Abstract

Platelet-activating factor (PAF) is a bioactive lipid mediator with strong inflammatory properties. PAF induces the expression and activation of metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) in corneal epithelial cells and myofibroblasts, and delays epithelial wound healing in an organ culture system. Lipoxin A4 (LXA4) is a lipid mediator involved in resolution of inflammation and cornea epithelial wound healing. We developed an in vivo mouse model of injury to the anterior stroma that is sustained by PAF and evaluated the action of LXA4. In this model mice were treated with vehicle, PAF alone and in combination with PAF receptor antagonist LAU-0901 or LXA4. Mice were euthanized 1, 2 and 7 days after injury and corneas were processed for histology (H&E staining) and immunofluorescence with antibodies for MMP-9, α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), fibronectin (FN) and neutrophil. Interleukin 1-α (IL-1α) and keratinocyte-derived chemokine (KC/CXCL1) were assayed by ELISA. Myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity was performed in corneal homogenates. In this in vivo model PAF inhibited epithelial wound healing that was blocked by the PAF receptor antagonist LAU-0901. Treatment with LXA4 significantly reduced the injured area compared to PAF at 1 and 2 days of treatment. The strong stromal cell infiltration and MPO activity stimulated by PAF was also decreased with LXA4 treatment. PAF increased MMP-9 and decreased FN expression compared to vehicle treatment and less α-SMA positive cells migrated to the wounded area. The PAF actions were reverted by LXA4 treatment. The results demonstrated a powerful action of LXA4 in protecting corneas with injuries that compromise the stroma by decreasing inflammation and increasing wound healing.

Keywords: Lipoxin A4, platelet-activating factor, corneal inflammation, corneal wound healing, metalloproteinase-9, fibronectin, alpha-smooth muscle actin, neutrophil infiltration

1. Introduction

Inflammation is an early response to corneal damage and an integral part of wound healing. Sustained corneal inflammation, however, may lead to opacity, ulceration, stromal melting and tissue destruction (Bazan, 2005; Kenchegowda and Bazan, 2010). To prevent such complications, corneal wounds must be re-epithelialized as quickly as possible.

Corneal injury activates the release of arachidonic acid (AA) and the formation of biologically active lipids, including prostaglandins, lipoxygenase derivatives and the potent phospholipid mediator platelet-activating factor (PAF), which is involved in the inflammatory response (Bazan, 1987, 1989; Bazan et al., 1985, 1991; Hurst et al., 1991). PAF exerts its effects through activation of a G-protein-coupled PAF receptor (PAF-R) that generates several biochemical reactions associated with inflammation, wound healing and apoptosis (Bazan and Ottino, 2000). In addition, injury increases the expression of the PAF-receptor producing a feed-back reaction that exacerbates the inflammatory reaction (Ma and Bazan, 2000). Previous studies have shown that PAF induces the expression and activation of selective metalloproteinases (MMPs) in both epithelial cells and stromal myofibroblasts (Bazan et al., 1993; Ottino et al., 2005; Tao et al., 1995). MMPs are important enzymes involved in the degradation and remodeling of components of the extracellular matrix (ECM); their action is fundamental for the wound healing process, but over-activation can cause tissue damage. Due to the fundamental role of MMPs their activation is tightly regulated, mainly by tissue inhibitors of MMPs (TIMPs). MMP-9 is one of the main MMPs activated by PAF, due to a PAF-induced imbalance favoring the stimulation of MMP-9 and not TIMP-1 and-2 (Ottino et al., 2002). Excessive expression of MMP-9 is associated with tissue damage and ulceration (Pflugfelder et al., 2005; Rayment and Upton, 2009; Yager and Nwomeh, 1999). In fact, using an organ tissue model we have previously reported that PAF inhibits wound closure and induces keratocyte apoptosis (Chandrasekher et al., 2002). In addition, blocking the PAF receptor protects rabbit corneas from perforation after an in vivo alkali burn model (He et al., 2006). In that experiment, we noticed that using a very specific PAF-receptor antagonist, LAU-0901, there was an increase in fibronectin (FN) released in the limbal area where myofibroblasts derived from activated keratocytes after stromal damage were expressed (unpublished). Fibronectin is a substrate of MMP-9 (Marom et al., 2007; Opdenakker et al., 2001) and provides a temporary matrix that acts as a framework for cell adhesion and migration after injury. This matrix allows for the connection of myofibroblasts to other extracellular matrix (ECM) components such as collagen and glycosaminoglycans (Jester and Ho-Chang 2003). Accordingly, decreased availability of FN disrupts migration and contraction and impairs wound healing (Ishizaki et al., 1997; Phan et al., 1989).

Lipoxin A4 (LXA4), a lipoxygenase derivative of AA with anti-inflammatory properties (Bannenberg and Serhan, 2010; Chiang et al., 2005), is an intermediate in the reparative action of epidermal growth factor in cornea wound healing (Kenchegowda et al., 2011) and stimulates epithelial and endothelial proliferation (Gronert et al., 2005; He et al.,2011). Because both PAF and LXA4 biosynthesis increases after corneal injury (Bazan et al., 1991; Gronert et al., 2005) and is not known if there is interaction between these lipid mediators in cellular injury and repair, we propose to test the hypothesis that while PAF plays a key role in contributing to tissue destruction, LXA4 counter arrests the action of PAF in order to maintain homeostasis.

