Summary

Transgenic zebrafish embryos expressing tissue specific GFP can provide unlimited supply of primary embryonic cells. Agents promoting the differentiation of these cells may be beneficial for therapeutics. We report a high-throughput approach for screening small molecules that regulate cell differentiation using lineage-specific GFP transgenic zebrafish embryonic cells. After validating several known regulators of the differentiation of endothelial and other cell types, we performed a screen for pro-angiogenic molecules using undifferentiated primary cells from flk1-GFP transgenic zebrafish embryos. Cells were grown in 384-well plates with 12,128 individual small molecules and GFP expression was analyzed by an automated imaging system, allowing screening thousands of compounds weekly. As a result, 23 molecules were confirmed to enhance angiogenesis and 11 of them were validated to promote mammalian HUVEC proliferation and induce Flk1+ cells from mESCs. This strategy is generally applicable, as demonstrated by analyzing additional cell lineages using zebrafish expressing GFP in pancreatic, cardiac and dopaminergic cells.

Keywords: zebrafish, angiogenesis, primary embryonic cell, high-throughput screening

Introduction

In the past decade, the zebrafish has emerged as a viable model organism for bioactive small molecule discovery. Using zebrafish, it is now possible to assess the specificity, efficacy, and toxicity of small molecules in the context of live animals. The zebrafish and mammalian genetic and tissue/organ make-up are similar. Thus, small molecules discovered in zebrafish screens often have analogous effects in mammalian systems, and vice versa (Lally et al., 2007; Murphey et al., 2006; Patton and Zon, 2001; Peterson et al., 2000; Peterson et al., 2004; Stern and Zon, 2003; Zon and Peterson, 2005). For instance, a chemical screen targeting the Bmp pathway used a chemical library of 7,500 compounds to identify dorsomorphin, a molecule that has conserved inhibitory activity on Bmp type I receptors alk2, alk3, and alk7 and has dorsalizing effects on zebrafish embryos (Yu et al., 2008). Although impressive in terms of screening capacity as a vertebrate model, zebrafish embryonic assays still cannot match the scale and speed of cell culture assays. To overcome this limitation, we have developed automated analysis of cultured primary cell differentiation as a strategy to pre-select bioactive candidate compounds for further analysis (Fig. 1). This strategy uses genetically stable lineage-specific GFP transgenic zebrafish embryos of blastula/gastrula stages to generate pluripotent primary cells and allows them to differentiate in vitro. This culture system is equivalent to mammalian embryonic stem cells and can be used to screen tens of thousands of small molecule compounds or peptide agents for effects on GFP expressing/differentiating cell populations. Positive compounds from this primary screen can then be rescreened using mammalian assays and intact embryos.

Figure 1.

Overall strategy of primary cell-based high throughput screening for bioactive small molecules using cells dissociated from early transgenic zebrafish embryos.

Results

Reproducible fluorescent protein expression of transgenic lineages in primary cell culture

To visualize the differentiation of different cell lineages marked by fluorescent protein expression in primary culture, several transgenic lines expressing GFP or RFP in various cell types representing mesoderm, endoderm and ectoderm were used. These fish included stable transgenic lines expressing GFP or RFP under the regulatory sequences of flk1 (Kdrl) for vascular endothelial cells, gata1 and scl for hematopoietic cells, cmlc2 for cardiac myocytes, mlc for skeletal muscle, insulin for pancreatic endocrine beta cells and vmat2 for dopaminergic/vesicular monoamine transporter 2-positive neurons. Embryos from each of these transgenic lines were collected at late blastula/early gastrula stages and dissociated to generate primary cells. The dissociated embryonic cells, initially expressing no fluorescent proteins due to the undifferentiated status, were plated into multi-well plates and allowed to grow in L15 basic medium for 5–9 days. Most of the primary cells became attached to the bottom of the plate within 24 hours of culture. At the same time, a small but relatively stable percentage of cells in culture started to express transgenic fluorescent protein. Under our culture conditions, lineage-specific cells acquired characteristic features of cellular differentiation.

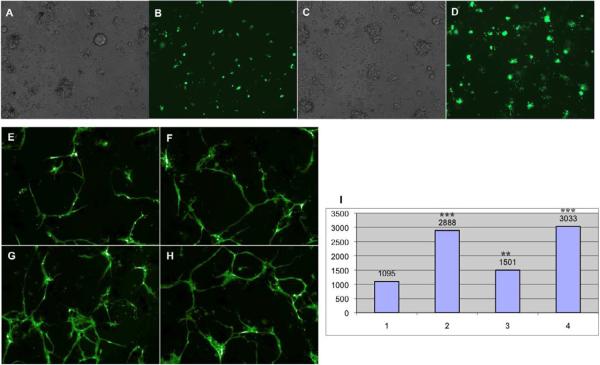

For vascular endothelial cell differentiation, flk1-GFP transgenic embryonic cells initially showed GFP expression after 24 hours of culture and individual cells appeared scattered. At day 2, flk1-GFP-expressing cells became elongated and clustered together to form network-like structures. At day 3 and day 4, flk1-GFP positive cells formed more extensive tube-like networks. These GFP-expressing cells underwent apoptosis and disappeared after 6 days of culture (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Differentiation of flk1-GFP labeled endothelial cells in primary culture. Flk1-GFP expressing endothelial cells are scattered at day 1 and become flatten and elongated at day 2–4, undergoing tube formation. After 5–6 days of culture, GFP positive cells start to die (in blue circles). A and B show DIC and Hoechst 33342 (5 μg/ml for 4.5–5 hours) staining on primary cells at day 6.

