Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this article was to summarize scientific knowledge from an expert panel on reproductive health among adolescents with type 2 diabetes (T2D).

Methods

Using a mental model approach, a panel of experts—representing perspectives on diabetes, adolescents, preconception counseling, and reproductive health—was convened to discuss reproductive health issues for female adolescents with T2D.

Results

Several critical issues emerged. Compared with adolescents with type 1 diabetes, (1) adolescents with T2D may perceive their disease as less severe and have less experience managing it, putting them at risk for complications; (2) T2D is more prevalent among African Americans, who may be less trusting of the medical establishment; (3) T2D is associated with obesity, and it is often difficult to change one’s lifestyle within family environments practicing sedentary and dietary behaviors leading to obesity; (4) teens with T2D could be more fertile, because obesity is related to earlier puberty; (5) although obese teens with T2D have a higher risk of polycystic ovary syndrome, which is associated with infertility, treatment with metformin can increase fertility; and (6) women with type 2 diabetes are routinely transferred to insulin before or during pregnancy to allow more intensive management.

Conclusions

Findings from the expert panel provide compelling reasons to provide early, developmentally appropriate, culturally sensitive preconception counseling for teens with T2D.

This article reports the findings of an expert panel convened to review what is known about adolescents with type 2 diabetes (T2D) in relation to reproductive health, pregnancy risks, and preconception counseling. It is the first step in a larger project, which uses the mental models approach to develop effective risk communication tools.1 This approach begins with the creation of a formal model, identifying key variables and positing how they are related. Later steps use this model to assess risk communication (information) needs in the target audience (in this case, adolescent girls) and guide the development of appropriate communication tools (in this case, an interactive DVD). This article reports on the initial step of the process, the literature search, and expert panel consultation behind the development of an expert model of diabetes, reproductive health, and preconception counseling for adolescents.

Glycemic control can affect reproductive health in both women with type 1 diabetes (T1D) and women with T2D.2 Starting with puberty, uncontrolled diabetes can also have a major impact on sexual function,3 pregnancy-related complications, and morbidity and mortality in the offspring.4–7 Most of these problems can be prevented with tight glycemic control, which can be fostered by planning a pregnancy through preconception counseling.4,5,8,9 However, more than two-thirds of all pregnancies in women with diabetes are unplanned, heightening their risks for complications.4,7,10,11 The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends preconception counseling for all women with diabetes of childbearing potential, starting at puberty.12 Preconception counseling, however, tends to be offered to women who are imminently planning a pregnancy13,14 and rarely started as early as adolescence, a time prior to sexual activity, when unplanned pregnancies can truly be avoided and wanted pregnancies sufficiently planned in advance to meet the ADA goals.15 Therefore, most adolescent girls with diabetes are unaware of their increased risk of pregnancy complications or the power of tight metabolic control in preventing complications both prior to and during pregnancy.16

Although much is known about reproductive health issues in adolescents with T1D,16–19 these issues are not yet well described in adolescents with T2D. T2D now accounts for up to 45% of new-onset diabetes cases among adolescents worldwide and continues to rise.20–22 The prevalence is especially high among some minority populations, including Native Americans and Americans of African, Hispanic, and Asian descent,21,23 populations that together are growing faster than the US population as a whole due to migration and birth rates.24

The few existing preconception counseling efforts aimed at adolescents have mostly focused on T1D.17 Because adolescents with T2D may have unique needs for preconception counseling and reproductive health, this panel sought to summarize relevant expertise into a single, coherent model of existing knowledge using the mental models approach described below. To that end, a literature search was conducted on this topic of women with T1D and compiled key concepts, and then a panel of experts was convened representing multiple perspectives, including adolescent health, T2D, preconception counseling, cultural issues, and pregnancy risks to complete the model.

Methods

Mental Models Approach

This article aims to consolidate the existing literature and the input from the expert panel by using a mental models approach to summarizing scientific knowledge.1 This approach is especially useful in cases such as reproductive health risks in diabetes, when relevant expertise spans a variety of disciplines.25 Members of this research team have previously developed expert models to describe sexual behavior risks26–29 but have not applied these efforts to the special risks for pregnancy among women with diabetes.

