Abstract

Objective

To study whole-brain MR measures derived from diffusion tensor imaging and magnetization transfer imaging (MTI) for the in vivo assessment of cumulative neuropathologic changes in HIV and to evaluate the quantitative imaging strategies with respect to cognitive status measures including the severity of dementia and the degree of impairment in specific cognitive domains including attention, memory, constructional abilities, and motor speed.

Methods

Quantitative whole-brain measurements, including fractional anisotropy (FA), apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC), and magnetization transfer ratio (MTR), were derived from histograms and compared in HIV and control participants. Relationships between the MR and cognitive status measures were examined.

Results

Whole-brain FA and MTR were reduced in patients with HIV and correlated with dementia severity. Whole-brain MTR and ADC were correlated with psychomotor deficits. Evaluation of relationships between the studied MR measures indicated a correlation between ADC and MTR; FA was not correlated with either ADC or MTR.

Conclusions

Findings from this investigation support the use of quantitative whole-brain MR measures for evaluation of disease burden in HIV. Reductions in whole-brain fractional anisotropy and magnetization transfer ratio (MTR) distinguished HIV and control subjects, and these measures were associated with dementia severity. Relationships were identified between whole-brain MTR and apparent diffusion coefficient and psychomotor deficits. Combining these quantitative strategies in neuroimaging examinations may provide more comprehensive information concerning ongoing changes in the brains of HIV patients.

Various lines of evidence indicate that HIV enters the brain early in the course of infection.1 Early phases of brain involvement may be asymptomatic for indefinitely prolonged periods, with eventual cognitive deterioration involving loss of psychomotor speed, memory, motor skills, and learning capacity, with relative sparing of language, judgment, perceptual processes, and abstraction.2 Factors underlying the onset of cognitive decline, the time course of progression, and the selective loss of function have not yet been determined.

Injury to the brain in HIV involves aggregate effects of neurotoxic viral proteins (e.g., gp120 and Tat) and the consequences of immune activation.3 Conventional T1-weighted and T2-weighted MR images reveal white matter hyperintensities and atrophic brain changes in some patients with HIV dementia. Conventional MR images, however, may not adequately represent early sublethal tissue alterations or cumulative extent of injury. Studies correlating MR findings with neuropathology have found that conventional imaging is insensitive to microscopic injury in HIV patients.4

Quantitative imaging strategies such as diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) and magnetization transfer imaging (MTI) have been used to measure otherwise unobservable changes (e.g., in membranes)5 and to quantify tissue change on a microstructural scale that better approximates cellular dimensions.6 These noninvasive strategies have been exploited to quantify change from both sublethal and more destructive injury and have been used in some investigations to determine putative measures of whole-brain disease burden.7,8

This investigation evaluated quantitative indexes, including fractional anisotropy (FA), apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC), and magnetization transfer ratio (MTR), for measurement of whole-brain disease burden in HIV patients. The derived whole-brain MR measures were evaluated with respect to the severity of dementia and degree of impairment in specific cognitive domains involving attention, memory, constructional, motor, and executive functions.

Methods

Participants

Seropositive subjects (mean age 46 ± 6.7 years; seven men and two women) included nine well-characterized, medically stable patients participating in a longitudinal investigation of the natural history of neurologic impairment in advanced HIV infection. Control subjects included nine healthy volunteers, without history of neurologic illness (mean age 39 ± 9 years; seven men and two women). There were no significant differences between the groups in age or years of education. Self-reported seropositivity was confirmed by ELISA and western blot. All control subjects reported HIV seronegativity. Chronic neurologic disorders, current or past opportunistic CNS infection, and psychosis at study entry were among study exclusion criteria. All HIV subjects were on antiretroviral regimens; however, one patient’s therapy was temporarily suspended at the time of the scan.

