Abstract

Background

Transplant centers vary in the proportion of kidney transplants performed using live donors. Clinical innovations that facilitate live donation may drive this variation.

Methods

We assembled a cohort of renal transplant candidates at 194 US centers using registry data from 1999 – 2005. We measured magnitude of live donor transplant (LDKTx) through development of a standardized live donor transplant ratio (SLDTR) at each center that accounted for center population differences. We examined associations between center characteristics and the likelihood that individual transplant candidates underwent LDKTx. To identify practices through which centers increase LDKTx, we also examined center characteristics associated with consistently being in the upper three quartiles of SLDTR.

Results

The cohort comprised 148,168 patients, among whom 34,593 (23.3%) underwent LDKTx. In multivariable logistic regression, candidates had an increased likelihood of undergoing LDKTx at centers with greater use of “unrelated donors” (defined as non-spouses and non-first-degree family members of the recipient; OR 1.31 for highest versus lowest use, p=0.02) and at centers with programs to overcome donor-recipient incompatibility (OR 1.33, p=0.01.) Centers consistently in the upper three SLDTR quartiles were also more likely to use “unrelated” donors (OR 8.30 per tertile of higher use, p<0.01), to have incompatibility programs (OR 4.79, p<0.01), and to use laparoscopic nephrectomy (OR 2.53 per tertile of higher use, p=0.02).

Conclusion

Differences in center population do not fully account for differences in the use of LDKTx. To maximize opportunities for LDKTx, centers may accept more unrelated donors and adopt programs to overcome biological incompatibility.

Keywords: Live donor transplantation, center variation

Introduction

Compared to deceased donor kidney transplantation, live donor kidney transplantation (LDKTx) offers longer patient and allograft survival and greater opportunities for pre-emptive transplantation.(1-3) In the United States (US), the volume of live kidney donation more than doubled from 1994 – 2006, but has since declined.(4) During this growth period, multiple innovations took place, including laparoscopic nephrectomy, greater use of “unrelated” donors (who are not first degree family members or spouses of the recipient), and the development of methods to overcome biological incompatibility between donor-recipient pairs.(5-10) Assessment of variation in the magnitude of LDKTx between centers could be an important step toward identifying center practices that facilitate live kidney donation.

Centers vary widely in the proportion of kidney transplants performed using live donors, although a valid comparison of LDKTx rates would require adjustment for the demographics of the center’s population.(11) For instance, older age and black race are associated with a lower likelihood of LDKTx.(11-19) While centers cannot easily change the populations they serve, a center may facilitate LDKTx through innovative programs – such as recipient desensitization or living donor exchange.(5, 6, 20) These approaches are hypothesized to increase LDKTx overall, but their expense and time-demands may impede other important center work such as new donor evaluations. The effects of other practices (such as using unrelated donors) and other center attributes (such as volume) on LDKTx have not been fully explored.

The study had three aims. The first aim was to develop a standardized live donor transplantation ratio (SLDTR) that would assess center differences in LDKTx rates after adjustment for center population. The second and third aims were to identify center attributes associated with greater odds that an individual candidate would undergo LDKTx, and center attributes associated with greater odds that a center was consistently in the upper three quartiles of SLDTR.

Results

The primary cohort consisted of 148,168 individuals at 194 centers. 34,593 (23.3%) underwent LDKTx within 1.5 years; 39.3% of these recipients were never wait-listed. Among transplant candidates who were wait-listed and underwent LDKTx, the distribution of wait-list time was right-skewed, with a median of 162 days (about 5.4 months).

Table 1 presents characteristics of individuals who did and did not meet the outcome of LDKTx within 1.5 years. In unadjusted analyses, older age, black race, Hispanic ethnicity, diabetes, elevated panel reactive antibody (PRA), type O blood, lower education, and non-private health insurance were associated with a lower likelihood of LDKTx (p<0.05 for all variables). These characteristics were used to generate strata for indirect standardization, to calculate the expected number of live donor transplants at each center and to calculate each center’s SLDTR during each year. Because prior studies have suggested an association between LDKTx and sex, we also used sex for the indirect standardization.(21)

Table 1. Subject characteristic.

