Abstract

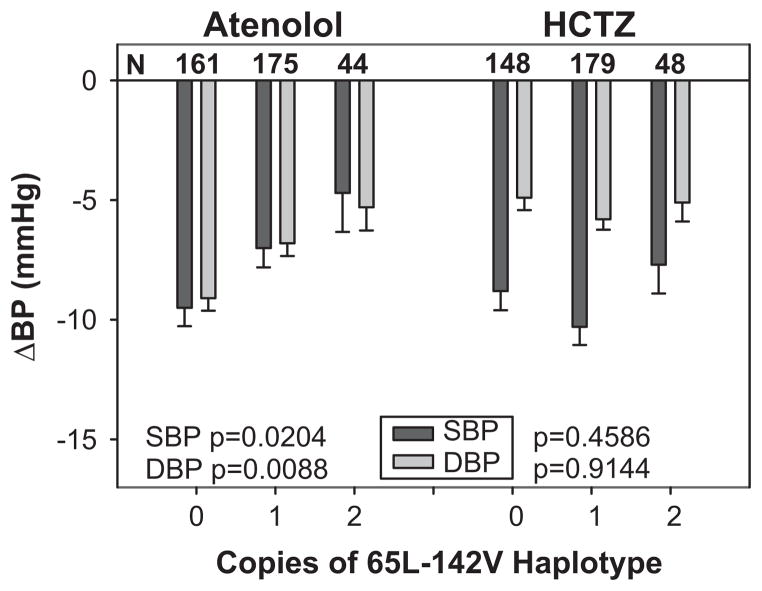

G protein-coupled receptor kinases (GRKs) are important regulatory proteins for many G protein-coupled receptors, but little is known about GRK4 pharmacogenetics. We hypothesized three nonsynonymous GRK4 SNPs, R65L (rs2960306), A142V (rs1024323) and A486V (rs1801058) would be associated with blood pressure response to atenolol, but not hydrochlorothiazide, and would be associated with long term cardiovascular outcomes (all cause, death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke) in participants treated with an atenolol-based versus verapamil-SR-based antihypertensive strategy. GRK4 SNPs were genotyped in 768 hypertensive participants from the Pharmacogenomic Evaluation of Antihypertensive Responses (PEAR) trial. In Caucasians and African Americans, increasing copies of the variant 65L-142V haplotype were associated with significantly reduced atenolol-induced diastolic blood pressure lowering (−9.1 ± 6.8 vs −6.8 ± 7.1 vs −5.3 ± 6.4 mmHg in participants with 0, 1 and 2 copies of 65L-142V respectively; p=0.0088). 1460 participants with hypertension and coronary artery disease from the INternational VErapamil SR / Trandolapril STudy (INVEST) were genotyped and variant alleles of all three GRK4 SNPs were associated with increased risk for adverse cardiovascular outcomes in an additive fashion, with 486V homozygotes reaching statistical significance (Odds ratio 2.29 [1.48–3.55], p=0.0002). These effects on adverse cardiovascular outcomes were independent of antihypertensive treatment. These results suggest the presence of GRK4 variant alleles may be important determinants of blood pressure response to atenolol and risk for adverse cardiovascular events. The associations with GRK4 variant alleles were stronger in patients who were also ADRB1 389R-homozygotes, suggesting a potential interaction between these two genes.

Keywords: hypertension, GRK4, atenolol, beta-blocker, outcomes, ADRB1, pharmacogenetics

Introduction

β-adrenergic receptor blockers (β-blockers) are commonly used in treatment of hypertension, however their efficacy varies widely. Monotherapy fails to achieve adequate blood pressure (BP) reduction in 30% to 60% of participants1. Genetic differences in β-adrenergic receptors (β-AR) and associated regulatory proteins, such as G protein-coupled receptor kinase (GRK) family members, may account for some of this variability. GRKs are a family of serine/threonine kinases that phosphorylate activated G protein-coupled receptors (GPCR) leading to subsequent receptor desensitization, deactivation and endocytosis2. GRK family members have been implicated in BP regulation and hypertension3–5 and have been associated with cardiovascular (CV) diseases, including heart failure and cardiac hypertrophy2. An important but understudied GRK family member, GRK4, is highly expressed in kidney, brain, testes and skeletal muscle6, and modestly expressed in the heart7. GRK4 plays a role in BP homeostasis through phosphorylation of GPCRs important to BP regulation including dopamine receptors, and potentially β1-ARs, the key protein target of β-blockers.

Three nonsynonymous SNPs in GRK4 are proposed to have important physiologic and potential pharmacogenomic effects. R65L (rs2960306) and A142V (rs1024323) consist of G to T and C to T substitutions respectively, and are located in the GPCR interacting region of GRK4. The A486V (rs1801058) SNP is a G to T substitution located in the membrane targeting region8. All three SNPs are proposed to represent gain of function polymorphisms enhancing the ability of GRK4 to bind to, phosphorylate and desensitize GPCRs, with most data currently focusing on dopamine receptors4, 8–10.

To date, only one pharmacogenetic study has been carried out examining the effect of GRK4 SNPs on BP response to the β-blocker metoprolol succinate in African Americans as part of the African American Study of Kidney Disease (AASK) trial11. This study found that in participants taking metoprolol, those with both the 65L and 142A alleles took longer to achieve BP control than participants without this genotype combination. However, these findings were restricted to African American males and had limited power, further underscoring the need for additional investigation.

