Abstract

Three-dimensional (3D) TiO2 hierarchical structures with various microstructures have been successfully synthesized via a surfactant-free and single-step solvothermal route, in which hydrochloric acid (HCl), nitric acid (HNO3), and acetic acid (HAc) are employed as the acid medium, respectively. The effects of acid medium on the microstructures and properties of 3D TiO2 hierarchical structure have been studied. The results indicate that 3D dandelion-like microspheres assembled of radial rutile nanorods are obtained in the sample prepared with HCl. Both the fraction of rutile and the diameter of nanorod enhance with the increasing HCl concentration. For the products derived from either HNO3 or HAc, 3D spheres composed of anatase nanoparticles are present. The 3D dandelion-like TiO2 hierarchical structures show low reflectance and efficient light harvesting since this ordered rod geometry offers a light-transfer path for incident light as well as multiple reflective and scattering effects. Moreover, 3D TiO2 with this unique topology shows superior photocatalytic activity despite low surface area, which can be ascribed to the enhanced light harvesting, fast electron transport, and low electron/hole recombination loss.

Keywords: Three-dimensional, TiO2, Acid, Solvothermal, Optical properties, Photocatalytic activity, 60, 61.46.Km, 62.23.St

Background

Titania (TiO2) is widely used in various applications such as photocatalysis of pollutants, catalyst for selective catalytic reduction, photosplitting of water, transparent conducting electrode for dye-sensitized solar cells, electrolyte for proton exchange membrane fuel cells, etc. because of its nontoxicity, low-cost, and chemical stability [1-9]. In the past decades, many efforts have been exerted to the research of nanostructured TiO2[10-12]. Numerous studies have revealed that the properties and performance definitely depend on the crystal structures, grain sizes, and morphologies of the TiO2 nanostructures [13-15]. Therefore, controlled preparation of TiO2 nanostructures is of great scientific and industrial importance. Solvothermal synthesis provides an easy route to prepare a controllable oxide in one step in a tightly closed vessel [16]. TiO2 with different structural forms and morphologies has been yielded under diverse solvothermal conditions [17]. Among the various parameters, acid medium and its amount in a solvothermal reaction have been proved to play a substantial role in the control of the morphology and crystal structure of TiO2[16,18,19].

On the other hand, it becomes more and more evident that three-dimensional (3D) TiO2 assembled with ordered nanostructures under well control may bring some novel and unexpected properties because of its dimension and unique topology [20,21]. For instance, when used as a photocatalyst, 3D microscale TiO2 powder is less likely to aggregate and easy to be separated from the solution as compared to nanometer-scale powders [22]. Moreover, the optical properties and photocatalytic activity have been proven to be significantly dependent on the microstructure of 3D TiO2. Recently, synthesis of 3D ordered TiO2 assemblies of nanoparticles, nanorods, nanowires, and nanotubes have been reported [23-26], for instance, interesting dandelion-like structures [23,26], but the performance and properties are rarely investigated. In our previous work, 3D dandelion-like TiO2 structures self-assembled of nanorods have been synthesized in nonpolar solvent based on the water-nonpolar solvent interface via a surfactant-free and single-step solvothermal route [27]. Lately, our subsequent study revealed that the acid medium is essential to the microstructures, optical absorption, diffuse reflectance properties and, consequently, photocatalytic activities of the synthesized 3D TiO2 structures. However, the effects of acid medium on the microstructures and properties of 3D TiO2 hierarchical structures have not been reported.

Herein, 3D TiO2 hierarchical structures with distinct microstructures have been synthesized in various acid media via a surfactant-free and single-step solvothermal route. Hydrochloric acid, nitric acid, and acetic acid were employed in the present systems as the acid medium, respectively. The effects of acid media, including the type and concentration, on the microstructures of TiO2 products were studied. The optical absorption and diffuse reflectance as well as photocatalytic performance of 3D TiO2 hierarchical structures were investigated.

Methods

Synthesis

The synthesis of TiO2 samples was based on our previous report with some modifications [27]. All the chemicals were of analytic grade and used without further purification. Titanium n-butoxide (TNB) (Ti(OC4H9)4) and n-hexane (CH3(CH2)4CH3) were used as the titanium precursor and the solvent, respectively. The acid medium introduced in this study includes hydrochloric acid (HCl) (36.5 to 38 wt.%), nitric acid (HNO3) (65 to 68 wt.%), and acetic acid (HAc) (CH3COOH). In a typical synthesis, 0.45 M TNB and 0.90 M solution of acid were added to n-hexane in a total volume of 26 ml. The mixture was loaded into a Teflon-lined autoclave of 50 ml capacity under magnetic stirring and then tightly closed. Subsequently, the autoclave was maintained at 180°C for 4 h followed by natural cooling to room temperature. Afterward, the products were centrifugated and washed with absolute ethanol several times. The final products were dried under vacuum at 80°C for 12 h. The HCl concentration was also tuned from 0 to 1.35 M, keeping all other experimental parameters and procedures unchanged.

Characterization

The morphologies of TiO2 samples were investigated by field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) (S-4800, Hitachi, Ltd., Chiyoda, Tokyo, Japan) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (C200, Philips, Germany). The crystal phases of the products were characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD) (PANalytical X'Pert Pro, Holland, The Netherlands), in a 2θ range from 10° to 80°, using Cu Kα radiation. The microstructure of the product was further analyzed using a high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) (Tecnai G2 F-30, FEI Company, Holland, The Netherlands). The diffuse reflectance was performed on a UV-visible (UV–vis) spectrophotometer (TU-1901, Puxi Analytic Instrument Ltd., Beijing, China) using an integrating sphere with an incident angle of 8°. The optical absorption measurement was calculated by transforming the diffuse reflectance data by the program in apparatus. All the samples for diffuse reflectance measurements are powder samples. The Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) surface areas (SBET) of the powder samples were determined by nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherm measurements at 77 K on a Micromeritics TriStar II 3020 nitrogen adsorption apparatus (Micromeritics Instrument Corporation, Norcross, GA, USA). All the samples were degassed at 180°C before the actual measurements.

