Abstract

Despite the benefit of adjuvant hormonal therapy (HT) on mortality among women with breast cancer (BC), many women are non-adherent with its use. We investigated the effects of early discontinuation and non-adherence to HT on mortality in women enrolled in Kaiser Permanente of Northern California (KPNC). We identified women diagnosed with hormone-sensitive stage I–III BC, 1996–2007, and used automated pharmacy records to identify prescriptions and dates of refill. We categorized patients as having discontinued HT early if 180 days elapsed from the prior prescription. For those who continued, we categorized patients as adherent if the medication possession ratio was ≥80%. We used Cox proportional hazards models to estimate the association between discontinuation and non-adherence with all-cause mortality. Among 8,769 women who filled at least one prescription for HT, 2,761 (31%) discontinued therapy. Of those who continued HT, 1,684 (28%) were non-adherent. During a median follow-up of 4.4 years, 813 women died. Estimated survival at 10 years was 80.7% for women who continued HT versus 73.6% for those who discontinued (P < 0.001). Of those who continued, survival at 10 years was 81.7 and 77.8% in women who adhered and non-adhered, respectively (P < 0.001). Adjusting for clinical and demographic variables, both early discontinuation (HR 1.26, 95% CI 1.09–1.46) and non-adherence (HR 1.49, 95% CI 1.23–1.81), among those who continued, were independent predictors of mortality. Both early discontinuation and non-adherence to HT were common and associated with increased mortality. Interventions to improve continuation of and adherence to HT may be critical to improve BC survival.

Keywords: Hormonal therapy, Adherence, Survival

Introduction

Adjuvant hormonal therapy (HT) for hormone-sensitive breast cancer (BC) has been one of the most important additions to the treatment of BC, resulting in impressive reductions in the BC recurrence and mortality rates [1, 2]. These oral therapies include either tamoxifen and/or an aromatase inhibitor and are typically prescribed for 5 years or longer. Surprisingly, despite the dramatic efficacy of hormonal agents, there is increasing evidence that the early discontinuation and non-adherence rates for both tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors are high and often unrecognized [3-10]. For example, among women with non-metastatic BC who were enrolled in Kaiser Permanente of Northern California (KPNC), by 4.5 years, 32% of women discontinued HT, and of those who continued, only 72% were fully adherent, despite being enrolled in a health care plan with pharmacy benefits [11].

While it is increasingly apparent that non-adherence is a significant problem, much less is known about the impact of discontinuation of HT on survival. In the Oxford overview analysis that evaluated several trials of different duration, patients treated with 3 or 5 years of tamoxifen compared to 1 year had better survival outcomes [12, 13]. The benefits of a 5-year duration of HT treatment were definitively established from a randomized trial conducted by the Swedish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group that compared 2 versus 5 years of tamoxifen therapy. The overall survival benefit for 5 years of prescribed therapy versus 1 or 2 years was 18% [14]. Adherence to therapy in this trial, however, was not reported. Outside the clinical trial setting, several small observational studies suggest that early discontinuation of hormone therapy is associated with increased mortality; however, these studies were small, single institution and/or had limited follow-up for survival [9, 15, 16].

To provide an understanding of the relationship between early discontinuation and non-adherence with all-cause mortality, we evaluated women over a 10-year period who were enrolled in a large, pre-paid integrated health system, KPNC. The KPNC population is large, diverse in race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status, representative of all age groups, and participants all have a prescription health plan and access to health care.

Methods

Data source

Kaiser Permanente of Northern California is a pre-paid, integrated health plan that provides medical services to more than 3 million members over 14 counties in Northern California. This population is racially diverse and very similar to the socioeconomic makeup of the area it serves [17].

The Patient Demographic Database of KPNC contains key demographic characteristics of KPNC enrollees, including their medical record number, date of birth, gender, and specific member characteristics. Socioeconomic status of patients’ neighborhood of residence was estimated by geocoding patients’ addresses, assigning a census tract code, linking the data to Census 2000 information on education, poverty, income, and housing costs to derive a composite score; each patient was assigned a neighborhood SES quintile based on the distribution of the composite index across California census tracts [18]. KPNC also maintains a cancer registry that reports to the regional registries comprising the NCI-supported Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program.

The Pharmacy Information Management System records each ordered and filled prescription at all KPNC outpatient and inpatient pharmacies. This database contains cost, prescribing practitioner, and medication information, including the name, National Drug Code, date of prescription, and date of refill.

The Outpatient Summary Clinical Record contains information on all outpatient encounters at KPNC hospitals, medical centers, and medical offices. Procedure codes are based on Common Procedure Terminology (CPT) and diagnosis codes are based on the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), with an additional KPNC-specific code to provide further detail.