For these studies, we use an in vivo model of injury to the epithelium and anterior stroma allowing the appearance of myofibroblasts whose major roles are to reconstitute the ECM and promote wound healing. This model allows us to investigate the interaction of PAF and LXA4 during the corneal wound healing response.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and cells

Mice were treated in compliance with the guidelines of the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research, and the experimental protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, Louisiana State University Health Science Center. Male C57BL/6 mice 5-7 weeks old were purchased from Charles River (Wilmington, MA). Rabbit eyes were from Pel-Freez Biologicals (Rogers, AR).

2.2. Antibodies, Lipids and Other Materials

cPAF [1-o-hexadecyl-2-o-(N-methylcarbamyl)-sn-glyceryl-3-phosphorylcholine, a stable analog of PAF] and LXA4 [5S,6R,15S-trihydroxy-eicosa-7E,9E,11Z,13E-tetraenoic acid] were purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). LAU-0901 [2, 4, 6-trimethyl-1,4-dihydropyridine-3,5 dicarboxyacid ester] was a gift from Dr. Nicolas Bazan (Neuroscience Center of Excellence, LSUHSC, New Orleans, LA). Rabbit polyclonal antibodies for alpha smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), FN, MMP-9 and rat monoclonal antibody clone number 7/4 to neutrophil were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). The Quantikine Mouse interleukin-1α (IL-1α) and keratinocyte-derived chemokine (KC) Immunoassay Elisa kits were from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). The secondary antibodies goat anti-rat Alexa Fluor 488 and goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488, Novex zymogram gels containing 10% gelatin, and zymogram buffers were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Hematoxylin and eosin solutions, hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide (HTAB), o-dianisidine dihydrochloride, protease inhibitors, DAPI (4′-6′-diamidino-2 phenylindole), goat serum and methylene blue were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). DMEM/F12 was from Gibco (Grand Island, NY), and filters to concentrate media for zymography were from Millipore (Billerica, MA).

2.3. In Vivo Corneal Injury Model and Treatment

Male C57BL/6 mice were anesthetized with ketamine (200 mg/Kg) and xylazine (10 mg/Kg) intramuscularly, and a drop of tetracaine-HCl 0.5% was applied to the right eye subjected to injury. The epithelium and the anterior stroma (about 25%) was removed up to the limbal border under a surgical microscope using a corneal rust ring remover with a 0.5 mm burr (Algerbrush II, Alger Company, Lago Vista, TX).

The mice were randomly divided in four groups after injury. In the first group, the eye was treated topically with cPAF (10 μg/ml, 2 × 5 μl). The second group received LAU-0901 (30 mg/Kg dissolved in water) injected intraperitoneally after cPAF application; this group served as a control for PAF action. Both LAU-0901 injection and cPAF treatment took place once a day. The third group was treated with cPAF once a day and with LXA4 (1 μg/ eye in 10 μl PBS) applied topically in two doses of 5 μl each 3 times/day. This dose had been shown to stimulate wound healing in mouse corneas (Gronert et al., 2005). The fourth group received only vehicle (0.1% ethanol in PBS). The left eyes of this group was not injured or given treatments, and were processed as normal controls. Six to eight mice were used per condition and the experiment was repeated 3 times. The mice were sacrificed at 1, 2, and 7 days after injury.

2.4. Corneal wound healing evaluation

At each time point the mice were euthanized and the eyes immediately enucleated. The corneas were stained with 0.5 % methylene blue for 1 min and then washed with PBS for 2 min; the area of the cornea not covered by epithelium was stained in blue. Photographs were taken with a dissecting microscope (Nikon SMZ- 1500) through an attached digital camera (Nikon DXM 1200). The images were analyzed utilizing Adobe Photoshop software.

2.5. Histological and Immunofluorescence staining

The enucleated eyes were washed with PBS and fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde for 24 hours at 4°C, then embedded in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound (Sakura Finetek USA, Torrance, CA) and stored at −80°C. Serial 6-um cryostat sections were cut, mounted on microscope slides (Superfrost Plus, Fisher Scientific), air-dried, and stored at −20 °C until use. For histological evaluations the slides were stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For immunofluorescence staining the corneal section were thoroughly washed in PBS, blocked with 10 % goat serum, 0.1 % Triton X-100 in PBS for 30 min at room temperature, then incubated overnight at 4°C with the different primary antibodies against myeloperoxidase (MPO), FN, α-SMA, MMP-9 and neutrophil. Afterward, the sections were incubated with their respective secondary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature. After each step, the samples were washed with PBS. DAPI staining was performed to localize the nuclei. The sections were examined with a Nikon fluorescence microscope Eclipse TE 200 (Tokyo, Japan) under 200x magnification, and the images captured with a Photometric camera (Cool Snap HQ; Tucson, AZ).

2.6. Quantification of α-SMA positive cells

To quantify the myofibroblasts, six corneal sections from 3 different corneas/conditions were immunostained with anti-α-SMA antibody and the α-SMA positive cells were counted in four randomly selected fields. Images were captured as explained above (2.5.).

