Abstract

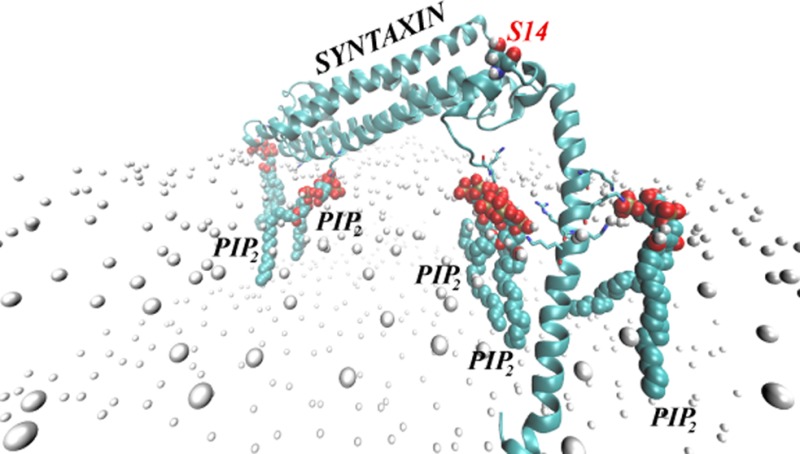

Syntaxin (STX) is a N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor (SNARE) protein that binds to the plasma membrane and regulates ion channels and neurotransmitter transporters. Experiments have established the involvement of the N-terminal segment of STX in direct protein–protein interactions and have suggested a critical role for the phosphorylation of serine 14 (S14) by casein kinase-2 (CK2). Because the organization of STX in the plasma membrane was shown to be regulated by phosphatidylinositol 4,5-biphosphate (PIP2) lipids, we investigated the mechanistic involvement of PIP2 lipids in modulating both the membrane interaction and the phosphorylation of STX, using a computational strategy that integrates mesoscale continuum modeling of protein–membrane interactions, with all-atom molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. Iterative applications of this protocol produced quantitative evaluations of lipid-type demixing due to the protein and identified conformational differences between STX immersed in PIP2-containing and PIP2-depleted membranes. Specific sites in STX were identified to be important for the electrostatic interactions with the PIP2 lipids attracted to the protein, and the segregation of PIP2 lipids near the protein is shown to have a dramatic effect on the positioning of the STX N-terminal segment with respect to the membrane/water interface. This PIP2-dependent repositioning is shown to modulate the extent of exposure of S14 to large reagents representing the CK2 enzyme and hence the propensity for phosphorylation. The prediction of STX sites involved in such PIP2-dependent regulation of STX phosphorylation at S14 offers experimentally testable probes of the mechanisms and models presented in this study, through structural modifications that can modulate the effects.

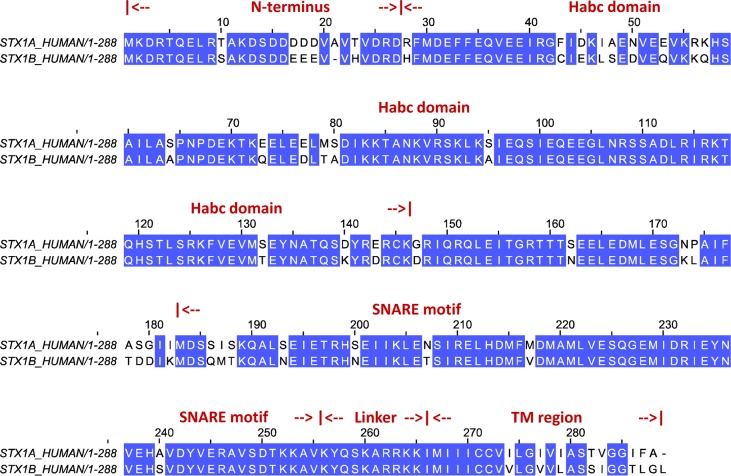

As a component of the soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor (SNARE) complex, syntaxin (STX) participates in the regulation of neurotransmitter release into the synaptic cleft by participating in the process of synaptic vesicle fusion with the membrane of the nerve cell.1 The sequence alignment for the 1A and 1B isoforms of STX (Figure 1) identifies the known functional segments of this plasma membrane-associated multidomain protein: the N-terminus stretch, the triply helical (Habc) regulatory domain, a SNARE motif, and a membrane-anchoring C-terminal transmembrane (TM) segment which is connected to the SNARE fragment through a linker region.2

Figure 1.

Sequence alignment of two human syntaxin 1 isoforms: Syntaxin 1A (top row) and Syntaxin 1B (bottom row). Sequence identity of these two isoforms is 83%. For completeness, the alignment also shows the location of different domains of syntaxin.

Two structurally distinct conformations of STX are known (see refs (3 and 4) and references therein). During vesicular fusion, STX is considered to be in the “open” conformation in which its SNARE motif forms an extended and intertwined four α-helix bundle structure with other members of the SNARE complex (SNAP-25 and synaptobrevin 2).1,2,4 Recent X-ray structural analysis and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of such a neuronal SNARE core revealed that the helical region on STX continuously extends from the SNARE motif toward the C-terminus and includes both the linker and the TM segments.5

In the structurally “closed” state, STX can bind the cytosolic protein Munc18a, one of the proteins known to regulate the vesicular fusion process (for reviews see refs (3 and 4)). The refined X-ray structure of a Munc18a-STX complex6 showed that in the “closed” state, the SNARE motif of STX is folded onto the Habc domain and is involved in interaction with Munc18a. In addition, the stretch of the N-terminus segment (residues 2–9) of STX was found in the crystallographic structure to be partially helical and in contact with Munc18a.

The transitions of STX between these structurally different open and closed states3,6 are not well characterized, yet it is clear that in the open conformation, STX can be anchored to the plasma membrane only through the TM domain, whereas the rest of the protein is expected to extend away from the lipid bilayer. In the closed state, however, the Habc domain, the SNARE motif, and even the N-terminus stretch could all interact with the plasma membrane. The consequences of such juxtamembrane positioning are likely to be very important functionally because STX has been implicated in the regulation of neurotransmitter transporters (NTs) such as the dopamine transporter (DAT),7−9 as well as of NET and SERT, the norepinephrine and serotonin transporters in the same family.10,11 Furthermore, phosphorylation of STX at S14 in the N-terminus segment, by casein kinase-2 (CK2),12−15 has been suggested to have dramatic effects on DAT/STX localization and subsequently on DAT synaptic transmission,16−18 all of which indicates that during cell signaling STX is engaged in regulated, functionally relevant interactions with DAT through its own N-terminus. Steric considerations indicate that for such interaction to take place, STX must adopt conformations that are similar to the closed state, so as to allow the N-terminal region to achieve a juxtamembrane position in which it can interact with the N-terminus of DAT.

The proximity of the STX cytosolic domain to the membrane may also impact the organization and function of STX through interactions with membrane components. Thus, several studies have identified a regulatory role for highly charged phosphatidylinositol 4,5-biphosphate (PIP2) lipids in the clustering of STX in lipid domains.19−21 Specifically, when STX construct including residues 183–288 (STX183–288) was reconstituted into model lipid membranes and investigated with fluorescence quenching or FRET experiments, the cluster formation by this construct was shown to be dependent on PIP2 and cholesterol content; addition of as little as 1–5% PIP2 lipid reversed cholesterol-driven STX clustering.19 Interestingly, a follow-up study by the same authors20 showed that PIP2 lipids are capable of disrupting STX183–288 clustering even in the presence of physiological concentrations of weakly charged (−1 charge) phosphatidylserine (PS) lipid, which was attributed to the strong electrostatic forces between acidic PIP2 lipids and the positively charged stretch K259-A260-R261-R262-K263-K264 (KARRKK) in the STX linker region of the protein.19,20,22,23 But because these studies utilized STX construct lacking both the Habc and the N-terminal region, the authors could not address the consequences of electrostatic interactions between PIP2 lipids and basic residues residing in these domains of STX (Figure 1). This is taken up in a more recent study, in PC12 cells, that confirmed the importance of electrostatic protein–lipid interactions by showing that the electrostatic forces between STX and PIP2 can drive STX sequestration into PIP2-enriched domains.21 Reconstitution of PIP2 lipids and the C-terminal part of STX (residues 257–288, STXTM) into giant unilamellar vesicles resulted in segregation of STXTM and PIP2 into microdomains, and coarse-grained MD simulations showed spontaneous PIP2 lipid-driven STXTM sequestration.21 Still, details about STX-PIP2 lipid interactions in a structural context of the full-length protein are missing despite the detailed experimental19−23 and computational21,24 explorations.

To gain such insights, assess the mechanistic involvement of PIP2 lipids in functionally important STX phosphorylation, and develop experimentally testable hypotheses, we considered (i) the specific mechanistic phenotypes, and (ii) the functionally relevant structural elements in STX, that can be modulated by phosphorylation or PIP2 depletion. To this end we carried out a quantitative evaluation of the role of interactions between STX and PIP2 lipids in determining both the conformational preferences of STX as a whole, and the disposition of its N-terminal domain in particular (since this region contains the S14 residue targeted by the CK2 kinase). We applied a multiscale computational protocol, which combines iteratively the recently developed mean-field mesoscale approach to model protein–lipid interactions25−27 with atomistic MD simulations, to study the dynamics of a full length STX protein model in its “closed” conformation, embedded in PIP2-rich, or PIP2-depleted, lipid membranes. This approach allowed us to sample efficiently both long-time lipid kinetics and STX conformational dynamics.

