Abstract

Observational studies have examined the prevalence and impact of internalized stigma among African American women living with HIV, but there are no intervention studies investigating stigma reduction strategies in this population. Based on qualitative data previously collected, we adapted the International Center for Research on Women's HIV Stigma Toolkit for a domestic population of African American women to be consistent with Corrigan's principles of strategic stigma change. We implemented the intervention, led by an African American woman living with HIV, as a workshop across two afternoons. The participants discussed issues “triggered” by videos produced specifically for this purpose, learned coping mechanisms from each other, and practiced them in role plays with each other. We pilot tested the intervention with two groups of women (total N=24), measuring change in internalized stigma with the Stigma Scale for Chronic Illness before and after workshop participation. Sixty-two percent of the participants self-reported acquiring HIV through heterosexual sexual contact, 17% through intravenous drug use, 4% in utero, and 13% did not know the route of transmission. The intervention was feasible, enthusiastically accepted by the women, and led to decreased stigma from the start of the workshop to the end (p=0.05) and 1 week after (p=0.07) the last session of workshop. Findings suggest the intervention warrants further investigation.

Introduction

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that HIV was the leading cause of death for African American women between the ages of 25 and 34.1 A growing body of research has shown that the stigma experienced by people living with HIV (PLWHA) undermines adherence to HIV antiretroviral medications.2–7 Many African Americans note that closely adhering to antiretroviral regimens unintentionally discloses their HIV status, and in order to avoid perceived stigmas that occur after disclosure of their status, they poorly adhere to medications and likely poorly engage in treatment as well.2,8 Adherence to antiretroviral medications is an important factor in reducing the morbidity and mortality of HIV,9 and thus, high mortality rates for African Americans with HIV can be linked to poor access to and utilization of treatment resources.10–13 Strong evidence exists that ties psychosocial issues (e.g., internalized stigma, depressive symptoms, concerns about disclosure) to poor adherence and service utilization, necessitating the development of research-validated psychosocial interventions for people with HIV.7,14,15 Taken together, this body of work suggests that interventions aimed at challenging stigma might help to reduce poor health outcomes for African Americans living with HIV.

Internalized stigma reduction programs

Public stigmas refer to negative attitudes held by members of the public, such as health care professionals, clergy, or employers, about people with devalued characteristics that result in stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination. Once public stigmas are enacted (personally experienced), they can be internalized by the stigmatized individual if the individual endorses the public stigmas.16 Internalized HIV stigma has been the target of few stigma reduction programs, in order to improve health outcomes. A recent review of the literature on HIV stigma reduction interventions found only one intervention trial that was focused on reducing stigma among people with HIV.17 Furthermore, investigators found no studies that were aimed at reducing internalized stigma. Our own online Web-based and PubMed searches for internalized stigma reduction programs identified only three formal programs (those with manuals or materials) in which people living with HIV were or could be the target audience for stigma reduction. We found that only one of these three studies published an evaluation of results.

The only internalized stigma reduction program we found in the published research literature was the Emotional Writing Disclosure intervention, which has been examined through pilot study.18,19 The intervention required participants to write about their thoughts and feelings about stressful events experienced. The act of writing the experience down was theorized to help participants put their experiences in a positive light. The study by Abel and colleagues19 showed that after participating in the Emotional Writing Disclosure intervention, participants' psychological distress decreased. However, the intervention would not be feasible for use with people with limited literacy skills, as it requires participants to have proficiency with written expression.

Another stigma reduction program that aims to reduce internalized or public stigma was developed by the National Minority AIDS Council,20 funded by the Health Resources and Services Administration, work with communities of color to reduce stigma through action planning. This program primarily runs through presentation of a series of slides in workshop-type formats, and uses information dissemination as its primary mechanism for change.

On the other hand, the HIV Stigma Toolkit, developed by the International Center for Research on Women (ICRW), the Academy for Educational Development, and the International AIDS Alliance,21 has been used primarily to reduce public stigma in global settings. Of particular note, the Toolkit has been adapted and used by HPTN 043 Project Accept for stigma reduction in posttest support services within a larger HIV testing prevention initiative.22 The toolkit contains several modules with exercises developed to provide people with HIV ways in which to cope with internalized HIV stigma. The toolkit works at the individual level and uses a group format to encourage social support and active learning. The intervention was developed with stakeholder participation, using participatory action research methods.

