Abstract

The amplitude of the depolarization-evoked Ca2+ transient is larger in dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons from tumor-bearing mice compared with that of neurons from naive mice, and the change is mimicked by coculturing DRG neurons with the fibrosarcoma cells used to generate the tumors (Khasabova et al., 2007). The effect of palmitoylethanolamide (PEA), a ligand for the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα), was determined on the evoked-Ca2+ transient in the coculture condition. The level of PEA was reduced in DRG cells from tumor-bearing mice as well as those cocultured with fibrosarcoma cells. Pretreatment with PEA, a synthetic PPARα agonist (GW7647), or ARN077, an inhibitor of the enzyme that hydrolyzes PEA, acutely decreased the amplitude of the evoked Ca2+ transient in small DRG neurons cocultured with fibrosarcoma cells. The PPARα antagonist GW6471 blocked the effect of each. In contrast, the PPARα agonist was without effect in the control condition, but the antagonist increased the amplitude of the Ca2+ transient, suggesting that PPARα receptors are saturated by endogenous ligand under basal conditions. Effects of drugs on mechanical sensitivity in vivo paralleled their effects on DRG neurons in vitro. Local injection of ARN077 decreased mechanical hyperalgesia in tumor-bearing mice, and the effect was blocked by GW6471. These data support the conclusion that the activity of DRG neurons is rapidly modulated by PEA through a PPARα-dependent mechanism. Moreover, agents that increase the activity of PPARα may provide a therapeutic strategy to reduce tumor-evoked pain.

Introduction

Understanding the effect of cancer cells on somatosensory neurons is fundamental to resolving the generation of tumor-evoked pain because these neurons directly innervate the tumor environment, and tumor-evoked pain is a debilitating factor in the quality of life of patients with advanced cancer (Meuser et al., 2001). Although tumor-evoked pain shares some underlying mechanisms with inflammatory and neuropathic pain, dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons from tumor-bearing mice have a unique phenotype (Honore et al., 2000). Using an in vitro model of DRG cells cocultured with cancer cell lines, we (Khasabova et al., 2007, 2008) and others (Chizhmakov et al., 2009; Schweizerhof et al., 2009) have shown that medium conditioned by cancer cells causes long-term changes in membrane proteins that underlie the transduction of excitatory stimuli in DRG neurons. Importantly, changes in membrane proteins in vitro mirror changes in DRGs that innervate the tumor-bearing region in vivo. One change that occurs is an increase in the expression of the enzyme that hydrolyzes the endocannabinoid N-arachidonoyl-ethanolamide [anandamide (AEA)].

In DRG neurons, AEA activates the cannabinoid type 1 receptor (CB1R), and activity of this receptor attenuates the excitability of nociceptors (Agarwal et al., 2007). Mechanical hyperalgesia in tumor-bearing mice is associated with a decrease in AEA in DRGs that innervate the region of the tumor (Khasabova et al., 2011). An increase in mRNA for fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH), the enzyme that catabolizes AEA, contributes to the decrease in AEA (Khasabova et al., 2008).

Palmitoylethanolamide (PEA) is synthesized from the same class of membrane phospholipids, the N-acylphosphatidylethanolamines, that are precursors for AEA (Cadas et al., 1996, 1997). PEA is primarily catabolized by N-acylethanolamine-hydrolyzing acid amidase (NAAA) (Tsuboi et al., 2004) but is also a substrate for FAAH (Lichtman et al., 2002). PEA is an agonist at the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) but has no activity at the CB1R (LoVerme et al., 2005, 2006).

PPARα is a member of the nuclear receptors superfamily. There is keen interest in the ability of PPARα agonists to inhibit the development of inflammation through PPARα regulation of gene expression (O'Sullivan and Kendall, 2010). In animal models of peripheral inflammation, PPARα agonists are both anti-inflammatory and analgesic (Calignano et al., 1998, 2001; LoVerme et al., 2005, 2006; Sagar et al., 2008). The rapid time course underlying the antihyperalgesic properties of the compounds suggests PPARα mediates transcription-independent effects, but in vivo experiments cannot resolve whether reductions in hyperalgesia are direct effects of the drugs on sensory neurons or secondary to the effects of the drugs on the immune system.

Initially, we determined that medium conditioned by fibrosarcoma cells decreased the basal level of PEA in primary cultures of murine DRG cells. A functional consequence of the decrease in PEA was explored by determining the effect of PPARα ligands on the depolarization-evoked Ca2+ transient in DRG neurons cocultured with fibrosarcoma cells. Evidence that PPARα agonists and antagonists modulated nociception in naive and tumor-bearing mice in parallel with effects in vitro supports the utility of PPARα agonists in the management of cancer pain.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

Adult, male C3H/He mice (National Cancer Institute; 25–30 g) were used in the studies. This strain is syngeneic to the fibrosarcoma cells used in the coculture condition. All procedures were approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. To generate tumor-bearing mice, fibrosarcoma cells (2 × 105 cells in 10 μl of PBS, pH 7.3) were injected into and around the calcaneus bone of the animal's left hindpaw while the mouse was anesthetized with isoflurane (2%). The development of tumors over the course of 10 d results in bone osteolysis and mechanical hyperalgesia (Wacnik et al., 2001; Khasabova et al., 2007).

Culture of DRG cells.

Following killing, DRGs were dissected from all levels of the spinal cord of naive adult male mice. After enzymatic and mechanical dissociation, the final cell suspension of neurons and supporting cells was plated on laminin-coated glass coverslips (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at a density of 10,000 cells/25 mm2. Cells were maintained in 5 ml of Ham's F12/DMEM medium supplemented with l-glutamine (2 mm), glucose (40 mm), penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), and DNAase I (0.15 mg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C for 40–48 h before use (Khasabova et al., 2007). DRG samples were similarly prepared for the coculture model.

DRG cell–fibrosarcoma cell coculture.

Cells from the murine NCTC clone 2472 fibrosarcoma cell line (American Type Culture Collection) were plated on glass coverslips at a density of 50,000 cells/25 mm2 in the DRG culture medium (minus the DNAase) and maintained in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C. After 3 d in vitro, a coverslip with freshly dissociated DRG cells was combined in one Petri dish with a coverslip of preplated fibrosarcoma cells. Cells were maintained in 3 ml of fresh Ham's F12/DMEM with 2 ml of fibrosarcoma cell-conditioned medium at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 as previously described (Khasabova et al., 2007).

Quantification of AEA, PEA, and 2-arachidonoyl-sn-glycerol.

DRGs L3–L5 (three DRGs/sample, ipsilateral to tumors in tumor-bearing mice) were removed from mice following euthanasia under a surgical level of isoflurane-induced anesthesia. Samples were rapidly weighed, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until the time of processing. Samples of cultured DRG cells (one coverslip/sample) were processed after 48 h in vitro. Processing began with extraction of lipids in 5 vol of chloroform containing 5 pmol of d8-AEA, 100 pmol of d4-PEA, and 100 pmol of d8-2-arachidonoyl-sn-glycerol (d8-2-AG) (Cayman Chemical) as internal standards. Extraction of lipids proceeded overnight at 4°C. Mixtures were then homogenized with an equal volume of methanol/Tris-HCl (50 mm) (1:1). Homogenates were centrifuged at 3000 × g for 15 min at 4°C; the aqueous phase plus debris were collected and extracted again with 1 vol of chloroform. The organic phases were pooled and evaporated with a gentle stream of nitrogen gas. Vials containing the dried samples were stored at −80°C until analyzed. Targeted isotope-dilution HPLC/atmospheric pressure chemical ionization/mass spectrometry was conducted on each sample. A ZORBAX SB-C18 (0.5 × 150 mm) column was used. The column was maintained at 40°C. The mobile phase A was 0.1% formic acid in 2 mm ammonium acetate, and phase B was 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile. The flow rate was 10 μl/min with a gradient that began with 50% A/50% B. The AEA, PEA, and 2-AG levels in unknown samples were estimated from the ratio of the area of the signals of deuterated and nonlabeled standards of AEA (0.02–20 pmol), PEA (0.2–200 pmol), or 2-AG (0.2–200 pmol). Data are expressed as moles of AEA, PEA, or 2-AG per sample.

Measurement of the concentration of free intracellular calcium.

