Abstract

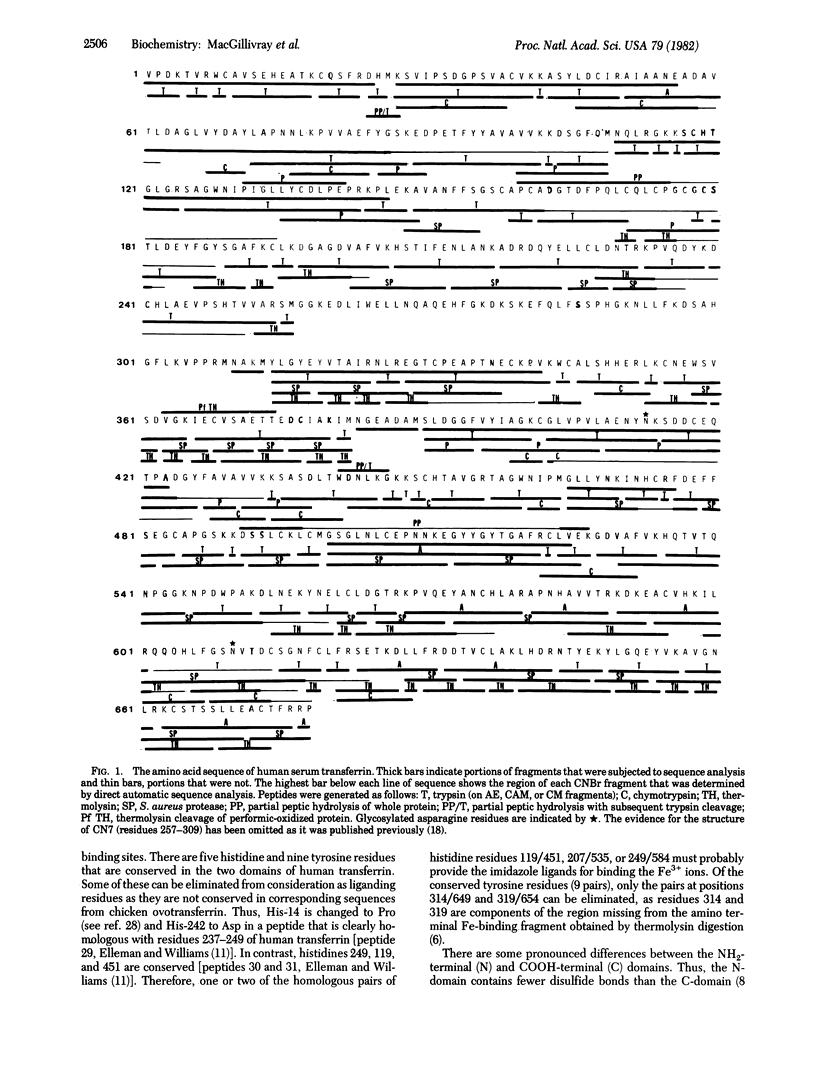

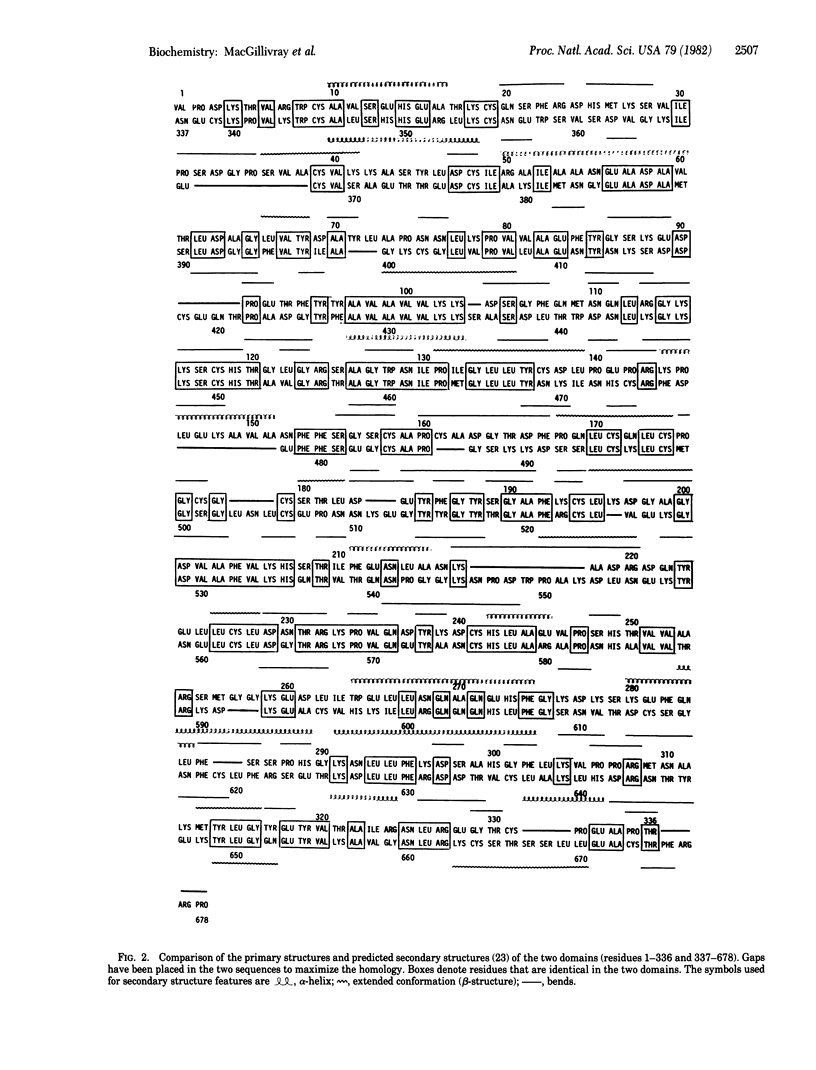

The complete amino acid sequence of human serum transferrin has been determined by aligning the structures of the 10 CNBr fragments. The order of these fragments in the polypeptide chain is deduced from the structures of peptides overlapping methionine residues and other evidence. Human transferrin contains 678 amino acid residues and--including the two asparagine-linked glycans--has an overall molecular weight of 79,550. The polypeptide chain contains two homologous domains consisting of residues 1-336 and 337-678, in which 40% of the residues are identical when aligned by inserting gaps at appropriate positions. Disulfide bond arrangements indicate that there are seven residues between the last half-cystine in the first domain and the first half-cystine in the second domain and therefore, a maximum of seven residues in the region of polypeptide between the two domains. Transferrin--which contains two Fe-binding sites--has clearly evolved by the contiguous duplication of the structural gene for an ancestral protein that had a single Fe-binding site and contained approximately 340 amino acid residues. The two domains show some interesting differences including the presence of both N-linked glycan moieties in the COOH-terminal domain at positions 413 and 610 and the presence of more disulfide bonds in the COOH-terminal domain (11 compared to 8). The locations of residues that may function in Fe-binding are discussed.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Aisen P., Listowsky I. Iron transport and storage proteins. Annu Rev Biochem. 1980;49:357–393. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.49.070180.002041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brock J. H., Arzabe F. R. Cleavage of differic bovine transferrin into two monoferric fragments. FEBS Lett. 1976 Oct 15;69(1):63–66. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(76)80654-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon H. B., Perham R. N. Reversible blocking of amino groups with citraconic anhydride. Biochem J. 1968 Sep;109(2):312–314. doi: 10.1042/bj1090312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorland L., Haverkamp J., Schut B. L., Vliegenthart J. F. The structure of the asialo-carbohydrate units of human serotransferrin as proven by 360 MHz proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. FEBS Lett. 1977 May 1;77(1):15–20. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(77)80183-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elleman T. C., Williams J. The amino acid sequences of cysteic acid-containing peptides from performic acid-oxidized ovotransferrin. Biochem J. 1970 Feb;116(3):515–532. doi: 10.1042/bj1160515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRAY W. R., HARTLEY B. S. THE STRUCTURE OF A CHYMOTRYPTIC PEPTIDE FROM PSEUDOMONAS CYTOCHROME C-551. Biochem J. 1963 Nov;89:379–380. doi: 10.1042/bj0890379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorinsky B., Horsburgh C., Lindley P. F., Moss D. S., Parkar M., Watson J. L. Evidence for the bilobal nature of diferric rabbit plasma transferrin. Nature. 1979 Sep 13;281(5727):157–158. doi: 10.1038/281157a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard P. N., Wang A. C., Sutton H. E. Transferrin DChi: the amino acid substitution. Biochem Genet. 1968 Nov;2(3):265–269. doi: 10.1007/BF01474766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huebers H., Josephson B., Huebers E., Csiba E., Finch C. Uptake and release of iron from human transferrin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981 Apr;78(4):2572–2576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.4.2572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunkapiller M. W., Hood L. E. Direct microsequence analysis of polypeptides using an improved sequenator, a nonprotein carrier (polybrene), and high pressure liquid chromatography. Biochemistry. 1978 May 30;17(11):2124–2133. doi: 10.1021/bi00604a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jollès J., Mazurier J., Boutigue M. H., Spik G., Montreuil J., Jollès P. The N-terminal sequence of human lactotransferrin: its close homology with the amino-terminal regions of other transferrins. FEBS Lett. 1976 Oct 15;69(1):27–31. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(76)80646-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karin M., Mintz B. Receptor-mediated endocytosis of transferrin in developmentally totipotent mouse teratocarcinoma stem cells. J Biol Chem. 1981 Apr 10;256(7):3245–3252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingston I. B., Williams J. The amino acid sequence of a carbohydrate-containing fragment of hen ovotransferrin. Biochem J. 1975 Jun;147(3):463–472. doi: 10.1042/bj1470463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lineback-Zins J., Brew K. Preparation and characterization of an NH2-terminal fragment of human serum transferrin containing a single iron-binding site. J Biol Chem. 1980 Jan 25;255(2):708–713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacGillivray R. T., Brew K. Transferrin: internal homology in the amino acid sequence. Science. 