Abstract

Nomograms to predict normal aortic root diameter for body surface area (BSA) in broad ranges of age have been widely used, but are limited by lack of consideration of gender effects, jumps in upper limits of aortic diameter between age strata, and data from older teenagers. Sinuses of Valsalva diameter was measured by American Society of Echocardiography convention in normal-weight, non-hypertensive, non-diabetic individuals ≥15 years old without aortic valve disease from clinical or population-based samples. Analyses of covariance and linear regression with assessment of residuals identified determinants and developed predictive models for normal aortic root diameter. Among 1,207 apparently normal individuals ≥15 years old (54% female), aortic root diameter was 2.1 to 4.3 cm. Aortic root diameter was strongly related to BSA and height (both r=0.48), age (r=0.36) and male gender (+2.7 mm adjusted for BSA and age) (all p<0.001). Multivariable equations using age, gender, and either BSA or height predicted aortic diameter strongly (both R=0.674, p <0.001) with minimal relation of residuals to age or body size:

for BSA: 2.423+(age [yrs]*0.009) + (bsa [m2]*0.461) -(sex [1=M, 2=F]*.267) SEE = 0.261 cm

for height: 1.519+(age [yrs]*0.010) + (ht [cm]*.010)-(sex [1=M, 2=F]*.247) SEE = 0.215 cm.

In conclusion, aortic root diameter is larger in men and increases with body size and age. Regression models incorporating body size, age and gender are applicable to adolescents and adults without limitations of previous nomograms.

Keywords: Aortic root, echocardiography, normal limits

Introduction

Aortic dilatation is strongly associated with the presence and severity of aortic regurgitation (1–2) and risk for aortic dissection (3). Nomograms to predict normal aortic root diameter for body surface area (BSA) in broad ranges of age (4) have been widely used to detect aortic enlargement in clinical practice and adopted in guidelines (5–6). However, these nomograms were based on a modest-sized reference population that did not permit definitive consideration of gender effects, and are limited by jumps in upper limits of normal aortic diameter at transitions to older age strata, and insufficient data on normal limits for older teenagers. In addition, it is uncertain whether use of BSA as the measure of body size under-recognizes aortic dilatation in obese individuals. Accordingly, the present study assessed the relations of aortic root diameter determined by echocardiography to age, gender and to height or body surface area as alternative measures of body size in a large population of apparently normal individuals ≥15 years old.

Methods

The present reference population included individuals who were non-obese, normotensive, non-diabetic and free of clinically overt cardiovascular disease or aortic valve disease recognized by echocardiography from the following sources: 1) 143 subjects ≥15 years old from the New York population reported by Roman et al (4); 2) 510 adolescents or adults who participated in the 1st examination of the Strong Heart Family Study cohort (7–8); 3) 459 individuals ≥15 years old who underwent echocardiography in the 2nd Family Blood Pressure Program examination (9–10); and 122 individuals ≥17 years old who had echocardiograms at the 1st or 2nd HyperGEN examination (11). Height and weight were measured by standardized methods at the clinic exams; body surface area (BSA) was calculated by the Dubois and Dubois method (12):

BSA (m2) = 0.007184 × H0.725 × W0.425 with H height in cm, W weight in kg This method has been shown to yield BSA values similar to those from the Haycock and other formulae in individuals with BSA >0.7 m2, encompassing the range of body sizes in the present study population (13). Because BSA is a second-power measure while aortic diameter is a first-power measure, BSA0.5 was considered in alternative analyses.

Echocardiograms were performed by standardized methods and centrally read at Cornell Medical Center. Parasternal long and short-axis views were used to record on videotape ≥10 consecutive beats of 2-dimensional and M-mode recordings of the aortic root and left atrium and of left ventricular (LV) internal diameter and wall thicknesses at or just below the tip of the anterior mitral leaflet; color Doppler was used to search for mitral and aortic regurgitation. The apical window was used to record ≥10 cycles of 2-, 3-, 4-, and 5-chamber images and color Doppler recordings to assess LV wall motion and identify mitral and aortic regurgitation. Individuals with bicuspid aortic valves or with more than mild aortic or mitral regurgitation or any degree of aortic stenosis were excluded from the present analyses.

