Abstract

In April 2009, the International Life Sciences Institute (ILSI) Health and Environmental Sciences Institute’s (HESI) Developmental and Reproductive Toxicology Technical Committee held a two-day workshop entitled “Developmental Toxicology—New Directions.” The third session of the workshop focused on ways to refine animal studies to improve relevance and predictivity for human risk. The session included five presentations on: (1) considerations for refining developmental toxicology testing and data interpretation; (2) comparative embryology and considerations in study design and interpretation; (3) pharmacokinetic considerations in study design; (4) utility of genetically modified models for understanding mode-of-action; and (5) special considerations in reproductive testing for biologics. The presentations were followed by discussion by the presenters and attendees. Much of the discussion focused on aspects of refining current animal testing strategies, including use of toxicokinetic data, dose selection, tiered/triggered testing strategies, species selection, and use of alternative animal models. Another major area of discussion was use of non-animal-based testing paradigms, including how to define a “signal” or adverse effect, translating in vitro exposures to whole animal and human exposures, validation strategies, the need to bridge the existing gap between classical toxicology testing and risk assessment, and development of new technologies. Although there was general agreement among participants that the current testing strategy is effective, there was also consensus that traditional methods are resource-intensive and improved effectiveness of developmental toxicity testing to assess risks to human health is possible. This article provides a summary of the session’s presentations and discussion and describes some key areas that warrant further consideration.

Keywords: refined study designs, testing strategies, developmental toxicology, safety assessment

INTRODUCTION

The purpose of this session was to evaluate current developmental toxicity study designs and possible refinements of testing strategies to maximize relevance for human safety assessment. As with all nonclinical toxicology testing, the objective of developmental toxicity testing is to determine the potential for human risk, in this case risk to the developing fetus following in utero exposure, through testing in animal models. The greater confidence we have in the relevance of these animal models to humans, the greater confidence we will have in the prediction of human risk.

Embryo–fetal developmental toxicity studies (i.e., Segment II or teratology studies) are required for the registration of new pharmaceutical and chemical products. These requirements are defined in guidance documents from the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) for chemicals, and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) for pharmaceuticals. Traditionally, developmental toxicity testing for both chemicals and pharmaceuticals has included studies in rodents (typically rats) and nonrodents (typically rabbits). Following maternal administration of test article during the period of major organogenesis, near-term fetuses are evaluated for viability, growth, and structural abnormalities. Evaluation of maternal toxicity is generally limited to mortality, clinical signs of toxicity, body weight/body weight gain, and food consumption. Additional endpoints may be added on a case-by-case basis, but are not common. Doses are typically selected based on maternal toxicity, where the high dose is expected to produce some adverse maternal effects (e.g., reductions in body weight gain), without mortality. These study designs and endpoints have remained largely unchanged for more than 40 years.

This session focused on ways to refine or optimize current animal studies to improve relevance and predictivity for human risk. The session included five presentations followed by discussion of predetermined questions, as well as open discussion. The presentation topics included: (1) an overview presentation of general considerations for refining developmental and reproductive toxicology (DART) testing and data interpretation; (2) comparative embryology and considerations in study design and interpretation; (3) pharmacokinetic considerations in study design—a case study of perfluoroalkyl acids (PFAAs); (4) utility of genetically modified animal models for understanding mode-of-action; and (5) special considerations in reproductive testing for biologics.

This manuscript is intended to provide a general summary of the presentations and discussion, and to identify key issues that warrant additional discussion and/or research.

Presentation 1: Overview: Special Considerations in Refining Existing DART study designs and data interpretation [Goal: Better extrapolation to human risk]. Presented by: Dr. Tacey White, GlaxoSmithKline

Using a number of specific examples, Dr. White described how available information on the compound of interest can/should be used when developing testing strategies, designing studies, defining mechanisms, and interpreting data. Considerations include known biologic activity (e.g., both target and off-target pharmacology for drugs), interspecies comparisons of pharmacology and metabolism, comparative embryology, and toxicokinetics considerations. Knockout and transgenic animal models can provide valuable information regarding the importance of a specific pathway in development and hence, the potential for developmental toxicity (and even potential outcomes), when that pathway is targeted by a drug/chemical. For example, α4-integrin homozygous knockout mice are embryonic lethal, with embryo lethality demonstrated at different times during development (Yang et al., 1995), whereas heterozygotes are viable and normal through at least 1 year of age. Based on this information, it was postulated that α4-integrin inhibitors had the potential to produce developmental toxicity, and that toxicity could depend on the extent and duration of inhibition. This prediction was found to be true when three different inhibitors were tested in rabbits (Crofts et al., 2004). There was variability in the response to these compounds which correlated with the degree of inhibition, and the observed malformations were consistent with the predicted effects observed in the knockout mice.

Understanding interspecies differences in the expression of these targets is also important for designing appropriate testing strategies, including species selection. An example was provided where a receptor targeted by a drug candidate was expressed in rabbits, but not rats. In this case, fertility and embryo–fetal development studies, which are routinely conducted in rats, were conducted in rabbits as the pharmacologically relevant species. However, the potential for off-target toxicities must be considered in animal testing. For this reason, this compound was also tested for embryo–fetal developmental toxicity in rats to determine potential for effects unrelated to target pharmacologic effect.