For hematopoietic cell differentiation, we used two fluorescent proteins to co-label different stages of differentiation. Gata1 is a marker for erythroid progenitors and differentiated primitive red blood cells, whereas Scl, a bHLH transcription factor, is expressed in both hematopoietic and vascular progenitor cells as well as in some neurons (Zhang and Rodaway, 2007). Double fluorescent transgenic embryos carrying transgenes for gata1-dsRed and scl-GFP were dissociated at the late blastula stage to allow visualization of hematopoietic cell differentiation in primary culture. We observed scl-GFP and gata1-dsRed expression from day 2 to day 9 of primary culture (Supplementary Fig. 1). Consistent with gene expression profiling in vivo, scl-GFP and gata1-dsRed were co-expressed in round-shaped hematopoietic progenitor cells (Supplementary Fig. 1, A–C, A for bright field, white arrowheads) and were also uniquely expressed in some non-round cells (Supplementary Fig. 1B, red arrowheads), which are presumably Scl-positive neuronal cells and Gata1-positive red blood cells (Supplementary Fig. 1C, blue arrowheads). Notably, gata1-dsRed-expressing round-shaped cells survived until day 9 and clustered into colony-like structures (Supplementary Fig. 1D and F, white circle and red cells), where some cells showed co-localized expression of gata1-dsRed and scl-GFP (Supplementary Fig. 1E and F, white arrowheads).

For myocardial differentiation marked by cmlc2-GFP expression, cultured primary cells began to express GFP at day 2 and continued until day 5. Some of the cells became contractile resembling cardiac cells (Supplementary Fig. 1G–J). The skeletal muscle-specific mlc-GFP maintained its expression from day 2 to day 4 and showed morphological resemblance to skeletal muscle cells (Supplementary Fig. 1K, L, N and bright field M for N). For pancreatic beta cell differentiation, marked by insulin-GFP expression, low frequency but clearly detectable GFP-positive cells became visible after 24 hours of culture (Supplementary Fig. 2A). Treatment of these primary cells with 1μM retinoic acid (RA) increased the number of insulin-GFP expressing cells by ~10-fold (Supplementary Fig. 2C) compared with the control (B) at day 2. This low frequency of GFP-positive cells in untreated primary cells provides a consistent baseline for detecting agents that can increase the differentiation of pancreatic beta cells, as demonstrated by the effects of RA treatment (Supplementary Fig. 2). For vmat2-GFP positive neurons, approximately 2% of cells were GFP-positive after 48 hours of culture (Supplementary Fig. 2D). Growth factor bFGF promoted the generation of vmat2-GFP labeled neurons and suppressed the differentiation of pigment cells (Supplementary Fig. 2E, G) compared with the untreated control (Supplementary Fig. 2D, F). There is a lack of zebrafish lines with faithful GFP expression specifically in dopaminergic neurons. Thus, our vmat2-GFP line can be useful for studying in vitro differentiation of dopaminergic neurons.

Response of endothelial GFP expression to regulatory agents in primary cell culture

The fibroblast growth factor (FGF) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) pathways are critical for vasculogenesis and angiogenesis in both development and pathological conditions (Cross and Claesson-Welsh, 2001; Poole et al., 2001). Recombinant FGF has been reported to induce VEGF expression and proliferation in human umbilical vascular endothelial cells (HUVECs) via both autocrine and paracrine mechanisms (Parsons-Wingerter et al., 2000; Seghezzi et al., 1998). To investigate whether exogenous growth factors can promote endothelial differentiation in zebrafish primary embryonic cell culture, we supplemented the culture medium with recombinant bFGF and VEGF. At 100 ng/ml, bFGF significantly stimulated flk1-GFP expression at day 1 of culture (Fig. 3A–D). Moreover, recombinant human VEGF121 significantly stimulated endothelial growth (Fig. 3. P=0.0007), consistent with previous reports that recombinant VEGF121 remarkably enhanced sprout formation and vessel length in HUVECs(Nakatsu et al., 2003). SB-431542 is a potent and specific inhibitor of transforming growth factor-β super-family type I activin receptor-like kinase (Alk) receptors Alk4, Alk5, Alk7, which are involved in many biological activities, including cell growth, differentiation, migration, survival and adhesion. Furthermore, the TGFβ/ALK5 pathway was found to inhibit endothelial cell migration and proliferation in vitro(Goumans et al., 2002). SB-431542 therefore acts to stimulate proliferation, differentiation, and vessel formation in endothelial cells derived from embryonic stem cells or from fetal mouse metatarsals (mouse metatarsal assays), when treated alone or in combination with VEGF (Liu et al., 2009; Watabe et al., 2003). Similarly, we observed that SB-431542 stimulated tube formation in flk1-GFP-labeled endothelial cells in primary culture at day 5 when cultured alone (Fig. 3G and I 2) or with VEGF (Fig. 3H and I 4). Compared with DMSO, SB-431542 increased total tube lengths 3 fold and number of branch points 2 fold. This finding suggests that SB-431542 can be used as a positive control for identifying other small molecules that can promote vascular differentiation in zebrafish primary cell culture. As a validation that the increased GFP expression represents the endogenous gene expression, we analyzed flk1 mRNA by qPCR and found that SB-431542 increased its level by 2.2 fold.

Figure 3.

Flk1-GFP labeled endothelial cells respond to growth factors and small molecules in primary culture. Endothelial cell proliferation and differentiation derived from Flk1-GFP are significantly promoted by 100 ng/ml bFGF (C, bright field; and D) compared with control (A, bright field; and B) at 22 hr after culture. Recombinant VEGF121 (20 ng/ml, F), small molecule SB-431542 (2μM, G) and the combination of both (H) also remarkably enhance Flk1-GFP endothelial tube formation compared with control (E) at day 5, which exhibit significant increase in total tube length (I: I1 - control, I2 - 2μM SB431542, I3 - 20 ng/ml VEGF121, I4 - 2μM SB431542 and 20 ng/ml VEGF121). The number values represent total tube length.