This approach involves reviewing the existing literature relevant to the topic and identifying key concepts, followed by formal narrative analyses from a panel of experts to elicit further insights beyond those already found in the literature. These narrative analyses identify factors that influence the associated risk, as well as qualitative relationships between the factors. The expert panel input is collected by moderating a discussion among experts and prompting them to consider what concepts are new and not well represented in the literature, as well as how those concepts relate to the literature and to one another.

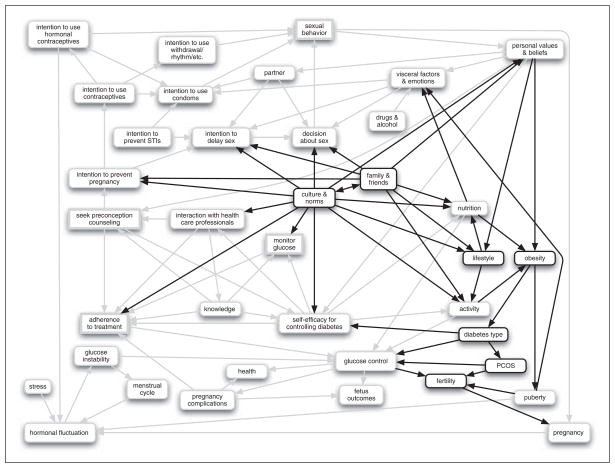

The scientific literature and narrative analyses are then organized into an influence diagram,30 which represents the key concepts that emerged as nodes, with causal and predictive links connecting them where appropriate, as determined by expert analysis of the relationships between concepts. Actions are shown in rectangular boxes, and variables that are affected by those actions are shown in rounded boxes.

A computationally tractable model29,31 provides a starting point for estimating the potential impacts of changing different actions (eg, delaying sexual activity, seeking preconception counseling). In situations like this one, where there are insufficient data to explicitly quantify the relationships between social variables, such computations are not actually performed. However, the model is intended as far as possible to be calculable to force its terms to be as explicit as possible to capture what is worth knowing, scientifically and practically. The resulting expert model is designed to identify intervention needs specific to the domain of interest, rather than general psychological processes. As a result, creating an expert model increases the opportunity for a subsequent intervention to correct misconceptions and dispel myths and to better guide the target audience to a complete understanding of the domain and to behavior that will lead to outcomes more in line with the goals and needs of individuals with T2D.

Literature Search

A literature review of scholarly articles published between January 1989 and January 2009 was performed using Ovid Medline and CINAHL. Search criteria included the key words adolescent, type 1 diabetes, type 2 diabetes, puberty, reproductive health, preconception care, preconception counseling, preconception planning, pregnancy, and congenital anomalies for articles published in English. Fifty-two articles were selected.

Participants

A panel of 9 experts, consisting of authors of this article, met in a panel discussion, with most attending in person and the rest by telephone conference call, in a single-session meeting. This group included experts in T1D and T2D, adolescence and diabetes, diabetes and sexual behavior, adolescent sexual decision making, gynecological implications of diabetes, minority health issues, and cultural diversity. The expert panel included African American and Caucasian participants.

Procedure

The primary author moderated the discussion, explaining the goal of the panel and beginning by offering a narrative of her basic understanding as a nonexpert in diabetes, which reflects the information from the literature shown by the light print in Figure 1. Experts were then each given an opportunity to provide their own narrative and were free to respond to one another’s claims. Expert input was based on clinical experience and familiarity with the scientific literature. At the close of the meeting, all experts indicated that they felt their expertise had been sufficiently summarized by the moderator and that their responses to others’ comments had been addressed and noted. Information was recorded by handwritten notes and a tape recorder. The lead author wrote a summary of the information shared during the panel and checked it against the audio recording for correctness and completeness. The summary was then sent to all members of the expert model for final validation.

Figure 1.

An integrated assessment of the key concepts described by the full expert model of preconception counseling and reproductive health for young women with diabetes, incorporating expert knowledge from the panel on the factors relevant to type 2 diabetes (bold color) with factors from the literature for women with type 1 diabetes (light color).

