Abstract

Hyperpigmentary disorders, especially melasma and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH), cause significant social and emotional stress to the patients. Although many treatment modalities have been developed for melasma and PIH, its management still remains a challenge due to its recurrent and refractory nature. With the advent of laser technology, the treatment options have increased especially for dermal or mixed melasma. To review the literature on the use of cutaneous lasers for melasma and PIH. We carried out a PubMed search using following terms “lasers, IPL, melasma, PIH”. We cited the use of various lasers to treat melasma and PIH, including Q-switched Nd:YAG, Q-switched alexandrite, pulsed dye laser, and various fractional lasers. We describe the efficacy and safety of these lasers for the treatment of hyperpigmentation. Choosing the appropriate laser and the correct settings is vital in the treatment of melasma. The use of latter should be restricted to cases unresponsive to topical therapy or chemical peels. Appropriate maintenance therapy should be selected to avoid relapse of melasma.

KEYWORDS: Fractional, hyperpigmentation, lasers, melasma

INTRODUCTION

Lasers have revolutionized the treatment of many dermatological conditions. One of these is the pigmentary disorders. Lasers have been widely used with variable success for the treatment of pigmented conditions which include Becker's nevus, cafe-au-lait macules, Nevus of Ota, nevocellular nevi, lentigines, tattoos, melasma, and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH). Although many pigmentary disorders have shown good results with laser treatment, the efficacy and safety of lasers for melasma is still controversial. In this review, we will discuss the various lasers that have been tried in melasma and PIH.

Our review was based on articles where laser and intense pulsed light (IPL) have been used for melasma and PIH. This was done by carrying out a PubMed search using following terms “lasers, IPL, melasma, PIH.” We studied the various settings used and the side effects seen with various lasers like QS Nd:YAG, QS Ruby, alexandrite, and various fractional lasers. We will also discuss the role of lasers for PIH. As this condition is the side effect of laser treatment itself, its management still remains a challenge.

OVERVIEW OF LASERS

Lasers (Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation) are sources of high-intensity monochromatic coherent light that can be used for the treatment of various dermatologic conditions depending on the wavelength, pulse characteristics, and fluence of the laser being used and the nature of the condition being treated. Also, high-intensity incoherent and multichromatic light (IPL) can be used for similar indications.

Laser treatment of pigmented lesions is based on the theory of Selective Photothermolysis proposed by Anderson and Parrish, which states that when a specific wavelength of energy is delivered in a period of time shorter that the thermal relaxation time (TRT) of the target chromophore, the energy is restricted to the target and causes less damage to the surrounding tissue.[1] Hence, a laser should emit a wavelength that is specific and well absorbed by the particular chromophore being treated. A selective window for targeting melanin lies between 630 and 1100 nm, where there is good skin penetration and preferential absorption of melanin over oxyhaemoglobin.[2] Absorption for melanin decreases as the wavelength increases, but a longer wavelength allows deeper skin penetration. Shorter wavelengths (<600 nm) damage pigmented cells with lower energy fluencies, while longer wavelengths (>600 nm) penetrate deeper but need more energy to cause melanosome damage.

Besides wavelength, pigment specificity of lasers also depends on pulse width.[2] With an estimated TRT of 250–1000 ns, melanosomes require submicrosecond laser pulses (<1 μs) for their selective destruction, but longer pulse durations in the millisecond domain do not appear to cause specific melanosome damage.[2]

Lasers have been tried in the treatment of various pigmentary disorders with variable success. However, this review will focus on laser treatment of melasma and PIH which are perhaps the commonest pigmentary disorders seen in practice

Various lasers that have been used for melasma include the following[3]:

Green light: flashlamp-pumped pulsed dye laser (PDL) (510 nm), frequency doubled QS Nd:YAG (Q Switched Neodymium: Yttrium Aluminium Garnet-532 nm)

Red light: QS Ruby (694 nm), QS Alexandrite (755 nm)

Near-infrared: QS Nd:YAG (1064 nm)

The green light lasers do not penetrate as deeply into the skin as the other two groups owing to their shorter wavelengths. They are therefore effective only in the treatment of epidermal melasma.

Since the green wavelength is also well absorbed by oxyhaemoglobin, bruising and purpura may occur following laser irradiation. The purpura resolves in 1–2 weeks after treatment, and the clinical lesions lighten in 4–8 weeks. Occasionally, the bruising can lead to PIH.[2] Green light lasers often have a variable response and thus test spots may be prudent prior to treating the whole area.[3]

Red lasers have longer wavelengths and thus may penetrate deeper into the dermis. They can also be used to treat epidermal pigmented lesions without bruising as they are not absorbed by haemoglobin.[2] The pulse duration of the QS ruby laser varies from 20 to 50 ns and that of QS Alexandrite laser from 50 to 100 ns. Besides selective photothermolysis, these lasers also lead to photoacoustic mechanical disruption of melanin caused by rapid thermal tissue expansion.

Near-infrared lasers include QS Nd:YAG laser (1064 nm) which has a pulse duration of 10 ns. Despite less absorption of this wavelength by melanin compared with the green and red light lasers, its advantage lies in its ability to penetrate more deeply in the skin. In addition, it may prove to be more useful in the treatment of lesions in individuals with darker skin tones.[3]

Both lasers and IPL have been used in treatment of melasma. The field of laser surgery has been revolutionized by the introduction of the concept of fractional photothermolysis by Manstein and Anderson.[4] Fractional photothermolysis involves emission of light into microscopic treatment zones , hence creating small columns of injury to the skin and sparing the surrounding untreated skin. The downtime and side effects are less with these fractional lasers operating through this concept of FP. Fractional lasers have been used for the treatment of a variety of pigmented lesions including melasma,[5,6] Becker's nevus,[7] nevus of Ota,[8] and PIH.[9,10]

Pre-operative preparation

History: allergy to topical anaesthetic, medical condition, treatment (H/O isotretinoin use), H/O herpes labialis

Strict sun avoidance

Topical depigmenting agents: pre- and post-treatment

Informed consent

Pre-treatment photographs

Test spots (for Q-switched lasers)

Counsel patients accordingly to expect reasonable results

Appropriate eye protection, eye shields, universal precautions

MELASMA AND LASERS

Melasma is an acquired pigmentary disorder characterized by brownish hyperpigmented macules usually on the face. Majority of the cases are seen in women, although 10% of the cases are males. The etiopathogenesis of melasma involves an interplay of various factors such as sunexposure, hormonal factors (pregnancy and oral contraceptive pills), genetic predisposition, and phototoxic drugs. Association has also been found with ovarian dysfunction, thyroid autoimmune disease, liver disease, and cosmetics.[11–13]

Melasma can be classified based on the site of the lesions (craniofacial, malar, mandibular), histological depth of pigmentation (epidermal, dermal, mixed), and appearance under the Wood's lamp (epidermal, dermal, mixed, indeterminate).[11,14]

The recurrent and refractory nature of this condition makes it difficult for treatment. Current treatment strategies include medical treatment (triple combination therapy or modified Kligman's regime, hydroquinone, kojic acid, azelaic acid, and vitamin C), chemical peeling, and laser therapy including IPL.

