Abstract

The pivotal role of T cells in the etiology of psoriasis has been elucidated; however, the mechanisms that regulate these T cells are unclear. Recently, it has been shown that an IL-10 producing B cell population may downregulate T cell function and it has been hypothesized that depletion of this B cell population may lead to exacerbation of T-cell mediated autoimmune disease. We present the case of an adolescent male with autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome (ALPS) being treated with the anti-CD20 chimeric monoclonal antibody rituximab in addition to intravenous immune globulin (IVIG) for immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) who developed a psoriasiform rash on his hands following mechanical trauma with concomitant severely decreased B cell count. We propose that depletion of the patient's B cells due to rituximab treatment may have led to abrogation of IL-10+ B-cell regulation of T cells. The development of a psoriasiform rash in this predisposed individual may have been triggered by mechanical trauma to his hands (koebnerization). In addition, we believe the patient's rash may have been tempered by concomitant treatment with IVIG, which has been used as treatment in cases of psoriasis. We discuss the immunologic mechanism of psoriasis and the role that a recently described IL-10+ B cell may play in preventing the pathologic process. Further studies are needed to more clearly elucidate this process.

INDEX TERMS: ALPS, IL-10, IVIG, psoriasiform, rituximab

INTRODUCTION

Psoriasis is currently thought to be a T-cell mediated disease in which T cells and innate immune cells are activated to cause inflammation and keratinocyte hyperproliferation. The trigger that initiates the inflammatory reaction in psoriasis remains elusive and current opinion holds that an imbalance of pro- and anti-inflammatory factors favors the activation of dendritic cells and T cells in psoriatic plaques. Increased production of inflammatory cytokines, like IFN-g, TNF-a, IL-6, IL-12, IL-17 and IL-23 has been demonstrated in lesional skin and the role of Th-1, Th-17, regulatory T cells and dendritic cells is subject to intensive research.2 However, the role of B cell involvement in psoriasis has not been clearly delineated. Recently, it has been shown that IL-10+ B cells suppress T-cell mediated cutaneous hypersensitivity to oxazolone in a mouse model and it has been hypothesized that this B cell subtype may possess the ability to regulate T cells after Toll-like receptor ligation.3 Additionally, reports from lupus and rheumatoid arthritis patients that were treated with B-cell depleting strategies and subsequently developed psoriasis support this idea.4

Rituximab is a therapeutic anti-CD20 chimeric monoclonal antibody used in the treatment of neoplastic diseases, particularly non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and B-cell leukemias. In addition, it has also found use in treatment for autoimmune diseases including systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis,5 idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura,6 autoimmune bullous diseases, and immune-thrombocytopenia in patients with underlying autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome (ALPS).7 After ligation of CD20, rituximab induces apoptosis, complement activation, and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) that as a consequence leads to depletion of B cells.8

We report the case of an adolescent with underlying ALPS who received rituximab and intravenous immune globulin (IVIG) for treatment of immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) and subsequently developed hand and nail psoriasis after trauma to his hand. We discuss the possibility that depletion of regulatory B cells may have resulted in unrestrained activation of T cells and development of psoriasis. IVIG has been reported to be a treatment option for recalcitrant psoriasis9,10 and co-administration of IVIG in our patient may have ameliorated the severity of psoriasis and could have resulted in confinement of the disease to the hands, an area that was traumatized (koebnerized) prior to the onset of the rash.

CASE

The patient is a 17-year-old Caucasian male with a history of common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) with hypogammaglobulinemia (baseline IgG 504 mg/dL) and an additional diagnosis of ITP as a consequence of autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome type III (ALPS). He was referred to the dermatology clinic by his pediatric hematology/oncology physician for a three to four week history of a worsening rash on both hands. Ten months ago, he was diagnosed with CVID/ALPS type III with ITP. At that time, the patient's platelet count decreased to less than 10 × 109 cells/L and he was treated with systemic steroids. The steroids were weaned and he received rituximab (668 mg IV) weekly for 4 weeks (standard dose is 375 mg/m2 weekly for 4 weeks), and has since been managed with monthly low dose IVIG (25 g IV) for the past 7 months (no standard dosing for this patient's condition; dosing was based on patient's response). Since initiating treatment, his platelet count has remained greater than 10 × 109 cells/L.

