Abstract

OBJECTIVE

The purpose of this study was to determine if a prescription review service, at the time of discharge, enhances the accuracy and safety of prescriptions written at an academic pediatric hospital.

METHODS

The study took place over a 30-day period and included prescriptions written for patients being discharged from the General Pediatric and Pediatric Intensive Care Services at the University of Maryland Hospital for Children, a 120-bed academic pediatric hospital. Discharge prescriptions were faxed to the Inpatient Pediatric Pharmacy where they were reviewed by a pediatric clinical pharmacist. Specific review criteria were aimed at detecting prescribing errors that included patient identification, medication selection, dosing, and therapy omission. A prescriber was notified via alpha page when errors were identified and advised on corrective measures. Interventions were compiled and analyzed to determine the overall impact of the discharge prescription review program.

RESULTS

Over the 30-day period, 74 discharge prescriptions were reviewed by a pediatric clinical pharmacist. At least one prescribing error was detected in 81% of the prescriptions reviewed. Overall, 101 prescribing errors were documented and included patient identification, medication selection and dose calculation errors. The estimated cost-savings attributed to the interventions is approximately $7670.

CONCLUSION

Through the discharge prescription review program, the pediatric clinical pharmacists were able to make interventions on the majority of prescriptions reviewed. The types of errors that required interventions have been identified as potential sources for major medication errors in the pediatric population. We concluded that the review of discharge prescriptions by a pediatric clinical pharmacist was an effective method of preventing prescribing errors in the pediatric environment.

Keywords: discharge, medication error, medication safety, pediatric, pharmacy, prescribing error, prescription

INTRODUCTION

The pediatric population has unique needs that require special considerations in the provision of health care and the prescribing of medications. Medication errors are the most common iatrogenic cause of morbidity and mortality among hospitalized pediatric patients.1,2 Medication errors, especially those with the potential to cause direct patient harm, are three times more likely to occur in the pediatric population compared to the adult population.3 The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Health Care Organizations stated in its 2005 National Patient Safety Goals (NPSG) an initiative to “accurately and completely reconcile [patient] medications across the continuum of care.” The most updated 2008 NPSG extend this continuum of care to include the outpatient setting as well.4,5 While measures have been implemented at our institution to enhance the safety and accuracy of inpatient pediatric prescriptions, discharge prescriptions are dispensed without formal review by a pediatric clinical pharmacist. The objective of this study is to evaluate the ability of a pharmacist discharge prescription review program to enhance the accuracy and safety of prescriptions written for pediatric patients as they are discharged from the hospital. A secondary objective is to determine if increasing involvement of the Department of Pharmacy in the patient discharge process would promote continuity of care between the inpatient and outpatient settings.

BACKGROUND

Several factors contribute to the incidence of prescribing errors in pediatric patients.6 The spectrum of patients encompassed in the category “pediatric” includes patients from birth to 18 years of age. This wide age span represents vast physiologic, metabolic, and pharmacokinetic diversity, all of which significantly impact drug dosing, pharmacodynamics, and therapeutic regimens.

A potential cause of prescribing errors in pediatrics is the need for weight-based or body surface area-based dosing for many commonly prescribed medications. Whereas standard drug dosing is commonly used in the adult setting, the variability in pediatric developmental pharmacology and pharmacokinetics increases the complexity of therapy in this population. The practice of calculating dose based on weight or body surface area has been shown to increase the likelihood of dosing errors. It has been estimated that prescriptions written for pediatric patients account for about 70% of all prescribing errors associated with dose calculations.7 One of the most common pediatric calculation errors is the ten-fold error. This occurs when a decimal place or standardized unit of measurement is misinterpreted resulting in either over- or under-dosing. Weight or body surface area-based dosing can also lead to errors if pounds or kilograms are documented as values that have been incorrectly converted or misinterpreted and are subsequently used when calculating drug doses.