The above results suggest that cultured primary cells are capable of responding to positive stimuli under culture conditions. We next tested whether flk1-GFP expression in primary culture would respond to inhibitory molecules. SU5416, a potent inhibitor of VEGFR2 signaling, has been widely used to inhibit angiogenesis in vivo and in vitro(Fong et al., 1999; Serbedzija et al., 1999). Consistent with previous reports, SU5416 markedly inhibited the growth and migration of endothelial cells labeled with flk1-GFP in primary culture (Supplementary Fig. 3A–D). In addition, SU5416 suppressed bFGF-induced endothelial cell growth at 24 hr after culture (Supplementary Fig. 3E–L), indicating that the FGF signaling pathway promotes proliferation and differentiation of endothelial cells through the VEGF signaling pathway. Overall, these studies demonstrate that primary cell cultures from transgenic zebrafish embryos expressing cell lineage-specific GFP or RFP can be used to test either inductive or inhibitory agents, ranging from small molecules to proteins, for the discovery of potential therapeutic drugs.

High throughput screening for pro-angiogenic compounds using flk1-GFP primary culture

Tremendous effort has been made to identify angiogenesis inhibitors for their potential application in cancer therapeutics. However, much less attention has been directed to the identification of pro-angiogenesis drugs for treating diseases such as chronic wounds and peripheral arterial and ischemic heart diseases. In such conditions, the therapeutic goal is to stimulate angiogenesis to improve the delivery of survival factors to sites of tissue repair, mobilize regenerative stem cells, and ultimately, restore function to the tissues. With the ease of our flk1-GFP cultured cell assay, we performed a large-scale screen for pro-angiogenesis small molecules. Primary cells prepared from flk1-GFP transgenic embryos were seeded onto 384-well plates and treated with compounds. Images of flk1-GFP labeled endothelial cells were taken using an automatic fluorescence analyzer at day 5 of culture. A representative image of a 384-well plate is shown in Supplementary Fig. 4, with column 2 as a positive control and column 23 as a negative control. We observed a clear difference of tube-like endothelial cells between the two columns (Supplementary Fig. 4). We developed an algorithm that measures total tube length and branch points for identifying the positive compounds (methods and Table 1). The relative ratios of total tube length and branch points between experimental compounds and controls were used to determine if a compound was positive for promoting angiogenesis. For each plate, the average value of the column containing SB-431542 served as a positive control.

Table 1.

Ratios of selected positive hits to SB 431542 in total tube length and number of branch point

| Chemicals* | SB | A48 | ND | DTR | SST | A46 | A36 | A33 | A93 | A79 | LH | ZDM | A69 | A54 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ratio in total tube length | 1 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.8 |

| Ratio in branch point | 1 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.9 | 2 |

| Chemicals* | SB | A39 | A80 | A14 | GH | ADT | FH | MH5 | A62 | A86 | A65 | DIP | RL | PH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ratio in total tube length | 1 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 2 | 2 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 2.6 |

| Ratio in branch point | 1 | 2 | 2.1 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 2.1 | 1.8 | 2 | 1.5 | 2.3 | 2.5 | 3 | 2.8 | 2.4 |

SB, SB431542; A48, AST 5546348; ND, Nimodipine; DTR, DTR815; SST, Succinylsulfathiazole; A46, AST 6978646; A36, AST 6541036; A33, AST 6953386; A93, AST 5557493; A79, AST 6291379; LH, Levamisole hydrochloride; ZDM, Zimelidme dihydrochloride monohydrate; A69, AST 5062069; A54, AST 7153654; A39, AST 06978839; A80, AST 6014780; A14, AST 6156114; GH, Guanfacine hydrochloride; ADT, Androsterone; FH, Fenoterol hydrobromide; MH5, Methylhydantoin-5-(D); A62, AST 6417262; A86, AST 6978186; A65, AST 6953065; DP, Dipyridamole; RL, Rolipram; PH, Papaverine hydrochloride.

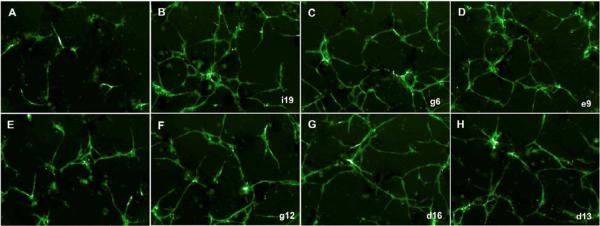

Four commercially available libraries (Biomol, Prestwick, Microsource and Tar) containing 12,128 compounds were selected for screening. Small molecules that induced total vascular tube lengths and number of branch points equal to or greater than SB-431542 were considered as positive hits, which yielded 165 candidate compounds. These candidates were re-screened and approximate 63% of them still passed the initial screening criteria. Candidates demonstrating 1.5 fold greater vascular tube lengths and numbers of branch points than SB 431542 treatment were selected for further analysis. This more stringent criterion yielded 26 compounds (Table 1). Fig. 4 shows representative images of enhanced endothelial proliferation and tube formation by candidate compounds at day 5 of culture.

Figure 4.

Representative images of candidate compounds that promoted endothelial proliferation and tube formation at day 5 (A, control; E, 2μM SB 431542; B–C and F–H, candidate compounds. i19, g6, e9, g12, d16, and d13, original plate well ID).