The β1-adrenergic receptor (B1AR) is a seven transmembrane domain GPCR that is widely expressed in heart and kidneys and plays an important role in regulating BP. The R389G SNP (rs1801253) in the β1-AR receptor gene, ADRB1, has been shown to affect patient response to β-blockers, with several studies demonstrating that participants who are 389R homozygotes exhibit markedly greater responses to β-blockers than 389G carriers12–16. While there is no direct evidence that GRK4 phosphorylates β1-ARs, there is ample evidence that GRK5 phosphorylates and attenuates function of both receptors. Specifically, we have previously shown that genetic variants of GRK5 can influence β1-AR and β2-AR function in vitro17, 18 or in vivo17. In addition, we have shown that the R389 form of β1-AR achieves a more favorable conformation for GRK-mediated desensitization compared to G38919.

We tested the hypothesis that specific GRK4 polymorphisms affect the magnitude of BP response to the β-blocker atenolol and that these polymorphisms affect risk for experiencing adverse CV outcomes in participants treated with a β-blocker versus a calcium channel blocker (CCB) strategy. If these GRK4 polymorphisms act in a gain of function fashion, then it is possible that they reduce efficacy of β-blocker therapy, since they might behave like an endogenous β-blocker, a term that has been attributed to a gain of function SNP in GRK517. Additionally, we sought to examine whether an interaction between GRK4 and ADRB1 may be present.

Methods

Pharmacogenomic Evaluation of Antihypertensive Response (PEAR) Trial

PEAR details have been previously described (www.clinicaltrials.gov, NCT00246519)20. Briefly, participants with mild to moderate hypertension (home DBP >85 mm Hg and office DBP >90 mm Hg) aged 17–65 were enrolled at University of Florida (Gainesville, FL), Emory University (Atlanta, GA) or Mayo Clinic (Rochester, MN). Following enrollment, current antihypertensive therapy was discontinued. After a washout period of four to six weeks (18 days minimum), hypertension was confirmed, and participants were randomized to receive monotherapy with either atenolol or hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ). The adequacy of this washout period was documented by verifying that post-washout BP levels in previously treated participants were “nearly identical” to those who were untreated (145.8/93.7 mmHg vs 146.1/94.0 mmHg, respectively). Participants were randomized to atenolol 50 mg/day or HCTZ 12.5 mg/day, and then titrated to 100 mg/day or 25 mg/day, respectively, if BP remained above 120/70 mmHg after three weeks. After nine weeks of treatment, if BP remained above 120/70 mmHg the other drug was added, with a similar dose titration step, and participants were followed for nine additional weeks. Home BP measurements obtained at baseline and after nine weeks of monotherapy were used in this study. PEAR was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) at each study center and all participants provided informed written consent to participate and supply genetic material. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

INternational VErapamil SR / Trandolapril Study (INVEST)

INVEST (NCT00133692)21 and INVEST-GENES22 designs and patient demographics have been previously published. Briefly, participants over age 50 with documented coronary artery disease (CAD) and hypertension were enrolled. Genetic samples were collected from participants enrolled at 184 sites in the United States and Puerto Rico as a part of the INVEST-GENES substudy. All participants provided separate written informed consent to participate in INVEST and INVEST-GENES, and the trial was approved by appropriate IRBs. Participants were randomized to either CCB (verapamil-SR) or β-blocker (atenolol) based treatment strategies. Participants had a clinical assessment performed at baseline, six, 12, 18, and 24 weeks, then every six months until two years after the last patient was enrolled. Participants were randomized to receive either atenolol or verapamil-SR, with addition of HCTZ and/or trandolapril allowed in either arm, for BP control and organ protection. Participants were followed for a mean of 2.8 ± 0.7 years for development of the primary outcome, which was first occurrence of death (all causes), nonfatal myocardial infarction (MI) or nonfatal stroke. Genetic samples were available on 292 participants who experienced the primary outcome during follow-up (cases), who were frequency matched in a ratio of approximately 1:4 for age (by decade), sex and race/ethnicity with 1168 participants who did not experience an outcome event (controls). Genetic samples were available for all individuals in the case-control cohort.

Genotyping

Genotype information for the GRK4 SNPs rs1024323 (Ala142Val) and rs1801058 (Ala486Val) and the ADRB1 SNP rs1801253 (Arg389Gly) were acquired using the Human CVD genotyping bead chip (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Genotyping of rs2960306 (Arg65Leu) in GRK4 was performed using the Taqman system and probes (ID C_11764476_20), both purchased from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA). Five μL reactions were prepared in 384 well plates. Assays were performed and analyzed according to manufacturer’s instructions. The R65L Taqman assay was conducted with approximately 17% replication for quality control which resulted in a concordance rate of 98%. Standard quality control procedures were applied to the HumanCVD chip. Patients were excluded if sample genotype call rates were below 95% and SNPs were excluded if genotype call rates were below 90%. 81 blind duplicates were included in genotyping and had a concordance rate of 99.992%. Principal component analysis was performed in all subjects in each ethnic group using an LD pruned dataset using the EIGENSTRAT method2 implemented through JMP Genomics version 5.0 (SAS Institute, Cary NC). The best separation of ancestry clusters was provided by principal components 1–2 for PEAR and 1–3 for INVEST. These were used as covariates for subsequent analysis.

Statistics and Analysis

All statistical analyses were carried out using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute). Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium was confirmed separately for each race group/ethnicity using a χ2 test at α=0.05 with one degree of freedom. Linkage disequilibrium was determined using Haploview 4.2 (Broad Institute, Cambridge MA). Haplotypes were determined using PHASE 2.1 (University of Chicago, Chicago IL).