Another potential for prescribing errors results from a lack of commercially available pediatric formulations for commonly used medications. The lack of an appropriate formulation requires the pharmacist to extemporaneously compound an adult product in order to create a formulation suitable for pediatric administration, more specifically oral suspensions or solutions. If a practitioner is unfamiliar with medications that require reformulation and is unaware of their resulting concentrations there is an increased potential for misinterpretation, which can lead to dosing errors and subsequent patient harm. Dispensing these medications can also result in errors if the outpatient pharmacy is unfamiliar with extemporaneous compounding formulas or appropriate compounding techniques. Although references that provide compounding instructions are available, there is a limited number of specialty outpatient compounding pharmacies that can correctly prepare these formulations; hence, obtaining medications that require reformulation can be difficult.8

Increasing pharmacy involvement in direct patient care has been shown to reduce prescribing errors in both the inpatient and outpatient settings. The review of inpatient prescriptions by a clinical pharmacist, the introduction of the clinical pharmacist specialist, and point-of-care pharmacists have enhanced the use of pharmacy services and the involvement of pharmacists in the prescribing and management of inpatient drug therapy.9,10 Programs such as Computer Physician Order Entry (CPOE) and Medication Reconciliation have also benefited from pharmacy input.11–13

At the time of patient discharge, pharmacy-coordinated discharge medication counseling and prescription review programs have increased pharmacy-patient involvement and reduced discharge prescribing errors.14–19 Voirol and colleagues reported that a discharge medication service offered by a pediatric pharmacy team had a positive impact on patient education and medication adherence.20 Sexton et al. surveyed chief pharmacists in hospitals in the United Kingdom to assess the involvement of pharmacy services at the time of patient discharge. They found that discharge prescription verification by an inpatient pharmacist occurred in approximately 45% of hospitals surveyed.21 In a randomized, controlled trial, Stowasser et al. evaluated the impact of a pharmacy medication liaison service at the time of patient discharge. They found that patients who used the services had fewer subsequent health care visits and a reduction in the number of readmissions to the hospital. 22

METHODS

The study was reviewed and approved by the University of Maryland Medical Center Investigational Review Board and a waiver of informed consent was granted. The discharge prescription review program took place over a 30-day period from March 2007 to April 2007. The Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, which is covered by a point-of-care pharmacist who assists in discharge medication planning, and the Labor and Delivery and Mother/Baby Units, which are comprised of mostly adult patients, were excluded.

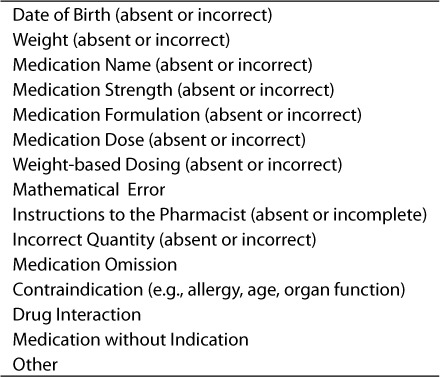

The intent of our study was to determine the impact of the discharge prescription review program based on our ability to ensure that prescriptions were written in an accurate manner, thus promoting effective and safe medication therapy. Our definition of prescription safety and accuracy was derived from Hepler and Strand's proposed roles and responsibilities of pharmacists in identifying, resolving and preventing mediation-related errors.23 These definitions included identifying medication use without an indication, untreated indications, improper drug selection, sub-therapeutic dosing, overdosing, and drug interactions.23 Additionally, patient identifiers, such as date of birth, as well as weight-based dosing for pediatric prescriptions were incorporated as recommended by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Health Care Organizations.24 These standards and proposals were used when compiling the prescription review criteria used by the pediatric clinical pharmacists in this study (Table 1). The review criteria represent significant interventions for prescribing errors that could potentially lead to inappropriate or sub-optimal medication therapy and/or possible adverse events.

Table 1.

