correlation of levels of SHIP-1 protein with histamine release to HRF/TCTP would support this.50

Ong et al discovered small molecule agonists of SHIP-1 that inhibit the P13K pathway.78 These are potent and specific activators of SHIP-1. Initial mouse model studies suggested that these agonists may be therapeutically useful. Our laboratory received such an agonist and was able to demonstrate that anti-IgE-induced basophil histamine release was inhibited, while F-met leu-ple-induced release was not (data not shown). In fact, it was recently reported at the American Thoracic Society Meeting in May 2012 in San Francisco that the SHIP-1 agonist, AQX-1125 from Aquinox Pharmaceuticals, was tested in a three-part Phase I study that included a single ascending dose, a multiple ascending dose, and a food effect study in health human volunteers.79 The drug was well-tolerated and had a half-life that supported a once-daily oral administration. These studies will progress into Phase IIa for experimental therapy of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma.79 These promising results will be followed with interest. It should be noted that part of the content, but not all of this review, was written by Susan MacDonald and published in the Open Allergy Journal.80

Summary

In conclusion, further defining the extracellular role of the mechanism of HRF/TCTP-induced priming in vivo using our HRF/TCTP inducible transgenic mouse and in vitro using both peripheral blood-derived basophils and CD34+-peripheral derived cultured basophils may yield additional insight into HRF/TCTP’s participation in the propagation of the Th2 asthmatic allergic response. Successful completion of these studies may lead to inhibition of this unique cytokine’s function and amelioration of its role in allergic, asthmatic diathesis. SHIP-1 agonists may be useful as therapeutic targets for the actions of HRF/TCTP in allergic responses.

Acknowledgment

Special thanks to Ms Nancy Van Keuren for technical assistance and Aquinox Pharmaceutical, Inc Members of the Scientific Advisory Board.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The author is a member of the Scientific Advisory Board of Aquinox Pharmaceuticals Inc.

