Abstract

Nuclear epigenetics of the mammalian brain is modified during aging. Little is known about epigenetic modifications of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA). We analyzed brain samples of 4- and 24-month-old mice and found that aging decreased mtDNA 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) but not 5-methylcytosine (5mC) levels in the frontal cortex but not the cerebellum. Transcript levels of selected mtDNA-encoded genes increased during aging in the frontal cortex only. Aging affected the expression of enzymes involved in 5-methylcytosine and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine synthesis (mitochondrial DNA methyltransferase 1 [mtDNMT1] and ten-eleven-translocation [TET]1-TET3, respectively). In the frontal cortex, aging decreased mtDNMT1 messenger RNA (mRNA) levels without affecting TET1-TET3 mRNAs. In the cerebellum, TET2 and TET3 mRNA content was increased but mtDNMT1 mRNA was unaffected. Using Western immunoblotting of samples from primary neuronal cultures, we found TET immunoreactivity in the mitochondrial fraction. At the single cell level, TET immunoreactivity was detected in the nucleus and in the perinuclear/intraneurite areas where it frequently colocalized with a mitochondrial marker. Our results demonstrated the presence and susceptibility to aging of mitochondrial epigenetic mechanisms in the mammalian brain.

Keywords: Mitochondrial epigenetics, Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), Ten-eleven-translocation (TET), DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1), 5-Hydroxym-ethylcytosine (5hmC), 5-Methylcytosine (5mC), Brain, Frontal cortex, Cerebellum, Aging

1. Introduction

Epigenetic mechanisms are emerging as major pathways that neurons use in the adaptive (neuroplastic) regulation of gene expression. Despite the recent increased interest in studies of epigenetic mechanisms in the physiology and pathology of the central nervous system (hence the term neuroepigenetics; Day and Sweatt, 2011), the focus of that research has been limited to only one compartment of cellular DNA, the nucleus. Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) of brain cells has not been extensively studied for epigenetic modifications such as 5-methylcytosine (5mC) and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) and the field of mitochondrial neuroepigenetics is presently in its nascent form (Manev et al., 2012).

Our current understanding of the nuclear neuroepigenetic system stresses its complexity, which includes a number of modifiers (enzymes and regulatory proteins) of chromatin (comprising nuclear DNA and proteins such as histones) (for review see Riccio, 2010). Because mitochondria do not contain histones and their DNA is not constrained/regulated through chromatin remodeling (instead, mtDNA is associated with different proteins into aggregates called nucleoids; Rebelo et al., 2011), the functional significance of mitochondrial epigenetics has typically been dismissed.

In the nucleus, DNA is methylated by an addition of a methyl group to the 5= position of the base cytosine to generate 5mC. A critical step in this process is mediated by the action of three DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs)—DNMT1 (the maintenance enzyme) and DNMT3a and DNMT3b (which have the capacity to methylate DNA de novo). Although the existence of a mammalian mitochondrion-specific DNMT has long been inferred (Vanyushin and Kirnos, 1977), only recently was an isoform of DNMT1, mitochondrial DNMT1 (mtDNMT1), characterized that appears to be essential for mammalian mtDNA methylation (Shock et al., 2011). These authors also reported that mtDNA contains a significant amount of 5hmC. The exact mechanism of mitochondrial 5hmC synthesis has not as yet been clarified. For example, no data are available on whether the family of ten-eleven-translocation (TET) enzymes (TET1, TET2, and TET3), which are involved in the nuclear conversion of 5mC into 5hmC (Iyer et al., 2009; Tahiliani et al., 2009), is operative in the mitochondrion.

Brain aging and aging-associated neurodegenerative pathologies are now becoming understood as biological processes that both contribute and are susceptible to epigenetic mechanisms (Chouliaras et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2009; Mastroeni et al., 2011; Penner et al., 2010). In postmortem human brain samples, methylation of nuclear DNA (ncDNA) appears to positively correlate with aging (Hernandez et al., 2011; Siegmund et al., 2007). Similarly, ncDNA 5hmC content, which appears to be particularly abundant in the cerebellum and cortex (Kriaucionis and Heintz, 2009; Münzel et al., 2011) and 5hmC localization in ncDNA extracted from human and mouse brain is highly dynamic and susceptible to aging-associated modifications (Münzel et al., 2011; Song et al., 2011; Szulwach et al., 2011).

All currently available published work on epigenetic mechanisms in brain aging refers to nuclear mechanisms. Despite the significant body of knowledge regarding the interactions between aging and mitochondria, including in the brain (Cheng et al., 2010; Swerdlow, 2011; Tranah, 2011), mtDNA has mostly been investigated with respect to mtDNA mutations, mtDNA damage, and the effects of mitochondria on nuclear epigenetic mechanisms (Greaves et al., 2012; Wallace and Fan, 2010) and to the best of our knowledge, no studies of brain aging have explored epigenetic mechanisms in mitochondria. In this work, we investigated the mitochondrial epigenetics of the mammalian central nervous system using a mouse model of aging and mouse primary neurons in culture. The cerebellum has historically been considered the primary brain region for 5hmC research (Kriaucionis and Heintz, 2009). Hence, our studies were performed in the cerebellum and for comparison in the frontal cortex samples.

2. Methods

2.1. Animals

Whole brains of 5 adult (4 months) and 5 old (24 months) C57BL6 male mice were obtained from the Aged Rodent Tissue Bank (National Institute on Aging, Bethesda, MD, USA). The old mice used in this study were among 80% surviving (Turturro et al., 1999). The postmortem time to freezing for the brain tissue did not differ between the groups (adult, 140 ± 12 seconds; old, 149 ± 5 seconds). The frontal cortex (coronal sections; bregma, 3.20–1.54 mm; Paxinos and Franklin, 2001) and the cerebellum (coronal sections; bregma, −4.96 mm to −8.24 mm) were used for analyses. Adult C57BL6 mice (4-month-old; used to obtain brain tissue for immunofluorescence) and mouse pups (for preparation of cerebellar neuronal cultures) were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Animal procedures were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes on Health guidelines for the use of experimental animals and were approved by the University of Illinois Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.2. Neuronal cultures

Primary cultures of cerebellar granule neurons (CGNs) were prepared from 5-day-old pups as previously reported (Imbesi et al., 2009). Briefly, 0.6 million/mL CGNs were cultured in a serum-free neurobasal medium with B27 supplement (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for 14 days in poly-D-lysine coated 3.5-cm diameter dishes (for Western blot assay) or on 12-mm diameter round cover glasses in 12-well plates (for immunofluorescence assay).

2.3. Isolation of mitochondria and extraction of mtDNA

Mitochondrial DNA was extracted according to a commercial protocol (G-Biosciences, St. Louis, MO, USA). In brief, samples were gently homogenized by straight strokes with a pestle in 500-µL cold cell lysis buffer and then centrifuged at 700g for 10 minutes to pellet the nucleus. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube and centrifuged again at 12,000g for 15 minutes to pellet mitochondria. To isolate mtDNA, the pellet was resuspended in mitochondrial lysis buffer with proteinase K and incubated at 37 °C overnight. Thereafter, DNA was extracted with isopropanol, rinsed with ethanol, and dissolved in a Tris-ethylenedi-aminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) buffer.

2.4. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) of DNA 5hmC and 5mC contents

The 5hmC content of mtDNA and ncDNA was measured by the Hydroxymethylated DNA quantification kit (Epigen-tek, Brooklyn, NY, USA). Briefly, 100 ng of respective DNA was bound to a 96-well plate. The hydroxymethylated fraction of DNA was detected using its respective capture and detection antibodies and quantified colorimetrically by reading the absorbance at 450 nm in a microplate spectrophotometer (Bio-Rad, Model 550, Hercules, CA, USA). For measurement of 5mC contents, an alternative Methylated DNA quantification kit from Epigentek was utilized. The results are expressed in units calculated according to the manufacturer’s manual.