Interspecies differences in metabolism can lead to differences in developmental toxicity. Understanding metabolic pathways in test species and humans is important to designing and interpreting animal studies and their potential relevance to humans. Interspecies differences in embryonic development and the extra-embryonic environment can also lead to species discordance in developmental toxicity. For example, toxic effects on the visceral yolk sac can lead to malformations in rodents that would likely be of reduced concern for humans as their reliance on histiotrophic nutrition (yolk sac) is minimal. The importance of toxicokinetics in study design and interpretation was emphasized, including species selection, dosing regimen, and extrapolation of data to humans (i.e., relative exposure, safety margins). For example, for pharmaceuticals it is generally preferable to use the same route of administration in animal studies as will be prescribed for humans. However, some routes of administration are not amenable for study in animals (e.g., intranasal administration) and can introduce significant confounds. In these cases, alternative routes of exposure may be used (e.g., IV), as long as the dosing regimen provides an exposure profile representative of that expected in humans. Characterization of pharmacokinetics (PK) by various routes will allow design of a dosing regimen that will produce comparable exposures and provide appropriate coverage of gestation.

Presentation 2: Comparative Embryology and Interspecies Concordance. Presented by: Dr. John DeSesso, Exponent

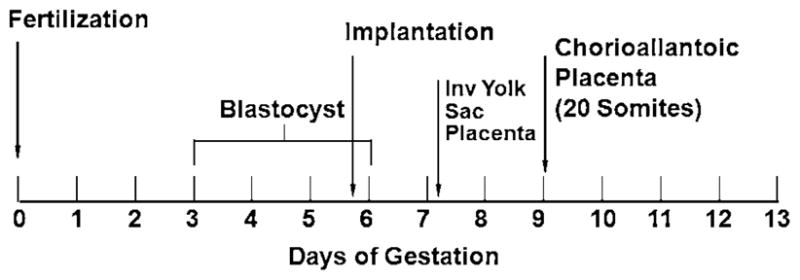

The objective of this presentation was to provide an overview of embryonic development across species, including key embryo/fetal milestones (Table 1) and timing (Fig. 1), and considerations related to developmental toxicity study design and interpretation. Particular attention was paid to species differences in placentation and embryo/fetal nutrition. Many experimental animals, including the rat and rabbit, possess an inverted visceral yolk sac placenta that is established earlier than the chorioallantoic placenta, transports materials by a different mechanism, and remains functional until term. These differences may be critical in understanding potential interspecies differences in drug/chemical transport to the fetus, and mechanisms of teratogenesis. Dr. DeSesso also briefly discussed the concept of “pathway-based” developmental toxicity screening. It is clear that there are highly conserved, developmentally important molecular signaling pathways which are used repeatedly throughout organogenesis, such as the 17 pathways discussed in the National Academy of Sciences Report (Committee on Developmental Toxicology, Board on Environmental Studies and Toxicology, National Research Council, 2000). These may represent convergent mechanistic pathways for developmental toxicity. Thus, identification and characterization of a finite set of developmentally critical molecular targets could allow for design of simpler model systems for developmental toxicity screening. However, it must be emphasized that embryonic development involves both key molecular signaling mechanisms and complex coordination/integration of biological systems. Predictive safety tests must integrate procedures that successfully assess both. Further, redundancy, homeostasis, and capacity for repair also contribute to ultimate developmental outcome and must be considered in defining alternative testing schemes.

Table 1.

Gestational Milestonesa for Mammals

| Species | Implantation | Primitive streak | Early differentiation | Organogenesis ends | Usual parturition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rat | 5–6 | 8.5 | 10 | 15 | 21–22 |

| Mouse | 5 | 6.5 | 9 | 15 | 19–20 |

| Rabbit | 7.5 | 7.25 | 9 | 18 | 30–32 |

| Hamster | 4.5–5 | 7 | 8 | 13 | 16 |

| Guinea Pig | 6 | 12 | 14.5 | ~29 | 67–68 |

| Monkey | 9 | 17 | 21 | ~44–45 | 166 |

| Human | 6–7 | 13 | 21 | ~50–56 | 266 |

In gestational days; day of confirmed mating = gestational day 0. (Reproduced with permission from DeSesso, J. M., (2006) “Comparative Features of Vertebrate Embryology,” Chapter 6 in Developmental and Reproductive Toxicology: A Practical Approach, 2nd Ed., R. D. Hood, Ed., CRC Press, Inc., Boca Raton, FL, p 147–197.)

Fig. 1.

Chronology of early events during gestation of mouse embryos.

(Reproduced with permission from DeSesso, JM (2009). Comparative embryology and interspecies concordance. Presented at the HESI Developmental Toxicology—New Directions Workshop, Washington, DC, April 29.)