Validation of candidate compounds in mammalian cells and in vivo

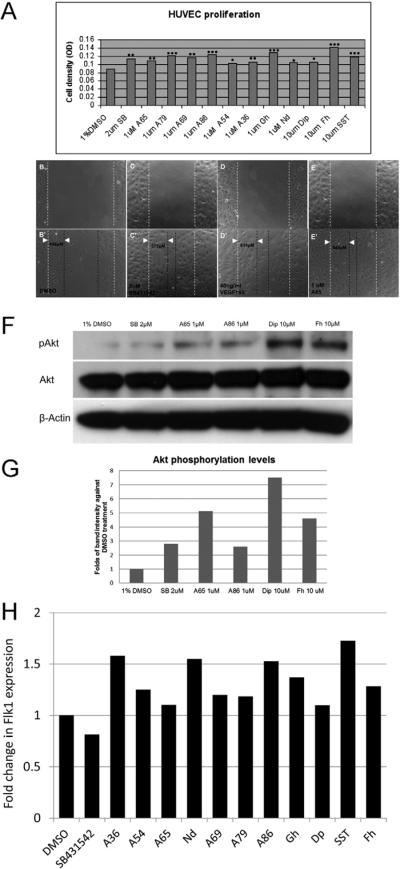

To determine whether candidate compounds also promote the growth of mammalian endothelial cells, we examined their activities in HUVEC assays. We tested 23 commercially available candidates by the MTT assay and found that 11 of them enhanced the proliferation of HUVECs by 19%–60% with a P-value of 0.02–0.000001 (Fig. 5A). Structures and names of these compounds are listed in Supplementary Fig 5. Additionally, these compounds enhanced the migration of HUVECs (Fig. 5B–E, only data of A65 is shown). Akt (protein kinase B) signaling plays a major role in regulating endothelial cellular proliferation, survival, migration, and adhesion, and its activation by phosphorylation stimulates proliferation through multiple cell cycle targets(Chen et al., 2008; Manning and Cantley, 2007). Hence, we selected six candidate compounds (A65, A86, Dip, Fh, Gh and SST) and investigated their ability to modulate phosphorylation levels of Akt. HUVECs were treated with these candidate compounds followed by Western blotting analysis using an anti-phospho-Akt antibody. For all six compounds, we observed increased phosphorylation of Akt compared with DMSO treated cells (Fig. 5 F and G, Supplementary Figure 6A), suggesting that pro-angiogenesis activities of these compounds involved Akt signaling pathways. As a confirmation, we co-treated the cells with wortmannin, a well-established inhibitor of PI3K/Akt pathway, and observed reversal of the proliferation effects of HUVEC by the selected compounds (Supplementary Figure 6B). Since Akt-dependent phosphorylation has been implicated in activating endothelial nitric oxide (NO) synthase (eNOS), which was found to be involved in cardiovascular homeostasis (Dimmeler et al., 1999), we tested if any of the compounds exerted their pro-angiogenesis activity through NO production. The same HUVEC proliferation assays were conducted with selected compounds adding the eNOS inhibitor L-NAME (Hood and Granger, 1998). This assay showed that pro-proliferative effect of SST, Dip, Gh and Fh on HUVEC could be reversed by eNOS inhibition (Supplementary Figure 6C), suggesting that Akt-eNOS pathway is involved in the mechanisms of action for these compounds.

Figure 5.

Test of candidate compounds in mammalian cells. A, Candidate compounds enhanced HUVEC proliferation significantly at 1μM or 10μM (P values = 0.0007, 0.005, 9.20E-05, 0.001, 1.40E-06, 0.021, 0.009, 2.70E-05, 0.02, 0.02,1.00E-6, and 2.0E-04, respectively for SB431542, A65, A79, A69, A86, A54, A36, Gh-Guanfacine hydrochloride, Nd-Nimodipine, Dip-Dipyridamole, Fh-Fenoterol hydrobromide, and STT-Succinylsulfathiazole) compared with 1% DMSO control. Data was analyzed from four independent experiments. B–E: Candidate compounds enhanced HUVEC migration. HUVEC migration was analyzed 24 hours after scratch wounds and drugs were added (B, C, D and E at 0 hour; B', C', D' and E' at 24 hours after treatment). Migration distances were measured in m and marked with white arrowheads. F. Akt phosphorylation levels increased in HUVECs by candidate compounds. Akt phosphorylation assay was performed using HUVECs treated with candidate small molecules for 8 hours (A65, A86, Dip and Fh) and positive compound (SB) compared with DMSO control. G. Western blot band intensity was analyzed using ImageJ program. After normalization against total Akt levels and β-actin levels, compounds enhanced Akt phosphorylation levels by 1.6-fold to 6.5-fold compared with DMSO control. H. Candidate compounds promoted Flk1 expression in differentiating mESCs. Cells were analyzed on day 4 of differentiation by flow cytometry for percentage of Flk1+. Expression levels were normalized to levels with DMSO.

To determine if these compounds could also induce mammalian endothelial differentiation, we examined the ability of the compounds to increase the number of Flk1+ cells generated from differentiating murine embryonic stem cells (mESCs). We tested the 11 compounds which were able to promote growth of HUVEC cells by adding the compound to mESCs on day 2 of differentiation and examining the level of Flk1 expression by flow cytometry on day 4 of differentiation (Fig 5H). Contrary to its role in the promotion of proliferation of endothelial cells, SB431542 inhibited the differentiation of mESCs into Flk1+ cells. This result was expected as inhibition of TGFβ signaling promotes self-renewal and inhibits differentiation in pluripotent cells (James et al., 2005). The 11 compounds discovered in this paper were all able to enhance the percentage of Flk1+ cells over that of control conditions. A36, Nd and SST were all very consistent in their ability to increase the percentage of Flk1+ cells by 50% (Fig 5H). Overall, these findings validate the effects of the small molecules identified from zebrafish embryo primary cell assays are largely conserved in mammalian endothelial cells.