2.7. Myeloperoxidase activity assay

To quantify polymorphonuclear neutrophiles (PMNs) the MPO activity was assayed by the method of Bradley et al. (1982a). In brief, corneas were homogenized in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6) containing 0.5% HTAB using a tissue grinder with glass pestle to produce uniform homogenate. The homogenates were subjected to three cycles of sonication and freeze-thaw to release MPO from the azurophilic granules, and then centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. The MPO activity in the supernatant was assayed spectrophotometrically by following the increase in absorbance at 460 nm. The reaction mixture contained 0.0005% hydrogen peroxide and 0.167 mg/ml o-dianisidine hydrochloride. The increment of absorbance was recorded every 30 seconds for 5 min. The enzymatic activity, calculated in the linear part of the reaction, was expressed as optical density (OD)/ min/ cornea.

2.8. Cytokine assay

Corneas were homogenized with PBS buffer containing 1% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitors in a ratio 100μl/cornea using a tissue grinder with a glass pestle, then sonicated for 10 seconds and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. IL-1α and KC were measured in the supernatant using a Quantikine Mouse IL-1α (or KC) Immunoassay ELISA Kit following their protocol. Concentration of IL-1α or KC was expressed in pg/cornea.

2.9. Organ culture and Zymography

Rabbit eyes were shipped to the laboratory on ice in Hanks solution containing antibiotics and antimycotics. Corneas (three/condition) were dissected to include a scleral rim and placed on Teflon balls as previously described (Chandrasekher et al., 2002). Corneas were stimulated with cPAF (100nM), LXA4 (100nM) or cPAF + LXA4 for 16 hours in 5 ml of DEME/F12; controls were non stimulated corneas.

2 ml of media was concentrated to 50 μl, and 20 μl aliquots were diluted (1:1) with zymogram sample buffer and electrophoresed with a running buffer using 10% gelatin zymogram gels for 90 min at 125 V. The gels were incubated for 1 hour at room temperature in zymogram renaturation buffer, followed by incubation overnight with zymogram development buffer. Gels were stained with Coomassie blue, and the position of a clear band corresponding to active MMP-9 was visualized against a uniformly dark-stained background.

2.10. Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The data was analyzed by ANOVA to compare the different groups and considered significant with a p<0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Action of PAF, PAF-R antagonist and LXA4 in epithelial wound healing in vivo

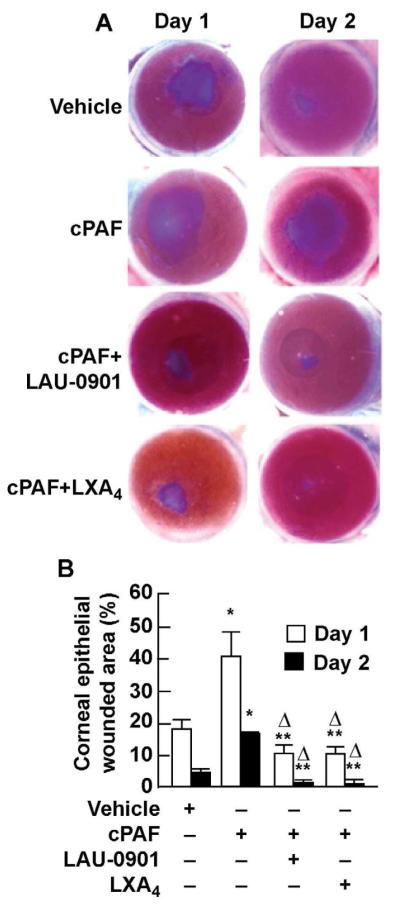

We developed an in vivo mouse model of epithelial and stromal injury to allow the expression of α-SMA positive cells. In this model, cPAF was added once a day to obtain an amplified and sustained inflammatory response. To evaluate the progress of epithelial wound closure the corneas were stained with methylene blue (Fig. 1A). cPAF significantly delayed epithelial wound healing. On day 1 after the injury 40 % of the total wounded area was not covered; at day 2 18 % of the injury area remained uncovered (Fig.1B). Treatment with the PAF-R antagonist LAU-0901 significantly blocked the action of cPAF (Fig. 1A and 1B) demonstrating that the action of PAF is through receptor activation. When the mouse corneas were treated with LXA4 the effect of PAF was also blocked. On day 1 after injury, treatment with LXA4 decreased the injured area to about 10 %, while at day 2 the epithelial healing was almost complete. At day 7, the epithelial closure was complete regardless of treatment (data not shown).

Figure 1. Effect of cPAF, LAU-0901 and LXA4in mouse corneal epithelial wound healing in vivo.

A) After injury, corneas were treated with cPAF alone or in conjunction with LAU-0901, or LXA4 for 1 or 2 days as explained in Methods (2.3.). Corneas were stained at each time point with methylene blue. The data in B) represent the percentage (average ± SD) of the remaining wounded area of 4 corneas per condition. (*) significant increase of injured area by cPAF respect to vehicle; (**) significant decrease in the injured area compare to cPAF treatment; (Δ) significant increase in epithelial wound healing when compare to vehicle.