We observed demixing of PIP2 lipids in the membrane bilayer containing 5% PIP2, and a segregation of PIP2 lipids around STX that was driven by their strong electrostatic interactions with STX at specific sites (our simulations established that as many as five PIP2 lipid molecules can simultaneously bind STX). The location of the critical interaction sites was not confined to the juxtamembrane region of STX (TM segment/linker), but also included the N-terminus stretch and the Habc domain. By comparing STX conformational dynamics in PIP2-rich and PIP2-depleted bilayers we established that the segregation of PIP2 lipids has a profound effect on the positioning of the STX N-terminal segment with respect to the membrane/water interface, stabilizing it in a conformation where the Serine14 targeted by the CK2 kinase is highly accessible. In contrast, we show here that if the electrostatic interactions are diminished or eliminated, e.g., for a Lys2Ala (K2A) STX mutant designed to test the findings, or in simulations of STX in pure POPC membranes in the absence of PIP2, then the STX N-terminus adopts structural conformations in which S14 is occluded and less accessible to the kinase. These predictions from the computational study suggest that the ability of CK2 to phosphorylate STX at S14 is dependent on the interaction with PIP2-rich domains of the cell membrane and would be diminished upon decreasing cellular levels of PIP2.

Methods and Procedures

Atomistic Model of Full-Length STX

The complete structure of full-length STX has not been determined, but much structural information for different regions of STX is available from a number of X-ray crystallography and NMR studies.5,28−38 Our atomistic model of the full-length Syntaxin 1B in a “closed” state was constructed with the use of data from several high-resolution X-ray structures of STX complexes, complemented with results from structure-prediction methods (see below). The sequence of syntaxin 1B is highly conserved among species (i.e., human, mouse, and rat), and the 1A and 1B isoforms of human syntaxin share ∼83% sequence conservation (Figure 1). For these reasons, we simplify notations by using the STX abbreviation throughout the text to refer to both 1A and 1B isoforms of syntaxin.

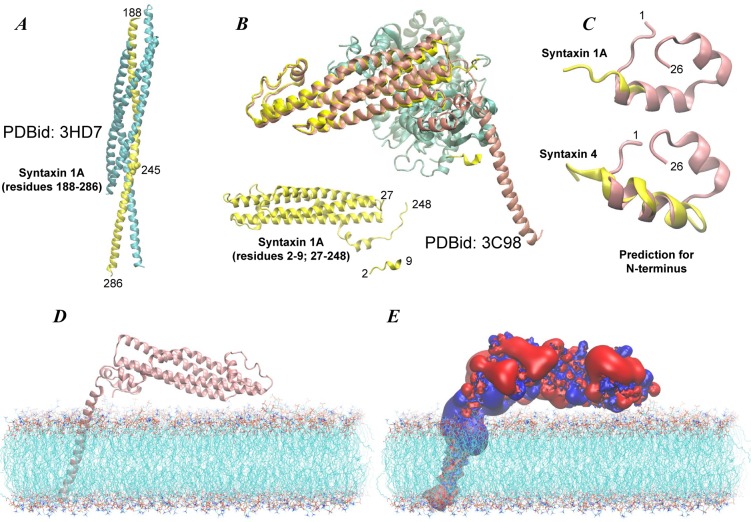

The template for the full-length STX in a closed state consisted of two specific X-ray structures of STX (Figure 2A,B): One from its complex with the neuronal SNARE proteins5 (PDBid: 3HD7) and another from its complex with the Munc18a protein6 (PDBid: 3C98). In the 3HD7 structure (see Figure 2A), the STX C-terminus region (from residue 188 to 286 including the SNARE motif, linker region, and the TM segment) is in an “open” extended helical conformation and in complex with other SNARE proteins. In the 3C98 structure, the 27–248 residue stretch of STX, which includes the Habc domain and part of the SNARE motif (see Figure 2B and the alignment in Figure 1), is in a “closed” state and in contact with the Munc18a protein. In addition, this structure also includes a resolved piece of the STX N-terminal region (residues 2–9) found to be near helical and interacting with Munc18a.

Figure 2.

The “closed” state model of syntaxin was built by combining two high resolution X-ray structures (3HD7 and 3C98) with the model of the N-terminus predicted with Rosetta. (A) In 3HD7, the stretch of residues 188–286 of syntaxin 1A (yellow) forms an extended intertwined helical bundle with other SNARE proteins, Snap-25 and synaptobrevin-2 (cyan). The structural information from 3HD7 was used to model residues 188–245 (shown in space fill rendering in yellow in panel A). (B) In 3C98, syntaxin 1A is in the “closed” state (yellow) and in complex with Munc18a protein (cyan). Residue segments 2–9 and 27–248 have been resolved in this structure and are shown without Munc18a. Panel B also illustrates how the “closed” state model of STX (pink) superimposes on the structural model in 3C98. (C) Fold prediction from Rosetta for the N-terminus region of STX. Upper and lower panels show alignments of the predicted structure for the N-terminal 1–26 residue stretch (pink) with X-ray structures of syntaxin 1 and syntaxin 4 N-peptides (yellow), respectively. Crystallographic models for syntaxin 1 (residues 2–9) and syntaxin 4 (residues 1–19) N-peptides were taken from PDBid 3C98 and 2PJX, respectively. The root-mean-square deviation (rmsd) for the aligned helical regions was 1 Å for syntaxin 1 and 2.3 Å for syntaxin 4. (D) Orientation of the “closed” state STX (cartoon) with respect to the lipid membrane (lines). Intracellular and extracellular leaflets are top and bottom leaflets respectively. The membranes consisted of either mixture of neuronal lipids (5:45:50 PIP2/POPE/POPC on the intracellular leaflet and 30:70 sphingomyelin/POPC on the extracellular leaflet, referred to as the PM membrane in the text) or contained only POPC lipid, ∼800 lipids in total. (E) Electrostatic potential isosurfaces for STX at +25 eV (positive, blue) and −25 eV (negative, red) levels in the same orientation as in panel D. The electrostatic calculation was performed using APBS software version 4.0.

The Modeller suite of programs39 was used to combine the two structure components of STX, 3C98 (residues 27–248) and 3HD7 (residues 245–286) into a “closed state”-like fold of the full-length protein. (We note that combining these crystallographic models using different criteria, e.g., residues 27–190 from 3C98 and residues 188–286 from 3HD7, produces an extended conformation of the protein, consistent with the “open” state). To complete the “closed STX model”, we built the crystallographically disordered portion of the STX N-terminus region (residues 1–26) using the knowledge-based structure prediction tool Rosetta.40 Structure predictions from Rosetta were filtered through clustering, and 1000 different structures were obtained and clustered according to a criterion of maximization of common structure conservation (calculated with the in-house algorithm RMSDTT41 now implemented in VMD42). Clusters including the largest numbers of conformations (usually 2–3 top clusters for each construct) were thus identified and further refined to find the most conserved motifs within each cluster.

Figure 2C shows the predicted fold of the STX N-terminus, and Figure 2B shows the alignment of the modeled full-length STX with the STX in the 3C98 structure, illustrating not only the very similar fold of the Habc and SNARE domains, but also the structural correspondence between the N-terminal residues 2–9 in our predicted model and in the 3C98 structure (Figure 2C, upper panel). Furthermore, we find that the computationally derived model for the N-terminus is similar to the structure (PDBid: 2PJX) of the N-peptide from syntaxin 4 (STX4) protein, which has high sequence similarity (∼70%) to the N-terminal stretch of STX that was crystallized in the complex with Munc18c.38 As shown in Figure 2C (lower panel), the 1–19 stretch of the STX4 N-peptide from 2PJX aligns well with the predicted structure (with a root-mean square deviation (rmsd) of ∼2.3 Å for backbone atoms of residues 4–16). Importantly, we note that the predicted fold of the full-length STX brings the N-terminus to a juxtamembrane position near the TM segment/linker region (Figure 2D). As shown in Figure 2E and discussed below, the proximity of the N-terminus and TM stretch to the membrane, generates a large positive electrostatic potential near the bilayer surface, which is thus expected to have a strong effect on PIP2 lipid sequestration.

An Iterative Approach Using Coarse-Grained and Atomistic Descriptions to Quantify Interactions between STX and PIP2 Lipids

The process of PIP2 lipid segregation near STX was modeled with an iterative approach combining all-atom MD simulations with mesoscale simulations using the self-consistent mean-field model, CGM, that we have formulated and implemented as described previously.25−27 In our combined iterative approach, CGM is used first to calculate the steady state lipid distributions around the protein, and the corresponding free energies, and the resulting equilibrium lipid distributions constitute the starting configuration of the STX/membrane complex in the subsequent all-atom MD simulations (see below).

