Abstract

Thousands of Americans are killed by gunfire each year, and hundreds of thousands more are injured or threatened with guns in robberies and assaults. The burden of gun violence in urban areas is particularly high. Critics suggest that the results of firearm trace data and gun trafficking investigation studies cannot be used to understand the illegal supply of guns to criminals and, therefore, that regulatory and enforcement efforts designed to disrupt illegal firearms markets are futile in addressing criminal access to firearms. In this paper, we present new data to address three key arguments used by skeptics to undermine research on illegal gun market dynamics. We find that criminals rely upon a diverse set of illegal diversion pathways to acquire guns, gun traffickers usually divert small numbers of guns, newer guns are diverted through close-to-retail diversions from legal firearms commerce, and that a diverse set of gun trafficking indicators are needed to identify and shut down gun trafficking pathways.

Keywords: Gun violence, Gun policy, Gun trafficking, Injury prevention

Gun violence remains a serious problem in the USA, with some 10,226 gun homicide victims1 and 326,090 victims2 of nonfatal violent firearms crimes in 2009. Rates of murder, robbery, and aggravated assault are much higher in large cities than elsewhere.1,2

Much of this serious violence is generated by guns that end up in the wrong hands. Research suggests that only about one of every six firearms used in crime was obtained legally3 and that most serious gun violence is committed by a relatively small number of very active criminals.4–7 Clearly, the USA has a large problem with the illegal acquisition of guns by high-risk individuals who should not have access to them. One broad class of gun-control policy instruments are those designed to influence who has access to different kinds of firearms.8 The intuitive notion here, which is backed by empirical evidence,9,10 is that if we could find a way to keep guns out of the hands of “bad guys” without denying access to the “good guys,” then gun crimes would fall without infringing on the legitimate uses of guns.

In maintaining legal firearms commerce for law-abiding citizens, there is the serious problem of preventing illegal transfers. That task is currently being done very poorly indeed. Loopholes in existing gun laws weaken accountability of licensed gun dealers and private sellers; this facilitates illegal transfers by scofflaw licensed gun dealers, generates difficulty in screening out ineligible buyers, and, most important, results in a vigorous and largely unregulated secondary market—gun sales by private individuals—in which used guns change hands.8 Nonetheless, those who support “supply-side” measures directed at reducing access by those who are legally proscribed suggest that it is feasible to increase the transaction costs in illegal firearm markets and thereby reduce the prevalence of illegal gun possession by criminals.11–14

Much of the evidence in support of supply-side interventions comes from recent analyses of Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (ATF) firearm trace data and firearms trafficking investigations that indicate some percentage of the guns used in crime were recently diverted from legal firearms commerce.4,13–21 Firearm tracing makes it possible, at least in principle, to determine the chain of commerce for a firearm from the point of import or manufacture to the first retail sale (and beyond, in states that maintain records of gun purchases).22 Unfortunately, not all firearms can be traced and firearm trace data have some widely recognized limits.11,23 The National Academies’ Committee to Improve Research Information and Data on Firearms, however, suggests that the validity of conclusions drawn from firearm trace data research depends on the care taken in the application and analyses of these data.23

Among the main findings of these research studies are: (1) New guns are recovered disproportionately in crime;11,13,16–18,22 (2) Some licensed firearm retailers are disproportionately frequent sources of crime guns; these retailers are linked to more guns traced by ATF than would be expected from their overall volume of gun sales;24 (3) Under test conditions, significant proportions of licensed retailers and private party gun sellers will knowingly participate in illegal gun sales;25,26 (4) On average, about one third of guns used in crime in any community are acquired in that community, another third come from elsewhere in the same state, and a third are brought from other states;11,13,16–18,22 (5) There are longstanding interstate trafficking routes for crime guns, typically from states with weaker gun regulations to states with stronger ones. The best known of these is the “Iron Pipeline” from the Southeast to the Middle Atlantic and New England.11,13,16–18,22

Research studies based on analyses of firearm trace data and firearms trafficking investigations have been greeted with a healthy dose of skepticism. Gun rights groups, such as the National Rifle Association,27,28 and certain academics, most notably Professor Gary Kleck of Florida State University,29,30 suggest that firearm trace data cannot be properly used to understand the illegal supply of guns to criminals. These criticisms are then followed by arguments that regulatory and enforcement efforts designed to disrupt illegal firearms markets are futile in addressing criminal access to firearms. In this paper, we present new data to address three key arguments used by skeptics to undermine research on illegal gun market dynamics and associated approaches to limit the illicit acquisition of guns diverted from legal firearms commerce.