Presentation 3: Pharmacokinetic Considerations and Species Selection: A case of the PFAAs. Presented by: Dr. Christopher Lau, US EPA

The developmental toxicity profile of the PFAAs was presented as a further example of how pharmacokinetic data for a compound of interest can greatly inform the testing scheme. In this case, identification of interspecies and gender differences in half-life contributed to species selection and design of an appropriate dosing regimen for the testing of PFAAs. PFAAs are widely used industrial chemicals which have been found in human serum (National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data) and in wildlife (fish, birds & even polar bear) and tend to be exceedingly persistent, with half-life estimates ranging from 2 days to 9 years in humans. Some PFAAs have potential for hepatotoxicity, carcinogenicity, developmental toxicity, and immunotoxicity, based on animal studies. In general, prenatal evaluations of PFAAs in laboratory animal models have revealed only minimal structural abnormalities and developmental delays at high doses, with no significant alteration in implantation or fetal viability at term. However, in the rodent models, dramatic effects on neonatal survival following maternal exposures have been observed, which are variable among compounds. Perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) produced dose dependent neonatal mortality in both mice and rats in a similar dose range. On the other hand, the fully fluorinated carboxylate, perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) produced similar effects on neonatal survival in mice, but only slight postnatal growth deficits with no neonatal mortality occurred in rats. This difference was primarily attributed to rapid clearance of PFOA in female rats (t1/2 of 2–4 hr compared to 6–7 days in male rats, and 16–22 days in female and male mice). In contrast, no gender or interspecies difference in clearance was identified for PFOS (Lou et al., 2009), which corresponded to the similarity of response between these two rodent species. In humans, t1/2 for PFOA is estimated at 2.3 to 3.8 years, with no significant gender difference reported. Based on these findings, the mouse is therefore considered to be a more appropriate model than the rat for testing of PFAA reproductive and developmental toxicity. Characterization of PK in various species in advance of testing would identify potential interspecies differences that could impact hazard identification and risk assessment, and optimize species selection and dosing regimen.

Presentation 4: Mode of Action Studies: Using knockout mice to study the developmental toxicity of PFOA and PFOS. Presented by: Dr. Barbara Abbott, US EPA

PFOA and PFOS are both C8 perfluorinated compounds that may act through a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-mediated mode of action. In tests for PPAR activation, the doses of these chemicals required for action are very different. Using transfected cells, a comparison of the perfluorinated compounds of varying carbon lengths showed that activation of PPARα, (the putative mode of action for some reported health effects in rats and mice) was dependent on chain length and type of end group (sulfonate or carboxylate) (Abbott et al., 2009; Takacs and Abbott, 2007). PFOA and PFOS were tested in both wild type and PPARα knockout mice. PFOA induced neonatal lethality in wild type, but not knockout mice (Fig. 2), confirming that this effect was induced through a PPARα mode of action. In contrast, neonatal lethality induced by PFOS was not dependent on expression of PPARα. This study indicated that even closely related chemicals could act differentially in producing developmental toxicity, and some of these modes of action could be teased out by using specially developed strains of animals.

Fig. 2.

The postnatal survival of pups is shown as the percent of the litter alive on PND1 to 10, 14, 17, and 22 for WT (A) and PPARa KO (B) strains. A significant decrease (p < 0.001) compared to control occurred only in the WT litters of dams exposed to 0.6 or 1 mg/kg on GD1 to 17. Data shown are the mean of litter means for 10, 9, 6, 7, and 10 WT and 7, 11, 9, 8, and 16 KO litters, in the order listed in the legends, respectively.

(Reproduced with permission from Abbott BD, et al. 2007. Perfluorooctanoic acid-induced developmental toxicity in the mouse is dependent on expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha. Toxicol Sci 98:571–581.)

Presentation 5: Reproductive toxicity testing strategies for biologics. Presented by: Dr. Mary Ellen McNerney, Bristol-Myers Squibb

An overview of the current state of the art in reproductive toxicity testing of new biopharmaceuticals was presented. Owing to the nature of their targets and the species and tissue specificity of biological pharmaceutical agents, conducting relevant and informative safety assessments of new biopharmaceuticals can be complicated. The greatest challenge in this area is selecting appropriate test species. An addendum to the ICH guideline S6 (1997) (Preclinical Safety Evaluation of Biotechnology-Derived Pharmaceuticals) has been drafted. Among other changes, this addendum clarifies and enhances the guidance regarding DART testing for biopharmaceuticals. Biopharmaceuticals specifically designed to target human proteins (e.g., monoclonal antibodies) are often not active in common laboratory species and/or may be immunogenic. Presently, the recommendation is to use cynomolgus monkeys for agents that are not biologically active in rodents or rabbits. This recommendation is based on the assumption that the agent would not evoke neutralizing antibodies in this type of primate and on the hypothesis that outcomes in the nonhuman primate (NHP) study could be readily extrapolated to humans. NHP reproductive toxicology studies are not without significant drawbacks, however. Many reproductive and developmental endpoints involve low incidence observations, and in order to have adequate statistical power to detect these kinds of changes, group sizes may need to be large. NHP studies tend to have small group sizes, and their results are consequently often difficult to interpret. Furthermore, the combination of the required timing for DART testing relative to clinical development, a limited number of laboratories worldwide capable of conducting the necessary NHP studies, and the amount of prior planning necessary to conduct a study in pregnant monkeys means that a NHP study for a biopharmaceutical must be scheduled and initiated at significant risk. Specifically, commitment to such a study would have to be made approximately 30 to 39 months before initiation of the clinical trial which it will support.

