Abstract

Background

Asthma is a common chronic disease with high morbidity. In Uganda, the proportion of asthma in health care facilities and the extent to which asthma management guidelines are followed is unknown.

Objectives

To determine the proportion of adult patients diagnosed with asthma and the proportion of asthma patients that receives recommended asthma therapy prescriptions according to Global Initiative for Asthma with GINA management and prevention guidelines, in the chest clinic and ccident and emergency (A&E) departments in Mulago Hospital.

Methods

A retrospective chart review at Mulago Hospital chest clinic and A&E department from January 1st 2009 to December 31st 2009 was performed. Patients diagnosed with asthma were identified and medications prescribed were recorded. Patients were categorized as having received recommended asthma therapy prescriptions (if therapy was compatible GINA guidelines) or not. Proportions of asthmatics in the two departments and those who received recommended asthma therapy were calculated.

Results

One hundred thirty four (134) of 792 patients in the chest clinic (16.9%) were diagnosed with asthma. At the A&E four hundred and sixteen (416) patients out of 16 800 (2.5%) were diagnosed with asthma. Sixty nine point seven (69.7%) were female. The median age was 29 years (IQR, 19–42). Wheezing was the commonest presenting symptom (55%). Recommended asthma therapy prescriptions were 47.4% for the chest clinic, and 32.2% of the patients at A&E department received asthma therapy prescriptions as recommended for asthma exacerbations management during hospitalization.

Conclusion

Asthma accounts for a significant proportion of outpatients in the chest clinic. The majority of the patients do not receive recommended asthma therapy prescriptions

Introduction

Asthma is one of the leading chronic diseases in the world, with about 300 million people estimated to have the condition1. Though the mortality from asthma has tremendously reduced in developed countries, the morbidity remains high, with an estimated Disability Adjusted Life years lost (DALYS) of 15 million/year and Years of Life lost to disease (YLD) of 2.2%. This is comparable to diabetes, cirrhosis and schizophrenia,2,3,4,5,6,7.

Asthma is defined by the global initiative for asthma management and prevention GINA as a chronic inflammatory disorder of the airways, in which many cells and cellular elements play a role. The chronic inflammation is associated with airway hyper responsiveness that leads to recurrent episodes of wheezing, breathlessness, chest tightness and coughing, particularly at night or in the early morning. These episodes are usually associated with widespread, but variable airflow obstruction within the lung that is often reversible either spontaneously or with treatment. However, the diagnosis of asthma is in most cases a clinical one9. Presence of more than one of the symptoms of wheeze, cough, chest tightness, and breathlessness with variable airway obstruction is usually sufficient to make a diagnosis of asthma9. The specificity of these symptoms and signs is low because they occur in many other conditions9.

Asthma medication if used appropriately leads to reduced asthma morbidity and mortality4. Most international asthma management guidelines recommend that patients initially diagnosed with asthma receive short acting beta2 agonist (SABA), preferably by inhalation, combined with inhaled steroid9. If poor response is noted, the patient should be prescribed a long acting beta2 agonist (LABA), combined with inhaled steroid. Other add-on medications may include leukotriene receptor antagonists, theophyllines or slow release beta2 agonist tablets9. During exacerbations patients should receive systemic steroid, nebulized SABA and oxygen until the patient is stable and then controlled with inhaled beta agonist and steroid9.

Asthma prevalence in eastern Africa is estimated at 4.4%1, most of the asthma medications prescribers do not follow asthma management guidelines in many Low and Medium Income Countries (LMIC)10. No data exist about asthma prevalence, and the extent to which asthma management guidelines are followed in Uganda. Surveys to establish the prevalence of asthma in the community and healthcare facilities are therefore urgently needed. The paucity of data on the extent of following asthma management guidelines also necessitates studies on this matter. This is because factors likely to influence following of the guidelines like high cost of asthma medications compared to patient incomes and inadequate asthma management training are present in Uganda.

In this retrospective chart review we sought to estimate the proportion of asthma patients in the Mulago chest clinic and the accident and emergency (A&E) department, and also establish the proportion of asthma patients that are treated according to GINA guidelines.