Sample selection

We identified all women in the KPNC database who were diagnosed with pathology-confirmed stage I–III BC between January 1, 1996 and June 30, 2007. We restricted our sample to patients who were classified as having tumors that were positive for estrogen and/or progesterone receptor, and who received at least one prescription for oral HT (tamoxifen, anastrozole, exemestane, or letrozole) within 12 months of diagnosis and prior to the diagnosis of recurrent disease.

Study covariates

Socio-demographic variables

Age at diagnosis was categorized into <50, 50–65, and >65 years. Marital status at the time of diagnosis was categorized as married or not married. Race was classified as white, black, Asian, and Hispanic. We generated an aggregate SES score from education, poverty and income data from census data, following the method adapted by Du et al. [19] Patients were ranked on a 1–5 scale, where 1 was the lowest value, based on a formula incorporating these variables that were weighted equally.

Comorbid disease

The Klabunde adaptation of the Charlson comorbidity index, which is a weighted score of comorbidity, was constructed by searching for ICD-9-CM (International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision, Clinical Modification) diagnostic codes in the KPNC inpatient and outpatient claims [20, 21].

Tumor characteristics

We categorized tumor size as <1, 1–2, >2 cm, or unknown; tumor grade as low (1 or 2), high (3 or 4), or unknown; lymph node status as positive, negative, or unknown.

Breast cancer treatment

We categorized surgical treatment as mastectomy, lumpectomy, or no/unknown. Patients were also dichotomized according to whether or not they had received adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation therapy, respectively. Types of HT were categorized as tamoxifen only, aromatase inhibitor (AI) only, or both.

Prescription refill interval

Prescription refill was categorized into 30-, 60-, and 90-day intervals. Patients were placed in each prescription refill category based on the most common prescription interval determined during their follow-up period.

Discontinuation and non-adherence

We categorized patients as having discontinued therapy if 180 days elapsed from the prior prescription without a refill prior to the completion of 4.5 years of therapy. Of those who continued, we categorized patients as being adherent if the ratio of total days covered by the medication divided by the days needing the medication, i.e., the medication possession ratio (MPR), was greater than or equal to 80%, a definition commonly used in the adherence literature [22, 23].

In order to determine the total days covered by the medication, the number of pills for each prescription was estimated from the date of the first prescription to the date of the subsequent prescription, which fell into 30-, 60-, and 90-day intervals. We assumed that patients could refill prescriptions 7 days earlier for a 60-day prescription, and 14 days earlier for a 90-day prescription. Therefore, if the interval between two prescriptions was ≤53 days, we assumed the interval supplied by the first prescription was 30 days. If the interval was >53 and <76 days, the assumed interval was 60 days, and if the interval was ≥76 days, the assumed interval was 90 days. The total number of days covered by the medication was then determined by adding all the intervals between prescriptions plus an additional 30, 60, or 90 days for the last prescription based on prior interval pattern.

To determine the days needing the medication, we censored a patient at the date of death, the date dis-enrolled from KPNC, the date of recurrence based on metastatic ICD-9 codes (196.x; 197.x; or 198.x), new claims for chemotherapy administration, or after 4.5 years elapsed from the date of first prescription due to uncertainties with regard to intent of refills in the last 6 months. The total days needing the medication was then counted from the date of the first prescription to the date of censoring.

Outcome variable

The main outcome measure was all-cause mortality.

Statistical analysis

Survival analyses were performed using the Kaplan-Meier method, and the differences between groups with regard to survival time were evaluated by the log rank test. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to estimate the association between discontinuation or non-adherence to HT (i.e., MPR ≥ 80%) with all-cause mortality, controlling for socio-demographic and clinical variables. To assess the impact of adherence levels on survival, the Cox proportional hazard models were also used to estimate the association between different levels of non-adherence (MPR < 90%, MPR < 70%, MPR < 60%) with all-cause mortality. All analyses were conducted using SAS, Version 9.13.

Results

We identified 8,769 women who filled at least one prescription for either an AI or tamoxifen within 12 months of their BC diagnosis and prior to the diagnosis of recurrent disease. Of these, 3,802 (43%) received only tamoxifen, while 2,313 (29%) received only an AI, while 2,654 (30%) received both types of hormone at least once during the study period. Among the 8,769 women, 2,761 (31.5%) discontinued therapy early. Of the 6,008 patients who continued therapy to the end of 4.5 years, 1,684 (28%) were non-adherent (19% of total). Only 49% of patients took HT for the full duration at the optimal schedule [11].