Clinical assessments of the HIV subjects included the Macro-Neurologic Examination created by the AIDS Clinical Trials Group and the motor portion of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale, used to assess extrapyramidal signs. The neuropsychological examination evaluated working memory, verbal memory, visual memory, constructional ability, psychomotor, motor speed, and frontal/executive systems based on composites of individual subtests included in the battery. Dementia severity was determined on the basis of criteria defined by the American Academy of Neurology (AAN)9 and the Memorial Sloan–Kettering Rating Scale (MSK).10 The Karnofsky Performance Scale was also used to assess functional status.11 Both AAN and MSK criteria have been operationalized for uniform staging across multiple research sites.12,13 The operationalized MSK scoring takes into account the presence of CNS abnormalities on examination, the results of the neuropsychological testing, and the degree of impairment in work, self-care, and mobility status reported by the patient. A reported deficit in at least one of the eight instrumental activities of daily living is required to meet the minimal functional criterion for MSK staging. The AAN ratings were determined based on the degree of impairment on the neuropsychological tests using an extensively validated computer algorithm that has been used in many prior studies of HIV dementia.12 The derivation of the cognitive domain measures and the operational definitions of the dementia severity ratings have been described in more extensive detail previously.12,13 MSK, AAN, and Karnofsky scores for each subject are presented in table 1. CD4 counts for the HIV subjects ranged from 24 to 427; plasma viral load ranged from undetectable to 154,938 copies/mL.

Table 1.

Dementia severity measures for HIV and control subjects

| Controls | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV | |||||||

| Subject no. |

MSK | AAN | Karnofsky | Subject no. |

MSK | AAN | Karnofsky |

| 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 100 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| 2 | 0.5 | 0 | 90 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| 3 | 0.5 | 1 | 100 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| 4 | 0.5 | 1 | 80 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| 5 | 0.5 | 2 | 80 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| 6 | 1 | 2 | 75 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| 7 | 1 | 2 | 65 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| 8 | 1 | 2 | 60 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| 9 | 2 | 2 | 80 | 9 | 0.5 | 0 | 100 |

MSK = Memorial Sloan–Kettering; AAN = American Academy of Neurology.

MRI and image processing

Studies were performed on a 1.5 T twin-speed MR unit using the zoom gradient. A quadrature birdcage head coil was used for radiofrequency transmission and signal reception. Subjects were scanned using a comprehensive MRI protocol, including DTI, MTI, and T2-weighted and proton density–weighted imaging. An identical set of contiguous 7-mm axial slices covering the whole brain was used for the DTI and MTI sequences. This allowed coregistration among studies.

DTI was performed with an echo planar sequence and a bandwidth of ±125 kHz using the dual spin echo option to minimize distortion. Six diffusion-weighted images were acquired of each slice, with a b value of 1,000 s/mm2. A b = 0 reference image was also acquired. Diffusion gradients were applied along six directions: . The entire brain was imaged, from the base of the cerebellum to the top of the skull, using 22 contiguous 7-mm axial slices with field of view = 24 cm, matrix size = 128 × 128, repetition time (TR) = 7,000 milliseconds, and number of excitations = 4. The sequence used for MTI was a fast gradient echo with a low flip angle (20°) and long TR (TR = 1,000 milliseconds) to achieve minimal T1 weighting. The sequence was run twice, once preceded by an off-resonant saturation pulse (MT pulse) and once without the saturation pulse. The frequency offset of the saturation pulse was 1,200 Hz with duration of 16 milliseconds. The same shim parameters and receiver gain were maintained between the two acquisitions. The MT was determined based on the normalized intensity difference between the resulting images. The proton density– and T2-weighted images were acquired using a dual echo sequence with TR =3,300 milliseconds and echo time = 25 and 85 milliseconds.

Quantitative image analysis was performed off-line on a Linux workstation using customized image-processing routines written in MatLab (Mathworks, Natick, MA). The eigenvectors and eigenvalues of the DT were calculated for each voxel and used to produce maps of ADC and FA14:

where

where D1, D2, and D3 are the eigenvalues of the DT.

To obtain whole-brain statistics for FA and ADC, the background noise was first segmented out from tissue by applying an automated thresholding technique to the diffusion-weighted images. This also removed voxels containing predominantly CSF, as these have low intensity on diffusion-weighted images. Extracranial structures were excluded from the remaining mask by manual segmentation. FA measures (dimensionless) were expressed as root mean squares; whole-brain peak ADCs were in units of 10−3 mm2/s, hereafter referred to as whole-brain FA and whole-brain ADC.