Methods

Design and setting

This study was a retrospective chart review conducted at Mulago national referral and teaching hospital's chest clinic and A&E department. Mulago Hospital is a 1 500 bed capacity hospital. It receives referrals from the whole country, as well as neighboring countries in East Africa. In addition to the referrals the hospital acts as a primary care facility for Kampala city with a catchment population of 1 597 900 11 The chest clinic is a specialist outpatient clinic that provides care to patients with respiratory diseases. The majority of patients seen in this clinic are referred from other hospitals or clinics within the hospital.

The A&E department is the portal for all emergencies in the hospital. Most of these are self-referred patients from the surrounding communities.

Data extraction procedure

At the chest clinic a trained research assistant assisted by the chest clinic records officer reviewed the clinic patient's register, to identify new patients who had attended the clinic from January 1st 2009 to December 31st 2009. They identified patients with doctor-diagnosed asthma. The charts of these patients were subsequently retrieved and underwent a chart review.

The chart review was undertaken using a pretested data collection tool. Demographic data, date of registration, and patients residence were recorded. We also collected information about the symptoms the patient reported to the physician on their first day of attending the clinic and the medication that the physician prescribed.

At the A&E department we reviewed the medical emergency register for the total number of patients seen in the same period. We then identified patients with doctor-diagnosed asthma. At the A&E patients' demographics and medication prescribed is all written in a patients' register book. However, symptoms and addresses are not recorded in this book, so these two variables are not available for the A&E patients.

Data analysis

Data were entered in epidata version 3.1 and exported to Stata version 11 for analysis. We calculated the proportion of asthmatics in the chest clinic and A&E department for the study period.

The proportion of patients who were registered in the rainy and dry season was calculated in an attempt to establish seasonality in case presentation. Rainy season in this study included the months of March, April, May, June, September, October and November.. The dry season included the months of December, January, February, July and August.

Patients' residence was classified as urban if they lived in Kampala and Wakiso Districts, and rural if they lived in districts other than these two. Frequencies of the symptoms of chest pain, wheeze, cough, and shortness of breath as well as medications prescribed were analyzed. Medication prescriptions were categorized as either recommended or not (recommended if compatible with GINA asthma management guidelines and not if incompatible the same guidelines) 9. At the chest clinic, patients whose prescription included an inhaled steroid and beta2 agonist were presumed to have received recommended therapy and their proportion was determined. We assumed that all patients in the chest clinic did not have acute severe asthma.

In the A&E department recommended therapy was defined as patients whose treatment included nebulised beta2 agonist, systemic steroid, and oxygen. We did not collect data on medications prescribed at discharge.

Results

Proportion of asthma

Chest clinic: From January 1st 2009 through December 31st 2009 792 new patients were registered at the chest clinic. One hundred and thirty four (16.9%) had doctor-diagnosed asthma. A&E department: During the same period 416 patients who attended the A&E department had asthma out of the total department attendance of 16 800 patients (2.5%).

Social demographics and seasonality

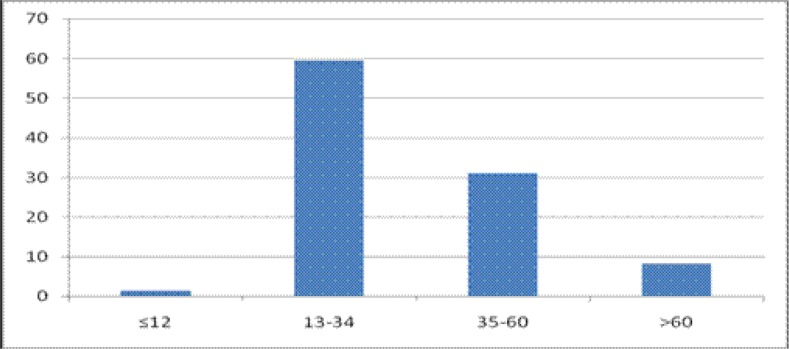

Eighty three percent (83%) of the patients were from the urban areas. Females constituted 69.7% of the patients. The median age was 29 years (range, 19–42). The youngest patient seen at the emergency department was one year and the oldest was 85 years. The distribution of the patients in the different age groups and by month of registration is shown figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1.