The resulting summary was then reviewed for unique concepts that added to the expert model of the literature on T1D and pregnancy risk. Concepts that were already represented in the larger literature on diabetes and reproductive health were confirmed against the preliminary expert model. New concepts (bold print) in Figure 1 were identified as potentially relevant to the model and were defined in terms described by the expert panel.

Results

Scientific Literature Model

Before conducting the expert panel discussion, an influence diagram was created representing the initial expert model reflecting the published literature. Figure 1 depicts the key variables and actions derived from the literature on preconception counseling and reproductive health for women with T1D (in light print) and expert knowledge from the panel on the factors relevant to T2D (in bold print). Such behaviors can be motivated by the constructs from the health belief model32 (included in personal values and beliefs). These key variables (barriers and benefits to seeking preconception counseling and intention to prevent an unplanned pregnancy, and susceptibility to the complications) are described only briefly here. The health belief model may focus attention on common elements to be addressed, such as barriers to implementing a behavior, with the mental models approach identifying the specific barriers relevant to the domain. The act of seeking preconception counseling (found in the middle of the left side of the model) is often prompted by interactions with health care professionals and existing knowledge and beliefs33; this act can go up in the model to affect the intention to prevent pregnancy, down to improve adherence to treatment, as well as into the center of the model to promote self-efficacy for controlling diabetes. Self-efficacy may also be a function of knowledge about diabetes management, interactions with health care professionals, and one’s personal values and beliefs, and it can affect behavior in terms of monitoring glucose and seeking adherence to treatment.33

The intention to prevent pregnancy eventually affects sexual behavior and pregnancy, via important constructs such as intentions to delay sex and use contraceptives,34 all of which may be affected by other influences such as intentions to prevent sexually transmitted infections (STIs),34 emotions, or the sexual partner.35 Once pregnant, poor glucose control can lead to problems with both the woman’s health and the fetus’ health as well as pregnancy complications that can adversely affect the fetus’ outcomes.4 It is important to note that glucose control, in addition to being affected by nutrition and activity, can be hampered by the glucose instability brought on, among other causes, by hormonal fluctuation, which may result from pregnancy, puberty, or use of hormonal contraceptives or which may vary with the menstrual cycle or increased stress. In turn, glucose instability can affect a woman’s menstrual cycle.3

This foundation was used as a starting point to gather new insights from the expert panel to expand the expert model to include relevant concepts that emerge with attention on adolescents with T2D (see Figure 1).

Expert Panel Model

There was broad agreement across all members of the expert panel, reflecting little contention around the issues that emerged. The experts’ narratives informed the development of the expert model and provided insights into particular aspects of T2D that are likely to become increasingly relevant as the population of adolescents with T2D grows. Below, paraphrases from the expert panel are presented; key elements from the panel’s insights have been italicized and were added in Figure 1 as darker bolded nodes. This new information will become critical points of preconception counseling specifically relevant for adolescents with T2D.

Behavioral implications of etiology and management of T2D versus T1D

Youth with T2D are usually diagnosed during adolescence and may have less experience managing their disease than those with T1D. Unlike T1D, which typically requires insulin for survival and to manage glucose control, adolescents with T2D are often treated with oral medication or through lifestyle intervention, including nutrition and activity changes.

With T2D, there is less risk of imminent, acute effects on health such as diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). However, failing to keep glucose control in check can lead to severe long-term effects on health, such as heart disease. Unlike adolescents with T1D, when those with T2D do not adhere to treatment (diet, exercise, medication, blood glucose monitoring) and miss doses of their medication, they usually do not suffer acute changes in their health. As a result, there is concern that adolescents with T2D may consider their disease to be less severe and therefore not have as much motivation or be as diligent about maintaining tight glucose control.

Culture and norms may further exacerbate this effect. People with T2D are disproportionately nonwhite. African Americans tend to be less trusting of health care professionals, which extends for some people to a reluctance to adhere to their treatment as prescribed. Furthermore, there may be a cultural tendency within these cultures to ascribe health conditions such as diabetes to “fate,” something that was caused by unknown forces over which they can take little control. As a result of these aspects of culture and norms, they may be less likely to change their lifestyle, including nutrition and activity, and they may have a diminished self-efficacy for controlling diabetes.