The Scale of Gun Trafficking: Big-Time Organized Gun Runners or Diverse Blend of Illegal Diversion Pathways?

One strategy used to refute a proposition is to setup a “straw man” argument. To “attack a straw man” is to create the illusion of having refuted a proposition by substituting a superficially similar proposition (the “straw man”), and refuting it, without ever having actually refuted the original position.31 In a recent UCLA Law Review article, Kleck and Wang set forth the straw man argument that advocates of the proposition that criminals acquire guns through a variety of gun trafficking pathways assert a central role for high-volume gun traffickers, usually involving corrupt or negligent licensed dealers, in supplying guns to criminals.30 Kleck and Wang define a large-scale trafficker as a person who sold 100 guns or more annually and then incorrectly characterize the picture presented by ATF and selected scholars of illegal gun markets as relatively organized markets with significant numbers of high-volume traffickers.30

The academic studies that Kleck and Wang used as reference do not argue, however, that organized high-volume gun traffickers dominate illegal transfers of guns to criminals. Rather, these studies highlight the importance of a flow of new guns to criminal consumers and implicate close-to-retail diversions from licensed dealers as generating a noteworthy minority of recovered crime guns.4,11–13,15,19,20,32 ATF publications make the case that gun trafficking enterprises of many shape and sizes play an important role in supplying crime guns to criminals and do not claim that high-volume, organized gun runners are the modal form of illegal gun diversion in the USA.16–18

In fact, two ATF reviews of gun trafficking investigations explicitly contradict the organized big-time gun trafficking characterization. A 1999 report examining 314 ATF gun show trafficking investigations found that 41 % of these cases involved the diversion of 10 or fewer firearms.33 A 2000 report examining 1,530 gun trafficking investigations made by ATF between July 1, 1996 and December 31, 1998 found that 61 % of the cases involved the diversion of 20 or fewer firearms and concluded that most but not all gun trafficking investigations involve relatively small number of firearms.17

When the existing data are considered, Kleck and Wang’s definition of a large-scale trafficker as someone who has been caught illegally selling 100 or more firearms seems to be set artificially high to support their straw man argument. Guns are durable goods that can remain in the hands of criminals for many years. The illegal diversion of 20, 30, or 50 guns to criminals by one individual in 1 year generates a considerable public safety threat. Clearly, putting this individual out of business and shutting down this more modest pipeline of guns to criminals would increase public safety. It is also important to consider that the number of guns diverted in ATF gun trafficking investigation is based solely on diversions known to the case agent. A gun trafficker caught selling 10 guns to a violent street gang would not be classified as a large-scale gun trafficker under Kleck and Wang’s definition. However, this gun trafficker may have been funneling hundreds of guns to street gangs for many years without being caught by ATF doing so. Kleck and Wang’s use of this definition to make generalizations about the structure of illegal gun markets is highly problematic given the limits of ATF gun trafficking investigation data.

New Data

To shed additional insights on the nature of illegal gun market dynamics, we present new data on 2,608 ATF gun trafficking investigations made between January 1, 1999 and December 31, 2002. These data were collected by ATF as an update to their 2000 Following the Gun report on gun trafficking in the USA. Following the same methodology, a survey instrument was sent to each of ATF’s 23 field divisions requesting information for each gun trafficking investigation made by special agents and the disposition of investigations referred by ATF for prosecution during the study time period. Because these analyses are based on a survey of ATF special agents, they reflect what ATF encountered and investigated in trafficking investigations. As such, they do not necessarily reflect typical criminal diversions of firearms or the typical acquisition of firearms by criminals. A majority of these investigations were still ongoing at the time the survey was distributed; only 40.5 % were fully adjudicated (1,056 of 2,608).

Table 1 presents the gun trafficking pathways identified by ATF agents in the 2,608 investigations. Many gun trafficking investigations involved close-to-retail diversions of guns from legal firearms commerce. A plurality (41.3 %) of investigations involved straw purchasing from federally licensed dealers (Federal Firearms Licensees—FFLs), with firearms trafficked by straw purchasers either themselves or indirectly. The investigations also involved trafficking by unlicensed sellers (27.1 %), by FFLs (6.3 %), illegal diversions at gun shows (7.1 %), and illegal diversions from flea markets and other secondary market sources (4.3 %). When aggregated into one category, firearms stolen from FFLs, residences, and common carriers were involved in 22.5 % of the trafficking investigations.