2.5. Quantitative real time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) messenger RNA (mRNA) assay

Total RNA was extracted from brain samples with TRI-zol Reagent (Invitrogen) and treated with DNase (Ambion, Inc., Austin, TX, USA). RNA was reverse transcribed with M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). The quantitative real time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed on Stratagene Mx3005P QPCR System (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) machine with Maxima SYBR Green/ROX Master Mix (Fermentas, Inc., Glen Burnie, MD, USA). Data were normalized against a cyclophilin internal control and presented as a coefficient of variation, calculated with the formula 2−[ΔCt(target)−ΔC(input)] as previously described (Dzitoyeva et al., 2009). A “no template control” was included as a negative control in the quantitative PCR (qPCR) runs. As a positive control, the specificity of primers was confirmed prior to experiments; this included the confirmation of the expected size single PCR products, serial dilutions of templates, and sequencing of the PCR products. Cyclopilin was selected as an internal control after confirming that the cyclophilin mRNA levels measured against beta actin and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) as controls were not affected by aging in our samples (Supplementary Table 1). The list of primers used is reported in Supplementary Table 2. The regions specific to mtDNMT1 and the total DNMT1 transcripts were amplified and their expected sizes are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1; in the mouse brain, the mtDNMT1 signal was approximately 1 tenth of the total DNMT1 signal.

2.6. Sequence-specific mtDNA 5hmC assay

The 5hmC modifications of mtDNA were quantified using a glucosyltransferase assay that involves an enzymatic restriction digest combined with qPCR; the principle of the method described and visualized in Davis and Vaisvila (2011). We have modified this assay by selecting a different set of restriction enzymes, i.e., CviAII (CATG recognition site) and CviQI (GTAC recognition site) (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA). Both enzymes are insensitive to cytosine methylation and hydroxymethylation (CviAII is only partially, about 25% sensitive to 5hmC). After sample glucosylation, which occurs only on 5hmC but not C or 5mC, the above sites are fully protected from the action of the 2 enzymes (a measure of hydroxymethylation). The target DNA sequence (digested and glucosylated) is amplified and measured by qPCR. Mouse mtDNA (NC_005089) contains 41 CviAII and 23 CviQI recognition sites. We analyzed a sequence of the D-loop region and arbitrary selected the ND2 and ND5 gene regions. These sequences were selected based on their susceptibility to the enzyme digest and no other regions were analyzed in this study. For glucosylation reaction, DNA was glucosylated with T4 phage β-glucosyltransferase (T4-BGT) (New England Biolabs), which specifically transfers the glucose moiety of uridine diphosphoglucose (UDP-Glc) to the 5hmC residues. Glucosylated DNA was digested with CviAII and CviQI enzymes in separate reactions and an aliquot was used in qPCR. As an input control, we used equal amounts of undigested DNA. The qPCR assay (as described above for mRNA) was performed with the following primers: ND2 gene region (CviAII 2 sites, CviQI 1 site) 5′-ccacgatcaactgaagcagcaaca-3′ and 5′-aagtgctatgaatataggggctgt-3′; ND5 gene region (CviAII 2 sites, CviQI 2 sites) 5′-gcatcggagacatcggattcatt-3′ and 5′-tgcgtgggtacagatgtgtaggaa-3′; D-loop (CviAII 5 sites, CviQI 5 sites) 5′-accagcacccaaagctggtattct-3′ and 5′-gttgttggtttcacggaggatggt-3′; 5′-agacatctcgatggtatcgggtct-3′ and 5′-gggtttggcattaagaggaggg-3′.

As a simpler alternative, we complemented the above method with an assay of 5hmC mtDNA modifications employing a set of restriction enzymes that are known to be sensitive to 5hmC modifications albeit with a variable selectivity against 5-mC modifications. This assay was performed as described above with the exception of the glucosylation step. Enzymes used (sensitive to 5hmC in the indicated non-CpG recognition sites; The Restriction Enzyme Database-rebase.neb.com): AluI (AGCT), MnlI (CCTC), HaeIII (GGCC), and FatI (CATG). The list of primers used to amplify the corresponding targeted mtDNA sequences are shown in Supplementary Table 3. Similar results were obtained with either purified mtDNA (Table 1) or a mixture of ncDNA and mtDNA (Supplementary Table 4).

Table 1.

mtDNA 5hmC content in the frontal cortex of adult and old mice assessed with a restriction digest assay

| mtDNA target | 4-Month-old | 24-Month-old |

|---|---|---|

| MnlI digest | ||

| ND2 | 0.63 ± 0.090 | 0.40 ± 0.050** |

| ND4L/ND4 | 0.15 ± 0.010 | 0.10 ± 0.010** |

| ND4 | 1.01 ± 0.110 | 0.54 ± 0.040** |

| ND5 | 0.11 ± 0.010 | 0.06 ± 0.010** |

| COX3 | 0.77 ± 0.080 | 0.43 ± 0.040 |

| tRNAs A, N, C, Y | 0.66 ± 0.120 | 0.29 ± 0.030* |

| HaeIII digest | ||

| ND2 | 0.23 ± 0.030 | 0.13 ± 0.012** |

| ND5 | 0.15 ± 0.017 | 0.14 ± 0.014 |

| COX1 | 0.16 ± 0.013 | 0.11 ± 0.008* |

| AluI digest | ||

| ND4 | 0.12 ± 0.007 | 0.07 ± 0.010** |

| ND5 | 0.17 ± 0.020 | 0.14 ± 0.020 |

| COX3 | 0.15 ± 0.014 | 0.07 ± 0.004*** |

| ATP6 | 0.59 ± 0.110 | 0.35 ± 0.030* |

| tRNAs A, N, C, Y | 0.11 ± 0.020 | 0.08 ± 0.010 |

| FatI digest | ||

| ND2 | 0.63 ± 0.070 | 0.32 ± 0.090* |

| ND5 | 0.55 ± 0.120 | 0.38 ± 0.050 |

| COX3 | 0.23 ± 0.030 | 0.14 ± 0.020* |

mtDNA was extracted from isolated mitochondria, digested with the indicated restriction enzymes, and assayed with mtDNA-targeted polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primers as described in the text. Results are expressed in units (mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM]; n = 5).

Key: 5hmC, 5-hydroxymethylcytosine; mtDNA, mitochondrial DNA; tRNA,.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

2.7. Western immunoblotting

Proteins for Western blot assays were isolated from nuclear and mitochondrial pellets (prepared as described above for isolation of mitochondria), which were lysed in the mitochondrial lysis buffer supplemented with protease inhibitors for 30 minutes on ice. Protein concentration was measured using the BCA protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) and 30-µg protein samples were processed on a 7.5% (wt/vol) Tris-HCl gel and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies. The antibodies used were goat anti-TET1 (1:500, Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA, USA); rabbit anti-TET2 (1:500, Santa Cruz); mouse anticytochrome c oxidase Subunit I (MTCO1, mitochondrial marker; 1:1000, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA); and mouse anti-DNA methyltransferase 3a (DNMT3a, 1:1000, Imgenex, San Diego, CA, USA). Thereafter, the membranes were incubated with appropriate horseradish-peroxidaselinked secondary antibodies (1:1000, Amersham, Piscataway, NJ, USA; and Santa Cruz). An ECL plus kit (Amersham) was used for band visualization.

2.8. Laser capture microdissection

Coronal sections (30 µm thick) of the cerebellum were mounted on polyethylene tetraphthalate-membrane slides (Leica, Bannockburn, IL, USA) for laser capture microdissection (LCM) as previously described (Chen et al., 2010). Sections were thawed at room temperature for 30 seconds, washed briefly in diethylpyrocarbonate-treated water and stained with hematoxylin for 1 minute, 0.1% NH4OH eosin solution for 30 seconds, then dehydrated in a series of ethanol baths. Immediately after dehydration, laser capture microdissection was performed using a laser capture microscope (Leica). The Purkinje cell layer (approximately 2 mm2 tissue per animal) was selectively cut into plastic tubes.

2.9. Immunocytofluorescence and confocal microscopy

The CGNs on the cover glasses were fixed for 15 minutes in 4% (vol/vol) formaldehyde. Cells were treated with 1N HCl for 15 minutes and incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies in 10% donkey serum and 0.25% Triton X-100. The primary antibodies used were rabbit anti-TET2 (1:200, Santa Cruz) and mouse anti-mtCOX1 (MTCO1; 1:200, Abcam). For secondary detection, we used fluorescein-conjugated donkey anti-mouse and rhodamine-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit (1:200, Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA) antibodies. Cell nuclei were counterstained with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA, USA). Laser scanning confocal micrographs were captured using an LSM 510 meta microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) with a 100× objective lens. The scanning of our single cell layer in culture was performed at increments of 0.5 µm. For visualizing the localization of 5hmC in the mouse brain, 30 µm sagittal brain sections of 4-month old C57BL/6 mice were cut after a lethal anesthesia followed by transcardial perfusion and fixation (4% formaldehyde). Sections were incubated with rabbit anti-5hmC (1:200, Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and mouse anti-calbindin 28-kDa protein (CaBP-28; 1:1000, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) antibodies and processed following the above protocol. As a negative control, sections were processed in the absence of the primary antibody—no staining was observed (not shown). Images were captured using a fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss) equipped with a 5× objective lens.