The Unity Workshop

Brown et al.23 conducted a review of stigma reduction programs and outlined necessary components of these programs, which include education, contact with affected persons, counseling approaches, and training in coping skills. The education component is necessary to counter misinformation that exists about people with HIV and define stigma; contact with affected persons is necessary to humanize the illness; counseling approaches provide a modality for implementation; and coping skills training is necessary to help teach people ways to navigate stigmatizing situations. Similarly, Corrigan24 has stated that contact is a fundamental aspect of stigma reduction interventions.

Of the three programs that potentially would address internalized stigma among people with HIV, the ICRW program had the most potential to capture these elements. Thus, our intervention was primarily based on the ICRW program, which had been used in countries throughout Africa and Asia. The materials needed to be adapted for the African American context, and so we conducted focus groups with African Americans living with HIV to obtain information on their experiences with stigma that they would like addressed in an intervention and their opinion of the ICRW exercises' potential to reduce stigma. Results from the focus groups have been detailed elsewhere.25 To broadly summarize, women described pressing issues of stigma reduction around family and dating that should be addressed in a group format, and men suggested that stigma be addressed through an internet based format. We chose to begin our work by developing an intervention with African American women living with HIV.

We selected content and adapted exercises based on focus group feedback from African American women living with HIV, who rank ordered exercises from the ICRW program in terms of preference.25 In addition, instead of using the program's scenarios depicted in words and drawings that were catered towards an African village context, we developed four “trigger videos” that would ultimately become embedded within exercises of the intervention. We developed these videos based on scenarios outlined in the ICRW program and on stories that women in the focus groups provided about their own experiences. Social Learning Theory tells us that people learn through observation, imitation, and modeling,26 and thus, we held the view that coping mechanisms might best be observed through video and then subsequently role played. We also observed from an International Training and Education Center for Health (I-TECH) intervention developed for stigma reduction among health care workers in the Caribbean that videos tended to stimulate discussion and engage participants in active learning.27 The format for the interventions is described in the methods section.

The present study

As described above, programs exist to reduce stigma, but there is a paucity of effectiveness evaluations of these programs. Thus, instead of developing another intervention to reduce stigma, we adapted an intervention that had promise for internalized stigma reduction for African American women living with HIV. The primary aim of the present study was to feasibility test and gather preliminary data on the effectiveness of our adapted intervention. Our hypothesis was that participation in the group would lead to a reduction in symptoms of internalized stigma for African American women living with HIV.

Methods

Recruitment

African Americans comprise approximately 20% of the numbers of people living with HIV in King County, Washington (a predominantly urban and suburban setting), they make up only 5% of the population there.28 However, we thought that the study would be worthwhile to conduct in King County, given the critical need for addressing psychosocial issues within a population of African American women living with HIV, as African American women are given HIV diagnoses at a nine times higher rate than white women in King County.29 Thus, we recruited women from an HIV clinic located in a publicly funded medical center in Seattle. We posted flyers in the clinic rooms, and a nurse in the clinic encouraged interested potential participants to call the study coordinator if they expressed interest in research study participation. Women were eligible for inclusion in the study if (1) they identified as having an African American racial/ethnic background (this excluded women who were African-born), (2) they were at least 18 years of age or over, and (3) seeking medical treatment from the HIV clinic within the medical center. The study was approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board.

Intervention procedures

We ran the intervention as a workshop that met for 4–5 h during 2 consecutive weekday afternoons. An African American woman living with HIV who worked as a peer advocate in a community based organization for women living with HIV served as the primary workshop facilitator. A masters' level social worker assisted with facilitation and with leading break-out group sessions. The principal investigator on the study, a licensed clinical psychologist, was also on hand in case the women experienced any extreme psychological distress.

We developed an intervention manual with detailed instructions on how to move through the exercises in the workshop. We began the workshops by discussing group expectations and establishing ground rules. We then asked the participants to discuss what stigma meant to them. The main portion of the workshop focused on discussions and exercises to help participants acquire new coping skills. These exercises covered (1) practicing relaxation and self-care, (2) sharing coping strategies from other group members, (3) viewing trigger videos and (4) discussing how to handle potentially stigmatizing situations with family, in the workplace, and in other settings, and (5) role playing ways to navigate these difficult situations.