Table 1.

Gun trafficking pathways identified in ATF investigations

| Source | Number | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Firearms diverted by straw purchaser or straw purchasing ring | 1,078 | 41.3 |

| Firearms diverted by unregulated private sellersa | 708 | 27.1 |

| Prohibited persons lying and buying firearms | 364 | 14.0 |

| Diverting firearms stolen from residence or vehicle | 338 | 13.0 |

| Diverting firearms stolen from FFL | 239 | 9.2 |

| Diverting firearms at gun shows | 185 | 7.1 |

| Firearms diverted by licensed dealer, including pawnbroker | 163 | 6.3 |

| Diverting firearms at flea markets, auctions, or want ads and gun magazines | 112 | 4.3 |

| Diverting firearms stolen from common carrier | 28 | 1.1 |

| Diverting firearms over the Internet | 22 | 0.8 |

| Other | 5 | 0.2 |

N = 2,608

Sum exceeds 100 % since investigations may be included in more than one category. Gun trafficking investigations can be very complex and involve a variety of sources of illegal guns

aAs distinct from straw purchasers and other traffickers

Though 117,138 firearms were involved altogether, most investigations involved relatively small numbers of guns (Table 2).The mean and median were 45.3 and eight guns per case, respectively; a majority involved 10 firearms or less. Large-scale trafficking was uncommon; roughly 5 % of investigations involved more than 100 firearms. One investigation involved 30,000 firearms. Different trafficking pathways were associated with large differences in the numbers of guns linked to the investigations (Table 3). FFLs, including pawnbrokers, have access to a large volume of firearms, so a corrupt licensed dealer can illegally divert large numbers of firearms. FFL traffickers were involved in only 6 % of investigations, but had by far the largest mean number of guns per case (348.7) and accounted for 47 % of all guns linked to the investigations (55,088 of 117,138 firearms). If the investigation involving 30,000 diverted firearms is excluded as an outlier, the mean number of guns per case involving a corrupt FFL drops to only 159.8, this further suggests that large-scale trafficking is a rare event. With or without the investigation involving 30,000 diverted firearms, the median number of guns per FFL trafficker case was 50.

Table 2.

Number of firearms involved in ATF trafficking investigations

| Range | Number of investigations | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| <5 | 962 | 36.9 |

| 5–10 | 516 | 19.8 |

| 11–20 | 427 | 16.4 |

| 21–50 | 374 | 14.3 |

| 51–100 | 165 | 6.3 |

| 101–250 | 89 | 3.4 |

| 251 or greater | 54 | 2.1 |

| Unknown | 21 | 0.8 |

N = 2,608

Table 3.

Volume of firearms diverted, by trafficking pathway

| Source | N (%) | N firearms | Mean | Median |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Firearms diverted by straw purchaser or straw purchasing ring | 1,074 (41.5) | 38,032 | 35.4 | 12 |

| Firearms diverted by unregulated private sellersa | 697 (26.9) | 38,734 | 55.6 | 7 |

| Prohibited persons lying and buying firearms | 364 (14.1) | 8,192 | 22.5 | 3 |

| Diverting firearms stolen from residence or vehicle | 337 (13.0) | 7,758 | 23.0 | 5 |

| Diverting firearms stolen from FFL | 238 (9.2) | 6,694 | 28.1 | 16 |

| Diverting firearms at gun shows | 182 (7.0) | 30,471 | 167.4 | 72 |

| Firearms diverted by licensed dealer, including pawnbroker | 158 (6.1) | 55,088 | 348.7 | 50 |

| Diverting firearms at flea markets, auctions, or want ads and gun magazines | 110 (4.3) | 23,164 | 210.6 | 69 |

| Diverting firearms stolen from common carrier | 28 (1.1) | 994 | 35.5 | 14 |

| Diverting firearms over the Internet | 21 (0.8) | 6,335 | 301.7 | 50 |

N investigations = 2,587

N firearms included = 117,138

Sum exceeds 100 % since the investigations may be included in more than one category. Table excludes 22 cases with an unknown number of diverted firearms

aAs distinct from straw purchasers and other traffickers

New Crime Guns: An Indicator of Illegal Gun Diversion or Theft?