2.10. Statistical analysis

For statistical analysis, we used SPSS software (version 12.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Data were analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by an independent sample t test. Results are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). The p < 0.05 values were accepted as statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Effect of aging on global 5hmC and 5mC content in mtDNA extracted from the frontal cortex and the cerebellum

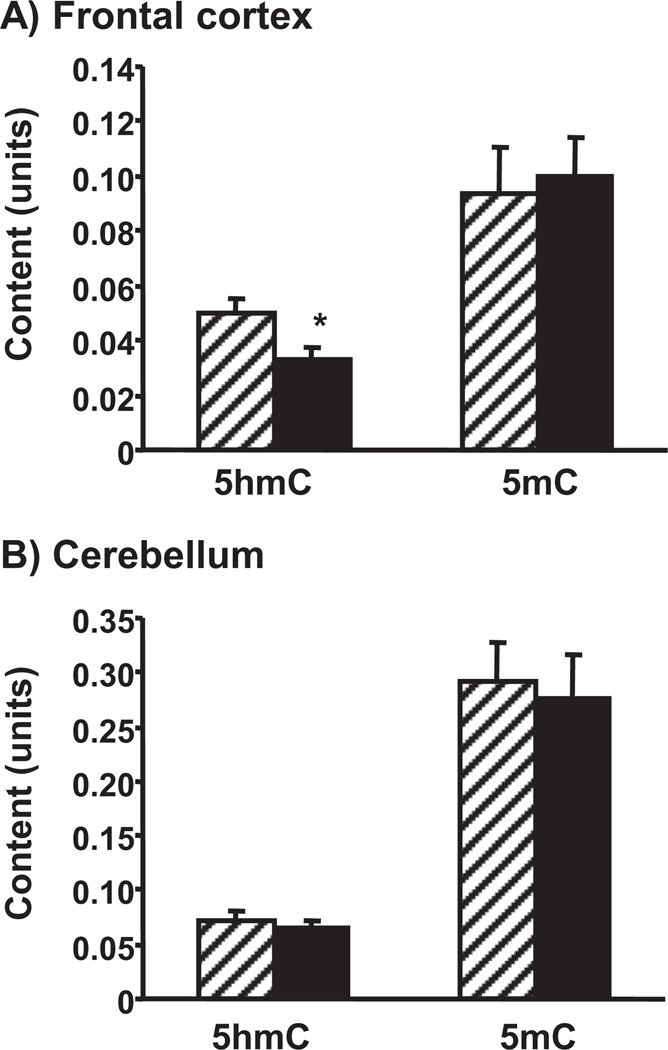

To investigate whether aging has an impact on epigenetic markers in the brain mtDNA, we isolated mitochondria from the frontal cortex and the cerebellum of adult and old mice, extracted mtDNA, and analyzed the samples with 5hmC and 5mC ELISA-based assays, respectively. Fig. 1 shows that aging altered, i.e., decreased, only 5hmC mtDNA content and only in the frontal cortex. We did not detect any changes in the content of mtDNA 5mC due to aging (Fig. 1). In addition, we evaluated the global ncDNA content of 5mC and 5hmC in samples extracted from the frontal cortex and the cerebellum of adult and old mice and found no significant differences (Supplementary Table 5).

Fig. 1.

Effect of aging on global 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) and 5-methylcytosine (5mC) content in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) extracted from isolated mitochondria from the mouse (A) frontal cortex and (B) cerebellum. Mitochondria of 4-month-old (striped bars) and 24-monthold (filled bars) mice were isolated, their DNA was extracted and equal amounts of mtDNA were analyzed with 5hmC and 5mC enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) assays. Results are expressed in units (mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM]; n = 5; * p < 0.05 compared to the corresponding 4-month-old group).

3.2. Effect of aging on sequence-specific 5hmC modifications of mtDNA extracted from the frontal cortex and the cerebellum

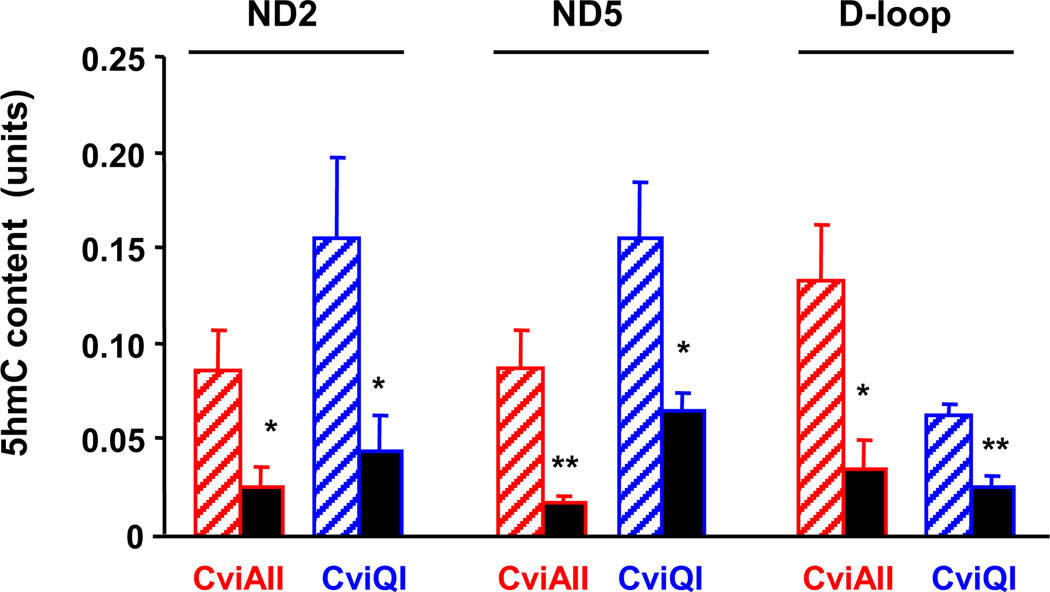

To further investigate the observed aging-associated decrease in the global 5hmC content of cortical mtDNA, we employed a modified glucosyltransferase assay (Davis and Vaisvila, 2011) to determine the 5hmC status of selected sequences in mtDNA. Mouse mitochondria contain a 16,295 base pairs (bp) (Cardon et al., 1994) circular double-stranded mtDNA that encodes 13 polypeptides—members of the oxidative phosphorylation complexes (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide [NADH] dehydrogenase subunits ND1–ND6 and ND4L; cytochrome c oxidases COX1–COX3; adenosine triphosphate [ATP] synthase 6 [ATP6]; ATP synthase 8 [ATP8]; and cytochrome b [CYTB]; for review see Falkenberg et al., 2007], 2 ribosomal RNAs, and 22 transfer RNAs. We analyzed a sequence of the regulatory D-loop region and 2 arbitrarily selected gene regions (ND2 and ND5). Considering the underrepresentation of CpG dinucleotides in mtDNA (Cardon et al., 1994) we did not restrict our assay to these sequences. A glucosyltransferase assay based on 2 enzymes (CviAII and CviQI) revealed that the content of 5hmC modifications in the selected 3 mtDNA sequences was significantly reduced in the frontal cortex of old versus adult mice (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Effect of aging on 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC) content in selected mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) sequences in the frontal cortex. Brain samples were obtained from 4-month-old (striped bars) and 24-month-old (filled bars). Mitochondria were isolated and their DNA was extracted. The content of 5hmC in non-CpG sequences of ND2 and ND5 genes and in the D-loop was measured using a glucosyltransferase assay combined with CviAll and CviQI enzymes. Results are expressed in units (mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM]; n = 5; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01 compared with the corresponding 4-month-old group).