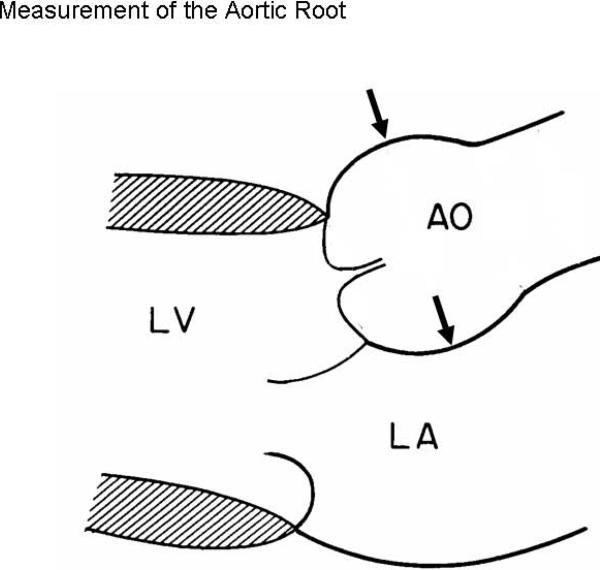

Echocardiograms were preliminarily read by a first reader and over-read by highly experienced readers (RBD in >90%) blinded to subjects' clinical data. Aortic root diameter was measured as previously described (4, 6) at end-diastole by the leading-edge convention in the parasternal or occasionally apical long-axis view that showed the maximum diameter parallel to the aortic annular plane (Figure 1). Aortic annular diameter was measured between the hinging points of the right and non-coronary cusps of the aortic valve in systole.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the aortic root showing measurement of aortic annular diameter and aortic root diameter at maximum width parallel to the aortic annular plane, by American Society of Echocardiography leading edge convention (4, 6) (By permission of the American Journal of Cardiology).

Data are reported as mean±SD for continuous variables or proportions for categorical variables. Univariate relations of continuous variables of age and measures of body size with sinuses of Valsalva diameter were assessed by least-squares linear correlation. Differences between genders were assessed by t tests for independent samples, in the entire population and in subgroups 15–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64 and ≥65 years old. Age, gender and body size measures were significantly related to aortic root diameter in univariate analyses; they were then entered in multiple linear regression models considering age, gender and either BSA or height as independent variables and sinuses of Valsalva diameter as the dependent variable. Residuals of observed aortic diameter versus that predicted by multivariate models were calculated and their relations to age, primary measures of body size (BSA or height) and body mass index were assessed. Two-tailed P <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

New York subjects included 70 women and 73 men 41±16 years old (range 15–74), with mean BSA 1.83±0.21 m2 (range 1.29–2.40), height 1.67±0.14 m (1.52–1.91), weight 68±16 kg (49–110 kg) and aortic root diameter 3.13±0.42 cm (2.1 – 4.3). Strong Heart Study participants included 288 female and 222 male American Indians 41±16 years old (range 15–86), with mean BSA 1.71±0.15 m2 (1.27–2.32), height 1.68±0.09 m (range 1.47–2.06), weight 62±9 kg (38–97 kg) and aortic root diameter 3.12±0.31 cm (2.4 – 4.3). Family Blood Pressure Program participants included 240 women and 219 men 41±14 years old (range 15–78), with mean BSA 1.71±0.20 m2 (1.25–2.41), height 1.67±0.11 m (range 1.43–1.98), weight 63±11 kg (35–108 kg) and aortic root diameter 3.18±0.39 cm (2.2 – 4.3); 166 were of African-American, 120 of Hispanic and 173 of Japanese-American ethnicity. HyperGEN participants included 70 women and 52 men 33±9 years old (range 17–50), with mean BSA 1.75±0.19 m2 (1.13–2.25), height 1.70±0.10 m (1.49–1.92), weight 65±11 kg (41–99 kg) and aortic root diameter 3.08±0.31 cm (2.4 – 3.9); 60 were of African-American and 62 of Caucasian ethnicity.