ATF and academic analyses of firearms trace data typically focus on a critical dimension of the illegal firearms market: the time between a firearm’s first sale at retail and its subsequent recovery by a law enforcement agency, most often in connection with a crime (“time-to-crime”). Law enforcement investigators consider a traced firearm with short time-to-crime as possibly having been recently and illegally diverted from a retail outlet.18 For investigative and tactical purposes, guns with quick time-to-crime offer law enforcement an opportunity to identify illegal gun transfers soon after they occur. Newer guns have also passed through fewer hands, making it much easier for law enforcement to investigate illegal gun trafficking and to mount prosecutions. Records are likely to be more complete and more available; individuals listed on paperwork are easier to find; guns are less likely to have been resold, given away, or stolen; and the chain of transfers to illicit consumers is likely to be shorter.4

Franklin Zimring first documented the disproportionate representation of new guns among those recovered by the police.20 More recently, Kennedy, Piehl, and Braga analyzed comprehensive trace data for firearms recovered from Boston youth ages 21 and under between 1991 and 1995.4 They documented that 26 % of traced firearms were recovered in crime within 2 years of their first retail sale and none of these new guns were recovered in the possession of the first retail buyer.4 Cook and Braga analyzed comprehensive trace data on handguns recovered in 32 US cities participating in ATF’s YCGII program in 1999.11 They found that 32 % of traced handguns were recovered within 3 years of their first retail purchase and only 18 % of these new guns were recovered in the possession of the first retail buyer. A California study of crime guns recovered from adolescents and young adults in 1999 emphasized the link between time to crime and policies regulating the purchase of firearms.22 A time-to-crime of less than 3 years was observed for 17.3 % of guns recovered from persons younger than 18 years, who cannot purchase guns themselves, but 34.6 % of guns recovered from persons ages 21–24.

While survey research highlights the importance of theft and secondary market acquisitions in supplying adult criminals and juveniles with guns,34–36 these studies also suggest a fairly substantial role, either direct or indirect, for retail outlet sales in supplying criminals with guns. About 27 % of state prisoners in a US Bureau of Justice Statistics survey said they acquired their most recent handgun from a retail outlet.36 Similarly, Wright and Rossi reported that 21 % of male prisoners had acquired their most recent handgun from a licensed dealer.35 Sheley and Wright found that 32 % of juvenile inmates had asked someone, typically a friend or family member, to purchase a gun for them in a gun shop, pawnshop, or other retail outlet.34 This purchasing arrangement, known as a “straw purchase,” is likely to result in relatively short times-to-crime. All three survey studies also find that “street” and “black market” sources are important sources that may well include traffickers who are buying from retail outlets and selling on the street.4,21 Regrettably, since surveys of criminals only ask about proximate sources of illegal firearms, these research studies are limited in establishing the role of gun trafficking in criminal acquisition of firearms as they do not ascertain how guns are diverted into these “street” and “black market” sources.4,21

Critics suggest that a short average time-to-crime among traced crime guns in a given area may serve more as an indirect indicator of property crime, especially burglary, in that area rather than of widespread firearms trafficking. Kleck and Wang, for instance, argue that many guns move quickly into criminal hands because they were stolen from their owners shortly after retail purchase.30 Their basic thesis is that new crime guns are usually stolen because (1) criminals prefer new guns to older guns and (2) criminals who steal guns disproportionately retain newer guns for later personal use.

Unfortunately, there is little survey research evidence to support their overall thesis. Neither the Wright and Rossi survey of convicted felons35 nor the Sheley and Wright survey of juvenile inmates and high school students34 asked whether respondents preferred new guns. In those studies, convicted felons and juveniles report as some of the “very important” characteristics of desirable handguns that they be accurate, untraceable, well made, easy to shoot, concealable, easy to get (both the gun and ammunition), and have sufficient firepower.34,35 Stolen guns that had these traits were more likely to be kept by criminals who stole them. These desirable traits are not linked to the age distinctions (such as a time-to-crime of 3 years or less) that most academic analyses of firearm trace make in characterizing a crime gun as new or old.4,11,13,14