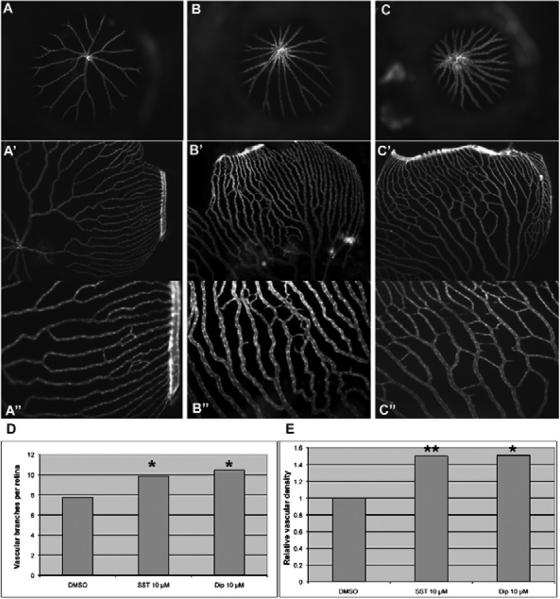

Intussusceptive angiogenesis, a mode of blood vessel formation and remodeling, occurs in lung and eye vasculature by internal division of the preexisting capillary plexus without sprouting (Djonov et al., 2000; Makanya et al., 2009). Next, we sought to investigate whether selected candidate compounds could enhance angiogenesis in adult zebrafish, as a test of pro-angiogenesis activity in vivo. To do so, we treated flk1-GFP transgenic adult fish with selected small molecules followed by observation of retinal vasculature after eye dissection (Cao et al., 2010). As shown in Fig 6, two selected drugs SST and Dip significantly enhanced retinal angiogenesis, as compared to the DMSO control treatment (N=22 retinas). SST and Dip increased the number of blood vessels by 27.2% (P=0.0216, N=12 retinas) and 34.3% (P=0.0220, N=13 retinas); and the vascular density by 49.8% (P=0.0090, N=12 retinas) and 50.9% (P=0.0250, N=13 retinas), respectively.

Figure 6.

Test of selected candidate compounds in vivo. A–C. Representative images of retinal vasculature treated with DMSO, SST and Dip. A, A', A": 0.5% DMSO; B, B', B": 10 μM SST. C, C', C": 10 μM Dip. A, B, and C.: Frontal view of retinal vasculature after removal of cornea and lens of Flk1-GFP transgenic adult eyes without flat mount. A' through C": Frontal view after flat mount. A", B" and C": higher magnification out of A', B' and C', respectively. D and E: Quantifications of vessel number and relative density per eye, respectively. P=0.0216 for SST and P =0.022 for Dip against control in vessel numbers. P=0.009 for SST and P=0.025 for Dip against control in relative density.

Discussion

Zebrafish has been established as an excellent vertebrate system for studying embryonic development, modeling human diseases, screening for pharmaceutical drugs and dissecting biological pathways. A key bottleneck in using zebrafish whole animals for drug screening is the limitation of throughput. Here, we have developed a primary cell-based approach that significantly expands the utility of this valuable model organism by taking advantage of the vast collection of transgenic zebrafish expressing GFP or RFP in specific tissues. Similar to the immortalized cell-based high throughput screening, our approach offers the advantage of high-throughput, high content (with multi-color transgenes) and high efficiency of screening small molecules. Given the fact that several pairs of fish can produce thousands of eggs, a sufficient supply of embryos to generate primary cells is never a limiting factor. A trained person can easily set up three 384-well plates per day. As shown above, since primary cells differentiate in a time frame similar to embryonic development, this method captures a biological process comparable to the zebrafish in vivo screening system, yet can be scaled up significantly. In addition, since it is difficult to visualize and quantify cells deeply embedded within the zebrafish embryo, such as pancreatic β cells, whole embryo compound screening is often inefficient. Primary cultured cells overcome this limitation by allowing direct visualization and statistical analysis of the cells of interest.

We have shown that 11 out of 26 chemicals were capable of enhancing the proliferation and migration of HUVECs, indicating that a reasonable number of small molecules identified in our zebrafish primary cell-based screen could be translated into the human endothelial system. In addition, these compounds were able to promote the endothelial differentiation from mESCs. For those compounds that failed to promote mammalian endothelial cell proliferation and differentiation, it is likely that their target proteins have some different properties between zebrafish and mammalian species. Further validating our findings for those positive hits in both zebrafish and mammalian cells is that several of these compounds have been previously implicated in promoting vascular formation. Nimodipine, a calcium channel antagonist and a dilator of blood vessels, has been reported to promote vascularization in suspension cell grafts of rats, although the drug has no lasting effects on vascularization in the intact brain (Finger and Dunnett, 1989). It was proposed that nimodipine might increase endothelial survival, reduce loss of existing blood vessels, and stimulate existing vessels in the nearby area to grow into the graft. Dipyridamole, a compound that inhibits thrombus formation when given chronically and causes vasodilation when given at high doses over a short time, was reported to induce capillary growth in normal and hypertrophic hearts of rabbits (Torry et al., 1992). It was also observed to enhance ischemic angiogenesis in the diabetic hind limb by preferentially promoting endothelial proliferation in mice (Pattillo et al., 2011). It is believed that elevated oxidative stress and reduced NO bioavailability are hallmarks of endothelial cell dysfunction and cardiovascular pathology during diabetes in both humans and animals. Therefore, dipyridamole was further characterized to enhance ischaemia-induced angiogenesis and arteriogenesis through increasing nitrite/NO production and decreasing oxidative stress (Pattillo et al., 2011; Venkatesh et al., 2010). Guanfacine, a α2-adrenoceptor agonist and vasodilator, was shown to prevent the cardiovascular effects of hemispheric ischaemia by inducing a surge of luminal NO in rats (Figueroa et al., 2001; Saad et al., 1986). Fenoterol hydrobromide, a β2-adrenoceptor agonist, was also found to induce NO production and eNOS phosphorylation in endothelial cells (Figueroa et al., 2009); but whether it could stimulate angiogenesis was not reported. Nonetheless, these collective earlier reports are consistent with our finding that the pro-proliferative effect of SST, Dip, Gh and Fh on HUVEC was reversible by eNOS inhibition. FenoterSuccinylsulfathiazole, an antibacterial drug, has never been previously reported to enhance endothelial cell growth. It will be interesting to determine if this drug can be used in treating vascular deficiency diseases. It is worth mentioning that 5 of these 11 compounds are FDA approved drugs that can be directly used in humans. For the rest of the compounds, further studies of efficacy, pharmacokinetics and safety are needed to determine their application to angiogenesis deficiency diseases.