In addition, compared with Caucasian adolescents, African American adolescents are often expected to be less reliant on their families. T2D is frequently first diagnosed after puberty, leaving nonwhite adolescents with the expectation to take more responsibility for recommended changes to their lifestyle, including nutrition, activity, and adherence to treatment. Without strong support from their family, such major lifestyle changes are very difficult for an adolescent to initiate and maintain. An additional cultural factor among African Americans is the association of diabetes with obesity. Being overweight may be less negatively perceived within the African American community because larger body size is culturally associated with fertility, which is believed to be a sign of health. This perception makes it harder to promote losing weight as a strategy for maintaining glucose control.

Furthermore, recommended behavioral changes to combat diabetes sometimes conflict with the family routine or health history. It may be difficult for the overweight adolescents at risk for T2D to change their nutrition and activity as part of their lifestyle habits in the face of a family environment that reinforces both sedentary and dietary behaviors leading to obesity. Moreover, some family members may have diabetes themselves and may feel that it is “nothing to worry about”; as a result, their children may be less motivated to maintain good glucose control.

Implications for pregnancy

If a woman with diabetes gets pregnant when she is not in tight glucose control, she risks pregnancy complications, which may jeopardize the fetus’ outcome by leading to congenital malformation. Not getting glucose under control before and during the pregnancy may lead to negative consequences such as birth defects, preeclampsia, preterm delivery, neonatal intensive care admission, hyperbilirubinemia, respiratory distress, hypoglycemia, macrosomia, and electrolyte abnormalities. Birth defects can occur very early in the pregnancy, before the woman knows she is pregnant and seeks prenatal care. In addition, there may be long-term consequences for the children of women with diabetes during pregnancy, including childhood obesity and glucose intolerance. Awareness of genetic risks can help new parents to promote a healthy diet and active lifestyle to reduce their child’s risk of developing T2D and health consequences.

If a woman with T1D or T2D wants to avoid poor fetal outcomes and pregnancy complications, she must have tight glucose control before she conceives and must maintain tight control throughout the pregnancy. To achieve tight glucose control, all women with diabetes will need to rigorously monitor glucose levels and adjust their treatment accordingly. In preconception counseling, women with T2D are routinely transferred to insulin prior to a pregnancy, because as pregnancy progresses, glucose regulation requires more intensive management, which is best achieved with insulin. In addition, some oral medications for managing T2D can be teratogenic, and the safety of other oral agents (eg, metformin) during pregnancy are questionable; only limited data are available regarding pregnancy exposure.

Acute complications associated with T2D are often perceived as less severe than for T1D. Yet pregnancy-related complications are similar for both types of diabetes. Pregnant women with T2D, however, face different kinds of challenges compared with pregnant women with T1D. First, pregnant women with T2D who were managed on oral treatment or a careful diet and exercise regimen will need to change to insulin treatment to avoid pregnancy complications, along with dealing with unfamiliar, pregnancy-induced hormone fluctuations and related glucose instability. Second, severe acute health outcomes that are not typically associated with T2D, such as DKA, could occur during pregnancy. Because they have not faced these threats before, pregnant women with T2D may be less likely to recognize and treat them than pregnant women with T1D.

Implications for fertility and contraception

Young women with diabetes, however, could experience disruption in their menstrual cycle when they do not have good glucose control. Adolescents with T2D could likely be more fertile because obesity is related to earlier puberty. On the other hand, obese adolescents with T2D may have an increased risk for polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), a hormonal abnormality that is associated with infertility. This phenomenon has 2 important implications for young women who do not want to become pregnant. First, metformin, a common treatment of T2D and PCOS, helps to regulate their reproductive system, thus increasing their fertility. If they have come to believe that they may not be very fertile—perhaps because they have PCOS and diabetes, or because of irregular periods or previous unprotected sexual behavior has not led to pregnancy—they may not realize that their treatments are making it more likely that they will get pregnant if they have sex. Second, if they are not having periods regularly, they may not realize right away that they are pregnant, so that when they do find out, they have less time to achieve tight glucose control early in their pregnancy.