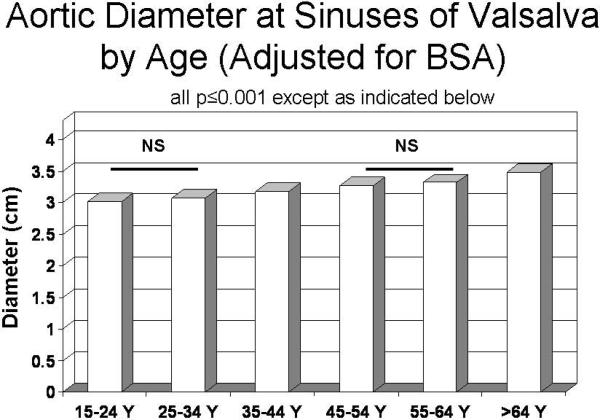

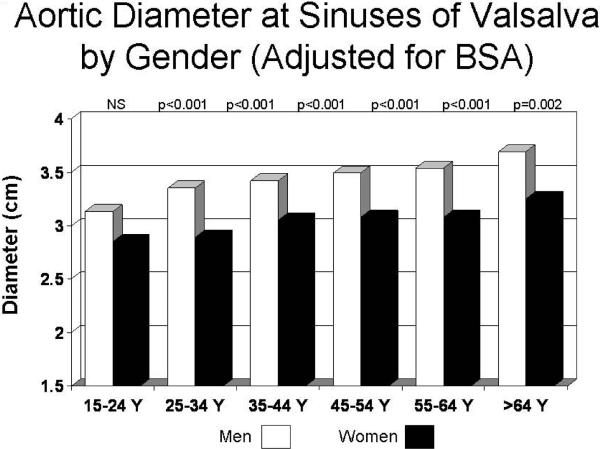

Aortic diameter at the sinuses of Valsalva showed highly significant positive univariate relations with age (r=0.36), weight (r=0.45), height (r=0.14), BSA and BSA0.5 (both r=0.48; all p<0.001). Age and each measure of body size were independently related to sinuses of Valsalva diameter in multiple linear regression models (all p<0.001). In analysis of covariance that adjusted for BSA, mean aortic diameter progressively increased at older ages (p<0.001, Figure 2); similar results were obtained using height as an alternative measure or body size (data not shown). Men had larger mean aortic diameter than women in the entire population (3.34±0.34 cm vs. 2.98 cm, p<0.001). In analysis of covariance adjusted for BSA, aortic diameter tended to be larger in men than women in the youngest age group (15–24 years old) and was significantly greater in men than women in older age groups (Figure 3). Multivariable models increased the coefficient of variation (r2 or R2) for sinuses of Valsalva diameter from 0.23 for BSA alone to 0.36 for BSA and age and to 0.45 when gender was also considered.

Figure 2.

Mean aortic root diameter (vertical axis), adjusted for body surface area, by decade of age (horizontal axis). All differences between successive decades were significant (P ≤0.001) except where indicated to be non-significant (NS).

Figure 3.

Mean aortic root diameter (vertical axis), adjusted for body surface area, in men (open columns) and women (filled columns) by decade of age (horizontal axis). All differences between gender within decades of age were significant (P ≤0.002) except where indicated to be non-significant (NS).