| Variable | Value |

LD tx within

1.5 years n=34593 |

No LD tx

within 1.5 years n=113575 |

p- value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at wait-listing | N | <.0001 | ||

| Mean +/- s.d. | 45.3 +/- 13.4 | 48.3 +/- 12.8 | ||

| Median | 46.0 | 49.0 | ||

| Range | 18.0 - 86.6 | 18.0 - 91.0 | ||

| Gender | Male | 20388 (58.9) | 66422 (58.5) | 0.1335 |

| Female | 14205 (41.1) | 47153 (41.5) | ||

| Race | White | 24002 (69.4) | 52136 (45.9) | <.0001 |

| Black | 4826 (14.0) | 35573 (31.3) | ||

| Hispanic | 4015 (11.6) | 16694 (14.7) | ||

| Asian | 1146 (3.3) | 6367 (5.6) | ||

| American Indian/Alaskan Native |

248 (0.7) | 1206 (1.1) | ||

| Other | 356 (1.0) | 1599 (1.4) | ||

| Cause of ESRD | Diabetes | 7572 (21.9) | 37791 (33.3) | <.0001 |

| Hypertension | 5200 (15.0) | 22760 (20.0) | ||

| Polycystic kidney disease | 3291 (9.5) | 6329 (5.6) | ||

| Glomerulonephritis | 3799 (11.0) | 8647 (7.6) | ||

| Congenital/reflux nephropathy | 1043 (3.0) | 1310 (1.2) | ||

| Other | 13688 (39.6) | 36738 (32.3) | ||

| Diabetes | Yes | 9787 (28.3) | 48156 (42.4) | <.0001 |

| No | 24806 (71.7) | 65419 (57.6) | ||

| Peak PRA | N | 18713 | 108822 | <.0001 |

| Mean +/- s.d. | 7.4 +/- 19.2 | 23.7 +/- 35.3 | ||

| Median | 0.0 | 2.0 | ||

| Range | 0.0 - 100.0 | 0.0 - 100.0 | ||

| High PRA | Yes | 498 (1.4) | 16991 (15.0) | <.0001 |

| No | 34095 (98.6) | 96584 (85.0) | ||

| Blood group | O | 15433 (44.6) | 59384 (52.3) | <.0001 |

| A | 13442 (38.9) | 33122 (29.2) | ||

| B | 4387 (12.7) | 17953 (15.8) | ||

| AB | 1331 (3.8) | 3116 (2.7) | ||

| Type of insurance | Private | 21724 (62.8) | 46717 (41.1) | <.0001 |

| Medicaid | 1619 (4.7) | 9390 (8.3) | ||

| Medicare | 10200 (29.5) | 53808 (47.4) | ||

| Other | 1050 (3.0) | 3660 (3.2) | ||

| Education | No college | 12774 (36.9) | 50623 (44.6) | <.0001 |

| Some college | 7269 (21.0) | 21869 (19.3) | ||

| College degree | 7666 (22.2) | 17166 (15.1) | ||

| Unknown | 6884 (19.9) | 23917 (21.1) | ||

| Time to live-donor transplant (days) |

Median | 162 | ||

| Range | 0 - 547 | |||

| 85th percentile | 356 | |||

| 95th percentile | 471 | |||

| Donor age | N | 34589 | ||

| Mean +/- s.d. | 40.3 +/- 10.9 | |||

| Median | 40.0 | |||

| Range | 15.0 - 79.0 | |||

| Donor gender | Male | 14370 (41.5) | ||

| Female | 20223 (58.5) | |||

| Donor race | White | 24502 (70.8) | ||

| Black | 4469 (12.9) | |||

| Hispanic | 4054 (11.7) | |||

| Asian | 1023 (3.0) | |||

| American Indian/Alaskan Native |

222 (0.6) | |||

| Other | 323 (0.9) | |||

| Relationship to recipient |

Biological: Blood-related parent |

2775 (8.0)a | ||

| Biological: Blood-related child | 6770 (19.6) | |||

| Biological: Blood-related identical twin |

70 (0.2) | |||

| Biological: Blood-related full sibling |

10886 (31.5) | |||

| Biological: Blood-related half sibling |

417 (1.2) | |||

| Biological: Blood-related other relative |

2452 (7.1) | |||

| Non-biological: Spouse | 4567 (13.2) | |||

| Non-biological: Life partner | 70 (0.2) | |||

| Non-biological, unrelated: Paired exchange |

104 (0.3) | |||

| Non-biological, unrelated: Anonymous donation |

159 (0.5) | |||

| Non-biological, unrelated, living/deceased donor exchange |

19 (0.1) | |||

| Non-biological, other unrelated direct donation |

6292 (18.2) | |||

| Donor blood group | O | 22431 (64.8) | ||

| A | 9247 (26.7) | |||

| B | 2614 (7.6) | |||

| AB | 301 (0.9) |

High peak PRA defined as ≥80%

Transplant center characteristics (Table 2)

Table 2. Characteristics of transplant centers over the seven year period of study.

| Number of kidney transplant centers | 194 |

| Volume category 1: Range of mean annual overall kidney transplants (n=65centers) * |

11.4 – 41.3 |

| Volume category 2: Range of mean annual overall kidney transplants (n=65 centers) * |

