Abstract

Canine leukocyte adhesion deficiency (CLAD) provides a unique large animal model for testing new therapeutic approaches for the treatment of children with leukocyte adhesion deficiency (LAD). In our CLAD model, we examined two different fragments of the human elongation factor 1α (EF1α) promoter (EF1αL, 1169 bp and EF1αS, 248 bp) driving expression of canine CD18 in a self-inactivating (SIN) lentiviral vector. The EF1αS vector resulted in the highest levels of canine CD18 expression in CLAD CD34+ cells in vitro. Subsequently, autologous CD34+ bone marrow cells from four CLAD pups were transduced with the EF1αS vector and infused following a nonmyeloablative dose of 200 cGy total body irradiation. None of the CLAD pups achieved levels of circulating CD18+ neutrophils sufficient to reverse the CLAD phenotype, and all four animals were euthanized due to infections within 9 weeks of treatment. These results indicate that the EF1αS promoter-driven CD18 expression in the context of a RRLSIN lentiviral vector does not lead to sufficient numbers of CD18+ neutrophils in vivo to reverse the CLAD phenotype when used in a nonmyeloablative transplant regimen in dogs.

Keywords: EF1α promoter, lentiviral vector, ex vivo gene therapy, CLAD, leukocyte adhesion, immunodeficiency

Introduction

Canine leukocyte adhesion deficiency (CLAD), the canine homologue of LAD-I in humans, is characterized by severe, recurrent bacterial infections leading to death within the first 6 months of life.1,2 CLAD animals are homozygous for the identical 107G→C nucleotide substitution in the CD18 gene, which results in a 36Cys→Ser amino acid substitution in the CD18 protein.3

In previous studies, we used the CLAD model to demonstrate that both γ-retroviral and foamy viral vector-mediated transfer of the canine CD18 gene can reverse the CLAD phenotype.4,5 However, both studies relied on the long terminal repeat (LTR) of the murine stem cell virus (MSCV) promoter to express the canine CD18 gene; in the γ-retroviral vector, the MSCV 5’LTR directed the expression of canine CD18, whereas in the foamy viral vector, an internal MSCV LTR promoter fragment directed canine CD18 expression.4,5

Recently, insertional mutagenesis from retroviral promoters, particularly the murine leukemia virus LTR promoter/enhancer, has emerged as a serious concern in hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy. In the gene therapy clinical trials for the treatment of X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency disease (X-SCID), and chronic granulomatous disease (CGD), insertional activation of nearby proto-oncogenes by a strong retroviral LTR promoter led to leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome, respectively.6,7 Subsequent research has demonstrated that replacement of retroviral LTR promoters by cellular promoters may reduce the risk of insertional activation from viral promoters/enhancers.8

The human elongation factor 1α (EF1α) has been shown to direct the expression of reporter genes in a variety of cell types, including neural and lymphoid cells.9 The EF1α promoter (nucleotides 373 to 1561) has also been shown to be a strong promoter in primary human CD34+ cells.10-13 When used within the context of a self-inactivating (SIN) lentiviral vector, EF1α promoter-driven EGFP expression was comparable to that of the MSCV LTR, the phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) promoter, and the composite CAG promoter (consisting of the CMV immediate early enhancer and the chicken β-actin promoter) in the human myeloid leukemia cell line, KG-1a.12 In addition, the EF1α promoter has been shown to induce ubiquitous and high level expression of human CD55 and CD59 in transgenic rabbits.14

The studies described above prompted us to test the efficacy of the human EF1α cellular promoter in a SIN lentiviral vector to direct canine CD18 expression in dogs with LAD.