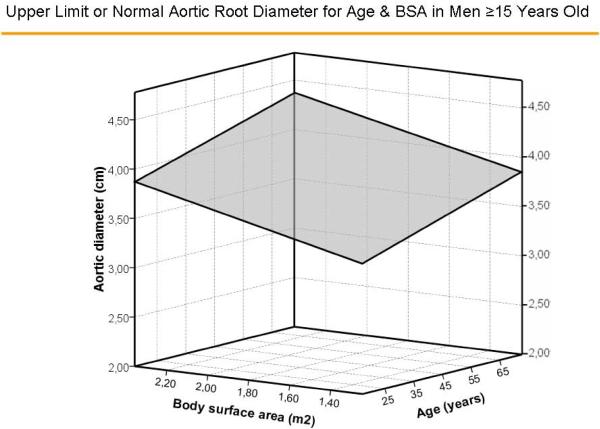

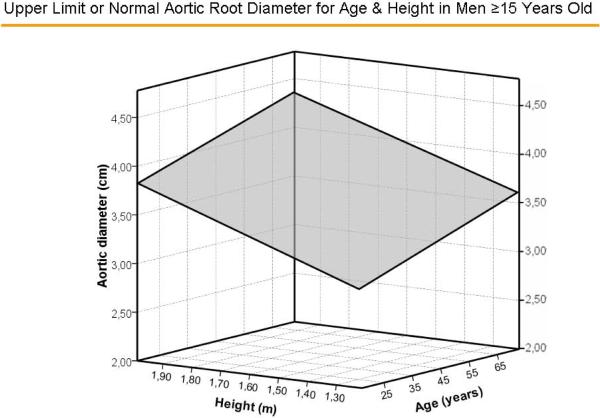

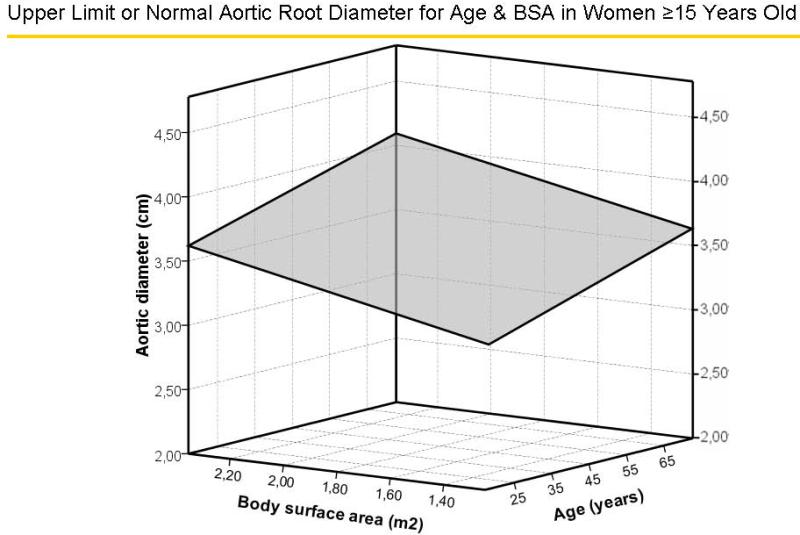

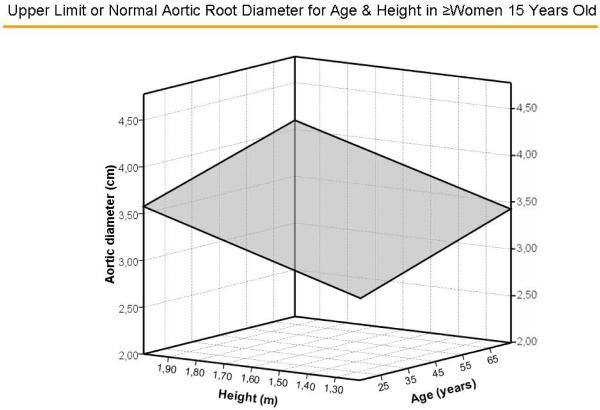

Multivariable models with age and gender yielded similar multiple R values (both = 0.67) with either BSA or height as the measure of body size (Table 1). The standard errors of the estimate, upon which calculation of z-scores is based, were 0.261 and 0.215 cm, respectively. Surfaces representing aortic diameters 1.96 z-scores above the predicted mean value of aortic diameter for age and BSA, and age and height for men are illustrated in Figure 4A and 4B, respectively and for women in Figure 5A and 5B, respectively. There were no significant residual linear relations of age, gender or body size measures with the difference between observed sinuses of Valsalva diameter and values predicted using either BSA or height (all p>0.20). When absolute residuals were considered, only weak relations (r2 =0.010–0.016) were observed. Finally, multiple linear models that additionally considered body mass index did not improve on those using age, gender and either BSA (multiple R = 0.677 vs. 0.674) or height (R = 0.679 vs. 0.674, both=NS).

Table 1.

Multivariable Models for Aortic Root Diameter in Relation to Age, Body Size and Gender

| Model with Body Surface Area: Dependent Variable Aortic Root Diameter (cm) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | B | SE | β | T | p |

|

| |||||

| Intercept | 2.423 | 0.261 | |||

|

| |||||

| Age (decade) | 0.090 | 0.0044 | 0.387 | 20.3 | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| Body Surface Area (m2) | 0.461 | 0.036 | 0.467 | 21.7 | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| Gender: | |||||

| Male | −0.267 | 0.025 | −0.219 | −10.4 | <0.0001 |

| Female | −0.534 | ||||

| Model with Body Height: Dependent Variable Aortic Root Diameter (cm) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | B | SE | β | T | p |

|

| |||||

| Intercept | 1.519 | 0.215 | |||

|

| |||||

| Age (decade) | 0.10 | 0.004 | 0.429 | 25.2 | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| Height (cm) | 0.010 | 0.001 | 0.387 | 14.8 | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| Gender: | |||||

| Male | −0.247 | 0.017 | −0.239 | −10.4 | <0.0001 |