41.4 – 76.7 |

| Volume category 3: Range of mean annual overall kidney transplants (n=64 centers) * |

76.9 – 313.4 |

| Mean annual live donor kidney transplants | 25.5 +/- 23.9 |

| Range | 0.7 – 153.6 |

| Mean live donor transplants/all kidney transplants (%) | 34.7 +/- 13.4 |

| Range | 2.5 – 77.1 |

| Mean laparoscopic donor nephrectomies/all nephrectomies (%) | 23.3 +/- 15.3 |

| Range | 0 – 69.0 |

| Mean unrelated donors/all donors (%) ** | 8.6 +/- 4.7 |

| Range | 0 – 24.4 |

| Mean Herfindahl-Hirschman index (HHI) *** | 0.16 +/- 0.26 |

| Number of centers performing any donor exchange transplants (%) **** |

36 (18.6) |

| Number of centers performing any blood group incompatible transplants (%) |

74 (38.0) |

Calculated by dividing all US kidney transplant centers into 3 groups of approximately equal size

Live donors who were not parents, siblings, children or spouses were categorized as “unrelated”

The HHI is a measure of market competition. Categories were defined by prior published literature(34)

Donor exchange transplants were living donor kidney transplants in which a live donor provided a kidney to a recipient through an exchange, for example, with another living donor-recipient pair; these exchanges are usually performed due to biological incompatibility between a donor and his or her intended recipient.

The mean annual number of live donor kidney transplants at a center was 25.5 (range 0.7 – 153.6). The mean proportion of unrelated donors/all live donors was 8.6%. Eighty-four (43.3%) centers performed any transplants between incompatible donor-recipient pairs.

Multivariable analysis of individual and center characteristics associated with the outcome of undergoing LDKTx (Table 3)

Table 3. Associations between the outcome of an individual receiving a live donor kidney transplant and characteristics of transplant candidates and centers in multivariable logistic regression *.

| Individual Characteristics | OR | 95% Confidence interval | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Black race | 0.44 | (0.41, 0.57) | <0.01 |

| Male sex | 0.94 | (0.91, 0.97) | <0.01 |

| Black race*Male sex interaction |

0.74 | (0.68, 0.81) | <0.01 |

| Diabetes | 0.53 | (0.58, 0.57) | <0.01 |

| High PRA | 0.07 | (0.06, 0.08) | <0.01 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 0.97 | (0.89, 1.05) | 0.43 |

| Age | |||

| 18 – 40 years | Reference | ||

| 41-60 years | 0.66 | (0.64, 0.69) | <0.01 |

| > 60 years | 0.58 | (0.54, 0.63) | <0.01 |

| Type O blood | 0.73 | (0.71, 0.76) | <0.01 |

| Education | |||

| No college | Reference | ||

| Some college | 1.13 | (1.08, 1.18) | <0.01 |

| College degree | 1.29 | (1.23, 1.34) | <0.01 |

| Unknown | 1.05 | (0.97, 1.13) | 0.22 |

| Insurance | |||

| Private | Reference | ||

| Medicaid | 0.46 | (0.44, 0.50) | <0.01 |

| Medicare | 0.51 | (0.48, 0.53) | <0.01 |

| Other | 0.65 | (0.57, 0.74) | <0.01 |

| Center Characteristics | |||

| Lowest volume tertile | Reference | ||

| Intermediate volume tertile | 1.02 | (0.78, 1.34) | 0.89 |

| Highest volume tertile | 0.92 | (1.04, 1.64) | 0.54 |

| Use of donor exchange or ABO incompatible transplant |

1.33 | (1.06, 1.66) | 0.01 |

| Lowest tertile of unrelated donors |

Reference | ||

| Intermediate tertile of unrelated donors |

0.98 | (0.77, 1.24) | 0.86 |

| Highest tertile of unrelated donors |

1.31 | (1.04, 1.64) | 0.02 |

| Lowest tertile of laparoscopic nephrectomy |

Reference | ||

| Intermediate tertile of laparoscopic nephrectomy |

0.92 | (0.71, 1.20) | 0.54 |

| High tertile of laparoscopic nephrectomy |

0.93 | (0.73, 1.18) | 0.54 |

| Higher market competition | 1.15 | (0.92, 1.44) | 0.22 |

Empirical standard error estimates were used to determine confidence intervals

All individual characteristics associated with a lower likelihood of LDKTx in univariate analysis remained significant in multivariable logistic regression, except for Hispanic ethnicity. Notably, male sex was associated with a lower odds of LDKTx. A significant interaction between black race and male sex (OR 0.74, p<0.01) indicated that black men faced a particularly high barrier to finding a live donor.