The depolarization-evoked Ca2+ transient was used as the bioassay to measure responses of DRG neurons under experimental conditions. As previously described (Khasabova et al., 2007), the free intracellular calcium ([Ca2+]i) was measured using a dual-emission microfluorimeter (Photoscan; Photon Technology International) to monitor the fluorescence of indo-1 (Invitrogen) that binds to intracellular Ca2+. The preparation was continuously superfused with HEPES buffer at a rate of 1.8 ml/min. The HEPES buffer contained 25 mm HEPES, 135 mm NaCl, 2.5 mm CaCl2, 3.5 mm KCl, 1 mm MgCl2, and 3.3 mm glucose and 0.1% bovine serum albumin. When the buffer was adjusted to 30 and 50 mm KCl, the osmolality of NaCl was decreased to match the increase in KCl osmolality. The pH of the final solution was adjusted to 7.4, and the osmolality was adjusted to 335–340 mOsm with sucrose.

Only one neuron on each coverslip was assayed. The maximum and minimum diameters of each neuron were estimated using a grid mounted in the eyepiece of the microscope, and the average was used to calculate somal area. Only neurons <500 μm2 were selected and are referred to as small in this report. Small neurons are most likely to be nociceptive (Hiura and Sakamoto, 1987; Pearce and Duchen, 1994).

During measures of the indo-1 fluorescence, counts from the photomultiplier tubes were summed over 1.5 s and recorded on a computer. Values for the [Ca2+]i were calculated using the equation [Ca2+]i = KDβ(R − Rmin)/(Rmax − R), where R = 405 nm/485 nm fluorescence emission ratio corrected for background fluorescence. The dissociation constant (KD) for indo-1 is 250 nm (Grynkiewicz et al., 1985), and β was the ratio of fluorescence at 485 nm in the absence and presence of a saturating concentration of Ca2+. Values for the remaining constants were empirically determined in adult murine DRG neurons: Rmin = 0.275; Rmax = 4.73.

A stable baseline in the [Ca2+]i for each neuron was obtained during superfusion with HEPES buffer before testing responses to chemical stimuli. A coverslip was superfused with only one drug or drug combination before testing the response to 30 mm KCl (10 s). In preliminary studies, this concentration of KCl evoked a Ca2+ transient in 50% of the neurons tested. This frequency of response was chosen to allow the detection of an increase or decrease in the occurrence of a transient. The threshold for defining the occurrence of a Ca2+ transient was an increase in the [Ca2+]i >50% of the basal [Ca2+]i. If the change in the [Ca2+]i did not meet this threshold (defined as no response), the neuron was superfused with 50 mm KCl to check the viability of the neuron. Neurons that did not elicit a Ca2+ transient in response to 50 mm KCl were excluded from the data set. The frequency of response to 30 mm KCl was defined as a percentage [(number of neurons that responded/number of neurons tested) × 100%]. The amplitude of the Ca2+ transient was defined as the difference in [Ca2+]i measured at the peak minus the average baseline sampled 2 min before superfusion with the test substance. Recordings were generally terminated after reliable determination of a peak response so data for return of the [Ca2+]i to baseline were not routinely obtained.

Quantification of mRNA by real-time PCR.

DRGs L3–L5 (three DRGs/sample, ipsilateral to tumors in tumor-bearing mice) were isolated from mice, placed in RNAlater (QIAGEN) and stored at 4°C. Total RNA was isolated from samples using RNeasy Lipid Tissue Mini Kits (QIAGEN). RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using QuantiTect RT-PCR kits (QIAGEN) as per the manufacturer's instructions. Real-time PCR studies were performed with DyNAmo HS SYBR Green Master Mix (Finnzymes) using the DNA engine Opticon 2 (MJ Research) through 45 PCR cycles (94°C for 10 s, 57°C for 20 s, 72°C for 30 s). Each cDNA sample was run in triplicate for murine PPARα, NAAA, and the reference gene (S15). Primer pair sequences were as follows: PPARα (GenBank accession number NM_011144.3), forward primer, 5′-AGT GCA TGT CCG TGG AGA C-3′, and reverse primer, 5′-TCA AGG AGG ACA GCA TCG T-3′; NAAA (NM_025972), forward primer, 5′-TTC GAA GCA GCT GTC TAC AC-3′, and reverse primer, 5′-AGA GGG TCA AGA GGC CAA ATG T-3′; S15 (BC094409), forward primer, 5′-CCG AAG TGG AGC AGA AGA AG-3′, and reverse primer, 5′-CTC CAC CTG GTT GAA GGT C-3′. All primers were synthesized by Operon Biotechnologies. Specificity of each amplicon was confirmed by melting curve analysis, evidence of a single band after gel electrophoresis, authenticity of the DNA sequence of the band isolated from the gel, and resolution by BLAST analysis that the sequence of the amplicon was unique to each target. The efficiency of the primer set was derived from the slope of the line generated from the serial dilution of a sample using the following equation: efficiency = 10(−1/slope). Within each primer set, all DRG samples were assayed in triplicate at the same dilution, and all data were within the linear range used to determine the efficiency of the primers. For each primer set, the change in critical threshold for each sample [ΔC(t)] was calculated by subtracting the average C(t) for the sample from the mean of the C(t) for the naive subjects such that the ΔC(t) is a positive number when there is an increase in mRNA. Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM for the treatment group. Using this analysis, there was no difference between the naive and tumor-bearing animals in the level of mRNA for the reference gene [ΔC(t), naive, 0.000 ± 0.417; tumor-bearing, −0.059 ± 0.180; p = 0.90].

Measurement of [3H]PEA hydrolysis.

PEA hydrolysis was measured in primary cultures of DRG neurons (approximately three to four DRGs/coverslip) after 44–48 h in vitro. Coverslips containing dissociated DRGs were placed in HEPES buffer with vehicle (0.095% ethanol, final concentration) or ARN077 (1 μm) for 30 min. To model physiological experiments in vitro, coverslips were then placed in 0.5 ml of Tris buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, 3 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mg/ml fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin, pH 7.4). The pH of 7.4 is approximately midway between the optimum pH for NAAA (pH 5) and FAAH (pH 9) (Tsuboi et al., 2004). Because AEA can compete with the uptake of PEA (Jacobsson and Fowler, 2001), the contribution of cellular uptake to the measure of exogenous PEA hydrolysis was excluded by subjecting samples to two freeze–thaw cycles. Following the second thaw, samples were incubated for 30 min at 37°C with [3H]PEA (50,000 dpm/sample; American Radiolabeled Chemicals). Preliminary studies confirmed that, under these conditions, [3H]PEA hydrolysis was within the linear range with respect to time. The enzyme reaction was stopped by the addition of 2 ml of chloroform/methanol (1:2). After standing at room temperature for 30 min, the phases were separated with the addition of 0.67 ml of chloroform and 0.6 ml of water and centrifugation at 280 × g for 15 min. The amount of [3H] in 0.5 ml of each of the aqueous and organic phases was determined using liquid scintillation spectrometry. PEA hydrolysis was expressed as a percentage of total [3H]PEA, taking into account that the radioactivity in the aqueous phase was [3H]ethanolamine, whereas [3H]PEA remained in the organic phase.

Assessment of mechanical sensitivity.

Before inclusion in the study, daily baseline measurements of withdrawal frequency to a monofilament that delivered a force of 3.9 mN were obtained for all mice on 3 consecutive days. Mice were isolated under separate glass containers on a mesh platform and allowed to acclimate for 30 min before testing. The monofilament was applied to the plantar surface of each hindpaw 10 times (1–2 s each). The number of withdrawal responses was determined and expressed as a percentage of the number of stimuli applied (withdrawal frequency). These data were used to screen mice for hypersensitivity, and animals that exhibited baseline withdrawal frequencies ≥50% were excluded from the study (<2%).

The effect of the NAAA inhibitor and PPARα antagonist on the sensitivity of the hindpaws of naive mice was assessed using a repetitive stimulation paradigm (Joseph et al., 2003). Four von Frey monofilaments with ascending bending forces of 3.9, 5.9, 9.8, and 13.7 mN were used. The frequency of withdrawal to each mechanical stimulus was determined in each hindpaw before and 1 h after intraplantar injection of ARN077, GW6471, or vehicle (10 μl volume) into one hindpaw. The dose of ARN077 was the maximum dose that was soluble in the vehicle (5% ethanol in saline). The dose of GW6471 was the maximum dose tested that did not have a systemic effect on mechanical sensitivity following intraplantar injection in naive mice.