Maps of the MTR were obtained using the relation

where Ms and M0 are the signal intensities in a given voxel obtained with and without the MT saturation pulse. CSF was segmented from brain parenchyma using the MT image, and a histogram of the MTR over the whole brain was produced, from which estimates were obtained of the peak MTR.

Statistical analyses

Primary dependent measures included the whole-brain MR measures compared in HIV and control subjects. Dementia severity (AAN, MSK, and Karnofsky) and neuropsychological measures of specific cognitive functions were also examined. Analyses were executed with SPSS (release 10.0; Chicago, IL). All statistical tests were two tailed with the exception of the between-group comparison for MTR. Because injury is strictly associated with reduction in this measure, a directional hypothesis was tested.

Results

Whole-brain FA measures were reduced in the HIV subjects (p = 0.05). The whole-brain MTR measures also differed between HIV and control subjects (p = 0.02). There were no significant between-group differences for whole-brain ADC. Means (SD) for the whole-brain MR indexes are presented in table 2.

Table 2.

Means (SD) for whole-brain MR measures

| Measure | HIV | Controls |

|---|---|---|

| FA | 0.30 (0.01) | 0.32 (0.02) |

| ADC | 0.79 (0.02) | 0.78 (0.02) |

| MTR, % | 46.5 (0.90) | 47.2 (0.50) |

FA = fractional anisotropy; ADC = apparent diffusion coefficient; MTR = magnetization transfer ratio.