3.2. LAU-0901 and LXA4 effect on PAF-induced inflammatory response

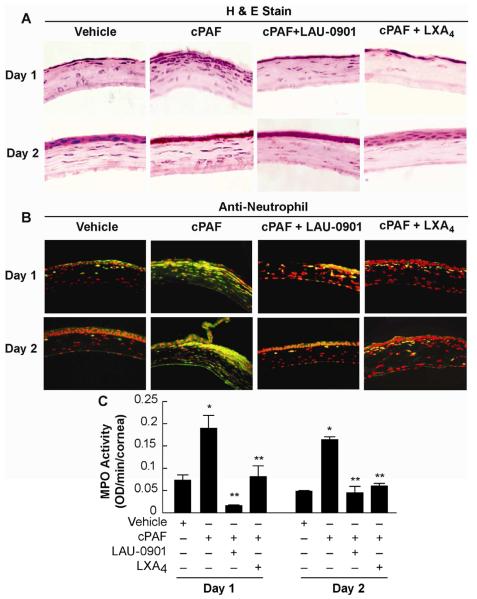

Corneal sections stained with H&E showed numerous inflammatory cells in the stroma on days 1 and 2 after injury (Fig. 2A). The number of infiltrating cells increased in the presence of cPAF, and 1 week after treatment the corneas were still inflamed (data not shown). The effect of PAF was inhibited when mice were treated with LAU-0901 or LXA4, showing the corneas’ mild hypercellularity. To determine if PMNs were infiltrating the tissue, corneal sections were immunostained with anti-neutrophil antibody (Fig. 2B). A significant increase in PMNs was observed when the eyes were treated with cPAF for 1 or 2 days after corneal wound; both LAU 0901 and LXA4 blocked the action of PAF with significantly less PMNs infiltration.

Figure 2. PMNs infiltration after cPAF, LAU-0901 and LXA4 treatments.

A) Cornea sections stained with H&E show increased infiltration of inflammatory cells in the stroma when the mice were treated with cPAF once a day for 1 or 2 days. Treatment with LAU-0901 or LXA4 blocked the action of PAF. B) Corneal sections were immunostained with anti-neutrophil antibody (dilution 1:100) showing neutrophil cells in green. DAPI was used to counter stain the nuclei (red). C) MPO activity was assayed as explained in Methods (2.7.) in the supernatant of corneal homogenates. The data is representative of quadruplicate activity assays of two independent experiments and is expressed as optical density (OD) / minute/ cornea.

Since MPO is a well-established marker of neutrophil infiltration (Bradley et al., 1982b), we evaluated the MPO activity in corneas treated with cPAF alone or in combination with LAU-0901 or LXA4 after injury (Fig. 2C). cPAF increased the MPO activity 2.6 - 3 times compared with vehicle; this activity was significantly decreased in mice treated with LAU-0901 or LXA4 for 1 or 2 days after the injury. The data demonstrate that both LAU-0901 and LXA4 inhibit the PAF-induced PMN infiltration.

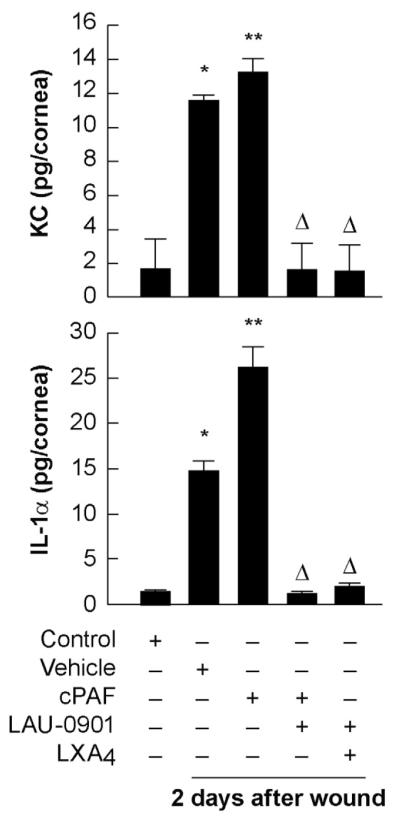

3.3. Expression of KC and IL-1α in the mouse corneas treated with PAF, and action of LAU-0901 and LXA4

To determine the effect of PAF on inflammatory components after injury in corneas treated for 2 days with cPAF with or without the PAF antagonist LAU-0901 or LXA4, mouse corneas were analyzed by ELISA for the expression of the chemokine KC and the cytokine IL-1α (Fig. 3). Injury stimulates the expression, increasing the synthesis of KC by 6 times and 7.5 times for IL-1α expression. Topical treatment with cPAF once a day further increases the expression of these inflammatory compounds. Expression of IL-1α was near twice as high than with vehicle. These values are consistent with an exacerbated inflammatory response when cPAF is added. Additional treatments with LAU-0901 or LXA4 completely abolish the expression of KC and IL-1α.

Figure 3. Action of LXA4 and PAF antagonist on IL-1α and KC expression.

Injured mice corneas with the different treatments were homogenized and the supernatant was analyzed for KC and IL-1α using the ELISA kits as explained in Methods (2.8.). Controls are uninjured corneas. The results were expressed in picograms per cornea (pg/cornea). The assays were carried out in duplicate and the data represent the average of two different experiments. (*) indicates significant difference respect to uninjured corneas; (**) indicates significant difference with respect to vehicle. () indicates significant differences respect to PAF treatment alone.