Photocatalysis tests

The photocatalytic activity tests were carried out by dispersing TiO2 samples in rhodamine B (RhB) solutions and then examining the change of RhB absorbance after UV light irradiation. In a typical procedure, 10 mg TiO2 powder was dispersed in 10 mL RhB aqueous solution with an initial concentration of 10−5 M. This reaction dispersion was magnetically stirred in the dark for 60 min prior to irradiation to establish the adsorption/desorption equilibrium. The TiO2/RhB solution was then exposed to UV light from an 80 W xenon arc lamp with a 420 nm cutoff filter, and the irradiance on the samples is 70 μW cm−2. After illumination, the TiO2 powder was removed from the suspension by centrifugation before the absorption spectrum was taken by a UV–vis spectrophotometer. The photocatalytic activity could be characterized by an apparent first-order rate constant k, which could be calculated using the following equation:

| (1) |

where A0 is the absorbance of the initial RhB solution at 553 nm, and A is the absorbance of RhB at 553 nm when the irradiation time is 5, 10, 15, and 20 min, respectively.

Results and discussion

Effects of acid media on the microstructures of TiO2

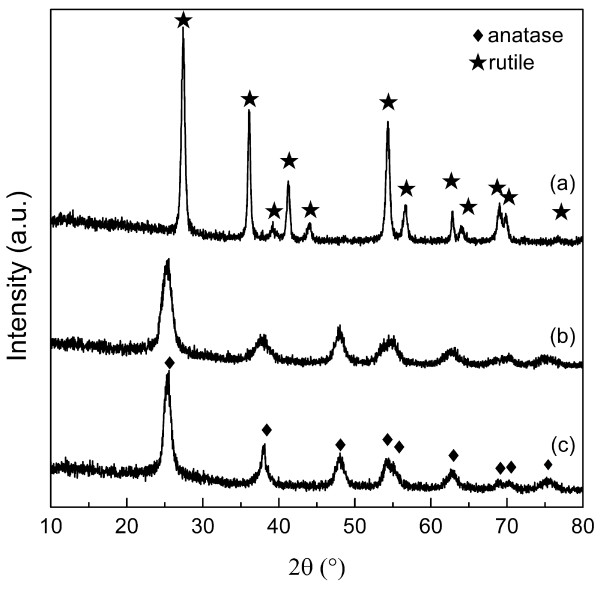

Figure 1 shows the XRD patterns of the products synthesized using HCl, HNO3, and HAc as the acid medium at a fixed concentration of 0.90 M, respectively. Pure rutile (JCPDS no. 21–1276) is formed in HCl medium, while pure anatase (JCPDS no. 21–1272) is generated in both HNO3 and HAc media. The crystal sizes are calculated from either rutile (110) or anatase (101) diffraction using Scherrer's equation [28]. The results show that the estimated crystal sizes of the samples from HCl, HNO3, and HAc medium are 15.4, 5.4, and 8.5 nm, respectively.

Figure 1.

XRD patterns of the products. Products synthesized using various acid media at a concentration of 0.90 M: (a) HCl, (b) HNO3, and (c) HAc.

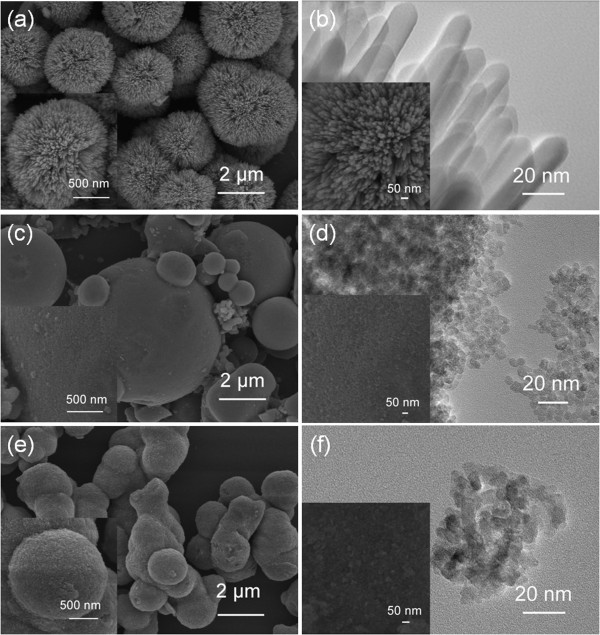

Figure 2 shows the typical FESEM and TEM images of the products synthesized with various acid media at a concentration of 0.90 M. For the sample prepared with HCl, numerous nanorods are highly aggregated into 3D dandelion-like spheres in mean diameter of 2.1 ± 0.2 cm (N = 8, N is the number of measurements) (see Figure 2a and inset), forming a hierarchical structure. Figure 2b and inset show the magnified FESEM and TEM images of the nanorods, indicating that the nanorods possess a rectangular shape with an average diameter of 15.1 ± 1.3 nm (N = 12) and smooth side wall. For the samples derived from either HNO3 or HAc, 3D spheres with a nonuniform size distribution are present (see Figure 2c for HNO3 and Figure 2e for HAc). Magnified TEM and FESEM images of the surfaces (see Figure 2d for HNO3 and Figure 2f for HAc) show that both the spheres are composed of nanoparticles, and the primary particle sizes are about 5.0 ± 0.5 (N = 12) and 8.2 ± 0.9 nm (N = 12), respectively.

Figure 2.

Typical FESEM and TEM images of the products. Products synthesized using various acid media at a concentration of 0.90 M: (a and b) HCl, (c and d) HNO3, and (e and f) HAc. (a), (c), and (e) are overview FESEM images. (b), (d), (f) and the insets are enlarged TEM and FESEM images of the surfaces of the corresponding samples.