| Female | −0.494 | ||||

Figure 4.

Surfaces representing aortic diameters 1.96 z-scores above the predicted mean value of aortic diameter for age and body surface area (Figure 4A) and age and height (Figure 4B) in men.

Figure 5.

Surfaces representing aortic diameters 1.96z scores above the predicted mean value of aortic diameter for age and body surface area (Figure 5A) and age and height (Figure 5B) in women.

Aortic dilatation can be recognized when the difference between observed sinuses of Valsalva diameter and the value predicted for age, gender and body size >1.96 standard errors of the estimate (0.261 cm for the model with BSA and 0.215 cm for that with height) above the predicted value. For convenience, mild, moderate and severe aortic dilatation can be recognized by positive z-score values from these models of 1.97–3.0, 3.01–4.0 and >4.0, following a previously-reported convention (6).

Multivariable models for aortic annular diameter had similar multiple R values (0.64 and 0.63, respectively) with age, gender and either BSA or height as the body size measure (Table 2). The standard errors of the estimate, upon which calculation of z-scores is based, were 0.113 and 0.070 cm, respectively. There were no significant residual linear relations of age, gender or body size measures with the difference between observed and predicted aortic annular diameter (all p>0.20). Only weak relations (r2 =0.010–0.014) were observed for absolute residuals.

Table 2.

Multivariable Models for Aortic Annular Diameter in Relation to Age, Body Size and Gender

| Model with Body Surface Area: Dependent Variable Aortic Annular Diameter (cm) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | B | SE | β | T | p |

|

| |||||

| Intercept | 1.439 | 0.070 | <0.0001 | ||

|

| |||||

| Age (decade) | 0.02 | 0.003 | 0.138 | 6.2 | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| Body Surface Area (m2) | 0.457 | 0.032 | 0.467 | 14.3 | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| Gender: | |||||

| Male | −0.121 | 0.012 | −0.219 | −9.8 | <0.0001 |

| Female | −0.242 | ||||

| Model with Body Height: Dependent Variable Aortic Annular Diameter (cm) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | B | SE | β | T | p |