Results and discussion

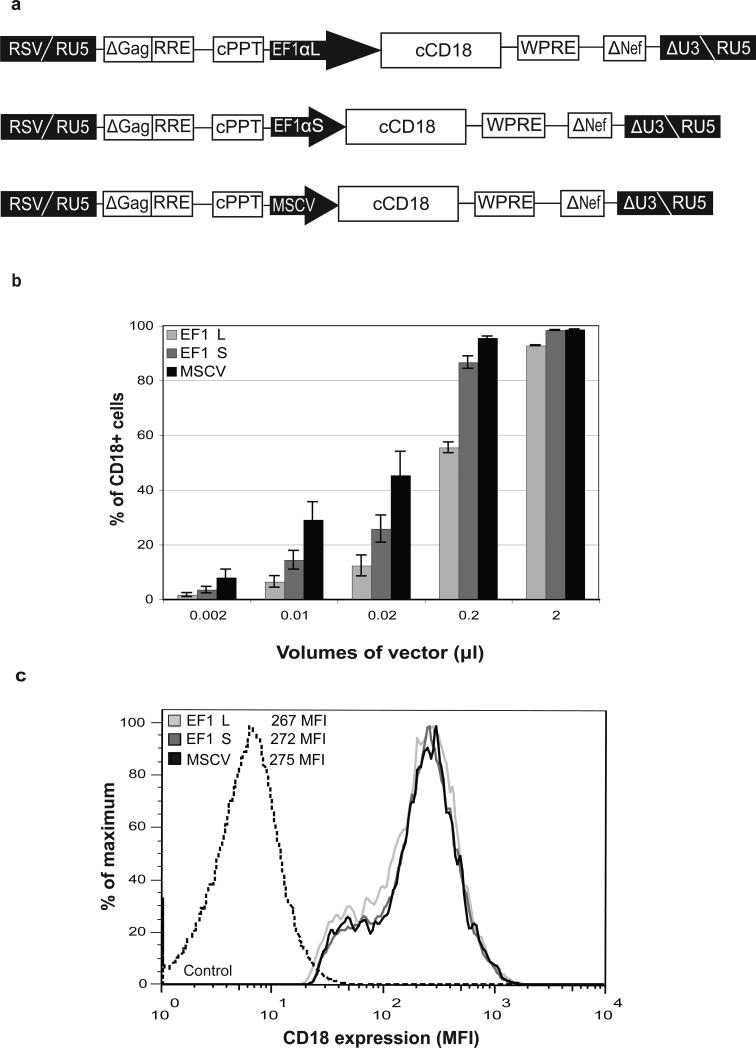

We constructed human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-based SIN lentiviral vectors expressing canine CD18 from two different lengths of the human EF1α promoter/enhancer - a 248 bp fragment consisting of nucleotides from 373 to 633 (EF1αS) and a 1169 bp fragment consisting of nucleotides from 373 to 1561 of the human EF1α gene (EF1αL)12,13 (Figure 1a). As a control, an MSCV promoter driving expression of canine CD18 was also constructed using the same lentiviral vector backbone, pRRLSIN.cPPT.WPRE. Lentiviral vectors were pseuodotyped with a vesicular stomatitis virus G-glycoprotein (VSV-G) envelope.

Figure 1.

Construction, and testing of lentiviral vectors. (a) Schematic of the vector constructs. EF1α, elongation factor 1α; MSCV, murine stem cell virus; cPPT, central polypurine tract; WPRE, woodchuck hepatitis virus post-transcriptional regulatory element; RRE, Rev-responsive element; RSV, Rous sarcoma virus. (b) Transduction efficiency in LAD EBV B-cells (ZJ). ZJ cells (2.5 × 105/well) were incubated with increasing volumes of each vector (240x concentrated) in RetroNectin™ coated, non-tissue culture treated, 24-well plates at 37°C. Following transduction, cells were analyzed for CD18 expression by flow cytometry on Day 5. The volumes of each concentrated vector (μl/well) are shown on the x-axis. The percentage of CD18+ cells is indicated on the y-axis. (c) Comparison of CD18 expression in ZJ cells. Mean fluorescence intensities (MFIs) of the three vectors transduced at 0.01 μl/well are shown. The MFI of an untransduced control is shown for comparison.