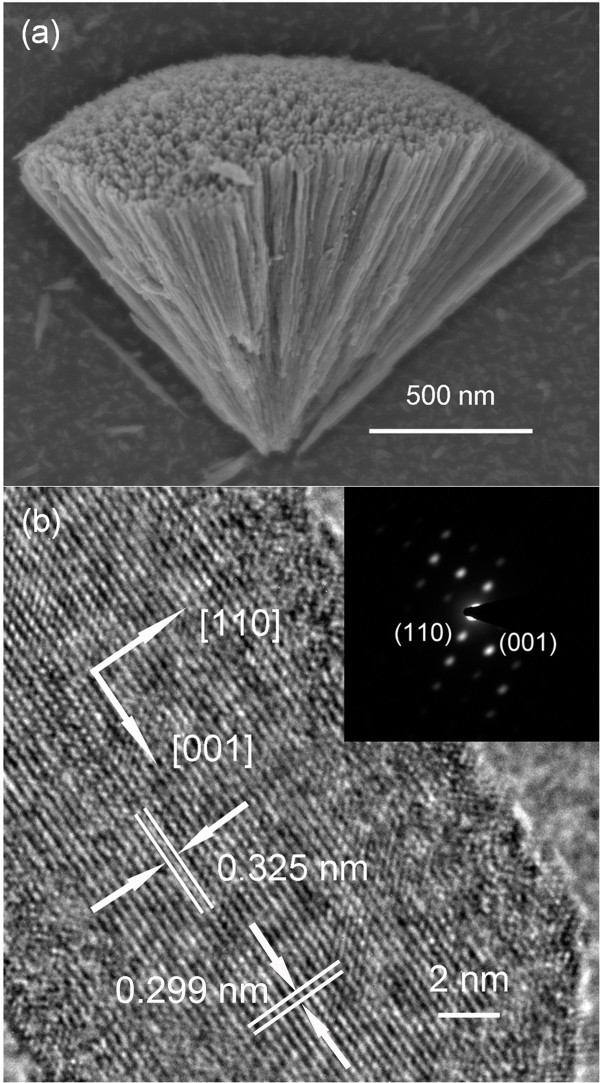

Further characterization of the 3D dandelion-like structure synthesized in 0.90 M HCl medium is provided by the FESEM and HRTEM images shown in Figure 3. The typical section of a sector from a sphere (Figure 3a) confirms that the microsphere is composed of numerous nanorods of about 1 μm in length, radiating from the center to form a spherical dandelion-like structure. In the HRTEM image (Figure 3b), the distances between the adjacent lattice fringes are measured to be 0.325 and 0.299 nm, which agree well with the interplanar distances of rutile TiO2 (110) and (001) (JCPDS no. 21–1276), indicating the growth direction of [001], parallel to c-axis. The corresponding selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern (inset in Figure 3b) demonstrates that the nanorod is single crystalline and could be indexed to the pure rutile TiO2 phase. Combined with the XRD data and HRTEM image, such features imply the single crystal with the exposed surface of (110) crystal plane [29-31].

Figure 3.

FESEM and HRTEM images and corresponding SAED pattern.(a) FESEM image of a sector and (b) HRTEM image and corresponding SAED pattern (inset) of an individual nanorod in the product using HCl acid medium at a concentration of 0.90 M.

The results reveal that the precursor containing HCl as the acid medium has a tendency to form rod-shaped rutile titania, whereas anatase particles are obtained when either HNO3 or HAc is used. The formation of the two different morphologies and crystal structures depends on the presence of diverse ions (Cl−, NO3−, or CH3COOH−) during the synthesis. It is known that anatase nucleates and grows first according to Ostwald's law, and rutile nuclei appears eventually when the successive reaction is taking place since rutile is the thermodynamically most stable phase [16]. Thereafter, rutile quickly grows epitaxially at the expense of mother anatase crystallites via a dissolution and precipitation process [32]. This is also the reason why the crystalline sizes of rutile are always greater than anatase, as shown in Figures 1 and 2.

Both rutile and anatase belong to the tetragonal crystal system, consisting of TiO6 octahedra as a fundamental structural unit. Their crystalline structures differ in the assembly of the octahedral chains [19,33]. Anatase results from face-shared linking of octahedra, while rutile is built by edge-shared linking [34]. Rutile has 42 screw axes along the crystallographic c-axis. The screw structure promotes crystal growth along this direction, resulting in a crystal morphology dominated by the {110} faces [35]. Therefore, rutile nanoparticles are usually rod-like.

The structural rearrangement of octahedral TiO6 units is essential during the phase transformation. It has been known that Cl− anions show weaker affinity to a titanium atom in an aqueous solution than NO3− and CH3COO− anions do [16]. Therefore, pure rutile phase could be obtained in HCl aqueous solution more easily. On the other hand, n-hexane is used as the solvent, which is a nonpolar solvent. The liquid-liquid (nonpolar solvent-water) interface in the present system provides an ideal place for self-assembly of 3D nanostructures [36,37]. In HCl medium, nanorods self-assemble into 3D dandelion-like spheres. Their radial assembly in a good geometrical match to the spherical structure could significantly reduce the total free energy [17]. For both HNO3 and HAc, the strong affinity of NO3− and CH3COO− anions to titanium inhibits the structural rearrangement and, subsequently, the phase transformation [16]. Accordingly, pure anatase is present in both HNO3 and HAc media due to stronger chemical coordination to titanium. Irregular 3D microspheres composed of anatase nanoparticles are obtained in either HNO3 or HAc medium (see Figure 2c,d,e,f).