To account for multiple comparisons, a Bonferroni corrected p-value of 0.017 (p=0.05/3) was considered significant since three GRK4 polymorphisms were included in the analysis. Because a goal of this study was to generate novel hypothesis regarding influence of GRK4 polymorphisms on β-blocker therapy, p < 0.05 are also reported in figures and tables.

BP Analysis in PEAR

BP response in PEAR was evaluated separately for each race group and for both races combined with trend tests using linear regression adjusted for age, baseline BP, gender, and principal components where appropriate. The SNPs examined in this study are functional SNPs, therefore when associations by race were consistent, data were pooled and controlled for race. For PEAR BP analysis, we have 80% power with an alpha of 0.05 to detect the following differences in systolic and diastolic BP response in the combined analysis (3.9/2.2 mmHg), in Caucasians (3.9/2.3 mmHg), and in African Americans (4.2/3.6 mmHg).

CV Outcomes Analysis in INVEST-GENES

Data from INVEST-GENES suggests that in participants who are 389R carriers, atenolol, as compared to verapamil, provide a protective effect against adverse cardiovascular outcomes23. To test for an interaction between GRK4 and the functional ADRB1 R389G SNP, INVEST-GENES case control participants were divided into ADRB1 389G-carriers and 389R-homozygotes 12–16. The effects of GRK4 SNPs and haplotypes on BP reduction and CV outcomes were examined within each ADRB1 genotype group.

The INVEST-GENEs nested case-control cohort (1:4; n=1460) was analyzed for risk estimates of the primary outcome. These models controlled for age, gender, prior MI, prior heart failure (class I-III), history of diabetes and principal components. To determine risk for experiencing the primary outcome, logistic regression models were used. To analyze risk per variant allele, logistic regression models were used with genotype coded 0, 1, 2. The case-control cohort was stratified by treatment arm (atenolol or verapamil) to determine whether a treatment effect was present. At 292 cases and 1168 controls, we have greater than 80% at alpha of 0.05 power to detect odds ratio greater than 1.31.

Results

Study Samples and Baseline Characteristics

Baseline characteristics for PEAR participants are summarized in Table 1. PCA determined races were equally distributed between the two treatment arms, however the atenolol arm contained more women than the HCTZ arm. Baseline characteristics for INVEST case-control participants are summarized in Table 2. There were no differences in age, race or gender between cases and controls. Cases had lower BMI and higher rates of previous MI, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, stroke / transient ischemic attack, diabetes and renal impairment. The PEAR sample predominantly contained Caucasians (57.2%) and African Americans (38.3%), while the INVEST sample consisted primarily of Caucasians (60.9%) and Hispanics (24.7%), with a small sample of African Americans (14.0%).

Table 1.

PEAR Baseline Characteristics

| Characteristic | All participants (n = 768) | Atenolol (n = 387) | HCTZ (n = 381) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 48.8 ± 9.2 | 48.7 ± 9.2 | 48.9 ± 9.3 |

| Women | 405 (52.7) | 217 (56.1) | 188 (49.3) |

| Caucasians | 439 (57.2) | 222 (57.4) | 217 (56.9) |

| African Americans | 294 (38.3) | 146 (37.7) | 148 (38.9) |

| White Hispanics | 12 (1.6) | 6 (1.6) | 6 (1.6) |

| Black Hispanics | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) |

| Asians | 8 (1.0) | 5 (1.3) | 3 (0.8) |

| Other / multiracial | 14 (1.8) | 7 (1.8) | 7 (1.8) |

| Duration of hypertension (years) | 6.6 ± 7.2 | 6.8 ± 7.1 | 6.4 ± 7.3 |

| Family history of hypertension | 586 (76.4) | 300 (77.5) | 286 (75.2) |

| Taking antihypertensive at study entry | 675 (87.9) | 340 (87.9) | 336 (88.2) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30.8 ± 5.5 | 30.8 ± 5.9 | 30.8 ± 5.1 |

| Smoker (ever) | 644 (83.5) | 328 (84.5) | 316 (82.5) |

| Home SBP (mmHg) | 145.7 ± 10.3 | 145.0 ± 9.9 | 146.6 ± 10.6 |

| Home DBP (mmHg) | 93.7 ± 5.9 | 93.3 ± 5.9 | 94.2 ± 6.0 |

| Home HR (beats/min) | 77.5 ± 9.5 | 77.8 ± 9.4 | 77.2 ± 9.5 |

Data presented ± standard deviation, or n (%)

Table 2.

INVEST Baseline Characteristics

| Characteristic | Cases (n = 292) | Controls (n = 1168) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 71.4 ± 9.8 | 70.3 ± 9.1 |

| Women | 143 (48.9) | 602 (51.5) |

| Caucasians | 178 (60.9) | 690 (59.1) |

| African Americans | 41 (14.0) | 155 (13.3) |

| Hispanics | 72 (24.7) | 318 (27.2) |

| Other / multiracial | 1 (0.3) | 5 (0.4) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.4 ± 4.7 | 28.9 ± 5.4 |

| Smoker (all time) | 153 (52.4) | 461 (39.5) |

| Past Medical History | ||

| Myocardial infarction | 107 (36.6) | 286 (24.5) |

| Stroke / TIA | 43 (14.7) | 80 (6.9) |

| Left ventricular hypertrophy | 51 (17.5) | 172 (14.7) |

| Heart failure (class I–III) | 30 (10.3) | 51 (4.4) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 50 (17.1) | 121 (10.4) |

| Diabetes | 107 (36.6) | 226 (19.4) |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 186 (63.7) | 708 (60.6) |

| Renal impairment | 17 (5.8) | 24 (2.1) |

Data presented ± standard deviation, or n (%)

