Abstract

The New York City (NYC) Health Department has implemented a comprehensive tobacco control plan since 2002, and there was a 27% decline in adult smoking prevalence in NYC from 2002 to 2008. There are conflicting reports in the literature on whether residual smoker populations have a larger or smaller share of “hardcore” smokers. Changes in daily consumption and daily and nondaily smoking prevalence, common components used to define hardcore smokers, were evaluated in the context of the smoking prevalence decline. Using the NYC Community Health Survey, an annual random digit dial, cross-sectional survey that samples approximately 10,000 adults, the prevalence of current heavy daily, light daily, and nondaily smokers among NYC adults was compared between 2002 and 2008. A five-level categorical cigarettes per day (CPD) variable was also used to compare the population of smokers between the 2 years. From 2002 to 2008, significant declines were seen in the prevalence of daily smoking, heavy daily smoking, and nondaily smoking. Among daily smokers, there is also evidence of population declines in all but the lowest smoking category (one to five CPD). The mean CPD among daily smokers declined significantly, from 14.6 to 12.5. After an overall decline in smoking since 2002, the remaining smokers may be less nicotine dependent, based on changes in daily consumption and daily and nondaily smoking prevalence. These findings suggest the need to increase media and cessation efforts targeted towards lighter smokers.

Keywords: Smoking prevalence, Cigarette consumption, Tobacco control

Introduction

Since 2002, the New York City (NYC) Department of Health and Mental Hygiene has implemented a comprehensive tobacco control plan consisting of taxation, legislation, education, cessation, and evaluation.1 There was a 27 % decline in adult smoking prevalence in NYC between 2002 and 2008, from 21.5 to 15.8 %. Evaluating changes in the prevalence of daily smoking and cigarettes per day (CPD) can assess whether the declines were primarily concentrated among heavy or light smokers.

There are conflicting reports in the literature on whether, following smoking prevalence declines, the residual smoker population is comprised of more “hardcore” smokers, i.e., those with the greatest difficulty quitting or, on the contrary, smokers who are less addicted.2,3 Some research shows that smokers who do not quit are likely to be more nicotine dependent, which is known as the hardening hypothesis.4,5 Goodwin et al. reported that the prevalence of adult lifetime smoking in the USA declined across four recent birth cohorts, but nicotine dependence increased.6 One explanation for the hardening hypothesis is that the increased social pressures against smoking may disproportionately affect casual smokers, resulting in a greater likelihood of cessation in this population, leaving more severe smokers.7,8 Contrary evidence suggests that the proportion of hardcore smokers does not necessarily increase as smoking prevalence declines.2 Following smoking prevalence declines, national data show a decrease in CPD and an increase in the time to the first cigarette of the day, indicating that residual smokers are less dependent.5

Previous population-based studies have focused on national or international samples, which differ in demographic makeup from diverse, urban settings.4,6,8 This analysis provides more recent local-level data from NYC to evaluate changes in CPD and daily and nondaily smoking prevalence, commonly used to define hardcore smokers.9 There are limitations in defining hardcore smokers using only these measures as these smokers are typically classified by a combination of smoking behaviors including quit attempts, quit intention, nicotine dependence, and smoking duration.2,8 However, reductions in smoking consumption have been shown to be associated with declines in nicotine dependence and nondaily smokers are generally less nicotine dependent.10,11

To assess whether cigarette consumption has declined among the remaining smokers in NYC, changes in daily and nondaily smoking prevalence and CPD among daily smokers were evaluated between 2002 and 2008. Data in support of hardening would show a smaller decline in the prevalence of heavy daily smoking among all adults as compared to light daily and nondaily smoking. In contrast, steeper declines among heavier smokers would suggest a “softening” of the remaining smoker population.

Methods

NYC data were evaluated using the 2002 and 2008 NYC Community Health Surveys (CHS).1,12 The NYC CHS is a random digit dial, cross-sectional survey of approximately 10,000 NYC adults aged 18 and over, sampled within 34 neighborhood strata. The survey, which has been conducted annually since 2002, is based on the national Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, and provides representative population-based prevalence estimates. NYC CHS data were weighted to account for unequal selection probabilities and nonresponse, and analyses were age adjusted to the 2000 U.S. Standard Population.

The tobacco-related questions in the NYC CHS assessed in this analysis included current smoking prevalence and CPD. Current smoking was defined as having smoked at least 100 cigarettes in one’s lifetime and currently smoking on all or some days. CPD was defined as the average number of cigarettes smoked per day. Smokers were classified as “heavy daily” if they smoked on all days and smoked 11 or more CPD and “light daily” if they smoked on all days and smoked from 1 to 10 CPD. Nondaily smokers were defined as smoking on some days only.