As a simpler alternative to the glucosyltransferase assay, and also to investigate mtDNA 5hmC status in non-CpG sequences on a broader scale, we complemented the above method with an assay employing a set of restriction enzymes that are known to be sensitive to 5hmC modifications, albeit with a variable selectivity against 5mC. Also this assay confirmed that the majority of targeted sequences of DNA extracted from the isolated mitochondria of the frontal cortex of old mice contained significantly less 5hmC compared with samples from adult mice (Table 1). Similar results were obtained when mitochondrial sequences were analyzed in total DNA extracts, i.e., without prior isolation of mitochondria (Supplementary Table 4). Analysis of mtDNA obtained from isolated mitochondria of cerebellar samples did not find significant differences between old and adult mice (Supplementary Table 6).

3.3. mtDNA transcription in brain regions of adult and old mice

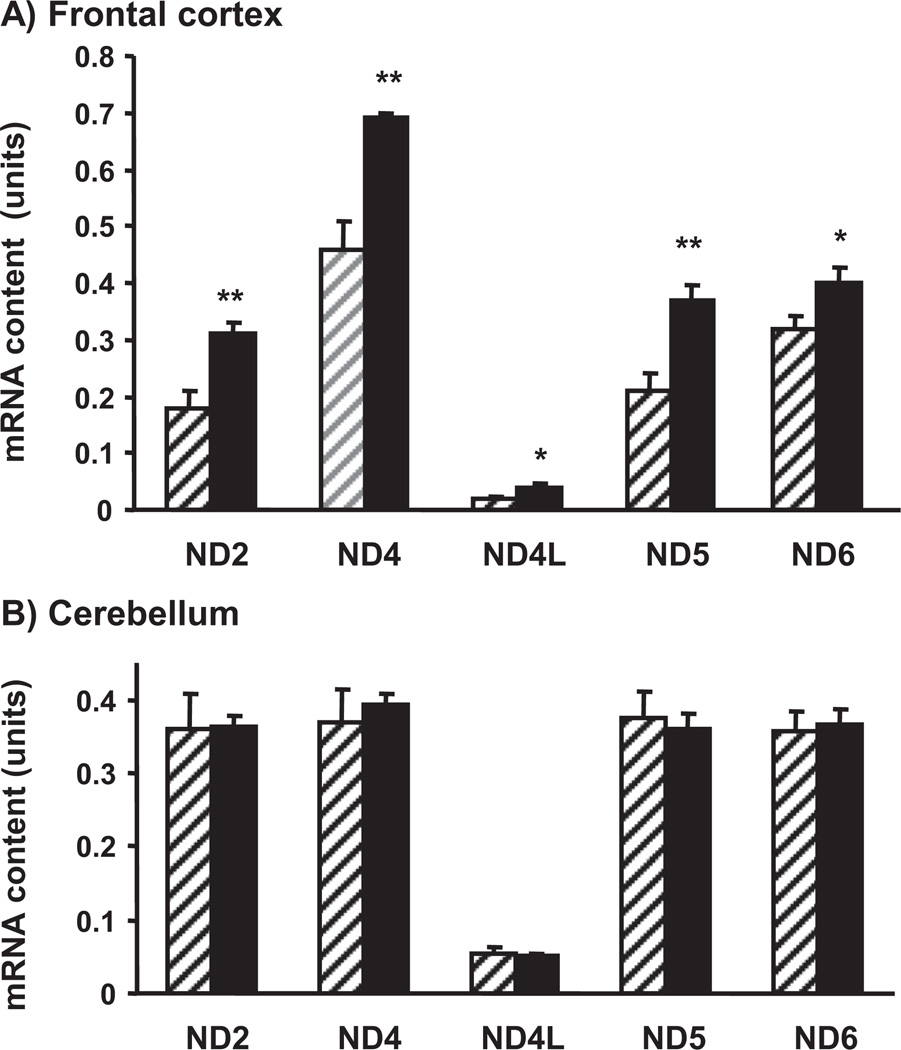

We used frontal cortex and cerebellar samples from adult and old mice to evaluate the effect of aging on mtDNA transcription, i.e., mRNA contents of a number of mtDNA-encoded NADH dehydrogenase subunits (ND2, ND4, ND4L, ND5, and ND6). All targeted transcripts were increased in the frontal cortex of old versus adult mice (Fig. 3A) whereas no significant differences were observed between the 2 age groups in the cerebellum (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Effect of aging on mRNA content of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA)-encoded genes in the frontal cortex (A) and the cerebellum (B). A quantitative real time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) assay was used with brain samples of 4-month-old (striped bars) and 24-month-old (filled bars) mice. Results are expressed in units (mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM]; n = 5; * p < 0.05).

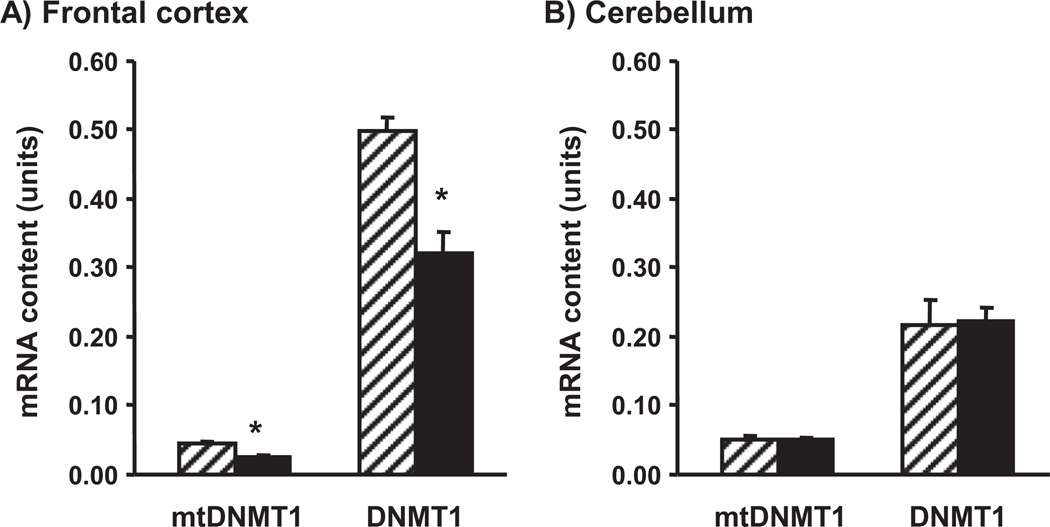

3.4. Effect of aging on mRNA content for mtDNMT1, total DNMT1, TET1, TET2, and TET3 in the frontal cortex and the cerebellum of adult and old mice