The effect of drugs on mechanical hyperalgesia in tumor-bearing mice was determined on day 10 after implantation of fibrosarcoma cells using the von Frey monofilament that delivered a force of 3.9 mN. Mechanical hyperalgesia was defined as an increase in the frequency of paw withdrawal responses. Only mice exhibiting mechanical hyperalgesia (≥50% withdrawal frequency) were included in subsequent experiments (∼85%). To determine the acute, local antihyperalgesic effect of drugs, mice were given an intraplantar injection of drug (10 μl volume) into one hindpaw. Withdrawal responses evoked by the monofilament were measured in each hindpaw before and every 30 min after injection for 2 h. At least two treatment groups were used on each day of behavioral testing; on the following day, the treatment groups were switched on the same mice. No mouse received more than two drug injections. There were no differences in results for any one treatment between the 2 d. In all behavioral experiments, the individual judging behavioral responses was blinded to the treatment of each subject.

Western blot analysis of PPARα protein.

Mechanical hyperalgesia was confirmed in tumor-bearing mice 10 d after implantation of fibrosarcoma cells in the calcaneous bone and before killing by decapitation under a surgical level of isoflurane anesthesia. DRGs L3–L5 from naive and tumor-bearing mice (six DRGs/sample pooled from two mice) and tibial nerve (∼1 cm, pooled from two mice) were collected, frozen on dry ice, and stored at −80°C. Samples from tumor-bearing mice were ipsilateral to tumors. Samples were sonicated in single-detergent lysis buffer [50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, with 1% Triton X-100, 150 mm NaCl, 0.02% Na azide, 100 μg/ml PMSF, and 1 μg/ml protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma-Aldrich)], and the particulate fraction of the supernatant was obtained after serial centrifugation at 800 × g for 10 min and 14,000 × g for 25 min. Western blot analysis was performed on 15 μg of protein, which was loaded onto a 10% SDS-PAGE gel, subjected to electrophoresis, and then transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Nonspecific binding to membranes was blocked by incubation in PBS with 3% defatted dry milk for 1 h at room temperature. The membranes were probed with a rabbit anti-PPARα antibody (1:500; Thermo Fisher Scientific) overnight at 4°C. Specificity of the antibody was determined by preabsorption of the diluted antibody with 1 μg/ml PPARα synthetic immunizing peptide (Affinity BioReagents). Detection was performed using a peroxidase conjugate of goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:10,000; Sigma-Aldrich). Immunoreactivity was visualized using a chemiluminescent reagent (Pierce). Loading controls were performed with a mouse anti-β-tubulin antibody (1:10,000; Sigma-Aldrich). The optical density of each immunoreactive band was determined using MetaMorph software. The amount of PPARα protein was defined as the ratio of PPARα-ir to tubulin-ir within the same sample.

Drug treatments.

PPARα ligands were purchased from Tocris Biosciences, dissolved in ethanol, and stored at −20°C. The stock concentration of the PPARα agonist 2-(4-(2-(1-cyclohexanebutyl)-3-cyclohexylureido)ethyl)phenylthio)-2-methyl-propionic acid (GW7647) was 20 mm, the concentration of PEA was 33 mm, and the concentration of the PPARα antagonist [(2S)-2-[[(1Z)-1-methyl-3-oxo-3-[4-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]-1-propenyl]amino]-3-[4-[2-(5-methyl-2-phenyl-4-oxazolyl)ethoxy]phenyl]propyl]-carbamic acid ethyl ester (GW6471) was 16 mm. Drugs were diluted to their final concentrations in HEPES buffer immediately before use. The agonists were superfused for 5 min before stimulation with KCl. The PPARα antagonist was superfused for 10 min before stimulation with KCl. The synthesis and pharmacological characterization of the NAAA inhibitor ARN077 is described previously (Armirotti et al., 2012). A stock solution of ARN077 (10 mm) was prepared in ethanol.

Statistical analyses.

Data are reported as the mean ± SEM when normally distributed. For these data, differences between treatments were determined using Student's t test or two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's posttest to determine differences between groups when groups also had equal variance. Data that did not meet these criteria were reported as the median (25th to 75th percentile range), and effects of treatments were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney rank sum test or the Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA by ranks followed by Dunn's test to determine differences between groups. Data for the frequency of response to 30 mm KCl were analyzed using Fisher's exact test. A significance level of 0.05 was the threshold for stating a treatment effect in all analyses.

Results

Medium conditioned by fibrosarcoma cells decreased the levels of PEA and AEA in DRG cells

To determine the effect of fibrosarcoma cell-conditioned medium on the levels of endocannabinoids and PEA in primary cultures of DRG cells, the amounts of these substances were compared between DRG cultures in the control condition and the coculture condition (Table 1). The level of AEA in DRG cells maintained for 48 h in medium conditioned by fibrosarcoma cells was reduced to <30% of control, and the level of PEA was reduced to <60%. The level of 2-AG was not different between the two conditions, thereby excluding the possibility that the effect of the fibrosarcoma cell-conditioned medium on the levels of AEA and PEA was due to nonspecific effects on lipid metabolism. Furthermore, it is not likely that the levels reported for the DRG cells in the coculture condition were contaminated by the fibrosarcoma cells because the levels of PEA and AEA in fibrosarcoma cells were lower than those of DRG cultures in the control condition.

Table 1.

Levels of PEA and endocannabinoids in DRG cells and fibrosarcoma cells

| Substance | PEA (pmol) | 2-AG (pmol) | AEA (fmol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DRG cells in culture | |||

| Control | 60.6 (46.0–76.8) | 17.4 (13.7–20.5) | 32 (15–57) |

| Coculture | 35.6 (28.6–38.4)* | 18.8 (14.0–20.4) | 9 (8–9)* |

| DRGs L3–L5 | |||

| Naive | 31.6 ± 3.0 | 4.74 ± 0.88 | 273 ± 42 |

| Tumor bearing | 22.6 ± 1.7** | 4.35 ± 2.39 | 151 ± 25** |

| Fibrosarcoma cells | 7.9 ± 2.6 | 417 ± 31 | 7 ± 1 |

One sample for DRG cells in culture was equivalent to cells dissociated from five to six DRGs. The data represent the median (25th to 75th percentile range; n = 6).

*Significantly different from control at p < 0.005 (Mann–Whitney rank sum test). DRGs L3–L5 from one side of a mouse were pooled to make one sample at the time of killing. Samples were ipsilateral to the tumor in tumor-bearing mice. Data represent the mean ± SEM (n = 5).

**Significantly different from naive at p < 0.05 (Student's t test). Values for fibrosarcoma cells represent the mean ± SEM (n = 3).

Importantly, the pattern of changes in fatty acid ethanolamides and 2-AG observed in the coculture model was consistent with the pattern observed in the levels of PEA and endocannabinoids in L3–L5 DRGs ipsilateral to tumors in tumor-bearing mice (Table 1). The levels of PEA and AEA, but not 2-AG, were lower in DRGs from tumor-bearing mice. To date, each biochemical change in DRG cells cocultured with fibrosarcoma cells is consistent with the change observed in DRGs from tumor-bearing mice (Khasabova et al., 2007, 2008), thereby validating the relevance of the coculture model for studying the cell biology of DRG neurons in tumor-bearing mice.

Biochemical analyses were conducted to determine whether DRG cells express NAAA. Data for quantitative RT-PCR confirmed that NAAA mRNA was measurable in DRGs, but there was no difference in the level of mRNA between naive and tumor-bearing mice [ΔC(t) for naive: 0.000 ± 0.328, n = 8; tumor bearing: 0.389 ± 0.175, n = 9; p = 0.3, Student's t test]. Experiments with [3H]PEA showed a 22% increase in [3H]PEA hydrolysis by DRG cells cocultured with fibrosarcoma cells compared with the control condition (Table 2). The novel NAAA inhibitor ARN077 was used to determine the proportion of [3H]PEA hydrolysis attributable to NAAA. ARN077 inhibits human NAAA with an IC50 of 7 nm and exerts no significant inhibitory effect toward FAAH at concentrations as high as 30 μm (Armirotti et al., 2012). ARN077 (1 μm) decreased [3H]PEA hydrolysis in DRG cells from cultures with fibrosarcoma cells by 15%. These data confirm that DRG cells express NAAA. It is noteworthy that ARN077 decreased PEA hydrolysis by DRG cells without affecting the level of AEA (Table 3), thereby confirming its target selectivity.