There is some evidence that certain criminal consumers do have preferences for newer guns. In Boston, interviews with youthful probationers in the mid-1990s revealed that they preferred modern and stylish semiautomatic pistols that were “new in the box.”4 The preference for newer semiautomatic pistols that were still in the original packaging by the manufacturer arose from “street wisdom” that older, less expensive firearms may have a “body” on it, and they wished to avoid being caught and charged with crimes they did not personally commit.4 Similarly, in Maryland, Webster et al. found that older teens had a strong preference for guns which were new due to their concerns about being linked through ballistics imaging to crimes that may have been committed with secondhand guns.37 New pistols that are still in the original packaging are usually acquired through FFLs or directly from manufacturers rather than stolen from their owners’ residences. To the extent that gun age may matter, desire for new guns in the manufacturers’ original packaging would support the perspective that close-to-retail diversions are an important source of guns for certain young criminals.

Theft risk varies by source and type of firearm. Residential theft is the most frequent source of stolen guns for gun thieves, with between 500,000 and 600,000 guns stolen from residences each year.32,38 This yearly estimate dwarfs the number of stolen guns reported in ATF investigations involving thefts from FFLs (6,694 guns) and common carriers (994 guns) over a 4-year period (Table 3). To understand the age distribution of stolen guns, therefore, it is important to examine the age distribution of privately held guns in gun-owning households.

The most detailed national survey on the private citizen gun stock is the National Survey of the Private Ownership of Firearms (NSPOF) conducted in 1994.38 According to the NSPOF, the average firearm was acquired 13 years earlier and 22.4 % were acquired within the past 2 years.38 Only 64 % of firearms acquired within the past 2 years were reported as new when the respondent first acquired it. This suggests that, if recovered in crime, 14.3 % of firearms in private hands (0.224 × 0.64 × 100) would be traced by ATF and characterized as having a time-to-crime of 2 years or less. In contrast, analyses of ATF trace data for crime guns recovered in 32 US cities participating in the YCGII program in 1999 found that the median time-to-crime for all recovered crime guns was 5.7 years, and 25.9 % of crime guns had a time-to-crime of 2 years or less.39 If property crime, especially burglary, were the predominant generator of traced crime guns with short time-to-crime, the age distribution of the private gun stock would more closely match the age distribution of recovered crime guns.

Finally, there is a growing body of evaluation evidence that challenges Kleck and Wang’s assertion that most short time-to-crime guns are obtained through theft by demonstrating a clear link between interventions focused on retail sales practices and subsequent reductions in new guns recovered in crime. In Detroit and Chicago, the number of guns recovered within a year of first retail sale from someone other than the original purchaser was sharply reduced after undercover police stings and lawsuits targeted scofflaw retail dealers.40 In Boston, a gun market disruption strategy focused on the illegal diversion of new handguns from retail outlets in Massachusetts, southern states along Interstate 95, and elsewhere resulted in a significant reduction in the percentage of handguns recovered in crime by the Boston Police Department that were new.14 In Milwaukee, the number of guns recovered within a year of first retail sale from someone other than the original purchaser dramatically decreased after voluntary changes in the sales practices of a gun dealer that received negative publicity for leading the USA in selling the most guns recovered by police in crime.41

New Data

Another way to examine the role of theft in supplying guns to criminals is to compare the age distribution of crime guns and the age distribution of legally owned firearms in the USA over a similar time period. If theft is the predominant source of crime guns, the age distribution of crime guns should follow the age distribution of legally owned firearms—the broader pool of guns at risk for theft. Thieves stealing firearms would not know the age of the firearms they were stealing; the selection of guns would resemble a random selection process with respect to the age of the stolen guns. Conversely, if close-to-retail illegal diversions of guns from licensed dealers contribute to the supply of guns to criminals, then the age distribution of crime guns should be disproportionately concentrated among newer guns relative to the age distribution of all legally owned firearms. The following new data are used to examine this proposition.