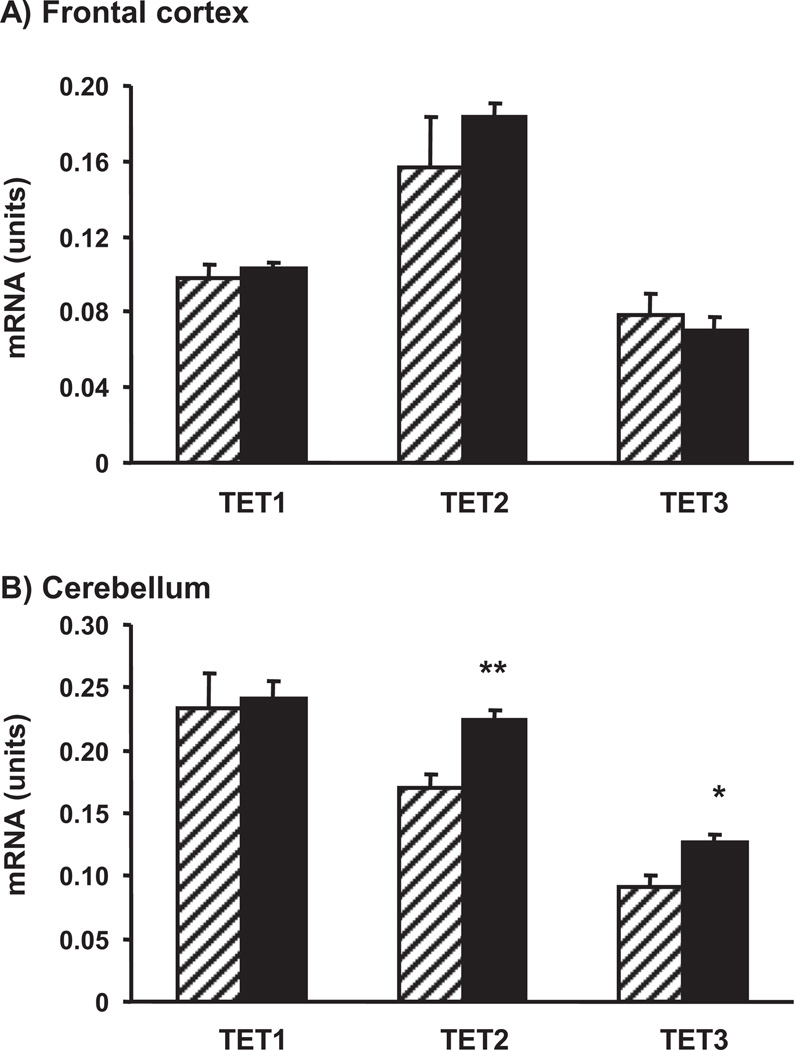

Two sets of enzymes, DNMTs and TETs, play a major role in the synthesis of 5mC and 5hmC, respectively. We investigated whether the transcript amounts for these enzymes differ in brain regions of old versus adult mice. For the first time, we documented the presence of mtDNMT1 transcript in the mouse brain (Supplementary Fig. 1). A quantitative assay revealed that both mtDNMT1 and total DNMT1 mRNA levels are significantly decreased in the frontal cortex and unaltered in the cerebellum of old versus adult mice (Fig. 4). On the other hand, in the frontal cortex we did not find significant differences between the 2 age groups in the content of TET1, TET2, and TET3 mRNAs. However, in the cerebellum, TET2 and TET3 (but not TET1) mRNA content was significantly increased in old versus adult mice (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4.

Effect of aging on mitochondrial DNA methyltransferase 1 (mtDNMT1) and total DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) mRNA content in the frontal cortex (A) and the cerebellum (B). A qRT-PCR assay was used with brain samples of 4-month-old (striped bars) and 24-month-old (filled bars) mice. Results are expressed in units (mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM]; n = 5; * p < 0.05).

Fig. 5.

Effect of aging on ten-eleven-translocation (TET)1, TET2, and TET3 mRNA content in the frontal cortex (A) and the cerebellum (B). A quantitative real time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) assay was used with brain samples of 4-month-old (striped bars) and 24-month-old (filled bars) mice. Results are expressed in units (mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM]; n = 5; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01).

3.5. Mitochondrial localization of TET proteins in primary CGN cultures

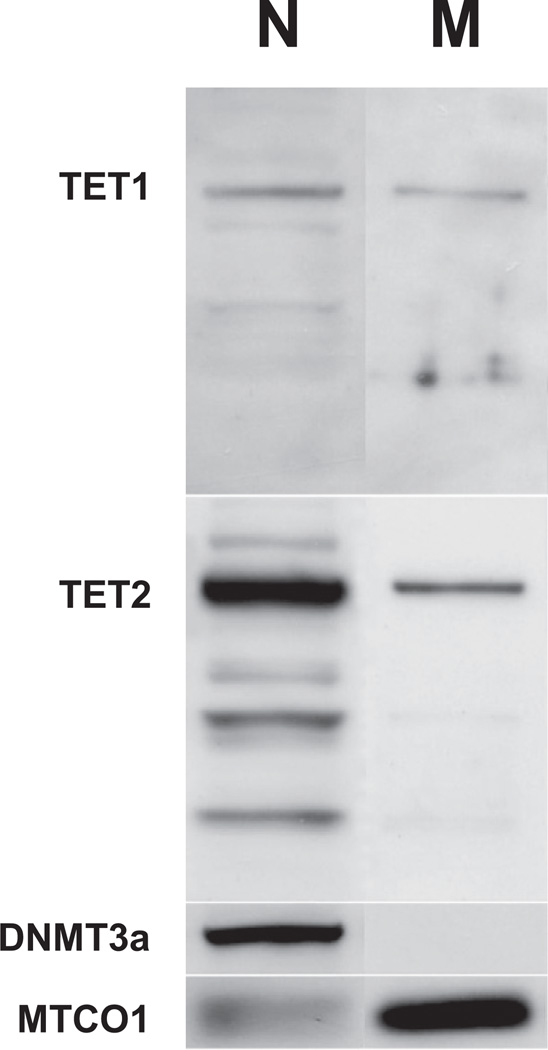

TET proteins (enzymes) play a crucial role in 5hmC synthesis in the nucleus but no data are available on whether they may be operative in the mitochondrion. Because CGNs can be grown in vitro in preparations devoid of significant contamination by other cell types (Favaron et al., 1988), we selected CGN cultures to investigate the putative presence of TET proteins in mitochondria. We used Western immunoblotting with TET1 and TET2 antibodies (the available TET3 antibodies did not recognize a specific target in our mouse brain samples) to investigate nuclear and mitochondrial protein extracts for the presence of these enzymes. We found evidence for a TET1 and TET2 presence not only in the nucleus but also in the mitochondrial fraction. As a control for the purity of our mitochondrial preparation, a DNMT3a signal was confirmed in the nucleus but was not found in the mitochondria (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Western blot detection of ten-eleven-translocation (TET)1 and TET2 immunoreactive proteins in mitochondrial fraction of cerebellar granule neurons (CGNs). Nuclear (N) mitochondrial (M) samples were prepared from primary cultures of CGNs. Note the presence of TET1 and TET2 immunobands in both nuclear and mitochondrial fractions. A nuclear DNA methyltransferase (DNMT)3a immunoreactivity was found in the nuclear fraction only (evidence for the purity of the mitochondrial preparation) and a mitochondrial marker MTCO1 was strongly present in the mitochondrial fraction.