Q SWITCHED LASERS

The TRT of melanosomes ranges from 50 to 500 ns and absorption spectrum of melanin is broad. Q switched lasers (Q Switched Nd:YAG, Q Switched Ruby, Q Switched Alexandrite laser) deliver nanosecond pulse duration, hence they selectively target melanosomes with thermal diffusion.

Q S ND:YAG

The 1064 nm QS-Nd:YAG is well absorbed by melanin and being a longer wavelength causes minimal damage to epidermis and is not absorbed by haemoglobin. The deeper skin penetration is also helpful to target dermal melanin. Low-dose QS Nd:YAG laser induces sublethal injury to melanosomes causing fragmentation and rupture of melanin granules into the cytoplasm.[1,15] This effect is highly selective for melanosomes as this wavelength is well absorbed by melanin relative to other structures. There is also subcellular damage to the upper dermal vascular plexus which is one of the pathogenetic factors in melasma.[16] The subthreshold injury to the surrounding dermis stimulates the formation of collagen resulting in brighter and tighter skin.[17]

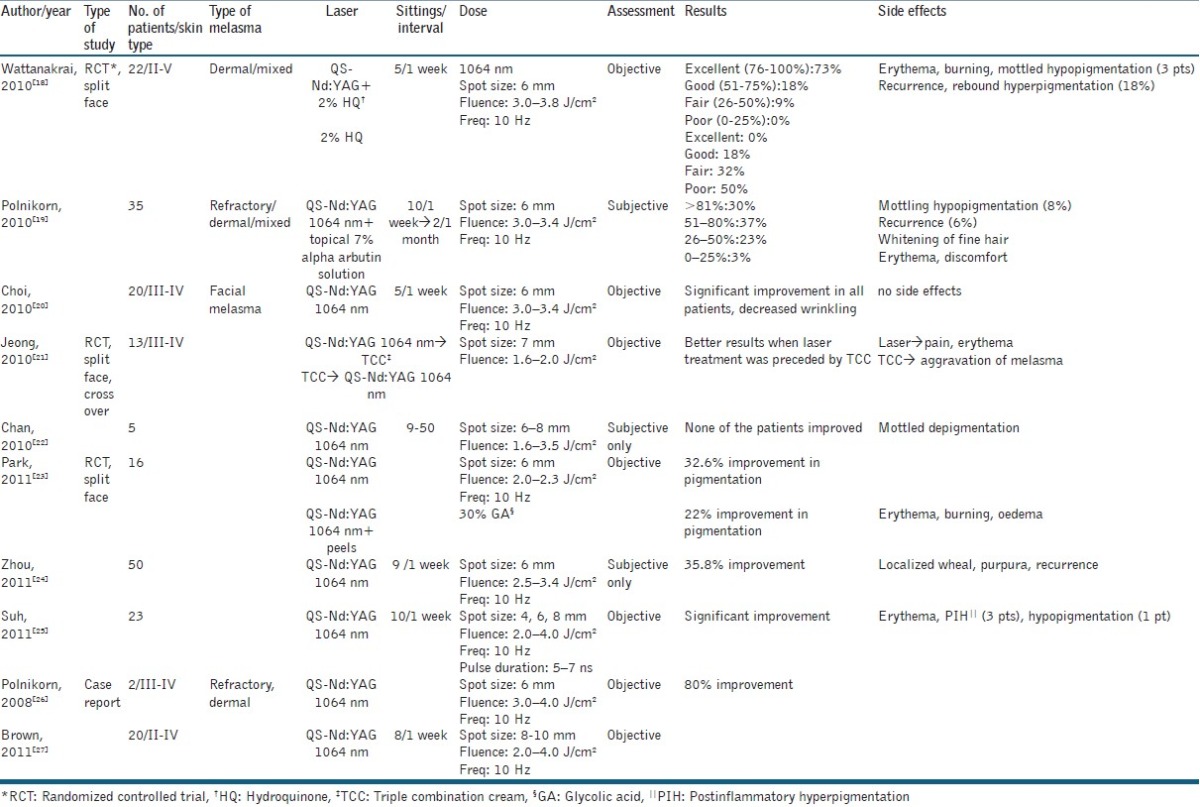

QS-Nd:YAG is the most widely used laser for the treatment of melasma. Various studies[18–27] done with this laser are summarized in Table 1. The fluence used is less than 5 J/cm2, spot size 6 mm, and frequency of 10 Hz. The number of treatment sessions varies from 5 to 10 at 1-week intervals.

Table 1.

Summary of studies using QS-Nd:YAG (1064 nm) laser for melasma

In a randomized controlled trial conducted by Wattanakrai et al.,[18] 22 patients with dermal or mixed melasma were treated with same laser at fluence of 3.0–3.8 J/cm2 for five sessions at 1-week interval. The treatment was combined with 2% hydroquinone and compared with hydroquinone alone. There was 92.5% improvement that was significant compared to the control group. However, in this study 13.6% patients developed faint, spotty hypopigmentation that improved during follow-up. Also, 18% patients developed rebound hyperpigmentation and all patients had recurrence of melasma.

Zhou and colleagues treated 50 patients of melasma with 1064-nm QS Nd:YAG laser at low energy levels (fluence of 2.5–3.4 J/cm2) weekly for nine sessions and found 35.8% improvement from baseline.[24] The authors also studied various factors affecting outcome and concluded that therapeutic outcome depended on disease severity at baseline.