To account for missing data, CPD was imputed (40 cases in 2002 among 1,455 respondents who smoked daily, 11 cases in 2008 among 727 respondents who smoked daily). Imputation was performed by replacing missing CPD values with the mean values of valid responses. All of the daily smokers were imputed as heavy smokers, as the mean CPD for daily smokers was greater than 10 for each year (14.6 in 2002 and 12.5 in 2008). The analysis was run with and without imputation of CPD, resulting in similar findings for both years. Therefore, imputed values are reported here.

A five-level categorical CPD variable was used to compare the estimated number of cigarettes smoked between 2002 and 2008. The variable categorizes the number of daily smokers in the following CPD categories: 1–5 CPD, 6–10 CPD, 11–15 CPD, 16–20 CPD, and ≥21 CPD. Light smokers (≤10 CPD) were then further classified as “very light” (1–5 CPD) and “medium light” (6–10 CPD) smokers.

We used SAS v.9.1 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) and SAS-callable SUDAAN v.10 (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC) for data analyses, in order to account for the complex design of the NYC CHS. Using the 2002 and 2008 NYC CHS, we compared the prevalence of current smokers, heavy daily smokers, light daily smokers and nondaily smokers among NYC adults. We also conducted a Pearson’s chi-square test to determine any association between survey year and CPD category. Significant changes between 2002 and 2008 were assessed using t tests to compare prevalence estimates of each group; differences were considered significant at α =0.05. The mean CPD among daily smokers and the estimated population of daily smokers in each of the five CPD categories were also compared between 2002 and 2008.

Results

From 2002 to 2008, the adult smoking prevalence declined 27 %, from 21.5 % to 15.8 % (p < 0.001; Table 1). Over the same time period, the prevalence of daily smoking among adults in NYC declined 29 %, (from 14.5 % to 10.3 %; p < 0.001), and the prevalence of heavy daily smoking declined 45 % (from 7.8 % to 4.3 %; p < 0.001). The prevalence of nondaily smoking declined 21 % (from 7.0 % to 5.5 %; p = 0.005). The decline in light daily smoking (from 6.7 % to 6.0 %) was not statistically significant (p = 0.158).

Table 1.

Changes in adult smoking prevalence from 2002 to 2008

| 2002 | 2008 | p value, 2002–2008 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weighted % | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95 % CI | Weighted % | Lower 95 % CI | Upper 95 % CI | ||

| Current smoking | 21.5 | 20.5 | 22.6 | 15.8 | 14.6 | 17.1 | <0.001 |

| Daily smoking | 14.5 | 13.6 | 15.4 | 10.3 | 9.3 | 11.3 | <0.001 |

| Heavy daily smokinga | 7.8 | 7.1 | 8.5 | 4.3 | 3.7 | 4.9 | <0.001 |

| Light daily smoking | 6.7 | 6.1 | 7.4 | 6.0 | 5.2 | 6.8 | 0.158 |

| Nondaily smoking | 7.0 | 6.4 | 7.7 | 5.5 | 4.8 | 6.4 | 0.005 |

Source: New York City Community Health Survey 2002 and 2008. Prevalence estimates are age adjusted to the US 2000 Standard Population. Adults 18 years or older. Bold text indicates significant t test between earliest and latest year available at alpha = 0.05

aCurrent daily smokers who smoke more than 10 cigarettes per day are considered to be heavy daily smokers. Current daily smokers who smoke 10 or fewer cigarettes per day are considered to be light daily smokers. Missing cigarettes per day information was imputed for smokers based on the mean of valid responses. For 2002, 40 cases were imputed among 1,455 respondents who smoked daily. For 2008, 11 cases were imputed among 727 respondents who smoked daily

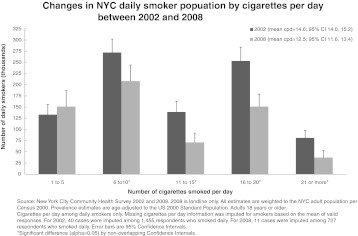

Figure 1 shows the population of daily smokers by five categories of CPD. CPD category is significantly associated with year (X2 = 4.54, p = 0.0012). From 2002 to 2008, there is evidence of declines in all but the very light smokers (1–5 CPD). We estimate that about half as many daily smokers smoked 21 or more CPD in 2008 as compared to smokers in 2002, but there were approximately the same number of very light smokers in both years. The mean CPD among daily smokers declined significantly, from 14.6 to 12.5 (p < 0.001).