Genotyping Results

Of 768 PEAR participants, GRK4 was successfully genotyped in 759 (98.8%) at R65L, 767 (99.9%) at A142V, 767 (99.9%) at A486V, and ADRB1 R389G was successfully genotyped in 767 (99.9%) participants. Of 1460 INVEST participants, GRK4 was successfully genotyped in 1408 (96.4%) at R65L, 1454 (99.6%) at A142V, 1454 (99.6%) at A486V, and ADRB1 R389G was successfully genotyped in 1451 (99.4%) participants. All polymorphisms were in Hardy- Weinberg equilibrium for each race group. Minor allele frequencies (MAF) are consistent with those previously reported (Table S1). MAFs for all SNPs in all races exceeded 0.38 except A486V in African Americans, which was 0.12 to 0.14. Due to similarities between GRK4 linkage disequilibrium (LD) patterns in both PEAR and INVEST samples, a pooled LD analysis was performed. Based on r2 values, there was low LD between GRK4 SNPs in African Americans. In both Caucasians and Hispanics, low to moderate LD was observed between GRK4 R65L and A142V. LD results (Fig. S1) were similar to those previously reported11, 24, 25.

Effect of GRK4 Polymorphisms on BP Response to Atenolol Monotherapy in PEAR

In Caucasians, variant alleles for all three SNPs showed or trended towards less BP lowering. Similar findings were observed in African Americans, except for 486V, which was less common in African Americans, and therefore underpowered. When African Americans and Caucasians were combined, variant alleles 65L and 142V were associated with less DBP lowering with atenolol, with similar trends present for SBP (Table S2).

Since both 65L and 142V variant alleles exhibited less BP lowering, we constructed haplotypes, and as expected, increasing copies of the variant 65L-142V haplotype were associated with significantly less BP lowering (Fig. 1, Table S3). In contrast, increasing copies of the 65R-142A haplotype were associated with increased SBP and DBP responses to atenolol. GRK4 haplotype prevalence differed by race, 31.2% for 65R-142A, 18.5% for 65R-142V, 6.4% for 65L-142A and 43.9% for 65L-142V in African Americans, and 60.5% for 65R-142A, 5.0% for 65R-142V, 3.4% for 65L-142A and 31.1% for 65L-142V in Caucasians. No atenolol treated participants in either race had two copies of the 65L-142A haplotype, and no atenolol treated Caucasian participants had two copies of the 65R-142V haplotype.

Figure 1. Effects of GRK4 65L-142V haplotype on BP response in PEAR.

Change in SBP and DBP with increasing copies of the 65L-142V haplotype are shown in participants treated with either atenolol or HCTZ monotherapy.

Effect of GRK4 Polymorphisms on CV Outcomes in INVEST

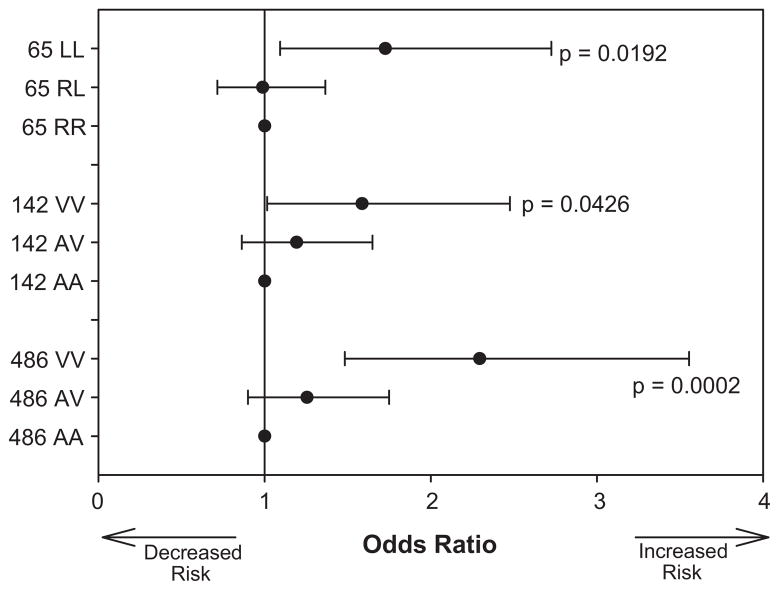

Analyses were first performed separately by PCA determined race. Due to similarities in direction of the point estimates, Caucasians and Hispanics were combined. Power was too low in African Americans to allow for sufficient analysis in this race group. All three GRK4 variants were associated with increased risk for the primary outcome (first occurrence of all cause death, nonfatal MI, or nonfatal stroke) in pooled Caucasians and Hispanics who were homozygous for 65L (Odds Ratio 1.73 95% confidence interval [1.09–2.73], p=0.0192), 142V (OR 1.59 [1.01–2.48], p=0.0426) and 486V (OR 2.29 [1.48–3.55], p=0.0002) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Effect of GRK4 polymorphisms on CV outcome in INVEST.

Risk of experiencing the primary outcome (first occurrence of death (all causes), non-fatal myocardial infarction or non-fatal stroke) is shown by genotype for each of the GRK4 SNPs.

When stratified by treatment group, point estimates of risk for the primary outcome per 65L or 142V variant alleles appeared similar in Caucasians and Hispanics in both verapamil and atenolol based treatment groups, suggesting only a main effect, and not a pharmacogenetic effect for these SNPs with the primary outcome. There was no difference in on treatment BP between GRK4 genotypes or haplotypes (not shown). When compared against the main effect analysis, risk for the primary outcome associated with the 486V variant declined and became nonsignificant in participants in the β-blocker (atenolol) based strategy (OR 1.32 [0.95–1.84]; p=0.0973) and increased for participants in the CCB (verapamil-SR) based strategy (OR 1.58 [1.18–2.12], p=0.0024) (Table S4).

