Abstract

Axonal branches from a subset of neurons in cerebral cortical layer 6 innervate both cortical layer 4 and the thalamus. As such, these neurons are poised to modulate thalamocortical transmission at multiple forebrain sites. Here, we examined the functional organization of the layer 6 intracortical projections in auditory, somatosensory and visual cortical areas using an optogenetic approach to specifically target these neurons. We characterized the anatomical and physiological organization of these projections using laser-scanning photostimulation to functionally map the elicited postsynaptic responses in layer 4. We found that these responses originated from regions over 1 mm in width, eliciting short-term facilitating responses. These results indicate that intracortical modulation of layer 4 occurs via widespread layer 6 projections in each sensory cortical area.

Keywords: cortex, thalamus, layer 6, layer 4, optogenetics, cre-lox recombination, auditory, somatosensory, visual

Introduction

In the cerebral cortex, a subset of cerebral cortical layer 6 neurons sends branched projections to the thalamus and cortical layer 4 [1–4]. Anatomically, the layer 6 to layer 4 projections are particularly robust, contributing ~30% of the synapses onto a layer 4 neuron [5]. Physiologically, these projections in both the cortex and thalamus elicit responses showing paired pulse facilitation and, if at a high enough level, activate metabotropic glutamate receptors [1,6–9]. Due to their potential roles in modulating cortical and thalamic activity [6,8,10], we sought to specifically study the functional organization of these layer 6 projections in the sensory cortical areas of the mouse using an optogenetic approach based on Cre-Lox recombination [11].

An adenoassociated virus, inserted with a `floxed' construct containing the fused sequence of channelrhodopsin and YFP (ChR-YFP), was transfected in various cortical areas (auditory, somatosensory, visual) of B6.Cg-Tg(Ntsr1-cre)GN220Gsat/Mmcd mice, which express Cre-recombinase only in these layer 6 intracortical and corticothalamic projection neurons. We characterized the anatomical patterns of the layer 6 ChR-YFP expressing fibers in each cortical area injected. We then assayed the functional topography and short-term synaptic properties of the layer 6 projections using laser-scanning photostimulation to specifically activate ChR-YFP expressing fibers. In general, we found that these layer 6 fibers arborize profusely in layer 4 and thalamus. Moreover, photostimulation of layer 6 fibers expressing ChR-YFP elicited a broad pattern of convergent excitation in layer 4, supporting a potential role for widespread subgranular modulation of layer 4 thalamorecipient neurons.

Materials and Methods

Surgery and injections

Adult mice (B6.Cg-Tg(Ntsr1-cre)GN220Gsat/Mmcd) (MMRC-U.C. Davis, Davis, CA) expressing Cre-recombinase in intracortical and corticothalamic projection neurons of layer 6 were used in these experiments. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. To anesthetize the animal, an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (100–120 mg/kg) and xylazine (5–10 mg/kg) was given and deemed sufficient when no responses were elicited to strong toe pinches. The animal was then placed into a stereotactic device (Stoelting, Wood Dale, IL) and a craniotomy performed above the injection sites. A pAAV-Ef1a-double floxed-hChR2(H134R)-EYFP-WPRE-pA vector (200 μl) (UNC Vector Core, Chapel Hill, NC) was pressure injected using a Nanoliter injector (Drummond Scientific, Broomall, PA) into either the primary auditory (A1: n=4), somatosensory (S1: n=4), or visual (V1: n=4) cortices. The craniotomy site was covered and the injection site sutured with non-absorbable monofilament nylon. An injection of buprenorphine (0.05–0.1mg/kg) was given for post-operative analgesia. Following recovery and a 14–21 day survival to allow adequate expression and transport of ChR2-YFP, the animals were sacrificed and the brain removed and processed using the techniques for slice preparation described below.

Slice preparation and recording

After deeply anesthetizing the animals with isofluorane followed by decapitation, the brains were submerged in cool, oxygenated, artificial cerebral spinal fluid (ACSF: 125 mM NaCl, 25 mM HCO3, 3 mM KCl, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 1 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2, and 25 mM glucose). Whole brains were then blocked coronally and affixed to a vibratome stage to collect 500 μm thick sections, which were placed in a holding chamber containing physiological ACSF to recover for 1 h at 32°C, then returned to room temperature for the remainder of the experiment.