Jeong et al. compared the clinical efficacy and adverse effects of low fluence Q switched Nd:YAG (1064 nm) laser when performed before and after treatment with topical triple combination creams (TCCs) using a split face crossover design in 13 patients with melasma.[21] They used a collimated, 5–7 ns pulse width, 7 mm spot size, and a fluence of 1.6–2.0 J/cm2. Weekly sessions were done for 8 weeks. Laser was compared with pre- or post-treatment TCC. The authors found that pre-treatment with TCCs was more effective as this decreases melanin production before laser injury, hence chances of PIH are reduced and the melasma is improved. If TCC is used after laser treatment, melanin is being produced at full capacity, hence increasing chances of PIH and slowing improvement of melasma. Hence, the authors recommend medical treatment for hyperpigmentation for at least 8 weeks before laser treatment to achieve optimal results.

This technique used in the above studies has recently been referred to as “laser toning” or “laser facial” and has become increasingly popular. It is widely used in Asian countries for skin rejuvenation and melasma. Laser toning involves the use of a large spot size (6–8 mm), low fluence (1.6–3.5 J/cm2), multiple passed QS 1064 nm Nd:YAG laser performed every 1-2 weeks for several weeks.[22] While few studies document good efficacy with this Technique,[26,28] several others have found hypopigmentation and depigmentation after a series of laser toning.[18,22,29] Chan et al. treated five Chinese patients with melasma with laser toning.[22] There was no significant improvement in melasma and all five patients developed laser-induced depigmentation. Possible pathogenic mechanisms for this depigmentation could be high fluences causing direct phototoxicity and cellular destruction of melanocyte, subthreshold additive effect of multiple doses, intrinsic unevenness of skin pigmentation, and non-uniform laser energy output.[22] Several other side effects mentioned in the literature include rebound hyperpigmentation, physical urticaria, acneiform eruption, petechiae, and herpes simplex reactivation. Rebound hyperpigmentation could be due to the multiple subthreshold exposures that can stimulate melanogenesis in some areas.

Whitening of fine hair can also occur due to follicular depigmentation. Anderson et al.[30] conducted a study in guinea pigs to examine the effects of selective photothermolysis of cutaneous pigmentation using QS Nd:YAG laser after single-pulse exposures at 1064, 532, and 355 nm in guinea pigs. They found that only 532 and 1064 nm at threshold and suprathreshold dose produced permanent leukotrichia. At subthreshold exposure, none of these wavelengths caused hypopigmentation but they accelerated melanogenesis.

To avoid serious side effects, it is recommended that too many (>6-10) or too frequent (every week) laser sessions with QS Nd:YAG should be avoided. Hypopigmentation should be looked for after every session and further treatments should be stopped.

Few studies have been carried out to assess the safety of lasers and their effect on tumorigenesis. Chan et al.[31] studied the effect of repeated treatments with high-energy laser and IPL exposure on animals and found elevations of p16 and proliferating cell nuclear antigen expression indicating DNA damage. In another in vitro study examining the effect of sublethal QS 755 nm lasers on the expression of p16 INK4a on melanoma cell lines, it was found that laser exposure could increase DNA damage leading to greater p16 expression.[32]

Q SWITCHED RUBY LASER

The efficacy of Q Switched Ruby Laser (QSRL) for melasma is still controversial. The mechanism is the same as that of QS Nd:YAG laser, that is, it causes highly selective destruction of melanosomes. QS Ruby laser, being a wavelength of 694 nm, is more selective for melanin than the QS Nd:YAG laser(1064 nm).

So theoretically QSRL is expected to be more effective than QS Nd:YAG for melasma. Tse Y and colleagues compared the efficacy and side effect profile of the QSRL and 1064 QS Nd:YAG in the removal of cutaneous pigmented lesions including melasma and found that QSRL provided a slightly better treatment response than the QS Nd:YAG laser.[33] Most patients found QSRL to be more painful during treatment but QS Nd:YAG laser caused more post-operative discomfort. However, the results of Taylor et al. were contrary. They treated eight patients with melasma and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation with QSRL pulses (694 nm, 40 ns) at fluences 1.5–7.5 J/cm2 and found it to be ineffective for melasma and PIH.[34] Jang et al. treated 15 Korean patients with dermal/mixed melasma with six sessions of low-dose fractional QSRL (694 nm) treatment at 2-week intervals.[35] Fluence used was 2–3 J/cm2 and pulse duration was 40 ns. There was 30% improvement in melasma. Neither hypopigmentation nor hyperpigmentation was observed in any patient after treatment. The difference in this study was the lower doses used compared to previous studies and fractional mode used. The low-dose fractional mode exposes the skin to lower total cumulative energy. Hence, the side effects were less.

The role of Ruby laser is controversial with studies showing conflicting results. More studies are needed to establish its efficacy and safety in melasma.

ERBIUM:YAG LASER

The erbium:YAG (Erbium:Yttrium-Aluminium-Garnet) laser emits light with a 2940-nm wavelength which is highly absorbed by water. Hence, it ablates the skin with minimal thermal damage. The risk of PIH is reduced. There are very few studies on the use of erbium:YAG for melasma.

Manaloto et al. treated 10 female patients with refractory melasma using erbium:YAG laser at energy levels of 5.1–7.6 J/cm.[36] There was marked improvement of melasma immediately after treatment. However, between 3 and 6 weeks post-operatively, all patients developed PIH that responded well to biweekly glycolic acid peels and topical azelaic acid and sunscreens. The PIH could be due to the inflammatory dermal reaction induced by laser that stimulated the activity of melanocytes in treated skin.

The occurrence of PIH limits the use of this laser for recalcitrant melasma. Moreover, there are hardly any studies documenting its efficacy in melasma.

PULSED DYE LASER

The use of pulsed dye laser (PDL) for the treatment of melasma is based on the theory that skin vascularization plays an important role in the pathogenesis of melasma. Melanocytes express vascular endothelial growth factor receptors 1 and 2 which are involved in the pigmentation process.[37] PDL, which is mainly used for vascular lesions, targets the vascular component in melasma lesions, decreasing the melanocyte stimulation and subsequent relapses.

A study was conducted in 17 patients with melasma who were treated with PDL and TCC.[38] The combination treatment was compared with TCC alone. The laser treatment was started after 1 month of TCC applications. Three sessions were performed at 3 weekly intervals at the following settings: fluence 7–10 J/cm2, pulse duration 1.5 ms. The authors found that the combination treatment had greater treatment satisfaction in patients with skin phototypes II and III. PIH was seen in three patients which could be due to pass used for targeting melanin.