References

- 1.Yenofsky R, Cereghini S, Krowczynska A, Brawerman G. Regulation of mRNA utilization in mouse erythroleukemia cells induced to differentiate by exposure to dimethyl sulfoxide. Mol Cell Biol. 1983;3(7):1197–1203. doi: 10.1128/mcb.3.7.1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chitpatima ST, Makrides S, Bandyopadhyay R, Brawerman G. Nucleotide sequence of a major messenger RNA for a 21 kilodalton polypeptide that is under translational control in mouse tumor cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16(5):2350. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.5.2350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MacDonald SM, Lichtenstein LM, Proud D, Plaut M, Naclerio RM, Kagey-Sobotka A. Studies of IgE-dependent histamine releasing factors: Heterogeneity of IgE. J Immunol. 1987;139(2):506–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacDonald SM, Rafnar T, Langdon J, Lichtenstein LM. Molecular identification of an IgE-dependent histamine releasing factor. Science. 1995;269(5224):688–690. doi: 10.1126/science.7542803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacDonald SM, Bhisutthibhan J, Shapiro TA, et al. Immune mimicry in malaria: Plasmodium falciparum secretes a functional histamine-releasing factor homolog in vitro and in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(19):10829–10832. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201191498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gnanasekar M, Rao KV, Chen L, et al. Molecular characterization of a calcium binding translationally controlled tumor protein homologue from the filarial parasites Brugia malayi and Wuchereria bancrofti. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2002;121(1):107–118. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(02)00027-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rao KV, Chen L, Gnanasekar M, Ramaswamy K. Cloning and characterization of a calcium-binding histamine-releasing protein from Schistosoma mansoni. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(34):31207–31213. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204114200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Langdon JM, Vonakis BM, MacDonald SM. Identification of the interaction between the human recombinant histamine releasing factor/translationally controlled tumor protein and elongation factor-1 delta (also known as eElongation factor-1B beta) Biochem Biophys Acta. 2004;1688(3):232–236. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cans C, Passer BJ, Shalak V, et al. Translationally controlled tumor protein acts as a guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitor on the translation elongation factor eEF1A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(24):13892–13897. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2335950100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amzallag N, Passer BJ, Allanic D, et al. TSAP6 facilitates the secretion of translationally controlled tumor protein/histamine-releasing factor via a nonclassical pathway. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(44):46104–46112. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404850200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moldes M, Lasnier F, Gauthereau X, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced adipose-related protein (TIARP), a cell-surface that is highly induced by tumor necrosis factor-alpha and adipose conversion. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(36):33938–33946. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105726200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Korkmaz KS, Elbi C, Korkmaz CG, Loda M, Hager GL, Saatcioglu F. Molecular cloning and characterization of STAMP1, a highly prostate-specific six transmembrane protein that is overexpressed in prostate cancer. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(39):36689–36696. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202414200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schroeder JT, Lichtenstein LM, MacDonald SM. An immunoglobulin E-dependent recombinant histamine releasing factor induces IL-4 secretion from human basophils. J Exp Med. 1996;183(3):1265–1270. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.3.1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schroeder JT, Lichtenstein LM, MacDonald SM. Recombinant histamine- releasing factor enhances IgE-dependent IL-4 and IL-13 secretion by human basophils. J Immunol. 1997;159(1):447–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bheekha-Escura R, Chance SR, Langdon JM, MacGlashan DW, Jr, MacDonald SM. Pharmacologic regulation of histamine release by the human recombinant histamine-releasing factor. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;103(5 Pt 1):937–943. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70442-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wantke F, MacGlashan DW, Jr, Langdon JM, MacDonald SM. The human recombinant histamine releasing factor: functional evidence that it does not bind to the IgE molecule. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;103(4):642–648. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70237-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bheekha-Escura R, MacGlashan DW, Jr, Langdon JM, MacDonald SM. Human recombinant histamine-releasing factor activates human eosinophils and the eosinophilic cell line, AML14-13D10. Blood. 2000;96(6):2191–2198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kashiwakura J, Ando T, Matsumoto K, et al. Proinflammatory role of histamine-releasing factor in mouse models of asthma and allergy. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(1):218–228. doi: 10.1172/JCI59072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vonakis BM, Sora R, Langdon JM, Casolaro V, MacDonald SM. Inhibition of cytokine gene transcription by the human recombinant histamine-releasing factor in human T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2003;171(7):3742–3750. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.7.3742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kang HS, Lee MJ, Song H, et al. Molecular identification of IgE-dependent histamine-releasing factor as a B cell growth factor. J Immunol. 2001;166(11):6545–6554. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.11.6545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoneda K, Rokutan K, Nakamura Y, Yanagawa H, Kondo-Teshima S, Sone S. Stimulation of human bronchial epithelial cells by IgE-dependent histamine-releasing factor. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;286(1):L174–L181. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00118.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu A, Bellamy AR, Taylor JA. Expression of translationally controlled tumour protein is regulated by calcium at both the transcriptional and post-transcriptional level. Biochem J. 1999;342(Pt 3):683–689. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gachet Y, Tournier S, Lee M, Lazaris-Karatzas A, Poulton T, Bommer UA. The growth-related, translationally controlled protein P23 has properties of a tubulin binding protein and associates transiently with microtubules during the cell cycle. J Cell Sci. 1999;112(Pt 8):1257–1271. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.8.1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rid R, Onder K, Trost A, et al. H2O2-dependent translocation of TCTP into the nucleus enables its interaction with VDR in human keratinocytes: TCTP as a further module in calcitriol signalling. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;118(1–2):29–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2009.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fenner BJ, Scannell M, Prehn JH. Expanding the substantial inter-actome of NEMO using protein microarrays. PLoS One. 2010;5(1):e8799. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang D, Li F, Weidner D, Mnjoyan ZH, Fujise K. Physical and functional interaction between myeloid cell leukemia 1 protein (MCL1) and Fortilin. The potential role of MCL1 as a fortilin chaperone. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(40):37430–37438. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207413200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang Y, Yang F, Xiong Z, et al. An N-terminal region of translationally controlled tumor protein is required for its antiapoptotic activity. Oncogene. 2005;24(30):4778–4788. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arcuri F, Papa S, Carducci A, et al. Translationally controlled tumor protein (TCTP) in the human prostate and prostate cancer cells: expression, distribution, and calcium binding activity. Prostate. 2004;60(2):130–140. doi: 10.1002/pros.20054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vercoutter-Edouart AS, Czeszak X, Crépin M, et al. Proteomic detection of changes in protein synthesis induced by fibroblast growth factor-2 in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. Exp Cell Res. 2001;262(1):59–68. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.5066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chung S, Kim M, Choi W, Chung J, Lee K. Expression of translationally controlled tumor protein mRNA in human colon cancer. Cancer Lett. 2000;156(2):185–190. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(00)00460-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tuynder M, Fiucci G, Prieur S, et al. Translationally controlled tumor protein is a target of tumor reversion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(43):15364–15369. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406776101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li F, Zhang D, Fujise K. Characterization of fortilin, a novel antiapoptotic protein. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(50):47542–47549. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108954200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Susini L, Besse S, Duflaut D, et al. TCTP protects from apoptotic cell death by antagonizing bax function. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15(8):1211–1220. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rho SB, Lee JH, Park MS, et al. Anti-apoptotic protein TCTP controls the stability of the tumor suppressor p53. FEBS Lett. 2011;585(1):29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Amson R, Pece S, Lespagnol A, et al. Reciprocal repression between P53 and TCTP. Nat Med. 2011;18(1):91–99. doi: 10.1038/nm.2546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen SH, Wu PS, Chou CH, et al. A knockout mouse approach reveals that TCTP functions as an essential factor for cell proliferation and survival in a tissue- or cell type-specific manner. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18(7):2525–2533. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-02-0188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yueh-Chiao Y, Xie L, Langdon JM, et al. The effects of overespression of histamine releasing factor (HRF) in a transgenic mouse model. PloS ONE. 2010;5(6):e11077. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schroeder JT. Basophils: Beyond effector cells of allergic inflammation. Adv Immunol. 2009;101:123–161. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(08)01004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seder RA, Paul WE, Dvorak AM, et al. Mouse splenic and bone marrow cell populations that express high-affinity Fc epsilon receptors and produce interleukin 4 are highly enriched in basophils. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88(77):2835–2839. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.7.2835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Min B, Paul W. Basophils and type 2 immunity. Curr Opin Hematol. 2008;15(1):59–63. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e3282f13ce8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Obata K, Mukai K, Tsujimura Y, et al. Basophils are essential initiators of a novel type of chronic allergic inflammation. Blood. 2007;110(3):913–920. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-068718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jacobsen EA, Ochkur SI, Pero RS, et al. Allergic pulmonary inflammation in mice is dependent on eosinophil-induced recruitment of effector T cells. J Exp Med. 2008;205(3):699–710. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee JJ, Dimina D, Macias MP, et al. Defining a link with asthma in mice congenitally deficient in eosinophils. Science. 2004;305(5691):1773–1776. doi: 10.1126/science.1099472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mayr SI, Zuberi RI, Zhang M, et al. IgE-dependent mast cell activation potentiates airway responses in murine asthma models. J Immunol. 2002;169(4):2061–2068. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.4.2061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.MacDonald SM, White JM, Kagey-Sobotka A, MacGlashan DW, Jr, Lichtenstein LM. The heterogeneity of human IgE exemplified by the passive transfer of D2O sensitivity. Clin Exp Allergy. 1991;21(1):133–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1991.tb00815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.MacDonald SM, Schleimer RP, Kagey-Sobotka A, Gillis S, Lichtenstein LM. Recombinant IL-3 induces histamine release from human basophils. J Immunol. 1989;142(10):3527–3532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kepley CL, Youssef L, Andrews RP, Wilson BS, Oliver JM. Syk deficiency in nonreleaser basophils. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;104(2 Pt 1):279–284. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70367-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lavens-Phillips SE, MacGlashan DW., Jr The tyrosine kinases p563/56lyn and p72 syk are differentially expressed at the protein level but not at the messenger RNA level in nonreleasing human basophils. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2000;23(4):566–571. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.23.4.4123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vilariño N, Miura K, MacGlashan DW., Jr Acute IL-3 priming up-regulates the stimulus-induced Raf-1-Mek-Erk cascade independently of IL-3-induced activation of Erk. J Immunol. 2005;175(5):3006–3014. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.5.3006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vonakis BM, Gibbons S, Jr, Sora R, Langdon JM, MacDonald SM. Src homology 2 domain-containing inositol 5’ phosphatase is negatively associated with histamine release to human recombinant histamine releasing factor in human basophils. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108(5):822–831. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.119159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vonakis BM, Vasagar K, Gibbons SP, Jr, et al. Basophil FcepsilonRI histamine release parallels expression of Src-homology 2-containing inositol phosphatases in chronic idiopathic urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119(2):441–448. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Krystal G. Lipid phosphatases in the immune system. Immunology. 2000;12(4):397–403. doi: 10.1006/smim.2000.0222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huber M, Helgason CD, Damen JE, et al. The src homology 2 containing inositol phosphatase (SHIP) is the gatekeeper of mast cell degranulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(19):11330–11335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rohrschneider LR, Fuller JF, Wolf I, Liu Y, Lucas DM. Structure, function and biology of SHIP proteins. Genes Dev. 2000;14(5):505–520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Scharenberg AM, Kinet J-P. PtdIns-3,4,5-P3: a regulatory nexus between tyrosine kinases and sustained calcium signals. Cell. 1998;94(1):5–8. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lioubin MN, Algate PA, Tsai S, Carlberg K, Aebersold A, Rohrschneider LR. p150Ship, a signal transduction molecule with inositol polyphosphate-5-phosphatase activity. Genes Dev. 1996;10(9):1084–1095. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.9.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ruschmann J, Antignano F, Lam V, et al. The role of SHIP in the development and activation of mouse mucosal and connective tissue mast cells. J Immunol. 2012;188(8):3839–3850. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brauweiler AM, Tamir I, Cambier JC. Bilevel control of B-cell activation by the inositol 5-phosphatase SHIP. Immunol Rev. 2000;176:69–74. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2000.00612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Miura K, Lavens-Phillips S, MacGlashan DW., Jr Localizing a control region in the pathway to LTC4 secretion following stimulation of human basophils with anti-IgE antibody. J Immunol. 2001;167(12):7027–7037. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.12.7027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vonakis BM, MacGlashan DW, Jr, Vilariño N, Langdon JM, Scott RS, MacDonald SM. Distinct characteristics of signal transduction events by histamine releasing factor/translationally controlled tumor protein (HRF/TCTP)-induced priming and activation of human basophils. Blood. 2008;111(4):1789–1796. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-104364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vilariño N, MacGlashan D., Jr Transient transfection of human peripheral blood basophils. J Immunol Meth. 2005;296(1–2):11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Didichenko SA, Spiegl N, Brunner T, Dahinden CA. IL-3 induces a Pim1-dependent antiapototic pathway in primary human basophils. Blood. 2008;112(10):3949–3958. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-149419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Langdon JM, Schroeder JT, Vonakis BM, Bieneman AP, Chichester K, MacDonald SM. Histamine-releasing factor/translationally controlled tumor protein (HRF/TCTP)-induced histamine release is enhanced with SHIP-1 knockdown in cultured human mast cell and basophil models. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;84(4):1151–1158. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0308172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dombrowicz D, Flamand V, Brigman KK, Koller BH, Kinet JP. Abolition of anaphylaxis by targeted disruption of the high affinity immunoglobulin E receptor alpha chain gene. Cell. 1993;75(5):969–976. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90540-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Oettgen HC, Martin TR, Wynshaw-Boris A, Deng C, Drazen JM, Leder P. Active anaphylaxis in IgE-deficient mice. Nature. 1994;370(6488):367–370. doi: 10.1038/370367a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Miura K, Schroeder JT, Hubbard WC, MacGlashan DW., Jr Extracellular signal-regulated kinases regulate leukotriene C4 generation, but not histamine release or IL-4 production from human basophils. J Immunol. 1999;162(7):4198–4206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.MacDonald SM, Kagey-Sobotka A, Proud D, Naclerio RM, Lichtenstein LM. Histamine-releasing factor: release mechanism and responding population. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1987;79:248. [Google Scholar]