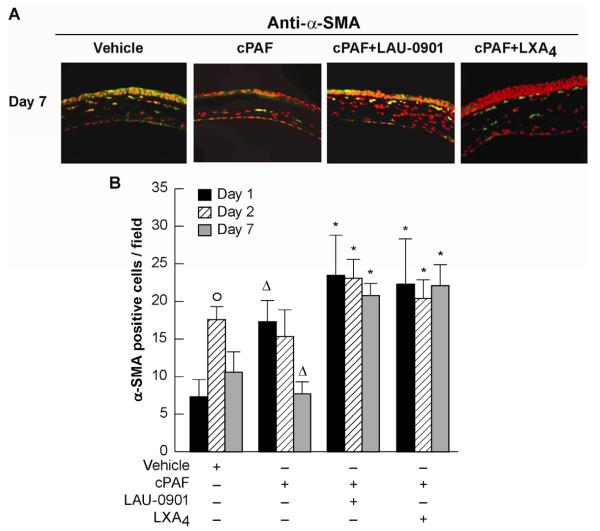

3.4. LAU-0901 and LXA4 effect on α-SMA positive cells in the central cornea

After injury, quiescent keratocytes outside the injury area become metabolically activated and differentiate to a myofibroblast phenotype, characterized by the expression of α-SMA (Fini, 1999). Myofibroblasts then migrate to the damaged area and proliferate. The presence of myofibroblasts was increased in corneas treated with cPAF+LAU-0901 or cPAF + LXA4 for 7 days after injury compared with cPAF alone (Fig. 4A). Quantification of α-SMA positive cells in the central cornea at days 1, 2 and 7 after injury and treatments (Fig. 4B) shows significant increases on day 2 after injury in the vehicle treated corneas that were decreased after 7 days. cPAF increases α-SMA staining in the central stroma at day 1 after the injury however, and by day 7 treatment with cPAF shows a decrease that was significant (p=0.02) when compared to vehicle treated corneas. Corneas treated with LAU-0901 or LXA4 in the presence of cPAF showed significant increase in α-SMA positive cells at 1 and 2 days that were maintained by day 7. No significant differences in α-SMA staining were found in the limbal area (data not shown). The data suggests that PAF diminished the appearance of myofibroblasts in the central cornea.

Figure 4. Appearance of α-SMA positive cells in the central cornea.

Alpha-SMA was used as a marker for myofibroblasts. A) Corneal sections from day 7 after injury; and treatments were immunostained with anti-α-SMA rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:500 dilution) and counterstained with DAPI (red). B) The α-SMA positive cells were counted at day 1, 2 and 7 after the injury as explained in Methods (2.6.). (°) significant increase of α-SMA positive cells compare to day 1 after injury; () significant differences respect to vehicle; (*) significant increase in α-SMA positive cells compare to cPAF treatment.

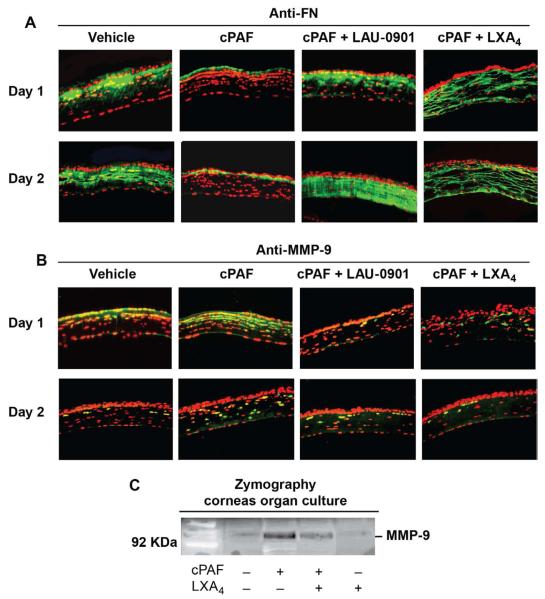

3.5. PAF action on fibronectin (FN) and metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) expression

The major roles of myofibroblasts include reconstituting the collagen-rich ECM and promoting wound closure by contraction (Fini, 1999; Fini and Stramer, 2005). FN is a glycoprotein secreted by cells that is poorly expressed in normal tissue but is expressed during wound healing, favoring adhesion and migration of myofibroblasts. We then investigated how PAF affected FN expression in the mouse model (Fig. 5A). Immunostaining demonstrated a strong expression of FN in the stroma that was significantly decreased when the corneas were treated with cPAF for 1 and 2 days. A similar trend was observed at 7 days (not shown). When corneas were treated with the PAF antagonist LAU-0901 or with LXA4 in the presence of cPAF there was a strong upregulation of FN expression in the stroma. We have previously shown that PAF is a strong inducer of MMP-1 and MMP-9 (Ottino et al., 2002; Tao et al., 1995) and FN is a substrate of MMP-9 (Marom et al., 2007; Opdenakker et al., 2001). Expression of MMP-9 was increased in the anterior stroma of corneas treated with cPAF, which was decreased in presence of LAU-0901 and LXA4 (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5. Effect of PAF on FN and MMP-9.

A) Mouse corneal sections after 1 and 2 days of injury and treatments immunostained with anti-FN antibody (1:500 dilution). B) Immunostaining with anti-MMP-9 antibody (1:1000 dilution). DAPI was used to counter-stain the nuclei (red). C) Rabbit corneas in organ culture were incubated for 16 hours with cPAF (100nM) with or without LXA4 (100nM). Aliquots (20μl) of 2 ml media concentrated to 50 μl were analyzed by zymography as explained in Methods (2.9.). Gels were stained with Comassie blue. The position of the 92KDa MMP-9 is visible as a clear band in the gelatin gel. Similar results were obtained in a second experiment.