Higher center use of unrelated donors (OR 1.31 for highest tertile versus lowest tertile of unrelated donors; p=0.02) and having a program to overcome donor-recipient incompatibility (OR 1.33; p=0.01) were associated with greater individual access to LDKTx.

Multivariable analysis of center characteristics and center ranking by magnitude of live donor kidney transplantation

The SLDTR had a mean of 1.1 (s.d. 0.5) and median of 1.0. During the seven years of the study, the mean SLDTR remained close to 1, but the upper bound of the SLDTR increased from 2.5 to 3.6.

One hundred forty-six centers (75.3%) were in the upper three SLDTR quartiles for at least four years. Centers in the highest three quartiles in any year were very likely to be in the highest three quartiles during another year. For example, compared to centers in the lowest quartile in 2003, centers in the highest three quartiles in 2003 had an odds ratio of 90.0 (p<0.01) for being in the highest three quartiles again during 2004, 2005, or both.

In multivariable logistic regression, centers with a program to overcome donor-recipient incompatibility (OR 4.79; p<0.01), with greater use of unrelated donors (OR 8.30 per higher tertile of unrelated donor use; p<0.01), and with greater use of laparoscopic nephrectomy (OR 2.53 per higher tertile of laparoscopic nephrectomy; p=0.02) were more likely to be in the upper three SLDTR quartiles for at least four years. Table 4 shows these results.

Table 4. Center characteristics associated with consistently ranking in the upper three quartiles of Standardized Live Donor Transplant Ratio from 2003 – 2005.

| Characteristic | OR | 95% Confidence interval | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Use of non-family donors, per higher tertile * |

8.30 | (3.71, 18.57) | <0.01 |

| Use of donor exchange or ABO incompatible transplant |

4.79 | (1.66, 13.79) | <0.01 |

| Use of laparoscopic nephrectomy, per higher tertile * |

2.53 | (1.19, 5.38) | 0.02 |

| Center volume of transplants, per higher tertile * |

1.39 | (0.77, 2.50) | 0.28 |

| Higher Market competition | 1.24 | (0.43, 3.61) | 0.70 |

ORs are not reported for each individual tertile, but rather for interval change between tertiles, because of insufficient sample size to add more variables to the model

Potential for expansion of live donor kidney transplantation

We estimated that an additional 766 transplants (mean 15.6 per low center) would take place if centers in the lowest quartile during 2005 performed the expected number of transplants.

Secondary analysis

In a linear regression model, we examined the secondary outcome of a center performing a higher proportion of (live donor transplants)/(all kidney transplants). Greater waiting time (β0.06 per tertile of higher waiting time; p<0.01), having a donor-recipient incompatibility program (β=0.06; p<0.01), using a higher proportion of unrelated donors (β=0.06 per tertile of unrelated donor use; p<0.01), and greater use of laparoscopic nephrectomy (β=0.03 per tertile of laparoscopic nephrectomy; p<0.01) were all associated with this outcome, while higher center volume was inversely associated with this outcome (β=-0.01; p=0.03).

Discussion

Our analysis revealed wide variation in the magnitude of LDKTx across centers after adjustment for their patient populations. Center use of unrelated live donors and the presence of a biological incompatibility program were associated with greater odds that an individual candidate would undergo LDKTx. Centers with greater use of unrelated donors, with a biological incompatibility program, and with greater use of laparoscopic nephrectomy were less likely to lag behind others in the magnitude of LDKTx. These findings may help guide centers toward practices that expand access to LDKTx.

Our study confirmed substantial disparities in access to LDKTx associated with black race and older age. The findings related to race may be due to the higher prevalence of kidney disease and poverty in this population, which could limit the number of medically suitable donors who can manage the financial burden of donation.(14, 22, 23) We hypothesize that older candidates feel protective of potential donors and discourage them. Potential donors may also sense that transplantation confers less benefit to older recipients.(12, 18)

Higher education and private insurance were associated with greater individual access to LDKTx. Education and health literacy may be important to recognizing the benefits of LDKTx. This finding underscores the need for transplant programs to provide information that is easily understood by individuals with limited literacy.(24, 25) It is also possible that private insurance is simply a marker for greater wealth, social status and support, and that patients with these means can attract live donors.

The SLDTR metric showed evidence of stability. We focused particular attention on the contrast between centers in the lowest quartile – where transplant candidates have minimal access to LDKTx – versus centers consistently in the upper three quartiles of SLDTR. Centers in the highest three quartiles were highly likely (OR 90.0) to remain in those quartiles the next year. This finding suggests that a center’s ranking was not usually due to random variation, but rather to modifiable processes of care.