Items that were assessed by a pharmacist in reviewing a discharge prescription

The Pediatric House Staff on service during the study period was educated during scheduled meetings on the appropriate technique for writing pediatric discharge prescriptions. These techniques were based upon the University of Maryland Medical Center Policies and Procedures regarding the writing of pediatric prescriptions. Practitioners were also provided pediatric drug dosing guides and a list of commonly used pediatric drug references. The prescribing guide was compiled by the Inpatient Pediatric Pharmacy and consisted of the most commonly prescribed pediatric medications, weight-based dosing formulas, common indications, and drug information including dosage forms and concentrations. Practitioners were also educated on the use of pre-printed pediatric discharge prescription blanks as mandated by the institution's Policies and Procedures. The prescription blanks are specially formatted to prompt the prescriber to include the patient's date of birth, weight and other pertinent patient identifiers as well as calculating the weight-based dosing for dose verification.

Pediatric discharge prescriptions were included in the study analysis if they were written by a practitioner at the Hospital for Children during the 30-day period. Prescriptions were faxed to the inpatient pharmacy and were reviewed by pediatric clinical pharmacists. The pharmacists were educated during a monthly staff meeting on the criteria used to evaluate each prescription and appropriate intervention methods to use in the event an error was detected. Prescriptions were reviewed using specific criteria aimed at detecting and reducing prescribing errors that are commonly seen in pediatric prescriptions. These criteria included date of birth, weight, dose calculations, drug selection and formulation, and length of therapy. Standard pediatric drug references and hospital computerized patient data were used to analyze each discharge prescription for patient information, evaluation of therapy and dose verification. Computerized inpatient medication profiles were used to determine the presence of possible medication omissions. The prescriber was notified by alpha page when errors were identified and instructed to contact the Pediatric Pharmacy for recommendations on corrective measures.

RESULTS

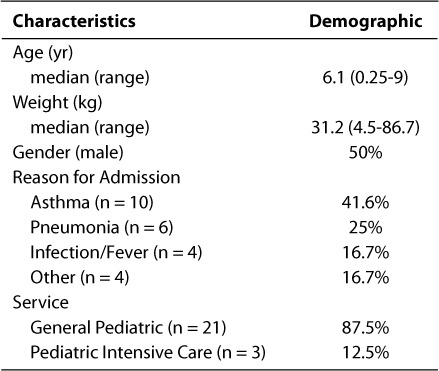

During the 30-day study period, a total of 74 discharge prescriptions for 24 patients were reviewed by a pediatric clinical pharmacist. The average number of prescriptions was three per patient, with a range of 1 to 9 prescriptions. The patient demographics, including age, weight, and reasons for hospitalization are listed in Table 2. Most of the patients were between the ages of 1 and 5 years and weighed between 10.1 kg and 20 kg. Most of the patients were discharged from the General Pediatric floor with a primary diagnosis of asthma exacerbation.

Table 2.

Study patient characteristics, reason for admission and medical service

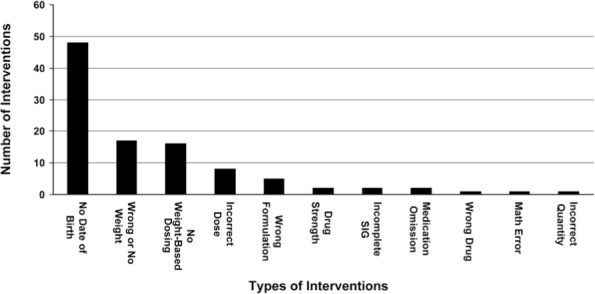

Of the 74 prescriptions, 81% contained at least one error as defined by the review criteria. Overall, 101 prescribing errors were detected and documented, with the majority of errors pertaining to pertinent patient information, dose calculations, or specific drug information such as concentration or formulation. A summary of the resulting interventions is provided in the Figure. Approximately 48% of interventions involved discharge prescriptions written without the patient's date of birth. This is considered an important factor in patient identification, assessment of drug dosing, and selection of an appropriate dosage formulation. Approximately 17% of discharge prescriptions lacked the patient's weight or appropriate weight-based dosing, both important components in dose verification. Examples of pharmacist-documented interventions include a prescription written for Dornase Alfa (Pulmozyme, Genentech, Inc.) instead of Budesonide (Pulmicort, AstraZeneca) in a patient being discharged following an exacerbation of asthma, a prescription for Amoxicillin with a calculation error resulting in a 5-fold overdose, and the omission of a discharge prescription for Azithromycin for the remainder of a 5-day course of therapy. Also of note was the lack of compliance with the use of the University of Maryland Hospital for Children pediatric discharge prescription blanks. Of the prescriptions reviewed, only 30% were written on the appropriate prescription blanks; of those 30%, only one prescription contained weight-based dosing calculations.