To further investigate the action of LXA4 on MMP-9, rabbit corneas in organ culture were used. This is a well-established method in our laboratory to study the action of PAF on MMP-9 expression and activity (Ottino and Bazan, 2001; Tao et al., 1995). As previously reported, corneas incubated with 100nM cPAF for 16 hours show an increased release of MMP-9 to the media (Fig. 5C). Presence of LXA4 diminished MMP-9 release. LXA4 alone does not have effect on MMP-9.

4. Discussion

Trauma to the cornea can have devastating consequences for vision. If the damage extends beyond the epithelial basement membrane and the corneal stroma is damaged, the risk of infection and sustained inflammation increases (Charakumnoetkanok et al., 2005). In corneal thickness lacerations, for example, it is important to ensure wound stability and in some cases sutures are necessary to close the wound. Corneal trauma produced after refractive surgery could produce complications induced by flap dislocation (LASIK) or rupture of corneal incisions following other surgical procedures. In all these cases it is important to promote re-epithelization and stroma healing.

Deep injuries to the cornea heal by activation of myofibroblasts that migrate to the injury site and contract the tissue (Fini, 1999; Fini and Stramer, 2005; Jester and Ho-Chang, 2003; Jester et al., 1996). As the main characteristic of the cornea is its transparency, excessive deposition of fibrotic repair tissue presents a challenge. On the other hand, a decrease in the repair response due to exacerbated inflammatory reaction could lead to ulceration and, in extreme cases, to tissue destruction.

In this study we recapitulate a deep injury by damaging the anterior stroma in an in vivo mouse model and add PAF to study the action of LXA4, a lipid involved in resolution of inflammation. The advantage of this model is that it allows us to observe the response to injury and PAF in the tissue microenvironment consisting of epithelial and stromal cells and the ECM components. We found that PAF significantly delays wound healing, corroborating our previous studies in vitro using rabbit corneas (Chandrasekher et al., 2002) where LXA4 inhibited the action of PAF. The significant increase in epithelial wound healing in corneas treated with LXA4 in the presence of PAF compared to vehicle could be attributed to the properties of LXA4 in resolution of inflammation and on its action as an intermediate in the epithelial proliferative signal of epidermal growth factor (Chiang et al., 2005; Kenchegowda et al., 2011)

Injury to the corneal surface elicits an inflammatory response that is marked by activation of stromal keratocytes and the recruitment of polymorphonuclear leukocytes. The PMNs infiltrate the corneal stroma through the limbal blood vessels and tear film. They function as phagocytes for pathogens and cellular debris. Although PMNs are needed for corneal wound healing (Gronert et al., 2005; Li et al., 2006) accumulation during an intense inflammatory reaction can delay recovery (Gan et al., 1999; Marrazo et al., 2011). Our study shows that PAF produced a marked cornea inflammation with significant increase in neutrophils infiltration, MPO activity and expression of IL-1α and KC. One possibility is that PAF activates the PAF-R expressed in neutrophils (Ishii et al. 2002; Prescott et al. 2000) and that their activation releases proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1α and KC that amplify the cellular response. In fact, our results demonstrate that LAU-0901 inhibits PMNs infiltration, MPO activity and expression of IL-1α and KC.

The main effect of LXA4 is to promote resolution of inflammation by inhibiting superoxide generation and PMN transmigration, and by stimulating uptake of cellular debris and apoptotic PMNs by macrophages (Serhan et al., 2008a, 2008b). The inhibition by LXA4 of PAF-induced excessive neutrophil infiltration, increased MPO activity and expression of IL-1α and KC is in agreement with the reported roles of LXA4 (Gronert, 2005; Gronert et al., 2005).

An interesting finding was that PAF decreased the number of α-SMA positive cells that migrate to the injury site and that LXA4 abolished that effect. After injury, keratocytes located in the wounded area enter in apoptosis while keratocytes outside the injury area became activated. The keratocytes changed phenotype to fibroblasts and myofibroblasts and began to migrate to the wound to repair the injury (Fini and Stramer, 2005). Recently, it has been reported that mouse bone marrow-derived cells can also generate myofibroblasts (Singh et al., 2012). During the cell transformation, genes are activated that encode ECM components such as FN and proteinases such as MMPs. Previous studies from our laboratory have shown that PAF increases the number of apoptotic keratocytes and stimulates the expression of MMPs (including MMP-9) in myofibroblasts (Chandrasekher et al., 2002; Ottino et al., 2005). The decrease in the number of α-SMA positive cells in the central cornea after PAF treatment was correlated with a decrease in FN and an increase in MMP-9 expression.

FN is a large adhesive protein able to interact with cells and other ECM components that has a key role in cellular migration. Therefore, a decrease in FN expression will decrease myofibroblast migration and consequently wound healing. In other tissues, FN degradation is dependent on the activation of MMPs (Ma et al., 2011). In fact, isolated mouse myofibroblasts show decreased FN expression in the presence of PAF that was blocked when the cells were treated with MMP inhibitors (data not shown). In addition, PMNs induced by PAF can increase MMP expression and contribute to FN degradation and decrease myofibroblasts migration. As mentioned, these cells express PAF-R and could be inhibited by LAU-0901 treatment.