Center practices may increase the magnitude of LDKTx. Our analysis confirms the importance of donor-exchange and blood-group incompatible transplant in expanding overall use of LDKTx.(5, 26) However, these programs are resource intensive. Desensitization of blood-group incompatible pairs (and of recipients with antibodies against donor human leukocyte antigens) also may heighten risks of infection and malignancy. On the other hand, the acceptance of unrelated donors is neither more risky nor ethically problematic than accepting related donors. Encouraging transplant centers to expand the use of unrelated donors could be an under-recognized way of maximizing LDKTx. We acknowledge that unmeasured center attributes are also likely to drive variation in LDKTx rates. Some centers may have staff with greater personal interest in working with live donors; other centers may devote greater resources to educational initiatives to raising awareness about the benefits of LDKTx. Interestingly, a metric of market competition (defined by donor service area) was unrelated to the SLDTR. It is possible that many centers actually compete beyond region and that the proximity of local centers has little effect on their practices with respect to LDKTx. It is also plausible that the financial benefits that centers gain from increasing live donor transplant drives their practice more than market competition.

Our study has limitations. First, the selection of live donors must respect their health and interests. Our group and others have voiced concern about accepting “medically complex live donors” – donors with risk factors for kidney disease such as obesity.(27-30) One troubling way that centers may increase LDKTx is through relaxing donor medical criteria. Due to missing relevant data, we were not able to examine how the use of medically complex donors may explain SLDTR variation.

We also used multiple imputation to account for missing data about PRA and the date of transplant readiness among live donors who were never wait-listed. Imputation may create bias, although sensitivity analyses suggest that imputation did not affect our main results.

We acknowledge the methodological limitation of excluding early recipients of deceased donor transplants from the SLDTR calculation. We developed this approach because the receipt of a deceased donor kidney within only 1.5 years of entering the wait-list would be considered a favorable outcome for almost any patient. Centers should not necessarily be “penalized” for not facilitating LDKTx for individuals who rapidly received deceased donor allografts. Removing these early deceased donor recipients allowed the analysis to focus on candidates with extended periods on the wait-list, during which patients often suffer deteriorating health. Also, our approach effectively allowed us to account for differences in waiting time and access to deceased donor allografts between regions. As Segev et al. have shown, patients and centers in regions with a short waiting time may be less likely to pursue LDKTx.(31) In the future, if further development of methods to compare LDKTx rates became a priority for the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), centers might be required to report the date of transplant readiness for all candidates; the SLDTR could then be calculated using a time-to-event approach in which deceased donor kidney recipients were censored at transplantation.

Our analysis also does not provide insight into events prior to “transplant readiness.” Some centers may be highly efficient at completing the donor workup, but our dataset did not allow us to study the effect of center practices on candidate outcomes prior to either wait-listing or actual transplantation. Lastly, our study did not measure the impact of educational programs about LDKTx for referring nephrologists, primary care doctors, or the general public; these efforts may also increase donation rates.

Conclusions

Variation in LDKTx across centers is only partly explained by differences in center populations and practices. Comparing rates of LDKTx provides an opportunity to identify those centers that do not maximize opportunities for candidates to receive a live donor transplant. In particular, developing programs such as live donor-exchange that overcome biological incompatibility, and increasing the acceptance of unrelated donors, may enable expansion of LDKTx.

Methods

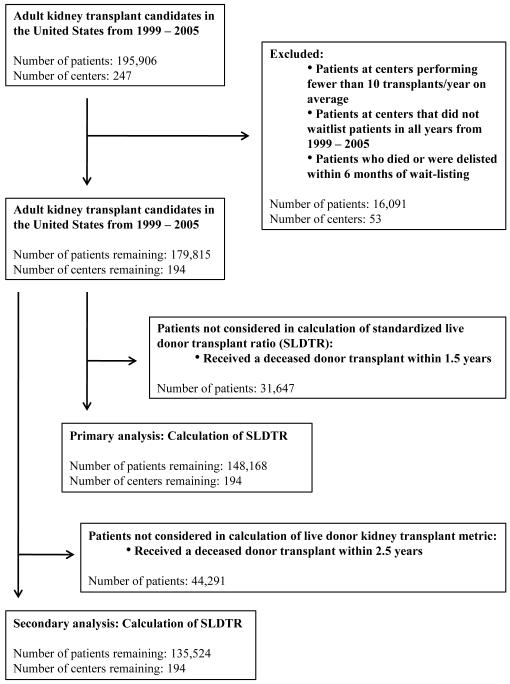

Generation of cohorts (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Generation of the study cohort

We used UNOS data to assemble 7 cohorts of adult (≥18 years) candidates considered eligible for LDKTx corresponding to the years 1999 - 2005. We defined a transplant candidate as any adult added to the kidney transplant wait-list during that year. Individuals who underwent LDKTx but were never added to the list were also considered candidates and were assigned a date of transplant readiness of 192 days prior to transplantation (the median days for recipients who were wait-listed).