The baseline demographic and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. Median age at diagnosis was 62 years. Women in the group that continued therapy were more likely to be married, to receive chemotherapy, refilled their medications every 60 or 90 days (vs. 30 days), and took both tamoxifen and an AI at least once during the study period. Women who discontinued therapy were more likely to be older. Women who adhered to HT were more likely to be married and refilled their medications every 60 or 90 days (vs. 30 days) than women who were non-adherent.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients diagnosed with hormone-receptor-positive breast cancer, stages I–III, who received adjuvant endocrine therapy, KPNC, 1996–2007

| Characteristics | All patients (8769) |

Patients continued therapy (6008) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients discontinued (2761) |

% 31.5 | No. of patients continued (6008) |

% 68.5 | No. of patients non-adhered (1684) |

% 28 | No. of patients adhered (4324) |

% 72 | |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | ||||||||

| <50 | 472 | 17.1 | 1000 | 16.6 | 287 | 17.0 | 713 | 16.5 |

| 50–64 | 1015 | 36.8 | 2594 | 43.2 | 691 | 41.0 | 1903 | 44.0 |

| ≥65 | 1274 | 46.1 | 2414 | 40.2 | 706 | 42.0 | 1708 | 39.5 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||

| White | 2145 | 77.7 | 4542 | 75.6 | 1246 | 74.0 | 3296 | 76.2 |

| Black | 162 | 5.9 | 326 | 5.4 | 110 | 6.5 | 216 | 5.0 |

| Hispanic | 180 | 6.5 | 450 | 7.5 | 137 | 8.1 | 313 | 7.3 |

| Asian | 274 | 9.9 | 690 | 11.5 | 191 | 11.3 | 499 | 11.6 |

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Unmarried | 1242 | 45.0 | 2283 | 38.0 | 709 | 42.1 | 1574 | 36.4 |