The CD18 subunit does not become surface expressed without the CD11 subunit; therefore, we used an EBV transformed B-cell line derived from an LAD patient (ZJ) to determine expression of CD18 from the three vectors. The ZJ LAD EBV B-cell line expresses the endogenous human CD11a leukocyte integrin subunit, but does not express the human CD18 subunit.15 Transfection or transduction of normal human or canine CD18 into LAD EBV B-cells has been shown previously to rescue the CD11a subunits and result in surface expression of the CD11a/CD18 complexes.3,16 When analyzed on Day 5 following a 16 h transduction with serial dilutions of each 240x concentrated vector, the EF1αS vector resulted in a higher percentage of CD18+ cells compared to the EF1αL vector at all concentrations tested. The MSCV promoter within the same vector backbone resulted in the highest percentage of CD18+ cells (Figure 1b). The titers, represented as transduction units per ml (TU/ml), were calculated for each vector in the linear range where up to 30% of the cells were CD18+. The EF1αS vector yielded titers three times higher than the EF1αL vector (4.3 × 108 vs 1.3 × 108 TU/ml). All three vectors yielded comparable levels of CD18 expression based on the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) values, although the MSCV vector had the highest titer (9.8 × 108 TU/ml). Thus, all three vectors expressed equivalent levels of CD18 in ZJ cells on a per cell basis (Figure 1c).