Because NHP studies are notoriously difficult to interpret, the ethics of using the animals in this way and the wisdom of investing the required resources (multiple millions USD) may be questionable in some cases. It may, therefore, be prudent to consider alternatives in small animal models in which a traditionally powered, ICH (2005) S5R2-recommended study design is feasible. Alternatives fall into one of the following categories.

Transgenic rodents: The effects of loss of the therapeutic target can be tested with a knockout mouse model in a traditional study design with typical group sizes, but concern exists that these models may not accurately predict the effects of the candidate on pregnancy due to target redundancy or embryo lethality. Similarly, the clinical candidate can be administered to knock-in or humanized rodents, but these may lack interacting proteins or pathways and important regulatory sequences. Furthermore, the clinical candidate may be immunogenic in the rodent. In either case, the time required to develop and/or validate the model may be significant.

Rodent homologous proteins: A protein that is functionally and structurally analogous to the clinical candidate and recognizes the homologous therapeutic target in the rodent may be a viable alternative to testing of the candidate molecule. However, differences in production and formulation from the clinical candidate may introduce confounding variables, and this approach essentially requires development of a second, parallel drug.

Tool molecules: Even a structurally dissimilar tool molecule may be used to evaluate on-target effects if functional similarity in the test species is established.

In comparing NHP studies and the various alternative options, it was clear that each choice is resource-intensive and requires very early planning. In the end, it is most important to decide which choice will provide the best risk assessment for humans. Currently, alternative strategies are considered when the clinical candidate is active only in humans and NHPs, but there are encouraging signs that US regulatory agencies will be accepting of well-planned, rational study designs with alternative models.

DISCUSSION

The discussion centered on topics that can generally be grouped into two broad categories:

Refining current animal testing strategies: This includes points related to use of toxicokinetic data, dose selection, possible tiered/triggered testing strategies, species selection, and use of alternative animal models.

Considerations for non-animal-based testing paradigms, including: defining a “signal,” translating in vitro exposures to whole animal and human exposures, validation strategies, the need for a bridge/education between classical toxicology testing and risk assessment, and development of new technologies.

The main discussion points within each of these areas are summarized below.

A recurring theme that resonated throughout the discussion was the differences between testing strategies and risk assessment for pharmaceuticals and chemicals. Although developmental toxicity studies are similar between pharmaceuticals and chemicals, the use of the data in risk assessment is very different. Therefore, prioritization of issues related to refinement and optimization of study design and interpretation may also be very different. For example, pharmaceuticals are generally considered to have potentially high benefit in a limited population whose exposures are tightly controlled and voluntary. In contrast, exposures to industrial and agricultural chemicals in the environment tend to occur at much lower levels, but they can occur unknowingly and may have greater potential population exposure. Therefore, “acceptance” of risk is very different. Further, there is often a wealth of information available for pharmaceutical candidates at the time developmental toxicity testing is conducted, including characterization of pharmacologic activity, toxicokinetics and metabolic profile in multiple species (including human), and anticipated human exposure levels, which can guide study design and interpretation. Chemicals are generally not designed for specific biological activity in mammalian systems, and therefore, biological effects are more difficult to anticipate. Toxicokinetic evaluation in animal studies has not been typical in chemical testing, although this is starting to change.

1. Refining current animal testing strategies

a. Use of toxicokinetic data

There was a great deal of discussion about the value of toxicokinetic data to support study design, interpretation, and risk assessment, including species selection, dose selection and dosing regimen, and defining safety margins.

Major pharmacokinetic and metabolic differences can exist between species, and between genders. Characterization of these differences and understanding of the biological processes that underlie them will facilitate the cross-species extrapolation in human health risk assessment. In the example of the PFAAs provided by Dr. Lau, differences in the developmental toxicity profiles between species and among compounds could be attributed to species and sex differences in disposition and elimination. Based on available human data, the rat is probably not the most appropriate test species, particularly for PFOA, based on its rapid elimination in female rats relative to humans.

Other examples provided by Dr. White highlighted the importance of PK in dose and route selection. This was illustrated in the example of a drug intended for intranasal administration in humans, which was not feasible in developmental toxicity studies. An acceptable intravenous dosing regimen was defined to provide a pharmacokinetic profile similar to that achieved in humans.

There was general consensus that characterization of toxicokinetic and metabolic profiles in multiple species, including humans, in advance of developmental toxicity testing could improve study design, interpretation, and relevance for human risk assessment. However, the added value of these efforts must be weighed against the added time and resource expenditure required to develop analytical methods and to conduct pharmacokinetic studies in multiple species. This was particularly emphasized for testing of chemicals where such pharmacokinetic information is generally not routinely collected. For chemicals, toxicokinetics are generally characterized only as part of follow-on investigations when findings/issues are identified. A clear benefit to collecting this information routinely and earlier in a program would have to be recognized before it would be adopted by industry.