In the CMG approach a coarse-grained representation of proteins and membranes is obtained by using information about the material properties of proteins, membranes, and their lipid components, as well as their interactions. The resulting coarse-grained model treats the membrane as a two-dimensional, tensionless, incompressible, low-dielectric medium, whereas the protein is treated in 3D full atomistic detail, and the entire protein/membrane complex is immersed in high-dielectric solution media.25−27

The first step in the mesoscale simulation is the definition of the steady state of membrane-associated proteins with the degrees of freedom (i.e., electrostatics, lipid mixing) determined self-consistently from the minimization of the governing mean-field based free energy functional F.25−27 This functional includes contributions from the relevant degrees of freedom and depends on local lipid component densities φ(x,y). The composition field φ(x,y) relates to the surface charge densities σ(x,y) through σ(x,y) = (e/a)φ(x,y)z(x,y), where z(x,y) denotes valency of the lipid at (x,y), a is the area per lipid headgroup, and e represents the elementary charge. As demonstrated earlier,43,44 minimization of F with respect to concentrations of the mobile ions in the solution (which contribute to the electrostatic interactions) leads to a nonlinear Poisson–Boltzmann (NLPB) equation:

| 1 |

The solution of eq 1 yields the reduced electrostatic potential Φ in space (λ being the Debye length of the electrolyte solution). This electrostatic potential is self-consistently dependent on the local lipid concentrations through the entropic penalty due to lipid segregation (demixing)45−47 on the upper and the lower surfaces of the membrane. Within CGM a self-consistent search for the free energy minimum is carried out by linking the electrostatic potential Φ and the spatial charged-lipid compositions φ on each leaflet of the membrane, to the respective electrochemical potentials μ through the Cahn–Hilliard (CH) equation:48

| 2 |

Here Dlip is the lipid diffusion coefficient that should not affect the equilibrium state.

To obtain a quantitative description of STX/PIP2 interactions in different functional states of STX, the CGM approach for the multicomponent membrane is iteratively combined with atomistic MD simulations that start from the lipid compositions in the steady state lipid distributions around STX predicted from the CGM calculations. The MD simulations probe the conformational changes in the protein in response to lipid rearrangements. New lipid distributions that correspond to the conformational changes in STX are then obtained by transforming back the atomistic representations into coarse-grained descriptions for CGM minimization. The iterations between CGM and atomistic MD calculations are done until convergence is achieved.

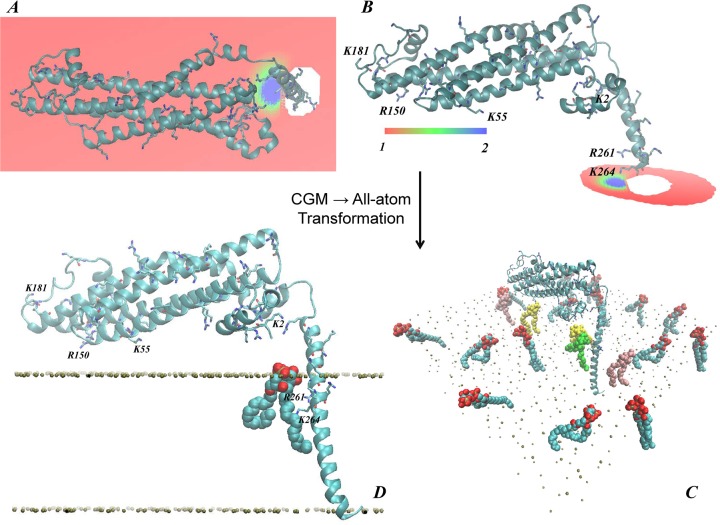

All Atom MD Simulations

The all atom representations of the STX/membrane complex were constructed with the CHARMM-GUI membrane-builder web-tool.49 To mimic a lipid composition in typical plasma membrane,50 we chose a compositionally asymmetric lipid bilayer (referred to throughout as the “PM membrane”), with a composition of 5:45:50 PIP2/POPE(phosphatidylethanolamine)/POPC(phosphatidylcholine) on the intracellular (IC) leaflet, and 30:70 sphingomyelin (SM)/POPC on the extracellular (EC) leaflet. Because PIP2 and SM lipids are not part of the standard CHARMM-GUI lipid library, an atomistic lipid bilayer was assembled first as a homogeneous mixture of 5:45:50 DAPC(diarachidoylphosphatidylcholine)/POPE/POPC lipids on one leaflet, and 30:70 DPPC (dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine)/POPC lipids on the other leaflet. All DAPC and DPPC lipids where then replaced with PIP2 and sphingomyelin (SM) lipids respectively. On the basis of the CGM results from the first iteration (Figure 3A,B), full-length STX was inserted into the PM bilayer such that a single PIP2 lipid ended up positioned near (within 2 Å of) the R261/K264 pair of residues (shown in green in Figure 3C and also highlighted in Figure 3D), and four other PIP2 lipid molecules were positioned at distance 6 Å < d < 10 Å from STX (lipids depicted in yellow and pink in Figure 3C). Overall, the IC leaflet contained 396 lipids, and the EC leaflet consisted of 400 lipids. The STX/PM complex was then solvated and ionized with 0.1 M Na/Cl for electroneutrality, for a final count of 321073 atoms in the system.

Figure 3.

Multiscale modeling of the STX embedded in PM (neuronal plasma membrane model). Panels (A, B) and (C, D) depict coarse-grained and all-atom representations of the system, respectively. In all the panels STX is shown in cartoon with Lys and Arg residues highlighted in licorice. (A) Steady-state distribution of PIP2 lipids (colored shades represent ratios of local φ and average φ0 lipid fraction values) from the CGM minimization procedure. STX1–246 was used for this calculation (see text), and the intracellular (IC) membrane leaflet facing STX started with a uniform composition of φ0PIP2 = 0.05 and φ0POPC+POPE = 0.95. For clarity, only the part of the bilayer leaflet near the protein is shown. (B) Similar to panel (A) but showing the segment of the IC leaflet for which the CGM calculation predicts an excess of PIP2 lipids (φ/φ0 >1) at equilibrium. Several key Lys/Arg residues are highlighted. (C) Initial placement of PIP2 lipids (shown in space-fill) in the all-atom construct of STX in PM. On the basis of the findings from the CGM minimization, one PIP2 (in green) was placed within 2 Å of the R261/K264 residue pair. Two PIP2 lipids (in yellow) were located 6 Å away from the protein, and two other PIP2 lipids (in pink) were positioned 10 Å away from STX. Bilayer leaflets are indicated by the phosphate atoms in their lipid head-groups (shown in gold), and the rest of the system is removed for clarity. (D) Zoom-in on the region where the strongest electrostatic interaction between STX and PIP2 is expected. Color code is the same as in (C).

All MD simulations were performed with the NAnoscale Molecular Dynamics (NAMD) suite51 using constant temperature and pressure conditions with semi-isotropic pressure coupling, and utilizing PME for long-range electrostatics.52 The all-atom CHARMM27 force field with CMAP corrections for proteins,53 and the recently improved CHARMM36 force fields for POPE and POPC lipids54 were used throughout. For SM and PIP2, we used CHARMM36-compatible all-atom force field parameter sets described in refs (55) and (56), respectively. The Nose-Hoover Langevin piston method51,57 was used to control the target pressure with the LangevinPistonPeriod set to 100 fs and LangevinPistonDecay set to 50 fs. All MD simulations were performed with rigidBonds allowing 2 fs time step. The simulated systems were equilibrated for 5 ns following a procedure described recently.58 According to this protocol, the STX backbone was initially fixed and then harmonically constrained, and water was prevented from penetrating the protein TM-lipid interface. Constraints were released gradually in four 300 ps-step MD simulations with decreasing force constants of 1, 0.5, 0.1, and 0.01 kcal/(mol·Å2), respectively. Following this equilibration phase, the STX/PM complex was simulated for 90 ns. In all MD simulations, STX was capped with standard charged N- and C-termini.

Starting with CGM calculations for the STX model and homogeneous lipid distributions of various compositions, the iterative protocol was applied only for the IC leaflet because charged PIP2 lipids (−4 charge at neutral pH59) are not included in the EC leaflet (see above). This was done by creating appropriate average fractions (i.e., φ0PIP2 = 0.05, φ0POPC+POPE = 0.95, corresponding to the average surface charge density of σ0 = −0.0031e). For simplicity, this charged surface was assumed to remain planar in the course of the CGM minimization.

According to the protocol,27 the protein, STX, was considered in full atomistic detail throughout, with partial charge and atomic radii taken from the all-atom CHARMM27 force field with CMAP corrections for proteins53). To solve the NLPB eq 1 we considered only the 1–264 residue stretch of STX (STX1–264) that includes all the basic amino acids but excludes most of the TM segment (Figure 3). This partial structure was used only in the CGM level simulations where the neglected part of the TM domain is not expected to affect electrostatic interactions of STX with PIP2.

MD Simulations of STX in POPC Membranes

STX was also simulated in pure POPC membranes containing 710 lipids (270 052 atoms in total), using NAMD. The simulation protocol used was the same as described above, and the system was simulated for 100 ns after the initial equilibration phase (see above).

Simulations of the STX K2A Mutant in PM

All-atom MD simulations of an STX K2A mutant (STXK2A) in the PM membrane started with the K2A mutation carried out with VMD on the STX structure used in the initial CGM minimization procedure (see above, and also Figures 2 and 3). The starting distribution of lipids around STXK2A was taken from the initial point of the wild type STX all-atom MD simulations in PM mixture (Figure 3). After solvating and ionizing, the STXK2A/PM complex was simulated for 100 ns beyond the initial equilibration phase, under the simulation conditions identical to those described above.