Influence of ADRB1 R389G on Effects of GRK4 SNPs in PEAR and INVEST

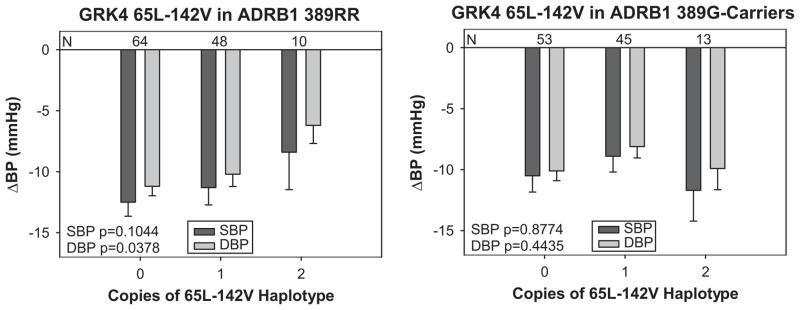

Potential effects of interactions between ADRB1 R389G and GRK4 variants on BP response and primary outcome were examined. In PEAR, the association between GRK4 65L or 142V with decreased response was only observed in Caucasian ADRB1 389R-homozygotes (Fig. 3). In African Americans, similar trends appeared in both ADRB1 389R-homozygotes and 389G-carriers, with increasing copies of GRK4 65L or 142V correlating with decreased BP response. It is important to note that the ADRB1 genotype association with β-blocker response is less well defined in African Americans.

Figure 3. Effects of GRK4 65L-142V haplotype and ADBR1 R389G status on BP response in PEAR.

Changes in SBP and DBP in response to atenolol monotherapy are show in participants who are ADRB1 389R-homozygotes or 389G-carriers with increasing copies of the 65L-142V haplotype.

Consistent with data for BP response, there was some evidence of a greater genetic effect of ADRB1 R389R on CV outcomes in INVEST. Specifically, presence of the GRK4 142V variant was associated with increased risk for the primary outcome in ADRB1 389R-homozygotes (OR 1.59 [1.17–2.17], p=0.0033), but not 389G-carriers (p=0.9628). Similarly, the GRK4 65L-142V haplotype was nominally significant for increased risk in ADRB1 389Rhomozygotes (OR 1.44 [1.04–1.98], p=0.0283), but not 389-G carriers (p=0.5731). The GRK4 486V variant was associated with risk (point estimates) in both ADRB1 genotype groups (Table 3). A gene*gene interaction between GRK4 and ADRB1 was not significant in either PEAR or INVEST.

Table 3.

Risk per variant allele of GRK4 of experiencing the primary outcome by ADRB1 R389G status in Caucasians and Hispanics in INVEST.

| ADRB1 389R-homozygotes

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| GRK4 Genotype | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | P value |

| 65L | 1.27 | 0.93–1.73 | 0.1410 |

| 142V | 1.59 | 1.17–2.17 | 0.0033* |

| 65L-142V haplotype | 1.44 | 1.04–1.98 | 0.0283* |

| 486V | 1.40 | 1.03–1.92 | 0.0326* |

|

| |||

|

ADRB1 389G-carriers

| |||

| 65L | 1.22 | 0.89–1.67 | 0.2216 |

| 142V | 1.01 | 0.74–1.38 | 0.9628 |

| 65L-142V haplotype | 1.09 | 0.79–1.51 | 0.5731 |

| 486V | 1.60 | 1.17–2.19 | 0.0033* |

Discussion

Our study extends the literature base surrounding the effect on disease risk and the pharmacogenomic effects of three nonsynonymous GRK4 polymorphisms (R65L, A142V, A486V). Findings herein suggest GRK4 65L and 142V variant alleles and the 65L-142V haplotype are associated with reduced response to β-blocker monotherapy and increased risk of experiencing an adverse long-term CV outcome. In the combined analysis, when corrected for multiple comparisons, the association with the 142V and 486V variant alleles were significant and the 65L variant trended towards significance. The strongest signal for an effect on outcome was with 486V and data suggest treatment with a β-blocker may alleviate some of this risk in participants with this variant. Finally, a gene-gene interaction may exist, whereby ADRB1 R389G status may influence the effect of GRK4 polymorphisms on BP response to atenolol and risk for adverse cardiovascular events.

GRK4 65L and 142V were associated with reduced BP response to atenolol in both Caucasians and African Americans. Similar results were observed with haplotype analysis, with increasing copies of the variant 65L-142V haplotype associated with diminished BP response. We hypothesized that a pharmacogenetic effect would be evident with atenolol, since its protein target, β1-AR, is a GPCR and could be affected by GRK4. The 486V variant was associated with decreased response to atenolol in Caucasians, however the PEAR trial contained a limited number of African Americans with the 486V variant, limiting power to detect statistically significant differences in this sample. BP response by GRK4 genotype or haplotype achieved statistical significance in the combined analysis but statistical significance was not always achieved when analyzed by ethnic group. However, given that strong trends were present in the separate race groups, this is likely explained by the reduced power when the race groups were analyzed separately. These results are mechanistically consistent with the hypothesis suggesting GRK4 variants increase β1-AR phosphorylation. Since these variant alleles essentially result in gain of function, they may desensitize β1-ARs, creating the equivalent of endogenous β-blockade, a term previously attributed to a similar functional SNP in GRK526, thus representing a genotype less responsive to β-blockers.