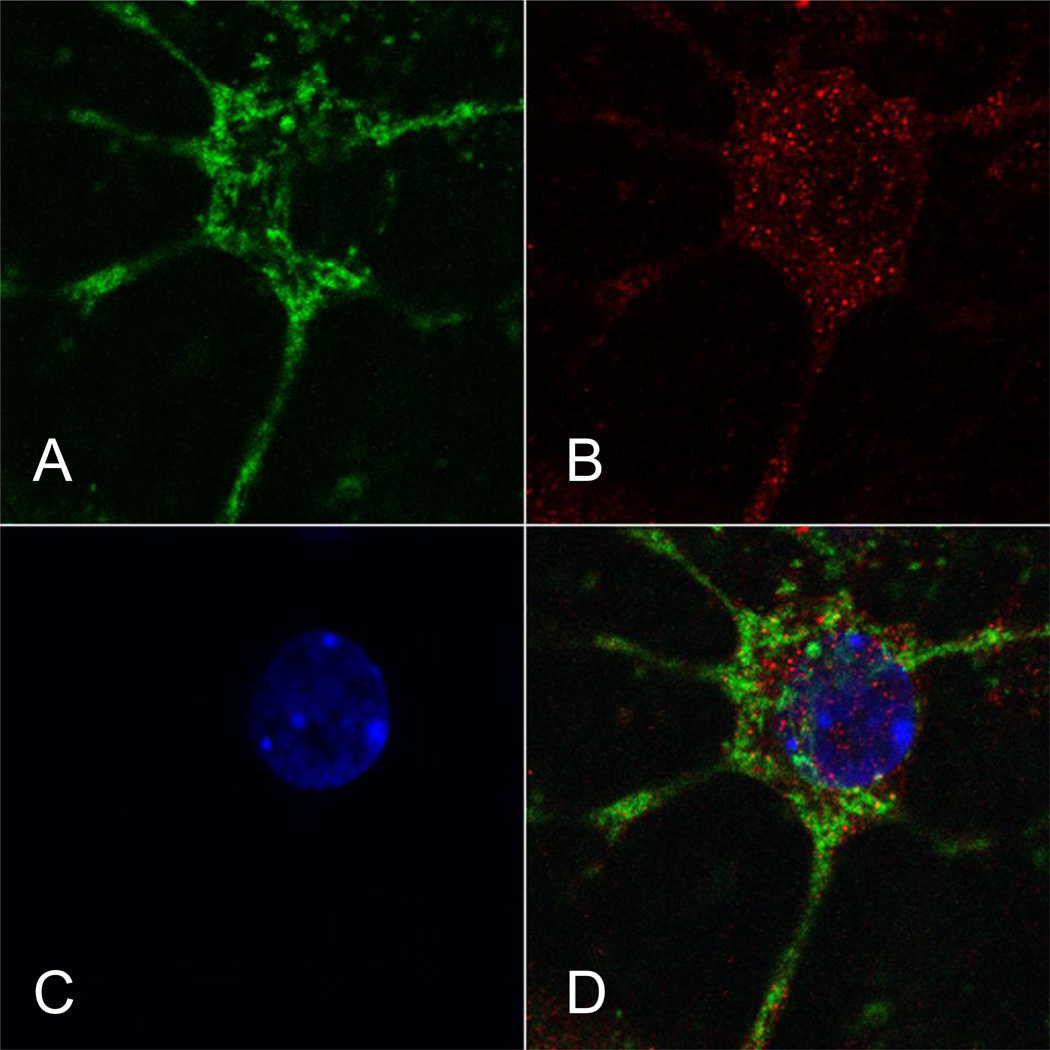

At the single cell level, the intraneuronal distribution of TET2 immunoreactivity was investigated in CGN cultures. Confocal microscopy of TET2 immunostaining showed a granular pattern and was found in the nucleus, the perinuclear area, and in the neurites. In several cases, TET2 immunofluorescence colocalized with the mitochondrial marker MTCO1 (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Confocal microscopy of ten-eleven-translocation (TET)2 immunostaining in cerebellar granule neurons (CGNs) in vitro. Neurons in culture were stained with a mitochondrial marker MTCO1 (A; green fluorescence), an anti-TET2 antibody (B; red fluorescence), and a nuclear marker DAPI (C; blue fluorescence). Images (a single optical section) were captured with a 100× objective lens. (D) Merged image. TET2 immunostaining appears granular. Most TET2 immunofluorescence is localized in the perinuclear area and in neuritis. TET2 signal is found in the nucleus and occasionally colocalized with a mitochondrial marker as indicated by yellow fluorescence.

3.6. Effect of aging on 5hmC and 5mC content in DNA extracted from Purkinje cells

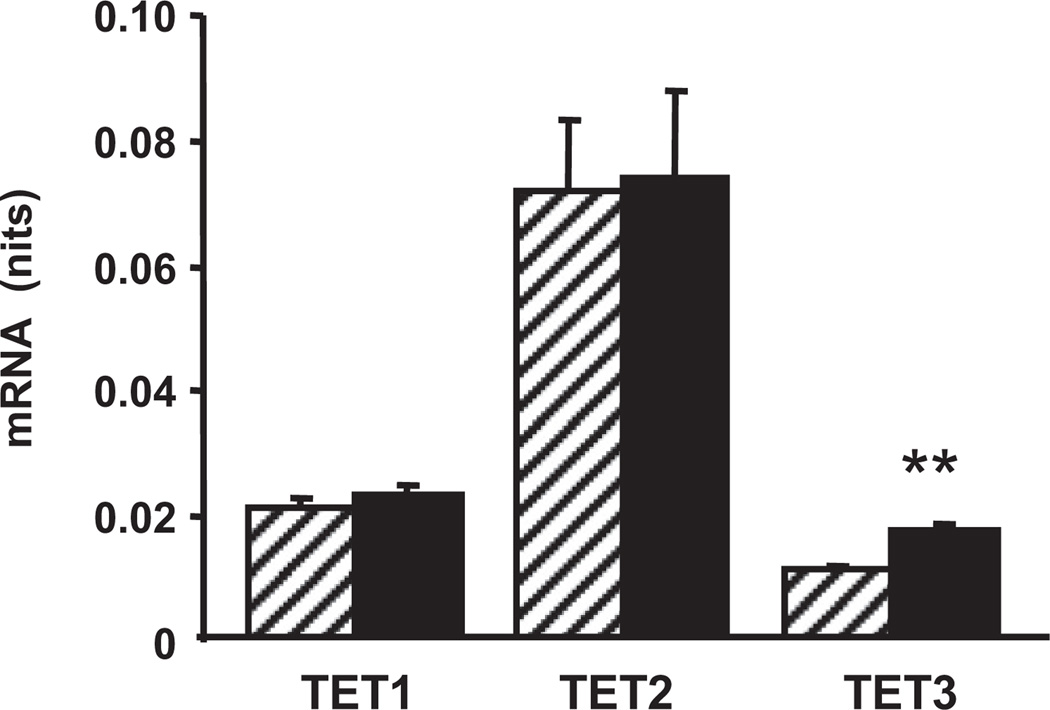

Our above-reported analyses of ncDNA and mtDNA obtained from cerebellar tissue comprising all types of cerebellar cells failed to detect significant effects of aging. Previous work has suggested that in the cerebellum, the primary site of 5hmC is in the Purkinje cells (Tahiliani et al., 2009). We confirmed both the Purkinje cell and the CGN localization of 5hmC (Supplementary Fig. 2). Hence, we used a laser capture microdissection procedure to collect samples from the Purkinje cell layer. Using the above-described restriction enzyme-based measurement of 5hmC content in selected sequences of mtDNA, we found elevated values of 5hmC in samples from old versus adult mice (Table 2). Furthermore, we measured the content of TET mRNAs in Purkinje cell samples and found aging-associated increase of TET3 mRNA (Fig. 8). The 5hmC content (but not the 5mC content) of Purkinje cell ncDNA also was significantly increased in the samples from old versus adult mice (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Table 2.

mtDNA 5hmC content in the Purkinje cell layer assessed with a restriction digest assay using mtDNA-targeted PCR primers

| mtDNA target | 4-Month-old | 24-Month-old |

|---|---|---|

| MnlI digest | ||

| ND2 | 0.26 ± 0.010 | 0.33 ± 0.010** |

| COX3 | 0.07 ± 0.007 | 0.16 ± 0.020** |

| tRNAs A, N, C, Y | 0.25 ± 0.020 | 0.52 ± 0.100* |

| AluI digest | ||

| ND4 | 0.14 ± 0.020 | 0.30 ± 0.030** |

| COX3 | 0.14 ± 0.010 | 0.33 ± 0.050** |

| tRNAs A, N, C, Y | 0.30 ± 0.050 | 0.74 ± 0.180* |

| HaeIII digest | ||

| ND2 | 0.36 ± 0.020 | 0.45 ± 0.010** |

| ND5 | 0.19 ± 0.020 | 0.29 ± 0.040* |

DNA was extracted from laser capture dissected samples, digested with the indicated restriction enzymes, and assayed with mtDNA-targeted polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primers as described in the text. Results are expressed in units (mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM]; n = 5).

Key: 5hmC, 5-hydroxymethylcytosine; mtDNA, mitochondrial DNA; tRNA,.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

Fig. 8.

Effect of aging on ten-eleven-translocation (TET)1–TET3 mRNA content in the Purkinje cell layer. Laser capture microdissection was used to obtain the Purkinje cell layer from cerebellar slices of 4-month-old (striped bars) and 24-month-old (filled bars) mice. mRNA content was measured with a quantitative real time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) assay. Results are expressed in units (mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM]; ** p < 0.01; n = 5).

4. Discussion

Collectively, our results demonstrated the presence of mitochondrial epigenetic mechanisms, particularly the hydroxymethylation pathway, in the mammalian central nervous system. Furthermore, our data revealed the susceptibility of mitochondrial epigenetics to dynamic modifications, as exemplified by aging-associated alterations.

Prior to the discovery of the functional role of TET enzymes in the formation of 5hmC (Dahl et al., 2011; Iyer et al., 2009; Tahiliani et al., 2009), it was believed that oxidative damage in nuclear and mitochondrial DNA accounted for the majority of oxidized bases, such as 5-hydroxycytosine (5hmC was not measured in these studies) (Wang et al., 2005, 2006). Although 5hmC can be produced by an action of free radicals on 5mC in artificial conditions (Castro et al., 1996), this mechanism has not been demonstrated in physiological conditions. Hence, the origin of 5hmC in genomic DNA had been linked to the enzymatic activity of TET proteins. In contrast to mtDNMT1, which contains a mitochondrial targeting sequence (Shock et al., 2011), no such sequence has been identified for TET proteins yet and further research is needed to elucidate whether TETs can utilize any of the known mechanisms for translocation of proteins across mitochondrial membranes (Marom et al., 2011). Using an antibody-based Western blotting assay and confocal microscopy, we found evidence for the presence of TET1 and TET2 in mouse neuronal mitochondria. Interestingly, we observed that the increased expression of TET2 and TET3 in the cerebellum and TET3 in the Purkinje cell layer of old mice was associated with increased 5hmC content of both ncDNA and mtDNA extracted from Purkinje cells of these mice. No aging-associated changes in TET mRNAs were found in the frontal cortex, a region in which only mtDNA 5hmC content was affected, i.e., decreased in old mice. Although our data indicate a possibility of a functional TET pathway in mitochondria, additional studies are needed to directly confirm a role for TET enzymes in the 5hmC modifications of mtDNA.