A recording chamber perfused with ACSF was used for whole cell recordings of the slice preparation under DIC optics using recording pipettes with tip resistances of 4–8 MΩ filled with intracellular solution (135mM KGluconate, 7mM NaCl, 10mM HEPES, 1–2mM Na2ATP, 0.3mM GTP, 2mM MgCl2 at a pH of 7.3 obtained with KOH and osmolality of 290 mosm obtained with distilled water). This solution results in ~10mV junction potentials that is uncorrected for in voltage measurements. Current or voltage clamp recordings were made using the Axoclamp 2A amplifier and pCLAMP software (Axon Instruments). The acquired data was digitized using a Digidata 1200 board and then stored in a computer for later analysis.

Laser-Scanning Photostimulation

Laser-scanning photostimulation was used to activate ChR-YFP labeled fibers using an average beam intensity of 5 mW to give a 1-ms, 100-pulse light stimulus by Q-switching the pulsed UV laser (355 nm wavelength, frequency-tripled Nd: YVO4, 100- kHz pulse repetition rate; DPSS Lasers, Inc., Santa Clara, CA). Responses were analyzed using custom software written in Matlab (MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA), and the traces were superimposed on a photomicrograph corresponding to the stimulation sites, as previously described [3,8,12].

Histology

Following physiological recordings, the acute slices were fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde/30% sucrose and then re-sectioned at 40 μm using a freezing microtome. The sections were mounted on gelatinized slides and confocal images were acquired with a 3I Marianas Yokogawa-type spinning disk confocal microscope.

Results

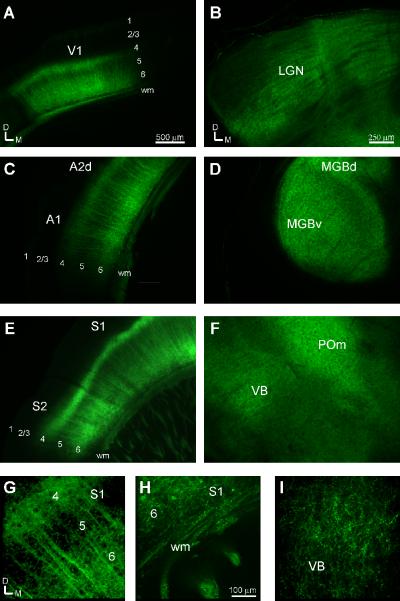

In the Cre-transgenic mice (B6.Cg-Tg(Ntsr1-cre)GN220Gsat/Mmcd) that we transfected with the `floxed' ChR-YFP construct, robust expression of ChR-YFP was observed in layer 6 neuronal cell bodies and in dense fibers that terminated in layer 4 and thalamic nuclei corresponding to the cortical areas injected (Fig. 1). Thus, labeling in the visual (V1: Fig 1A), auditory (A1: Fig. 1C), and somatosensory (S1: Fig. 1E) areas corresponded with labeling in modality appropriate thalamic nuclei, i.e. lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN: Fig. 1B), medial geniculate body (MGB: Fig. 1D), and the ventrobasal and posterior medial nuclei (VB and POm: Fig. 1F). Apical dendrites and axonal fibers originating in layer 6 cell bodies coursed through layer 5, ramifying sparsely, and terminated robustly in layer 4 (Fig. 1G). More rarely, labeled apical fibers traversed and arborized in upper layer 1, being slightly more prevalent in the primary visual cortex. Corticothalamic axons traversed from the layer 6 neuronal cell bodies through the white matter (Fig. 1H), before arborizing profusely in the thalamus, terminating in small boutons (Fig. 1I).

Figure 1.