Analysis of Atomistic Trajectories

Stability and convergence of all three atomistic MD simulations (STX wild type in PM and in POPC membranes, and the STX K2A mutant in PM) were monitored by tracking the rmsd profiles for the protein in the respective simulations, which were largely unchanged for the later halves of the trajectories (data not shown).

Calculation of Solvent Accessible Surface Areas (SASA) from All-Atom MD Trajectories

SASAs were calculated with the NACCESS package.60 NACCESS implements the standard solvent accessibility definition introduced by Lee and Richards61 which makes use of rolling a spherical probe of rp radius on the van der Waals surface of the protein. SASA for a particular atom on the protein is then calculated as the area on the surface of a sphere of radius R, on each point of which the center of the probe molecule can be placed in contact with this atom without penetrating any other atoms of the protein. The radius R is defined as a sum of the van der Waals radius of the atom and rp.

Quantification of Helix Distortions in All-Atom MD Trajectories

Structural perturbations related to helix kink or twist in STX TM segment were quantified with the ProKink package62 in the publicly available software Simulaid.63 Geometric definitions and the computational protocol implemented in ProKink are as described previously.62,64

Results

First CGM/MD Round in the Iterative Protocol

CGM 1

The NLPB equation was solved numerically with the APBS multigrid solver on 1 Å-spaced cubic 256 Å3 mesh as described previously,26,27 considering 0.1 M ionic solution of monovalent counterions (corresponding to λ = 9.65 Å Debye length), and using a dielectric constant of 2 for membrane interior and protein, and 80 for the solution. The STX1–264 was positioned initially near the membrane so that the minimum distance between STX1–264 and the lipid surface was 2 Å (Figure 3).

The PIP2 lipid distribution around STX is illustrated in Figure 3 for the equilibrium conditions obtained with the CGM approach; it is inhomogeneous. The obvious segregation of PIP2 is confined to the membrane region near the linker segment of STX (dark shading in Figure 3). Specifically, the strongest effect on PIP2 lipid sequestration seems to come from the electrostatic interactions with residues R261 and K264 that are part of the KARRKK basic stretch on STX. This stretch has been implicated in electrostatic interactions with PIP2 lipids19−23 and has been shown recently through mutation studies to regulate STX clustering.20,21

On the basis of the lateral area of the membrane region where aggregation of PIP2 lipids have been predicted from our CGM minimization (Figure 3B) and assuming a = 65 Å2 for the area per lipid headgroup, we estimated from the distribution pattern in Figure 3B that the number of PIP2 lipids sequestered by STX in the conformation used in these initial CGM calculations is between one and two. Next, we used this information as described in Methods to build the cognate all-atom STX/membrane complex used as the starting point for the subsequent atomistic MD simulations in this first iteration (MD 1).

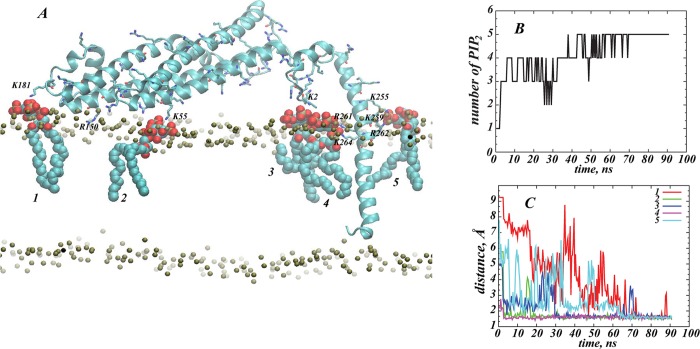

MD 1

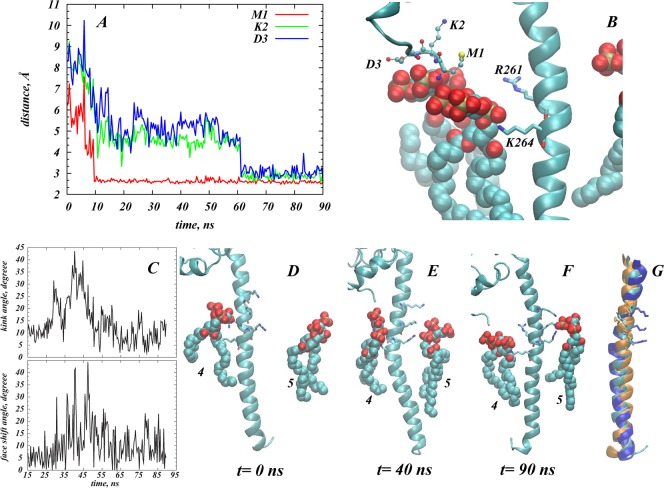

Figure 4A shows a final snapshot of STX in PM after 90 ns of all-atom MD simulations, and Figures 4B–C quantify the dynamics of PIP2 aggregation around STX during the MD trajectory. This atomistic simulation was initiated from the configuration of STX/PM complex from the preceding CMG simulations as described above (see also Figure 3). During the MD simulations, a single STX establishes stable interactions simultaneously with five different PIP2 molecules: in addition to one PIP2 lipid (designated as PIP2 “4” in Figure 4) that was initially placed near the STX linker region, two other PIP2 molecules (“2” and “3” in Figure 4) approached STX within the first few nanoseconds of simulations. One of them (PIP2 “2”) binds to residue K55 in the Habc domain, and the other (PIP2 “3”) to the N-terminal stretch of residues 1–3. Interestingly, PIP2 “3” and PIP2 “4” come together near STX due to electrostatic interactions with residues in both the N-terminus (M1/K2/D3) and the linker region (R261/K264). Two additional PIP2 lipids (“1” and “5” in Figure 4) are sequestered by STX after ∼70 ns. PIP2 “1” establishes interactions with K181 (residue connecting Habc domain to the SNARE motif, see Figure 1), whereas PIP2 “5” is in contact with K255/K259/R262 residue triplet in the linker region.

Figure 4.

STX interacts simultaneously with five PIP2 molecules. (A) Snapshot after 90 ns of atomistic MD simulations of STX/PM complex, showing five different PIP2 lipids (in space fill representation) bound to STX (in cartoon). Key basic residues of STX are highlighted, and PIP2 lipids are numbered for designation purposes. Membrane leaflets are traced by their lipid phosphate atoms (in gold) and for clarity, the rest of the simulated system is removed. (B) Time-evolution of the cumulative number of PIP2 molecules within 3.5 Å of STX, depicted and numbered as in A. (C) Time-evolution of the minimum distances between STX and five PIP2 lipids.

Structural comparison of STX in the initial frame (Figure 3D) and after 90 ns of MD (Figure 4A) shows that concomitant with PIP2 sequestration, substantial changes occur in side-chain orientations of several critical residues. In particular, the side-chains of K181 and K55 reorient during the simulation so that their ε-amino groups face the membrane. The Cα-Cβ-Cγ-Cδ dihedral angle of K55, for example, changed during the initial equilibration phase of the MD simulation (see Methods) from an initial 170° (nearly parallel to the bilayer plane), to 75° (nearly perpendicular), and maintained this membrane-facing conformation for the remainder of the trajectory. Furthermore, dramatic conformational changes are observed in the N-terminus region of STX resulting in movement of M1/K2/D3 residues toward the lipid membrane (see Figure 5A). With this repositioning, the M1/K2/D3 triplet of residues together with the side-chains of R261/K264 from the linker region coordinate the electrostatic interactions with two PIP2 molecules (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Structural elements of STX responsible for PIP2 lipid sequestration. (A, B) Two PIP2 molecules (“3” and “4”, see also Figure 4A) are held near STX by interactions with M1/K2/D3 residues in the N-terminus and R261/K264 in the linker region. (A) Time-evolution of the minimum distance between amino groups of M1 (red), K2 (green), and D3 (blue) and PIP2 molecule “3”. (B) Snapshot after 90 ns of atomistic MD simulations illustrating electrostatic interactions with M1/K2/D3 (drawn in ball and stick) and R261/K264 (licorice). The STX fragment is depicted in cartoon, and PIP2 lipids “3” and “4” are represented in space-fill. (C–G) STX TM/linker helical region undergoes conformational change upon binding of PIP2 lipids. (C) Time-evolution of changes in the 246–288 helix around K264; the kink (upper panel) and face shift (lower panel) angles are calculated with ProKink.62 (D–F) Snapshots of STX TM/linker helix and neighboring PIP2 lipids (“4” and “5” as designated in Figure 4A) taken at trajectory time-points t = 0 ns (D), t = 40 ns (E), and t = 90 ns (F). The helix is shown in cartoon, and K255, K259, and R262 are drawn in licorice. (G) Superposition of conformations of the STX TM/linker helical segment at t = 0 ns (cyan), t = 40 ns (blue), and t = 90 ns (orange) time-points highlighting the face shift in the helix. K255/K259/R262 residues are depicted in licorice.

The Membrane Embedded STX Sequesters Five PIP2 Lipids Simultaneously

Analysis of the MD simulation trajectory reveals a series of structural perturbations and conformational rearrangements that reflect the local interactions of STX with the PIP2 lipids. These dynamic conformational changes include the kinking of the TM segment (residues 265–288), and the twisting (face shift) motion of the TM (Figure 5C–G). All these perturbations observed in the MD trajectory result from the interaction of the polybasic K259-A260-R261-R262-K263-K264 segment with specific PIP2 lipids, and are consistent with experimentally measured synergistic effect that these residues have on PIP2 binding.20 Notably, our results show that in addition to the KARRKK region, other basic residues such as K255 and the K55 and K181 residues in the regulatory Habc domain and the N-terminal segment play important roles in the interactions with PIP2 lipids.