We conducted several of the exercises in smaller break-out sessions with approximately five participants per small group. We did this to facilitate in-depth discussions of topics and encourage participation and discussion from quieter members of the group. While convened as a large group, some exercises used videos, which can be viewed from websites listed here or a physical DVD. “Sisters” (www.youtube.com/watch?v=VmghpcEb9kc&feature=related) is a scenario about an older sister who is overprotective of a younger sister living with HIV. The “Counseling” scenario (www.youtube.com/watch?v=xIwmiq7ppaI&feature=related) depicts a young woman telling her counselor about the discrimination she faces with her parents at home. The “Lunchroom” video depicts a scene (www.youtube.com/watch?v=tCfLExQOWyw&feature=related) in which coworkers gossip about a person living with HIV. Finally, we scripted a “First Date” scenario (www.youtube.com/watch?v=vWvXH5tUUhQ&feature=related) involving two people beginning a romantic relationship and living positively with HIV. The participants viewed the videos, and their verbal reactions to the videos were encouraged. In addition, a structured, in-depth discussion of key concepts (e.g., a brainstorm of proactive and assertive ways of coping with stigmatizing situations) followed. In one exercise that did not use video, the women formed a “web of string,” in which one group member tossed a ball of yarn to another group member after calling out a positive quality about herself. We then asked the women to generate names for the web that had been created and linked them together. The women called out, “peace,” “togetherness,” and finally, “unity.” Thus, we named the workshop the Unity Workshop, after the web that symbolized the empowerment that comes about through social support.

Assessment schedule and measures

Our primary outcome was internalized stigma, as measured by Stigma Scale for Chronic Illness (SSCI). The scale items have been validated in 24-item and 8-item versions for with people living with neurological disorders.30,31 The original scale contained two factors, with items measuring both internalized and enacted stigma. We conducted cognitive interviews to assist in modification of the scale to be more appropriate for African Americans living with HIV (unpublished data). The interviews suggested a revision that resulted in a 14-item scale, measuring internalized and enacted stigma, with a 5-point Likert response format (1=never to 5=always). The scale contains items such as “I felt embarrassed about my illness,” “Because of my illness, I felt emotionally distant from other people,” and “I avoided making new friends.” As part of the SSCI completion, participants were prompted to think of the last 24 hours as the recall period. The items referred to “my illness,” which was defined as HIV infection in the introductory remarks. A subsequent study demonstrated that the items demonstrated good psychometric properties with a sample of African Americans living with HIV. In the psychometric study, Cronbach α was 0.93 and as a measure of concurrent validity, the SSCI's correlation with another HIV Stigma scale was 0.76. We averaged items and then multiplied by the number of items to produce a prorated total score to account for missing items. This prorated total score was used as the primary variable of interest in the statistical analyses.

At baseline, participants completed the SSCI. They also provided information about their socio-demographic background, whether they were attending social support groups currently. Participants self -reported these responses as a pretest, given just prior to the start of the workshop. Two follow-up posttests were also given to participants, one immediately after the workshop exercises were completed and the other 1 week after the workshop was completed.

The first posttest included the SSCI and open ended questions in which participants could provide written feedback on their experience during the workshop. We decided to solicit written feedback instead of conducing in person, debriefing interviews in order to avoid responses that were influenced by social desirability. In other words, we chose this manner of obtaining feedback to be more objective, so that participants might feel freer in responding on paper rather than from study staff who had attachments to the outcome of the study. We asked the women 7 questions: (1) How did you like the stigma group you attended?, (2) Did you attend all sessions?, (3) Did you have any difficulty attending the sessions?, (4) Did you have any difficulty speaking out during the sessions?, (5) Did you feel the exercises were applicable to your situation? If yes, how?, (6) How could the exercises be more appropriate?, (7) Do you feel the group has the potential to reduce the stigma in your life? If so, how? Exactly 1 week after the workshop was conducted, participants returned to complete posttest stigma measure.

Data analysis

We pooled the data from the two workshops to conduct the analyses. We carefully recorded the numbers of people who were interested in participating in the intervention and attendance of participants. Once the self-reported data was collected, we examined means and standard deviations on variables of interest. Our inferential statistical analyses were driven by the design of the study (pretest–posttest without a control group), and as such, we conducted two paired t tests to examine change in stigma scores. In the first analysis, participants' baseline stigma scores was paired with the posttest taken immediately after the workshop was completed (day 2). In the second analysis, the participants' baseline stigma scores were paired with the posttest taken 1 week after completion of the workshop. We also obtained written feedback on the intervention. These responses were content analyzed32 and general findings summarized.