Distribution of asthma patients in the different age groups

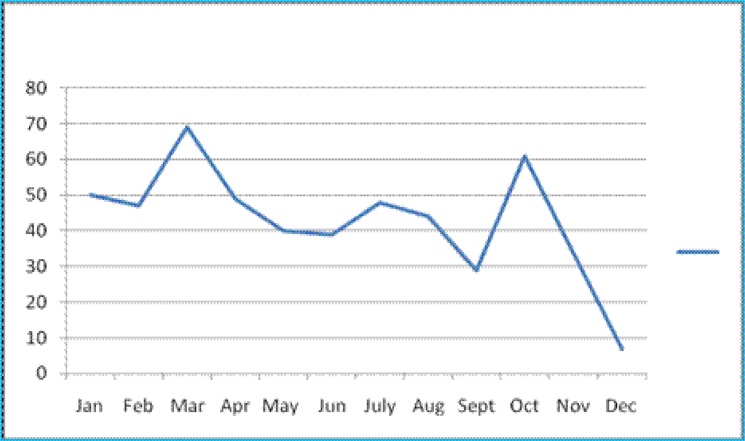

Figure 2.

Monthly asthma patient registration at the chest clinic and emergency department

Overall, there was no significant difference in the number of patients registered in the rainy season as compared to the dry season, 48.7% (95% CI 46.9–55.6%) for the rainy season versus 51.3% (95% CI 44.4–.53.1%) for the dry season. We however found that there were significantly more patients presenting in the rainy season at the chest clinic than at the emergency department (p=0.009).

Presenting symptoms

The commonest presenting asthma symptom was wheezing reported by 55% of the patients. The rest of the symptoms are shown in table 1

Table 1.

Asthma symptoms among asthma patients at the chest clinic

| Symptom | No of patients |

Percentage (%) |

| Wheezing | 44 | 55.0 |

| Cough | 43 | 53.8 |

| Shortness of breath | 43 | 53.8 |

| Chest pain | 18 | 22.5 |

Medication prescription

Sixty four patients (47.4%) in the chest clinic received GINA recommended therapy according to asthma management guidelines At the A&E department, 97 (23.2%) were treated according to the GINA guidelines. More than 50% of the patients at both clinics received antibiotics, that is 70/134 (51.6%) and 278/416 (66.8%) for the chest and A&E respectively). The different asthma medications prescribed are shown in table 2

Table 2.

Asthma medications prescription at the chest clinic and the A & E departments

| Medications | Department | |

| Chest clinic | A&E | |

| % (N=134) | department % (N=416) |

|

| Oral Salbutamol | 52.6 | 42.9 |

| Oral Prednisolone | 64.2 | 44.4 |

| Oral Aminophyline | 15.8 | 12.9 |

| Intravenous Aminophyline | 1.1 | 72.4 |

| Antibiotics | 51.6 | 66.8 |

| Inhaled beta2 agonist | 37.9 | 11.5 |

| Inhaled steroid | 24.2 | 2.4 |

| Nebulised beta2 agonist | 5.3 | 20.7 |

| Nebulised Beta2 agonist with oxygen |

0 | 2.4 |

Discussion

In Mulago hospital we have found the proportion of doctor-diagnosed asthma to be 16.9% in the chest clinic and 2.5 % in the A&E department. This prevalence is comparable to that in other tertiary health care facilities in Africa14,15. We found that 83% of the patients were from Kampala city.

Most of the patients were in the 13–34 age group and up to 70% were female. This is consistent with findings by Gustavo JR and others in an asthma study in Spain and Latin America which found that 37.5% of the patients were in the 15–35 age group and 72% were female19. The commonest asthma symptom was wheezing as has been found in other studies 22.

Generally, appropriate asthma treatment was low, both at the chest clinic and A&E department but it was worse at the emergency department. For example, over 50% of the patients received oral salbutamol therapy instead of inhaled salbutamol. The main reason may be cost , because inhaled steroid and beta2 agonist are more expensive than oral steroids and beta2 agonist. Cost has been recognized as a factor in asthma medication use in many developing countries. Bobby Ramakant wrote in Citizens News Service on World Health Day 2009 that the cost a combination of inhaler is higher than the monthly salary of a nurse25.In the emergency department only 20.7% of the patients were nebulised and only 2.4% received nebulisation with oxygen despite the fact that nebulisation equipment and oxygen are available in the department most of the time. This finding could be due to lack of awareness on the part of the attending health workers. Studies done in some countries in Africa have shown that prescribers do not follow asthma guidelines 26. On the other hand in developed countries use of asthma guidelines has improved; by 2006 inhaled steroids use was 89% as compared to 62% in 199527,28

The finding of more than half of the patients receiving an antibiotic prescription is more than twice that reported in other studies. In the United States a study found that 22% of the acute asthma was treated with an antibiotic35. Current guidelines do not recommend an antibiotic for asthma unless there is evidence of bacterial infection36. A systematic review evaluating the efficacy of antibiotics in acute asthma failed to show its benefit. The high antibiotic prescription in our setting is driven by lack of knowledge concerning asthma management guidelines. Clinicians interpret the cough that the patients present with as being a bacterial infection and therefore prescribe an antibiotic.