Effects of hydrochloric acid concentration on the microstructures of TiO2

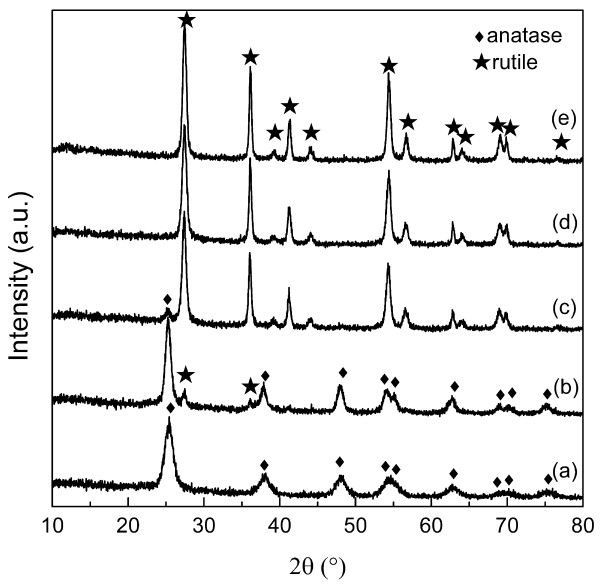

According to the above experimental results with inorganic acid media, it can be concluded that 3D spherical structure composed of rutile nanorods can be formed in HCl. Therefore, HCl solution was selected as a representative acid medium to investigate the growth of 3D dandelion-like structure under various acidity conditions. Figure 4 shows XRD patterns of the products synthesized at various HCl concentrations. Pure anatase (JCPDS no. 21–1272) is formed in the sample without addition of any acids (Figure 4a). At an HCl concentration of 0.45 to 0.68 M, anatase (JCPDS no. 21–1272) and rutile (JCPDS no. 21–1276) coexist in the product (Figure4b,c). The intensity of characteristic peaks of rutile becomes stronger with increasing HCl concentration. Pure rutile (JCPDS no. 21–1276) is obtained when HCl concentration is 1.12 to 1.35 M (Figures 1a and 4d,e). The results indicate that higher HCl concentration favors rutile crystallization. The rutile ratio (χR) of each sample is estimated from XRD intensity data using the formula expressed as follows:

Figure 4.

XRD patterns of the products. Products synthesized at various HCl concentrations: (a) 0, (b) 0.45, (c) 0.68, (d) 1.12, and (e) 1.35 M.

| (2) |

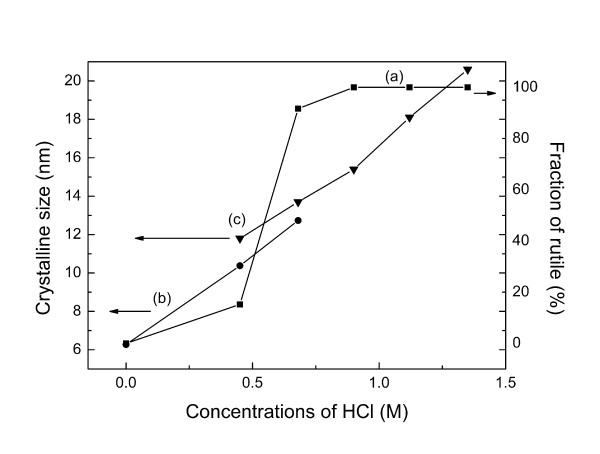

where IA and IR are the integrated intensity of anatase (101) and rutile (110) diffraction peaks, respectively [13,38]. The fraction of rutile tends to be greater at higher HCl concentrations (Figure 5a). Pure rutile phase could be ultimately obtained at an HCl concentration of 0.90 M or higher. The concentration of HCl affects not only the fraction of rutile but also the nanocrystal size in the products. The crystal sizes of the TiO2 samples were determined from the diffraction peak broadening using the Scherrer formula shown in Figure 5b,c. Larger crystalline sizes of either anatase or rutile are obtained at higher HCl concentrations, which can be confirmed by the FESEM and TEM results.

Figure 5.

Influence of HCl concentrations.(a) The fractions of rutile, (b) crystalline sizes of anatase, and (c) crystalline sizes of rutile.

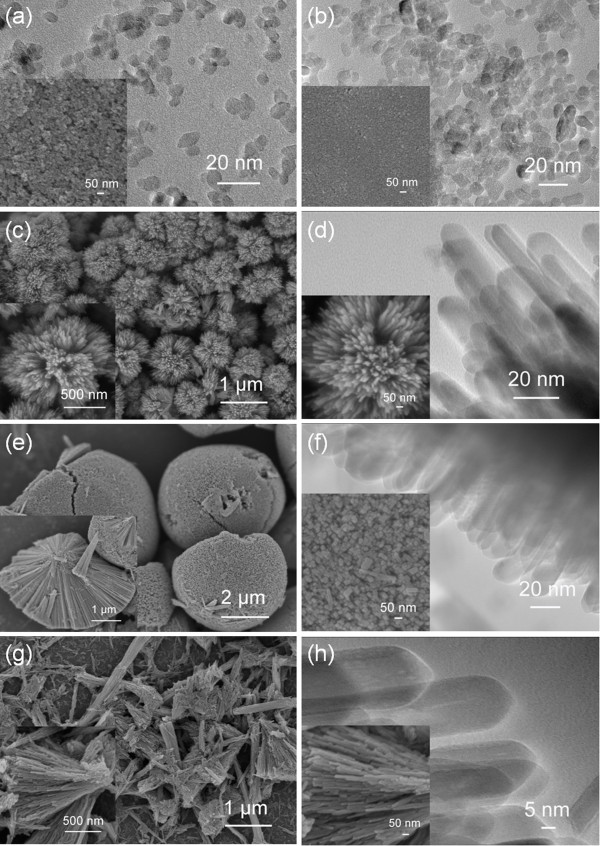

Figure 6 shows the typical FESEM and TEM images of the products synthesized at various HCl concentrations. The samples prepared at HCl concentrations of 0 and 0.45 M assume bulky aggregation of nanoparticles with an average size of 6.1 ± 1.2 (N = 12) and 11.4 ± 0.7 nm (N = 12) (see Figure 6a,b), respectively. At higher HCl concentration (0.68 or 1.12 M), 3D hierarchical dandelion-like spherical structures generate. The mean diameters of the nanorods are 13.5 ± 1.4 (N = 12) and 17.8 ± 1.7 nm (N = 8) at HCl concentrations of 0.68 and 1.12 M (Figure 6d,f), respectively. Meanwhile, together with the sample synthesized with 0.90 M HCl (see Figure 2a,b), it can be found that the rod diameter, rod density, and size of spheres gradually enhance with increasing HCl concentration. The 3D spheres become noticeably not so round when the HCl concentration reaches as high as 1.12 M. Further elevating the HCl concentration to 1.35 M, 3D dandelion-like structures are collapsed into sectors composed of nanorods with an average diameter of 19.8 ± 1.8 nm (N = 5).