|

| |||||

| Intercept | 1.535 | 0.113 | <0.0001 | ||

|

| |||||

| Age (decade) | 0.01 | 0.002 | 0.099 | 4.1 | <0.001 |

|

| |||||

| Height (cm) | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.250 | 7.6 | <0.0001 |

|

| |||||

| Gender: | −0.440 | <0.0001 | |||

| Male | −0.152 | 0.011 | −13.6 | ||

| Female | −0.304 | ||||

Discussion

The present study used systematically performed 2-dimensional echocardiographic measurements of aortic root diameter in a large reference population of adolescents and adults drawn from a variety of population-based samples to clarify strong, independent associations of aortic root size with age, body size and gender.

Previous studies have consistently found increases of aortic root size with older age in adults, by ~0.7 – 1 mm per decade in diverse population, including healthy Japanese adults 20–79 years old (14), Framingham Heart Study participants (15–16), and adult volunteers studied by cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging (17). In contrast, findings have been less consistent among children. In series of 353 and 229 apparently normal children in France and Turkey, aortic root diameter increased with age (18–19). However, in a large U.S. series (n=496) up to age 20, age was not related to aortic root size independent of body size (20). Our finding that mean aortic root diameter increased by 0.9 mm per decade in the multivariable model with BSA as the measure of body size and by 1.0 mm per decade in the model that included height is thus consistent with evidence from most but not all other populations.

Strong relations of aortic diameter with body size have been consistently documented in apparently normal children. In 168 apparently normal children and young adults from Finland, aortic diameters at 8 levels from the annulus to the descending thoracic aorta were more closely correlated with BSA (all r >0.84) than either height or weight (all r ≥0.75)(20). In an M-mode echocardiographic study in 229 normal Turkish children, aged one day to 15 years, aortic root diameters increased with age, weight and BSA (21). Aortic diameter is also strongly related to body size among apparently normal adults, albeit with lower correlation coefficients, due at least in part to the narrower range of body sizes. Several studies have taken allometric considerations into account, in which a linear measure such as aortic root diameter is expected to be directly related to a linear measure of body size such as height but to the square root of second-power variables such as BSA. Strong relations, with r values from ~0.90 to 0.95, have been observed between aortic diameters at the root and at other levels and the square root of BSA (13, 20–21). Our finding of highly significant relations of aortic root diameter with BSA, BSA0.5 and, less closely, height are thus consistent with prior observations. Multivariable regression models using height or BSA had virtually identical R2 values, facilitating their interchangeable use; use of BSA0.5 did not improve our models.

Studies in adults have reported an association of male gender with larger aortic size. In ~4000 Framingham participants, M-mode echocardiographic aortic root measurements by a leading-edge-to-leading-edge technique were 2.4 mm smaller in women than men of comparable age, height, and weight (15). Among 700 healthy Japanese 20–79 years old, echocardiographic aortic root diameter was 3 mm larger in men; multivariate analyses adjusting for body size were not reported (14). Among 129 adults in Thailand, aortic diameters measured from thoracic multidetector computed tomographic images were larger by 1–2 mm in men than women (22).

In contrast, studies in children have not shown a consistent independent association of gender with aortic root diameter. Thus, among 168 apparently normal Finnish children and young adults, there was no gender difference in aortic diameter/BSA (20). Similarly, among subjects <15 years old in the report by Roman et al (4), there was no gender difference in aortic root diameter (p=0.46). Gautier et al. (17), recently showed similar aortic diameter in smaller children of both genders, with larger diameters in larger male than female subjects, suggesting a differential effect of sexual maturation on aortic size between the genders. The result that male gender was associated with 2.7 and 2.5 mm larger mean aortic root diameter in our multivariable models with BSA or height, respectively, and age thus provides a robust estimate of the effect of male gender on aortic root diameter among apparently normal adults.