We acknowledge that our study has limitations. Firstly, it was a retrospective analysis. We could not find some of the data in the patients file. This mainly affected the symptoms data while all data on medications was available. Secondly we used doctor diagnosed asthma in this study. It is possible some patients with asthma may have not been given a diagnosis of asthma and vice versa. Lastly this study was carried out in a tertiary health care facility and therefore these results cannot be representative of what is happening at the population level.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that asthma accounts for a significant proportion of outpatients in the chest clinic. The poor adherence to international asthma management guidelines necessitates the urgent need of asthma management training in Mulago Hospital. Local asthma management protocols should be developed and displayed at all points where asthma patients are seen in the hospital. Prospective studies to establish the burden of asthma in the hospital and in the community, as well as discharge medications, are also needed.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the staff of the Mulago Hospital chest clinic and the A&E department. We thank Mulago Hospital Management for allowing us to access the records. We acknowledge the contribution of Dr Joseph and Mr. Okot Gabriel for conducting the chart review. Our thanks also go to Mr. Yusufu Mulumba for assisting with the data analysis.

References

- 1.Masoli M, Fabian D, Holt S, Beasley R. Global Burden of Asthma report. 2004 doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2004.00526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization, author. The global burden of disease: 2004 update. Geneva: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jarvis D, Burney P. Epidemiology of asthma. In: Holgate S, Busse W, editors. Asthma and Rhinitis. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Press; 1995. pp. 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murray CJL, Lopez AD. Global mortality, disability, and the contribution of risk factors: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 1997;349:1436–1442. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07495-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ait-Khaled N, Enarson D, Bousquet J. Chronic respiratory diseases in developing countries: the burden and strategies for prevention and management. Bull WHO. 2001;79:971–979. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization, author. WHO consultation on the development of a comprehensive approach for the prevention and control of chronic respiratory diseases. Geneva: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization, author. Global health risks: mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks. Geneva: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mpairwe H, Muhangi L, Ndibazza J, Tumusiime J, Muwanga M, Rodrigues LC, et al. Skin prick test reactivity to common allergens among women in Entebbe, Uganda. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008;102(4):367–373. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Global Initiative for Asthma, author. Global Strategy for asthma management and prevention 2010 (update) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mugusi F, Edwards R, Hayes L, Unwin N, Mbanya JC, Whiting D, et al. Prevalence of wheeze and self-reported asthma and asthma care in an urban and rural area of Tanzania and Cameroon. Trop Doct. 2004;34(4):209–214. doi: 10.1177/004947550403400408. http://www.citypopulation.de/Uganda.html. Retrieved 2011-02-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) Steering Committee, author. Worldwide variations in the prevalence of asthma symptoms: International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) Eur Respir J. 1998;12 doi: 10.1183/09031936.98.12020315. 315±335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ait-Khaled N, Odhiambo J, Pearce N, Adjoh KS, Maesano IA, Benhabyles B, et al. Prevalence of symptoms of asthma, rhinitis and eczema in 13- to 14-year-old children in Africa: the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood Phase III. Allergy. 2007;62(3):247–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wasunna AE. Asthma as seen at the casualty department, Kenyatta National Hospital, Nairobi. East Afr Med J. 1968;45(11):701–705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Desalu OO, Oluwafemi JA, Ojo O. Respiratory diseases morbidity and mortality among adults attending a tertiary hospital in Nigeria. J Bras Pneumol. 2009;35(8):745–752. doi: 10.1590/s1806-37132009000800005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burney P. The changing prevalence of asthma? Thorax. 2002;57(Suppl II):ii36–ii39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Niekerk CH, Weinberg EG, Shore SC, De V Heese H, Van Schalkwyk DJ. Prevalence of asthma: a comparative study of urban and rural Xhosa children. Clinical Allergy. 