FIGURE 1.

Changes in NYC daily smoker population by cigarettes per day between 2002 and 2008.

Conclusions

Our data suggest that, after a 27 % decline in adult smoking prevalence from 2002 to 2008, the remaining smokers show reductions in daily consumption levels and the prevalence of heavy daily smoking. Significant declines were seen among both daily and nondaily smokers between 2002 and 2008. Among daily smokers the largest percent decline was among heavy smokers (45 %), such that by 2008, light smokers comprised the majority of daily smokers. From 2002 to 2008, there were declines among daily smokers in all CPD categories except the very light smokers. Thus, at least as measured through cigarette consumption, these findings are consistent with a shift towards decreased smoking severity, or ‘softening’ among NYC smokers.

Similar to NYC findings, trend analyses of CPD at the state and national level indicate concurrent declines in consumption and smoking prevalence.5,13,14 Our data are also consistent with results from states with comprehensive tobacco control programs.13,15,16 Data from California indicate that, along with a smoking prevalence decline, the prevalence of heavy smoking (25+ CPD) fell by 50 % between 1990 and 1999.5 This is the first study that we know of to show these same trends in a diverse, urban setting.

Evidence also exists in the literature to support the hardening hypothesis; however, the populations and the measures of nicotine dependence in these studies may differ from those in this analysis, which could in part explain the inconsistent findings. The study populations assessed in the Fagerström review, which concluded that countries with low smoking prevalence also had more dependent smokers, included population-based samples at the national level and samples of smokers seeking cessation assistance from 1985 to 1995. However, findings from national samples may not be applicable to all subpopulations in the USA. For example, adults in NYC are more likely to be racial/ethnic minorities, foreign born, and report a lower income than adults nationally, and this may contribute to our unique findings.17 Similarly, Goodwin et al. also showed a hardening effect and used a nationally representative sample as well.6

Further, in the Fagerström review, nicotine dependence was measured through the Fagerström Test of Nicotine Dependence (FTND).4 This is a six-item measure which includes CPD, time to the first cigarette of the day, and difficulty refraining from smoking in places where smoking is banned, among other questions. Similarly, Goodwin measured nicotine dependence using a comprehensive instrument with more than 40 questions.6 In our study, the prevalence of daily and nondaily smoking, as well as CPD, was used to evaluate the hardening hypothesis since more comprehensive measures were not available. There are limitations to this approach as CPD may be influenced by factors such as indoor smoking bans which could serve to reduce daily consumption but not necessarily dependence.13 Hardcore smokers are generally demarcated using a more comprehensive definition, including a combination of quit attempts, nicotine dependence, and duration of smoking.2,9 However, while CPD is not a precise measure of dependence, it has been found to be correlated with other measures of addiction, including difficulty quitting, the key element defining hardcore smokers.18–20 More recently, a retrospective analysis which used a modified FTND score excluding CPD showed that reductions in the number of cigarettes smoked per day was associated with declines in the non-CPD measures of nicotine dependence.10

This study has other limitations as well. The NYC CHS collects self-reported data, which may underestimate the prevalence and frequency of smoking. Cotinine-based smoking prevalence assessed in 2004 was higher than the NYC CHS self-reported prevalence, reflecting a possible underestimation in self-reported smoking measures.21 Finally, in assessing declines in daily smoking prevalence and population changes across CPD categories using cross-sectional data, it is possible that smokers may have shifted across the heavy daily and light daily smoking categories.

Further research is needed to more fully evaluate the hardening hypothesis in NYC. Based on our study, despite an overall smoking prevalence decline of 27 % in NYC since 2002, we saw that cigarette consumption did not increase among the residual smokers, as measured by changes in CPD and prevalence of daily smoking from 2002 to 2008. Tobacco control efforts implemented in NYC, including the current highest combined city/state cigarette excise tax in the country, a comprehensive workplace smoking ban passed in 2002, and hard-hitting media aired since 2006, may have disproportionately affected heavy smokers. These population-based initiatives may counteract the decreased likelihood of successful cessation among the most heavily addicted smokers.5,22 If the smoker population continues to be comprised of increasingly less severe smokers, it will be important for cessation and other tobacco control efforts to be targeted towards this residual group. These findings provide preliminary additional evidence against the hardening hypothesis, and highlight the need for media and cessation efforts aimed at light smokers.