At presentation, the patient reported that he hit his left fourth digit with a hammer approximately 4 weeks ago. Soon after, he developed a persistent “tight” sensation at the site without obvious skin changes. Over the next few weeks pruritic, erythematous plaques appeared on his fingertips (left hand predominantly involved) spreading proximally to the palmar and dorsal aspect of the fingers, then to the palms and dorsal aspect of the hands. The morphology did not significantly change over time, though the patient reported increasing discomfort over the involved areas. He did not notice any skin changes elsewhere on his body and denied joint pain. The patient did not recently use any new creams or lotions and did not have any hand contact with new or foreign materials. In addition, there is no personal history of skin problems and no family history of psoriasis.

On physical examination the left hand was found to have erythematous plaques involving the distal part of the digits. Well-defined hyperkeratotic red plaques were noticeable on the dorsal third digit and the webspace between the thumb and the second digit. Similar findings were also found on the right thumb and third digit. Fingernail examination revealed onychodystrophy, distal onycholysis and pitting of most nails. The remainder of the physical examination was normal.

A complete blood count at the time of presentation revealed the following values: WBC 6.7 × 109 cells/L; PMN's 55%; Lymphocytes 19%; Monocytes 17%; Eosinophils 7%; Basophils 1%; Hemoglobin 14.7 g/dL; Hematocrit 43.0%; Platelets 486 × 109 cells/L. Further studies revealed T cells to be within normal range. However, the B cell count was noted to be extremely low, with a CD19 level < 0.1%. In addition, B cell activating factor was found to be elevated at 14,660 pg/ mL (normal range, 551–1775 pg/mL). Immunology studies one month prior to onset of the rash showed normal levels of IgG (689 mg/dL) and IgE (6 mg/dL) and decreased IgA (13 mg/dL) and IgM (17 mg/dL).

After physical examination, the patient was diagnosed with psoriasis and started on clobetasol ointment twice daily for 2 weeks, then weaned to triamcinolone ointment applied to affected areas. At a follow-up appointment 4 weeks later, the psoriasiform rash had essentially cleared, and the patient was without complaints. Since then, the patient has not had any recurrences or any new dermatologic complaints. He continues to receive IVIG treatments and his B cell counts have not yet recovered ten months after being treated with rituximab.

DISCUSSION

Psoriasis is believed to be an autoimmune mediated disease where T cells, dendritic cells, keratinocytes and neutrophils are activated by an unknown trigger, resulting in inflammation as well as vascular and epithelial proliferation leading to formation of psoriasis plaques. It is speculated that activation of dermal dendritic cells by a yet-to-be-identified event and subsequent cytokine secretion and induction of co-stimulatory molecules sparks activation of Th1 and Th17 cells in the dermis which orchestrate the recruitment of other inflammatory cells and activate keratinocytes and blood vessels. Dysfunctional regulatory T cells fail to inhibit the activity of conventional T cells in the skin.2 The Koebner phenomenon (isomorphic effect) is a well known phenomenon in psoriasis and refers to the appearance of skin lesions following physical skin trauma. It can be hypothesized that trauma localized to an area of skin activates dendritic cells, keratinocytes, and blood vessels locally and initiates the psoriatic cascade that leads to T cell activation.

It is often seen that individuals with an autoimmune disease have a tendency to develop other dermatologic autoimmune phenomena. Such examples include vitiligo with thyroiditis, pyoderma gangrenosum with inflammatory bowel disease, and dermatitis herpetiformis with celiac disease. Interestingly, despite the relatively high incidence of psoriasis in the general population, no other autoimmune disease has been linked.

ITP and ALPS have been closely associated. ALPS is an inherited disorder whereby patients will have unusually large numbers of circulating lymphocytes due to faulty apoptotic signaling, most often as a result of Fas gene mutation. Though not considered a malignancy, the disease nonetheless may result in accumulation of lymphocytes in lymph nodes, the spleen, and liver. Symptoms may occur if the uninhibited proliferation of lymphocytes leads to B cell production of auto-antibodies, including the anti-platelet antibodies that are pathognomic for ALPS-associated ITP. Other associated autoimmune phenomenon can include hemolytic anemia and autoimmune neutropenia. There have been no reports conclusively linking ALPS with the development of psoriasis. First line treatment for ALPS and associated ITP are steroids. However, refractory cases have been managed with IVIG and rituximab.