FRACTIONAL LASERS

Fractional phtothermolysis is a new concept in laser therapy in which multiple microscopic zones of thermal damage are created leaving the majority of the skin intact. The latter serves as a reservoir for healing. These multiple columns of thermal damage are called microthermal treatment zones (MTZ) and lead to extrusion of microscopic epidermal necrotic debris (MENDs) that includes pigment in the basal layer. The viable keratinocytes at the wound margins facilitate the migration of MENDs. The depth and diameter of MTZ are determined by the energy levels used. 6 mJ/MTZ corresponds to a diameter of 80 μm and depth of 360 μm in each MTZ.[6] The density used and the number of passes determine the proportion of surface area treated.

There are numerous advantages of fractional laser therapy. The technique does not create an open wound. The stratum corneum is found to be intact after 24 h of treatment. Hence, the recovery is faster and complications of open wounds such as hyper or hypopigmentation are avoided. There is less risk of scarring so areas such as neck and chest that are more prone to scarring can be safely treated. Also, greater depths of penetration can be achieved as entire skin surface is not ablated. Hence, dermal melasma can be targeted.

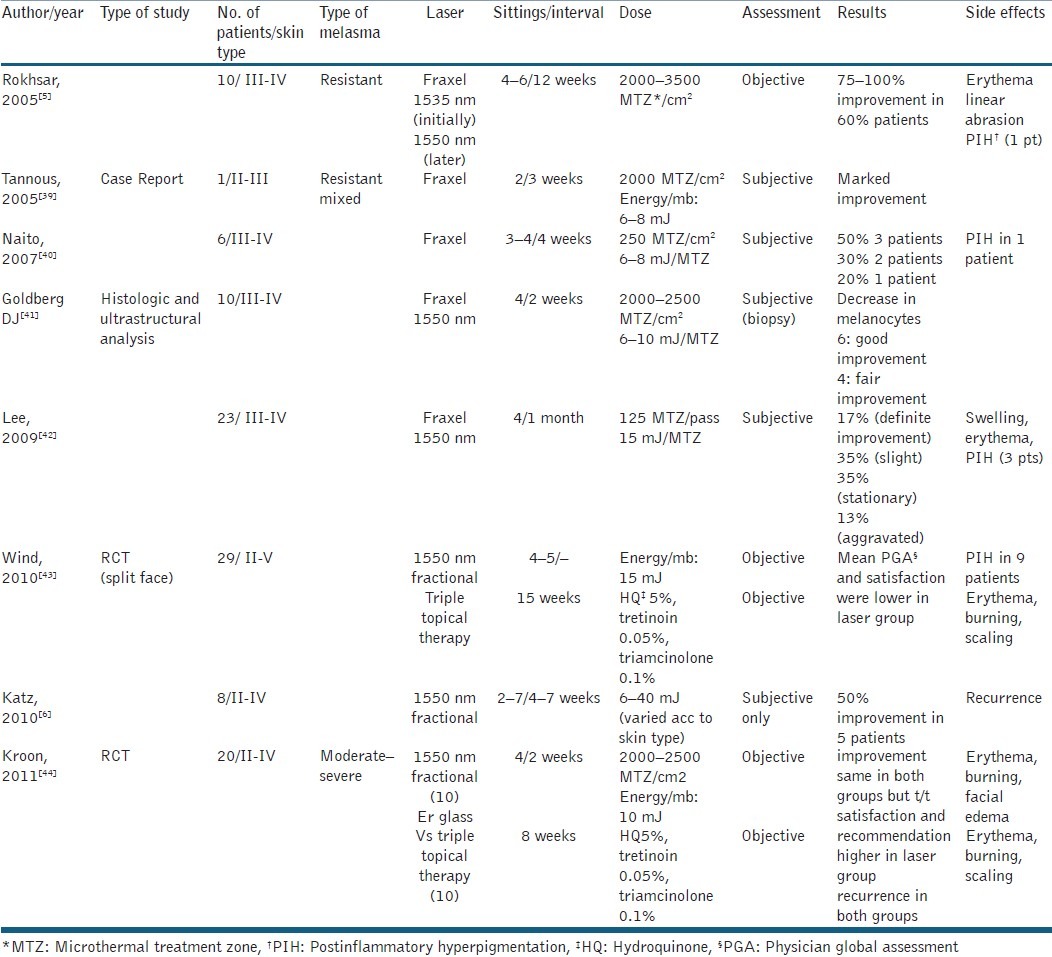

There are eight reported studies[5,6,39–44] of patients with melasma who were treated with fractional laser 1550 nm. These are summarized in Table 2. Out of these, two are randomized controlled trials.[43,44] One of these is by Kroon et al.[44] who assessed the efficacy and safety of non-ablative fractional laser therapy and compared the results with those obtained with gold standard therapy, that is, the triple topical therapy (TTT). They treated 20 female patients with moderate to severe melasma with either non-ablative fractional laser (performed every 2 weeks for a total of four sessions) or TTT (once daily for 8 weeks). They used a density of 2000–2500 MTZ/cm2 with energy per microbeam of 10 mJ. Improvement was same in both the groups, but treatment satisfaction and recommendation was higher in laser group. Also, recurrence was noted in both the groups. No case of PIH was seen.

Table 2.

Various studies using fractional laser (1550 nm) for melasma

The above findings are different from those obtained by Wind et al.[43] who performed a randomized, controlled split face study in 29 patients with melasma. One side of the face was treated with four to five non-ablative fractional laser therapy sessions (15 mJ/microbeam, 2000–2500 MTZ/cm2) and the other side with TTT applied once daily for 15 weeks. Mean PGA and satisfaction were significantly lower for the side treated with laser. At 6 months follow-up, most patients preferred TTT. Also, 31% patients in the laser group developed PIH. This incidence is relatively higher than that seen in other studies. This could be due to the relatively higher energy per microbeam (15 mJ) used in this study compared to other studies (10 mJ). Although few authors believe that the occurrence of PIH is independent of the energy levels used and depends on the density of MTZ, but few studies have shown that it does play a role.[45] Another reason for the PIH could be seasonal as treatment was performed in spring. Also, Lee et al.[42] found PIH in only 13% of patients with similar settings. Nevertheless, this energy level (15 mJ/mb) is not recommended for treatment of melasma.