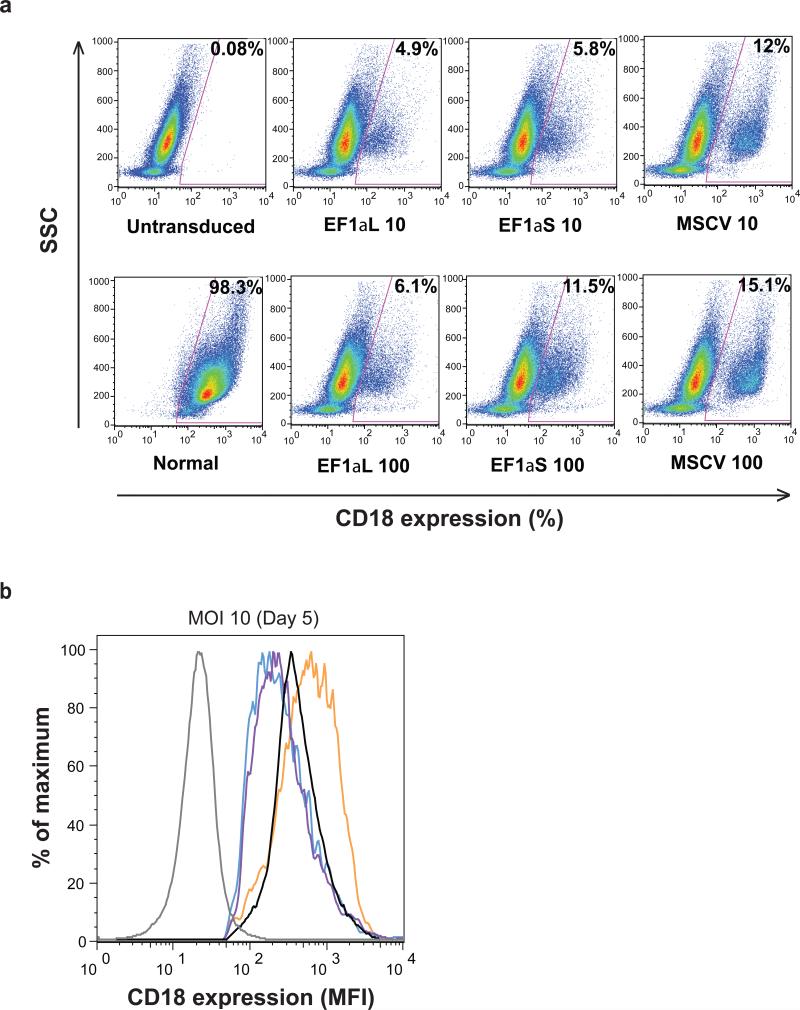

To determine the ability of the lentiviral vectors to transduce CD34+ cells, CLAD bone marrow CD34+ cells were incubated for 16 h with each of the vectors at multiplicities of infection (MOIs) of 10 and 100, and analyzed on Day 5 following transduction. Representative dot plots from a CLAD CD34+ transduction experiment are shown (Figure 2a). Untransduced CLAD CD34+ cells and normal canine CD34+ cells served as negative and positive controls, respectively. The EF1αS vector yielded higher transduction efficiencies (5.8% and 11.5%, at MOIs of 10 and 100, respectively) than the EF1αL vector (4.9% and 6.1%). Again, the MSCV vector resulted in the highest percentage of CD18+ cells (12% and 15.1%) (Figure 2a). Analysis of the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) based on CD18 expression in vector-transduced CD34+ cells indicated that the expression of CD18 from both the EF1α promoters were comparable, and similar to the CD18 expression in CD34+ cells from a normal dog (Figure 2b). The MSCV vector generated higher levels of CD18 expression than that observed on normal canine CD34+ cells (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Transduction of CLAD CD34+ cells with SIN lentiviral vectors expressing canine CD18. (a) CD34+ bone marrow cells (5 × 105/well) from CLAD pups were added to RetroNectin™ coated, non-tissue culture treated, 24-well plates. StemSpan SFEM + 10% FBS, along with 5 μg/ml of protamine sulfate, and a cytokine cocktail consisting of 50 ng/ml each of canine IL-6, canine SCF, human Flt3-L, human TPO, and human G-CSF were also added per well. Vectors were added at MOIs of 10 and 100. Plates were spinnoculated (2500 rpm, 32°C, 30 min) and incubated at 37°C. Following transduction, cells were analyzed for CD18 expression by flow cytometry on Day 5. The x-axis indicates CD18 expression, while the y-axis indicates the side scatter (SSC). The percentages of CD18+ cells are shown in the upper right-hand corner of each dot plot. (b) The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CD18 expression in CLAD CD34+ cells following transduction with the three vectors (Day 5). CD18+ cells were gated as indicated by the selected areas in Figure 2a. Each vector is shown as follows: EF1αL (purple), EF1αS (blue), and MSCV (orange). MFIs corresponding to an untransduced control (gray), and that of a normal dog (black) are shown for comparison.

To assess the ability of the EF1αS promoter within the context of a SIN lentiviral vector to direct canine CD18 expression on leukocytes in vivo, we used this vector in an ex vivo gene therapy protocol that we had used previously to test foamy viral vectors in the treatment of CLAD.5 We selected the EF1αS vector due to its higher titer and higher transduction efficiency in CLAD CD34+ cells compared to the EF1αL vector. Autologous bone marrow-derived CD34+ cells from four CLAD pups were transduced in a 16 h exposure to the RRLSIN.cPPT.EF1αS.cCD18.WPRE lentiviral vector plus cytokines on RetroNectin™. Following transduction, cells were harvested and infused into animals that had received a single, nonmyeloablative dose of 200 cGy TBI on the day prior to infusion to facilitate engraftment. All four CLAD pups were treated at approximately 7 weeks of age. Initial ex vivo transduction efficiency ranged from 4.1% to 8.9%, leading to an estimated range of 0.41 × 106 to 1.41 × 106 CD18+CD34+ cells/kg at the time of infusion (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of Cell Doses and Outcomes with Lentiviral Vector (LV), Foamy Viral Vector (FV), and γ-Retroviral (RV) Vector Transduced CD18+CD34+ cells infused into CLAD dogs

| Dog | CD18+ cells | CD18+CD34+ cells / kg | CD18+ PBL | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LV1 | 7.5% | 0.71 × 106 | 0.3% at 8 wks | Death at 8.4 wks |