Results

Recruitment and feasibility

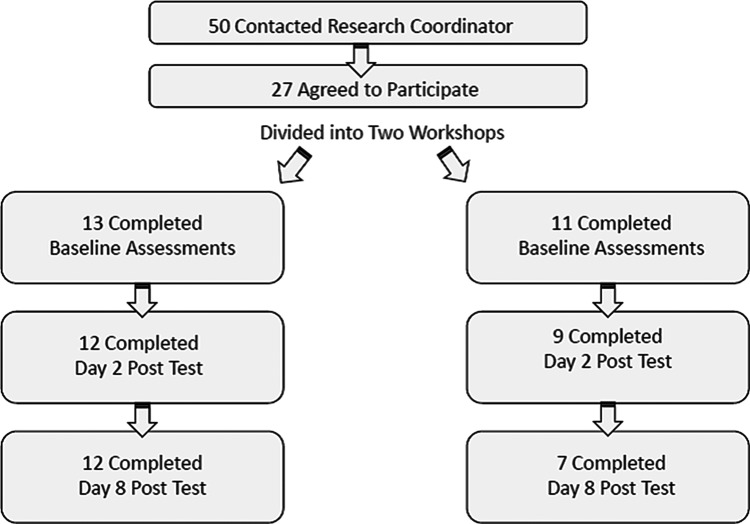

In all, 50 potential participants contacted the research study coordinator, who checked for eligibility and provided them with details of study procedures, location, and timing of the workshops. Twenty-seven potential participants were scheduled to participate in 1 of 2 workshops. The other 23 women declined to participate because they were unavailable (e.g., working, taking care of children) during the times offered for the workshops, which occurred during weekday afternoons. In all, 24 women attended the 2 workshops, 13 in the first workshop (92% attended the second session) and 11 in the second workshop (82% attended the second session). Three women did not attend the workshops. They were not officially study participants, and so we did not re-contact them to determine their reasons for not appearing. Figure 1 details the flow of participants from recruitment to participation. One of the participants who attended the first day only circled the same answer for all items. She stated that she had been experiencing vision difficulties during the afternoon, and thus her data were not included in the analysis.

FIG. 1.

Flow chart of recruitment and participation.

Our study coordinator contacted the women who did not attend day 2 of the workshop to inquire about reasons for not attending. Of the 5 participants who did not attend the follow-up, 1 participant stated she had no childcare options and thus needed to stay home to watch her grandchild, 1 participant stated that she was not feeling well, and 1 participant mentioned that she “got a job” and could not attend. Two other participants could not be reached.

Description of participants

Participants ranged in age from 20 to 59 years, and the average age of participants was 44 years (standard deviation [SD]=10 years). The women ranged in the number of children they had, from none to 8, and averaging 2 children (SD=2). The women also reported living with HIV from 3 months to 25 years. Detailed sociodemographic and clinical information is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and Clinical Profile of Participants

| Variable | Mean (SD) or frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | 44 (SD=10) years |

| Level of education | |

| Some high school | 9 (38%) |

| High school diploma/GED | 10 (42%) |

| Some college | 3 (12%) |

| Bachelor's degree | 2 (8%) |

| Marital status | |

| Never married | 13 (57%) |

| Married | 2 (9%) |

| Living with partner | 1 (4%) |

| Separated | 1 (4%) |

| Divorced | 6 (26%) |

| Number of children | 2 (SD=2) children |

| Living arrangement | |

| Alone | 10 (40%) |

| With other adults, no dependents | 6 (24%) |

| With other adults and dependents | 5 (20%) |

| With dependents only | 4 (16%) |

| Currently attending a support group | 11 (46%) |

| Likely mode of acquiring HIV infection | |

| Heterosexual sexual contact | 15 (62%) |

| Injection drug use | 4 (17%) |

| Mother to child | 1 (4%) |

| Unknown | 3 (13%) |

| Refuse to answer | 1 (4%) |

| AIDS diagnosis | 6 (25%) |

| Prescribed antiretroviral medication (N=21 respondents) | 16 (76%) |

| Taking antiretroviral medications (N=21 respondents) | 14 (68%) |

| CD4+ T cell counta | 573 (SD=193) |

Eleven participants reported they did not know their CD4+ T cell count. The number here represents the average count that 12 participants self-reported.