Figure.

Type and number of interventions.

Pharmacy interventions were logged in the institution's computerized database for tracking and assessing pharmacy interventions. Pharmacist interventions were entered into the PharmacyOneSource database (Quantifi; Bellevue, WA), and cost-savings were allocated for each intervention. The software is programmed to use a value of $2500 per adverse event to account for variation in adverse drug event (ADE) severity and associated morbidities. To identify cost-savings assigned to individual pharmacist interventions, the program uses a formula dividing the cost of the ADE by the prevalence rate, resulting in a baseline savings of $76 per intervention. Interventions are stratified into cost categories based on the overall clinical impact ranging from $48 to $200 per intervention.25 Based on the Pharmacy-OneSource Quantifi method of estimation, the total cost-savings accumulated from the 101 interventions made during the study program is estimated at approximately $7670.

DISCUSSION

After reviewing the data, we concluded that the discharge prescription review program allowed the pediatric clinical pharmacists to make interventions on the majority of prescriptions reviewed. A significant number of the interventions directly related to pertinent patient identifiers, dose calculations, incorrect prescribed medication and information needed for the correct selection of dosage formulation. These types of errors have been identified extensively in the literature as potential sources for major medication errors in the pediatric population. The review of the discharge prescriptions resulted in the correction of several dosing and drug selection errors that may have resulted in sub-optimal drug therapy or possible detrimental health-related consequences. Our study program produced positive results similar to published literature regarding the implementation of similar pharmacy discharge programs at other institutions. We recognize that in addition to the prescription review program, further education of pediatric medical staff and encouraging compliance with the use of standardized, pre-printed pediatric discharge prescriptions may also be an effective strategy for the prevention of further discharge prescribing errors. As a result of the number and types of interventions we were able to make, we conclude that the review of discharge prescriptions by a pediatric clinical pharmacist is an effective method of preventing prescribing errors.

While the preliminary data appear promising, several limitations encountered during this study need to be considered. One primary limitation was that not all discharge prescriptions were faxed to the inpatient pharmacy for review. The number of prescriptions reviewed during the 30-day period represents only a fraction of patients discharged from the University of Maryland Hospital for Children. The reasons for this disparity may stem from the study program being initiated during the latter portion of the medical resident year. Because the medical residents were not accustom to faxing the discharge prescriptions to pharmacy, introducing this new practice at the latter end of the resident year may have made it difficult for most to incorporate this practice into their daily routines. A second limitation was difficulty educating the pediatric medical staff due to rotating schedules and various shifts of the practitioners, nursing staff and pharmacists. Pharmacy staffing restraints may have also limited our study. The pharmacist shortage experienced at the time of the program and concerns regarding increasing workload may have negatively impacted the duration and extent of the participation of the pediatric clinical pharmacists in the study. Another concern was the lack of compliance with the use of the standard pediatric discharge prescriptions. These specialized prescription blanks are intended to prompt the prescriber to include all pertinent patient identifiers and perform any calculations needed to verify dose accuracy. It can be postulated that if more prescribers consistently used these prescription blanks when writing pediatric discharge prescriptions, medication errors could potentially be avoided.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The results from this project were presented at the 26th Annual Eastern States Conference for Pharmacy Residents and Preceptors in Baltimore, MD, May 10th, 2007. The authors would like to thank the pediatric clinical pharmacists, the Inpatient Pharmacy Staff and Medical Staff of the University of Maryland Hospital for Children for their assistance in this project and for their dedication to improving patient care.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ADE