Measurement of live donor kidney transplantation

To compare the LDKTx rate between centers, we analyzed live donor transplants within 1.5 years of the date of transplant readiness. This time period was selected because, among individuals who were wait-listed and underwent LDKTx, 85% of these transplants took place within 1.5 years.

Exclusion criteria

We excluded patients at centers that performed, on average, <10 kidney transplants per year and that did not add anyone to the wait-list during every year of the study period. To account for differences in severity of illness between center populations, we excluded patients who died or were removed from the wait-list within 6 months. To account for regional variation in the availability of deceased donor allografts, we removed any patient who underwent deceased donor kidney transplantation within 1.5 years of wait-listing. Removing deceased donor transplant recipients was consistent with our primary focus on patients who languish on the wait-list without access to transplantation.

Transplant candidate characteristics

On the basis of prior studies and our clinical experience, we examined associations between the outcome of an individual undergoing LDKTx and these characteristics: age, black race, Hispanic ethnicity, sex, diabetes, elevated PRA (a binary variable defined by UNOS convention as ≥80% or not), blood group (a binary variable defined as type O or not), education (defined as no college education, some college education, and completing college), and health insurance (private, Medicare, Medicaid, or other).(11, 13, 18, 21) Age was examined as an ordinal variable (<40, 40 – 60, >60 years) since the association with LDKTx was not linear.

Center characteristics

These center characteristics were evaluated: use of “unrelated” donors (the mean proportion of unrelated donors/all live donors); use of laparoscopic nephrectomy (the mean proportion of laparoscopic nephrectomies/all live donor nephrectomies); performing any LDKTx across incompatible blood groups; performing any donor exchanges; center volume of kidney transplants; and market concentration. Market concentration of transplant centers was assessed using the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI), (32) calculated as the sum of the squared market shares of centers in a donor service area.(32, 33) We converted the HHI into a binary variable using a traditional cut-point from economics (≤0.10 is high competition, >0.10 is low competition).(34, 35)

Because the variables of laparoscopic nephrectomy use, center volume, and proportion of non-family donors were skewed, we converted these variables to ordinal tertiles. Center practices of ABO-incompatible transplant and donor exchange were highly correlated (p<0.01), so we categorized centers performing either practice as having a biological incompatibility program.

Multivariable analysis for the outcome of an individual undergoing live donor kidney transplantation (Aim 1)

We fit a multivariable logistic regression model for the outcome of an individual undergoing LDKTx and entered independent center and patient characteristics. Given a study of access to kidney transplantation that showed an age-gender interaction, we explored for interactions between age and gender, age and race, and gender and race.(12)

Generation of an adjusted metric of center-specific rate of live donor kidney transplantation

Using the individual characteristics that were significantly associated with LDKTx in univariate analysis, we used indirect standardization to determine strata within the population of transplant candidates nationally.(36) Indirect standardization has been widely used to calculate expected rates of medical events such as deaths among dialysis patients.(37, 38) We applied stratum-specific rates of LDKTx to each center’s population to derive the expected number of live donor transplants per year. We then calculated the ratio of observed to expected transplants at that center (the SLDTR).

Multivariable analysis of center characteristics and the outcome of center ranking by magnitude of live donor kidney transplantation (Aim 2)

We ranked centers by SLDTR and divided them into quartiles each year. Centers were then categorized according to the binary outcome of whether or not the center had a consistently low magnitude of LDKTx, defined as being in the lowest SLDTR quartile for the majority of the study period (i.e., at least four out of seven years). We focused on identifying characteristics of centers that performed fewer live donor transplants, because these centers have the greatest opportunity to expand the practice. Also, centers repeatedly in the lowest quartile would be less likely to have a low SLDTR due to temporary circumstances (such as departure of a transplant surgeon).

In order to maintain consistency in the direction of the odds ratios between our first and second analyses, the outcome for the second logistic regression model was being a center in the upper three quartiles of SLDTR for at least four years. For example, if a center’s use of unrelated donors increased individual access to LDKTx and raised a center’s SLDTR ranking, this practice would be associated with an odds ratio >1 in both analyses.

Missing data

A minority of patients had missing data on education and income. Additionally, recipients of live donor transplants who were not wait-listed lacked data on peak PRA (n=8,087, or 11.6% of the cohort). For our multivariable analyses, we performed multiple imputation to account for missing data.

Secondary analyses

We fit a multivariable linear regression model for the outcome of the center-specific proportion of live donor kidney transplants (live donor transplants/all transplants). We evaluated the same independent variables used in the primary analysis as well as median waiting time in the center’s donor service area.