The precise mechanism of action of IVIG with regards to autoimmune disease treatment is unclear. It has been postulated that IVIG interacts with the inhibitory Fc receptor to stimulate anti-inflammatory activity.11 Rituximab is a chimeric anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody that binds to the CD20 receptor on B cells and its functions have been found to include induction of apoptosis and down-regulation of B-cell receptors, with a net result of decreased B cell count and function.12 Thus, rituximab has been an effective treatment in antibody-mediated autoimmune diseases in addition to its more conventional use in B-cell dominant neoplastic diseases such as non-Hodgkin's lymphoma.

The patient in this case was treated with rituximab and found to have a CD19 level of less than 0.1% at the onset of the psoriasiform rash, indicating a B cell deficiency secondary to rituximab treatment. A subset of IL-10 producing B cells has been found to have anti-inflammatory activity by diminishing both acquired and innate immune response. These IL-10+ B cells inhibit the pro-inflammatory and chemotactic promoters for CD4+ and CD8+ T cell proliferation.13 With our patient's depleted B cell count the ability of these IL-10+ B cells to inhibit T cell activity was likely markedly diminished, possibly leading to unmitigated proliferation of Th1 and Th17 within the dermis and the resultant declaration of the psoriasiform rash after Koebnerization. The patient reports hitting his finger with a hammer several days prior to the onset of the rash on his fingers. Koebnerization of the skin of a patient who has a contracted regulatory B cell pool and possibly other factors that favor the onset of psoriasis, including dysfunctional regulatory T cells and a genetic background associated with psoriasis, could contribute to exceeding the threshold required for the induction of psoriasis.

A myriad of innate and adaptive immune cells stay under the influence of environmental (infectious, physical trauma) and genetic factors and play an important role in psoriasis. Innate immune cells can be activated by microbial products via Toll-like receptors leading to production of interferon-a by plasmocytoid dendritic cells, TNF, nitric oxide, IL-20 and IL-23 by TIP-dendritic cells, IL-8 by neutrophils and a battery of chemokines, and heat-shock-proteins and defensins by keratinocytes. Angiogenesis is promoted by angiogenic and connective tissue growth factors that are formed by activated keratinocytes. This activation of innate immune cells leads to homing of CLA+ CD4, CD8 T cells and NK-T cells to the skin and secretion of interferon-gamma, TNF, lymphotoxin, and IL-17 by these cells.2 The immune system has evolved regulatory mechanisms that normally constrain the activity of pro-inflammatory cells, such as regulatory CD4+ 25+ Foxp3+ natural Tregs and Foxp3 inducible Tregs (Tr1 and Th3 cells). Psoriatic CD4+ 25+ Foxp3+ Tregs have been shown to be impaired in their ability to suppress T cell proliferation. More recently a new regulatory IL-10+ B cell pool has been described.3 These cells have been shown to suppress T cell proliferation in vitro and inhibit allergic contact dermatitis in mice.14

Our report lacks definitive histopathological confirmation that the patient's rash is indeed psoriasiform. However, the diagnosis of a psoriasiform rash is most supported by the development of nail pitting on multiple fingers of both hands (Figure 1, only left hand depicted) that manifested in concert with the appearance of scaly erythematous hand plaques (Figure 2). Nail pitting may declare itself in other dermatological conditions such as atopic dermatitis, alopecia areata, hand eczema or trauma. The lack of pruritis and absence of hair loss argue against atopic dermatitis and alopecia areata. In addition, nail pitting in alopecia areata is usually more superficial and has a geometric grid-like distribution. Acute hand eczema presents occasionally with vesicles of the proximal nail fold and the hyponychium, irregular nail pitting and Beau's lines. The patient denied vesiculation and we did not appreciate Beau's lines. In addition, trauma may cause nail changes. However, it is very unlikely for physical trauma to induce a rash as we have seen in our patient. Trauma is much more likely to result in onychomadesis and subungual hemorrhage. Psoriasiform dermatitis of the hand and the nail appears to be clinically the most likely etiology of our patient's rash.