Table 2.

PEA hydrolysis increased in DRG cells cocultured with fibrosarcoma cells

| Culture condition | Treatment | % Hydrolysis of [3H]PEA |

|---|---|---|

| Control | Vehicle | 18.0 ± 1.1 (5) |

| Coculture | Vehicle | 23.0 ± 0.5* (6) |

| ARN077 | 19.5 ± 0.4** (6) |

Each sample was equivalent to cells dissociated from three to four DRGs. See Materials and Methods for additional experimental details. Values represent the mean ± SEM of hydrolysis of [3H]PEA; the number in parentheses is the sample size.

*Significantly different from control/vehicle at p < 0.001;

**different from coculture/vehicle at p < 0.01 (one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's t test).

Table 3.

Effect of ARN077 on PEA and endocannabinoid levels in DRG cultures from naive mice

| PEA (pmol) | AEA (fmol) | 2-AG (pmol) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 80 ± 8 | 40 ± 2 | 17.6 ± 1.6 |

| ARN077 | 142 ± 2* | 42 ± 11 | 19.3 ± 1.9 |

Each sample was equivalent to cells dissociated from five to six DRGs. Samples were maintained in vitro for 40–48 h. Culture medium was replaced with HEPES buffer prior to treatment with 1 μm ARN077 for 15 min. DRGs and medium were extracted for measures of PEA and endocannabinoids. Values represent the mean ± SEM (n = 3).

*Significantly different from control at p < 0.005 (Student's t test).

PEA attenuated the evoked Ca2+ transient via PPARα in the coculture condition

The physiological consequence of the change in PEA level in small DRG neurons was explored in a bioassay of the depolarization-evoked Ca2+ transient. A change in the Ca2+ transient evoked by 50 mm KCl was noted in our initial characterization of small DRG neurons from tumor-bearing mice and the coculture model. In both conditions, the evoked Ca2+ transient was larger in amplitude compared with the transient evoked in the control condition (Khasabova et al., 2007). Similarly, the amplitude of the Ca2+ transient evoked by 30 mm KCl, a submaximal stimulus in the present study, was more than threefold larger in the coculture condition compared with that evoked in the control condition (Table 4). In addition, the stimulus of 30 mm KCl was almost twice as likely to evoke a Ca2+ transient in small neurons in the coculture condition compared with the control condition, paralleling the change in response to 25 mm KCl in small DRG neurons from tumor-bearing mice (Khasabova et al., 2007). Since this assay was effective in resolving a change in AEA signaling through CB1R in small neurons in the cancer condition (Khasabova et al., 2008), modulation of the depolarization-evoked Ca2+ transient was used as a bioassay for acute effects of PPARα ligands on small DRG neurons in vitro.

Table 4.

Coculture of DRG neurons with fibrosarcoma cells increased the response of neurons to 30 mm KCl

| Basal [Ca2+]i (nm)a | Amplitude of Ca2+ transient (nm)a | Frequency of response to 30 mm KCl (%) | n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 86 (72–100) | 85 (58–143) | 41 | 27 |

| Coculture | 94 (70–104) | 290 (106–376)* | 71** | 55 |

All data were collected from small neurons during superfusion with vehicle (0.006% ethanol).

aData for [Ca2+]i are expressed as the median (25th to 75th percentile range).

*Different from control at p < 0.005 (Mann–Whitney rank sum test).

**Different from control at p < 0.02 (Fisher's exact test).

Because the criterion for occurrence of a Ca2+ transient was dependent upon the basal [Ca2+]i, it was important to determine whether drug treatments altered the basal [Ca2+]i. Among small neurons maintained in the coculture condition, there was no difference in the basal [Ca2+]i during superfusion with the vehicle (0.006% ethanol) or effective concentrations of PPARα ligands (H = 3.4, 5 df, p = 0.64, Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA on ranks). For example, the median [Ca2+]i was 96 nm (n = 20) in the presence of PEA (10 μm).

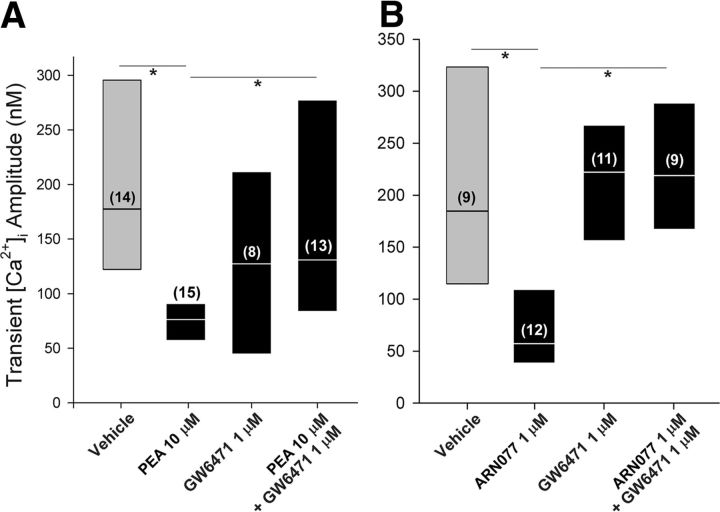

PEA (10 μm) decreased the amplitude of the depolarization-evoked Ca2+ transient in small neurons from the coculture condition by >50% compared with vehicle (Fig. 1A), and the effect of PEA was blocked by the PPARα antagonist GW6471 (H = 14.2, 3 df, p < 0.005, Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA on ranks followed by Dunn's test). PEA (10 μm) had no effect on the occurrence of the evoked Ca2+ transient in the coculture condition (75%; n = 20; p = 1.0 compared with the vehicle, Fisher's exact test).

Figure 1.

Pretreatment with PEA decreased the amplitude of the depolarization-evoked Ca2+ transient in DRG neurons cocultured with fibrosarcoma cells. A, The effect of exogenous PEA (10 μm) was blocked by pretreatment with the PPARα antagonist GW7647. B, An inhibitor of NAAA, the enzyme that degrades PEA, mimicked the effect of PEA. The label for the y-axis is the same as for A. Results are reported as the median and the 25th to 75th percentile range; the numbers in the parentheses indicate the number of neurons that responded to 30 mm KCl. *Different at p < 0.05 (Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA on ranks followed by Dunn's test).

To confirm the physiological relevance of the effect of PEA, an inhibitor of NAAA activity was used to block the degradation of PEA in DRG neurons. Treatment of primary cultures of DRG neurons with ARN077 (1 μm) for 15 min nearly doubled the level of PEA in the preparation without altering the levels of AEA and 2-AG (Table 3). Under the same conditions, pretreatment of DRG neurons with ARN077 mimicked the effect of PEA on the evoked Ca2+ transient (H = 21.0, 3 df, p < 0.001, Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA on ranks followed by Dunn's test) (Fig. 1B). Together, these data support the conclusion that PEA attenuated the amplitude of the evoked Ca2+ transient through PPARα.

A synthetic PPARα agonist attenuated the evoked Ca2+ transient in small DRG neurons cocultured with fibrosarcoma cells

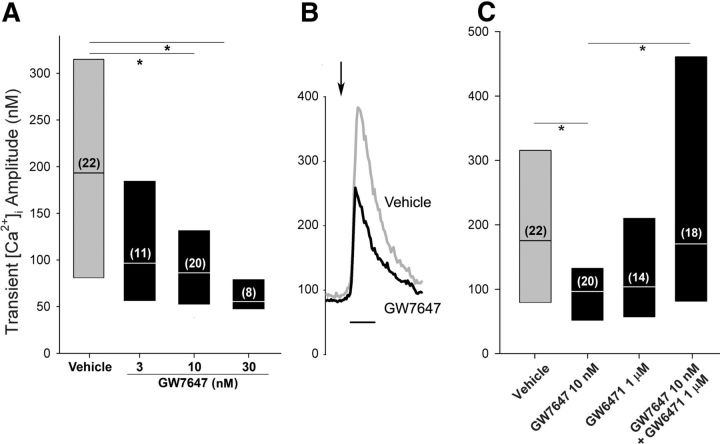

To confirm a role for PPARα in modulating the evoked Ca2+ transient, we characterized the response to a synthetic PPARα agonist. GW7647 decreased the amplitude of the Ca2+ transient evoked in DRG neurons cocultured with fibrosarcoma cells by >50% (Fig. 2A). The effect was concentration dependent with a minimum effective concentration of 10 nm (H = 14.5, 3 df, p < 0.0025, Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA on ranks followed by Dunn's test). Concentrations >30 nm were not tested because the Ca2+ transient evoked in the presence of this concentration was near the threshold for a positive response. Examples of the evoked transients in neurons in the presence of vehicle or GW7647 (10 nm) are shown in Figure 2B.