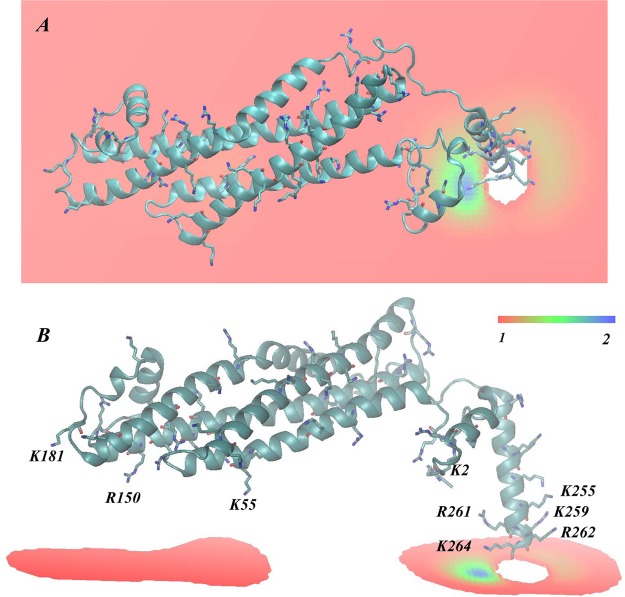

Second CGM Round in the Iterative Protocol

Continuing the iterative protocol, the self-consistent CGM minimization procedure was repeated (CGM 2) using the STX conformation after 90 ns of all-atom MD simulation. As shown in Figure 6, we found that the PIP2 demixing predicted by this round of CGM is different from that obtained with the initial STX model (compare to Figure 5B). Because of the conformational rearrangements described above, STX gained increased ability to sequester multiple PIP2 lipids, as seen in the membrane region facing residues K181/R150/K55. The membrane area exposed to the face of the linker helix containing K255/K259/R262 also exhibits somewhat stronger PIP2 demixing (light brown shades in Figure 6) compared to the CGM predictions from CGM 1 that started with the initial STX model. The estimate for PIP2 lipid sequestration from this round is 4–5 lipids (with two positioned near the K181/R150/K55 cluster of residues) and between two and three PIP2 molecules near the linker region; this CGM result is in excellent agreement with the predictions from the preceding all-atom simulations. Such consistency between the coarse-grained and all-atom representations demonstrates the appropriateness and complementarity of the two approaches for quantification of PIP2 lipid sequestration around STX.

Figure 6.

Results from iteration 2 between CGM minimization and MD equilibration: The steady-state distribution of PIP2 lipids around STX obtained from the CGM minimization scheme using the STX conformation after 90 ns of all-atom MD simulations (shown in Figure 4A). Calculated as in Figure 3, but with an initially uniform composition of the membrane characterized by φ0PIP2 = 0.05 and φ0POPC+POPE = 0.95. (A) Only part of the membrane leaflet near the protein is shown and the CGM solution (color shades) represents ratios of local φ and average φ0 lipid fraction values. (B) Similar to panel A, but showing only regions on the membrane leaflet with excess PIP2 lipids (φ/φ0 > 1).

Control Simulations Substantiate the Role of PIP2 Lipid Sequestration by STX

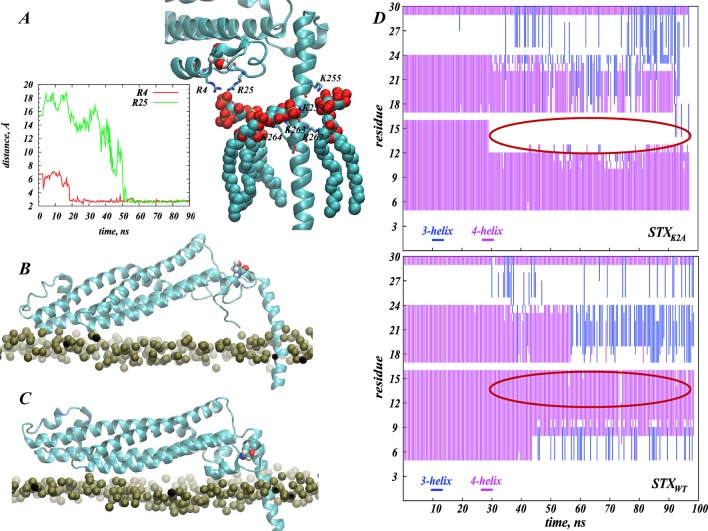

Control simulations included one system in which the STX is immersed in a PIP2-free membrane model (i.e., POPC), and another in which a lysine-to-alanine mutant at position 2, STXK2A, is immersed in the PIP2-containing PM membranes. The K2A mutation was designed in light of the strong tendency of the N-terminus region to interact with sequestered PIP2 lipids, as observed in the MD simulations of STX in PM membranes.

Comparing the STXK2A and STXWT MD simulations, we found a similar extent of PIP2 segregation around STXK2A and STXWT (data not shown). But analysis of the conformational changes in STX N-terminus and its interactions with PIP2 shows that PIP2 lipids sequestered near the protein N-terminus region are stabilized by a different set of interactions in the two simulations. Thus, for the STXK2A system we identified R4 and R25 in the N-terminus as residues responsible for interactions with PIP2 lipids (see Figure 7A), in contrast to the results from the STXWT simulations where the M1/K2/D3 triplet of residues was found to interact with PIP2 lipids. Moreover, in the STXK2A simulations the basic residues in the linker region are seen to coordinate interactions with PIP2 lipids somewhat differently than in the STXWT system. Specifically, as illustrated in Figure 7A, in STXK2A, the K259/K263/K264 group of residues interacts with PIP2 lipids that have been sequestered from the N-terminus-facing side of the linker region, and K255/R262 bind to a single PIP2 lipid that approached the opposite face of the STX juxtamembrane helix. In STXWT, PIP2 lipids aggregated in similar positions were stabilized by R261/K264 and K255/K259/R262 residues, respectively (see Figures 4 and 5).

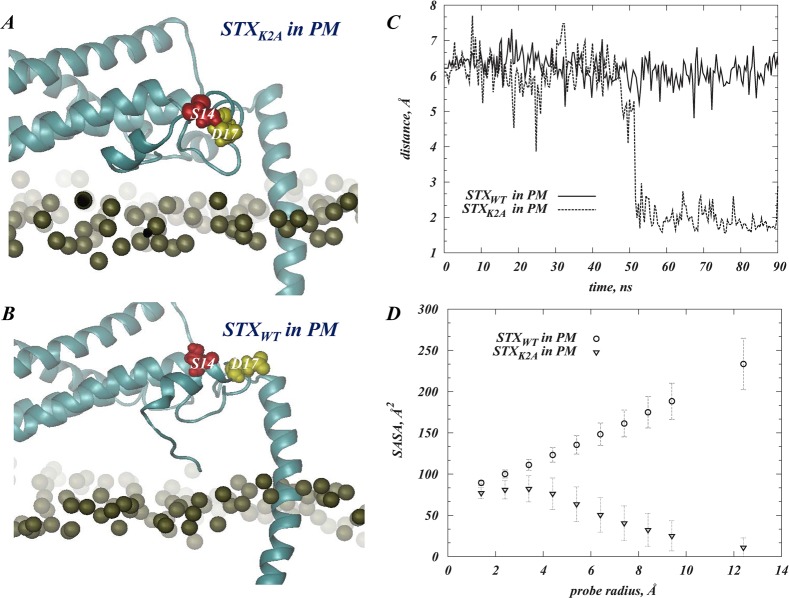

Figure 7.

Different interactions of the N-terminus fragment in wild type (STXWT) and K2A mutant (STXK2A) STX with PIP2 lipids result in distinct conformational changes. (A) Snapshot after 90 ns of MD trajectory of STXK2A (cartoon) highlighting interactions between sequestered PIP2 lipids and residues in the N-terminal and linker regions. Key positions (R4, R25, K255, K259, R262, K263, K264) are shown in licorice. PIP2 molecules and the S14 residue in the STXK2A N-terminus are shown in space-fill. The panel inset describes the evolution in time of minimum distances between PIP2 and residues R4 and R25. (B, C) Differential positioning of S14 (space-fill) in STXWT (in B) and STXK2A (in C). The snapshots were taken after 90 ns of MD simulations in the PM bilayer. The proteins are drawn in cartoon, and the lipid membrane is represented by the location of the lipid headgroup phosphate atoms (gold). (D) Evolution of the secondary structure of N-terminus region (residues 1–30) in STXWT (lower panel) and STXK2A (upper panel) during the simulations. Colors indicate the type of secondary structure: blue for 3-helix, and purple for 4-helix. Changes in colors over trajectory time indicate that the corresponding residue is in one or the other secondary structure at a particular time-point; the red ovals highlight the region near S14 residue, which is seen to assume different secondary structure in the wild type and the mutant STX. The secondary structure assessment was carried out with the Simulaid software.63

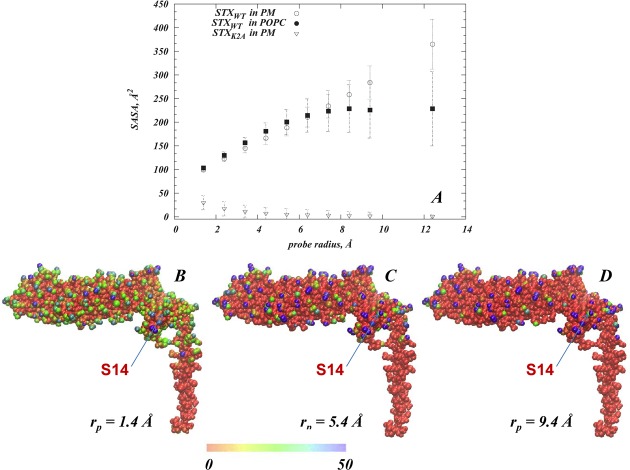

Comparison with the Control Simulations Reveals the Role of STX/PIP2 Interactions in Regulating Access to the Phosphorylation Site S14

Because our goal was to test the hypothesis that the presence of PIP2 lipids in the membrane affects the ability of STX to become phosphorylated by CK2 enzyme at the S14 position, we sought to establish the link between the conformational changes due to the observed STX/PIP2 interactions and the accessibility of that site. To this end, we calculated solvent accessible surface areas (SASAs) with probes of different radii65 in the MD trajectories of all the simulations: STX in PM, STX in POPC membranes, and the lysine to alanine mutant, STXK2A, in PM (see Methods).