Figure 6.

Typical FESEM and TEM images of the products. Products synthesized at various HCl concentrations: (a) 0, (b) 0.45 M, (c and d) 0.68 M, (e and f) 1.12 M and (g and h) 1.35 M. (c), (e), and (g) are overview FESEM images. (d), (f), (h) and the insets are enlarged TEM and FESEM images of the surfaces of the corresponding samples.

It has also been widely reported that higher acid concentration favors the formation of rutile phase since the transformation from anatase to rutile could also be promoted by strong acidity [13,19,35]. In this study, the fraction of rutile enhances with increasing HCl concentration. Bulky aggregated rounded particles are present in the samples of pure anatase or mainly composed of anatase for the low concentration of HCl. When the HCl concentration is 0.68 or higher, rod-like particles are obtained in the sample mainly composed of rutile or pure rutile. Pure rutile is obtained at the HCl concentration of 0.90 M or higher. Acid can accelerate not only phase transformation but also crystal growth [16]. Crystal growth of both anatase and rutile particles can be facilitated in stronger acid solution, respectively. In the present case, either anatase or rutile nanocrystals tend to be larger at higher HCl concentration. Meanwhile, the rod density in the 3D dandelion-like spheres gradually enhances with increasing HCl concentration. Furthermore, both highly acid condition and selectively adsorption of Cl− on rutile (110) plane accelerate the anisotropic growth along [001] orientation [13,35]. Therefore, 3D dandelion-like structures are destroyed when the HCl concentration reaches as high as 1.35 M, resulting in sectors composed of nanorods.

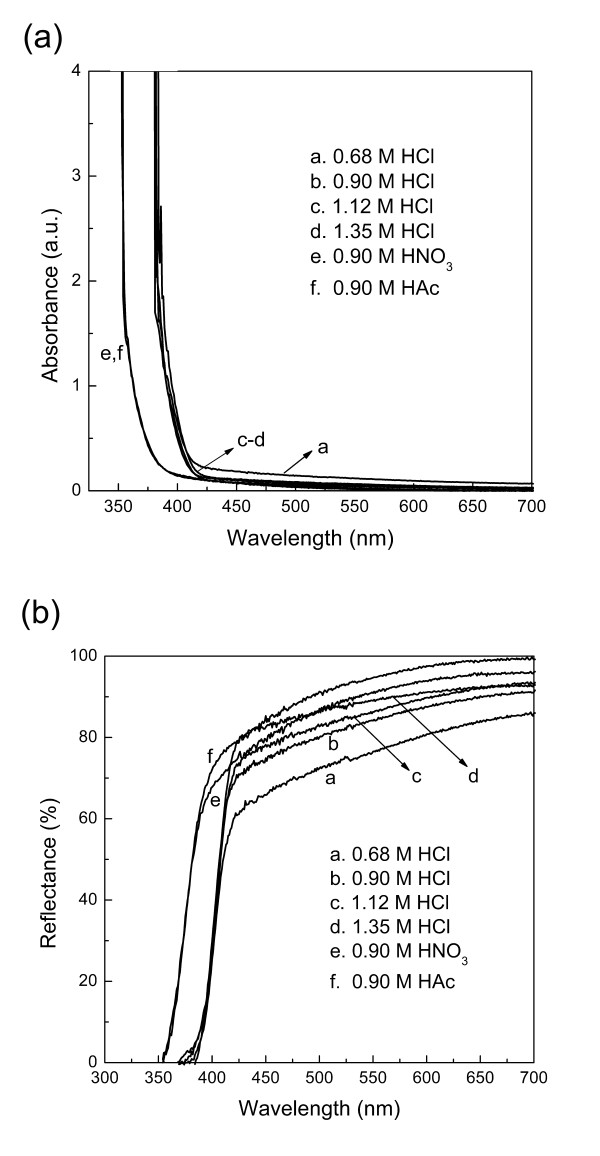

Optical properties of 3D TiO2 structures

The optical absorption and diffuse reflectance spectra of 3D TiO2 structures synthesized with various acid conditions are shown in Figure 7. As seen in Figure 7a, all the samples exhibit low absorption in the visible light range since nanosized TiO2 is a visible-light-transparent material. The slight visible light response for the sample prepared with 0.68 M HCl might be due to the presence of defects in the rutile-anatase mixed structures [39]. The abrupt increase below 400 nm was due to the absorption of light caused by the excitation of electrons from the valence band to the conduction band of TiO2. The absorption edge wavelength of the samples derived from HCl is shorter than that of the samples prepared with either HNO3 or HAc, which can be ascribed to their different crystal phase structures and the narrower band gap of rutile TiO2 (3.0 eV) compared with that of anatase (3.2 eV). The diffuse reflectance spectra shown in Figure 7b also show the red shift in the band gap transition to longer wavelengths for samples prepared with HCl. In UV light region (<420 nm), TiO2 prepared with 0.68, 0.90, or 1.12 M HCl exhibits lower reflectance than that prepared with either HNO3 or HAc. This can be ascribed to the unique 3D dandelion-like structure in which the interspace between ordered rods act as a light-transfer path for introducing incident light into the inner surface of TiO2. This allows UV light waves to penetrate deep inside the TiO2 structure. The nanorods also offer multiple reflective and scattering effects of UV light, preventing the incident waves from bouncing back to the free space [40,41]. Both of these give rise to a lower reflectance and more efficient light harvesting. Among them, TiO2 prepared with 0.68 M HCl shows lowest reflectance since tapered tips are beneficial to lower reflectance in comparison with densely arranged flat tops [41,42]. The increase in reflectance for TiO2 prepared with 1.35 M HCl can be due to the collapse of 3D dandelion-like structure [40].