ChR-YFP expression in layer 6 corticothalamic neurons in the visual (A, B), auditory (C, D) and somatosensory (E–I) cortices and thalamic nuclei. Neuronal cell bodies in layer 6 project to layer 4 (A, C, E, G) and the thalamus (B, D, F, I), arborize broadly and terminate in small boutons. A1, primary auditory cortex; A2d, dorsoposterior auditory area; ChR-YFP: channelrhosopsin conjugated to YFP; D, dorsal; LGN, lateral genicuate nucleus; M, medial; MGBv, ventral division of the medial geniculate body; S1, primary somatosensory cortex; S2, secondary somatosensory area; V1, primary visual cortex; POm, posterior medial nucleus, wm, white matter; 1–6, cortical layers 1–6

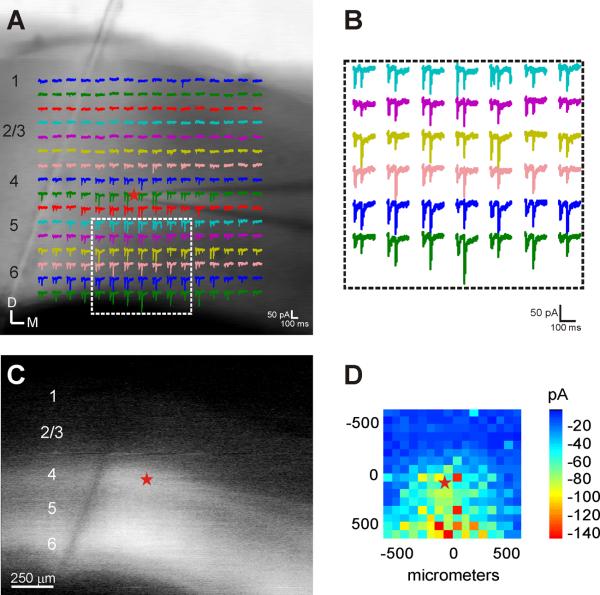

In order to examine the physiological properties of these ChR-YFP labeled projections, whole-cell slice recordings from neurons in layer 4 and the thalamus were obtained in response to paired-pulse photostimulation (50ms ISI) of these ChR-YFP labeled fibers. The elicited EPSCs in both layer 4 and the thalamus generally facilitated in response to repetitive photostimulation (Fig. 2), similar to previous results that used electrical stimulation methods [1,6,9,13,14]. In addition, layer 4 neurons were excited by photostimulation across a broad area (Fig. 2), suggesting a high degree of convergence of layer 6 inputs. Laser-scanning photostimulation only elicited facilitating responses from regions where labeled fibers were primarily present, i.e. layers 4–6 (Fig. 2A, C). The most robust responses, based on the amplitude of the first EPSC, were found within a narrow column (~200 μm) beneath the recorded neuron, however prominent responses could be elicited across the entire span of the stimulation map (~1.3 mm), putatively encompassing several cortical columns.

Figure 2.

Repetitive photostimulation elicits robust, facilitating EPSCs in layer 4 neurons across broad regions of layers 4–6. (A) Overlay of stimulation sites and current responses on acute slice photomicrograph. (B) Expanded traces from boxed region in (A). (C) ChR-YFP expression in the acute slice preparation. (D) Mean amplitude of elicited first EPSCs. ChR-YFP, channelrhosopsin conjugated to YFP; D, dorsal; EPSCs, excitatory postsynaptic currents; M, medial

Discussion

Our results expand upon previous studies that suggest that layer 6 plays a modulatory role in sensory information processing by regulating the efficacy of thalamocortical transmission [1,6,9,10,13–16]. Our findings here indicate that layer 6 can potentially modulate layer 4 neurons across an extensive cortical domain greater than 1 mm in width. The breadth of these layer 6 inputs to layer 4 revealed using our optogenetic approach contrasts with those obtained using laser-scanning photostimulation via uncaging of glutamate, which instead reveal highly focal regions of layer 6 projections [8,17–21]. We posit that the maps obtained via uncaging of glutamate could potentially underestimate the breadth of these relatively weak inputs from layer 6, due to inadequate recruitment of neurons sufficient to elicit detectable responses in layer 4. Conversely, our optogenetic approach may overestimate the breadth of these connections, as stimulation of axon collaterals could antidromically elicits responses from neurons far from the stimulation site. As such, the breadth of the functional layer 6 intracortical projections is likely broader than previously indicated, but presumably less than the upper boundary established here.