By varying the radii rp of the probes used in the SASA calculations we obtain detailed information about the accessibility of the phosphorylation site to reagents of different sizes and bulk. Consequently, Figure 8A compares the SASA calculated for S14 (SASAS14) in the various MD trajectories using probes of different radii, rp. The profile for the wild type STX (STXWT) in PM shows an increase in SASAS14 with increasing rp, which indicates that for STXWT in PM S14 is accessible to a large reagent such as the phosphorylating enzyme. Results in Figure 8B–D further illustrate that S14 in “STXWT in PM” is one of a few residues only for which the SASA value increases for larger probe radii (darker shades in Figure 8B–D), while the majority of positions on STXWT show a decrease in SASA (red shades in Figure 8B–D) upon increasing rp.

Figure 8.

(A) Solvent exposure of the S14 residue in the N-terminus of STX. The profile of the solvent accessible surface area (SASA) of S14 (calculated as described in Methods) is shown as a function of the probe radius, rp, in three MD trajectories: Wild type STX (STXWT) in PM (open circles), STXWT in POPC (filled squares), and K2A STX mutant (STXK2A) in PM (open triangles). The error bars indicate the standard deviations. (B–D) Atomic detail SASA maps for STXWT simulated in PM and measured with different probe radii: rp = 1.4 Å (in B), rp = 5.4 Å (C), and rp = 9.4 Å (D). STXWT in these representative snapshots is shown in space-fill, and each atom of the protein is colored according to its SASA value (see color code). The location of S14 is highlighted in each panel.

In contrast, the accessibility profile for the mutant STXK2A in PM shows that SASAS14 for rp = 1.4 Å is substantially lower than for STXWT in PM, and the larger probe radii produced further decreases in the SASAS14 value suggesting that in the STXK2A construct the S14 site is largely inaccessible to a relevant reagent. The results of the simulations show that these differences in S14 accessibility patterns are brought about by the structural responses of the two STX constructs to the modes of PIP2 sequestration. Thus, the N-terminus region containing the S14 residue in the two constructs is stabilized in structurally different conformation and assumes distinct juxtamembrane position due to the difference in the perturbations produced by PIP2 sequestration (cf. Figure 7B,C). In STXWT, the N-terminal helical stretch (residues 6–16) is positioned farther from the PM membrane surface compared to its location in STXK2A. Furthermore, as illustrated in Figure 7D, residues 12–15 that were in a 4-helix arrangement in STXWT, become unwound in STXK2A (compare secondary structures in the regions highlighted by ovals in the two panels of Figure 7D); this has key mechanistic implications for the accessibility of S14 as discussed below.

Central to our hypothesis regarding the involvement of PIP2 interactions in the phosphorylation of S14, we find that the hydroxyl moiety (OH) of S14 remains solvent accessible in the STXWT simulations, whereas in STXK2A, the OH group becomes occluded due to partial unwinding of the N-terminal helix (Figure 7D). Remarkably, the hydroxyl group on S14 in STXK2A establishes strong interactions with D17 (see Figure 9A–C) as a result of the local change in the secondary structure of the N-terminus, and due to this interaction the D17 side chain is largely occluded in the STXK2A mutant (Figure 9D) whereas in STXWT D17 is highly exposed. This difference is likely to be of critical functional importance because in syntaxin 1B, D17 is part of the highly acidic motif DDEEE (or DDDDD in syntaxin 1A) (see Figure 1); this motif is known to be a specific site-recognition consensus sequence for the CK2 phosphorylating enzyme.66 In fact, recent studies have shown that D17A or D17K mutations on STX disrupted the ability of CK2 to phosphorylate STX.12 The molecular level differences in the N-terminus of the STXWT and STXK2A constructs uncovered in our analysis, which stem from different PIP2 segregation patterns, are thus seen to lead to the differential accessibility of the critical elements for STX phosphorylation (Figures 8A and 9D).

Figure 9.

Residues S14 and D17 exhibit different interaction pattern in STXWT and STXK2A. (A, B) Views of the N-terminus region of STXK2A (in A) and STXWT (in B) interacting with the PM membrane. S14 and D17 are shown in red and yellow space-fill representations, respectively. (C) Minimum distance between S14 and D17 residues as a function of time in simulations of STXWT (solid) and STXK2A (dashed). (D) SASA calculated for D17 residue with probes of different radii, in STXWT (circles) and STXK2A (triangles) simulations.

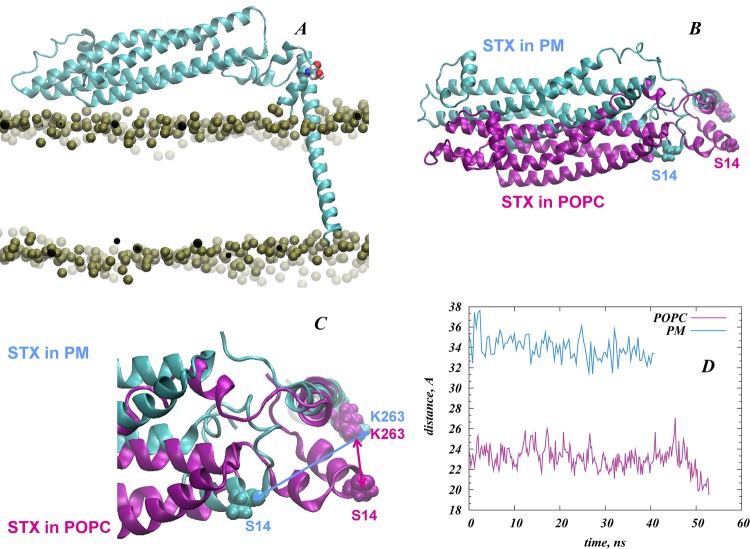

Interestingly, in the computational control experiments in which disruption of the electrostatic interactions between STX and the lipid membrane was achieved by depleting the bilayer of PIP2 (i.e., in simulations of STXWT in POPC membranes), we found diminished S14 exposure when measured with probes of large radii (representing accessibility by a kinase – see Methods). The decrease compared to accessibility measured in PIP2-enriched membranes is evident in Figure 8A from plots corresponding to simulations of STXWT in POPC and PM membranes. To establish the structural mechanisms responsible for this difference, we compared the dynamics of STXWT N-terminus, and of S14 residue in particular, in POPC and PM membranes. As illustrated in Figure 10, equilibration of the N-terminal segment of STXWT in the two membranes results in differential positioning of S14 residue with respect to the STX TM segment in the two compared membranes (Figure 10B,C). Thus, the distance between the Cα carbons of S14 and K263 (Figure 10D) shows that compared to PM membrane, S14 is positioned ∼12 Å closer to K263 in the POPC membrane. This major difference in the positioning of the S14 residue observed in the comparison of STX embedded in POPC and PM membranes is responsible for the different exposure of S14 calculated in the two membranes for reagents representing the CK2 enzyme.

Figure 10.

The N-terminus of STXWT in PM and POPC membranes assumes different positions relative to both the lipid bilayer and the linker region. (A) STXWT in the POPC membrane. Representation is the same as in Figure 8; S14 is shown in space-fill. (B, C) Superposition of STXWT (cartoon) structures in PM (cyan) and POPC (purple) shown in two different views. S14 and K263 residues are highlighted in space-fill representations (K263 is at the interface between the linker and the TM segment). The two structures were superimposed by the backbone atoms of the 246–288 residues. (D) Distance between Cα atoms of S14 and K263 as a function of time plotted for the later parts of the respective trajectories.