There was brief discussion on study design considerations for collection of toxicokinetic information, including timing (how often and when during gestation) and the value of collecting both fetal and maternal exposures. Maternal exposures provide information relevant to human exposure. Fetal exposures provide information regarding the distribution of the test compound to the tissue of interest (the conceptus). Fetal exposure (and metabolism) may be very different from that of the dam and thus cannot be predicted from determining dam exposure only. However, relevant human fetal data for interspecies comparison would rarely, if ever, be available. When fetal exposures are determined in developmental toxicity studies, it is generally conducted only late in gestation, when fetal blood can be obtained. However, the relevance of exposure at this time to earlier developmental stages may be unclear. As discussed previously, the value of collecting fetal exposure data at multiple developmental stages must be weighed against resource expenditure (e.g., would require development of tissue analytical methods). The purpose of collecting this information should be carefully considered with regard to understanding human risk.

There was some discussion on the value of PK from nonpregnant animals in designing developmental toxicity studies. Physiological changes during pregnancy can lead to significant differences in compound distribution and disposition. Therefore, although these data might have general utility in species and dose selection, caution must be taken in applying data from nonpregnant to pregnant animals.

The placenta is another important consideration in developmental toxicity testing. Physicochemical properties and structure of a compound can provide some clues regarding a compound’s potential to cross the placenta. However, species differences in placental structure and function can lead to differences in placental transport and fetal exposure. Placental transfer may also change during gestation as placental structure and function matures. As discussed by Dr. White and Dr. DeSesso, the yolk sac and placenta can also be a target for toxicity, impacting fetal nutrition and developmental outcome. Such effects in laboratory species may be of limited relevance for humans based on differences in the importance of visceral yolk sac.

Lactational transfer should be taken into consideration in pharmacokinetic modeling for those studies that evaluate postnatal end points.

b. Dose selection

There were comments throughout the discussion about the need to move away from high, maternally toxic doses that may be meaningless for human exposure. Rational dose selection was considered to be one way to refine developmental toxicity testing and improve the relevance of these studies for human risk assessment. Currently, dose selection for developmental toxicity studies is usually driven by the need to demonstrate some maternal toxicity (e.g., adverse clinical signs, deficits in body weight gain and/or food consumption) at the high dose. Although there is an acceptable limit dose of 1 g/kg/day included in testing guidelines for both EPA and ICH, this dose would often represent exposure that is orders of magnitude beyond anticipated human exposure. For carcinogenicity testing of pharmaceuticals, a high dose of 25-times human exposure based on area under the curve is acceptable when a maximally tolerated dose has not been demonstrated (ICH, S1C(R2) Dose Selection for Carcinogenicity Studies, 2008), but such an approach has not been adopted for developmental toxicity testing. For industrial chemicals, an alternative approach gaining some traction is the setting of the high dose level based on toxicokinetics, specifically to avoid dose levels which saturate metabolic and excretory processes and result in nonlinear kinetics. This approach is appropriate for chemicals which are present at low levels in the environment, such that the kinetic profile in the animal studies is relevant to that of low level exposure. It was the consensus of the majority of attendees that a more rational upper limit should be adopted.

The use of maternal toxicity to drive dose selection for developmental toxicity testing has been justified as a means to improve the sensitivity of these studies, by increasing the probability that treatment-related effects will be detected. However, this approach assumes that events that occur at high doses are relevant to low doses, and does not account for potential dose-dependent mechanisms. For example, a pharmaceutical agent that has very high selectivity for the targeted pharmacologic effects at therapeutically relevant doses may have secondary effects at high doses that could lead to toxicities not relevant to therapeutic use. The same would be true for chemical exposure. Identification of developmental toxicity at high doses often leads to follow-up investigational studies to define mechanism and provide perspective for human assessment, requiring extensive time and resources. The understanding of dose-dependent mechanisms will become increasingly important in considering alternatives to animal testing and understanding exposure–toxicity relationships in mechanistic pathway-based approaches (see below).

The impact of maternal toxicity on developmental outcome and interpretation of toxicity findings is also an important consideration in study design, dose selection, and interpretation. This topic was not discussed in detail in this session but has been revisited in a series of recent workshops sponsored by the Health and Environmental Sciences Institute (HESI) DART Technical Committee (Beyer et al., 2011).

c. Number and choice of test species

Many participants felt that, with more data and an increased understanding of mechanisms, it would be possible to move away from the default scheme of testing one rodent and one nonrodent species. This would allow us to move toward more tailored, rational testing programs. One potential modification would be testing in only one species when the available science supports that decision. An example could include testing only in rabbits if the target receptor is expressed only in rabbits, although as previously emphasized, nontarget toxicity must be considered and testing in a second species may be important to identify such effects. As previously mentioned, biopharmaceuticals are typically only tested in a single “pharmacologically relevant” species. In some cases, a particular species may produce data of limited or no use based on sensitivity. For example, anti-infectives tend to eliminate gastrointestinal microflora, resulting in severe gastrointestinal disturbances in rabbits that can significantly confound the study results. In this case, testing only in rats is generally acceptable (i.e., testing in a second alternative species to rabbits is usually not required). These examples show that, when scientifically justified, alternatives to the default scheme of testing in two species are acceptable.

d. Endpoints

There was little discussion on the refinement of current studies with regard to specific endpoints. The participants acknowledged that removing endpoints that have not proven informative or useful in developmental toxicity testing and risk assessment could streamline testing and potentially save resources. However, defining “value” of particular endpoints is a formidable challenge and in general was not considered to be a fruitful discussion for this workshop. There were, however, a few points worth noting.