| LV2 | 8.9% | 1.41 × 106 | 0.2% at 8 wks | Death at 9.0 wks |

| LV3 | 6.8% | 0.71 × 106 | 0.2% at 8 wks | Death at 7.7 wks |

| LV4 | 4.1% | 0.41 × 106 | 0.2% at 3 wks | Death at 3.4 wks |

| FV1 | 13.7% | 0.32 × 106 | 1.4% at 8 wks | Alive > 1 yr |

| FV2 | 24.6% | 0.42 × 106 | 2.4% at 8 wks | Alive > 1 yr |

| FV3 | 23.2% | 0.72 × 106 | 2.2% at 8 wks | Alive > 1 yr |

| FV4 | 22.2% | 0.75 × 106 | 0.8% at 8 wks | Alive > 1 yr |

| RV1 | 21.1% | 0.17 × 106 | 0.5% at 8 wks | Alive > 1 yr |

| RV2 | 11.6% | 0.61 × 106 | 0.3% at 8 wks | Alive > 1 yr |

Lentiviral vector used the EF1αS promoter to express canine CD18 cDNA; Foamy viral vector used the MSCV internal promoter to express canine CD18 cDNA; γ-Retroviral vector used the MSCV LTR to express canine CD18 cDNA.

Surface expression of CD18 was assessed on peripheral blood leukocytes prior to infusion, and at weekly intervals following infusion. We had previously demonstrated that even low levels (0.5%) of CD18+ peripheral blood leukocytes (PBL) could reverse or attenuate the CLAD phenotype.17,18 However, none of the EF1αS promoter lentiviral vector-treated dogs had greater than 0.3% CD18+ peripheral blood leukocytes at any time following infusion, and all four succumbed to infection by 9 weeks following treatment.

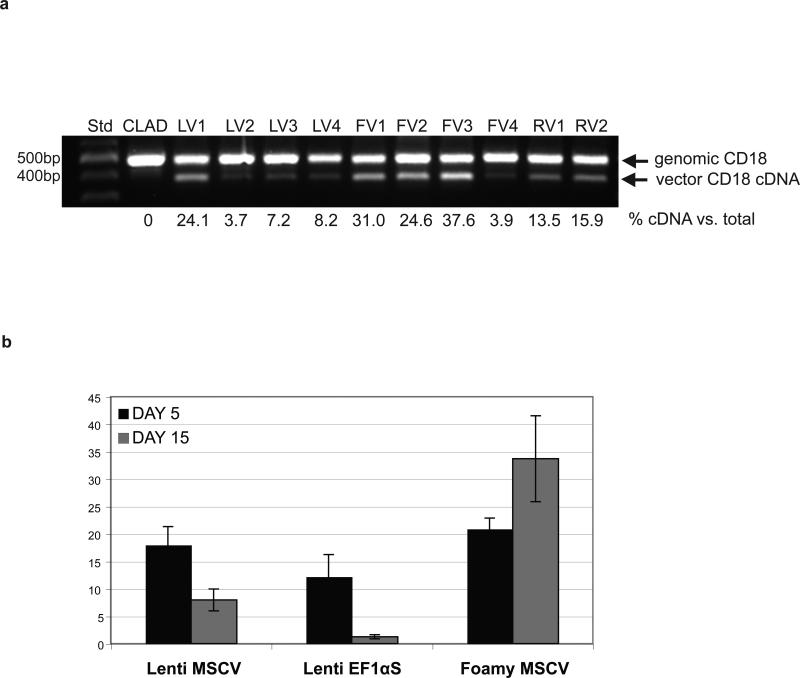

Despite the very low levels of CD18+ leukocytes in the peripheral blood following infusion of the vector-transduced autologous CD34+ cells, vector integrated CD18 cDNA could be amplified readily from the genomic DNA extracted from the peripheral blood leukocytes of all four dogs, suggesting that the amount of the vector DNA present in the peripheral blood leukocytes of the treated dogs did not correlate with very low levels of surface CD18 expression (Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

(a) Genomic PCR from peripheral blood leukocytes for canine CD18 cDNA integration. Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood leukocytes 8 weeks (3 weeks for dog LV4) following infusion of vector-transduced cells for the lentiviral vector (LV1-4) and at 12 weeks following infusion for the foamy viral vector (FV1-4) and the γ-retroviral vector (RV1,2). 100 ng of genomic DNA was used as a template to assess the integration of canine CD18 cDNA by PCR. Std, 100-bp size standard; CLAD, untreated CLAD dog. (b) Change in the percentage of CD18+ cells between Day 5 and Day 15 following transduction. CLAD CD34+ cells transduced with the previously stated cytokine cocktail in RetroNectin™ coated 24-well plates, analyzed for CD18 expression on Day 5 or after an additional 10 days in growth factors to differentiate the cells down the myeloid lineage (Day 15).