This is the first report showing that the action of PAF in delaying wound healing is inhibited by LXA4. LXA4 acts through a seven transmembrane-G protein coupled receptor (FPR2/ALX) that is strongly expressed in the corneal epithelium (Gronert et al. 2005), endothelium (He et al., 2011), and in myofibroblasts (unpublished). As in the case of PAF in these in vivo experiments, activation of the receptor will happen not only in the corneal cells but in the inflammatory cells that arrive at the cornea after injury and PAF treatment (Chiang et al., 2006). The underlying mechanisms of LXA4 act to disrupt the inflammatory cascade induced by PAF through the inhibition of MMP-9 activation, increasing FN secretion, and increasing myofibroblast migration to promote wound healing in a deep injury.

In conclusion, PAF is a strong inflammatory mediator and a potent activator of MMP-9 that promotes FN degradation, thereby delaying epithelial wound healing and migration of myofibroblasts from the limbal area when the stroma is compromised. The inhibition of these events by LXA4 suggests that this lipid mediator could be important in the treatment of deep corneal injuries.

Highlights.

Platelet-activating factor is a lipid with strong inflammatory properties.

Lipoxin A4 is a lipid that mediates resolution of inflammation.

We investigate the interaction between these mediators in an in vivo mouse model.

Treatment with LXA4 reduced the injured area and PAF-induced MMP-9 expression.

LXA4 protects corneas with deep injures exacerbated by PAF.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Eye Institute grant EY004928

The authors thank Tiffany Russ for her help with animal handling, Darlene Guillot for figure assistance, and Phillip Karnell for editing.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bannenberg G, Serhan CN. Specialized pro-resolving lipid mediaotrs in the inflammatory response: An update. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1801:1260–1273. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazan HEP. Corneal injury alters eicosanoid formation in the rabbit anterior segment in vivo. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1987;28:314–3194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazan HEP. The synthesis and effects of eicosanoids in avascular ocular tissues. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1989;312:73–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazan HEP. Cellular and molecular events in corneal wound healing: Significance of lipid signaling. Exp Eye Res. 2005;4:453–63. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2004.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazan HE, Birkle DL, Beuerman RW, Bazan NG. Inflammation-induced stimulation of the synthesis of prostaglandins and lipoxygenase-reaction products in rabbit cornea. Curr Eye Res. 1985;14(3):175–9. doi: 10.3109/02713688509000847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazan HEP, Ottino P. The role of platelet-activating factor in the corneal response to injury. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2000;21:449–464. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(02)00011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazan HEP, Reddy STK, Lin N. Platelet-activating factor (PAF) accumulation correlates with injury in the cornea. Exp Eye Res. 1991;52:481–491. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(91)90046-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazan HEP, Tao Y, Bazan NG. Platelet-activating factor induces collagenase expression in corneal epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1993;90:8678–8682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley PP, Christensen RD, Rothstein G. Cellular and extracellular myeloperoxidase in pyrogenic inflammation. Blood. 1982a;60(3):618–622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley PP, Priebat DA, Christensen RD, Rothstein G. Measurement of cutaneous inflammation:estimation of neutrophil content with an enzyme marker. J Invest Dermatol. 1982b;78(3):206–209. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12506462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekher G, Ma X, Lallier TE, Bazan HEP. Delay of corneal epithelial wound healing and induction of keratocyte apoptosis by platelet activating factor. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:1422–1428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charakumnoetkanok P, Nouri P, Pineda R., II . The Cornea, Scientific Foundations & Chemical Practice. In: Foster CS, Azar DT, Dahlam CH, editors. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005. pp. 796–810. [Google Scholar]