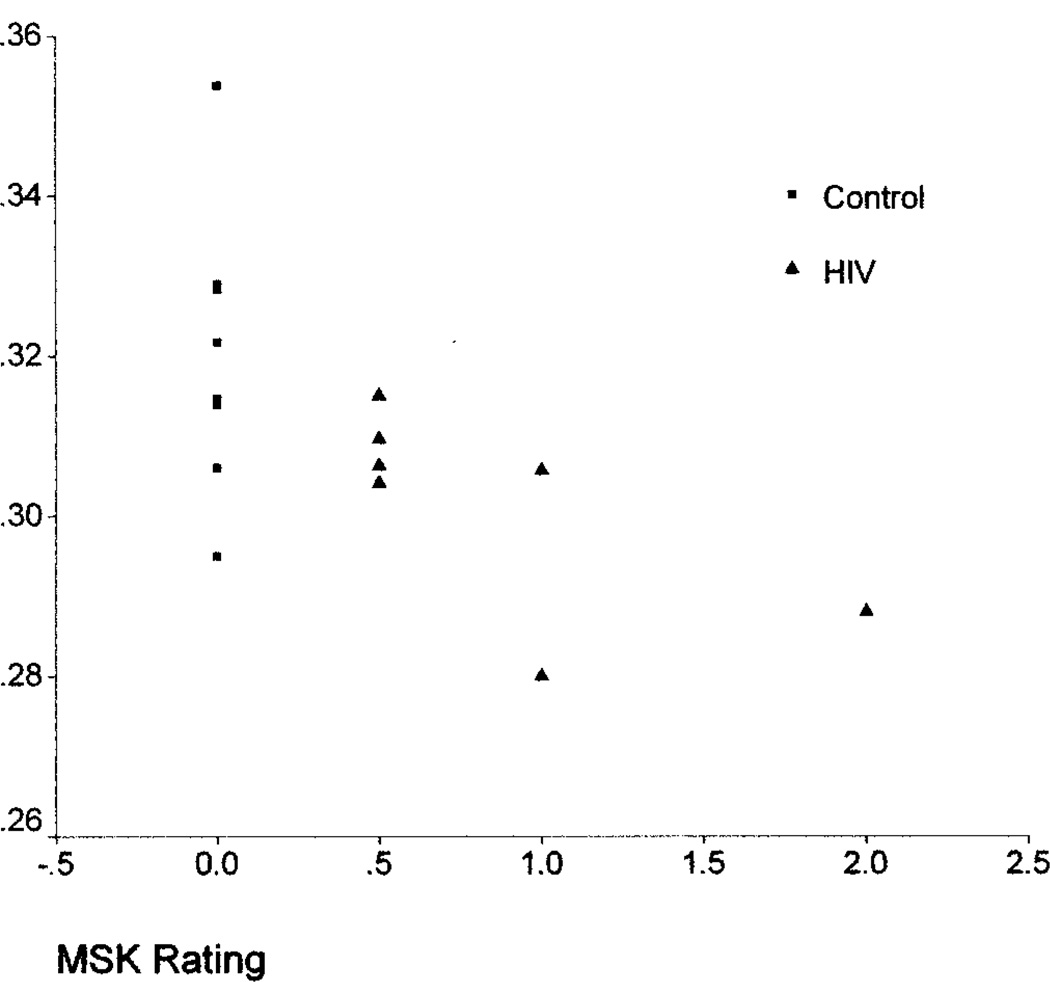

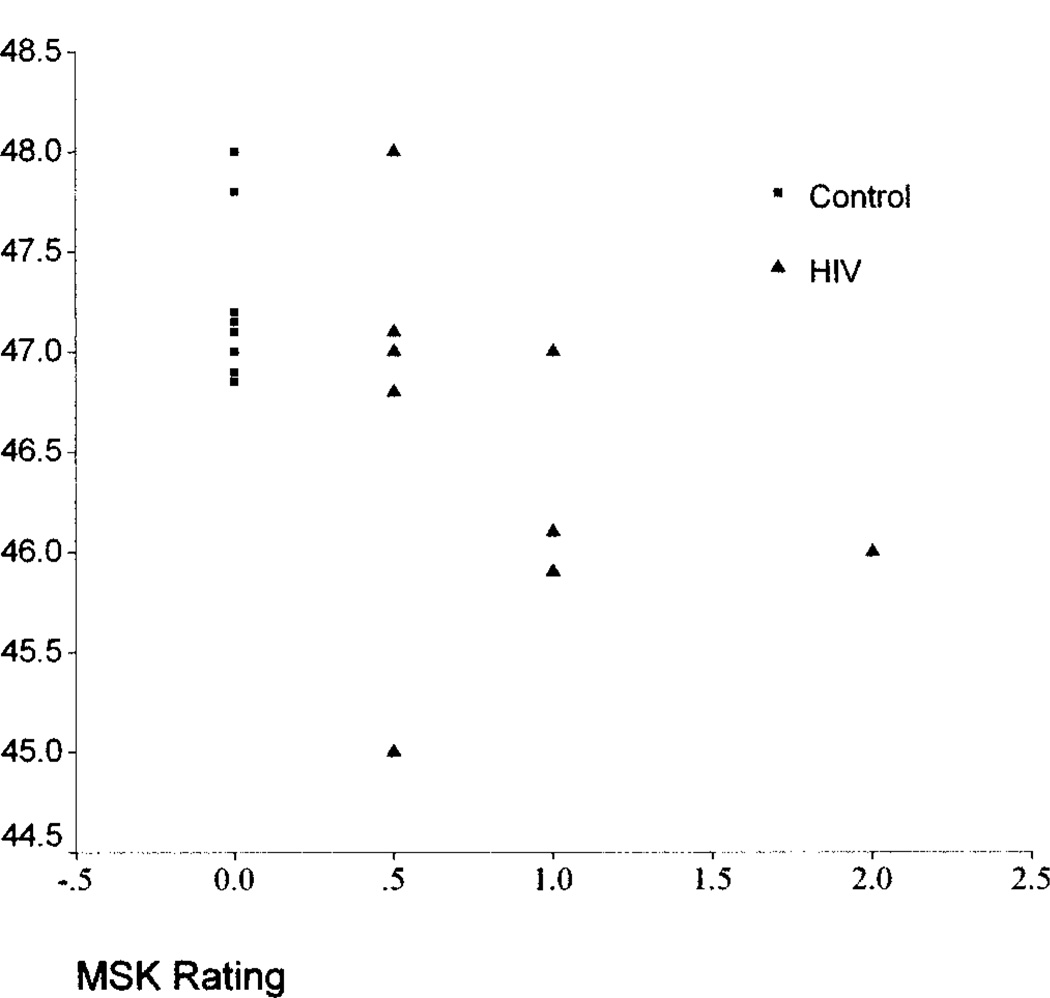

Further analyses examined relationships between the whole-brain measures and dementia severity ratings. Whole-brain FA was associated with MSK (ρ = −0.56, p = 0.04) and Karnofsky (ρ = 0.63, p = 0.015) scores; the relationship with AAN was nearly significant (ρ = −0.53, p = 0.06). Whole-brain MTR measures were also associated with MSK (ρ = −0.60, p = 0.01) and AAN (ρ = −0.65, p = 0.007) and nearly associated with the Karnofsky (ρ = 0.47, p = 0.06) ratings. Whole-brain ADC was not associated with the dementia severity ratings. The associations between the MSK ratings and the FA and MTR measures are shown in figures 1 and 2. Examination of the degree of relationship between whole-brain MR quantities indicated a correlation between ADC and MTR (r = −0.79, p = 0.001). FA was not correlated with either ADC or MTR. Clinical status measures, including CD4 counts, plasma viral load, and body mass index, were not associated with the whole-brain MR indexes in the HIV subjects.

Figure 1.

Relationship between whole-brain fractional anisotropy and Memorial Sloan–Kettering (MSK) ratings.

Figure 2.

Relationship between whole-brain magnetization transfer ratio and Memorial Sloan–Kettering (MSK) ratings.

Table 3 presents correlations between the whole-brain MR quantities and the degree of impairment in specific cognitive domains. Relationships were identified between whole-brain ADC (r = −0.53, p = 0.05) and MTR (r = 0.51, p = 0.04) and the psychomotor cognitive domain (digit symbol test). These findings motivated further examination of relationships between the whole-brain MR quantities and individual motor function tests in the neuropsychological battery. Specifically, subtests comprising the psychomotor and motor speed cognitive domain (grooved pegboard and timed gait) were examined individually. In addition to the relationship with the digit symbol test, MTR was associated with loss of fine motor control in the dominant hand (grooved pegboard; r = 0.52, p = 0.03); no relationships were found for other motor subtests including the timed gait measure of gross motor speed (table 4).

Table 3.

Whole-brain MR and cognitive domain relationships