Goldberg DJ and colleagues[41] analyzed the histological and ultrastructural characteristics of melasma after fractional resurfacing in 10 patients after four treatment sessions and 3 months follow-up biopsy showed a reduced number of melanocytes which implies that non-ablative fractional laser delayed pigmentation. However, at 6 months follow-up recurrence was noted in 50% patients suggesting that repigmentation could not be delayed for a prolonged period.

Various other studies done with fractional laser are summarized in Table 2. The density used varies from 2000 to 2500 MTZ/cm2 and energy levels 10 to 15 mJ/ mb. The treatment sessions vary from 2 to 6 at an interval of 1–4 weeks. Levels of improvement vary in different studies.

It can be inferred that topical bleaching agents should be regarded as the gold standard in the therapy of melasma.[46,47] The treatment is cheap and less painful. Non-ablative fractional laser (1550 nm) is safe and comparable in efficacy and recurrence rate with TTT and should be used only when the latter is ineffective or not tolerated.

Recently, Polder et al. treated 14 patients of melasma with a novel 1927-nm fractional thulium fibre laser.[48] This wavelength has a higher absorption coefficient for water than the 1550 nm laser, hence targets the epidermal pigment with greater efficacy. They used three to four laser treatments at 4-week intervals at pulse energies of 10–20 mJ and total densities of 252–784 MTZ/cm2. A statistically significant 51% improvement in melasma was seen without any PIH. The efficacy and safety of this laser needs to be further evaluated with future studies.

Figures 1 and 2 depict a patient with melasma treated at our centre with Fraxel laser (1550nm) at energy levels of 10-40mJ and treatment level 4. Five sessions were performed and patient showed good improvement. However, there was relapse on follow up.

Figure 1.

(a) Patient with melasma before treatment (left oblique view). (b) Patient after five treatments with the Fraxel Laser (1550 nm) at 10–40 mJ (treatment level 4)

Figure 2.

(a) Right oblique view of same patient. (b) Patient after five treatments with the Fraxel Laser (1550 nm) at 10–40 mJ (treatment level 4)

Intense pulse light

IPL was developed in the late 1990s and involves the use of a xenon-chloride lamp that emits light that is non-coherent not collimated and has a wide spectrum (500–1200 nm). The advantage of IPL lies in the flexibility of parameters. The wavelength, fluence, number, duration, and delay of pulses can be changed for each patient to effectively target chromophore. Hence, it can be used for the treatment of a variety of conditions like vascular lesions, hair removal, and melanocytic lesions. However, there are very few studies on the treatment of melasma with IPL.

According to Kawada et al., the mechanism of effectiveness of IPL involves absorption of light energy by melanin in keratinocytes and melanocytes leading to epidermal coagulation due to photothermolysis followed by microcrust formation.[49] These crusts containing melanin are shed off hence, the clinical improvement in pigmentation.

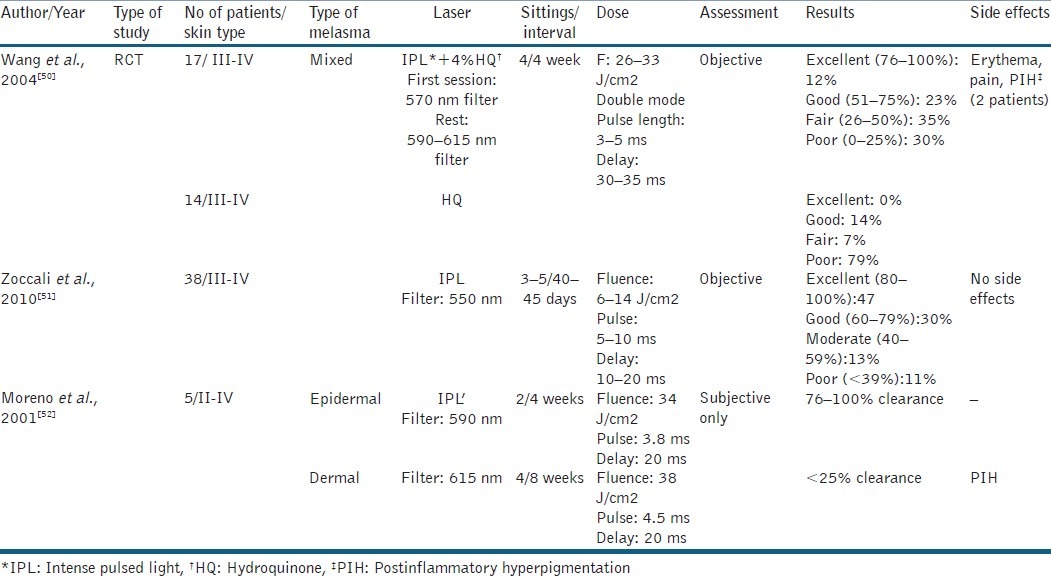

Various studies done with IPL for the treatment of melasma are summarized in Table 3.[50–52] Zoccali et al. treated 38 patients with melasma using cutoff filters of 550 nm, pulse of 5–10 ms, pulse delay of 10–20 ms, and low fluence 6–14 J/cm2 and found 80–100% clearance in 47% of patients.[51] The number of sessions used was 3–5 at interval of 40–45 days. No side effects were seen. Moreno Arias and Fernando, in their study of IPL and melanocytic lesions, treated two patients with epidermal melasma and achieved 76–100% clearance with fluence of 34 J/cm2, pulse width of 3.8 ms, double mode, and pulse delay of 20 ms.[52] However, three patients with mixed melasma showed less than 25% clearance with 615 nm filter, fluence 38 J/cm2, pulse width of 4.5 ms, double mode, and delay of 20 ms. Patients developed PIH.

Table 3.

Various studies of patients with melasma treated with IPL

The only RCT done in this domain is that by Wang et al. in which patients with refractory melasma were treated with IPL and hydroquinone and compared with hydroquinone alone.[50] 570 nm cutoff filter was used in the first session and 590–615 nm filters for subsequent sessions to target deeper melanin. Fluence used varied from 26 to 33 J/cm2, double mode and pulse length of 3–4 and 4–5 ms, respectively. However, in this study the authors preferred to use long delay between pulses (30–35 ms) which is higher compared to other studies. The IPL group achieved a significant response (39.8% clearance) compared to control group (11.6% clearance). Treatment efficacy did not correlate with any variables, such as age, duration of melasma, or skin phototype. Also, there was recurrence 6 months after therapy indicating the need for additional treatments to maintain results.