Figure 7.

Optical absorption (a) and diffuse reflectance spectra (b) of 3D TiO2structures. Structures synthesized with various acid conditions: 0.68 M HCl, 0.90 M HCl, 1.12 M HCl, 1.35 M HCl, 0.90 HNO3, and 0.90 M HAc, respectively.

Photocatalytic activity of 3D TiO2 structures

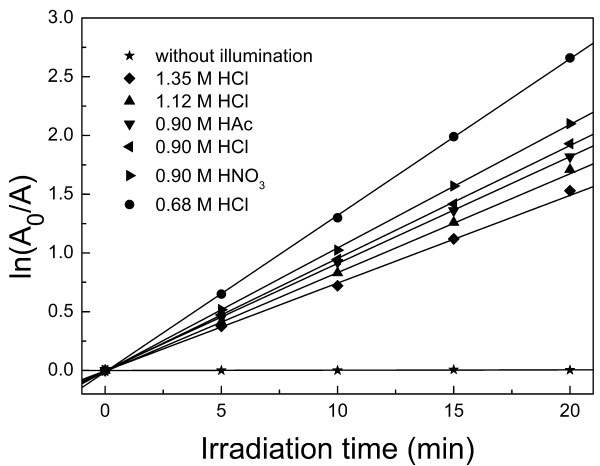

The photocatalytic activity of TiO2 samples can be quantitatively evaluated by comparing the rate constants k, which is calculated by the plots of photocatalytic degradation of RhB as shown in Figure 8. In order to eliminate the influence of adsorption, the typical plot of photocatalytic degradation of RhB without illumination of the TiO2/RhB solution is given in Figure 8. It can be seen that without illumination, the RhB absorptance remains almost unchanged. This assures that the reduction of RhB absorptance comes from the photocatalytic effect of the TiO2 samples rather than powder adsorption. Higher value of k indicates better photocatalytic activity. The k values for the degradation of RhB and BET surface areas are presented in Table 1. It is commonly accepted that mesoporous TiO2 with a large surface area is a superior photocatalyst since a larger surface area provides more active adsorption sites. That is why the sample prepared with HNO3 shows a slightly greater photocatalytic capacity than that with HAc. However, it is difficult to explain the high activity of 3D dandelion-like TiO2 solely based on its surface area. It can be seen that the BET surface area of TiO2 synthesized with HCl is much lower than that with HNO3 or HAc, while the 3D TiO2 prepared with 0.68 or 0.90 M HCl exhibits higher or comparable k value compared with that derived from HNO3 or HAc. Such higher photocatalytic performance than expected can be ascribed to the unique topologies and optical properties of the 3D dandelion-like TiO2. The overall photocatalytic activity is governed by light harvesting efficiency, efficiency of the reaction of photogenerated electron/hole (e−/h+), and the rate of e−/h+ recombination. Firstly, the absorbance is strongly influenced by the topologies of photocatalyst. For 3D dandelion-like TiO2, the interspaces between ordered nanorods serve as a light-transfer path, making it possible to illuminate even the core TiO2 particles. Considering the improved light absorption, reduced reflectance, and scattering within such a hierarchical system, the effective light-activated surface area can be significantly enhanced. This would improve the photoabsorption efficiency of the photocatalyst. On the other hand, only the surface layer contributes to the light harvesting for spheres composed of nanoparticles. Moreover, the oriented 1D geometry provides a direct pathway for photogenerated electron transport, which allows highly efficient photogenerated electron transport through the 3D dandelion-like structure and a lower e−/h+ recombination loss. For nanoparticles, when particle size becomes extremely small, i.e., several nanometers in diameter, surface recombination instead of volume recombination becomes a dominant regime. Most of the e−/h+ are generated sufficiently close to the surface. They may quickly reach the surface and undergo rapid surface recombination mainly due to abundant surface-trapping sites and the lack of driving force for e−/h+ separation. Another reason for the high photocatalytic activity of the sample prepared with 0.68 M HCl might be a mixed phase consisting of rutile and anatase types of TiO2 that prohibits the e−/h+ recombination [43]. For the heterogeneous anatase/rutile TiO2 system, photogenerated electrons are effectively accumulated in the rutile phase without recombining with the holes in the anatase valence band, resulting in the enhancement of the photocatalytic activity. Besides, less aggregation for the dandelion-like morphology facilitates higher photocatalytic activity. As expected, the nanorod fragments fabricated with 1.35 M HCl present lower photocatalytic degradation owing to the collapse of dandelion-like structure as well as severe aggregation and therefore lower surface area.

Figure 8.

Plots of photocatalytic degradation of RhB using 3D TiO2structures. Structures synthesized with various acid conditions: 0.68 M HCl, 0.90 M HCl, 1.12 M HCl, 1.35 M HCl, 0.90 HNO3, and 0.90 M HAc, respectively. The plot ‘without illumination’ represents the typical plot of photocatalytic degradation of RhB without illumination of the TiO2/RhB solution for TiO2 sample prepared with 0.68 M HCl since all the samples show almost the same plot without illumination.

Table 1.

Morphology, BET surface area, and rate constant of products synthesized with various acid conditions

| Acid condition | Unit morphologya | Sizeb(nm) | BET surface area (m2·g−1) | Rate constantk(min−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.68 M HCl |

NR |

13.5 ± 1.4 |

40.3 |

0.135 |

| 0.90 M HCl |

NR |

15.1 ± 1.3 |

38.1 |

0.095 |

| 1.12 M HCl |

NR |

17.8 ± 1.7 |

28.2 |

0.083 |

| 1.35 M HCl |

NR |

19.8 ± 1.8 |

18.7 |

0.074 |

| 0.90 M HNO3 |

NP |

5.0 ± 0.5 |

190.9 |

0.104 |

| 0.90 M HAc | NP | 8.2 ± 0.9 | 153.7 | 0.091 |

aThe morphology of the unit in the hierarchical structure where NR and NP refer to nanorod and nanoparticle, respectively; bthe average diameter of the nanorods or nanoparticles estimated from the FESEM and TEM images.