In addition, we found that global ncDNA cytosine 5-hydroxymethylation in the frontal cortex and the cerebellum did not differ between 24-month-old and 4-month-old mice. Similar to our findings is a report of no difference in cerebellar ncDNA 5hmC content between 10-month-old and 2.5-month-old mice (Song et al., 2011). On the other hand, previous work found a significant increase in global genomic 5hmC content in the hippocampus and/or the cerebellum of adult mice versus immature mouse pups (Song et al., 2011; Szulwach et al., 2011) and higher 5hmC values in ncDNA extracted from the cerebellar tissue of 12-month-old mice compared with 1.5-month-old mice (no difference was found in the hippocampus) (Szulwach et al., 2011).

In our experimental conditions, aging was associated with the increased expression of randomly selected mtDNA-encoded genes (ND2, ND4, ND4L, ND5, and ND6) in the cortex, i.e., a brain region with the aging-associated decreased content of mtDNA 5hmC, while no aging-associated mRNA changes were observed in the cerebellum, i.e., a brain region in which aging did not affect mtDNA 5hmC. Previously, it was reported that the expression of these selected genes was higher in the cortex of 12- and 18-month-old mice compared with 2-month-old mice (Manczak et al., 2005). mtDNA transcription, which produces polycistronic transcripts that are later processed into mature mRNAs, transfer RNAs (tRNAs) and ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs), is primarily regulated at a noncoding region known as the D-loop region (Rebelo et al., 2011). We found aging-associated changes in 5hmC both in this region and in the regions within the gene bodies of the studied mtDNA-encoded genes. The exact nature of the association between 5hmC levels and gene expression is currently poorly understood. Hence, we cannot conclude that decreased 5hmC levels in mtDNA are responsible for the increased expression of corresponding mtDNA-encoded genes. Nevertheless, others have observed that in ncDNA, 5hmC density is much higher at lowly expressed gene promoters and 5hmC levels are very low both at the promoter and the body of a set of genes with constantly high expression levels (Xu et al., 2011).

In this work, we demonstrated the presence of mtDNMT1 transcripts in various mouse brain regions and found that both mtDNMT1 and total DNMT1 mRNA expression in the central nervous system are altered during aging. Previously, mtDNMT1 transcription was characterized only in nonneuronal cell lines (Shock et al., 2011). In these in vitro studies, mtDNMT1 has been linked to the methylation of mtDNA. We confirmed the presence of 5mC not only in genomic DNA but also in mtDNA extracted from various mouse brain regions. Nevertheless, using an assay of global DNA methylation we did not observe significant differences in the 5mC content between DNA samples (both genomic and mtDNA) from 24- and 4-month-old mice. Although it has been proposed that aging leads to global DNA demethylation (Pogribny and Vanyushin, 2010), which would be consistent with our findings of decreased DNMT1 expression in the frontal cortex of old mice (this enzyme is no longer considered only a maintenance DNA methyltransferase; for review see Svedruić, 2011), recent work indicates that brain aging-associated 5mC changes in ncDNA occur in distinct regions of the genome (Chouliaras et al., 2011; Dzitoyeva et al., 2009; Hernandez et al., 2011; Siegmund et al., 2007; Takasugi, 2011). In an in vitro neuronal aging model, aging was associated with the decreased expression of DNMT1, an increased expression of DNMT3a, and the increased methylation of the studied gene sequences (Imbesi et al., 2009). Mouse mitochondrial DNA (NC_005089; the National Center for Biotechnology Information database) contains only 287 CpG dinucleotides. It is likely that sequence-specific (e.g., in CpG dinucleotides) and possibly bidirectional (Siegmund et al., 2007) alterations of mtDNA methylation occur during aging and that they are not found by the assays of global DNA methylation used in our present study. Future research is needed to explore the possibility that DNMT1 mutations, which have been linked with neurodegenerative disorders (Klein et al., 2011), may lead to aging-associated neuropathologies by impacting the methylation of both ncDNA and mtDNA.

Our immunofluorescence data from brain slices suggest a uniform distribution of a general (i.e., not separating nuclear from mitochondrial) 5hmC labeling in the mouse frontal cortex (data not shown) compared with a heterogeneous 5hmC distribution in the cerebellum, in which 5hmC was found predominantly in Purkinje cells and CGNs (Supplementary Fig. 2). This regional difference could explain why in DNA extracted from a total tissue (as opposed to DNA from a cell type-specific samples), aging-associated 5hmC alterations were found only in the frontal cortex, i.e., a brain region with a uniform 5hmC distribution. In the cerebellum, the same 5hmC assays (global and sequence-specific) that did not detect aging-associated differences in total tissue samples revealed these differences in a 5hmC-rich Purkinje cell layer.

In conclusion, using a combination of assays for assessing mitochondrial 5hmC, we demonstrated the presence of this epigenetic marker in the mtDNA of the central nervous system (including in neurons) and its susceptibility to physiological changes, e.g., during aging. In addition, we provided evidence for the effects of aging on the expression of brain TETs and provided evidence for the association of TET proteins with neuronal mitochondria, suggesting a putative involvement of TETs in the formation of 5hmC in mtDNA. Furthermore, for the first time we demonstrated the presence of mtDNMT1 transcript in the brain and found that its expression is affected by aging. Nevertheless, the study has several limitations that have been taken into account in data interpretation. For example, the number of animals per group is 5, which may be taken as indication of a lack of sufficient power to demonstrate significant changes in 5mC levels during aging. For example, Supplementary Fig. 3 suggests a nonsignificant 5mC increase with age. However, in our preliminary studies with 2- and 22-month-old mice we obtained similar results as shown in this figure, i.e., aging-associated 5hmC increase and no significant change in 5mC levels (data not shown). Moreover, we further analyzed the data from Supplementary Fig. 3. Thus, for each sample we calculated the 5hmC values as a percentage of the corresponding 5mC values. Even with this consideration, the 5hmC values were significantly higher in the samples from old versus adult mice (old = 6.4 ± 0.36; adult = 3.3 ± 0.56; p < 0.01). Another limitation of our study stems from technological limitations of the current assays for accurate and selective 5mC measurements in selected DNA sequences (Jin et al., 2010). Hence, the focus of our work was on the 5hmC alterations. With this caveat in mind, our study provides new perspectives on the role of epigenetic mechanisms in the central nervous system by extending their reach beyond the genomic DNA, i.e., into the field of mitochondrial epigenetics.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R01AG015347 from the National Institute on Aging (NIA) to H.M. NIH and NIA had no role in the preparation, review, or approval of this manuscript. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessary represent the official views of the NIA.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

The authors disclose no conflict of interest.

Animal procedures were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes on Health guidelines for the use of experimental animals and were approved by the University of Illinois Animal Care and Use Committee.

Appendix. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.02.006.