Currently, few human studies focusing on GRK4 SNPs have been published, and disagreements between these studies have been noted. The 65L variant has been associated with elevated BP in normotensive twins25, 27 and with salt sensitive hypertension28. The 142V variant has been reported by some studies to be associated with hypertension24, 28, 29, while others have suggested that it is not25, 30. Some studies have reported that the 486V allele is associated with hypertension24, 28, 31, while others implicate the 486A allele as the causative variant25, 29, 32. This gene or these SNPs have not arisen from the large genome-wide association studies in hypertension, so it is possible they do not play an important role in causing hypertension.

The only other pharmacogenetic analysis of GRK4 was from the AASK trial, which included only African Americans11. There are important differences comparing AASK and PEAR however. The AASK phenotype was time to BP control (which might be a surrogate for BP response), whereas we analyzed the actual BP response. The AASK investigators observed that in participants taking metoprolol, those with both the 65L and 142A alleles took longer to achieve BP control than participants without this genotype combination. The AASK findings were significant only for males of African descent, who generally have a poor response to β-blockers. We found a similar effect with 65L, but with 142V instead of 142A, and the associations in our study were consistent across race and gender.

Our data also suggest GRK4 variant alleles may contribute to increased risk for adverse cardiovascular outcomes. In a “by genotype” analysis, all three GRK4 variants increased risk in an additive fashion in Caucasians and Hispanics, with 486V variant homozygotes reaching statistical significance and 65L and 142V homozygotes, trending towards significance. When analyzed for risk per variant allele, point estimates for all three GRK4 variants displayed an increased risk, with the 486V variant displaying the greatest effect. When examined by treatment strategy, 65L and 142V variants were associated with similar outcomes for pooled Caucasians and Hispanics participants in both β-blocker and CCB based strategies. However, compared to the main effect analysis, increasing copies of 486V resulted in higher odd ratios for Caucasian and Hispanic participants in the CCB based strategy and reduced risk in the β-blocker based strategy. The increased risk associated with GRK4 variants appeared to be driven predominantly by occurrence of death and nonfatal MI (data not shown). Unfortunately, there was a limited number of African Americans present in the INVEST case-control cohort, thus preventing us from being able to assess the effect of GRK4 polymorphisms on the primary outcome in this race group.

GRK4 65L and 142V variants exhibited their most profound effects on BP response to atenolol, while 486V predominantly affected cardiovascular outcomes. While further in vitro experiments are necessary to elucidate the reasons for this difference in effects, it may be related to the fact that these variants are located in separate functional domains of GRK4, with the 65L and 142V variants located within the GPCR interacting region and the 486V variant located within the membrane targeting region8. Additionally, the INVEST trial design allowed for addition of other antihypertensive drugs to achieve a target BP control, thus reducing the ability to detect BP driven associations for a single drug.

We have considered that the pharmacogenetic effect may be mediated by interaction of the β1-AR (or possibly β2-AR) and GRK4 proteins. Our finding that associations with BP response and CV outcomes were generally stronger in the most active β1AR 389R-homozygote group supports the concept that GRK4 phosphorylates β1AR. Two GRK4 variants, 65L and 142V, were associated with decreased response to atenolol in Caucasians who were ADRB1 389R homozygotes, but not 389G-carriers. When analyzed by ADRB1 R389G genotype status, increased risk associated with GRK4 142V was only observed in ADRB1 389R-homozygotes, but not 389G-carriers. However, increased risk associated with GRK4 486V was observed in both ADRB1 389R-homozygotes and 389G-carriers. These data suggest potential regulation of β1AR by GRK4, with greater effects seen with the more active 389R form of the β1AR. However, the lack of a statistically significant interaction term represents a limitation of this study. Additional studies will be required to specifically address the mechanistic basis of the current findings.

GRK4 was among our original candidate genes20 and the current study was aimed at replicating previous associations in β-blocker pharmacogenomics, however, our study is limited by the fact that the data derive from a candidate gene chip. While our data achieve statistical significance for the number of SNPs tested in the analysis, they do not meet chip-wide Bonferroni corrected significance. Further in vitro studies as well as replication of our genetic associations are needed in order to confirm the results of this study and to provide mechanistic insights into how the polymorphisms examined affect GRK4 function.

Supplementary Material

Perspectives.

Patient response to antihypertensive therapy is highly variable, and it is likely that some of this variability is due to genetic factors1. Our data contribute to the growing body of literature demonstrating how individual genetic differences may affect BP response to β-blockers. Data from this study suggest three nonsynonymous polymorphisms in GRK4 (R65L, A142V and A486V) diminish BP response to atenolol. Our data also show that Caucasian and Hispanic participants have an increased risk for adverse cardiovascular events when they are homozygous for these GRK4 variant alleles. Finally, our data suggest that these effects may be due in part to interactions between GRK4 and β1 AR, since the effects of GRK4 variant alleles were more pronounced in participants who were also ADRB1 389R-homozygotes. While it is not yet known whether GRK4 and β1 AR directly interact, GRK4 has been shown to interact with a wide variety of other GPCRs4, 6, 10, 33 and β1AR has been shown to be regulated by other GRKs. Additional replication and further functional studies are needed in order to better understand the role of GRK4 in regulating atenolol response.

Novelty and Significance: 1) What is New, 2) What is Relevant?

1) What is New?

Three nonsynonymous SNPs in GRK4 (R65L, A142V, and A486V) affect BP response to atenolol and impact risk for experiencing adverse cardiovascular events.

2) What is Relevant?

The efficacy of β-blockers in treating hypertension is highly variable and this research sheds some light on potential reasons for that variability.