Conclusions

3D TiO2 hierarchical structures with various microstructures have been successfully synthesized by solvothermal method, in which HCl, HNO3, and HAc is used as the acid medium, respectively. The acid medium significantly affects the microstructures, optical properties, and photocatalytic activity of TiO2. The samples prepared with 0.68 to 1.12 M HCl possessed 3D dandelion-like spheres assembled of radially arranged rutile nanorods. Both the fraction of rutile and the diameter of nanorod are enhanced with the increasing HCl concentration. For the products derived from either HNO3 or HAc, 3D spheres composed of anatase nanoparticles were present. The unique 3D dandelion-like hierarchical structure exhibited low reflectance and efficient light harvesting since the ordered rods provided a light-transfer path for incident light and multiple reflective and scattering effects. 3D TiO2 prepared with 0.68 M HCl showed superior photocatalytic activity due to this unique topology and optical properties as well as anatase/rutile heterogeneous system. Considering the unique morphology of the 3D dandelion-like TiO2 structures, the recovery of these 3D TiO2 powders from the solution is believed to be much easier than that of nanoparticle powders.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

JZ participated in the design of the study, carried out the experiments, collected data, performed data analysis, and drafted the manuscript. GZ, BS, and GH participated in the design of the study, discussion of data, and helped to draft the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Jing Zhou, Email: zhoujing0205@zju.edu.cn.

Bin Song, Email: bzsong@zju.edu.cn.

Gaoling Zhao, Email: glzhao@zju.edu.cn.

Gaorong Han, Email: hgr@zju.edu.cn.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51172201) and National "Twelfth Five-Year" Plan for Science & Technology Support, (2011BAE14B02).

References

- Oregan B, Gratzel M. A low-cost, high-efficiency solar-cell based on dye-sensitized colloidal TiO2films. Nature. 1991;353:737–740. doi: 10.1038/353737a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Asahi R, Morikawa T, Ohwaki T, Aoki K, Taga Y. Visible-light photocatalysis in nitrogen-doped titanium oxides. Science. 2001;293:269–271. doi: 10.1126/science.1061051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colomer MT. Nanoporuous anatase thin films as fast proton-conducting materials. Adv Mater. 2006;18:371–374. doi: 10.1002/adma.200500689. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Colomer MT, Maczka M. Mixed conductivity, structural and microstructural characterization of titania-doped yttria tetragonal zirconia polycrystalline/titania-doped yttria stabilized zirconia composite anode matrices. J Solid State Chem. 2011;184:365–372. doi: 10.1016/j.jssc.2010.12.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yeredla RR, Xu HF. Incorporating strong polarity minerals of tourmaline with semiconductor titania to improve the photosplitting of water. J Phys Chem C. 2008;112:532–539. doi: 10.1021/jp076824l. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ali G, Chen C, Yoo SH, Kum JM, Cho SO. Fabrication of complete titania nanoporous structures via electrochemical anodization of Ti. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2011;6:332. doi: 10.1186/1556-276X-6-332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao CB, Zhang GS, Song XP, Sun ZQ. Morphology and microstructure of As-synthesized anodic TiO(2) nanotube arrays. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2011;6:64. doi: 10.1007/s11671-010-9812-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontos AG, Likodimos V, Vassalou E, Kapogianni I, Raptis YS, Raptis C, Falaras P. Nanostructured titania films sensitized by quantum dot chalcogenides. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2011;6:266. doi: 10.1186/1556-276X-6-266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu W, Xiao XH, Zhang SF, Ren F, Jiang CZ. Facile method to synthesize magnetic iron oxides/TiO(2) hybrid nanoparticles and their photodegradation application of methylene blue. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2011;6:533. doi: 10.1186/1556-276X-6-533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burda C, Chen XB, Narayanan R, El-Sayed MA. Chemistry and properties of nanocrystals of different shapes. Chem Rev. 2005;105:1025–1102. doi: 10.1021/cr030063a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahu M, Biswas P. Single-step processing of copper-doped titania nanomaterials in a flame aerosol reactor. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2011;6:1–14. doi: 10.1186/1556-276X-6-441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witharana S, Chen HS, Ding YL. Stability of nanofluids in quiescent and shear flow fields. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2011;6:231. doi: 10.1186/1556-276X-6-231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li HB, Duan XC, Liu GC, Jia XB, Liu XQ. Morphology controllable synthesis of TiO2by a facile hydrothermal process. Mater Lett. 2008;62:4035–4037. doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2008.05.056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Mao SS. Titanium dioxide nanomaterials: synthesis, properties, modifications, and applications. Chem Rev. 2007;107:2891–2959. doi: 10.1021/cr0500535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suttiponparnit K, Jiang JK, Sahu M, Suvachittanont S, Charinpanitkul T, Biswas P. Role of surface area, primary particle size, and crystal phase on titanium dioxide nanoparticle dispersion properties. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2011;6:27. doi: 10.1007/s11671-010-9772-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu MM, Lin G, Chen DH, Wang GG, He D, Feng SH, Xu RR. Sol-hydrothermal synthesis and hydrothermally structural evolution of nanocrystal titanium dioxide. Chem Mater. 2002;14:1974–1980. doi: 10.1021/cm0102739. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang XF, Konishi H, Xu HF, Wu MM. Comparative sol-hydro(solvo)thermal synthesis of TiO2nanocrystals. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2006;2006:2229–2235. doi: 10.1002/ejic.200500855. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson M, Osterlund L, Ljungstrom S, Palmqvist A. Preparation of nanosize anatase and rutile TiO2by hydrothermal treatment of microemulsions and their activity for photocatalytic wet oxidation of phenol. J Phys Chem B. 2002;106:10674–10679. doi: 10.1021/jp025715y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CC, Ying JY. Sol–gel synthesis and hydrothermal processing of anatase and rutile titania nanocrystals. Chem Mater. 1999;11:3113–3120. doi: 10.1021/cm990180f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu WB, Li LP, Tong WM, Li GS, Yan TJ. Tailoring the nanoscale boundary cavities in rutile TiO(2) hierarchical microspheres for giant dielectric performance. J Mater Chem. 2010;20:8659–8667. doi: 10.1039/c0jm01232g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoffe AD. Low-dimensional systems: quantum size effects and electronic properties of semiconductor microcrystallites (zero-dimensional systems) and some quasi-two-dimensional systems. Adv Phys. 2002;51:799–890. doi: 10.1080/00018730110117451. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bal XL, Xie B, Pan N, Wang XP, Wang HQ. Novel three-dimensional dandelion-like TiO2structure with high photocatalytic activity. J Solid State Chem. 2008;181:450–456. doi: 10.1016/j.jssc.2007.12.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Zhao YP, Liu HJ, Kou HZ, Wang YQ. Directed growth of TiO2nanorods into microspheres. Nanotechnology. 2006;17:5046–5050. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/17/20/003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang SW, Gao L. Fabrication and shape-evolution of nanostructured TiO2via a sol-solvothermal process based on benzene-water interfaces. Mater Chem Phys. 2006;99:437–440. doi: 10.1016/j.matchemphys.2005.11.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luo JQ, Gao L. Large-scale production of monodispersed titania microspheres by surfactant-guided self-assembly. J Alloys Compd. 2009;487:763–767. doi: 10.1016/j.jallcom.2009.08.067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu HB, Chen JS, Lou XW, Hng HH. Asymmetric anatase TiO(2) nanocrystals with exposed high-index facets and their excellent lithium storage properties. Nanoscale. 2011;3:4082–4084. doi: 10.1039/c1nr10854a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Zhao GL, Song B, Han GR. Solvent-controlled synthesis of TiO2 three-dimensional nanostructures via a one-step solvothermal route. CrytsEngComm. 2011;13:2294–2302. doi: 10.1039/c0ce00793e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cullity BD. Elements of X-Ray Diffraction. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang HB, Cuan QA, Wen CZ, Xing J, Wu D, Gong XQ, Li CZ, Yang HG. Anatase TiO(2) crystals with exposed high-index facets. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2011;50:3764–3768. doi: 10.1002/anie.201007771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosono E, Fujihara S, Kakiuchi K, Imai H. Growth of submicrometer-scale rectangular parallelepiped rutile TiO2films in aqueous TiCl3solutions under hydrothermal conditions. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:7790–7791. doi: 10.1021/ja048820p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng XJ, Zhai J, Jiang L. The fabrication and switchable superhydrophobicity of TiO2nanorod films. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2005;44:5115–5118. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penn RL, Banfield JF. Formation of rutile nuclei at anatase 112 twin interfaces and the phase transformation mechanism in nanocrystalline titania. Am Mineral. 1999;84:871–876. [Google Scholar]