SD, standard deviation.

Intervention acceptability

There were no negative comments made when feedback on the workshop was elicited, and responses detailed the level of emotion in the room during the workshop and how personal differences gave way to a sense of unity and support. The women indicated that they felt empowered by the social support and lessons learned from others going through a similar experience. One woman stated, “I liked it a lot. I got to know more people and learned a lot about myself and stigma. The first day was emotional but the second I was much more open. Most of the situations I have personally dealt with. It made me open up and release issues I have been holding for the last 10 years, and talking with others, I don't feel so segregated.” Another participant said, “I enjoyed the stigma group very much. I was a little late but I had bus transportation problems. The location was great. I can be naturally shy, but when asked, I can usually speak out. Sometimes I don't relate to the women as much as I would like because I am very young and have a very unique background. It helped to speak out about status to other women more than anything.” In addition to this positive feedback, we observed that when videos ended, all the women spoke at once to express their reaction to the scenarios, demonstrating active learning. We also noticed women exchanging phone numbers to reconnect outside of the study, strengthening their social support networks.

Internalized stigma outcomes

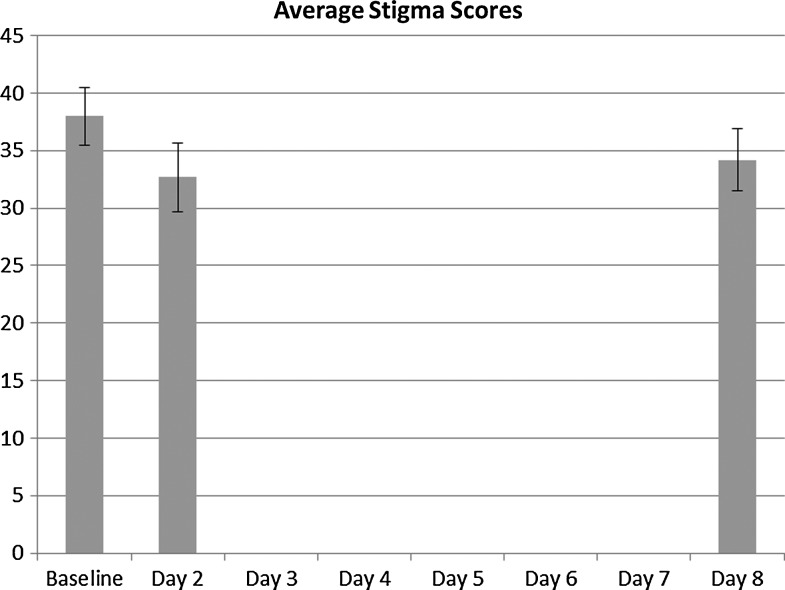

Overall, the 24 women's total stigma scores decreased from a mean of 38.0 (SD=11.4) at baseline/day 1 to a mean of 32.7 (SD=13.7) immediately after completion of exercises on day 2. In addition, from baseline to day 8, total stigma scores decreased from a mean of 38.0 (SD=11.4) at baseline/day 1 to a mean of 34.2 (SD=11.7). Figure 2 depicts the means in a bar chart. Paired t tests indicated statistical trends were present for changes in stigma scores from baseline to day 2 (t=2.1/df=20, p=0.054, confidence interval −0.1 to 10.8) and baseline to Day 8 (t=1.9/df=18, p=0.067, confidence interval −0.4 to 9.8). A paired t test also indicated that the increase in total stigma scores from day 2 to day 8 was not statistically significant (t=−0.3 /df=17, p=0.80, Confidence Interval −4.6 to 3.6).

FIG. 2.

Graphical depiction of stigma scores at baseline, day 2, and day 8.