Previously, we reported that ex vivo gene therapy in CLAD CD34+ cells using a γ-retroviral vector with the MSCV LTR, and a foamy virus vector incorporating the MSCV internal promoter, resulted in sufficient surface expression of canine CD18 to reverse the CLAD phenotype using the same nonmyeloablative conditioning regimen of 200 cGy TBI used in this study.4,5 In the current study, the human EF1αS promoter (EF1α promoter without intron 1) within the context of a SIN lentiviral vector did not result in sufficient numbers of CD18+ neutrophils in vivo to reverse the CLAD phenotype.

To investigate this failure of the EF1αS promoter in a lentiviral vector to reverse the CLAD phenotype, we compared the differences of the lentiviral vector with the foamy viral vector and the γ-retroviral vector (Table 1). Although the transduction efficiency of the foamy viral vector and the γ-retroviral vector were higher than the lentiviral vector, comparable numbers of CD18+CD34+ cells/kg were infused due to the higher numbers of CD34+ cells used with the lentiviral vector treated animals (Table 1). Also, the percentages of CD18+ peripheral blood leukocytes were only slightly higher in the γ-retroviral vector treated dogs compared to the lentiviral vector treated animals. The amount of DNA copies of CD18 cDNA were nearly commensurate with the levels seen in the γ-retroviral vector treated animals in three lentiviral vector treated dogs, and actually exceeded the levels seen in the γ-retroviral vector treated dogs in one case namely, LV1 (Figure 3a).

To pursue this question of whether the EF1αS promoter in the lentiviral vector might lose activity over time, we compared CLAD CD34+ cells transduced with the EF1αS promoter in the lentiviral vector to CLAD CD34+ cells transduced with the MSCV promoter in the same lentiviral vector backbone, and to CLAD CD34+ cells transduced with the foamy viral vector incorporating an internal MSCV promoter (Figure 3b). CD18+ expression at two time points was compared: on Day 5 following the 16 h transduction, and on Day 15 following transduction and further incubation with growth factors (cG-CSF, c-SCF, Flt3 Ligand). There was a marked decrease in CD18 expression in CD34+ cells transduced with the EF1αS vector compared to the MSCV lentiviral vector following the two-week expansion (Figure 3b). This raises the question as to whether the EF1αS promoter in the lentiviral vector is being silenced. There is evidence that the EF1αS promoter in a lentiviral vector is prone to transcriptional gene silencing.19

Our future studies are directed towards improving vector design and efficiency of transduction, as well as identifying other cellular promoters capable of directing consistent, stable, and therapeutically relevant levels of CD18 expression in vivo.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research. We wish to thank William Telford and Veena Kapoor, NCI, for flow cytometry assistance.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest statement