Conclusion

Our results indicate substantial convergence of facilitating synaptic inputs from layer 6 to layer 4 using an optogenetic approach to specifically target this defined population of cortical neurons. Although this in vitro characterization of synaptic properties is invaluable for dissecting the functional topography of neuronal circuitry, the application of this cell-type specific optogenetic approach in vivo enables the specific examination of the role of these layer 6 neurons on receptive fields and behavior [10]. The advent of the methods employed here should thus continue to reveal unexpected functional relationships among otherwise obfuscated or intractable neuronal circuits.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Vytas Byndokas for his valuable assistance with the confocal microscope and image acquisition. This work was supported by NIH/NIDCD grant R03 DC 011361, SVM CORP grant LAV3202, and NSF-LA EPSCoR grant PFUND276 (CCL) and NIH/NIDCD grant R01 DC 008794 (SMS).

Footnotes

The authors report no conflict of interest

References

- [1].Stratford KJ, Tarczy-Hornoch K, Martin KA, Bannister NJ, Jack JJ. Excitatory synaptic inputs to spiny stellate cells in cat visual cortex. Nature. 1996;382:258–261. doi: 10.1038/382258a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Thomson AM. Neocortical layer 6, a review. Front Neuroanat. 2010;4:13. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2010.00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lam YW, Sherman SM. Functional organization of the somatosensory cortical layer 6 feedback to the thalamus. Cereb Cortex. 2010;20:13–24. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Lee CC. Thalamic and cortical pathways supporting auditory processing. Brain Lang. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2012.05.004. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Binzegger T, Douglas R, Martin K. A quantitative map of the circuit of cat primary visual cortex. J Neurosci. 2004;24:8441–8453. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1400-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Reichova I, Sherman SM. Somatosensory corticothalamic projections: distinguishing drivers from modulators. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92:2185–2197. doi: 10.1152/jn.00322.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Cruikshank SJ, Urabe H, Nurmikko AV, Connors BW. Pathway-specific feedforward circuits between thalamus and neocortex revealed by selective optical stimulation of axons. Neuron. 2010;65:230–245. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Lee CC, Sherman SM. Modulator property of the intrinsic cortical projections from layer 6 to layer 4. Front Syst Neurosci. 2009;3:3. doi: 10.3389/neuro.06.003.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Tarczy Hornoch K, Martin KAC, Stratford KJ, Jack JJB. Intracortical excitation of spiny neurons in layer 4 of cat striate cortex in vitro. Cereb Cortex. 1999;9:833–843. doi: 10.1093/cercor/9.8.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Olsen SR, Bortone DS, Adesnik H, Scanziani M. Gain control by layer six in cortical circuits of vision. Nature. 2012;483:47–52. doi: 10.1038/nature10835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Tye KM, Deisseroth K. Optogenetic investigation of neural circuits underlying brain disease in animal models. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:251–266. doi: 10.1038/nrn3171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Lee CC, Sherman SM. Intrinsic modulators of auditory thalamocortical transmission. Hear Res. 2012;287:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Bartlett EL, Smith PH. Effects of paired-pulse and repetitive stimulation on neurons in the rat medial geniculate body. Neuroscience. 2002;113:957–974. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00240-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lee CC, Sherman SM. Synaptic properties of thalamic and intracortical intputs to layer 4 of the first- and higher-order cortical areas in the auditory and somatosensory systems. J Neurophysiol. 2008;100:317–326. doi: 10.1152/jn.90391.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Llano DA, Sherman SM. Evidence for non-reciprocal organization of the mouse auditory thalamocortical-corticothalamic projections systems. J Comp Neurol. 2008;507:1209–1227. doi: 10.1002/cne.21602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Lee CC, Sherman SM. Glutamatergic inhibition in sensory neocortex. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19:2281–2289. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Oviedo HV, Bureau I, Svoboda K, Zador AM. The functional asymmetry of auditory cortex is reflected in the organization of local cortical circuits. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:1413–1420. doi: 10.1038/nn.2659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Barbour DL, Callaway EM. Excitatory local connections of superficial neurons in rat auditory cortex. J Neurosci. 2008;28:11174–11185. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2093-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Hooks BM, Hires SA, Zhang YX, Huber D, Petreanu L, Svoboda K, et al. Laminar analysis of excitatory local circuits in vibrissal motor and sensory cortical areas. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1000572. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Yoshimura Y, Dantzker JL, Callaway EM. Excitatory cortical neurons form fine-scale functional networks. Nature. 2005;433:868–873. doi: 10.1038/nature03252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Callaway EM. Cell type specificity of local cortical connections. J Neurocytol. 2002;31:231–237. doi: 10.1023/a:1024165824469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]