There have been many efforts to evaluate specific developmental findings with regard to relevance for developmental toxicity and human risk assessment (e.g., defining adversity, reversibility, relationships to growth and fetal body weight, impact of maternal toxicity). For example, interpretation of skeletal variations has been an area of particular focus. Another example would be the importance of findings that are anatomically relevant only to the test species but not to humans (e.g., tail malformations in rodents). Should interpretation of observations and risk assessment be based on the specific findings observed, their perceived adversity, and relevance to humans? Or should any findings be considered indicative of potential for a test article to disrupt development? In other words, what defines a “signal” of potential concern for human developmental toxicity? These are questions that have long been, and continue to be, highly debated. For many common findings in standard developmental toxicity studies, there is general consensus on interpretation and level of associated concern. However, as we consider non-animal testing strategies, where the relevance of endpoints for understanding toxicity and importance for human development are even less clear, these questions will become even more important.

e. Tiered/triggered testing strategies

Overall many of the participants seemed to agree that the current testing paradigm is working pretty well and there is a high level of confidence in the interpretation of these studies. However, because it is very time-consuming and labor intensive, very few compounds can be studied using this paradigm. Therefore, the concept of tiered or triggered testing approaches was met with some enthusiasm, although there was no discussion on which tests should be included in a tiered approach, and what findings would trigger the need for a higher level test. This was identified as an area that would merit further discussion.

Agricultural Chemical Safety Assessment (ACSA) Technical Committee of International Life Sciences Institute (ILSI) and Health and Environmental Sciences Institute (HESI) recently proposed a tiered approach to life stages testing for agricultural chemicals. Life stages included preconception, development, adolescence, and adults. Specific reproductive/developmental toxicity are among tests in Tier I and include a prenatal developmental study in the rabbit and a novel F1-extended one-generation reproductive study in the rat (Cooper et al., 2006). Tests in Tier 2 could include a prenatal developmental toxicity study in a second species, a multigeneration reproduction study in rats and additional studies of mode of action, absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion or additional endpoints (neurotoxicity, immunotoxicity, endocrine). Although several possible triggers for Tier 2 testing are indicated in the document from the workshop (Cooper et al., 2006), scientific judgment would determine which, if any, of the Tier 2 tests would need to be done.

Alternative developmental toxicity tests (e.g., in vitro assays, alternative species) are commonly used within industry to screen and prioritize candidate compounds, and could potentially be used by regulatory agencies to similarly set priorities for further testing. However, greater confidence in the interpretation of these studies, both in the relevance of positive findings (i.e., potential for false positives) and confidence in lack of findings (i.e., potential for false negatives), is needed before adopting these assays for regulatory decision-making. A more detailed discussion of considerations in the utilization of alternative assays is presented below.

f. Use of alternative animal models

i. Transgenic and knockout rodents

The contribution of genetically modified animal models (e.g., transgenics, knockout) to our understanding of the role of specific genes and pathways in development and disease is clear. The value of these models in the understanding of mode-of-action for toxicity has also been demonstrated. Dr. Abbott provided a clear example of how knockout mice can be used to investigate and identify developmental toxicity mode-of-action. In her studies, PPARα knockout mice were used to determine the importance of PPARα activation in the developmental toxicity of PFOA and PFOS.

Dr. White also discussed the value of genetic models to provide an early indication of potential developmental toxicity for pharmaceuticals. Knockout or knockdown models can provide information about the importance of a pharmacologic target in development, and thus potential concern for developmental toxicity of pharmaceuticals, such as the example of α4-integrin inhibitors presented above. This information can be used to prioritize developmental toxicity testing within a program, and guide study design, as well as endpoints (e.g., special evaluations based on developmental outcomes in genetic models), and species selection (e.g., ensuring pharmacologic activity of the pharmaceutical in the test species).

Although the participants recognized the contribution of these models to understanding developmental toxicity, there was consensus that these models do not really have a role in standard testing paradigms. The value of these models is as described above; they can provide an early indication of potential concern, and can be used in follow-on studies to identify mode-of-action.

ii. Disease models—susceptible populations

An important challenge in toxicity testing is identification of, and understanding risk to susceptible populations. In the case of pharmaceuticals, drugs are intended to modulate or “normalize” disease states in patient populations, whereas toxicity testing is conducted in healthy animals, where administration of drugs may in fact lead to an abnormal physiological state. One example is diabetes, where treatment leads to normalization of blood sugar in patients, but hypoglycemia, which has been associated with adverse developmental outcome, may be induced in normal animals treated with antidiabetic compounds. There was brief discussion of the potential value of developmental toxicity testing in disease models to more closely mimic the human situation. Although the participants acknowledged the concern and felt this topic warranted further consideration, the consensus was that routine testing in disease models was not a good idea. How well animal disease models recapitulate the human condition is often unclear. The lack of historical experience and data for developmental outcomes in disease models is problematic for their use in routine testing. In many cases the disease state itself may be associated with adverse developmental outcome; additionally reproductive success in these models may be low, further complicating testing in these models and interpretation of results. It is also important to bear in mind that for pharmaceuticals, toxicity does not always equal pharmacology. As pointed out in Dr. White’s presentation, developmental toxicity may be mediated through off-target activity; it is important to not focus only on toxicity associated with the target pharmacology.