Discussion

The results from this pilot study were encouraging. The recruitment of African American women living with HIV was feasible, in that once women attended day 1 of the workshop, the vast majority attended day 2 of the workshop to complete intervention exercises and study measures. These feasibility results suggested that the 2-afternoon workshop format was a practical method of retaining and engaging participants. In addition, the women's qualitative feedback revealed that the workshop content was highly acceptable. The women expressed that the intervention exercises and content help to empower them and foster social support. Finally, the process of piloting the intervention demonstrated that African American women living with HIV could learn skills to cope with HIV stigma from their peers, as well as through role playing exercises and discussions of scenarios modeled through video. Furthermore, the mean total stigma scores decreased after participation in the stigma reduction workshop. Although the study was not powered to determine efficacy, p values approached conventional levels of significance. Cohen's d was calculated to be 0.42, falling within a small to medium effect size as defined by Cohen.33

Our intervention used classic psychotherapeutic techniques such as role playing, modeling of behaviors through video, social support, and contact with peers. Contact with peers came in two forms. First, the women had contact with other African American women living with HIV, they shared methods of coping, and they learned coping skills from each other. Second, the workshop's moderator was an African American woman living with HIV and an experienced peer counselor. The workshop, with its emphasis on contact, fulfilled requirements necessary to fit Corrigan's model of Strategic Stigma Change: the workshops were targeted toward African American women, we worked with a community based organization and held focus group discussions to ensure that the workshop met local needs, and the workshops were grounded in real life stories from participants of focus group giving the content credibility.24 In fact, the content of the focus groups seemed relevant despite differences in the manner by which the women acquired HIV. One woman mentioned that she sometimes does not relate to others because “I am very young and have a very unique background,” but mentioned that it “helped to speak about status to other women more than anything.”

Although we had encouraging results, our study had limitations. First, our study lacked a control group. Second, the study included a relatively small sample of participants. Third, our design used a short follow-up period of one week. Fourth, although the program was literacy friendly, our outcome measures and open-ended feedback forms required participants to provide written responses and visual acuity, and thus our outcomes were not literacy or vision friendly. Future studies can correct some of these limitations. We have examined the use of audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI) in collecting individual responses about internalized stigma, which worked well with our sample. However, using ACASI in a group setting poses resource-related challenges (e.g., having touch screen computers available for all workshop participants to complete measures at the same time). In addition, these results point to the potential need for a “booster session” that could sustain reduction in stigma levels, and a future study could be designed to investigate the effect of such a session.

On the whole, the intervention was literacy friendly and did not require participants to be particularly literate to engage with other women in the group. In addition to this strength, our adaptation approach ensured its cultural appropriateness for African American women living with HIV, which likely related to the participants' positive feedback on the acceptability of the intervention content. Our next steps with the intervention will be to test its effectiveness in a large-scale, randomized controlled trial. Our team is planning a future study in other geographical regions of the United States that will help us collect data regional appropriateness for wide spread dissemination of the intervention. This future study will also measure stigma and correlates of morbidity (e.g., engagement in care, medication adherence, CD4+ T cell count) across 3 and 6 month periods of time. These results demonstrate the potential for the Unity Workshop to address stigma for African American women living with HIV, and the potential for stigma reduction using these tools both within the United States and internationally.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all of the participants of this study and the studies that led up to the development of this intervention. We would also like to thank Halley Brunsteter for her assistance in the final phases of the project and Cynthia Grossman for her support and encouragement during all phases of the study. This study was funded by a career development award from the National Institute of Mental Health (K23 MH 084551).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report: Cases of HIV infection and AIDS in the United States. 2004.