Figure 1.

Dorsal aspect of patient's left hand

Figure 2.

Palmar aspect of patient's left hand.

It is tempting to speculate that our patient has developed a psoriasiform rash, responsive to standard topical treatments of psoriasis, as a consequence of iatrogenically abrogated function of regulatory B cells and triggered by physical trauma and maybe introduction of Toll-like receptor activating pathogen-associated microbial patterns (PAMPs). Undoubtedly, additional predisposing factors like genetic predisposition and other environmental factors might be operational. A possible association of psoriasis and our patient's underlying ALPS cannot be entirely ruled out, although to date no such associations have been described in the literature. The rarity and our incomplete understanding of ALPS pose hurdles for answering this important question.

It can also be argued that depletion of regulatory B cells after treatment with rituximab is not the operational mechanism in the development of our patient's psoriasiform rash, but rather co-administration of IVIG may have induced the rash. IVIG is believed to cause anti-inflammatory effects by interacting with the Fc receptor of innate immune cells and to cause suppression of inflammatory mediators such as cytokines and chemokines, along with disruption of signaling to other inflammatory cells such as phagocytes and complement.15 IVIG therapy has been shown to be an effective treatment for some cases of psoriasis and other autoimmune diseases.1 Dermatologic side effects of IVIG that have been reported include eczematous dermatitis on hands/soles and nummular dermatitis.10 To our knowledge psoriasiform rashes have not been described in patients receiving IVIG.

We believe it is unlikely that the patient's psoriasiform rash may have been a result of IVIG treatment. First, the rash described in our case does not appear eczematous and was not pruritic. Second, the patient continued to receive IVIG after he was seen in our dermatology clinic and he had a good therapeutic response to super-potent steroid and calcipotriene ointments despite continuing IVIG infusions. Third, if the patient's rash was caused by IVIG one would expect a more symmetric distribution as described for eczematous IVIG-induced dermatitides and also dissemination to other skin areas as described in nummular dermatitis after IVIG therapy.

In stark contrast we feel that concomitant treatment with IVIG may have ameliorated the patient's psoriasiform rash and prevented spread to other non-koebnerized areas of skin. It is not surprising that IVIG, a therapeutic agent that may transduce inhibitory signals into Fcg-receptor bearing dendritic cells, histiocytes and other innate immune cells,16 has been described as second or third-line treatment in some cases of psoriasis.10 This is particularly convincing if we consider the important role of innate immune cells in the pathogenesis of psoriasis.

SUMMARY

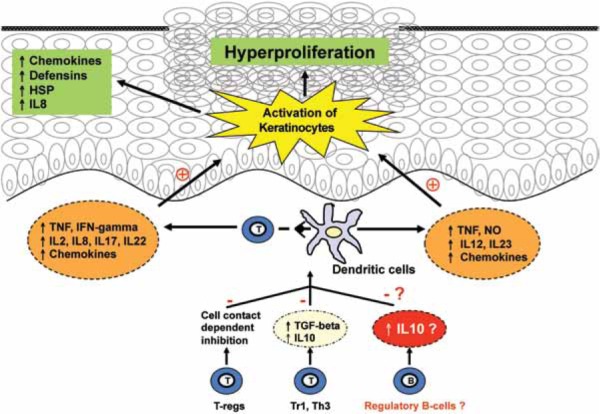

We report the case of a patient with ALPS and immune-thrombocytopenia who developed a psoriasis-like rash after undergoing B-cell depleting treatment for ITP. Based on recent studies that identify a subset of IL-10+ regulatory B cells we hypothesize that depletion of this cell type may have unleashed auto-reactive T cells, leading to the development of psoriasis (Figure 3). Co-treatment with IVIG, which has immunosuppressive properties, may have blunted the immune reaction that lead to psoriasis and restricted the rash to koebnerized areas of skin. Our report lacks experimental evidence to support this hypothesis. However, we feel that due to the very recent discovery of regulatory B cells we ought to bring this novel and interesting regulatory cell population to the attention of clinicians and scientists, fueling growing interest and further study of these cells in psoriasis and in other inflammatory dermatoses.