Figure 2.

A synthetic PPARα agonist decreased the amplitude of the evoked Ca2+ transient in DRG neurons cocultured with fibrosarcoma cells. A, Pretreatment with GW7647 (5 min) decreased the amplitude of the Ca2+ transient in a concentration-dependent manner. The label of the y-axis is the same for B and C. B, Examples of Ca2+ transients evoked in small neurons maintained in the coculture condition during superfusion with vehicle (gray) or 10 nm GW7647 (black). The arrow indicates the time of superfusion with 30 mm KCl. Calibration: 30 s. C, GW6471 blocked the effect of GW7647 on the Ca2+ transient. Results are reported as the median and the 25th to 75th percentile range; the numbers in the parentheses indicate the number of neurons that responded to 30 mm KCl. *Different at p < 0.05 (Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA on ranks followed by Dunn's test).

To confirm whether the effect of GW7647 on the Ca2+ transient was mediated through PPARα, neurons were treated with the PPARα antagonist GW6471 (1 μm) in conjunction with GW7647 (10 nm). Treatment with GW6471 blocked the effect of GW7647 on the amplitude of the depolarization-evoked Ca2+ transient (H = 13.3, 3 df, p < 0.005, Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA on ranks followed by Dunn's test) (Fig. 2C). GW6471 alone had no effect on the amplitude of the Ca2+ transient compared with vehicle. These data support the conclusion that the effect of GW7647 on the amplitude of the evoked Ca2+ transient was mediated through PPARα.

GW7647 (10 nm) had no effect on the frequency at which 30 mm KCl evoked a Ca2+ transient in neurons in the coculture condition (66%; n = 35; p = 0.64 compared with the vehicle, Fisher's exact test).

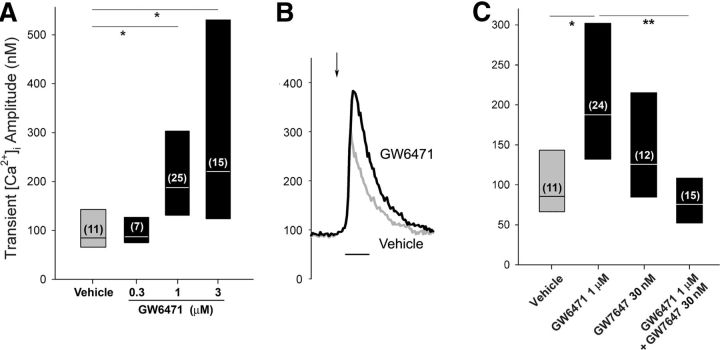

A PPARα antagonist but not agonist modulated the evoked Ca2+ transient in small DRG neurons in the control condition

Using the same concentrations that were effective in the coculture condition, neither the synthetic PPARα agonist GW7647 (30 nm) nor PEA (30 μm) altered the amplitude of the depolarization-evoked Ca2+ transient when compared with the vehicle control for DRG neurons maintained in the control condition [GW7647: median response of 125 (83–216) nm [Ca2+]i, p = 0.21, n = 11 neurons; PEA: median response of 102 (56–188) nm [Ca2+]i, p = 0.90, n = 7 neurons compared with vehicle, Mann–Whitney rank sum test]. In contrast, a concentration-dependent effect of the PPARα antagonist GW6471 on the amplitude of the Ca2+ transient was observed in the control condition (H = 14.8, 3 df, p < 0.0025 Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA on ranks followed by Dunn's test) (Fig. 3A). The minimum concentration of GW6471 that increased the amplitude of the Ca2+ transient compared with the vehicle was 1 μm. Examples of the Ca2+ transients in neurons in the presence of vehicle and GW6471 (1 μm) are shown in Figure 3B. Solubility limited the ability to test concentrations >3 μm to determine a maximum effect. Thus, 1 μm GW6471 was used in subsequent experiments. GW6471 (1 μm) had no effect on the frequency at which 30 mm KCl evoked a Ca2+ transient in neurons in the control condition (63%; n = 38; p = 0.1, Fisher's exact test).

Figure 3.

The PPARα antagonist increased the evoked Ca2+ transient in the small DRG neurons in the control condition. A, Pretreatment with GW6471 increased the amplitude of the Ca2+ transient in a concentration-dependent manner in small DRG neurons maintained in the control condition. The label of the y-axis is the same for B and C. B, Examples of Ca2+ transients evoked in small neurons maintained in the control condition during superfusion with vehicle (gray) or 1 μm GW6471 (black). The arrow indicates the time of superfusion with 30 mm KCl. Calibration: 30 s. C, Cotreatment with the PPARα agonist GW7647 blocked the effect of GW6471 on the amplitude of the Ca2+ transient. Results are reported as the median and the 25th to 75th percentile range; the numbers in the parentheses indicate the number of neurons with a positive response to 30 mm KCl. *Different at p < 0.05 (Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA on ranks followed by Dunn's test).

To determine whether the effect of GW6471 on the Ca2+ transient was mediated through PPARα, neurons were superfused with GW6471 (1 μm) in the presence of the synthetic agonist GW7647 (30 nm). Inclusion of GW7647 blocked the effect of GW6471 on the amplitude of the Ca2+ transient (H = 19.2, 3 df, p < 0.001; Kruskal–Wallis, one-way ANOVA on ranks followed by Dunn's test) (Fig. 3C). GW7647 (30 nm) alone had no effect on the amplitude of the Ca2+ transient compared with vehicle. None of the drugs had an effect on the basal [Ca2+]i compared with the vehicle (H = 3.1, 4 df, p = 0.54, Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA on ranks). For example, the median [Ca2+]i during superfusion with GW6471 (1 μm) was 84 nm (n = 39). These data indicate that the enhancement of the amplitude of evoked Ca2+ transient by GW6471 was mediated through PPARα. Moreover, the absence of an effect of pretreatment with PPARα agonists alone supports the conclusion that the ambient level of PEA or other endogenous ligand saturates PPARα in the control condition.

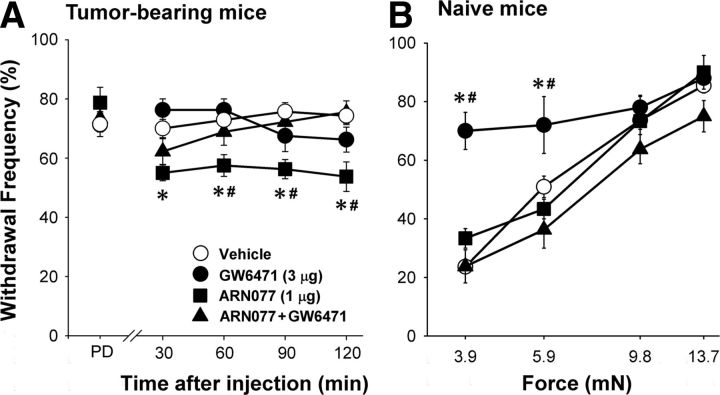

Effects of PPARα ligands on mechanical sensitivity in vivo paralleled their effects in vitro

The effects of drugs on mechanical hyperalgesia in tumor-bearing mice parallel their effects on the amplitude of the depolarization-evoked Ca2+ transient. Tumor-bearing mice exhibited mechanical hyperalgesia, defined by a withdrawal frequency of 70–80% in response to the 3.9 mN force, before drug treatment. Intraplantar injection of the NAAA inhibitor ARN077 (1 μg) ipsilateral to the tumor decreased mechanical hyperalgesia from 0.5 to 2 h after drug injection (F(12,159) = 2.95, p = 001, two-way ANOVA) (Fig. 4A). Recovery of mechanical hyperalgesia to the predrug level was evident 24 h after drug injection (withdrawal frequency of 72.5 ± 2.5%; n = 4; p = 0.76, paired t test). No change in mechanical sensitivity occurred in the paw contralateral to the drug injection (n = 8; p = 0.52, paired t test), indicating that the antihyperalgesic effect of ARN077 was mediated locally. The effect of ARN077 was blocked by coinjection of the PPARα antagonist GW6471 (3 μg, intraplantar). These data support the conclusion that the antihyperalgesic effect of NAAA inhibition of NAAA was mediated by an endogenous agonist of PPARα.