Ironically, because some young diabetic women know that they may have problems with pregnancy, they could wonder if they will ever be able to get pregnant. This question may lurk in the back of their minds or may even be contemplated often, and they may want to “find out now” by getting pregnant.

Birth control options for sexually active diabetic adolescents can be an issue. Some birth control methods may be easier but less effective than others (eg, withdrawal, rhythm). Other more effective methods, such as hormonal contraceptives, may cause changes in glucose control and may increase their risk of problems, including, for obese girls, further weight gain and hypertension. Furthermore, adolescents may not take the pill regularly or use condoms routinely. The health risks associated with hormonal contraceptives such as Depo-Provera shots or Ortho Evra patches that do not require daily action may be outweighed by the risks associated with an unplanned pregnancy.

Implications for sexual behavior

Obese and overweight girls, who are at higher risk for developing T2D, tend to go through puberty earlier. This may lead to sexual behavior at a younger age because of emerging sexual feelings coupled with a more mature physical appearance. These girls may receive more sexual overtures, possibly from older partners who affect sexual decisions. Many young women are already sexually active when they learn that they have diabetes and thus are already at risk for pregnancy and vulnerable to sexually transmitted infections and fungal vulvavaginitis. Furthermore, because T2D is associated with obesity, many of these young women may suffer from other psychosocial effects of being overweight, including low self-esteem, depression, disordered eating, and other problems that may lead them to act out in various ways. These outcomes may be even more typical of adolescents who neglect to prevent pregnancy when having sex, as a result of “taking life as it comes.” Thus, those who are least likely to act to avoid pregnancy may end up being the most vulnerable to the negative outcomes of a pregnancy.

T2D can also be associated with visceral factors and emotions that make adolescents feel less attractive, such as being obese, being hirsute, or having acne with PCOS. One way in which young women who are depressed or who have a poor self-image may try to find approval or comfort is by engaging in (often risky) sexual behavior to encourage a relationship. Such a relationship may satisfy these needs, and the idea of having a baby may appeal even more.

Discussion

T2D and its treatment can affect reproductive health. Raising awareness of these issues will be imperative to prevent problems. In preparation for developing a tailored preconception counseling program for adolescent girls with T2D, an expert panel was brought together for this formative stage of research. In starting to develop this expert model of T2D and reproductive health, several key issues emerged as critically important to this distinction. Five important insights emerged in considering how adolescents with T2D differ from those with T1D. First, T2D may be perceived as being a less severe disease because it can be treated with oral medication and lifestyle changes and because there are fewer severe acute complications.23 And since T2D is usually diagnosed during adolescence, newly diagnosed patients have much less experience managing their disease.23,36 This lack of experience contributes to their tendency not to react immediately to imbalances in blood glucose, leaving them less likely to maintain control over their blood glucose levels and at high risk for complications.37 This is especially true given that African American women tend to have higher initial A1C levels during diabetic pregnancies.38

Second, T2D is more prevalent among some minorities, such as the African American population, compared with T1D, which is found predominantly among Caucasians.23,39 African American children consume more dietary fat than Caucasian children, placing them at risk for obesity and insulin resistance, leading to T2D.39,40 Due to cultural factors, African American adolescents with T2D and their families may be less trusting of the medical establishment,41 and adolescents may be less likely to take control of their disease.18 Poor socioeconomic status can also perpetuate an unhealthy lifestyle, through lack of health insurance (especially to pay for diabetes management, including medication), lack of access to medical resources, lack of safe places to exercise where they live (especially for females), lack of healthy food in their neighborhood, and limited food choices.42 Adolescents from lower-income households tend to have more unhealthy behaviors.43 Thus, the etiology of T2D is complex and perhaps a combination of genetic, environmental, behavioral, and social factors.23

Third, the dramatic increase in the prevalence of T2D among youth has been associated with the rise in overweight and obesity.23,21,44 Furthermore, children of obese parents have a higher risk of becoming obese.45 Adolescents are influenced by their family’s lifestyle, which is often difficult for them to change. The family may model and promote sedentary behaviors and overnutrition, patterns that become established in the adolescent, resulting in psychological, physiological, and environmental patterns promoting obesity.45 These patterns include day-long access to calorie-dense, inexpensive foods, loss of structure to meals, and lack of regulated hunger-satiety feedback.45 In addition, family members with diabetes may provide models of adult relatives who do not take good care of their bodies and disease, reinforcing the attitude that good control does not matter. Alternatively, seeing diabetes as the cause of complications may lead some to recognize the need for better control, make them angry, or leave them in denial.