- 68.MacDonald SM. Histamine releasing factors and IgE heterogeneity. In: Middleton E, Reed CE, Ellis EF, Adkinson NF, Yunginger JW, Buss WW, editors. Allergy: Principles and Practice. 4th Edition. 1993. pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Alam R, Rozniecki J, Salmaj K. A mononuclear cell derived histamine releasing factor (HRF) in asthmatic patients. Histamine release from basophils in vitro. Ann Allergy. 1984;53(1):66–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Alam R, Rozniecki J. A mononuclear cell-derived histamine releasing factor in asthmatic patients. II. Activity in vivo. Allergy. 1985;40(2):124–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1985.tb02671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Alam R, Kuna P, Rozniecki J, Kuzminska B. The magnitude of the spontaneous production of histamine-releasing factor (HRF) by lymphocytes in vitro correlates with the state of bronchial hyperreactivity in patients with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1987;79(1):103–108. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(87)80023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sampson HA, Broadbent KR, Bernhisel-Broadbent J. Spontaneous release of histamine from basophils and histamine-releasing factor in patients with atopic dermatitis and food hypersensitivity. N Engl J Med. 1989;321(4):228–232. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198907273210405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kuna P, Alam R, Kuzminska B, Rozniecki J. The effect of preseasonal immunotherapy on the production of histamine-releasing factor (HRF) by mononuclear cells from patients with seasonal asthma: results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1989;83(4):816–882. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(89)90020-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Brunet C, Bédard PM, Lavoie A, Jobin M, Hébert J. Allergic rhinitis to ragweed pollen. II. Modulation of histamine-releasing factor production by specific immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1992;89(1 Pt 1):87–94. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(05)80044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.MacDonald SM. Histamine-releasing factors. Curr Opi Immunol. 1996;8(6):778–783. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(96)80004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Langdon J, Anders K, Lichtenstein LM, MacDonald SM. Atopics translate mRNA for the IgE-dependent histamine releasing factor (HRF) more effectively than normal. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1995;95:336. (Abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ando T, Kashiwakura J, Kawakami Y, Kawakami T. Histamine releasing factor (HRF) in asthma and atopic dermatitis. J Immunol. 2012;188:177.16. (Abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ong CJ, Ming-Lum A, Nodwell M, et al. Small-molecule agonists of SHIP1 inhibit the phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway in hematopoietic cells. Blood. 2007;110(6):1942–1949. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-079699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tam P, Mackenzie LF, Toews J, et al. Absorption, pharmacokinetics, metabolism, distribution and tolerability of AQX-1125, a SHIP1 activator clinical development candidate, in healthy humans volunteers: comparison with dogs and rats. ATS Abstract. 2012 May; [Google Scholar]

- 80.MacDonald SM. Histamine releasing factor/translational controlled tumor protein: history, functions and clinical implications. Open Allergy Journal. 2012;5:12–18. [Google Scholar]