Figure 3.

A simplified overview of the pro-inflammatory and regulatory cellular network in psoriasis, illustrating the role of regulatory B cells. Interaction of conventional T cells with dendritic cells leads to secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, which further activate immune cells, recruit inflammatory cells, activate and induce proliferation of epithelial keratinocytes. Regulatory mechanisms like T-regs, Th3, Tr1 and possibly regulatory B cells inhibit this interaction and reduce inflammation in the skin. Dysfunction of regulatory B cells may lead to failure to contain inflammation and result in psoriasis in predisposed individuals. HSP, heat shock proteins; IL, interleukin; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; IFN, interferon; TGF, transforming growth factor; NO, nitric oxide.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This paper was presented as a poster presentation at the American Academy of Dermatology annual meeting in San Francisco, California in March, 2009 and the Ohio State University Medical Center Research Day in Columbus, Ohio in April, 2009. We thank Dr Carol Blanchong at Nationwide Children's Hospital, Columbus, Ohio, for her valuable contributions on the past medical history of the patient.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ADCC

antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity

- ALPS

autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome

- CVID

common variable immunodeficiency

- IVIG

intravenous immune globulin

- ITP

immune thrombocytopenia

- PAMP

pathogen-associated microbial patterns

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE The authors declare no conflicts or financial interest in any product or service mentioned in the manuscript, including grants, equipment, medications, employment, gifts, and honoraria.

REFERENCES

- 1.Griffiths C, Voorhees J. Psoriasis, T cells and autoimmunity. J R Soc Med. 1996;89:315–319. doi: 10.1177/014107689608900604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lowes M, Bowcock A, Krueger JG. Pathogenesis and therapy of psoriasis. Nature. 2007;445:866–873. doi: 10.1038/nature05663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fillatreau S, Gray D, Anderton SM. Not always the bad guys: B cells as regulators of autoimmune pathology. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:391–397. doi: 10.1038/nri2315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dass S, Vital E, Emery P. Development of psoriasis after B cell depletion with rituximab. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:2715–2718. doi: 10.1002/art.22811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edwards J, Szczepanski L, Szechinski J. Efficacy of B-cell-targeted therapy with rituximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2572–2581. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032534. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shanafelt T, Madueme H, Wolf RC, Tefferi A. Rituximab for immune cytopenia in adults: idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, and Evans syndrome. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2003;78:1340–1346. doi: 10.4065/78.11.1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wei A, Cowie T. Rituximab responsive immune thrombocytopenic purpura in an adult with underlying autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome due to a splice-site mutation (IVS7+2 T>C) affecting the Fas gene. Eur J Haematol. 2007;79:363–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2007.00924.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith M. Rituximab (monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody): mechanisms of action and resistance. Oncogene. 2003;22:7359–7368. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taguchi Y, Takashima S, Yoshida S. Psoriasis improved by intravenous immunoglobulin therapy. Intern Med. 2006;45:879–880. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.45.1704. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gurmin V, Mediwake R, Fernando M. Psoriasis: response to high-dose intravenous immunoglobulin in three patients. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:554–557. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04753.x. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gern J. Antiinflammatory activity of IVIG mediated through the inhibitory fc receptor. Pediatrics. 2002;110:467–468. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shaw T, Quan J, Totoritis M. B cell therapy for rheumatoid arthritis: the rituximab (anti-CD20) experience. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62(Suppl 2):ii55–ii59. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.suppl_2.ii55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moore KW, de Waal Malefyt R, Coffman RL, O'Garra A. Interleukin-10 and the interleukin-10 receptor. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:683–765. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yanaba K, Bouaziz J, Haas KM. A regulatory B cell subset with a unique CD1dhiCD5+ phenotype controls T cell-dependent inflammatory responses. Immunity. 2008;28:639–650. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.03.017. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kazatchkine M, Kaveri S. Immunomodulation of autoimmune and inflammatory diseases with intravenous immune globulin. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:747–755. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra993360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch J. Fc gamma receptors as regulators of immune response. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:34–47. doi: 10.1038/nri2206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]