We also calculated an SLDTR using a “measurement window” of 2.5 years within which LDKTx took place and repeated multivariable regression analyses.

Additionally, we performed two sensitivity analyses in which the imputed days between transplant readiness and transplant was 84 days (the 25th percentile for number of days between wait-listing and LDKTx for recipients who were wait-listed) and 274 days (the 75th percentile).

Statistical analyses

Analyses were performed using SAS (Version 8, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, N.C., U.S.A.) and Stata (Version 10.0, Stata Corporation, College Station, T.X., U.S.A.). For unadjusted comparisons of continuous variables, the t-test or the rank-sum test were used, as appropriate. The chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables. The primary multivariable analyses were performed using logistic regression; the Hosmer-Lemeshow hypothesis of good fit was not rejected (p>0.05).

Abbreviations

- HHI

Herfindahl-Hirschman Index

- LDKTx

Live donor kidney transplantation

- PRA

Panel reactive antibody

- SLDTR

Standardized live donor transplant ratio

- UNOS

United Network for Organ Sharing

- US

United States

Footnotes

Dr. Reese is supported by NIH Career Development Award, K23 - DK078688-01. He participated in research design, data analysis and writing of the paper

Dr. Feldman is supported by NIH grant K24 - DK002651. He participated in research design and writing of the paper

Dr. Bloom participated in research design and writing of the paper

Dr. Abt participated in research design and writing of the paper

Ms. Thomasson participated in data analysis and writing of the paper

Dr. Shults participated in research design, data analysis and writing of the paper

Dr. Grossman participated in research design and writing of the paper

Dr. Asch participated in research design and writing of the paper.

UNOS Disclaimer: “This work was supported in part by Health Resources and Services Administration contract 234-2005-370011C. The content is the responsibility of the authors alone and does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.”

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

Addresses:

* Drs. Reese, Feldman and Shults and Ms. Thomasson: Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Blockley Hall, 423 Guardian Drive, Philadelphia, PA 19104

* Dr. Bloom: Renal Division, HUP, the Renal Division, 1 Founders Pavilion, 3400 Spruce Street, Philadelphia, PA, 19104

* Dr. Abt: Transplant Surgery, HUP, 1 Founders Pavilion, 3400 Spruce Street, Philadelphia, PA, 19104

* Dr. Asch: Leonard Davis Institute, 3461 Locust Walk, Philadelphia, PA, 19104

* Dr. Blumberg: Infectious Diseases Division, HUP, 3400 Spruce Street, Philadelphia, PA, 19104