2. Considerations for non-animal-based testing paradigms

There was a great deal of discussion around considerations for alternatives to current testing paradigms for developmental toxicity. Alternative tests are usually considered to be in vitro or in silico models, although the definition of alternative tests could be expanded to include nonmammalian animal models (frogs, zebrafish, C. elegans, Drosophila). In vitro models for developmental toxicants include the rodent whole embryo culture test or the embryonic stem cell test. However other in vitro assays that can define physiological effects of compounds can provide supplemental information that could be helpful in designing the best test. For example, Dr. White provided an example of a biological compound that can cross the visceral yolk sac in rodents by binding to a particular receptor. An in vitro test in which rat cells express this receptor on their cell surface could be used to examine binding potential of several similar compounds as well as to determine binding of the compound to a mutated receptor. In silico models can be used to predict developmental toxicity based on structure–activity relationships or bioactivity profiles (e.g., ToxCast, EPA’s program to use high-throughput assays to predict potential toxicity and prioritize testing of a large number of chemicals for toxicity testing; Dix et al., 2007).

Critical to this discussion is the need to define the drivers for using alternatives to whole animals because these will lead to very different considerations/concerns. For example:

-

Use in screening/prioritization versus definitive testing. If the alternative approach is intended as an initial screen whose results will be used to set priorities for additional, definitive testing, considerations will be very different than if the test is intended to provide definitive results to support regulatory decision-making. In the former, false-positive and false-negative results would be of lesser concern than in the latter, as additional data will become available for confirmation. The need for appropriate validation of assays and endpoints will also be driven by these objectives.

Programs such as Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemical substances, Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development, Screening Information Data Set, and Environmental Protection Agency, High Production Volume Challenge program have driven the need to provide toxicology data for large numbers of previously poorly characterized chemicals. Testing of these chemicals using current animal testing paradigms is not feasible based on resources as well as animal and time requirements. Therefore, there is a need to provide reliable screening methods to provide data to fill critical gaps and/or to set priorities for definitive testing.

Risk/benefit considerations for pharmaceuticals versus environmental chemicals. As previously noted, pharmaceuticals are generally considered of high benefit with limited exposure. Therefore, the potential for false positives that could lead to termination of a beneficial therapy will be of high concern. On the other hand, because of potential broad population exposure, false negatives are of high concern for environmental chemicals due to possible underestimation of risk.

Two general topics emerged as areas of high concern for the participants in considering alternatives to whole animal testing: (1) defining a “signal”; (2) extrapolation of dose to “exposure.”

a. Defining a “signal”/adversity

In our current animal testing paradigm, there is a high level of confidence regarding what would be considered “adverse” findings (death, growth retardation, malformations) although, as noted previously, the relevance of some findings for human risk assessment is still debated. As we move to alternative models, including nonmammalian species (e.g., zebrafish), cell-based systems, mechanism/pathway-based screening or even in silico models, outcomes that define a toxicity signal are less certain. How would we differentiate biological versus toxicological response? Is any activity of concern?

Developmental toxicity presents a unique challenge in that the developmental outcome is dependent on the complex interactions between the dam, placental and fetal units. These interactions are reflected in our current whole animal testing paradigms. How do we capture the complexity of these interactions and their impact on development in a cell-based, mechanism-based, or in silico assay? It may be necessary to use multiple alternative tests, as no one test appears to correctly identify all developmental toxicants tested. Similarly, how do we account for homeostasis, repair, and/or recovery following initial insult?

As noted above, the impact of these questions depends on the objective for these studies. If the driver for these studies is initial screening and prioritization for follow-up testing, then these considerations are somewhat less important. A biological response in these systems would trigger further study for confirmation. However, if the assay is intended as a definitive test that will drive regulatory decisions, then defining what constitutes an adverse outcome and appropriate interpretation of findings becomes critical. For example, it was noted that in vitro tests are mandated as part of the REACH program. Because of social and political pressures to prevent an increase in animal testing as part of this program, in vitro studies cannot be followed up by in vivo testing without permission from EU authorities. Thus a positive signal in an in vitro assay could lead to regulatory action such as a ban or severe restrictions on a chemical. Therefore, it is absolutely critical that endpoints are defined and interpretation is appropriate.

Inherent in these questions is the issue of validation, which was raised throughout the discussion. Although validation approaches were not discussed in detail, the participants agreed that appropriate validation was critical for these alternative assays. The validation process is lengthy and difficult, as evidenced by the recent validation of the embryonic stem cell test by European Centre for the Validation of Alternative Methods (ECVAM). It is even difficult to get experts to agree on which chemicals should be used in a validation process. Additionally, it was noted that validation of new technologies is often led by those that developed them, which could introduce bias and potentially presents a conflict of interest. Validation needs to be independent, objective, and unbiased.

b. Exposure perspective

Translating in vitro concentrations to whole animal and human exposure.

The second issue that was discussed extensively was the issue of how to select concentrations for testing in alternative assays and interpretation of these concentrations relative to human exposure.