Funding Source

This work was supported by the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. No outside funding was provided.

References

- 1.Frieden TR, Mostashari F, Kerker BD, Miller N, Hajat A, Frankel M. Adult tobacco use levels after intensive tobacco control measures: New York City, 2002–2003. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(6):1016–1023. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.058164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hughes JR. The hardening hypothesis: is the ability to quit decreasing due to increasing nicotine dependence? A review and commentary. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;117(2–3):111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Warner KE, Burns DM. Hardening and the hard-core smoker: concepts, evidence, and implications. Nicotine Tob Res. 2003;5:37–48. doi: 10.1080/1462220021000060428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fagerstrom KO, Kunze M, Schoberberger R, et al. Nicotine dependence versus smoking prevalence: comparisons among countries and categories of smokers. Tob Control. 1996;5:52–56. doi: 10.1136/tc.5.1.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Cancer Institute. Those who continue to smoke. Smoking and Tobacco Control Monograph No. 15. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. NIH Pub. No. 03–5370; 2003.

- 6.Goodwin RD, Keyes KM, Hasin DS. Changes in cigarette use and nicotine dependence in the United States: evidence from the 2001–2002 wave of the national epidemiologic survey of alcoholism and related conditions. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(1):1–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.177311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jarvis MJ, Wardle J, Waller J, Owen L. Prevalence of hardcore smoking in England, and associated attitudes and beliefs: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2003;326:1061. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7398.1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Augustson EM, Marcus SE. Use of the current population survey to characterize subpopulations of continued smokers: a national perspective on the “hardcore” smoker phenomenon. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6(4):621–629. doi: 10.1080/14622200410001727876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Costa ML, Cohen JE, Chaiton MO, Ip D, McDonald P, Ferrence R. “Hardcore” definitions and their application to a population-based sample of smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(8):860–864. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mooney ME, Johnson EO, Breslau N, Bierut LJ, Hatsukami DK. Cigarette smoking reduction and changes in nicotine dependence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13(6):426–430. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shiffman S, Sayette MA. Validation of the nicotine dependence syndrome scale (NDSS): a criterion-group design contrasting chippers and regular smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;79:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. 2008 Community Health Survey. New York, NY: http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/html/survey/survey.shtml. Accessed 9 Aug 2011.

- 13.Gilpin EA, Emery SL, Farkas AJ, Distefan JM, White MM, Pierce JP. The California Tobacco Control Program: a decade of progress, results from the California Tobacco Control Surveys, 1990–1998. La Jolla, CA: University of California, San Diego. http://www.escholarship.org/uc/item/1904q1tf. Accessed 9 Aug 2011.

- 14.O’Connor RJ, Giovino GA, Kozlowski LT, et al. Changes in nicotine intake and cigarette use over time in two nationally representative cross-sectional samples of smokers. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164:750–759. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Delaimy WK, Pierce JP, Messer K, White MW, Trinidad DR, Gilpin EA. The California Tobacco Control Program’s effect on adult smokers: (2) daily cigarette consumption levels. Tob Control. 2007;16:91–95. doi: 10.1136/tc.2006.017061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Biener L, Harris JE, Hamilton W. Impact of the Massachusetts tobacco control programme: population based trend analysis. BMJ. 2000;321:351–354. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7257.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.U.S. Census Bureau (2006–2008). 2006–2008 American Community Survey. http://factfinder.census.gov. Accessed 9 Aug 2011.

- 18.Hymowitz N, Cummings KM, Hyland A, Lynn WR, Pechacek TF, Hartwell TD. Predictors of smoking cessation in a cohort of adult smokers followed for five years. Tob Control. 1997;6(Suppl 2):S57–S62. doi: 10.1136/tc.6.suppl_2.S57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hughes JR, Oliveto AH, Riggs R, et al. Concordance of different measures of nicotine dependence: two pilot studies. Addict Behav. 2004;29:1527–1539. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moolchan ET, Radzius A, Epstein DH, et al. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence and the Diagnostic Interview Schedule. Do they diagnose the same smokers? Addict Behav. 2002;27:101–113. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4603(00)00171-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ellis JA, Gwynn C, Garg RK, et al. Secondhand smoke exposure among nonsmokers nationally and in New York City. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(4):362–370. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB, et al. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. clinical practice guideline. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Service. 2008. http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/tobacco/. Accessed on 9 Aug 2011.