Figure 4.

The NAAA inhibitor and the PPARα antagonist had differential effects on mechanical sensitivity in tumor-bearing and naive mice. A, Mechanical hyperalgesia occurred in tumor-bearing mice before drug injection [predrug (PD)]. The NAAA inhibitor ARN077 (1 μg, intraplantar, ipsilateral to the tumor) decreased mechanical hyperalgesia, and its effect was blocked by coadministration of the PPARα antagonist GW6471 (3 μg, intraplantar). n = 4–9 mice/treatment. B, In naive mice, mechanical hyperalgesia was measured ipsilateral to intraplantar injection of the PPARα antagonist GW6471 (3 μg) at 1 h after drug injection. The mechanical hyperalgesia was blocked by coinjection of GW6471 with ARN077 (1 μg). The label for the y-axis is the same as for A. Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM. n = 3–11 mice/treatment. *Significantly different from vehicle and #different from GW6471 plus ARN077 at p < 0.02 (two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's t test).

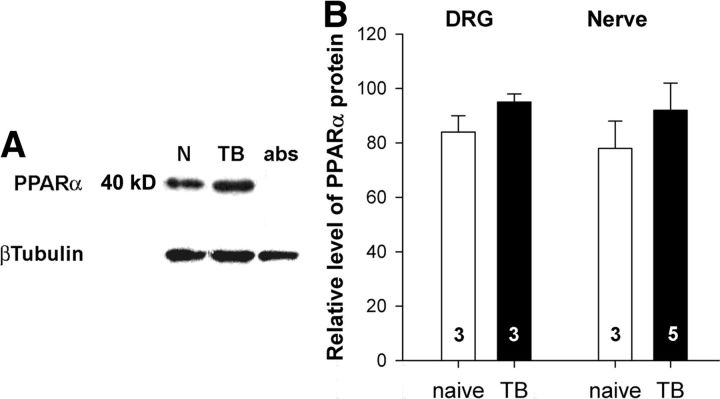

Conversely, in naive mice, ARN077 (1 μg, intraplantar) had no effect on the mechanical sensitivity of the hindpaw ipsilateral to the injection (Fig. 4B). However, mechanical sensitivity was increased by intraplantar injection of the PPARα antagonist GW6471 (3 μg) (F(9,107) = 3.4, p = 0.001 for interaction between mechanical forces and treatments, two-way ANOVA). Specifically, naive mice showed increased responses to monofilaments that delivered forces of 3.9 and 5.9 mN at 1 h after drug injection (p < 0.02, Bonferroni's t test). Recovery to baseline sensitivity was noted 24 h after injection of GW6471 when the withdrawal frequency to the 3.9 mN monofilament was 22 ± 2% (p = 0.69 compared with the predrug response, one-way ANOVA; n = 5). Importantly, the effect of GW6471 was blocked by cotreatment with ARN077 (1 μg, intraplantar), the inhibitor of PEA hydrolysis. The antagonist did not alter mechanical sensitivity in the paw contralateral to the injection (F(3,47) = 1.42, p = 0.25 for an interaction between mechanical forces and treatments of vehicle and GW6471, two-way ANOVA; n = 5–7 mice/treatment). The effect of tumors on the expression of PPARα in DRGs was estimated using quantitative RT-PCR and Western blots. The amount of PPARα mRNA tended to be higher in DRGs L3–L5 of tumor-bearing mice [ΔC(t) naive: 0.000 ± 0.361, n = 9; tumor-bearing: 0.750 ± 0.180, n = 9, p = 0.08, Student's t test]. Western blot analysis showed a PPARα-immunoreactive band at ∼40 kDa that was absorbed by preincubation of the diluted antibody with PPARα protein (Fig. 5A). Compared with samples from naive mice, there was no difference in tumor-bearing mice in the amount of PPARα-immunoreactive protein in this band in either DRGs or tibial nerve (p = 0.16 for DRGs and p = 0.38 for nerve, Student's t test) (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

The tumor condition did not change the expression of PPARα protein in DRGs or tibial nerve. A, Representative images of PPARα- and β-Tubulin-immunoreactive bands from a Western blot prepared of tibial nerves from naive (N) and tumor-bearing (TB) mice. B, Quantification of PPARα protein in DRGs and tibial nerves from naive and TB mice. The optical density of PPARα band was divided by the optical density of β-tubulin band and multiplied by 100. Data represent the mean ± SEM. The numbers inside the bars represent the sample size.

Discussion

Tumor-evoked pain may arise from multiple sources: factors released from tumor cells and immune cells as well as nerve injury. Our data provide the first evidence that the level of PEA in DRG cells decreases in response to coculture with fibrosarcoma cells in vitro and to the tumor they generate in vivo. The change is associated with decreased fatty acid ethanolamide signaling at PPARα in small DRG neurons and mechanical hyperalgesia in tumor-bearing mice. In the control condition, exogenous PPARα agonists had no effect on the depolarization-evoked Ca2+ transient. However, the Ca2+ transient evoked by a submaximal stimulus occurs more frequently in neurons from tumor-bearing mice and is larger in amplitude compared with neurons from naive mice (Khasabova et al., 2007). These changes were mimicked in the coculture condition. Increasing PEA in DRG neurons normalized the change in the Ca2+ transient in the cancer condition by decreasing the amplitude of the evoked transient through a PPARα-dependent mechanism. Evidence that local inhibition of NAAA, an enzyme that hydrolyzes PEA, reduced mechanical hyperalgesia in tumor-bearing mice through a PPARα-dependent pathway and local administration of a PPARα antagonist caused hyperalgesia in naive mice support the conclusion that PPARα signaling in nociceptors contributes to cellular mechanisms that set the threshold for nociception.

DRG neurons express NAAA

Several lines of evidence support the conclusion that DRG neurons express NAAA. First, NAAA mRNA was measured in DRGs of naive and tumor-bearing mice. Second, 15% of the hydrolysis of [3H]PEA by DRGs cocultured with fibrosarcoma cells was inhibited by ARN077, a potent and selective NAAA inhibitor (Armirotti et al., 2012). Finally, treatment with the NAAA inhibitor mimicked the effect of exogenous PEA on the depolarization-evoked Ca2+ transient in single DRG neurons.

Whether an increase in NAAA activity contributes to the reduced level of PEA in DRGs from tumor-bearing mice and the coculture condition is not clear. Although the level of NAAA mRNA in DRGs did not change in tumor-bearing mice, the data for [3H]PEA hydrolysis do not exclude a change in enzyme activity. The data for PEA hydrolysis were generated at a pH of 7.4, and a more accurate quantification of NAAA enzyme activity would occur at its optimal pH of 5 (Ueda et al., 2001). Because FAAH activity in DRGs increases in tumor-bearing mice (Khasabova et al., 2008), it most likely contributed to the increased [3H]PEA hydrolysis in the coculture condition. However, it is not likely that the reduced level of PEA in conditions of our experiments can be attributed to FAAH. Although PEA is a substrate for FAAH (Lichtman et al., 2002; Kathuria et al., 2003), the FAAH inhibitor URB597 (cyclohexylcarbamic acid 3'-carbamoyl-biphenyl-3-yl ester) does not alter the level of endogenous PEA in DRG cells under the same conditions that produce more than a twofold increase in AEA (Khasabova et al., 2012). These data suggest that endogenous PEA is localized to a cellular compartment that protects it from FAAH. Alternatively, a decrease in the capacity to generate fatty acid ethanolamides may contribute to the lower levels observed in DRGs in the cancer condition. Importantly, evidence that the coculture model mirrored the change in cellular PEA observed in vivo supports the utility of the model in studying the role of PEA and other substrates of NAAA in the function of DRG neurons.

The effect of PEA on DRG neurons was mediated by PPARα

Our conclusion that the effect of PEA on the depolarization-evoked Ca2+ transient is mediated by PPARα is supported by evidence that its effect was mimicked by a synthetic PPARα agonist and blocked by a PPARα antagonist. The selectivity of the drugs for PPARα is supported by evidence that each was effective at a concentration near its EC50 or IC50 at PPARα. PEA has an EC50 of 3 μm (LoVerme et al., 2005) and GW7647 has an EC50 of 6 nm (Brown et al., 2001) at the human PPARα. The IC50 of the antagonist GW6471 is 0.24 μm (Xu et al., 2002). Moreover, at these concentrations, the effect of each agonist was blocked by the antagonist when DRG neurons were prepared in the coculture condition, and the converse occurred in the control condition.