Experimental Procedure

Preparation of zebrafish embryo primary cells

Transgenic zebrafish lines or promoters used for making the lines are: gata1-dsRed (Long et al., 1997), scl-GFP (an enhancer trap line identified in house) (Wen et al., 2008), cmlc2-GFP, mlc-GFP, flk1-GFP, insulin-GFP(Huang et al., 2001) and vmat2-GFP (Wen et al., 2008).

On day one, ~30 pairs of transgenic fish were set up with dividers in the afternoon and released together to mate next early morning. Collected eggs were incubated at 32°C in fish water containing 1× antibiotics (Antibiotic-Antimycotic Solution, Cellgro). Later at gastrulation stage, embryos were cleaned several times with Holtfreter's solution that was pre-warmed at 32°C.

Embryos were allowed to continuously grow to 80% epiboly/tailbud stage or stage of interest at 32°C. In the meantime, 20 ul of Leibovitz L15 medium (phenol-red free, 5% FBS, 1% antibiotics) was added to each of 384 wells of the Greiner μClear Black Plate (T-3037-9, ISC Bioexpress, by Greiner Bio-one) using a multi-channel pipette in a sterile tissue culture hood. To each well, compound (normally 10uM) was then individually added using an automated liquid handler. The entire columns of 2 and 23 for a 384-well plate were reserved as positive (2 uM SB-431542) and negative (1% DMSO) controls, respectively.

Cleaned embryos were combined and treated in 8ml Holtfreter's solution containing 3ug/ml pronase for ~8 minutes. This allowed removal of chorions after several washes with Holtfreter's solution. Dechorinated healthy embryos were transferred to a clean tissue culture dish. To produce enough cells for one 384-well plate, ~1600 embryos should be prepared.

The embryos were then bleached in 0.04% Sodium Hypochloride (Aldrich, Cat. 23930-5) for exactly 3 minutes followed by 5 × washes in PBS. Embryos were then transferred to a 1.5ml Eppendorf tube, excess PBS removed and homogenized using blue pestles (Fisher Scientific). After homogenization, cell aggregates were transferred to a tube containing 6ml of 0.05% trypsin (Invitrogen) and incubated at 37°C for 10 minutes. Then, equal volume (6ml) of medium containing 10% FBS was added to the tube to stop trypsin digestion. The cell suspension was gently mixed and then centrifuged at 800 rpm for 4–6 minutes at 4°C (Beckman Allegra 25R Centrifuge). The cell pellets were re-suspended in the culture medium (18 ml for each 1600 embryos) and 40 μl cell suspension was distributed into each of 384 wells using a multi-channel pipette. Cells were grown at 32°C without CO2. At day 5, fluorescence of cultured tg(kdrl:gfp) cells was imaged using the ImageXpress Micro Screening System (Molecular Devices) equipped with LHS-H100P-1 camera (Nikon, Japan). Image of each well was analyzed with Angiogenesis Tube Formation (RD-1) of High Content Image Processing Software to generate data of tube length and branch points (MetaXpress, Molecular Devices).

Endothelial proliferation and migration assays

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) were purchased from Invitrogen (C-015-5C) and cultured in the endothelial cell growth medium (MV2 plus complete supplement, Promocell, C-22221 and C-39221) at 37°C and 5% CO2. For proliferation assay, HUVECs were seeded at a density of 6 × 103 cells / well in 96-well plate in normal growth medium for 24 hrs. Media was then changed to 0.5% (v/v) FBS containing MV2 for serum starvation for 24 hours. Cells were stimulated with hVEGF165 (Cell Signaling, #8065) and small molecules for 72 hours(Holmes et al., 2010), and the number of viable cells was determined using MTT assay (Twentyman and Luscombe, 1987). For MTT assay, 2ml fresh MTT (Thiazolyl Blue Tetrazolium Bromide, Sigma M2128) solution was prepared per 96-well plate at 5mg/ml in PBS and 20 μl MTT solution was added to each well. Plates were put on a shaker at 150rpm for 5 minutes to thoroughly mix the MTT into the media. Plates were incubated (37°C, 5% CO2) for 1–5 hours to allow the MTT to be metabolized. The media were discarded and formazan (MTT metabolic product) was dissolved in 200 μl DMSO. Plates were put on a shaker at 150rpm for 5 minutes to thoroughly mix the formazan into the solvent. Optical density was recorded at 570nm and subtracted with background at 630nm. Optical density is directly correlated with cell quantity. For migration assay, HUVECs were seeded at a density of 5×104 cells/well in 24-well plate in normal growth medium for 48 hrs. Media were then changed to 1% (v/v) FBS containing MV2 for serum starvation for 24 hours. A scratch was introduced to the cell monolayer using a sterile 200 μl pipette tip followed by incubation with hVEGF165 (Cell Signaling, #8065) and small molecules for 16–24 hours(Holmes et al., 2010). The migration distance was measured in μM for comparison.