We compare the age distribution of 85,511 crime guns recovered by US law enforcement agencies and traced by ATF in 1999 to the production history of all firearms manufactured or imported for sale in the USA between 1979 and 1998. We selected 1999 because this was the first year that ATF traced all firearms to their first retail sale regardless of the length of time between the first retail sale and subsequent recovery in crime. ATF also maintains data on the number of firearms produced by US manufacturers, the number of firearms exported by US manufacturers, and the number of firearms imported by foreign manufacturers for a given calendar year.42 (The data were collected through a National Institute of Justice grant to study illegal gun markets that was completed prior to the 2003 passage of the Tiahrt Amendment that greatly restricts the use of such data by non-law enforcement personnel.43)

Table 4 presents annual aggregate handgun data for 1979–1998. Firearm manufacturers produced an average of 2,264,000 handguns for sale each year and 45,275,000 handguns in total. Only 3.8 % of these handguns were produced for sale in 1998. However, 17.3 % of recovered crime guns in 1999 were first sold at retail in 1998. One-year-old handguns are overrepresented by a factor of nearly 4.6 times when the handgun production history age distribution and time-to-crime distribution are compared.

Table 4.

The age distribution of handguns produced for the US market, 1979–1998, and the time-to-crime age distribution of traced handguns recovered in crime

| Year | Annual N handguns produced for US market | % Distribution of handguns produced | % Distribution of traced 1999 crime handguns first retail sale |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1979 | 2,171 | 4.80 | 1.54 |

| 1980 | 2,449 | 5.41 | 1.88 |

| 1981 | 2,591 | 5.72 | 1.92 |

| 1982 | 2,708 | 5.98 | 1.84 |

| 1983 | 2,219 | 4.90 | 1.80 |

| 1984 | 1,905 | 4.21 | 1.94 |

| 1985 | 1,684 | 3.72 | 1.97 |

| 1986 | 1,538 | 3.40 | 2.23 |

| 1987 | 1,842 | 4.07 | 2.60 |

| 1988 | 2,236 | 4.94 | 2.97 |

| 1989 | 2,353 | 5.20 | 3.60 |

| 1990 | 2,110 | 4.66 | 4.27 |

| 1991 | 1,941 | 4.29 | 5.29 |

| 1992 | 2,803 | 6.19 | 7.63 |

| 1993 | 3,881 | 8.57 | 9.01 |

| 1994 | 3,324 | 7.34 | 6.86 |

| 1995 | 2,199 | 4.86 | 7.30 |

| 1996 | 1,821 | 4.02 | 8.36 |

| 1997 | 1,773 | 3.92 | 9.70 |

| 1998 | 1,727 | 3.81 | 17.30 |

The annual number of handguns produced for US markets equals the total of the number of handguns produced by US manufacturers, minus the number of firearms exported by US manufacturers to foreign countries, plus the number of handguns imported to the US by foreign manufacturers for a given calendar year. While guns are durable goods, a small number of firearms are removed each year from the private stock of guns due to various forms of depreciation such as confiscation by law enforcement agencies and disposal by owners. Research suggests that some 200,000 guns are confiscated by law enforcement agencies each year and some 36,000 guns are thrown away by their owners each year.12,34 We ran the same analyses presented here with various adjustments for depreciation; there were no substantive differences in the results of these analyses. These analyses are available upon request from the authors

Numbers are reported in thousands

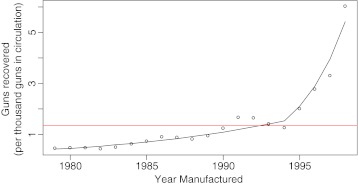

We fit a binomial regression model to the annual aggregate crime gun recovery data to assess the relationship between the year the gun was manufactured and the probability of it being recovered in crime. As Figure 1 shows, there is a sharp increase in the rate of recovery for guns manufactured after 1994. To allow the model to capture this, we allowed the coefficient on year to change in 1994. The model has the form:

|

1 |

FIGURE 1.

Guns recovered as a fraction of guns in circulation by year manufactured. Points computed from the raw data. The horizontal line is what we would expect if the recovered guns were a random sample from the guns in circulation. The curve is the fit from the binomial regression model.

For years prior to 1994, the value of exp(β1) − 1 gives the percent increase in the probability of a gun’s recovery in crime relative to the prior year. After 1994, exp(β1 + β2) − 1 gives the percent increase in the probability of a gun’s recovery in crime relative to the prior year. Note that this is essentially a logistic regression model; however, we model the log probability rather than the log odds. Since the recovery probabilities are small, the log and the logit are nearly identical. However, relative rates, which the model in (1) estimates, are generally easier to understand than relative odds. Under the hypothesis that the age of the gun is unrelated to its probability of being recovered, we would expect β1 and β2 to be 0.