| Married | 1519 | 55.0 | 3725 | 62.0 | 975 | 57.9 | 2750 | 63.9 |

| Socioeconomic status | ||||||||

| Lowest quintile | 388 | 14.1 | 741 | 12.4 | 239 | 14.2 | 502 | 11.6 |

| 2nd quintile | 644 | 23.3 | 1436 | 24.0 | 392 | 23.3 | 1054 | 24.4 |

| 3rd quintile | 596 | 21.6 | 1388 | 23.2 | 392 | 23.3 | 1005 | 23.2 |

| 4th quintile | 553 | 20.0 | 1105 | 18.5 | 293 | 17.5 | 816 | 18.9 |

| Highest quintile | 580 | 21.0 | 1315 | 21.9 | 368 | 21.8 | 947 | 21.9 |

| Comorbidity score | ||||||||

| 0 | 2477 | 89.7 | 5529 | 93.1 | 1553 | 92.2 | 4039 | 93.4 |

| 1 | 184 | 6.67 | 269 | 4.5 | 79 | 4.7 | 190 | 4.4 |

| ≥2 | 100 | 3.62 | 147 | 2.4 | 52 | 3.1 | 95 | 2.2 |

| Tumor size (cm) | ||||||||

| 0–<1 | 808 | 29.0 | 1572 | 26.2 | 417 | 24.8 | 1155 | 26.7 |

| 1–2 | 1263 | 45.3 | 2682 | 44.6 | 732 | 43.5 | 1950 | 45.1 |

| >2 | 587 | 21.0 | 1389 | 23.1 | 416 | 24.7 | 973 | 22.5 |

| Unknown | 132 | 4.7 | 365 | 6.1 | 119 | 7.1 | 246 | 5.7 |

| Tumor grade | ||||||||

| Low (1 or 2) | 2012 | 72.9 | 4298 | 71.5 | 1195 | 71.0 | 3103 | 71.8 |

| High (3 or 4) | 429 | 15.5 | 1046 | 17.4 | 295 | 17.5 | 751 | 17.4 |

| Unknown | 320 | 11.6 | 664 | 11.1 | 194 | 11.5 | 4770 | 10.9 |

| Lymph node involvement | ||||||||

| Positive | 179 | 6.5 | 625 | 10.4 | 187 | 11.2 | 438 | 10.1 |

| Negative | 2279 | 82.5 | 4963 | 82.6 | 1373 | 81.5 | 3590 | 83.0 |

| Unknown | 303 | 11.0 | 420 | 7.0 | 124 | 7.4 | 296 | 6.9 |

| Surgery | ||||||||

| Mastectomy | 959 | 34.7 | 2231 | 37.1 | 622 | 36.7 | 1609 | 37.2 |

| Lumpectomy | 1746 | 63.2 | 3661 | 61.0 | 1024 | 61.1 | 2637 | 61.0 |

| No/unknown | 56 | 2.0 | 116 | 1.9 | 38 | 2.2 | 78 | 1.8 |

| Chemotherapy | ||||||||

| No/unknown | 2164 | 78.4 | 4251 | 70.8 | 1186 | 70.4 | 3065 | 70.9 |

| Yes | 597 | 21.6 | 1757 | 29.2 | 498 | 29.6 | 1259 | 29.1 |

| Radiation | ||||||||

| No/unknown | 1440 | 52.2 | 3182 | 53.0 | 910 | 54.0 | 2272 | 52.5 |

| Yes | 1321 | 47.8 | 2826 | 47.0 | 774 | 46.0 | 2052 | 47.5 |

| Prescription refill interval | ||||||||

| 30 days | 908 | 32.9 | 856 | 14.3 | 406 | 24.1 | 450 | 10.4 |

| 60 days | 378 | 13.7 | 945 | 15.7 | 177 | 10.5 | 768 | 17.8 |

| 90 days | 1475 | 53.4 | 4207 | 70.0 | 1101 | 65.4 | 3106 | 71.8 |

| Types of endocrine therapy | ||||||||

| Tamoxifen only | 1448 | 52.3 | 2354 | 39.2 | 704 | 41.8 | 1650 | 38.1 |

| AI only | 651 | 23.6 | 1662 | 27.7 | 475 | 28.2 | 1187 | 27.5 |

| Both | 662 | 24.1 | 1992 | 33.2 | 505 | 30.0 | 1487 | 34.4 |

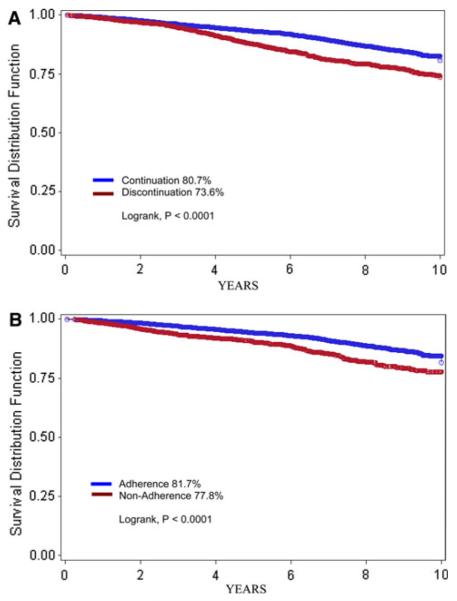

Patients were followed up to 10 years, with a median follow-up of 4.4 years. A total of 813 deaths were recorded. Unadjusted Kaplan–Meier curves comparing patients who continued therapy to those who discontinued, and patients who were adherent to those who were non-adherent are shown in Fig. 1. The estimate of survival at 10 years was 80.7% in women who continued therapy, and 73.6% in those who discontinued early (log rank, P < 0.001). Of those who continued, survival at 10 years was 81.7 and 77.8% in women who did and did not adhere to HT, respectively (log rank, P < 0.001).

Fig. 1.

a Kaplan-Meier curve comparing continuation and discontinuation of hormonal therapy among 8,769 patients with stage I–III hormone-receptor-positive breast cancer who initiated treatment, KPNC, 1996-2007. b Kaplan-Meier curve comparing adherence and non-adherence to hormonal therapy among 5,979 patients with stage I–III hormone-receptor-positive breast cancer who continued treatment, KPNC, 1996–2007

We performed Cox proportional hazards analysis to examine the association between HT discontinuation or non-adherence with all-cause mortality, controlling for socio-demographic and clinical variables (Table 2). Both early discontinuation (HR 1.26, 95% CI 1.09–1.46) and non-adherence (HR 1.49, 95% CI 1.23–1.81) among those who continued were significant independent predictors of mortality. Compared to women who refilled every 30 days, those who refilled every 90 days had improved survival (HR 0.70, 95% CI 0.55-0.88). Women who were married, with the highest SES score, no lymph node involvement, and who received radiation therapy had improved overall survival. Hispanics and Asians also had improved survival compared with Caucasians. Adjusting for all factors, older age, increasing comorbidities, larger tumor size, higher tumor grade, and no/unknown surgery (vs. mastectomy) increased the risk of death.

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis of discontinuation/non-adherence to hormonal therapy and all-cause mortality among women diagnosed with stage I–III hormone-receptor-positive breast cancer who initiated adjuvant hormonal therapy KPNC, 1996–2007

| Characteristics | All patients (8769) |

Patients continued therapy (6008) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multivariate HRa discontinuation |

95% CI | Multivariate HR non-adherence |

95% CI | |

| Continuation | 1.00 | – | – | – |

| Discontinuation | 1.26 | 1.09–1.46 | – | – |

| Adherent | – | – | 1.00 | – |

| Non-adherent | – | – | 1.49 | 1.23–1.81 |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | ||||

| <50 | 0.92 | 0.66–1.30 | 0.85 | 0.55–1.32 |

| 50–64 | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – |

| ≥65 | 3.06 | 2.51–3.72 | 2.72 | 2.13–3.47 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – |

| Black | 0.82 | 0.61–1.12 | 0.74 | 0.50–1.10 |

| Hispanic | 0.70 | 0.50–0.96 | 0.50 | 0.32–0.79 |

| Asian | 0.62 | 0.45–0.87 | 0.49 | 0.31–0.77 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Unmarried | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – |

| Married | 0.78 | 0.67–0.90 | 0.82 | 0.68–0.99 |

| Socioeconomic status | ||||

| Lowest quintile | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – |

| 2nd quintile | 0.73 | 0.57–0.92 | 0.71 | 0.52–0.97 |

| 3rd quintile | 0.82 | 0.65–1.04 | 0.89 | 0.66–1.20 |

| 4th quintile | 0.93 | 0.74–1.16 | 0.89 | 0.60–1.21 |

| Highest quintile | 0.77 | 0.61–0.98 | 0.64 | 0.47–0.88 |

| Comorbidity score | ||||

| 0 | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – |

| 1 | 2.37 | 1.95–2.89 | 2.16 | 1.62–1.87 |

| ≥2 | 3.60 | 2.79–4.66 | 3.60 | 2.55–5.08 |

| Tumor size (cm) | ||||

| 0–1 | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – |

| 1–2 | 1.31 | 1.08–1.58 | 1.36 | 1.06–1.76 |

| >2 | 1.98 | 1.60–2.44 | 2.03 | 1.53–2.70 |

| Unknown | 1.22 | 0.88–1.70 | 1.21 | 0.79–1.86 |

| Tumor grade | ||||

| Low (1 or 2) | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – |

| High (3 or 4) | 1.52 | 1.27–1.81 | 1.69 | 1.35–2.13 |

| Unknown | 0.85 | 0.69–1.05 | 0.84 | 0.64–1.12 |

| Lymph node involvement | ||||

| Positive | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – |

| Negative | 0.59 | 0.45–0.77 | 0.59 | 0.42–0.82 |

| Unknown | 1.34 | 0.98–1.82 | 1.61 | 1.10–2.35 |

| Surgery | ||||

| Mastectomy | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – |

| Lumpectomy | 1.08 | 0.88–1.36 | 1.18 | 0.90–1.54 |

| No/unknown | 2.06 | 1.43–2.97 | 1.81 | 1.10–3.00 |

| Chemotherapy | ||||

| No | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – |

| Yes | 0.86 | 0.67–1.08 | 0.83 | 0.62–1.12 |

| Radiation | ||||

| No | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – |

| Yes | 0.66 | 0.55–0.86 | 0.64 | 0.50–0.83 |

| Prescription refill interval | ||||

| 30 days | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – |

| 60 days | 0.73 | 0.60–0.89 | 0.70 | 0.55–0.89 |

| 90 days | 0.66 | 0.56–0.78 | 0.65 | 0.52–0.82 |

| Types of endocrine therapy | ||||

| Tam only | 1.00 | – | 1.00 | – |

| AI only | 1.07 | 0.85–1.36 | 1.25 | 0.91–1.71 |

| Both | 0.94 | 0.79–1.15 | 0.99 | 0.79–1.23 |

HR hazard ratio Missing data were characterized as unknown

All variables in the multivariate analysis were adjusted for each other

Since age, tumor size, and lymph node involvement were strong determinants of outcomes, we performed subgroup analyses stratifying patients according to age (<65 vs. ≥65 years) or stage (tumor size > 2 cm with positive lymph node vs. others). The associations between discontinuation or non-adherence to HT with all-cause mortality did not differ between these subgroups. We also examined these associations excluding prescription refill interval as a covariate since it was a strong predictor of both continuation and adherence to therapy, and the main results did not change.

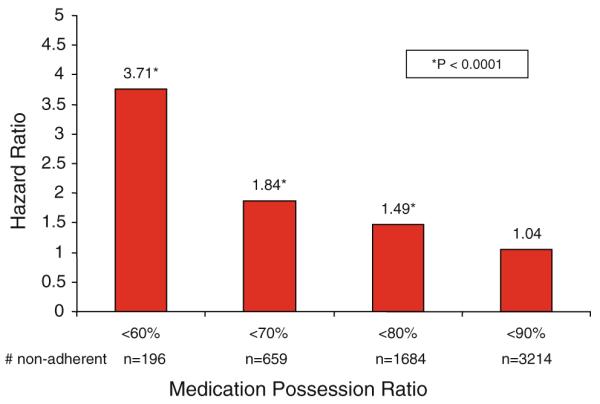

Separate multivariate analyses were repeated to determine the association between levels of adherence with all-cause mortality by varying the definition of non-adherence (MPR <90% vs. ≥90%; MPR<80% vs. ≥80%; MPR<70% vs. ≥70%; or MPR <60% vs. ≥60%). There was no difference with full adherence versus MPR <90%. However, once the MPR was below 80%, we found that decreasing levels of adherence was associated with increased risk of death (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Association between degree of adherence and all-cause mortality among 5,979 patients who continued adjuvant hormonal treatment, KPNC. 1996–2007. Results based on individual multivariate analysis compared to the rest of the cohort, controlling for clinical and socio-demographic variables

Discussion

Much of cancer research has focused on discovering and proving the efficacy of new interventions to reduce cancer mortality. However, even in settings where proven efficacious treatments exist, it is disappointing to learn that many patients do not receive these treatments or there are aberrations in its administration. In this large, population-based study of women with early-stage BC enrolled in KPNC, as we previously reported, only 49% of patients were fully adherent with HT for the 4.5-year follow-up period [11]. We now report that this early discontinuation of HT was associated with a 26% increase in all-cause mortality, and, of those who continued, non-adherence was associated with a 49% increase in all-cause mortality. In addition, compared to 100% adherence, mortality rates increased with decreasing levels of adherence.