Akt phosphorylation assays by Western blotting analysis

5×105 HUVEC cells/well were seeded in 6-well plate and cultured in the medium MV2 plus supplement for 24 hrs followed by 12 hrs starvation in the medium MV2 plus 0.5% FBS. After starvation, cells were treated with DMSO or compounds in the same medium for eight hours followed by total protein preparation. Phospho-Akt (S473) antibody and total Akt (C67E7) antibody were purchased from Cell Signaling (p-Akt #9271 and Akt (pan) #4691) and protein gels were purchased from Thermo Scientific (Cat. 25200–25244). The Akt kinase assay was performed using protocols provided by the manufactories.

Growth and differentiation of mESCs

iER71 mESCs were maintained in the undifferentiated state on a mitomycin C inactivated CF1 MEF feeder layer. Cells were grown in KO- DMEM (Invitrogen), 15% FBS (Hyclone), 1× NEAA, 1× Penicillin/Streptomycin/L-glutamine, 55 μM β-mercaptoethanol (all Invitrogen) and 1000U/ ml LIF (Millipore). Differentiation was induced by plating 1× 10^5 cells/ well of a 6 well plate in IMDM (Invitrogen), 15% FBS (Hyclone), 1× Penicillin/Streptomycin/L-glutamine, 55 μM β-mercaptoethanol (both Invitrogen) and 50 μM Ascorbic Acid. Compounds were added on day 2 of differentiation.

Flow cytometry

Cells were harvested by 0.25% Trypsin digestion on day 4 of differentiation. Immunolabeling was performed with 1:100 PE conjugated anti-mouse Flk1 (KDR) (BD-Pharmingen) in PBS with 1% BSA and analyzed on a BD LSRFortessa cell analyzer.

Retinal angiogenesis assay

Individual flk1-GFP transgenic adult fish (14-month) was incubated in 60 ml fish water containing 0.5% DMSO and selective compounds or only 0.5% DMSO for 72 hrs followed by eye dissection under a Zeiss dissection microscope (Cao et al., 2010). Imaging was obtained and analyzed on Axioplan 2 Zeiss microscope with fluorescence. Blood vessel branches within a circle with radius of 90 μm from the optic disc were counted using OpenLab software. Total vascular density was measured as percentage of area covered by fluorescent vessel within the same circle centering at the optic disc per eye.

Supplementary Material

Highlights

Zebrafish lineage-specific transgene reporter expressions respond to exogenous chemical stimuli in primary embryonic cell culture

High throughput screening is performed for identifying pro-angiogenic chemicals using primary cells

Pro-angiogenic compounds identified from zebrafish primary cell screen can be validated in vivo and in mammalian cells