adverse drug event

- CPOE

computer physician order entry

- NPSG

National Patient Safety Goals

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE The authors declare no conflicts or financial interest in any product or service mentioned in the manuscript, including grants, equipment, medications, employment, gifts, and honoraria.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hicks RW, Becker SC, Cousins DD. Harmful medication errors in children: a 5-year analysis of data from the USP's MEDMARX® program. J Periatr Nurs. 2006;21:290–298. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghaleb MA, Barber N, Franklin BD. Systematic review of medication errors in pediatric patients. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40:1766–1776. doi: 10.1345/aph.1G717. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sullivan JE, Buchino JJ. Medication errors in pediatrics–the octopus evading defeat. J Surg Oncol. 2004;88:182–188. doi: 10.1002/jso.20126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organization. Using medication reconciliation to prevent errors. Sentinel Event Alert. 2006:35. www.joint-commission.org. Accessed June 30 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organization. 2008 National Patient Safety Goals Hospital Program. www.jointcommission.org. Accessed June 30 2008. [PubMed]

- 6.Koren G. Trends of medication errors in hospitalized children. J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;42:707–710. doi: 10.1177/009127002401102614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kozer E, Berkovitch M, Koren G. Medication errors in children. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2006;53:1155–1168. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bormel G, Valentine JG, Williams RL. Application of USP-NF standards to pharmacy compounding. IJCP. 2003;7:361–663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaboli PJ, Hoth AB, McClimon BJ. Clinical pharmacists and inpatient medical care: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:955–964. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.9.955. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buck M, Connor JJ, Snipes CJ. Comprehensive pharmaceutical services for pediatric patients. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1993;50(1):78–84. et al. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Varkey P, Cunningham J, O'Meara J. Multidisciplinary approach to inpatient medication reconciliation in an academic setting. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2007;64:850–854. doi: 10.2146/ajhp060314. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vira T, Colquhoun M, Etchells E. Reconcilable differences: correcting medication errors at hospital admission and discharge. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15:122–126. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2005.015347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang JK, Herzog NS, Kaushal R. Prevention of pediatric medication errors by hospital pharmacists and the potential benefit of computerized physician order entry. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e77–85. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0034. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al-Rashed SA, Wright DJ, Roebuck N. The value of inpatient pharmaceutical counseling to elderly patients prior to discharge. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;54:657–664. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2002.01707.x. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duguid M, Gibson M, O'Doherty R. Review of discharge prescriptions by pharmacists integral to continuity of care. J Pharm Pract Res. 2002;32:94–95. et al. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Griffith NL, Schommer JC, Wirsching RG. Survey of inpatient counseling by hospital pharmacists. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1998;55:1127–1133. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/55.11.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schnipper JL, Kirwin JL, Cotugno MC. Role of pharmacist counseling in preventing adverse drug events after hospitalization. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:565–71. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.5.565. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cameron B. The impact of pharmacy discharge planning on continuity of care. Can J Hosp Pharm. 1994;47:101–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whitty JA, Green B, Cottrell WN. A study to determine the importance of ward pharmacists reviewing discharge prescriptions. Aust J Hosp Pharm. 2001;31:300–302. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Voirol P, Kayser SR, Chang CY. Impact of pharmacists' interventions on the pediatric discharge medication process. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;3810:1597–1602. doi: 10.1345/aph.1E087. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sexton J, Ho YJ, Green CF. Ensuring seamless care at hospital discharge: a national survey. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2000;25:385–393. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2710.2000.00305.x. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stowasser DA, Stowasser M, Collins DM. A randomized controlled trial of medication liaison services - patient outcomes. J Pharm Pract Res. 2002;32:122–140. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hepler CD, Strand LM. Opportunities and responsibilities in pharmaceutical care. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1990;47:533–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Critical Access Hospital 2006 Medication Management. www.jointcommission.org. Accessed June 30 2008.

- 25.PharmacyOneSource® (formerly Health-prolink®) Quantifi™ Intervention Cost Savings Justification. http://www.healthprolink.com/documents/CostSavings.htm. Accessed June 30 2008.