- 2.Rao D. Kekwaletswe TC. Hosek S. Martinez J. Rodriguez F. Stigma and social barriers to medication adherence with urban youth living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2007;19:28–33. doi: 10.1080/09540120600652303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rintamaki LS. Davis TC. Skripkauskas S. Bennett CL. Wolf MS. Social stigma concerns and HIV medication adherence. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2006;20:359–368. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ware NC. Wyatt MA. Tugenberg T. Social relationships, stigma and adherence to antiretroviral therapy for HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care. 2006;18:904–910. doi: 10.1080/09540120500330554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sayles J. Wong M. Kinsler J. Martins D. Cunningham W. The association of stigma with self-reported access to medical care and antiretroviral therapy adherence in persons living with HIV/AIDS. J Gen Intern Med. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1068-8. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rao D. Feldman B. Fredericksen R, et al. A structural equation model of HIV-related stigma, depressive symptoms, and medication adherence. AIDS Behav. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Blashill A. Perry N. Safren S. Mental health: A focus on stress, coping, and mental illness as it relates to treatment retention, adherence, and other health outcomes. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2011;8:215–222. doi: 10.1007/s11904-011-0089-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson J. Chesney M. Neilands T, et al. Disparities in reported reasons for not initiating or stopping antiretroviral treatment among a diverse sample of persons living with HIV. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:247–251. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0854-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chesney M. Ickovics J. Hecht FM. Sikipa G. Rabkin J. Adherence: A necessity for successful HIV combination therapy. AIDS. 1999;13(Suppl A):S271–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siegel K. Karus D. Schrimshaw EW. Racial differences in attitudes toward protease inhibitors among older HIV-infected men. AIDS Care. 2000;12:423–434. doi: 10.1080/09540120050123828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kahn JG. Zhang X. Cross LT. Palacio H. Birkhead GS. Morin SF. Access to and use of HIV antiretroviral therapy: variation by race/ethnicity in two public insurance programs in the U.S. Public Health Rep. 2002;117:252–262. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50159-0. ; discussion 231–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen M. Olszewski Y. Webber M, et al. Women identified with HIV at labor and delivery: Testing, disclosing, and liniking to care challenges. Maternal Child Health. (in press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Palacio H. Kahn JG. Richards TA. Morin SF. Effect of race and/or ethnicity in use of antiretrovirals and prophylaxis for opportunistic infection: A review of the literature. Public Health Rep. 2002;117:233–251. doi: 10.1093/phr/117.3.233. ; discussion 231–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martinez J. Harper G. Carleton RA. Hosek S. Bojan K. Glum G. Ellen J Adolescent Medicine Trials Network. The impact of stigma on medication adherence among HIV-positive adolescent and young adult females and the moderating effects of coping and satisfaction with health care. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2012;26:108–115. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.0178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Serovich JM. Craft SM. Reed SJ. Women's HIV disclosure to family and friends. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2012;26:241–249. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.0319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Corrigan P. Watson A. The paradox of self-stigma and mental illness. Clin Psychol. 2002;9:35–53. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sengupta S. Banks B. Jonas D. Miles M. Smith G. HIV interventions to reduce HIV/AIDS stigma: A systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2011;15:1075–1087. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9847-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abel E. Women with HIV and stigma. Fam Community Health. 2007;30(1 Suppl):S104–106. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200701001-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abel E. Rew L. Gortner E-M. Delville CL. Cognitive reorganization and stigmatization among persons with HIV. J Adv Nurs. 2004;47:510–525. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Minority AIDS Council. HIV/AIDS Stigma Program. Washington, D.C.: National Minority AIDS Council; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kidd R. Clay S. Chiiya C. Understanding and Challenging HIV/AIDS Stigma: A Toolkit for Action. International Center for Research on Women, Academy for Educational Development (AED), International AIDS Alliance; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khumalo-Sakutukwa G. Morin S. Kevany S. Project Accept Post Test Support Services (PTSS) 2010. CAPS HIV Prevention Conference. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Brown L. Macintyre K. Trujillo L. Interventions to reduce HIV/AIDS stigma: What have we learned? AIDS Educ Prev. 2003;15:49–69. doi: 10.1521/aeap.15.1.49.23844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Corrigan P. Best practices: Strategic stigma change (SSC): Five principles for social marketing campaigns to reduce stigma. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62:824–826. doi: 10.1176/ps.62.8.pss6208_0824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rao D. Singleton J. Lambert N. Cohn S. Stigma reduction: Experiences and Attitudes among Black Women Living with HIV. 39th American Public Health Association Annual Meeting; Washington, D.C.. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aronson E. Wilson T. Akert R. Social Psychology. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 27.HIV/AIDS Stigma and Discrimination in Caribbean Health Care Settings: Trigger Scenarios. Seattle, WA: International Training and Education Center for Health(I-TECH) and Caribbean HIV/AIDS Regional Training (CHART) Network; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Washington State Department of Health. HIV/AIDS Epidemiology Report. Seattle, WA: HIV/AIDS Epidemiology Unit, Washington State Department of Health; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Washington State Department of Health. Facts about HIV/AIDS in People of Color. Seattle, WA: Public Health Seattle King County; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Molina Y. Choi S. Cella D. Rao D. The Stigma Scale for Chronic Illnesses 8-item version (SSCI-8): Development, validation, and use across neurological conditions. Int J Behav Med. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Rao D. Choi S. Victorson D, et al. Measuring stigma across neurological conditions: The development of the Stigma Scale for Chronic Illness (SSCI) Qual Life Res. 2009;18:585–595. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9475-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miles M. Huberman A. Qualitative Data Analysis. 2nd. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112:1. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]