3) Summary

Nonsynonymous SNPs (R65L, A142V, and A486V) in GRK4 negatively affect BP response to atenolol.

The variant alleles of these SNPs also increase the risk of adverse cardiovascular events. These observations may be due in part to interactions between GRK4 and the β1AR.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

This work is supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD), grant U01 GM074492, funded as part of the Pharmacogenetics Research Network. Additional support for this work includes: National Institutes of Health grants R01 HL74730, K23 grants HL091120 (A.L. Beitelshees) and HL086558 (R.M. Cooper-DeHoff); NIH CTSA grants UL1- RR092890 (University of Florida), UL1-RR025008 (Emory University), and UL1-RR024150 (Mayo Clinic); and grants from Abbott Laboratories, the University of Florida Opportunity Fund, and the Mayo Foundation.

We thank the PEAR study physicians Drs. George Baramidze, Carmen Bray, Kendall Campbell, R. Whit Curry, Frederic Rabari-Oskoui, Dan Rubin, and Seigfried Schmidt. We also thank all of the INVEST site investigators. Finally, we thank all the participants who participated in PEAR and INVEST-GENES.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest/Disclosures

Drs. Johnson, Pepine, Cooper-DeHoff, and Langaee have received funding from Abbott Laboratories.

References

- 1.Materson BJ, Reda DJ, Cushman WC, Massie BM, Freis ED, Kochar MS, Hamburger RJ, Fye C, Lakshman R, Gottdiener J, Ramirez EA, Henderson WG. Single-drug therapy for hypertension in men. A comparison of six antihypertensive agents with placebo. The department of veterans affairs cooperative study group on antihypertensive agents. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:914–921. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304013281303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Penela P, Murga C, Ribas C, Tutor AS, Peregrin S, Mayor F., Jr Mechanisms of regulation of g protein-coupled receptor kinases (grks) and cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;69:46–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohn HI, Xi Y, Pesant S, Harris DM, Hyslop T, Falkner B, Eckhart AD. G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 expression and activity are associated with blood pressure in black americans. Hypertension. 2009;54:71–76. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.125955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Felder RA, Sanada H, Xu J, Yu PY, Wang Z, Watanabe H, Asico LD, Wang W, Zheng S, Yamaguchi I, Williams SM, Gainer J, Brown NJ, Hazen-Martin D, Wong LJ, Robillard JE, Carey RM, Eisner GM, Jose PA. G protein-coupled receptor kinase 4 gene variants in human essential hypertension. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:3872–3877. doi: 10.1073/pnas.062694599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keys JR, Zhou RH, Harris DM, Druckman CA, Eckhart AD. Vascular smooth muscle overexpression of g protein-coupled receptor kinase 5 elevates blood pressure, which segregates with sex and is dependent on gi-mediated signaling. Circulation. 2005;112:1145–1153. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.531657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Premont RT, Macrae AD, Stoffel RH, Chung N, Pitcher JA, Ambrose C, Inglese J, MacDonald ME, Lefkowitz RJ. Characterization of the g protein-coupled receptor kinase grk4. Identification of four splice variants. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:6403–6410. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.11.6403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dzimiri N, Muiya P, Andres E, Al-Halees Z. Differential functional expression of human myocardial g protein receptor kinases in left ventricular cardiac diseases. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;489:167–177. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Felder RA, Jose PA. Mechanisms of disease: The role of grk4 in the etiology of essential hypertension and salt sensitivity. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2006;2:637–650. doi: 10.1038/ncpneph0301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watanabe H, Xu J, Bengra C, Jose PA, Felder RA. Desensitization of human renal d1 dopamine receptors by g protein-coupled receptor kinase 4. Kidney Int. 2002;62:790–798. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Villar VA, Jones JE, Armando I, Palmes-Saloma C, Yu P, Pascua AM, Keever L, Arnaldo FB, Wang Z, Luo Y, Felder RA, Jose PA. G protein-coupled receptor kinase 4 (grk4) regulates the phosphorylation and function of the dopamine d3 receptor. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:21425–21434. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.003665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhatnagar V, O’Connor DT, Brophy VH, Schork NJ, Richard E, Salem RM, Nievergelt CM, Bakris GL, Middleton JP, Norris KC, Wright J, Hiremath L, Contreras G, Appel LJ, Lipkowitz MS. G-protein-coupled receptor kinase 4 polymorphisms and blood pressure response to metoprolol among african americans: Sex-specificity and interactions. Am J Hypertens. 2009;22:332–338. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2008.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson JA, Zineh I, Puckett BJ, McGorray SP, Yarandi HN, Pauly DF. Beta 1-adrenergic receptor polymorphisms and antihypertensive response to metoprolol. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2003;74:44–52. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9236(03)00068-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu J, Liu ZQ, Yu BN, Xu FH, Mo W, Zhou G, Liu YZ, Li Q, Zhou HH. Beta1-adrenergic receptor polymorphisms influence the response to metoprolol monotherapy in patients with essential hypertension. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2006;80:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sofowora GG, Dishy V, Muszkat M, Xie HG, Kim RB, Harris PA, Prasad HC, Byrne DW, Nair UB, Wood AJ, Stein CM. A common beta1-adrenergic receptor polymorphism (arg389gly) affects blood pressure response to beta-blockade. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2003;73:366–371. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9236(02)17734-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mialet Perez J, Rathz DA, Petrashevskaya NN, Hahn HS, Wagoner LE, Schwartz A, Dorn GW, Liggett SB. Beta 1-adrenergic receptor polymorphisms confer differential function and predisposition to heart failure. Nat Med. 2003;9:1300–1305. doi: 10.1038/nm930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Terra SG, Hamilton KK, Pauly DF, Lee CR, Patterson JH, Adams KF, Schofield RS, Belgado BS, Hill JA, Aranda JM, Yarandi HN, Johnson JA. Beta1-adrenergic receptor polymorphisms and left ventricular remodeling changes in response to beta-blocker therapy. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2005;15:227–234. doi: 10.1097/01213011-200504000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liggett SB, Cresci S, Kelly RJ, Syed FM, Matkovich SJ, Hahn HS, Diwan A, Martini JS, Sparks L, Parekh RR, Spertus JA, Koch WJ, Kardia SL, Dorn GW., 2nd A grk5 polymorphism that inhibits beta-adrenergic receptor signaling is protective in heart failure. Nat Med. 2008;14:510–517. doi: 10.1038/nm1750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang WC, Mihlbachler KA, Bleecker ER, Weiss ST, Liggett SB. A polymorphism of g-protein coupled receptor kinase5 alters agonist-promoted desensitization of beta2- adrenergic receptors. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2008;18:729–732. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e32830967e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rathz DA, Gregory KN, Fang Y, Brown KM, Liggett SB. Hierarchy of polymorphic variation and desensitization permutations relative to beta 1- and beta 2-adrenergic receptor signaling. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:10784–10789. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206054200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson JA, Boerwinkle E, Zineh I, Chapman AB, Bailey K, Cooper-DeHoff RM, Gums J, Curry RW, Gong Y, Beitelshees AL, Schwartz G, Turner ST. Pharmacogenomics of antihypertensive drugs: Rationale and design of the pharmacogenomic evaluation of antihypertensive responses (pear) study. Am Heart J. 2009;157:442–449. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pepine CJ, Handberg-Thurmond E, Marks RG, Conlon M, Cooper-DeHoff R, Volkers P, Zellig P. Rationale and design of the international verapamil sr/trandolapril study (invest): An internet-based randomized trial in coronary artery disease patients with hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32:1228–1237. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00423-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beitelshees AL, Gong Y, Wang D, Schork NJ, Cooper-Dehoff RM, Langaee TY, Shriver MD, Sadee W, Knot HJ, Pepine CJ, Johnson JA. Kcnmb1 genotype influences response to verapamil sr and adverse outcomes in the international verapamil sr/trandolapril study (invest) Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2007;17:719–729. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e32810f2e3c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pacanowski MA, Gong Y, Cooper-Dehoff RM, Schork NJ, Shriver MD, Langaee TY, Pepine CJ, Johnson JA. Beta-adrenergic receptor gene polymorphisms and beta-blocker treatment outcomes in hypertension. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;84:715–721. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Speirs HJ, Katyk K, Kumar NN, Benjafield AV, Wang WY, Morris BJ. Association of g-protein- coupled receptor kinase 4 haplotypes, but not hsd3b1 or ptp1b polymorphisms, with essential hypertension. J Hypertens. 2004;22:931–936. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200405000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhu H, Lu Y, Wang X, Treiber FA, Harshfield GA, Snieder H, Dong Y. The g protein-coupled receptor kinase 4 gene affects blood pressure in young normotensive twins. Am J Hypertens. 2006;19:61–66. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lindgren P, Buxton M, Kahan T, Poulter NR, Dahlof B, Sever PS, Wedel H, Jonsson B. Cost-effectiveness of atorvastatin for the prevention of coronary and stroke events: An economic analysis of the anglo-scandinavian cardiac outcomes trial--lipid-lowering arm (ascot-lla) Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2005;12:29–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhu H, Lu Y, Wang X, Snieder H, Treiber FA, Harshfield GA, Dong Y. The g protein-coupled receptor kinase 4 gene modulates stress-induced sodium excretion in black normotensive adolescents. Pediatr Res. 2006;60:440–442. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000238250.64591.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanada H, Yatabe J, Midorikawa S, Hashimoto S, Watanabe T, Moore JH, Ritchie MD, Williams SM, Pezzullo JC, Sasaki M, Eisner GM, Jose PA, Felder RA. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms for diagnosis of salt-sensitive hypertension. Clin Chem. 2006;52:352–360. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.059139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Y, Li B, Zhao W, Liu P, Zhao Q, Chen S, Li H, Gu D. Association study of g protein-coupled receptor kinase 4 gene variants with essential hypertension in northern han chinese. Ann Hum Genet. 2006;70:778–783. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2006.00278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Staessen JA, Kuznetsova T, Zhang H, Maillard M, Bochud M, Hasenkamp S, Westerkamp J, Richart T, Thijs L, Li X, Brand-Herrmann SM, Burnier M, Brand E. Blood pressure and renal sodium handling in relation to genetic variation in the drd1 promoter and grk4. Hypertension. 2008;51:1643–1650. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.109611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bengra C, Mifflin TE, Khripin Y, Manunta P, Williams SM, Jose PA, Felder RA. Genotyping of essential hypertension single-nucleotide polymorphisms by a homogeneous pcr method with universal energy transfer primers. Clin Chem. 2002;48:2131–2140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gu D, Su S, Ge D, Chen S, Huang J, Li B, Chen R, Qiang B. Association study with 33 single-nucleotide polymorphisms in 11 candidate genes for hypertension in chinese. Hypertension. 2006;47:1147–1154. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000219041.66702.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pitcher JA, Fredericks ZL, Stone WC, Premont RT, Stoffel RH, Koch WJ, Lefkowitz RJ. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (pip2)-enhanced g protein-coupled receptor kinase (grk) activity. Location, structure, and regulation of the pip2 binding site distinguishes the grk subfamilies. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:24907–24913. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.40.24907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.