Inhibition of NAAA increased the level of PEA in DRG cells and mimicked the effect of PEA and PPARα agonists. In addition, the effect of the NAAA inhibitor on the Ca2+ transient was blocked by the PPARα antagonist. These data validate the physiological relevance of PEA as an agonist at PPARα in DRG neurons. Although AEA is also a substrate for NAAA (Sun et al., 2005), inhibition of NAAA did not result in increased AEA under the conditions tested. However, it is likely that other endogenous fatty acid ethanolamides that activate PPARα, such as oleoylethanolamide (Fu et al., 2003), were elevated following inhibition of NAAA and contributed to the observed effect.

Physiological implications

The effect of PPARα ligands on mechanical hyperalgesia in tumor-bearing mice was consistent with the effect of PPARα agonists on isolated DRG neurons in the coculture condition, thereby providing a meaningful physiological context for the effect of PPARα signaling on the depolarization-evoked Ca2+ transient. The inhibitory effect of the NAAA inhibitor on mechanical hyperalgesia in tumor-bearing mice is consistent with the effects of PPARα agonists in other models of hyperalgesia (Calignano et al., 2001; LoVerme et al., 2006; Sagar et al., 2008). However, the specific factors underlying the change in PPARα signaling in the cancer condition remain to be resolved. The acute mechanical hyperalgesia produced by the PPARα antagonist in naive mice is consistent with a recent report of thermal hyperalgesia in PPARα−/− mice (Ruiz-Medina et al., 2012) and supports the conclusion that activity of PPARα contributes to defining the threshold for activation of nociceptors. The lack of effect of PPARα agonists in naive mice and control cultures suggests that PPARα is saturated under normal conditions. Thus, the decrease in the level of PEA is likely one factor contributing to the change in PPARα signaling. Measures of PPARα mRNA and protein did not support a change in expression of PPARα in DRGs of tumor-bearing mice, but the sample size was small. A decrease in PPARα protein was noted in DRGs ipsilateral to an inflamed hindpaw (D'Agostino et al., 2009). Given that PPARα protein has a half-life of 1 h and ligand binding reduces its turnover (Blanquart et al., 2002), the benefit of inhibition of NAAA in tumor-bearing mice may be that an increase in endogenous PPARα ligands stabilizes the receptor and promotes its downstream effects. The effect of PPARα ligands on the evoked-Ca2+ transient in DRG neurons occurred within minutes, indicating the underlying signaling pathway is independent of gene transcription.

Mechanical hyperalgesia in tumor-bearing mice was associated with increased amplitude of the evoked Ca2+ transient in small DRG neurons. Calcium is an intracellular messenger that can promote hyperalgesia through multiple mechanisms including increased neurotransmitter release, gene expression, and membrane excitability (Berridge et al., 2000). The amplitude of a depolarization-evoked Ca2+ transient in neurons is an integration of Ca2+influx, efflux, and release from intracellular stores (Thayer and Miller 1990). The mechanism underlying the PPARα modulation of the Ca2+ transient remains to be resolved. The magnitude of the effect of PPARα agonists in the coculture condition suggests that PPARα most likely inhibits Ca2+ influx through voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels. Evidence that clearance of intracellular Ca2+ loads by a plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase and sarcoendoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase can be increased through an intracellular signaling pathway (Usachev et al., 2006) suggests these proteins may be other downstream targets. Overall, a drug-induced decrease in the amplitude of the Ca2+ transient in tumor-bearing mice would decrease hyperalgesia.

Because AEA, another fatty acid ethanolamide, is decreased in DRGs in the cancer condition, it is of interest to compare effects of PEA and AEA in parallel experiments. Similar to PEA, AEA decreases the amplitude of the evoked Ca2+ transient in small DRG neurons and mechanical hyperalgesia in tumor-bearing mice (Khasabova et al., 2008). These actions of AEA are mediated by CB1R coupling to inhibition of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels (Ross et al., 2001; Khasabova et al., 2004, 2008). However, the absence of an effect of PPARα on the occurrence of an evoked Ca2+ transient differs from CB1R activity in small DRG neurons. Anandamide decreases the occurrence of the Ca2+ transient evoked under conditions similar to those used in the present experiments (Khasabova et al., 2008), suggesting a divergence in PPARα and CB1 receptor signaling. A difference in underlying mechanisms most likely contributes to the positive interaction of AEA and GW7647 in promoting antinociception in the formalin assay (Russo et al., 2007).

Conclusion

Medium conditioned by fibrosarcoma cells decreased the levels of PEA and AEA in DRG neurons. The present data in conjunction with an earlier report (Khasabova et al., 2008) support the conclusion that consequences of these changes are decreased activation of PPARα by PEA and CB1R by AEA. Downstream effects of these receptors converge on decreasing the depolarization-evoked increase in [Ca2+]i. Thus, when levels of AEA and PEA decrease in DRG neurons, the amplitude of a depolarization-evoked Ca2+ transient increases, resulting in an increase in the activity of intracellular pathways to enhance nociception. Regardless of whether CB1R and PPARα are on the same neurons or different populations of neurons, the antihyperalgesic efficacy of FAAH inhibitors, which increase the level of AEA, is likely to be enhanced by NAAA inhibitors, which increase the level of PEA, in the management of cancer pain.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Cancer Institute Grant CA138684 (V.S.), National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant R01 DA012413 (D.P.), and the Undergraduate Research Opportunity Program of the University of Minnesota (Y.X.). We are grateful to P. Villalta and B. Mater at the University of Minnesota Cancer Center for assistance in the quantification of endocannabinoids and to N. Burlakova for technical assistance.

D.P. is lead inventor in a patent application on ARN077 filed by the University of California, Irvine, the Italian Institute of Technology, and the Universities of Parma and Urbino.