References

- Cardon LR, Burge C, Clayton DA, Karlin S. Pervasive CpG suppression in animal mitochondrial genomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1994;91:3799–3803. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.3799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro GD, Díaz Gómez MI, Castro JA. 5-Methylcytosine attack by hydroxyl free radicals and during carbon tetrachloride promoted liver microsomal lipid peroxidation: structure of reaction products. Chem. Biol. Interact. 1996;99:289–299. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(95)03680-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Dzitoyeva S, Manev H. 5-Lipoxygenase in mouse cerebellar Purkinje cells. Neuroscience. 2010;171:383–389. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng A, Hou Y, Mattson MP. Mitochondria and neuroplasticity. ASN. New Eur. 2010;2:e00045. doi: 10.1042/AN20100019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chouliaras L, van den Hove DL, Kenis G, Keitel S, Hof PR, van Os J, Steinbusch HW, Schmitz C, Rutten BP. Prevention of agerelated changes in hippocampal levels of 5-methylcytidine by caloric restriction. Neurobiol. Aging. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.06.003. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dahl C, Grønbæk K, Guldberg P. Advances in DNA methylation, 5-hydroxymethylcytosine revisited. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2011;412:831–836. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis T, Vaisvila R. High sensitivity 5-hydroxymethylcytosine detection in Balb/C brain tissue. J. Vis. Exp. 2011;48:pii:2661. doi: 10.3791/2661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day JJ, Sweatt JD. Cognitive neuroepigenetics: a role for epigenetic mechanisms in learning and memory. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2011;96:2–12. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzitoyeva S, Imbesi M, Ng LW, Manev H. 5-Lipoxygenase DNA methylation and mRNA content in the brain and heart of young and old mice. Neural Plast. 2009;2009:209596. doi: 10.1155/2009/209596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkenberg M, Larsson NG, Gustafsson CM. DNA replication and transcription in mammalian mitochondria. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2007;76:679–699. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.060305.152028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favaron M, Manev H, Alho H, Bertolino M, Ferret B, Guidotti A, Costa E. Gangliosides prevent glutamate and kainate neurotoxicity in primary neuronal cultures of neonatal rat cerebellum and cortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1988;85:7351–7355. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.19.7351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greaves LC, Reeve AK, Taylor RW, Turnbull DM. Mitochondrial DNA and disease. J. Pathol. 2012;226:274–286. doi: 10.1002/path.3028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez DG, Nalls MA, Gibbs JR, Arepalli S, van der Brug M, Chong S, Moore M, Longo DL, Cookson MR, Traynor BJ, Singleton AB. Distinct DNA methylation changes highly correlated with chronological age in the human brain. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011;20:1164–1172. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imbesi M, Dzitoyeva S, Ng LW, Manev H. 5-Lipoxygenase and epigenetic DNA methylation in aging cultures of cerebellar granule cells. Neuroscience. 2009;164:1531–1537. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.09.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer LM, Tahiliani M, Rao A, Aravind L. Prediction of novel families of enzymes involved in oxidative and other complex modifications of bases in nucleic acids. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:1698–1710. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.11.8580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin SG, Kadam S, Pfeifer GP. Examination of the specificity of DNA methylation profiling techniques towards 5-methylcytosine and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e125. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein CJ, Botuyan MV, Wu Y, Ward CJ, Nicholson GA, Hammans S, Hojo K, Yamanishi H, Karpf AR, Wallace DC, Simon M, Lander C, Boardman LA, Cunningham JM, Smith GE, Litchy WJ, Boes B, Atkinson EJ, Middha S, B Dyck PJ, Parisi JE, Mer G, Smith DI, Dyck PJ. Mutations in DNMT1 cause hereditary sensory neuropathy with dementia and hearing loss. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:595–600. doi: 10.1038/ng.830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriaucionis S, Heintz N. The nuclear DNA base 5-hydroxymethylcytosine is present in Purkinje neurons and the brain. Science. 2009;324:929–930. doi: 10.1126/science.1169786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, van Groen T, Kadish I, Tollefsbol TO. DNA methylation impacts on learning and memory in aging. Neurobiol. Aging. 2009;30:549–560. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manczak M, Jung Y, Park BS, Partovi D, Reddy PH. Time-course of mitochondrial gene expressions in mice brains: implications for mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative damage, and cytochrome c in aging. J. Neurochem. 2005;92:494–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manev H, Dzitoyeva S, Chen H. Mitochondrial DNA: a blind spot in neuroepigenetics. Biomol. Concepts. 2012 doi: 10.1515/bmc-2011-0058. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marom M, Azem A, Mokranjac D. Understanding the molecular mechanisms of protein translocation across the mitochondrial inner membrane: still a long way to go. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011;1808:990–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastroeni D, Grover A, Delvaux E, Whiteside C, Coleman PD, Rogers J. Epigenetic mechanisms in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 2011;32:1161–1180. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Münzel M, Globisch D, Carell T. 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine, the sixth base of the genome. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2011;50:6460–6468. doi: 10.1002/anie.201101547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Franklin KBJ. The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. London: Academic Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Penner MR, Roth TL, Barnes CA, Sweatt JD. An epigenetic hypothesis of aging-related cognitive dysfunction. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2010;2:9. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2010.00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogribny IP, Vanyushin BF. Age-related genomic hypomethylation. In: Tollefsbol TO, editor. Epigenetics of Aging. New York: Springer; 2010. pp. 11–27. [Google Scholar]

- Rebelo AP, Dillon LM, Moraes CT. Mitochondrial DNA transcription regulation and nucleoid organization. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2011;34:941–951. doi: 10.1007/s10545-011-9330-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riccio A. Dynamic epigenetic regulation in neurons: enzymes, stimuli and signaling pathways. Nat. Neurosci. 2010;13:1330–1337. doi: 10.1038/nn.2671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shock LS, Thakkar PV, Peterson EJ, Moran RG, Taylor SM. DNA methyltransferase 1, cytosine methylation, and cytosine hydroxymethylation in mammalian mitochondria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011;108:3630–3635. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012311108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegmund KD, Connor CM, Campan M, Long TI, Weisenberger DJ, Biniszkiewicz D, Jaenisch R, Laird PW, Akbarian S. DNA methylation in the human cerebral cortex is dynamically regulated throughout the life span and involves differentiated neurons. PLoS One. 2007;2:e895. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song CX, Szulwach KE, Fu Y, Dai Q, Yi C, Li X, Li Y, Chen CH, Zhang W, Jian X, Wang J, Zhang L, Looney TJ, Zhang B, Godley LA, Hicks LM, Lahn BT, Jin P, He C. Selective chemical labeling reveals the genome-wide distribution of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29:68–72. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SvedružiSvedru ŽM. Dnmt1 structure and function. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2011;101:221–254. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-387685-0.00006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swerdlow RH. Brain aging, Alzheimer’s disease, and mitochondria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011;1812:1630–1639. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szulwach KE, Li X, Li Y, Song CX, Wu H, Dai Q, Irier H, Upadhyay AK, Gearing M, Levey AI, Vasanthakumar A, Godley LA, Chang Q, Cheng X, He C, Jin P. 5-hmC-mediated epigenetic dynamics during postnatal neurodevelopment and aging. Nat. Neurosci. 2011;14:1607–1616. doi: 10.1038/nn.2959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahiliani M, Koh KP, Shen Y, Pastor WA, Bandukwala H, Brudno Y, Agarwal S, Iyer LM, Liu DR, Aravind L, Rao A. Conversion of 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine in mammalian DNA by MLL partner TET1. Science. 2009;324:930–935. doi: 10.1126/science.1170116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takasugi M. Progressive age-dependent DNA methylation changes start before adulthood in mouse tissues. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2011;132:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tranah GJ. Mitochondrial-nuclear epistasis: implications for human aging and longevity. Ageing Res. Rev. 2011;10:238–252. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turturro A, Witt WW, Lewis S, Hass BS, Lipman RD, Hart RW. Growth curves and survival characteristics of the animals used in the Biomarkers of Aging Program. J. Gerontol. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 1999;54:B492–B501. doi: 10.1093/gerona/54.11.b492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanyushin BF, Kirnos MD. Structure of animal mitochondrial DNA (base composition, pyrimidine clusters, character of methylation) Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1977;475:323–336. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(77)90023-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace DC, Fan W. Energetics, epigenetics, mitochondrial genetics. Mitochondrion. 2010;10:12–31. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Markesbery WR, Lovell MA. Increased oxidative damage in nuclear and mitochondrial DNA in mild cognitive impairment. J. Neurochem. 2006;96:825–832. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Xiong S, Xie C, Markesbery WR, Lovell MA. Increased oxidative damage in nuclear and mitochondrial DNA in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurochem. 2005;93:953–962. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Wu F, Tan L, Kong L, Xiong L, Deng J, Barbera AJ, Zheng L, Zhang H, Huang S, Min J, Nicholson T, Chen T, Xu G, Shi Y, Zhang K, Shi YG. Genome-wide regulation of 5hmC, 5mC, and gene expression by Tet1 hydroxylase in mouse embryonic stem cells. Mol. Cell. 2011;42:451–464. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.