The laser settings play an important role in the treatment. 500–550 nm filters can be used initially and for epidermal lesions, whereas higher wavelength filters can be used to target deeper melanin hence patients with dermal/mixed melasma. The fluence can be modulated in relation to the anatomic sites. Higher fluence can be used for cheek and zygoma, whereas perioral region and neck need lower fluencies. Higher fluencies are useful for deeper lesions but cause PIH in dark skinned patients. Therefore, for darker skin, lower fluence should be used. Single pulses heat pigment well, but double or triple pulses should be used as they reduce the thermal damage by allowing the epidermis to cool while the target stays warm. The pulse duration used in the studies varied from 3 to 5 ms. Average pulse delay used was 10–20 ms. However, Wang et al. used long delay between pulses (30–35 ms) with good results.[50] It is important that delay time between pulses should not be below 10 ms as this increases the risk of thermal damage as the targeted tissue cannot reduce its temperature within that time. Average number of sessions used in these studies was 2–5 at an interval of 4–8 weeks. However, more number of sessions is required for maintenance and it decreases the chances of recurrence.

It is a good approach to do a pre-test session before starting treatment to assess the efficacy of settings and look for any cutaneous hyper-reactivity.

The studies show that IPL is effective for epidermal melasma. Dermal or mixed or refractory melasma can be targeted with higher fluencies though the risk of PIH should be kept in mind in darker skin. It is a good approach to use low fluences and long delay between pulses in such cases as done by Wang et al.[50] Also, sun protection and hydroquinone should be used throughout treatment and thereafter.

Patients treated in these studies also had additional benefits of brighter skin colour, smoother skin texture, and uniform pigmentation.[50]

Zoccali and colleagues used dermoscopy to assess the area immediately after treatment session to choose the correct parameters: a transient hyperpigmentation (colour change to grey) indicating a correct IPL setting.[51] Post-dermoscopy is helpful in evaluating the IPL efficacy and healing process. Post IPL dermoscopic finding can be classified into three patterns: (1) spotty/small dotted, (2) reticulated, and (3) complex (clumped). These clinical patterns represent clinical pictures of microcrust formed during the process.[49]

COMBINATION OF LASERS

Combination of ablative and pigment selective lasers has been tried in melasma. Refractory melasma contains abnormal pigment in both epidermis and dermis. Ablative lasers remove the epidermis (containing excess melanin and abnormal melanocytes). This can be followed by use of Q switched pigment selective laser that reach deeper lesion in dermis (dermal melanophages) without causing serious side effects.

Angsuwarangsee et al. carried out study in six patients with refractory melasma and compared combined ultrapulse CO2 laser and QS alexandrite laser (QSAL) alone. The site that received combination treatment showed significant response compared to the site that was treated with QSAL alone.[53] However, contact dermatitis and hyperpigmentation were observed in few patients. The latter was seen in dark skinned patients. Hence, the approach should only be used for refractory melasma.

PIH AND LASER

PIH is an acquired pigmentary disorder of skin that occurs as a result of inflammation induced by various cutaneous diseases and therapy. Various conditions that are associated with PIH include acne, folliculitis, lichen planus, herpes zoster, and eczema. It can occur as sequelae to trauma, medications, and as a complication of laser therapy.

All these conditions cause damage to the basal cell layer leading to accumulation of melanophages in upper dermis that remain there for sometime. Also, archidonic acid, prostaglandins, and leucotrienes released as a result of inflammation stimulate the epidermal melanocytes leading to increase in melanin synthesis.[54] Histopathology reveals increased epidermal melanin with melanophages in superficial dermis. Lymphohistiocytic infiltrate is seen around superficial blood vessels in the dermal papillae.

PIH occurs with equal incidence in males and females but is more common in darker skin types. The distribution of causative dermatoses determines the site of PIH. The lesions vary in colour from light-brown to bluish-grey and are irregularly shaped. PIH generally persists for months to years.

The treatment of PIH still remains a challenge. The underlying disorder causing the hyperpigmentation should be treated. Patients should be advised daily use of sunscreens. Many topical medications have been used for PIH. These include hydroquinone, TCCs, kojic acid, retinoids, corticosteroids, and vitamin C. Chemical peeling and dermabrasion have been tried with variable success.[55] Combination therapies have shown good results.

Recently, several lasers have been tried for the treatment of PIH. QSRL has been used in PIH with unsatisfactory results. Taylor et al.[34] treated eight patients with melasma or PIH with Q S ruby laser pulses (694 nm, 40 ns) at fluences of 15–7.5 J/cm2 and did not find any improvement, whereas Tafazzoli and colleagues[56] observed 75–100% of improvement in 58% of patients of post-sclerotherapy hyperpigmentation treated with QS ruby laser. Cho and colleagues treated three patients with PIH with QS Nd:YAG 1064 nm laser at fluences of 1.9–2.6 J/cm2 and five sessions and good results.[57] The therapy required minimal downtime without post-therapy bleeding or crust formation. 1064 nm, being a longer wavelength, penetrates deeper causing less risk of PIH with the treatment itself. However, the efficacy and safety of this laser still remain unknown and require future studies.

The concept of fractional photothermolysis has been used for PIH as well. Katz et al. treated one patient with post-traumatic hyperpigmentation with 1550 nm erbium doped Fraxel laser using density of 880–1100 MTZ/cm2.[9] The patient achieved >95% clearance with three treatment sessions. Similarly, Rukhsar et al. treated a female patient with CO2 laser resurfacing induced PIH with 1550 Fraxel laser.[10] They used higher densities of 2000–3000 MTZ/cm2 and found 50–75% improvement after five sessions over a 2-month period. No side effects were seen.

PIH can occur as a complication of fractional photothermolysis itself although it is more common after ablative laser therapy. The incidence quoted in one study was 0.73% for patients treated with fractional photothermolysis.[58] Lowering the treatment densities and using cooling devices along with laser can reduce the risk of PIH after FP.[59]

Kono and colleagues conducted a prospective direct comparison study of fractional resurfacing using different fluences and densities for skin rejuvenation and found that greater density was more likely to produce erythema, swelling, and hyperpigmentation.[60]

More controlled studies with larger sample size and patients with darker skin types are needed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of lasers for PIH.