To compare results of the present study with those of previous reports, one must consider impacts of imaging modality and measurement method on aortic diameter measurements. M-mode echocardiography yields measurements of the antero-posterior aortic root diameter at enddiastole that are 1–2 mm smaller than obtained by 2-dimensional echocardiography (4, 19). Use of 3-dimensional imaging modalities allows alternative measures of aortic diameter. For example, Burman et al. used cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging to measure aortic diameters from cusp to cusp - - approximating the echocardiographic method - - and from cusp to opposite commissure (18). Mean diastolic cusp-commissure dimensions were smaller than cusp-cusp dimensions by 2.6 mm in men and 2.3 mm in women (18). Similarly, among 103 clinically normal adults who underwent retrospectively-gated multidetector computed tomographic angiography (23), aortic diameters measured from mid sinus of Valsalva to opposite commissure were ~2 mm less than values predicted by established echocardiographic nomograms reflecting sinus-to-sinus measurements (4). Another consideration in comparing aortic diameters by different methods is that axial slices in conventional computed tomographic or magnetic resonance imaging scans may be obliquely oriented to the axis of the aorta, resulting in overstatement of aortic diameter and area by up to 15% (24).

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by grants RO1-HL55673, U01-HL54496, U01-HL65521 and M10RR0047-34 from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD. There are no relationships with industry regarding this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Roman MJ, Devereux RB, Niles NW, Hochreiter C, Kligfield P, Sato N, Spitzer MC, Borer JS. Aortic root dilatation as a cause of isolated, severe aortic regurgitation: prevalence, clinical and echocardiographic patterns, and relation to left ventricular hypertrophy and function. Ann Intern Med. 1987;106:800–807. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-106-6-800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lebowitz NE, Bella JN, Roman MJ, Liu JE, Fishman DP, Paranicas M, Lee ET, Fabsitz RR, Welty TK, Howard BV, Devereux RB. Prevalence and correlates of aortic regurgitation in American Indians: The Strong Heart Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:461–467. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00744-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim SY, Martin N, Hsia EC, Pyeritz RE, Albert DA. Management of aortic disease in Marfan syndrome: A decision analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:749–755. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.7.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roman MJ, Devereux RB, Kramer-Fox R, O'Loughlin J. Two-dimensional echocardiographic aortic root dimensions in children and adults: biologic determinants and normal limits. Am J Cardiol. 1989;64:507–512. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(89)90430-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Paepe A, Devereux RB, Dietz HC, Hennekam RCM, Pyeritz RE. Revised diagnostic criteria for the Marfan syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1996;62:417–426. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19960424)62:4<417::AID-AJMG15>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Pellikka PA, Picard MH, Roman MJ, Seward J, Shanewise J, Solomon SD, Spencer KT, St. John Sutton M, Stewart WJ. Members of the Chamber Quantification Writing Group. Recommendations for Chamber Quantification. A report from the American Society of Echocardiography's Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18:1440–1463. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chinali M, de Simone G, Roman MJ, Lee ET, Best LG, Howard BV, Devereux RB. Impact of obesity on cardiac geometry and function in a population of adolescents: The Strong Heart Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:2267–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drukteinis JS, Roman MJ, Fabsitz RR, Lee ET, Best LG, Russell M, Devereux RB. Cardiac and systemic hemodynamic characteristics of hypertension and prehypertension in adolescents and young adults: The Strong Heart Study. Circulation. 2007;115:221–227. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.668921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aguilar D, Hallman DM, Piller LB, Klein BE, Klein R, Devereux RB, Arnett DK, Gonzalez VH, Hanis C. Adverse association between diabetic retinopathy and cardiac structure and function. Am Heart J. 2009;157:563–568. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fox ER, Klos KL, Penman AD, Blair GJ, Blossom BD, Arnett DK, Devereux RB, Samdarshi T, Boerwinkle E, Mosley TH., Jr. Heritability and genetic linkage of left ventricular mass, systolic and diastolic function in hypertensive African Americans (From the GENOA Study) Am J Hypertens. 