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Davis CL, Delmonico FL. Living-donor kidney transplantation: a review of the current practices for the live donor. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(7):2098. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004100824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kasiske BL, Snyder JJ, Matas AJ, Ellison MD, Gill JS, Kausz AT. Preemptive kidney transplantation: the advantage and the advantaged. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13(5):1358. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000013295.11876.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rector TS, Wickstrom SL, Shah M, et al. Specificity and sensitivity of claims-based algorithms for identifying members of Medicare+Choice health plans that have chronic medical conditions. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(6 Pt 1):1839. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00321.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lawthers AG, McCarthy EP, Davis RB, Peterson LE, Palmer RH, Iezzoni LI. Identification of in-hospital complications from claims data. Is it valid? Med Care. 2000;38(8):785. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200008000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Segev DL, Gentry SE, Warren DS, Reeb B, Montgomery RA. Kidney paired donation and optimizing the use of live donor organs. JAMA. 2005;293(15):1883. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.15.1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takahashi K, Saito K, Takahara S, et al. Excellent long-term outcome of ABO-incompatible living donor kidney transplantation in Japan. Am J Transplant. 2004;4(7):1089. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00464.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.USRDS . Annual Report, Figure 7.2, Volume 2: Counts of transplants from living donors, by donor relation. National Institutes of Health, National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; Bethesda, MD: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ratner LE, Ciseck LJ, Moore RG, Cigarroa FG, Kaufman HS, Kavoussi LR. Laparoscopic live donor nephrectomy. Transplantation. 1995;60(9):1047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Montgomery RA, Zachary AA, Racusen LC, et al. Plasmapheresis and intravenous immune globulin provides effective rescue therapy for refractory humoral rejection and allows kidneys to be successfully transplanted into cross-match-positive recipients. Transplantation. 2000;70(6):887. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200009270-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanabe K, Takahashi K, Sonda K, et al. Long-term results of ABO-incompatible living kidney transplantation: a single-center experience. Transplantation. 1998;65(2):224. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199801270-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Axelrod DA, McCullough KP, Brewer ED, Becker BN, Segev DL, Rao PS. Kidney and pancreas transplantation in the United States, 1999-2008: the changing face of living donation. Am J Transplant. 10(4 Pt 2):987. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Segev DL, Kucirka LM, Oberai PC, et al. Age and Comorbidities Are Effect Modifiers of Gender Disparities in Renal Transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009 doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008060591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Epstein AM, Ayanian JZ, Keogh JH, et al. Racial disparities in access to renal transplantation--clinically appropriate or due to underuse or overuse? N Engl J Med. 2000;343(21):1537. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011233432106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lunsford SL, Simpson KS, Chavin KD, et al. Racial disparities in living kidney donation: is there a lack of willing donors or an excess of medically unsuitable candidates? Transplantation. 2006;82(7):876. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000232693.69773.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jindal RM, Ryan JJ, Sajjad I, Murthy MH, Baines LS. Kidney transplantation and gender disparity. Am J Nephrol. 2005;25(5):474. doi: 10.1159/000087920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Young CJ, Gaston RS. Renal transplantation in black Americans. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(21):1545. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011233432107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boulware LE, Ratner LE, Sosa JA, et al. The general public’s concerns about clinical risk in live kidney donation. Am J Transplant. 2002;2(2):186. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2002.020211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gore JL, Danovitch GM, Litwin MS, Pham PT, Singer JS. Disparities in the utilization of live donor renal transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(5):1124. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weng FL, Reese PP, Mulgaonkar S, Patel AM. Barriers to Living Donor Kidney Transplantation among Black or Older Transplant Candidates. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010 doi: 10.2215/CJN.03040410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ross LF, Rubin DT, Siegler M, Josephson MA, Thistlethwaite JR, Jr., Woodle ES. Ethics of a paired-kidney-exchange program. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(24):1752. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199706123362412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bloembergen WE, Port FK, Mauger EA, Briggs JP, Leichtman AB. Gender discrepancies in living related renal transplant donors and recipients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1996;7(8):1139. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V781139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reese P, Oyedeji A, Grossman R. Race and living kidney donors. Transplantation. 2007;83(8):1139. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000259750.90770.69. author reply 1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lentine KL, Schnitzler MA, Xiao H, et al. Racial Variation in Medical Outcomes among Living Kidney Donors. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363:724. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gordon EJ, Wolf MS. Health literacy skills of kidney transplant recipients. Prog Transplant. 2009;19(1):25. doi: 10.1177/152692480901900104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gordon EJ, Caicedo JC, Ladner DP, Reddy E, Abecassis MM. Transplant center provision of education and culturally and linguistically competent care: a national study. Am J Transplant. 2010;10(12):2701. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vo AA, Lukovsky M, Toyoda M, et al. Rituximab and intravenous immune globulin for desensitization during renal transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(3):242. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reese PP, Caplan AL, Kesselheim AS, Bloom RD. Creating a medical, ethical, and legal framework for complex living kidney donors. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1(6):1148. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02180606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reese PP, Feldman HI, McBride MA, Anderson K, Asch DA, Bloom RD. Substantial variation in the acceptance of medically complex live kidney donors across US renal transplant centers. Am J Transplant. 2008;8(10):2062. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02361.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Young A, Storsley L, Garg AX, et al. Health Outcomes for Living Kidney Donors with Isolated Medical Abnormalities: A Systematic Review. Am J Transplant. 2008 doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steiner RW. Risk appreciation for living kidney donors: another new subspecialty? Am J Transplant. 2004;4(5):694. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Segev DL, Gentry SE, Montgomery RA. Association between waiting times for kidney transplantation and rates of live donation. Am J Transplant. 2007;7(10):2406. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scanlon DP, Hollenbeak CS, Lee W, Loh E, Ubel PA. Does competition for transplantable hearts encourage ‘gaming’ of the waiting list? Health Aff (Millwood) 2004;23(2):191. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hirschman A. The paternity of an index. American Economics Review. 1964;54:761. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reese PP, Yeh H, Thomasson AM, Shults J, Markmann JF. Transplant center volume and outcomes after liver retransplantation. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(2):309. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02488.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herfindahl O. Economics, vol PhD. New York: Columbia: 1950. Concentration in the US Steel Industry. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rothman KJ, Greenland S. Modern Epidemiology. 2nd ed Lippincott-Raven; Philadelphia: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wolfe RA. The standardized mortality ratio revisited: improvements, innovations, and limitations. Am J Kidney Dis. 1994;24(2):290. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)80194-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wright J, Dugdale B, Hammond I, et al. Learning from death: a hospital mortality reduction programme. J R Soc Med. 2006;99(6):303. doi: 10.1258/jrsm.99.6.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]