For pharmaceuticals, potency of the drug at the pharmacologic target is usually known, and pharmacologic activity in binding assays and/or cell-based assays is generally well characterized. Binding at off-target sites and relative potency at these sites is also often characterized through in vitro screening, which can provide information about potential secondary effects. Therefore, in these cases, interpretation of effects observed in alternative in vitro assays can be interpreted relative to expected pharmacologic activity. Further, as has been discussed previously, anticipated human blood levels are generally known for pharmaceuticals, which can also provide context for interpretation of in vitro results. However, such information is generally not available for chemicals, so interpretation of in vitro results for human health risk assessment is more problematic.

Further, many factors determine target tissue concentration, including metabolism (maternal, placental and fetal), protein binding, and transport of compounds across the placenta. Maternal blood levels may not accurately reflect local embryonic concentrations. Many factors also impact target tissue response to exposure, including homeostasis and repair, which may not be captured in in vitro or nonmammalian systems. These factors must be carefully considered in the design and interpretation of these studies.

CONCLUSIONS

The current paradigm for developmental toxicity testing is basically a screen. But it is a screen that has served us fairly well over the last 40 years. There is a high level of confidence in the conduct and interpretation of these studies although refinements such as broader incorporation of toxicokinetics, dose and species selection could potentially strengthen these studies for human risk assessment.

However, there are pressures to change this screen. Some of this pressure is from individuals who would like to see fewer animals used in research. There is pressure on regulatory agencies to make decisions regarding human exposure to compounds for which there is little/no developmental toxicity data, and the time and cost involved in obtaining such data are prohibitive. There is financial pressure for companies that want to market products that are efficacious and safe. A desire was expressed by many of the participants to move away from regulatory “box-checking” and toward more hypothesis-driven study designs and strategies.

Advances in our understanding of embryology, molecular and developmental biology, and mechanisms of teratogenesis, as well as in vitro, molecular and in silico technologies provide tremendous opportunity to investigate the effects of compounds on development in new ways. However, because many of these tools were not developed specifically for the study of toxicologic effects, the appropriate application of these approaches to hazard identification/characterization and human health risk assessment will require collaboration and a common understanding among whole animal toxicologists, molecular biologists, bioinformaticists, and regulatory decision makers.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Tacey White (GSK), John DeSesso (Exponent), Christopher Lau (EPA), Barbara Abbott (EPA), and Mary Ellen McNerney (BMS) for their presentations at the Developmental Tox—New Directions Workshop and for their contributions to this publication.

Footnotes

The views expressed in this manuscript represent the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of their employers.

References

- Abbott BD, Wolf CJ, Das KP, et al. Developmental toxicity of perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) is not dependent on expression of peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-alpha (PPAR alpha) in the mouse. Reprod Toxicol. 2009;27:258–265. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2008.05.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer BK, Chernoff N, Danielsson BR, et al. ILSI/HESI maternal toxicity workshop summary: maternal toxicity and its impact on study design and data interpretation. Birth Def Res B. 2011;92:36–51. doi: 10.1002/bdrb.20281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Developmental Toxicology, Board on Environmental Studies and Toxicology, National Research Council. Scientific frontiers in developmental toxicology and risk assessment. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper RL, Lamb JC, Barlow SM, et al. A tiered approach to life stages testing for agricultural chemical safety assessment. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2006;36:69–98. doi: 10.1080/10408440500541367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crofts F, Pino M, DeLise B, et al. Different embryo-fetal toxicity effects for three VLA-4 antagonists. Birth Def Res. 2004;71:55–68. doi: 10.1002/bdrb.20001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dix DJ, Houck KA, Martin M, et al. The ToxCast program for prioritizing toxicity testing of environmental chemicals. Toxicol Sci. 2007;95:5–12. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfl103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ICH Harmonized Tripartite Guideline. Preclinical safety evaluation of biotechnology-derived pharmaceuticals. 1997:S6. doi: 10.1038/nrd822. Available at: http://private.ich.org/LOB/media/MEDIA503.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- ICH Harmonized Tripartite Guideline. Detection of toxicity to reproduction for medicinal products and toxicity to male fertility. 2005;(R2):S5. Available at: http://private.ich.org/LOB/media/MEDIA498.pdf.

- ICH Harmonized Tripartite Guideline. Dose selection for carcinogenicity studies of pharmaceuticals. 2008;S1C(R2) Available at: http://private.ich.org/LOB/media/MEDIA491.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- ICH Harmonized Tripartite Guideline. Addendum to ICH S6: Preclinical safety evaluation of biotechnology-derived pharmaceuticals. 2009;S6(R1) Available at: http://private.ich.org/LOB/media/MEDIA5784.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Lou I, Wambaugh JF, Lau C, et al. Modeling single and repeated dose pharmacokinetics of PFOA in mice. Toxicol Sci. 2009;107:331–341. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takacs ML, Abbott BD. Activation of mouse and human peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (alpha, beta/delta, gamma) by perfluorooctanoic acid and perfluorooctane sulfonate. Toxicol Sci. 2007;95:108–117. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfl135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang JT, Rayburn H, Hynes RO. Cell adhesion events mediated by alpha 4 integrins are essential in placental and cardiac development. Development. 1995;121:549–560. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.2.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]