| Cognitive domain | FA | ADC | MTR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Working memory | 0.19 | 0.08 | −0.11 |

| Verbal memory | −0.23 | −0.02 | 0.27 |

| Visual memory | 0.39 | −0.31 | 0.35 |

| Constructional | 0.27 | −0.37 | 0.27 |

| Psychomotor | 0.36 | −0.53* | 0.51* |

| Motor speed | 0.30 | −0.03 | 0.32 |

| Frontal executive | −0.49 | −0.02 | −0.03 |

p ≤ 0.05.

FA = fractional anisotropy; ADC = apparent diffusion coefficient; MTR = magnetization transfer ratio.

Table 4.

Whole-brain MR and motor subtest relationships

| Cognitive domain | Subtest | FA | ADC | MTR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychomotor | Digit symbol | 0.36 | −0.53* | 0.51* |

| Motor speed | GP dominant hand | 0.39 | −0.40 | 0.52* |

| GP nondominant | −0.23 | −0.15 | 0.32 | |

| Timed gait | 0.33 | 0.20 | −0.06 |

p ≤ 0.05.

FA = fractional anisotropy; ADC = apparent diffusion coefficient; MTR = magnetization transfer ratio; GP = grooved pegboard.

Discussion

In this investigation, whole-brain FA and MTR measures were reduced in HIV patients and associated with the overall severity of dementia. The findings are consistent with prior DTI studies indicating localized anisotropy abnormalities in HIV patients.15,16 Relationships between diffusion measures and functional status have been identified in other CNS disorders17,18 and in studies of normal cognition.19 Similarly, MTR has been found to be sensitive to HIV neuropathology,20,21 and reductions in whole-brain MTR measures correspond to the cognitive status of HIV patients.7

Examination of patterns of relationship with specific functional losses indicates associations between whole-brain ADC and MTR measures and psychomotor impairment (digit symbol test). MTR was also associated with loss of fine motor control (for the dominant hand). These results are consistent with findings in other CNS disorders indicating associations between psychomotor impairment and aggregate MTR22 and DTI18 measures. In HIV patients, motor losses are considered among the most sensitive indicators of early cognitive decline23 and have been used to monitor response to treatment.24 Psychomotor slowing is associated with dementia progression25–27 and HIV encephalitis at autopsy.27