Fourth, adolescents with T2D could likely be more fertile, in part because they tend toward obesity, which is related to earlier puberty and menarche,46 which in turn is associated with earlier ovulatory frequency and thus early fertility.47 Also, T2D is more prominent among African Americans,23,36 who often experience earlier puberty,48,49 thus altering their self-image,50 which can lead to earlier sexual advances,46–52 and unintentional pregnancies.53 Fertility is also enhanced by medications such as metformin, used to treat T2D and PCOS, which is more common among adolescents with T2D.54 Other aspects of reproductive health could also be affected by diabetes.2,3 Young women with diabetes could experience disruption in their menstrual cycle when they do not have good glucose control.3 Such irregularities could make it difficult to plan or detect pregnancies.

Finally, because some oral agents for managing T2D can be teratogenic, women must transfer to insulin prior to a pregnancy.55 Because poorly controlled diabetes can also be teratogenic, insulin also makes it easier to fine-tune metabolic control.12,38

All of these factors could converge to affect reproductive health, such as puberty, menses, sexuality, perceived and actual fertility, and pregnancy. These factors could increase these adolescents’ risk of having an unplanned pregnancy and complications with their pregnancy. Taken together, these factors provide compelling reasons to create developmentally appropriate, culturally sensitive preconception counseling programs specifically tailored for teens with T2D. Preconception counseling is a cost-effective method that could decrease their risks of complications with reproductive health.4,5,56,57

The complexity of issues and their interrelatedness pose a challenge for future work on interventions to address pregnancy risks for adolescent girls with T2D. Receiving this advice well before a woman is considering a pregnancy can be very beneficial. Having such information together in a single, integrated description found in this article is intended to help future researchers to address the full domain of relevant issues in their work and to be confident that there are no major gaps in representing what is currently known by experts. The growing numbers of adolescents with T2D, as well as the cultural differences between this group and adolescents with T1D, will contribute to a public health crisis for these young women in the years to come if these risks are not addressed with effective prevention efforts. For such efforts to be effective, they must address the risks in ways that will work for this population. The results from this expert panel can inform research on this issue.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant R01 HD044097 (NIH/NICHD). The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Patricia Schmitt, Mandy Holbrook, and Charlotte Fitzgerald in helping to make possible the expert panel discussion and translation of those findings into this article.

Footnotes

For reprints and permission queries, please visit SAGE’s Web site at http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav.