1979;9:319–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1979.tb02489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Odhiambo JA, Ng'ang'a LW, Mungai MW, Gicheha CM, Nyamwaya JK, Karimi F, et al. Urban-rural differences in questionnaire-derived markers of asthma in Kenyan school children. Eur Respir J. 1998;12:1105–1112. doi: 10.1183/09031936.98.12051105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rodrigo Gustavo Javier, Plaza Vicente, Bellido-Casado Jesús, Neffen Hugo, Bazús María Teresa, Levy Gur, et al. The study of severe asthma in Latin America and Spain (1994-2004): characteristics of patients hospitalized with acute severe asthma. J bras Pneumol. 2009;35(7):635–644. doi: 10.1590/s1806-37132009000700004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.European Community Respiratory Health Survey, author. Variations in the prevalence of respiratory symptoms, self-reported asthma attacks, and use of asthma medication in the European Community Respiratory Health Survey (ECRHS) Eur Respir J. 1996;9:687–695. doi: 10.1183/09031936.96.09040687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Melgert BN, Ray A, Hylkema MN, Timens W, Postma DS. Are there reasons why adult asthma is more common in females. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2007;7:143–150. doi: 10.1007/s11882-007-0012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Becklake MR, Kauffmann F. Gender differences in airway behavior over the human life span. Thorax. 1999;54:1119–1138. doi: 10.1136/thx.54.12.1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schatz M, Camargo CA., Jr The relationship of sex to asthma prevalence, health care utilization, and medications in a large managed care organization. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;91:553–555. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61533-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) Steering Committee, author. Worldwide variation in prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and atopic eczema: ISAAC. Lancet. 1998;351:1225–1232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramakant Bobby. World Asthma Day (5 May 2009) Asthma control is appalling in most countries. Feature Article Citizen News Service (CNS) Sun. 2009 May 03; [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aït-Khaled N, Enarson DA, Bencharif N, Boulahdib F, et al. Implementation of asthma guidelines in health centres of several developing countries. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006;10(1):104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodriguez de la Vega Adolf, Tejeiro FernLndez Arnaldo, G6mez Echeverria Armando, et al. Investigation of the prevalence and inheritance of bronchial asthma in San Antonio De Los Baros, Cuba. Paho Bulletin. 1975;ix:3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salmeron S, Liard R, Elkharrat D, Muir J, Neukirch F, Ellrodt A. Asthma severity and adequacy of management in accident and emergency departments in France: a prospective study. Lancet. 2001;358(9282):629–635. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(01)05779-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuo E, Kesten S. A retrospective comparative study of in-hospital management of acute severe asthma: 1984 vs 1989. Chest. 1993;103(6):1655–1661. doi: 10.1378/chest.103.6.1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liou A, et al. Causative and contributive factors to asthma severity and patterns of medication use in patients seeking specialized asthma care. Chest. 2003;124:1781–1788. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.5.1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fukutomi Y, Taniguchi M, Tsuburai T, Okada C, Shimoda T, Onaka A, et al. Survey of asthma control and anti-asthma medication use among Japanese adult patients. Arerugi. 2010;59(1):37–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alavy B, Chung V, Maggiore D, Shim C, Dhuper S. Emergency department as the main source of asthma care. J Asthma. 2006 Sep;43(7):527–532. doi: 10.1080/02770900600857069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bouayad Z, Aichane A, Afif A, Benouhoud N, Trombati N, Chan-Yeung M, et al. Prevalence and trend of self-reported asthma and other allergic disease symptoms in Morocco: ISAAC phase I and III. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006 Apr;10(4):371–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnston NW, Sears MR. Asthma exacerbations epidemiology. Thorax. 2006;61(8):722–728. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.045161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vanderweil Stefan G, Tsai Chu-Lin, Pelletier Andrea J, et al. Inappropriate Use of Antibiotics for Acute Asthma in United States Emergency Departments. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2008;15:736–743. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, author. National Asthma Education and Prevention Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health. NIH Publication 08-4051; [May 20,2008]. http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/asthma/asthgdln.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 36.British Thoracic Society, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines network, author. British Guidelines on Management of Asthma, a national clinical guideline. 2008. May, (revised June 2009) [Google Scholar]