Whole-brain FA was not correlated with the other MR measures examined in this investigation; a relationship was identified between MTR and ADC. Previous studies have also found lack of relationship between FA and MTR28,29 and correlations between reduced MTR and increased diffusivity (ADC) in injured brain tissue.30,31 Taken together, the findings suggest that the whole-brain measures do not confer redundant information concerning neuropathologic changes in HIV. Autopsy findings in HIV dementia patients indicate pronounced tissue alterations in both white matter and subcortical gray matter structures in HIV dementia.32 Of the examined MR quantities, FA may be the most specific to loss of white matter integrity. Whereas FA is a measure of intrinsic changes in directionally ordered tissue (e.g., white matter fiber tracts), diffusion in gray matter is generally isotropic.6 Whole-brain MTR and ADC may reflect both white and gray matter injury.

Although the pathologic significance of the studied MR measures is not yet fully understood, some cautious inferences can be put forth based on the obtained results. In this study, both whole-brain FA and MTR were predictive of the severity of dementia. Axonal injury has been associated with neurologic outcome in both white matter diseases and CNS infections33 and may play an important role in cognitive decline in HIV patients.34 Autopsy examinations using sensitive quantitative markers for detecting early injury (β-amyloid precursor protein immunoreactivity) indicate widespread axonal damage with approximate perivascular distribution in subcortical white matter, basal ganglia, and brainstem in tissue samples from HIV encephalitis patients.35 Histopathologic studies of multiple sclerosis tissue samples indicate that both MTR36,37 and anisotropy (FA) measures are highly associated with axonal damage; the degree of association with ADC measures was less pronounced.37

This investigation found a relationship between whole-brain MTR and ADC, and both measures were associated with psychomotor impairment. Factors such as membrane permeability and the relative volume and morphology of the extracellular space are determinants in both the measured ADC and the MTR.5,38 Available evidence suggests that these MR measurements may correspond to heterogeneous underlying mechanisms, including blood–brain barrier impairment, inflammation (e.g., macrophage and microglial activation), and factors associated with expansion of the extracellular space, including irreversible tissue change.5 Injury in frontal–subcortical regions is a plausible basis for psychomotor impairment and consistent with MR spectroscopy findings in HIV patients.39 MR spectroscopy studies have found elevations in a marker of membrane damage (choline) in asymptomatic HIV patients.40,41 Elevations in a marker of glial activation and astrogliosis (myo-inositol/creatine) have been found in the basal ganglia among HIV patients with prominent psychomotor slowing.42,43 Subcortical levels of N-acetylaspartate, a neuronal injury marker, have been associated with motor impairment (grooved pegboard test),40 and whole-brain measures (NAA concentration) have been found to be predictive of impaired performance on a composite of psychomotor and reaction time tests.44

It is likely that various pathologic processes acting in concert are required to account for cumulative brain injury in HIV patients. The principal advantage of whole-brain imaging strategies is to provide a means of objectively quantifying aggregate disease burden in vivo. These strategies may be useful, for example, for monitoring clinical course and response to therapy. Some functional losses in HIV patients, however, may be better predicted by localized tissue status measurements. Further studies are needed to delineate mechanisms of injury corresponding to tissue status measurements in specific brain regions.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Linda Pierchala, Linda Reisberg, Pottumarthi Prasad, and Qun Chen for their assistance.

Supported by K23 MH66705 (A.B.R.) and NIH/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke NS36519 (L.G.E.).