- Li YY, Liu JP, Jia ZJ. Morphological control and photodegradation behavior of rutile TiO2prepared by a low-temperature process. Mater Lett. 2006;60:1753–1757. doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2005.12.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagisawa K, Ovenstone J. Crystallization of anatase from amorphous titania using the hydrothermal technique: effects of starting material and temperature. J Phys Chem B. 1999;103:7781–7787. doi: 10.1021/jp990521c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li JG, Ishigaki T, Sun XD. Anatase, brookite, and rutile nanocrystals via redox reactions under mild hydrothermal conditions: phase-selective synthesis and physicochemical properties. J Phys Chem C. 2007;111:4969–4976. doi: 10.1021/jp0673258. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y, Skaff H, Emrick T, Dinsmore AD, Russell TP. Nanoparticle assembly and transport at liquid-liquid interfaces. Science. 2003;299:226–229. doi: 10.1126/science.1078616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velev OD, Furusawa K, Nagayama K. Assembly of latex particles by using emulsion droplets as templates .1. Microstructured hollow spheres. Langmuir. 1996;12:2374–2384. doi: 10.1021/la9506786. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sreethawong T, Suzuki Y, Yoshikawa S. Photocatalytic evolution of hydrogen over nanocrystalline mesoporous titania prepared by surfactant-assisted templating sol–gel process. Catal Commun. 2005;6:119–124. doi: 10.1016/j.catcom.2004.11.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen XB, Liu L, Yu PY, Mao SS. Increasing solar absorption for photocatalysis with black hydrogenated titanium dioxide nanocrystals. Science. 2011;331:746–750. doi: 10.1126/science.1200448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian GH, Chen YJ, Zhou W, Pan K, Tian CG, Huang XR, Fu HG. 3D hierarchical flower-like TiO(2) nanostructure: morphology control and its photocatalytic property. CrystEngComm. 2011;13:2994–3000. doi: 10.1039/c0ce00851f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh LK, Lai KY, Lin GJ, Fu PH, Chang HC, Lin CA, He JH. Giant efficiency enhancement of GaAs solar cells with graded antireflection layers based on syringelike ZnO nanorod arrays. Adv Energy Mater. 2011;1:506–510. doi: 10.1002/aenm.201100025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diedenhofen SL, Vecchi G, Algra RE, Hartsuiker A, Muskens OL, Immink G, Bakkers EPAM, Vos WL, Rivas JG. Broad-band and omnidirectional antireflection coatings based on semiconductor nanorods. Adv Mater. 2009;21:973–978. doi: 10.1002/adma.200802767. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jia JG, Ohno T, Matsumura M. Efficient dihydroxylation of naphthalene on photoirradiated rutile TiO2powder in solution containing hydrogen peroxide. Chem Lett. 2000. pp. 908–909.