The relationship between dose-intensity and outcome has been established for adjuvant BC chemotherapy. Bonadonna and colleagues [24-27] demonstrated that the benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy was limited to patients who received ≥85% of the optimal dose, while patients who received less treatment than that fared no better than those who received none. Work by our group and others has shown that these types of aberrations in chemotherapy treatment quality are common, and have an impact on mortality [28, 29]. For example, our group found that among women with BC who initiated adjuvant chemotherapy, 28% discontinued treatment early and that the earlier they terminated treatment, the higher their mortality hazard ratio was compared to those who completed treatment [28]. Similar results were found for patients with colon [30] and ovarian [31] cancer as well.

With regard to oral cancer therapies, much less is known. We previously reported that, in the same KPNC cohort of women with non-metastatic hormone-sensitive BC treated with adjuvant oral HT, 32% of the women discontinued HT early, and of those who continued, only 72% were fully adherent. Younger or older age and an increased number of comorbidities were associated with earlier discontinuation, while Asian race, being married, and longer prescription refill interval were associated with completion of therapy [11]. Several other investigators have reported rates of non-adherence to HT ranging from 30 to 50% [5, 7, 10, 32, 33]. A similar lack of adherence occurs with oral medications, such as Gleevec, for gastrointestinal stromal tumors or chronic myelogenous leukemia [34, 35]. Given the increasing number of new oral cancer treatments, the identification of ways to increase adherence may reduce cancer mortality. Understanding and specifically addressing the reasons for discontinuation will help to increase adherence and ultimately improve outcomes.

Our results confirm the findings from several smaller observational studies that suggested that HT discontinuation is associated with increased mortality [9, 15, 16]. A study by Yood et al. [15] showed, in a sample of 886 elderly women treated with tamoxifen, that those who were exposed to 5 years of therapy had a sixfold higher BC survival than those treated for less than 1 year. Similarly, in a retrospective study of 1,633 women, adherence <80% was associated with slightly poorer survival (hazard ratio = 1.10) [9]. While many of the randomized trials did not report adherence, recent data on discontinuation of therapy are reported to be 10–28% depending on the length of follow-up [36-38]. Despite this, there is little data on adherence or on the relationship between discontinuation and survival.

We were reassured that the cut-off of 80% MPR, which is somewhat arbitrary and not well justified in the literature [23], represented a cut-off that corresponded to survival outcome. While increasing levels of non-adherence were less common, they were associated with increased mortality risk. Interestingly, classifying the 1,534 patients who were non-adherent 80–90% of the time into the non-adherent category removed the detrimental effect on mortality, suggesting non-adherence above 80% may not result in adverse clinical consequences.

Although we also found that early discontinuation and lack of adherence to HT were associated with poor survival, we cannot assume that this association is causal. Some patients may be at high risk for adverse outcomes due to the same factors that cause them to discontinue treatment early: poor physical condition, performance status, psychological outlook, or health behaviors. In addition, some patients may have discontinued treatment early in response to toxicity. Treatment-associated toxicities are often a major barrier to the full application of effective cancer treatment. For example, in a survey of 622 postmenopausal women, 30% discontinued HT, and 84% did so because of side effects [39].

There are several limitations to our study. First, we were not able to determine the reasons for non-adherence and discontinuation, which may also be associated with the increased risk of mortality, nor were we able to evaluate BC-specific mortality. Another limitation may be the inability to capture all recurrences with electronic medical data; however, the methods used have been validated in other studies [40]. While assumptions were made to calculate total number of pills dispensed on average, which may have resulted in an under or overestimation of the number of pills dispensed, the method for using prescription claims data for estimation of adherence has been validated in prior studies [41].

We found that both early discontinuation and non-adherence with HT in women with early-stage BC are associated with increased all-cause mortality. Further investigation is critical to identify interventions to help such patients comply with the full course of adjuvant HT. Such interventions have the potential to have an impact on BC survival.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Hershman is the recipient of a grant from the American Cancer Society (RSGT-08-009-01-CPHPS). Dr. Kushi is the recipient of a grant from the National Cancer Institute (R01 CA105274). Dr. Gomez is the recipient of a grant from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Rapid Response Surveillance Study under contracts N01-PC-35136. Dr. Neugut is the recipient of a grant from the Department of Defense (BC043120).

Contributor Information

Dawn L. Hershman, Department of Medicine and the Herbert Irving Comprehensive Cancer Center, College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University Medical Center, 161 Fort Washington Avenue, 10-1068, New York, NY 10032, USA; Departments of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA; New York Presbyterian Hospital, New York, NY, USA

Theresa Shao, Department of Medicine and the Herbert Irving Comprehensive Cancer Center, College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University Medical Center, 161 Fort Washington Avenue, 10-1068, New York, NY 10032, USA.