References

- 1.An SF, Giometto M, Miller RF, et al. Axonal damage revealed by accumulation of beta-APP in HIV-positive individuals without AIDS. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1997;56:1262–1268. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199711000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lipton SA, Gendelman HE. Seminars in medicine of the Beth Israel Hospital, Boston. Dementia associated with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:934–940. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199504063321407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaul M, Garden GA, Lipton SA. Pathways to neuronal injury and apoptosis in HIV-associated dementia. Nature. 2001;410:988–994. doi: 10.1038/35073667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Everall IP, Chong WK, Wilkinson ID, et al. Correlation of MRI and neuropathology in AIDS. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1997;62:92–95. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.62.1.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Buchem MA, McGowan JC, Grossman RI. Magnetization transfer histogram methodology: its clinical and neuropsychological correlates. Neurology. 1999;53:S23–S28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Basser PJ, Pierpaoli C. Microstructural and physiological features of tissues elucidated by quantitative-diffusion-tensor MRI. J Magn Res [B] 1996;111:209–219. doi: 10.1006/jmrb.1996.0086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ge Y, Kolson DL, Babb JS, Mannon LJ, Grossman RI. Whole brain imaging of HIV-infected patients: quantitative analysis of magnetization transfer ratio histogram and fractional brain volume. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24:82–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ragin AB, Storey P, Cohen BA, Epstein LG, Edelman RR. Whole brain diffusion tensor imaging in HIV-associated cognitive impairment. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2004;25:195–200. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Janssen RS, Cornblath DR, Epstein LG, et al. Nomenclature and research case definitions for neurological manifestations of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 (HIV-1) infection. Report of a Working Group of the American Academy of Neurology AIDS Task Force. Neurology. 1991;41:778–785. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.6.778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Price RW, Brew BJ. The AIDS dementia complex. J Infect Dis. 1988;158:1079–1083. doi: 10.1093/infdis/158.5.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karnofsky DA, Abelman WH, Craver LF, et al. The use of nitrogen mustards in the palliative treatment of carcinoma. Cancer. 1948;1:634–656. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marder K. The Dana Consortium on Therapy for HIV Dementia and Related Cognitive Disorders. Clinical confirmation of the American Academy of Neurology algorithm for HIV-1-associated cognitive/motor disorder. Neurology. 1996;47:1247–1253. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.5.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marder K, Albert SM, McDermott MP, et al. Inter-rater reliability of a clinical staging of HIV-associated cognitive impairment. Neurology. 2003;60:1467–1473. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000064172.46685.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ulug AM, van Zijl PC. Orientation-independent diffusion imaging without tensor diagonalization: anisotropy definitions based on physical attributes of the diffusion ellipsoid. J Magn Res Imag. 1999;9:804–813. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2586(199906)9:6<804::aid-jmri7>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Filippi CG, Uluğ AM, Ryan E, Ferrando SJ, van Gorp W. Diffusion tensor imaging of patients with HIV and normal-appearing white matter on MR images of the brain. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22:277–283. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pomara N, Crandall DT, Choi SJ, Johnson G, Lim KO. White matter abnormalities in HIV-1 infection: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Psychiatry Res. 2001;106:15–24. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4927(00)00082-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bozzali M, Falini A, Franceschi M, et al. White matter damage in Alzheimer’s disease assessed in vivo using diffusion tensor magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;72:742–746. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.72.6.742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rovaris M, Iannucci G, Falautano M, et al. Cognitive dysfunction in patients with mildly disabling relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis: an exploratory study with diffusion tensor MR imaging. J Neurol Sci. 2002;195:103–109. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(01)00690-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moseley M, Bammer R, Illes J. Diffusion-tensor imaging of cognitive performance. Brain Cogn. 2002;50:396–413. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2626(02)00524-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dousset V, Armand J, Huot P, Viaud B, Caille J. Magnetization transfer imaging in AIDS-related diseases. Neuroimag Clin North Am. 1997;7:447–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ernst T, Chang L, Witt M, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy and human immunodeficiency virus–associated white matter lesions in AIDS: magnetization transfer MR imaging. Radiology. 1999;210:539–543. doi: 10.1148/radiology.210.2.r99fe19539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van der Flier WM, van den Heuvel DMJ, Weverling-Rijnsburger AWE, et al. Cognitive decline in AD and mild cognitive impairment is associated with global brain damage. Neurology. 2002;59:874–879. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.6.874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Selnes OA, Galai N, Bacellar H, et al. Cognitive performance after progression to AIDS: a longitudinal study from the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. Neurology. 1995;45:267–275. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sacktor NC, Lyles RH, Skolasky RL, et al. Combination antiretroviral therapy improves psychomotor speed performance in HIV-seropositive homosexual men. Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS) Neurology. 1999;52:1640–1647. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.8.1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sacktor NC, Bacellar H, Hoover DR, et al. Psychomotor slowing in HIV infection: a predictor of dementia, AIDS and death. J Neurovirol. 1996;2:404–410. doi: 10.3109/13550289609146906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bouwman FH, Skolasky RL, Hes D, et al. Variable progression of HIV-associated dementia. Neurology. 1998;50:1814–1820. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.6.1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dunlop O, Bjørklund R, Bruun JN, et al. Early psychomotor slowing predicts the development of HIV dementia and autopsy-verified HIV encephalitis. Acta Neurol Scand. 2002;105:270–275. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2002.9o188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iannucci G, Rovaris M, Giacomotti L, Comi G, Filippi M. Correlation of multiple sclerosis measures derived from T2 weighted, T1 weighted, magnetization transfer and diffusion tensor MR imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22:1462–1467. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo AC, Jewells VL, Provenzale JM. Analysis of normal-appearing white matter in multiple sclerosis: comparison of diffusion tensor MR imaging and magnetization transfer imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22:1893–1900. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Inglese M, Salvi F, Iannucci G, Mancardi GL, Mascalchi M, Filippi M. Magnetization transfer and diffusion tensor MR imaging of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2002;23:267–272. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cercignani M, Iannucci G, Rocca MA, Comi G, Horsfield MA, Filippi M. Pathologic damage in MS assessed by diffusion-weighted and magnetization transfer MRI. Neurology. 2000;54:1139–1144. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.5.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bell JE. The neuropathology of adult HIV infection. Rev Neurol. 1998;154:816–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Medana IM, Esiri MM. Axonal damage: a key predictor of outcome in human CNS diseases. Brain. 2003;126:515–530. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giometto B, An SF, Groves M, et al. Accumulation of [beta]-amyloid precursor protein in HIV encephalitis: relationship with neuropsychological abnormalities. Ann Neurol. 1997;42:34–40. doi: 10.1002/ana.410420108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raja F, Sherriff FE, Morris CS, Bridges LR, Esiri MM. Cerebral white matter damage in HIV infection demonstrated using β-amyloid precursor protein immunoreactivity. Acta Neuropathol. 1997;93:184–189. doi: 10.1007/s004010050601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Waesberghe JHTM, Kamphorst W, de Groot CJA, et al. Axonal loss in multiple sclerosis lesions: magnetic resonance imaging insights into substrates of disability. Ann Neurol. 1999;46:747–754. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199911)46:5<747::aid-ana10>3.3.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mottershead JP, Schmierer K, Clemence M, et al. High field MRI correlates of myelin content and axonal density in multiple sclerosis. A post-mortem study of the spinal cord. J Neurol. 2003;250:1293–1301. doi: 10.1007/s00415-003-0192-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beaulieu C. The basis of anisotropic water diffusion in the nervous system—a technical review. NMR Biomed. 2002;15:435–455. doi: 10.1002/nbm.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chang L, Ernst T, Witt MD, Ames N, Gaiefsky M, Miller E. Relationships among brain metabolites, cognitive function, and viral loads in antiretroviral-naive HIV patients. Neuroimage. 2002;17:1638–1648. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meyerhoff D, Bloomer C, Cardenas W, Norman D, Weiner MW, Fein G. Elevated subcortical choline metabolites in cognitively and clinically asymptomatic HIV+ patients. Neurology. 1999;52:995–1003. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.5.995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tracey I, Carr CA, Guimaraes AR, Worth JL, Navia BA, Gonzalez RG. Brain choline-containing compounds are elevated in HIV-positive patients before the onset of AIDS dementia complex: a proton magnetic resonance spectroscopic study. Neurology. 1996;46:783–788. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.3.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.von Giesen HJ, Wittsack HJ, Wenserski F, Koller H, Hefter H, Arendt G. Basal ganglia metabolite abnormalities in minor motor disorders associated with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:1281–1286. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.8.1281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wenserski F, von Giesen HJ, Wittsack HJ, Aulich A, Arendt G. Human immmunodeficiency virus 1–associated minor motor disorders: perfusion-weighted MR Imaging and H MR spectroscopy. Radiology. 2003;228:185–192. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2281010683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Patel SH, Inglese M, Glosser G, Kolson DL, Grossman RI, Gonen O. Whole-brain N-acetylaspartate level and cognitive performance in HIV infection. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24:1587–1591. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]