References

- Agarwal N, Pacher P, Tegeder I, Amaya F, Constantin CE, Brenner GJ, Rubino T, Michalski CW, Marsicano G, Monory K, Mackie K, Marian C, Batkai S, Parolaro D, Fischer MJ, Reeh P, Kunos G, Kress M, Lutz B, Woolf CJ, et al. Cannabinoids mediate analgesia largely via peripheral type I cannabinoid receptors in nociceptors. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:870–879. doi: 10.1038/nn1916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armirotti A, Romeo E, Ponzano S, Mengatto L, Dionisi M, Karacsonyi C, Bertozzi F, Garau G, Tarozzo G, Reggiani A, Bandiera T, Tarzia G, Mor M, Piomelli D. β-Lactones inhibit N-acylethanolamine acid amidase by S-acylation of the catalytic N-terminal cysteine. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2012;3:422–426. doi: 10.1021/ml300056y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge MJ, Lipp P, Bootman MD. The versatility and universality of calcium signaling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2000;1:11–21. doi: 10.1038/35036035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanquart C, Barbier O, Fruchart JC, Staels B, Glineur C. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARalpha) turnover by the ubiquitin-proteasome system controls the ligand-induced expression level of its target genes. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:37254–37259. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110598200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown PJ, Stuart LW, Hurley KP, Lewis MC, Winegar DA, Wilson JG, Wilkison WO, Ittoop OR, Willson TM. Identification of a subtype selective human PPARalpha agonist through parallel-array synthesis. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2001;11:1225–1227. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(01)00188-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadas H, Gaillet S, Beltramo M, Venance L, Piomelli D. Biosynthesis of an endogenous cannabinoid precursor in neurons and its control by calcium and cAMP. J Neurosci. 1996;16:3934–3942. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-12-03934.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadas H, di Tomaso E, Piomelli D. Occurrence and biosynthesis of endogenous cannabinoid precursor, N-arachidonoyl phosphatidylethanolamine, in rat brain. J Neurosci. 1997;17:1226–1242. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-04-01226.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calignano A, La Rana G, Giuffrida A, Piomelli D. Control of pain initiation by endogenous cannabinoids. Nature. 1998;394:277–281. doi: 10.1038/28393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calignano A, La Rana G, Piomelli D. Antinociceptive activity of the endogenous fatty acid amide, palmitylethanolamide. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;419:191–198. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)00988-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chizhmakov I, Mamenko N, Volkova T, Khasabova I, Simone DA, Krishtal O. P2X receptors in sensory neurons co-cultured with cancer cells exhibit a decrease in opioid sensitivity. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;29:76–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06556.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Agostino G, La Rana G, Russo R, Sasso O, Iacono A, Esposito E, Mattace Raso G, Cuzzocrea S, Loverme J, Piomelli D, Meli R, Calignano A. Central administration of palmitoylethanolamide reduces hyperalgesia in mice via inhibition of NF-kappaB nuclear signalling in dorsal root ganglia. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;613:54–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu J, Gaetani S, Oveisi F, Lo Verme J, Serrano A, Rodríguez De Fonseca F, Rosengarth A, Luecke H, Di Giacomo B, Tarzia G, Piomelli D. Oleylethanolamide regulates feeding and body weight through activation of the nuclear receptor PPAR-alpha. Nature. 2003;425:90–93. doi: 10.1038/nature01921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiura A, Sakamoto Y. Quantitative estimation of the effects of capsaicin on the mouse primary sensory neurons. Neurosci Lett. 1987;76:101–106. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(87)90200-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honore P, Rogers SD, Schwei MJ, Salak-Johnson JL, Luger NM, Sabino MC, Clohisy DR, Mantyh PW. Murine models of inflammatory, neuropathic and cancer pain each generates a unique set of neurochemical changes in the spinal cord and sensory neurons. Neuroscience. 2000;98:585–598. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00110-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsson SO, Fowler CJ. Characterization of palmitoylethanolamide transport in mouse Neuro-2a neuroblastoma and rat RBL-2H3 basophilic leukaemia cells: comparison with anandamide. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;132:1743–1754. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph EK, Parada CA, Levine JD. Hyperalgesic priming in the rat demonstrates marked sexual dimorphism. Pain. 2003;105:143–150. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(03)00175-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kathuria S, Gaetani S, Fegley D, Valiño F, Duranti A, Tontini A, Mor M, Tarzia G, La Rana G, Calignano A, Giustino A, Tattoli M, Palmery M, Cuomo V, Piomelli D. Modulation of anxiety through blockade of anandamide hydrolysis. Nat Med. 2003;9:76–81. doi: 10.1038/nm803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khasabova IA, Harding-Rose C, Simone DA, Seybold VS. Differential effects of CB1 and opioid agonists on two populations of adult rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. J Neurosci. 2004;24:1744–1753. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4298-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khasabova IA, Stucky CL, Harding-Rose C, Eikmeier L, Beitz AJ, Coicou LG, Hanson AE, Simone DA, Seybold VS. Chemical interactions between fibrosarcoma cancer cells and sensory neurons contribute to cancer pain. J Neurosci. 2007;27:10289–10298. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2851-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khasabova IA, Khasabov SG, Harding-Rose C, Coicou LG, Seybold BA, Lindberg AE, Steevens CD, Simone DA, Seybold VS. A decrease in anandamide signaling contributes to the maintenance of cutaneous mechanical hyperalgesia in a model of bone cancer pain. J Neurosci. 2008;28:11141–11152. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2847-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khasabova IA, Chandiramani A, Harding-Rose C, Simone DA, Seybold VS. Increasing 2-arachidonoyl glycerol signaling in the periphery attenuates mechanical hyperalgesia in a model of bone cancer pain. Pharmacol Res. 2011;64:60–67. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khasabova IA, Khasabov S, Paz J, Harding-Rose C, Simone DA, Seybold VS. Cannabinoid type-1 receptor reduces pain and neurotoxicity produced by chemotherapy. J Neurosci. 2012;32:7091–7101. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0403-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtman AH, Hawkins EG, Griffin G, Cravatt BF. Pharmacological activity of fatty acid amides is regulated, but not mediated, by fatty acid amide hydrolase in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;302:73–79. doi: 10.1124/jpet.302.1.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LoVerme J, Fu J, Astarita G, La Rana G, Russo R, Calignano A, Piomelli D. The nuclear receptor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α mediates the anti-inflammatory actions of palmitoylethanolamide. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;67:15–19. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.006353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LoVerme J, Russo R, La Rana G, Fu J, Farthing J, Mattace-Raso G, Meli R, Hohmann A, Calignano A, Piomelli D. Rapid broad-spectrum analgesia through activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;319:1051–1061. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.111385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meuser T, Pietruck C, Radbruch L, Stute P, Lehmann KA, Grond S. Symptoms during cancer pain treatment following WHO guidelines: a longitudinal follow-up study of symptom prevalence, severity and etiology. Pain. 2001;93:247–257. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00324-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Sullivan SE, Kendall DA. Cannabinoid activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors: potential for modulation of inflammatory disease. Immunobiology. 2010;215:611–616. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce RJ, Duchen MR. Differential expression of membrane conductances in dissociated mouse primary sensory neurons. Neuroscience. 1994;63:1041–1056. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90571-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross RA, Coutts AA, McFarlane SM, Anavi-Goffer S, Irving AJ, Pertwee RG, MacEwan DJ, Scott RH. Actions of cannabinoid receptor ligands on rat cultured sensory neurones: implications for antinociception. Neuropharmacology. 2001;40:221–232. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(00)00135-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Medina J, Flores JA, Tasset I, Tunez I, Valverde O, Fernandez-Espejo E. Alteration of neuropathic and visceral pain in female C57BL/6J mice lacking the PPAR-α gene. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2012;222:477–488. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2662-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo R, LoVerme J, La Rana G, D'Agostino G, Sasso O, Calignano A, Piomelli D. Synergistic antinociception by the cannabinoid receptor agonist anandamide and the PPAR-alpha receptor agonist GW7647. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;566:117–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagar DR, Kendall DA, Chapman V. Inhibition of fatty acid amide hydrolase produces PPAR-alpha-mediated analgesia in a rat model of inflammatory pain. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;155:1297–1306. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweizerhof M, Stösser S, Kurejova M, Njoo C, Gangadharan V, Agarwal N, Schmelz M, Bali KK, Michalski CW, Brugger S, Dickenson A, Simone DA, Kuner R. Hematopoietic colony-stimulating factors mediate tumor-nerve interactions and bone cancer pain. Nat Med. 2009;15:802–807. doi: 10.1038/nm.1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun YX, Tsuboi K, Okamoto Y, Tonai T, Murakami M, Kudo I, Ueda N. Biosynthesis of anandamide and N-palmitoylethanolamine by sequential actions of phospholipase A2 and lysophospholipase D. Biochem J. 2004;380:749–756. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thayer SA, Miller RJ. Regulation of the intracellular free calcium concentration in single rat dorsal root ganglion neurones in vitro. J Physiol. 1990;425:85–115. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuboi K, Hilligsmann C, Vandevoorde S, Lambert DM, Ueda N. N-Cyclohexanecarbonylpentadecylamine: a selective inhibitor of the acid amidase hydrolysing N-acylethanolamines, as a tool to distinguish acid amidase from fatty acid amide hydrolase. Biochem J. 2004;379:99–106. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda N, Yamanaka K, Yamamoto S. Purification and characterization of an acid amidase selective for N-palmitoylethanolamine, a putative endogenous anti-inflammatory substance. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:35552–35557. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106261200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usachev YM, Marsh AJ, Johanns TM, Lemke MM, Thayer SA. Activation of protein kinase C in sensory neurons accelerates Ca2+ uptake into the endoplasmic reticulum. J Neurosci. 2006;26:311–318. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2920-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wacnik PW, Eikmeier LJ, Ruggles TR, Ramnaraine ML, Walcheck BK, Beitz AJ, Wilcox GL. Functional interactions between tumor and peripheral nerve: morphology, algogen identification, and behavioral characterization of a new murine model of cancer pain. J Neurosci. 2001;21:9355–9366. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-23-09355.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu HE, Stanley TB, Montana VG, Lambert MH, Shearer BG, Cobb JE, McKee DD, Galardi CM, Plunket KD, Nolte RT, Parks DJ, Moore JT, Kliewer SA, Willson TM, Stimmel JB. Structural basis for antagonist-mediated recruitment of nuclear co-repressors by PPARα. Nature. 2002;415:813–817. doi: 10.1038/415813a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]