1975 Dec 26;190(4221):1306–1307. doi: 10.1126/science.1198114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez E., Lai C. Y. Regeneration of amino acids from thiazolinones formed in the Edman degradation. Anal Biochem. 1975 Sep;68(1):47–53. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(75)90677-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy B., Lehrer S. S. Circular dichroism of iron, copper, and zinc complexes of transferrin. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1972 Jan;148(1):27–36. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(72)90111-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha S. K., Brew K. A label selection procedure for determining the location of protein-protein interaction sites by cross-linking with bisimidoesters. Application to lactose synthase. J Biol Chem. 1981 May 10;256(9):4193–4204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton M. R., Brew K. Purification and characterization of the seven cyanogen bromide fragments of human serum transferrin. Biochem J. 1974 Apr;139(1):163–168. doi: 10.1042/bj1390163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton M. R., MacGillivray R. T., Brew K. The amino-acid sequences of three cystine-free cyanogen-bromide fragments of human serum transferrin. Eur J Biochem. 1975 Feb 3;51(1):43–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1975.tb03904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanaman T. C., Wakil S. J., Hill R. L. The complete amino acid sequence of the acyl carrier protein of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1968 Dec 25;243(24):6420–6431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang A. C., Sutton H. E., Howard P. N. Human transferrins C and D-Chi: an amino acid difference. Biochem Genet. 1967 Jun;1(1):55–59. doi: 10.1007/BF00487736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang A. C., Sutton H. E. Human Transferrins C and D1: Chemical Difference in a Peptide. Science. 1965 Jul 23;149(3682):435–437. doi: 10.1126/science.149.3682.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang A. C., Sutton H. E., Riggs A. A chemical difference between human transferrins B2 and C. Am J Hum Genet. 1966 Sep;18(5):454–458. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J. Iron-binding fragments from the carboxyl-terminal region of hen ovotransferrin. Biochem J. 1975 Jul;149(1):237–244. doi: 10.1042/bj1490237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J. The formation of iron-binding fragments of hen ovotransferrin by limited proteolysis. Biochem J. 1974 Sep;141(3):745–752. doi: 10.1042/bj1410745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]