Discussion

The computational analysis of the mechanisms underlying the role of PIP2 lipids confirms the working hypothesis that the presence of PIP2 lipids in the membrane affects the ability of STX to become phosphorylated by CK2 enzyme at the S14 position, and supports the general notion that the electrostatic interactions between STX and these lipids can modulate many processes in which the protein is involved at the synapse. These electrostatic interactions were shown here to be critical for the accessibility of S14 for the functionally important phosphorylation of STX by CK2.12−15 Thus, studies based on PIP2-depletion from cell membranes have established that colocalization of STX with PIP2 lipids is a requirement for the STX phosphorylation, and that depletion of PIP2 from cell membranes decreases phosphorylation of STX. In turn, in membranes expressing the dopamine transporter, DAT, this phosphorylation event appears to affect direct STX/DAT interactions (ref (7) and Galli, in preparation) that are important for regulation of AMPH-mediated reverse transport of DA (efflux) through the DAT.7,67,68

By virtue of the atomistic detail, our results show how the modulation by PIP2 lipids is achieved as a direct effect of the interactions on the local structural properties of STX in the juxtamembrane region. Specifically, our inferences about the relation between PIP2 lipid segregation and the spatial organization of the STX N-terminus in general, and of the S14 residue in particular, are substantiated by the results of the simulations. Moreover, these simulations identify the mechanisms by which altered patterns of STX/PIP2 interactions (e.g., due to K2A mutation or PIP2-depletion) result in the type of changes in accessibility of S14 that can modulate the phosphorylation of STX at that site.

The multiscale computational approach that combines elements from the mean-field level coarse-grained representations, with all-atomistic MD simulations, was shown here to be very well suited for the computational prediction of the pattern of PIP2 lipid distribution around STX constructs in the steady state. From these simulations we found that STX in the “closed”-like conformation we modeled can simultaneously attract as many as five PIP2 molecules. Importantly, our results show that the key residues that establish interactions with PIP2 lipids reside not only in the previously identified polybasic KARRKK motif in STX linker region,19−23 but also in the N-terminus stretch as well as in the Habc domain. The PIP2 enrichment we found in the membrane area facing the K55/R150/K181 basic residues from the Habc domain suggests that these residues attract PIP2 lipids that can strongly anchor the Habc domain to the membrane (compare STX positioning in PIP2-enriched vs PIP2-depleted membranes in Figure 9). Moreover, we found that the basic residues in the KARRKK linker motif act synergistically with residues from the N-terminus to attract PIP2 lipids. Thus, the M1/K2/D3 triplet from the N-terminus, together with R261 and K264 from the linker, sequester two PIP2 lipids, whereas the K255/K259/R262 sequence in the linker attracts an additional PIP2 molecule. The participation of M1/K2/D3 residues in the interactions with PIP2 lipids as identified from our study appears to be critical for the conformational properties of the N-terminus region as a whole, and of the S14 residue in particular. This experimentally testable prediction from the computational analysis offers a direct probe of the molecular models and proposed protein–PIP2 interaction mechanisms.

Together, the mechanistic observations from our computational analysis led to the prediction that a K2A mutation in the N-terminus, which causes a remodeling of the STX/PIP2 interactions, would result in a functional phenotype that mimics PIP2-depletion phenotypes. Compared to the wild type construct, this mutation was shown to bring about a new set of interactions between PIP2 and N-terminus, which involves residues R4 and R25 as shown in Figure 7. Because these electrostatic interactions required partial unwinding of the N-terminal helix, we found that the S14 residue was again occluded from the solvent, as in the case of PIP2-depletion. Interestingly, the concomitant lowering of the accessible surface area of the D17 residue that resides in the CK2 enzyme site-recognition motif,12 which appears to be due to strong interactions with S14 in the STXK2A mutant shown in Figure 9, strengthens the prediction that the K2A mutation will have a profound effect on the ability of STX to become phosphorylated at S14 and engage in the DA efflux mechanism.

The computational simulations and mechanistic analyses have thus yielded specific predictions concerning those structural and dynamic elements in STX that can be modulated by electrostatic interactions of STX with PIP2 lipids. Further, the computational control experiments in which disruption of the PIP2 anchoring and interactions was achieved by depleting the membrane of PIP2 (simulations of STXWT in POPC membranes) resulted in equilibration of the N-terminus in a conformation where S14 was closer to both the STX linker region and the membrane, causing a reduction of the S14 exposure to probes that represent large reagents such as the CK2 kinase. This is in agreement with our experimental observations about the reduced phosphorylation in PIP2-depleted membranes compared to PIP2-enriched membranes (Galli, in preparation). The detailed atomistic explanation of the mechanisms enables structure-specific predictions to be drawn from the computational work. These predictions are, therefore, directly testable experimentally by structural modifications, in a manner that can validate the important insights about the mechanistic involvement of PIP2 in the functionally critical phosphorylation of STX.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge insightful discussions with Daniel Harries and Jose Manuel Perez Aguilar. This work was supported by the computational resources of (1) the Institute for Computational Biomedicine at Weill Medical College of Cornell University, (2) the New York Blue Gene Computational Science facility housed at Brookhaven National Lab, and (3) NSF Teragrid allocation MCB090132.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

This work was supported by National Institute of Health Grant 2P01DA012408.

References

- Brunger A. T. (2006) Structure and function of SNARE and SNARE-interacting proteins. Q. Rev. Biophys. 38, 1–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahn R.; Scheller R. H. (2006) SNAREs--engines for membrane fusion. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 7, 631–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth A. M.; Duncan R. R.; Rickman C. (2010) Munc18–1 and syntaxin1: unraveling the interactions between the dynamic duo. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 30, 1309–1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizo J.; Sudhof T. C. (2002) Snares and Munc18 in synaptic vesicle fusion. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3, 641–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein A.; Weber G.; Wahl M. C.; Jahn R. (2009) Helical extension of the neuronal SNARE complex into the membrane. Nature 460, 525–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhardt P.; Hattendorf D. A.; Weis W. I.; Fasshauer D. (2008) Munc18a controls SNARE assembly through its interaction with the syntaxin N-peptide. EMBO J. 27, 923–933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binda F.; Dipace C.; Bowton E.; Robertson S. D.; Lute B. J.; Fog J. U.; Zhang M.; Sen N.; Colbran R. J.; Gnegy M. E.; Gether U.; Javitch J. A.; Erreger K.; Galli A. (2008) Syntaxin 1A interaction with the dopamine transporter promotes amphetamine-induced dopamine efflux. Mol. Pharmacol. 74, 1101–1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervinski M. A.; Foster J. D.; Vaughan R. A. (2010) Syntaxin 1A regulates dopamine transporter activity, phosphorylation and surface expression. Neuroscience 170, 408–416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster J. D.; Cervinski M. A.; Gorentla B. K.; Vaughan R. A. (2006) Regulation of the dopamine transporter by phosphorylation. Handbook Exp. Pharmacol. 197–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung U.; Apparsundaram S.; Galli A.; Kahlig K. M.; Savchenko V.; Schroeter S.; Quick M. W.; Blakely R. D. (2003) A regulated interaction of syntaxin 1A with the antidepressant-sensitive norepinephrine transporter establishes catecholamine clearance capacity. J. Neurosci. 23, 1697–1709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quick M. W. (2003) Regulating the conducting states of a mammalian serotonin transporter. Neuron 40, 537–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickman C., Duncan R. R.. Munc18/Syntaxin interaction kinetics control secretory vesicle dynamics, J. Biol. Chem. 285, 3965-3972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett M. K.; Miller K. G.; Scheller R. H. (1993) Casein kinase II phosphorylates the synaptic vesicle protein p65. J. Neurosci. 13, 1701–1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foletti D. L.; Lin R.; Finley M. A.; Scheller R. H. (2000) Phosphorylated syntaxin 1 is localized to discrete domains along a subset of axons. J. Neurosci. 20, 4535–4544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risinger C.; Bennett M. K. (1999) Differential phosphorylation of syntaxin and synaptosome-associated protein of 25 kDa (SNAP-25) isoforms. J. Neurochem. 72, 614–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartier E., Hamilton P., Matthies H., Javitch J. A., Ulery-Reynolds P. G., and Galli A. (2010) Syntaxin 1 phosphorylation at serine 14 is modulated by amphetamine and regulates functional between DAT and syntaxin 1, 40th Annual Meeting of the Society for Neuroscience, San Diego, California, 2010; Society for Neuroscience Abstract Viewer and Itinerary Planner

- Cartier E., Hamilton P., Karam C., Zhang Y., Gether U., Javitch J., Ulery-Reynolds P. G., Matthies H., and Galli A. (2011) Phosphorylation of the SNARE protein Syntaxin 1 by CK2 regulates AMPH-induced dopamine efflux and behaviors, 41th Annual Meeting of the Society for Neuroscience, Washington, DC, 2011, Society for Neuroscience Abstract Viewer and Itinerary Planner.

- Matthies H., Castillo M. A., Galli A., and Ulery-Reynolds P. G. (2010) Role of syntaxin 1 phosphorylation in neurotransmitter release: Implications for schizophrenia; 40th Annual Meeting of the Society for Neuroscience, San Diego, California, 2010; Society for Neuroscience Abstract Viewer and Itinerary Planner.