2010;23:870–875. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2010.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palmieri V, Bella JN, Arnett DK, Roman MJ, Oberman A, Kitzman DW, Hopkins PN, Paranicas M, Rao DC, Devereux RB. Aortic root dilatation at sinuses of Valsalva and aortic regurgitation in hypertensive and normotensive subjects: The HyperGEN study. Hypertension. 2001;37:1229–1235. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.5.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DuBois D, DuBois EF. A formula to estimate the approximate surface area if height and weight be known. Arch Intern Med. 1916;17:863–871. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sluysmans T, Colan SD. Theoretical and empirical derivation of cardiovascular allometric relationships in children. J Appl Physiol. 2005;99:445–457. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01144.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daimon M, Watanabe H, Abe Y, Hirata K, Hozumi T, Ishii K, Ito H, Iwakura K, Izumi C, Matsuzaki M, Minagoe S, Abe H, Murata K, Nakatani S, Negishi K, Yoshida K, Tanabe K, Tanaka N, Tokai K, Yoshikawa J. Normal values of echocardiographic parameters in relation to age in a healthy Japanese population: the JAMP study. Circulation J. 2008;72:1859–1866. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-08-0171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vasan RS, Larson MG, Levy D. Determinants of echocardiographic aortic root size: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 1995;91:734–740. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.3.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vasan RS, Larson MG, Benjamin EJ, Levy D. Echocardiographic reference values for aortic root size” the Framingham Heart Study. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1995;8:793–800. doi: 10.1016/s0894-7317(05)80003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burman ED, Keegan J, Kilner PJ. Aortic root measurement by cardiovascular magnetic resonance: specification of planes and lines of measurement and corresponding normal values. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2008;1:104–113. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.108.768911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gautier M, Detaint D, Fermanian C, Aegerter P, Delorme G, Arnoult F, Milleron O, Raoux F, Stheneur C, Boileau C, Vahanian A, Jondeau G. Nomograms for aortic root diameters in children using two-dimensional echocardiography. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105:888–894. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kervancioglu P, Kervancioglu M, Tuncer CM. Echocardiographic study of aortic root diameter in healthy children. Saudi Med J. 2006;27:27–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pettersen MD, Du W, Skeens ME, Humes RA. Regression equations for calculation of Z scores of cardiac structures in a large cohort of healthy infants, children, and adolescents: An echocardiographic study. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2008;21:922–934. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poutanen T, Tikanoja T, Sairanen H, Jokinen E. Normal aortic dimensions and flow in 168 children and young adults. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2003;23:224–229. doi: 10.1046/j.1475-097x.2003.00501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Euathrongchit J, Deesuwan P, Kuanprasert S, Woragitpoopol S. Normal thoracic aortic diameter in Thai people by multidetector computed tomography. J Med Assoc Thai. 2009;92:236–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin FY, Devereux RB, Roman MJ, Meng J, Jow VM, Jacobs A, Weinsaft JW, Shaw LJ, Berman DS, Gilmore A, Callister TQ, Min JK. Assessment of the thoracic aorta by multidetector computed tomography: age- and sex-specific reference values in adults without evident cardiovascular disease. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2008;2:298–308. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mendoza DD, Kochar M, Devereux RB, Basson CT, Min JK, Holmes K, Dietz HC, Milewicz DM, LeMaire SA, Pyeritz RE, Bavaria JE, Maslen CL, Song H, Kroner BL, Eagle KA, Weinsaft JW. GenTAC (National Registry of Genetically Triggered Thoracic Aortic Aneurysms and Cardiovascular Conditions) Study Investigators. Impact of image analysis methodology on diagnostic and surgical classification of patients with thoracic aortic aneurysms. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92:904–912. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.03.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]