The authors have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Trowald-Wigh G, Hakansson L, Johannisson A, Norrgren L, Hard af Segerstad C. Leucocyte adhesion protein deficiency in Irish setter dogs. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1992;32:261–280. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(92)90050-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Creevy KE, Bauer TR, Jr., Tuschong LM, Embree LJ, Colenda L, Cogan K, et al. Canine leukocyte adhesion deficiency colony for investigation of novel hematopoietic therapies. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2003;94:11–22. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2427(03)00057-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kijas JM, Bauer TR, Jr., Gafvert S, Marklund S, Trowald-Wigh G, Johannisson A, et al. A missense mutation in the β2 integrin gene (ITGB2) causes canine leukocyte adhesion deficiency. Genomics. 1999;61:101–107. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.5948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauer TR, Jr., Hai M, Tuschong LM, Burkholder TH, Gu YC, Sokolic RA, et al. Correction of the disease phenotype in canine leukocyte adhesion deficiency using ex vivo hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy. Blood. 2006;108:3313–3320. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-006908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bauer TR, Jr., Allen JM, Hai M, Tuschong LM, Khan IF, Olson EM, et al. Successful treatment of canine leukocyte adhesion deficiency by foamy virus vectors. Nat Med. 2008;14:93–97. doi: 10.1038/nm1695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hacein-Bey-Abina S, Von Kalle C, Schmidt M, McCormack MP, Wulffraat N, Leboulch P, et al. LMO2-associated clonal T cell proliferation in two patients after gene therapy for SCID-X1. Science. 2003;302:415–419. doi: 10.1126/science.1088547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ott MG, Schmidt M, Schwarzwaelder K, Stein S, Siler U, Koehl U, et al. Correction of X-linked chronic granulomatous disease by gene therapy, augmented by insertional activation of MDS1-EVI1, PRDM16 or SETBP1. Nat Med. 2006;12:401–409. doi: 10.1038/nm1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zychlinski D, Schambach A, Modlich U, Maetzig T, Meyer J, Grassman E, et al. Physiological Promoters Reduce the Genotoxic Risk of Integrating Gene Vectors. Mol Ther. 2008;16:718–725. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim DW, Uetsuki T, Kaziro Y, Yamaguchi N, Sugano S. Use of the human elongation factor 1 alpha promoter as a versatile and efficient expression system. Gene. 1990;91:217–223. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90091-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ye ZQ, Qiu P, Burkholder JK, Turner J, Culp J, Roberts T, et al. Cytokine transgene expression and promoter usage in primary CD34+ cells using particle-mediated gene delivery. Hum Gene Ther. 1998;9:2197–2205. doi: 10.1089/hum.1998.9.15-2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mikkola H, Woods NB, Sjogren M, Helgadottir H, Hamaguchi I, Jacobsen SE, et al. Lentivirus gene transfer in murine hematopoietic progenitor cells is compromised by a delay in proviral integration and results in transduction mosaicism and heterogeneous gene expression in progeny cells. J Virol. 2000;74:11911–11918. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.24.11911-11918.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramezani A, Hawley TS, Hawley RG. Lentiviral vectors for enhanced gene expression in human hematopoietic cells. Mol Ther. 2000;2:458–469. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2000.0190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salmon P, Kindler V, Ducrey O, Chapuis B, Zubler RH, Trono D. High-level transgene expression in human hematopoietic progenitors and differentiated blood lineages after transduction with improved lentiviral vectors. Blood. 2000;96:3392–3398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taboit-Dameron F, Malassagne B, Viglietta C, Puissant C, Leroux-Coyau M, Chereau C, et al. Association of the 5'HS4 sequence of the chicken beta-globin locus control region with human EF1 alpha gene promoter induces ubiquitous and high expression of human CD55 and CD59 cDNAs in transgenic rabbits. Transgenic Res. 1999;8:223–235. doi: 10.1023/a:1008919925303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bauer TR, Jr., Miller AD, Hickstein DD. Improved transfer of the leukocyte integrin CD18 subunit into hematopoietic cell lines by using retroviral vectors having a gibbon ape leukemia virus envelope. Blood. 1995;86:2379–2387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Back AL, Kwok WW, Adam M, Collins SJ, Hickstein DD. Retroviral-mediated gene transfer of the leukocyte integrin CD18 subunit. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;171:787–795. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)91215-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bauer TR, Jr., Creevy KE, Gu YC, Tuschong LM, Donahue RE, Metzger ME, et al. Very low levels of donor CD18+ neutrophils following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation reverse the disease phenotype in canine leukocyte adhesion deficiency. Blood. 2004;103:3582–3589. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-4008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gu YC, Bauer TR, Sokolic RA, Hai M, Tuschong LM, Burkholder T, et al. Conversion of the severe to the moderate disease phenotype with donor leukocyte microchimerism in canine leukocyte adhesion deficiency. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;37:607–614. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang AH, Stephan MT, Sadelain M. Stem cell-derived erythroid cells mediate long-term systemic protein delivery. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:1017–1021. doi: 10.1038/nbt1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]