Acknowledgments

We thank Zahra Tehrani and Matthew Veldman for critical proofreading of the manuscript; Anqi Liu and Yuan Dong for zebrafish husbandry, and Robert Damoiseaux for preparation of chemical libraries. This work was in part supported by research grant from the National Institutes of Health to S.L. (DK54508).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Cao Z, Jensen LD, Rouhi P, Hosaka K, Lanne T, Steffensen JF, Wahlberg E, Cao Y. Hypoxia-induced retinopathy model in adult zebrafish. Nat Protoc. 2010;5:1903–1910. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Liu F, Ren Q, Zhao Q, Ren H, Lu S, Zhang L, Han Z. Hemangiopoietin promotes endothelial cell proliferation through PI-3K/Akt pathway. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2008;22:307–314. doi: 10.1159/000149809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross MJ, Claesson-Welsh L. FGF and VEGF function in angiogenesis: signalling pathways, biological responses and therapeutic inhibition. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2001;22:201–207. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01676-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimmeler S, Fleming I, Fisslthaler B, Hermann C, Busse R, Zeiher AM. Activation of nitric oxide synthase in endothelial cells by Akt-dependent phosphorylation. Nature. 1999;399:601–605. doi: 10.1038/21224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djonov V, Schmid M, Tschanz SA, Burri PH. Intussusceptive angiogenesis: its role in embryonic vascular network formation. Circ Res. 2000;86:286–292. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.3.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa XF, Poblete I, Fernández R, Pedemonte C, Cortés V, Huidobro-Toro JP. NO production and eNOS phosphorylation induced by epinephrine through the activation of beta-adrenoceptors. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297:H134–143. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00023.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa XF, Poblete MI, Boric MP, Mendizábal VE, Adler-Graschinsky E, Huidobro-Toro JP. Clonidine-induced nitric oxide-dependent vasorelaxation mediated by endothelial alpha(2)-adrenoceptor activation. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;134:957–968. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finger S, Dunnett SB. Nimodipine enhances growth and vascularization of neural grafts. Exp Neurol. 1989;104:1–9. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(89)90001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong TA, Shawver LK, Sun L, Tang C, App H, Powell TJ, Kim YH, Schreck R, Wang X, Risau W, et al. SU5416 is a potent and selective inhibitor of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (Flk-1/KDR) that inhibits tyrosine kinase catalysis, tumor vascularization, and growth of multiple tumor types. Cancer Res. 1999;59:99–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goumans MJ, Valdimarsdottir G, Itoh S, Rosendahl A, Sideras P, ten Dijke P. Balancing the activation state of the endothelium via two distinct TGF-beta type I receptors. EMBO J. 2002;21:1743–1753. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.7.1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes K, Chapman E, See V, Cross MJ. VEGF stimulates RCAN1.4 expression in endothelial cells via a pathway requiring Ca2+/calcineurin and protein kinase C-delta. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11435. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood J, Granger HJ. Protein kinase G mediates vascular endothelial growth factor-induced Raf-1 activation and proliferation in human endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:23504–23508. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.36.23504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, Vogel SS, Liu N, Melton DA, Lin S. Analysis of pancreatic development in living transgenic zebrafish embryos. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2001;177:117–124. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(01)00408-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James D, Levine AJ, Besser D, Hemmati-Brivanlou A. TGFbeta/activin/nodal signaling is necessary for the maintenance of pluripotency in human embryonic stem cells. Development. 2005;132:1273–1282. doi: 10.1242/dev.01706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lally BE, Geiger GA, Kridel S, Arcury-Quandt AE, Robbins ME, Kock ND, Wheeler K, Peddi P, Georgakilas A, Kao GD, et al. Identification and biological evaluation of a novel and potent small molecule radiation sensitizer via an unbiased screen of a chemical library. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8791–8799. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Kobayashi K, van Dinther M, van Heiningen SH, Valdimarsdottir G, van Laar T, Scharpfenecker M, Löwik CW, Goumans MJ, Ten Dijke P. VEGF and inhibitors of TGFbeta type-I receptor kinase synergistically promote blood-vessel formation by inducing alpha5-integrin expression. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:3294–3302. doi: 10.1242/jcs.048942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long Q, Meng A, Wang H, Jessen JR, Farrell MJ, Lin S. GATA-1 expression pattern can be recapitulated in living transgenic zebrafish using GFP reporter gene. Development. 1997;124:4105–4111. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.20.4105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makanya AN, Hlushchuk R, Djonov VG. Intussusceptive angiogenesis and its role in vascular morphogenesis, patterning, and remodeling. Angiogenesis. 2009;12:113–123. doi: 10.1007/s10456-009-9129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning BD, Cantley LC. AKT/PKB signaling: navigating downstream. Cell. 2007;129:1261–1274. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphey RD, Stern HM, Straub CT, Zon LI. A chemical genetic screen for cell cycle inhibitors in zebrafish embryos. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2006;68:213–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2006.00439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatsu MN, Sainson RC, Pérez-del-Pulgar S, Aoto JN, Aitkenhead M, Taylor KL, Carpenter PM, Hughes CC. VEGF(121) and VEGF(165) regulate blood vessel diameter through vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 in an in vitro angiogenesis model. Lab Invest. 2003;83:1873–1885. doi: 10.1097/01.lab.0000107160.81875.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons-Wingerter P, Elliott KE, Clark JI, Farr AG. Fibroblast growth factor-2 selectively stimulates angiogenesis of small vessels in arterial tree. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:1250–1256. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.5.1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattillo CB, Bir SC, Branch BG, Greber E, Shen X, Pardue S, Patel RP, Kevil CG. Dipyridamole reverses peripheral ischemia and induces angiogenesis in the Db/Db diabetic mouse hind-limb model by decreasing oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;50:262–269. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.10.714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton EE, Zon LI. The art and design of genetic screens: zebrafish. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:956–966. doi: 10.1038/35103567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson RT, Link BA, Dowling JE, Schreiber SL. Small molecule developmental screens reveal the logic and timing of vertebrate development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:12965–12969. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.24.12965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson RT, Shaw SY, Peterson TA, Milan DJ, Zhong TP, Schreiber SL, MacRae CA, Fishman MC. Chemical suppression of a genetic mutation in a zebrafish model of aortic coarctation. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:595–599. doi: 10.1038/nbt963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole TJ, Finkelstein EB, Cox CM. The role of FGF and VEGF in angioblast induction and migration during vascular development. Dev Dyn. 2001;220:1–17. doi: 10.1002/1097-0177(2000)9999:9999<::AID-DVDY1087>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saad MA, Elghozi JL, Meyer P. Baroreflex sensitivity alteration following transient hemispheric ischaemia in rats: protective effect of alphamethyldopa and guanfacine. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1986;13:525–534. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1986.tb00935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seghezzi G, Patel S, Ren CJ, Gualandris A, Pintucci G, Robbins ES, Shapiro RL, Galloway AC, Rifkin DB, Mignatti P. Fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2) induces vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression in the endothelial cells of forming capillaries: an autocrine mechanism contributing to angiogenesis. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:1659–1673. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.7.1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serbedzija GN, Flynn E, Willett CE. Zebrafish angiogenesis: a new model for drug screening. Angiogenesis. 1999;3:353–359. doi: 10.1023/a:1026598300052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern HM, Zon LI. Cancer genetics and drug discovery in the zebrafish. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:533–539. doi: 10.1038/nrc1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torry RJ, O'Brien DM, Connell PM, Tomanek RJ. Dipyridamole-induced capillary growth in normal and hypertrophic hearts. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:H980–986. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.262.4.H980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twentyman PR, Luscombe M. A study of some variables in a tetrazolium dye (MTT) based assay for cell growth and chemosensitivity. Br J Cancer. 1987;56:279–285. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1987.190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh PK, Pattillo CB, Branch B, Hood J, Thoma S, Illum S, Pardue S, Teng X, Patel RP, Kevil CG. Dipyridamole enhances ischaemia-induced arteriogenesis through an endocrine nitrite/nitric oxide-dependent pathway. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;85:661–670. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watabe T, Nishihara A, Mishima K, Yamashita J, Shimizu K, Miyazawa K, Nishikawa S, Miyazono K. TGF-beta receptor kinase inhibitor enhances growth and integrity of embryonic stem cell-derived endothelial cells. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:1303–1311. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200305147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen L, Wei W, Gu W, Huang P, Ren X, Zhang Z, Zhu Z, Lin S, Zhang B. Visualization of monoaminergic neurons and neurotoxicity of MPTP in live transgenic zebrafish. Dev Biol. 2008;314:84–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu PB, Hong CC, Sachidanandan C, Babitt JL, Deng DY, Hoyng SA, Lin HY, Bloch KD, Peterson RT. Dorsomorphin inhibits BMP signals required for embryogenesis and iron metabolism. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:33–41. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang XY, Rodaway AR. SCL-GFP transgenic zebrafish: in vivo imaging of blood and endothelial development and identification of the initial site of definitive hematopoiesis. Dev Biol. 2007;307:179–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zon LI, Peterson RT. In vivo drug discovery in the zebrafish. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4:35–44. doi: 10.1038/nrd1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.