Lawrence H. Kushi, Division of Research, Kaiser-Permanente of Northern California, Oakland, CA, USA

Donna Buono, Departments of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA.

Wei Yann Tsai, Departments of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA.

Louis Fehrenbacher, Division of Research, Kaiser-Permanente of Northern California, Oakland, CA, USA.

Marilyn Kwan, Division of Research, Kaiser-Permanente of Northern California, Oakland, CA, USA.

Scarlett Lin Gomez, Greater Bay Area Cancer Registry, Cancer Prevention Institute of California (CPIC), Fremont, CA, USA.

Alfred I. Neugut, Department of Medicine and the Herbert Irving Comprehensive Cancer Center, College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University Medical Center, 161 Fort Washington Avenue, 10-1068, New York, NY 10032, USA; Departments of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA; New York Presbyterian Hospital, New York, NY, USA

References

- 1.Winer EP, Hudis C, Burstein HJ, Wolff AC, Pritchard KI, Ingle JN, Chlebowski RT, Gelber R, Edge SB, Gralow J, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology technology assessment on the use of aromatase inhibitors as adjuvant therapy for post-menopausal women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer: status report 2004. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(3):619–629. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 2005;365(9472):1687–1717. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66544-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kimmick G, Anderson R, Camacho F, Bhosle M, Hwang W, Balkrishnan R. Adjuvant hormonal therapy use among insured, low-income women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(21):3445–3451. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.2419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ziller V, Kalder M, Albert US, Holzhauer W, Ziller M, Wagner U, Hadji P. Adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy in postmenopausal women with breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2009;20(3):431–436. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Partridge AH, LaFountain A, Mayer E, Taylor BS, Winer E, Asnis-Alibozek A. Adherence to initial adjuvant anastrozole therapy among women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(4):556–562. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.5451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chlebowski RT, Geller ML. Adherence to endocrine therapy for breast cancer. Oncology. 2006;71(1-2):1–9. doi: 10.1159/000100444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lash TL, Fox MP, Westrup JL, Fink AK, Silliman RA. Adherence to tamoxifen over the five-year course. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;99(2):215–220. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9193-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Partridge AH, Avorn J, Wang PS, Winer EP. Adherence to therapy with oral antineoplastic agents. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(9):652–661. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.9.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCowan C, Shearer J, Donnan PT, Dewar JA, Crilly M, Thompson AM, Fahey TP. Cohort study examining tamoxifen adherence and its relationship to mortality in women with breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2008;99(11):1763–1768. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barron TI, Connolly R, Bennett K, Feely J, Kennedy MJ. Early discontinuation of tamoxifen: a lesson for oncologists. Cancer. 2007;109(5):832–839. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hershman DL, Kushi LH, Shao T, Buono D, Kershenbaum A, Tsai WY, Fehrenbacher L, Gomez SL, Miles S, Neugut AI. Early discontinuation and nonadherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy in a cohort of 8,769 early-stage breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2010 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.9655. doi:10.1200/JCO.2009.25.9655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group Systemic treatment of early breast cancer by hormonal, cytotoxic, or immune therapy. 133 randomised trials involving 31,000 recurrences and 24,000 deaths among 75,000 women. Lancet. 339(8785):71–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bryant J, Fisher B, Dignam J. Duration of adjuvant tamoxifen therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2001;(30):56–61. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a003462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swedish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group Randomized trial of two versus five years of adjuvant tamoxifen for postmenopausal early stage breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 88(21):1543–1549. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.21.1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yood MU, Owusu C, Buist DS, Geiger AM, Field TS, Thwin SS, Lash TL, Prout MN, Wei F, Quinn VP, et al. Mortality impact of less-than-standard therapy in older breast cancer patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206(1):66–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Geiger AM, Thwin SS, Lash TL, Buist DS, Prout MN, Wei F, Field TS, Ulcickas Yood M, Frost FJ, Enger SM, et al. Recurrences and second primary breast cancers in older women with initial early-stage disease. Cancer. 2007;109(5):966–974. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krieger N. Data resources of the Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Program in northern California. Oakland, California: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yost K, Perkins C, Cohen R, Morris C, Wright W. Socioeconomic status and breast cancer incidence in California for different race/ethnic groups. Cancer Causes Control. 2001;12(8):703–711. doi: 10.1023/a:1011240019516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Du XL, Fang S, Vernon SW, El-Serag H, Shih YT, Davila J, Rasmus ML. Racial disparities and socioeconomic status in association with survival in a large population-based cohort of elderly patients with colon cancer. Cancer. 2007;110(3):660–669. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klabunde CN, Warren JL, Legler JM. Assessing comorbidity using claims data: an overview. Med Care. 2002;40(8 Suppl):IV-26–35. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200208001-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karve S, Cleves MA, Helm M, Hudson TJ, West DS, Martin BC. Good and poor adherence: optimal cut-point for adherence measures using administrative claims data. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25(9):2303–2310. doi: 10.1185/03007990903126833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(5):487–497. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bonadonna G, Valagussa P, Moliterni A, Zambetti M, Brambilla C. Adjuvant cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil in node-positive breast cancer: the results of 20 years of follow-up. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(14):901–906. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199504063321401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wood WC, Budman DR, Korzun AH, Cooper MR, Younger J, Hart RD, Moore A, Ellerton JA, Norton L, Ferree CR, et al. Dose and dose intensity of adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II, node-positive breast carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(18):1253–1259. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199405053301801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hryniuk W. Importance of chemotherapy scheduling: pieces of the puzzle. Cancer Investig. 1999;17(7):545–546. doi: 10.3109/07357909909032864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Budman DR, Berry DA, Cirrincione CT, Henderson IC, Wood WC, Weiss RB, Ferree CR, Muss HB, Green MR, Norton L, et al. Dose and dose intensity as determinants of outcome in the adjuvant treatment of breast cancer. The Cancer and Leukemia Group B. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90(16):1205–1211. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.16.1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hershman D, McBride R, Jacobson JS, Lamerato L, Roberts K, Grann VR, Neugut AI. Racial disparities in treatment and survival among women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(27):6639–6646. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.12.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Griggs JJ, Sorbero ME, Stark AT, Heininger SE, Dick AW. Racial disparity in the dose and dose intensity of breast cancer adjuvant chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2003;81(1):21–31. doi: 10.1023/A:1025481505537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neugut AI, Matasar M, Wang X, McBride R, Jacobson JS, Tsai WY, Grann VR, Hershman DL. Duration of adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer and survival among the elderly. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(15):2368–2375. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.5005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wright J, Doan T, McBride R, Jacobson J, Hershman D. Variability in chemotherapy delivery for elderly women with advanced stage ovarian cancer and its impact on survival. Br J Cancer. 2008;98(7):1197–1203. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Partridge AH, Wang PS, Winer EP, Avorn J. Nonadherence to adjuvant tamoxifen therapy in women with primary breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(4):602–606. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.07.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bramwell VH, Pritchard KI, Tu D, Tonkin K, Vachhrajani H, Vandenberg TA, Robert J, Arnold A, O’Reilly SE, Graham B, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled study of tamoxifen after adjuvant chemotherapy in premenopausal women with early breast cancer (National Cancer Institute of Canada—Clinical Trials Group Trial, MA.12) Ann Oncol. 2010;21(2):283–290. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Noens L, van Lierde MA, De Bock R, Verhoef G, Zachee P, Berneman Z, Martiat P, Mineur P, Van Eygen K, MacDonald K, et al. Prevalence, determinants, and outcomes of nonadherence to imatinib therapy in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia: the ADAGIO study. Blood. 2009;113(22):5401–5411. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-196543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Darkow T, Henk HJ, Thomas SK, Feng W, Baladi JF, Goldberg GA, Hatfield A, Cortes J. Treatment interruptions and nonadherence with imatinib and associated healthcare costs: a retrospective analysis among managed care patients with chronic myelogenous leukaemia. Pharmacoeconomics. 2007;25(6):481–496. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200725060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goss PE, Ingle JN, Martino S, Robert NJ, Muss HB, Piccart MJ, Castiglione M, Tu D, Shepherd LE, Pritchard KI, et al. A randomized trial of letrozole in postmenopausal women after five years of tamoxifen therapy for early-stage breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(19):1793–1802. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coombes RC, Hall E, Gibson LJ, Paridaens R, Jassem J, Delozier T, Jones SE, Alvarez I, Bertelli G, Ortmann O, et al. A randomized trial of exemestane after two to three years of tamoxifen therapy in postmenopausal women with primary breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(11):1081–1092. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Howell A, Cuzick J, Baum M, Buzdar A, Dowsett M, Forbes JF, Hoctin-Boes G, Houghton J, Locker GY, Tobias JS. Results of the ATAC (Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination) trial after completion of 5 years’ adjuvant treatment for breast cancer. Lancet. 2005;365(9453):60–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17666-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Salgado B, Zivian M. Aromatase inhibitors: side effects reported by 622 women. Breast Cancer Res Treat; San Antonio breast cancer symposium: 2007; 2007; p. S168. abstract 3131. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Earle CC, Nattinger AB, Potosky AL, Lang K, Mallick R, Berger M, Warren JL. Identifying cancer relapse using SEER-Medicare data. Med Care. 2002;40(8 Suppl):IV-75–81. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200208001-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grymonpre R, Cheang M, Fraser M, Metge C, Sitar DS. Validity of a prescription claims database to estimate medication adherence in older persons. Med Care. 2006;44(5):471–477. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000207817.32496.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]