- Chiang N, Arita M, Serhan CN. Anti-inflammatory circuitry:lipoxin, aspirin-triggered lipoxins and their receptor ALX. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2005;73(3-4):163–177. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang N, Serhan CN, Dahlen SE, Drazen JM, Hay DW, Rovati GE, Shimizu T, Yokomizo T, Brink C. The lipoxin receptor ALX: potent ligand-specific and stereoselective actions in vivo. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58(3):463–487. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fini ME. Keratocyte and fibroblast phenotypes in the repairing cornea. Prog Retin Eye Res. 1999;18(4):529–551. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(98)00033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fini ME, Stramer BM. How the corneal heals. Cornea-specific mechanism affecting surgical outcomes. Cornea. 2005;24(Suppl. 1):S2–S11. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000178743.06340.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan L, Fagerholm P, Kim HJ. Effect of leukocytes on corneal cellular proliferation and wound healing. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40(3):575–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gronert K. Lipoxins in the eye ad their role in wound healing. Prostaglandins Leukot Essential Fatty Acids. 2005;73:221–229. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gronert K, Masheswari N, Khan N, Hassan IR, Dunn M, Laniado Schwartzman M. A role for the mouse 12/15-lipoxygenase pathway in promoting epithelial wound healing and host defense. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(15):15267–15278. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410638200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J, Bazan NG, Bazan HEP. Alkali-induced corneal stromal melting prevention by novel platelet-activating factor (PAF) receptor antagonist. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124:70–78. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J, Kakazu A, Bazan NG, Bazan HEP. Aspirin-triggered lipoxin A4 (15-epi-LXA4) increases the endothelial viability of human corneas storage in Optisol-GS. J Ocular Pharmacol Therap. 2011;27(3):235–241. doi: 10.1089/jop.2010.0187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst JS, Balazy M, Bazan HEP, Bazan NG. The epithelium, endothelium, and stroma of the rabbit cornea generate 12-S-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid as the main lipoxygenase metabolite in response to injury. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:6726–6730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii S, Nagase T, Shimizu T. Platelet-activating factor receptor. Prostaglandins other Lipid Mediat. 2002;68-69:599–609. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(02)00058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizaki M, Shimoda M, Wakamatsu K, Ogro T, Yamanaka N, Kao CW, Kao WW. Stromal fibroblasts are associated with collagen IV in scar tissues of alkali-burned and lacerated corneas. Curr Eye Res. 1997;16(14):339–348. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.16.4.339.10684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jester JV, Barry-Lane PA, Cavanagh HD, Petroll WM. Induction of alpha-smooth muscle actin expression and myofibroblast transformation in cultured corneal keratocytes. Cornea. 1996;15(5):505–516. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jester JV, Ho-Chang J. Modulation of cultured corneal keratocyte phenotype by growth factors/cytokines control in vitro contractile and extracellular matrix contraction. Exp Eye Res. 2003;77(5):581–592. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(03)00188-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenchegowda S, Bazan HEP. Significance of lipid mediators in corneal injury repair. J Lipid Res. 2010;51:879–891. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R001347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenchegowda S, Bazan NG, Bazan HEP. EGF stimulates lipoxin A4 synthesis and modulates repair in corneal epithelial cells through ERK and p38 activation. Invest Opthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:2240–2249. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Burns AR, Smith CW. Two waves of neutrophil emigration in response to corneal epithelial abrasion: distinct adhesion molecule requirements. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47(5):1947–1955. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma S, Yang D, Li D, Tang B, Sun M, Yang Y. Cardiac extracellular matrix tenascin-C deposition during fibronectin degradation. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 2011;409:321–327. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X, Bazan HEP. Increased platelet-activating factor receptor gene expression by corneal epithelial wound healing. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:1696–1702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marom B, Rahat M, Lahat N, Weiss-Cerem L, Kinarty A, Bitterman H. Native and fragmented fibronectin oppositely modulate monocyte secretion of MMP-9. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81:1466–1476. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0506328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrazo G, Bellner L, Halilovic A, Volti GL, Drago F, Dunn MW, Laniado Schwartzman M. The role of neutrophils in corneal wound healing in HO-2 null mice. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):1–8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opdenakker G, Van den Steen PE, Van Damme J. Gelatinase B: a tuner and amplifier of immune functions. Trends Immunol. 2001;22(10):571–579. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)02023-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottino P, Bazan HE. Corneal stimulation of MMP-1, -9 and uPA by platelet-activating factor is mediated by cyclooxygenase-2 metabolites. Curr Eye Res. 2001;23(2):77–85. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.23.2.77.5471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottino P, He J, Axelrod TW, Bazan HEP. PAF-induced furin and MTI-MMP expression in independent of MMP-2 activation in corneal myofibroblasts. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:487–496. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottino P, Taheri F, Bazan HEP. Platelet-activating factor induces the gene expression of TIMP-1, TIMP-2, and PAI-1: Imbalance between the gene expression of MMP-9 and TIMP-1 and -2. Exp Eye Res. 2002;74(3):393–402. doi: 10.1006/exer.2001.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pflugfelder SC, Farley W, Luo L, Chen LZ, de Paiva CS, Olmos LC, Li DQ, Fini ME. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 knockout confers resistance to corneal epithelial barrier disruption in experimental dry eye. Am J Pathol. 2005;166(1):61–71. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62232-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan TM, Foster CS, Zagachin LM, Colvin RB. Role of fibronectin in the healing of superficial keratectomies in vitro. Invest Opthalmol Vis Sci. 1989;30(3):386–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prescott SM, Zimmerman GA, Stafforini DM, McIntyre TM. Platelet-activating factor and related lipid mediators. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:419–445. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayment EA, Upton Z. Finding the culprit: a review of the influences of proteases on the chronic wound environment. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2009;8(1):19–27. doi: 10.1177/1534734609331596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serhan CN, Chiang N, Van Dyke TE. Resolving inflammation:dual anti-inflammatory and pro-resolution lipid mediators. Nature Rev Immunol. 2008a;8:349–361. doi: 10.1038/nri2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serhan CN, Yacoubian S, Yang R. Anti-Inflammatory and proresolving lipid mediators. Annu Rev Pathol Mech Dis. 2008b;3:279–312. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathmechdis.3.121806.151409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh V, Agrawal V, Santhiago MR, Wilson SE. Stromal fibroblast-bone marrow derived cell interactions: Implications for myofibroblasts development in the cornea. Exp Eye Res. 2012;23(98C):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2012.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao Y, Bazan HEP, Bazan NG. Platelet-activating factor induces the expression of metalloproteinases-1 and -9, but not -2 or -3, in the corneal epithelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995;36(2):345–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yager DR, Nwomeh BC. The proteolitic environment of chronic wounds. Wound Repair Regen. 1999;7(6):433–441. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475x.1999.00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]