- Murray D. H.; Tamm L. K. (2009) Clustering of syntaxin-1A in model membranes is modulated by phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate and cholesterol. Biochemistry 48, 4617–4625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray D. H.; Tamm L. K. (2011) Molecular mechanism of cholesterol- and polyphosphoinositide-mediated syntaxin clustering. Biochemistry 50, 9014–9022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Bogaart G.; Meyenberg K.; Risselada H. J.; Amin H.; Willig K. I.; Hubrich B. E.; Dier M.; Hell S. W.; Grubmuller H.; Diederichsen U.; Jahn R. (2011) Membrane protein sequestering by ionic protein-lipid interactions. Nature 479, 552–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam A. D.; Tryoen-Toth P.; Tsai B.; Vitale N.; Stuenkel E. L. (2008) SNARE-catalyzed fusion events are regulated by Syntaxin1A-lipid interactions. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 485–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kweon D. H.; Kim C. S.; Shin Y. K. (2002) The membrane-dipped neuronal SNARE complex: a site-directed spin labeling electron paramagnetic resonance study. Biochemistry 41, 9264–9268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knecht V.; Grubmuller H. (2003) Mechanical coupling via the membrane fusion SNARE protein syntaxin 1A: a molecular dynamics study. Biophys. J. 84, 1527–1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khelashvili G.; Harries D. (2010) Modelling signalling processes across cellular membranes using a mesoscopic approach. Annu. Rep. Comput. Chem. 6, 236–261. [Google Scholar]

- Khelashvili G.; Weinstein H.; Harries D. (2008) Protein diffusion on charged membranes: a dynamic mean-field model describes time evolution and lipid reorganization. Biophys. J. 94, 2580–2597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khelashvili G.; Harries D.; Weinstein H. (2009) Modeling membrane deformations and lipid demixing upon protein-membrane interaction: the BAR dimer adsorption. Biophys. J. 97, 1626–1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez I.; Ubach J.; Dulubova I.; Zhang X.; Sudhof T. C.; Rizo J. (1998) Three-dimensional structure of an evolutionarily conserved N-terminal domain of syntaxin 1A. Cell 94, 841–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton R. B.; Fasshauer D.; Jahn R.; Brunger A. T. (1998) Crystal structure of a SNARE complex involved in synaptic exocytosis at 2.4 Å resolution. Nature 395, 347–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman J. C.; Robblee J.; Fairman R.; Hughson F. M. (2000) Structural analysis of the neuronal SNARE protein syntaxin-1A. Biochemistry 39, 8470–8479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misura K. M.; Scheller R. H.; Weis W. I. (2001) Self-association of the H3 region of syntaxin 1A. Implications for intermediates in SNARE complex assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 13273–13282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misura K. M.; Gonzalez L. C. Jr.; May A. P.; Scheller R. H.; Weis W. I. (2001) Crystal structure and biophysical properties of a complex between the N-terminal SNARE region of SNAP25 and syntaxin 1a. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 41301–41309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X.; Tomchick D. R.; Kovrigin E.; Arac D.; Machius M.; Sudhof T. C.; Rizo J. (2002) Three-dimensional structure of the complexin/SNARE complex. Neuron 33, 397–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst J. A.; Brunger A. T. (2003) High resolution structure, stability, and synaptotagmin binding of a truncated neuronal SNARE complex. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 8630–8636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pobbati A. V.; Razeto A.; Boddener M.; Becker S.; Fasshauer D. (2004) Structural basis for the inhibitory role of tomosyn in exocytosis. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 47192–47200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kummel D.; Krishnakumar S. S.; Radoff D. T.; Li F.; Giraudo C. G.; Pincet F.; Rothman J. E.; Reinisch K. M. (2011) Complexin cross-links prefusion SNAREs into a zigzag array. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 18, 927–933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu S. H.; Christie M. P.; Saez N. J.; Latham C. F.; Jarrott R.; Lua L. H.; Collins B. M.; Martin J. L. (2011) Possible roles for Munc18–1 domain 3a and Syntaxin1 N-peptide and C-terminal anchor in SNARE complex formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108, 1040–1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu S. H.; Latham C. F.; Gee C. L.; James D. E.; Martin J. L. (2007) Structure of the Munc18c/Syntaxin4 N-peptide complex defines universal features of the N-peptide binding mode of Sec1/Munc18 proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104, 8773–8778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eswar N.; Webb B.; Marti-Renom M. A.; Madhusudhan M. S.; Eramian D.; Shen M. Y.; Pieper U.; Sali A. (2006) Comparative protein structure modeling using Modeller. Curr. Protocol. Protein Sci. Chapter 5, Unit 5.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das R.; Baker D. (2008) Macromolecular modeling with rosetta. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 77, 363–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gracia L. (2005) RMSDTT: RMSD Trajectory Tool, 2.5 ed., Weill Medical College of Cornell University, Department of Physiology and Biophysics. [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey W.; Dalke A.; Schulten K. (1996) VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 14, 33–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andelman D. (1995) Electrostatic Properties of Membranes: the Poisson-Boltzmann Theory, Vol. 1B, Elsevier Science B. V., Amsterdam. [Google Scholar]

- Honig B.; Nicholls A. (1995) Classical electrostatics in biology and chemistry. Science 268, 1144–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harries D.; May S.; Ben-Shaul A. (2003) Curvature and charge modulations in lamellar DNA-lipid complexes. J. Phys. Chem. B 107, 3624–3630. [Google Scholar]

- Harries D.; May S.; Gelbart W. M.; Ben-Shaul A. (1998) Structure, stability, and thermodynamics of lamellar DNA-lipid complexes. Biophys. J. 75, 159–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May S.; Harries D.; Ben-Shaul A. (2000) Lipid demixing and protein-protein interactions in the adsorption of charged proteins on mixed membranes. Biophys. J. 79, 1747–1760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaikin P. M., Lubensky T. C. (2000) Principles of Condensed Matter Physics, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- Jo S.; Lim J. B.; Klauda J. B.; Im W. (2009) CHARMM-GUI Membrane Builder for Mixed Bilayers and Its Application to Yeast Membranes. Biophys. J. 97, 50–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiessling V.; Wan C.; Tamm L. K. (2009) Domain coupling in asymmetric lipid bilayers. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Biomembranes 1788, 64–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips J. C.; Braun R.; Wang W.; Gumbart J.; Tajkhorshid E.; Villa E.; Chipot C.; Skeel R. D.; Kale L.; Schulten K. (2005) Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J. Comput. Chem. 26, 1781–1802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essmann U.; Perera L.; Berkowitz M. L.; Darden T.; Lee H.; Pedersen L. G. (1995) A Smooth Particle Mesh Ewald Method. J. Chem. Phys. 103, 8577–8593. [Google Scholar]

- Mackerell A. D. Jr.; Feig M.; Brooks C. L. 3rd (2004) Extending the treatment of backbone energetics in protein force fields: limitations of gas-phase quantum mechanics in reproducing protein conformational distributions in molecular dynamics simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1400–1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klauda J. B.; Venable R. M.; Freites J. A.; O’Connor J. W.; Tobias D. J.; Mondragon-Ramirez C.; Vorobyov I.; MacKerell A. D.; Pastor R. W. (2010) Update of the CHARMM all-atom additive force field for lipids: Validation on six lipid types. J. Phys. Chem. B 114, 7830–7843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyvonen M. T.; Kovanen P. T. (2003) Molecular Dynamics Simulation of sphingomyelin bilayer. J. Phys. Chem. B 107, 9102–9108. [Google Scholar]

- Lupyan D., Mezei M., Logothetis D. E., Osman R.. A molecular dynamics investigation of lipid bilayer perturbation by PIP2, Biophys. J. 98, 240-247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans D. J.; Holian B. L. (1985) The Nose-Hoover Thermostat. J. Chem. Phys. 83, 4069–4074. [Google Scholar]

- Shi L.; Quick M.; Zhao Y.; Weinstein H.; Javitch J. A. (2008) The mechanism of a neurotransmitter:sodium symporter--inward release of Na+ and substrate is triggered by substrate in a second binding site. Mol. Cell 30, 667–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin S.; Wang J. Y.; Gambhir A.; Murray D. (2002) PIP2 AND proteins: Interactions, organization, and information flow. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 31, 151–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard S. J., Thornton J. M. (1993) “NACCESS” Computer Program, University College London, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. [Google Scholar]

- Lee B.; Richards F. M. (1971) The interpretation of protein structures: estimation of static accessibility. J. Mol. Biol. 55, 379–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visiers I.; Braunheim B. B.; Weinstein H. (2000) Prokink: a protocol for numerical evaluation of helix distortions by proline. Protein Eng. 13, 603–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- http://atlas.physbio.mssm.edu/mezei/simulaid/.

- Khelashvili G.; Grossfield A.; Feller S. E.; Pitman M. C.; Weinstein H. (2009) Structural and dynamic effects of cholesterol at preferred sites of interaction with rhodopsin identified from microsecond length molecular dynamics simulations. Proteins 76, 403–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wriggers W.; Mehler E.; Pitici F.; Weinstein H.; Schulten K. (1998) Structure and dynamics of calmodulin in solution. Biophys. J. 74, 1622–1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin O.; Meggio F.; Marchiori F.; Borin G.; Pinna L. A. (1986) Site specificity of casein kinase-2 (TS) from rat liver cytosol. A study with model peptide substrates. Eur. J. Biochem. 160, 239–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahlig K. M.; Binda F.; Khoshbouei H.; Blakely R. D.; McMahon D. G.; Javitch J. A.; Galli A. (2005) Amphetamine induces dopamine efflux through a dopamine transporter channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102, 3495–3500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoshbouei H.; Sen N.; Guptaroy B.; Johnson L.; Lund D.; Gnegy M. E.; Galli A.; Javitch J. A. (2004) N-terminal phosphorylation of the dopamine transporter is required for amphetamine-induced efflux. PLoS Biol. 2, E78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]