CONCLUSION

Lasers have revolutionized the treatment of dermatological disorders but its place in the management of melasma and PIH is still controversial. Various studies documented in this review focus on the importance of laser settings to derive maximum efficacy and minimal side effects. Choosing the appropriate laser and the correct settings is vital in the treatment of melasma. Also, topical bleaching agents remain the gold standard of therapy as they are evidence-based, are cheap, and of equal or greater efficacy compared to lasers. So the use of latter should be restricted to cases unresponsive to topical therapy or combination with chemical peels. Appropriate maintenance therapy should be selected to avoid relapse of melasma.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson RR, Parrish JA. Selective photothermolysis. Precise microsurgery by selective absorption of pulsed radiation. Science. 1983;220:524–7. doi: 10.1126/science.6836297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stratigos AJ, Dover JS, Arndt KA. Laser treatment of pigmented lesions – 2000. How far have we gone? Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:915–21. doi: 10.1001/archderm.136.7.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldberg DJ. Laser treatment of pigmented lesions. Dermatol Clin. 1997;15:397–406. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8635(05)70449-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manstein D, Herron GS, Sink RK, Tanner H, Anderson RR. Fractional photothermolysis: A new concept of cutaneous remodeling using microscopic patterns of thermal injury. Lasers Surg Med. 2004;34:426–38. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rokhsar CK, Fitzpatrick RE. The treatment of melasma with fractional photothermolysis: A pilot study. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:1645–50. doi: 10.2310/6350.2005.31302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katz TM, Glaich AS, Goldberg LH, Firoz BF, Dai T, Friedman PM. Treatment of melasma using fractional photothermolysis: A report of eight cases with long-term follow-up. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1273–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2010.01621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glaich AS, Goldberg LH, Dai T, Kunishige JH, Friedman PM. Fractional resurfacing: A new therapeutic modality for Becker's nevus. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1488–90. doi: 10.1001/archderm.143.12.1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kouba DJ, Fincher EF, Moy RL. Nevus of Ota successfully treated by fractional photothermolysis using a fractionated 1440-nm Nd:YAG laser. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:156–8. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2007.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katz TM, Goldberg LH, Firoz BF, Friedman PM. Fractional photothermolysis in the treatment of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1844–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rokhsar CK, Ciocon DH. Fractional photothermolysis for the treatment of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation after carbon dioxide laser resurfacing. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:535–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katsambas A, Antoniou Ch. Melasma. Classification and treatment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1995;4:217–23. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Resnik S. Melasma induced by oral contraceptive drugs. JAMA. 1967;199:601–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carruthers R. Chloasma and the oral contraceptives. Med J Aust. 1966;2:17–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kang WH, Yoon KH, Lee ES, Kim J, Lee KB, Yim H, et al. Melasma: Histopathological characteristics in 56 Korean patients. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:228–37. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-0963.2001.04556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee MW. Combination 532-nm and 1064-nm lasers for noninvasive skin rejuvenation and toning. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:1265–76. doi: 10.1001/archderm.139.10.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim EH, Kim YC, Lee ES, Kang HY. The vascular characteristics of melasma. J Dermatol Sci. 2007;46:111–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmults CD, Phelps R, Goldberg DJ. Nonablative facial remodeling, erythema reduction and histologic evidence of new collagen formation using a 300-microsecond 1064-nm Nd:YAG laser. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1373–6. doi: 10.1001/archderm.140.11.1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wattanakrai P, Mornchan R, Eimpunth S. Low-fluence Qswitched neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet (1,064 nm) laser for the treatment of facial melasma in Asians. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:76–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Polnikorn N. Treatment of refractory melasma with the MedLite C6 Q-switched Nd:YAG laser and alpha arbutin: A prospective study. Cosmet Laser Ther. 2010;12:126–31. doi: 10.3109/14764172.2010.487910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choi M, Choi JW, Lee SY, Choi SY, Park HJ, Park KC, et al. Low-dose 1,064-nm Qswitched Nd:YAG laser for the treatment of melasma. J Dermatol Treat. 2010;21:224–8. doi: 10.3109/09546630903401462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jeong SY, Shin JB, Yeo UC, Kim WS, Kim IH. Low-fluence Qswitched neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet laser for melasma with pre- or post-treatment triple combination cream. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2010.01523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chan NP, Ho SG, Shek SY, Yeung CK, Chan HH. A case series of facial depigmentation associated with low fluence Q-switched 1,064 nm Nd:YAG laser for skin rejuvenation and melasma. Lasers Surg Med. 2010;42:712–9. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park KY, Kim DH, Kim HK, Li K, Seo SJ, Hong CK. A randomized, observer-blinded comparison of combined 1064 nm Q-switched neodymium-doped yttrium aluminium laser plus glycolic acid peel vs. laser monotherapy to treat melasma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011:864–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2011.04150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou X, Gold MH, Lu Z, Li Y. Efficacy and safety of Q-switched1064 neodymium-doped yttrium aluminium laser treatment of melasma. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:962–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.02001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suh KS, Sung JY, Roh HJ, Jeon YS, Kim YC, Kim ST. Efficacy of the 1064-nm Q-switched Nd:YAG laser for melasma. J Dermatolog Treat. 2011;22:233–8. doi: 10.3109/09546631003686051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Polnikorn N. Treatment of refractory dermal melasma with the MedLite C6 Q-switched Nd:YAG laser: Two case reports. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2008;10:167–73. doi: 10.1080/14764170802179687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown AS, Hussain M, Goldberg DJ. Treatment of melasma with low fluence, large spot size, 1064-nm Q-switched neodymium-doped yttrium aluminium garnet) Nd:YAG laser for the treatment of melasma in Fitzpatrick skin types II-IV. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2011;13:280–2. doi: 10.3109/14764172.2011.630084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berlin AL, Dudelzak J, Hussain M, Phelps R, Goldberg DJ. Evaluation of clinical, microscopic, and ultrastructural changes after treatment with a novel Q-switched Nd:YAG laser. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2008;10:76–9. doi: 10.1080/14764170802071165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim MJ, Kim JS, Cho SB. Punctate leucoderma after melasma treatment using 1064-nm Q-switched Nd:YAG laser with low pulse energy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:960–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2008.03070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anderson RR, Margolis RJ, Watenabe S, Flotte T, Hruza GJ, Dover JS. Selective photothermolysis of cutaneous pigmentation by Q-switched Nd:YAG laser pulses at 1064, 532, and 355 nm. J Invest Dermatol. 