References

- 1.Morgan MG, Fischhoff B, Bostrom A, Atman C. Risk Communication: The Mental Models Approach. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.LaMone P. Human sexuality in adults with IDDM. Image J Nurs Sch. 1993;25:101–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1993.tb00764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poirier L, Coburn K. Women & Diabetes: Life Planning for Health & Wellness. Alexandria, VA: American Diabetes Association; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kitzmiller JL, Buchanan TA, Kjos S, Combs CA, Ratner RE. Preconception care of diabetes, congenital malformations, and spontaneous abortions. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:514–541. doi: 10.2337/diacare.19.5.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kitzmiller JL, Gavin LA, Gin GD, Jovanovic-Peterson L, Main EK, Zigrang WD. Preconception care of diabetes: glycemic control prevents congenital anomalies. JAMA. 1991;256:731–736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elixhauser A, Weschler JM, Kitzmiller JL, et al. Cost-benefit analysis of preconception care of women with established diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1993;16:1146–1157. doi: 10.2337/diacare.16.8.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Combs C, Kitzmiller J. Spontaneous abortions and congenital malformations in diabetes. Baillières Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 1991;5:315–331. doi: 10.1016/s0950-3552(05)80100-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nankervis A, Werther GA, Court JM, editors. Sexual Function and Pregnancy, in Diabetes and the Adolescent. Melbourne, Australia: Miranova; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schroeder B, Hertweck S, Sanfilippo J, Foster MB. Correlation between glycemic control and menstruation in diabetic adolescents. J Reprod Med. 2000;45:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mills J, Baker L, Goldman A. Malformations in infants of diabetic mothers occur before the seventh gestational week. Diabetes. 1979;28:292–293. doi: 10.2337/diab.28.4.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller E, Hare JW, Cloherty JP, et al. Elevated maternal hemoglobin A1, in early pregnancy and major congenital anomalies in infants of diabetic mothers. N Engl J Med. 1981;304:1331–1334. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198105283042204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Diabetes Association. Preconception care of women with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:S76–S78. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2007.s76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cousins L. The California diabetes and pregnancy program: a statewide collaborative program for the preconception and prenatal women. Baillières Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 1991;5:443–460. doi: 10.1016/s0950-3552(05)80106-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Willhoite MB, Bennert HW, Palomaki GE, et al. The impact of preconception counseling on pregnancy outcomes: the experience of the Maine Diabetes in Pregnancy Program. Diabetes Care. 1993;16:450–455. doi: 10.2337/diacare.16.2.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Michel B, Charron-Prochownik D. Diabetes nurse educators and preconception counseling. Diabetes Educ. 2006;32:108–116. doi: 10.1177/0145721705284371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Charron-Prochownik D, Sereika SM, Wang SL, et al. Reproductive health and preconception counseling awareness in adolescents with diabetes: what they don’t know can hurt them. Diabetes Educ. 2006;32:235–242. doi: 10.1177/0145721706286895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Charron-Prochownik D, Hannan MF, Sereika SM, Becker D, Rodgers-Fischl A. How to develop CD-ROMs for diabetes education: exemplar “Reproductive-health Education and Awareness of Diabetes in Youth for Girls” (READY-Girls) Diabetes Spectrum. 2006;19:110–115. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Betchart-Roemer J. Type 2 Diabetes in Teens. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Court JM, Cameron FJ, Berg-Kelly K, Swift PGF. Diabetes in adolescence. Pediatr Diabetes. 2008;9:255–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2008.00409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pinhas-Hamiel O, Zeitler P. The global spread of type 2 diabetes mellitus in children and adolescents. J Pediatr. 2005;146:693–700. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosenbloom A, Joe JR, Young R, Winter W. Emerging epidemic of type 2 diabetes in youth. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:345–354. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.2.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Diabetes Association. Increasing incidence of type 2 diabetes in the third millennium: is abdominal fat the central issue? Diabetes Care. 2000;23:441–442. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.4.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Diabetes Association. Type 2 diabetes in children and adolescents. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:381–389. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.3.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beckles GLA, Thompson-Reid PE, editors. Diabetes and Women’s Health Across the Life Stages: A Public Health Perspective. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Division of Diabetes Translation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fischhoff B, Bruine de Bruin W, Güvenç Ü, Caruso D, Brilliant L. Analyzing disaster risks and plans: an avian flu example. J Risk Uncertain. 2006;33:131–149. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bruine de Bruin W, Downs JS, Fischhoff B. Adolescents’ thinking about the risks and benefits of sexual behavior. In: Lovett M, Shah P, editors. Thinking With Data. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Downs JS, Murray PJ, Bruine de Bruin W, Penrose J, Palmgren C, Fischhoff B. Interactive video behavioral intervention to reduce adolescent females’ STD risk: a randomized controlled trial. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59:1561–1572. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fischhoff B, Downs JS. Accentuate the relevant. Psychol Sci. 1997;8:154–158. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fischhoff B, Riley D, Kovacs DC, Small M. What information belongs in a warning? A mental models approach. Psychol Market. 1998;15:663–686. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clemens RT. Making Hard Decisions: Introduction to Decision Analysis. Belmont, CA: Duxbury; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Merz J, Fischhoff B, Mazur DJ, Fischbeck PS. Decision-analytic approach to developing standards of disclosure for medical informed consent. Journal of Toxics and Liability. 1993;15:191–215. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Becker MH, Rosenstock JM. Comparing social learning theory and the health belief model. In: Ward WB, editor. Advances in Health Education and Promotion. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press; 1987. pp. 45–249. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Janz NK, Herman WH, Becker M, et al. Diabetes and pregnancy: factors associated with seeking preconception care. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:157–165. doi: 10.2337/diacare.18.2.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kirby D. Effective approaches to reducing adolescent unprotected sex, pregnancy, and childbearing. J Sex Res. 2002;39:51–57. doi: 10.1080/00224490209552120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaestle CE, Morisky DE, Wiley DJ. Sexual intercourse and the age difference between adolescent girls and their romantic partners. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2002;34:304–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosenbloom AL, Silverstein JH. Type 2 Diabetes in Children & Adolescents. Alexandria, VA: American Diabetes Association; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hemachandra A, Ellis D, Lloyd CE, Orchard TJ. The influence of pregnancy on IDDM complications. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:950–955. doi: 10.2337/diacare.18.7.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Holcomb WL, Mostello DJ, Leguizamon G. African-American women have higher initial HbA1c levels in diabetic pregnancy. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:280–283. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.2.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arslanian S. Metabolic differences between Caucasian and African American children and the relationship to type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2002;15:509–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arslanian S, Saad R, Lewry V, et al. Hyperinsulinemia in African American children: decreased insulin clearance and increased insulin secretion and its relationship to insulin sensitivity. Diabetes. 2002;51:3014–3019. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.10.3014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reverby S. History of an apology: from Tuskegee to the White House. Research Practice. 2000;8:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taylor J, Franklin A. Psychosocial analysis of black teenage pregnancies: implications for public and cultural policies. Policy Stud Rev. 1994;13:157–164. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lowry R, Kann L, Collins JL, Kolbe L. The effects of socioeconomic status on chronic disease risk behaviors among US adolescents. JAMA. 1996;276:792–797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alberti G, Zimmet P, Shaw J, et al. Type 2 diabetes in the young: the evolving epidemic. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1798–1811. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.7.1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vivian E. Type 2 diabetes in children and adolescents—the next epidemic? Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22:297–306. doi: 10.1185/030079906X80495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Akers A, Lynch C, Gold M, et al. Exploring the relationship between obesity and sexual risk behaviors among female adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2008;42:45–46. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Apter D, Vihko R. Early menarche, a risk factor or breast cancer, indicates early onset of ovulatory cycles. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1983;57:82–86. doi: 10.1210/jcem-57-1-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Doswell W, Braxton B. Risk-taking behaviors in early adolescent minority women: implications for research and practice. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2002;4:31. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2002.tb00068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Doswell WM. The NIA group: building a sense of purpose in preadolescent African American girls. Nurs Leadersh Forum. 2004;8:95–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Doswell W, Millor G, Thompson H. Self-image and self-esteem in African-American preteen girls: implications for mental health. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 1998;19:71–94. doi: 10.1080/016128498249222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Doswell W, Kouyate M, Taylor J. Spirituality: a missing piece in preventive medicine: the health of African American adolescent girls and early sexual behavior. Am J Health Stud. 2003;18:195–202. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Doswell W, Kitutu J, McHenry B. The use of theoretical models to examine early sexual behavior in African American adolescent girls. Journal of Chi Eta Phi. 2004;50:15–20. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Finer LB, Henshaw SK. Disparities in rates of unintended pregnancy in the United States. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2006;38:90–96. doi: 10.1363/psrh.38.090.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zisser H. Polycystic ovary syndrome and pregnancy: is metformin the magic bullet? Diabetes Spectrum. 2007;20:85–89. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Langer O. Oral antidiabetic drugs in pregnancy: the other alternative. Diabetes Spectrum. 2007;20:101–105. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Herman WH, Janz NK, Becker MP, Charron-Prochownik D. Diabetes and pregnancy: preconception care, pregnancy outcomes, resource utilization and costs. J Reprod Med. 1999;44:33–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Herman W, Charron-Prochownik D. PC: an opportunity not to be missed. Clin Diabetes. 2000;18:122–123. [Google Scholar]