1989;93:28–32. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12277339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chan HH, Yang CH, Leung JCK. An animal study of the effects on p16 and PCNA expression of repeated treatment with high energy laser and intense pulsed light exposure. Lasers Surg Med. 2007;39:8–13. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chan HH, Xiang L, Leung JC, Tsang KW, Lai KN. An in vitro study examining the effect of sub- lethal QS 755 nm lasers on the expression of p16INK4a on melanoma cell lines. Lasers Surg Med. 2003;32:88–93. doi: 10.1002/lsm.10118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tse Y, Levine VJ, Mcclain SA, Ashinoff R. The removal of cutaneous pigmented lesions with the Q-switched ruby laser and the Qswitched neodymium:yttrium-aluminum-garnet laser: A comparative study. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1994;20:795–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1994.tb03707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taylor CR, Anderson RR. Ineffective treatment of refractory melasma and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation by Q-switched ruby laser. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1994;20:592–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1994.tb00152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jang WS, Lee CK, Kim BJ, Kim MN. Efficacy of 694-nm Q-switched ruby fractional laser treatment of melasma in female Korean patients. Dermatol Surg. 2011;37:1133–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.02018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manaloto RMP, Alster TS. Erbium:YAG laser resurfacing for refractory melasma. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:121–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.1999.08103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Plonka PM, Passeron T, Brenner M, Tobin DJ, Shibahara S, Thomas A, et al. What are melanocytes really doing all day long…? Exp Dermatol. 2009;18:799–819. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2009.00912.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Passeron T, Fontas E, Kang HY, Bahadoran P, Lacour JP, Ortonne JP. Melasma treatment with pulsed-dye laser and triple combination cream: A prospective, randomized, single-blind, split-face study. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1106–8. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2011.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tannous ZS, Astner S. Utilizing fractional resurfacing in the treatment of therapy-resistant melasma. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2005;7:39–43. doi: 10.1080/14764170510037752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Naito SK. Fractional photothermolysis treatment for resistant melasma in Chinese females. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2007;9:161–3. doi: 10.1080/14764170701418814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goldberg DJ, Berlin AL, Phelps R. Histologic and ultrastructural analysis of melasma after fractional resurfacing. Lasers Surg Med. 2008;40:134–8. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee HS, Won CH, Lee DH, An JS, Chang HW, Lee JH, et al. Treatment of melasma in Asian skin using a fractional 1,550-nm laser: An open clinical study. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:1499–1504. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2009.01264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wind BS, Kroon MW, Meesters AA, Beek JF, van der Veen JP, Nieuweboer-Krobotová L, et al. Nonablative 1550-nm fractional laser therapy versus triple topical therapy for the treatment of melasma. Lasers Surg Med. 2010;42:607–12. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kroon MW, Wind BS, Beek JF, van der Veen JP, Nieuweboer-Krobotová L, Bos JD, et al. Nonablative 1550-nm fractional laser therapy versus triple topical therapy for the treatment of melasma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:516–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Graber EM, Tanzi EL, Alster TS. Side effects and complications of fractional laser photothermolysis: Experience with 961 treatments. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:301–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.34062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Picardo M, Carrera M. New and experimental treatments of cloasma and other hypermelanoses. Dermatol Clin. 2007;25:353–62. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2007.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pandya A, Berneburg M, Ortonne JP, Picardo M. Guidelines for clinical trials in melasma: Pigmentation Disorders Academy. Br J Dermatol. 2006;156(Suppl):S21–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Polder KD, Bruce S. Treatment of melasma using a novel 1,927 nm fractional thulium fiber laser: A pilot study. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:199–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.02178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kawada A, Asai M, Kameyama H, Sangen Y, Aragane Y, Tezuka T, et al. Videomicroscopic and histopathological investigation of intense pulsed light for solar lentigines. J Dermatol Sci. 2002;29:91–6. doi: 10.1016/s0923-1811(02)00014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang CC, Hui CY, Sue YM, Wong WR, Hong HS. Intense pulse light for the treatment of refractory melasma in Asian patients. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:1196–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2004.30371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zoccali G, Piccolo D, Allegra P, Giuliani M. Melasma treated with intense pulsed light. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2010;34:486–93. doi: 10.1007/s00266-010-9485-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moreno Arias GA, Ferrando J. Intense pulsed light for melanocytic lesions. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:397–400. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2001.00315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Angsuwarangsee S, Polnikorn N. Combined ultrapulse CO2 laser and Q-switched alexandrite laser compared with Q-switched alexandrite laser alone for refractory melasma: Split face design. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:59–64. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2003.29009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tomita Y, Maeda K, Tagami H. Mechanisms for hyperpigmentation in postinflammatory pigmentation, urticaria pigmentosa and sunburn. Dermatologica. 1989;179(Suppl 1):49–53. doi: 10.1159/000248449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Burns RL, Prevost-Blank PL, Lawry MA, Lawry TB, Faria DT, Fivenson DP. Glycolic acid peels for postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in black patients.A comparative study. Dermatol Surg. 1997;23:171–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1997.tb00014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tafazzoli A, Rostan EF, Goldman MP. Q-Switched ruby laser treatment for postsclerotherapy hyperpigmentation. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:653–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2000.99268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cho SB, Park SJ, Kim JS, Kim MJ, Bu TS. Treatment of post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation using 1064-nm Q-switched Nd:YAG laser with low fluence: report of three cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:1026–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Graber EM, Tanzi EL, Alster TS. Side effects and complications of fractional laser photothermolysis: Experience with 961 treatments. Dermatol Surg. 2008;34:301–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.34062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chan HH, Manstein D, Yu CS, Shek S, Kono T, Wei WI. The prevalence and risk factors of post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation after fractional resurfacing in Asians. Lasers Surg Med. 2007;38:381–5. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kono T, Chan HH, Groff WF, Manstein D, Sakurai H, Takeuchi M, et al. Prospective direct comparison study of fractional resurfacing using different fluences and densities for skin rejuvenation in Asians. Lasers Surg Med. 2007;39:311–4. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]