Table 5 shows the parameter estimates. For guns manufactured prior to 1994, the newer guns are more likely to be recovered in crime with each additional year increasing the probability of recovery by 9 %. The recovery rate accelerates after 1994; with each additional year, the recovery rate increases by 37 %. The curve plotted in Figure 1 shows the model fits closely to the data. This analysis provides strong evidence that the newer guns are disproportionately recovered in crime relative to their prevalence among guns in circulation.

Table 5.

Estimates of the average year-to-year percent increase in recovery rates

| Model parameter | Estimate (%) | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before 1994 | exp(β1) − 1 | 9.3 | 9.0%, 9.5% |

| After 1994 | exp(β1 + β2) − 1 | 37.1 | 36.3%, 37.9% |

Years of data = 20

Null deviance = 34,542.8, with df = 19

Model deviance = 1,345.9, with df = 17

The age distributions of many specific types of crime guns are disproportionately concentrated among newer guns. Table 6 presents overrepresentation ratios for the basic firearm types (handguns, rifles, and shotguns) and for selected manufacturers featured in ATF trace reports as the makers of frequently recovered crime guns.16,18 Overall, firearms produced in 1998 were overrepresented by a factor of 3.7 times among recovered crime guns that were traced in 1999. Overrepresentation was greater for handguns (ratio of 4.6) than for rifles (2.2) or shotguns (2.8). Selected semiautomatic pistols generally had higher overrepresentation ratios than did revolvers. The highest overrepresentation ratio for guns included in the analysis (6.0) was seen for Bryco Arms pistols.

Table 6.

Overrepresentation ratios for selected firearm types and manufacturers

| Firearm | % Distribution produced in 1998 | % Distribution 1999 crime guns first sold in 1998 | Overrepresentation ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Firearms, all manufacturers | 4.4 | 16.3 | 3.7 |

| Handguns, all manufacturers | 3.8 | 17.3 | 4.6 |

| Rifles, all manufacturers | 5.3 | 11.8 | 2.2 |

| Shotguns, all manufacturers | 4.5 | 12.7 | 2.8 |

| Selected revolvers | |||

| Colt revolvers | 5.6 | 10.5 | 1.9 |

| Smith & Wesson revolvers | 1.9 | 6.4 | 3.4 |

| Sturm Ruger revolvers | 6.5 | 11.7 | 1.8 |

| Selected semiautomatic pistols | |||

| Bryco pistols | 5.7 | 34.0 | 6.0 |

| Lorcin pistols | 7.1 | 25.3 | 3.6 |

| Smith & Wesson pistols | 4.7 | 19.9 | 4.2 |

| Sturm Ruger pistols | 6.7 | 23.6 | 3.5 |

All figures are rounded to the first decimal place. Over-representation ratios were calculated by dividing the percentage of a particular gun produced for sale in 1998 into the percentage of 1999 traced crime guns of that type that were first sold at retail in 1998

Should Obliterated Serial Numbers Be the Only Indicator of Gun Trafficking?

ATF and gun trafficking researchers suggest that an obliterated serial number on a recovered crime gun is a very strong indicator of illegal gun trafficking.4,11,14,18,39 Since defacing the serial numbers on a firearm is itself a crime, obliterated serial numbers establish that a criminal possessed the gun at some time and also constitute strong evidence that some past possessor wanted to obstruct tracing and prevent the firearm from being linked to a past transfer. Despite the obvious advantage in avoiding detection by law enforcement agencies, most gun traffickers do not obliterate the serial numbers on their guns. In the 2,608 ATF gun trafficking investigations described earlier, agents reported violations of Federal Law 18 USC § 922(k) barring possession of and commerce in firearms with obliterated serial numbers in only 7.8 % (N = 203) of cases. This proportion varied little by the specific trafficking channel involved, except for cases involving trafficking over the Internet (18.2 %; Table 7).

Table 7.

Firearms diversion channels identified in ATF investigations by reported violations of Federal Law 18 USC § 922(k) barring possession and commerce of firearms with obliterated serial numbers

| Source | 922(k) violation N reported | % of Channel N |

|---|---|---|

| Firearms diverted by straw purchaser or straw purchasing ring | 45 | 4.2% of 1,078 |

| Firearms diverted by unregulated private sellersa | 66 | 9.3% of 708 |

| Prohibited persons lying and buying firearms | 15 | 4.1% of 364 |

| Diverting firearms stolen from residence or vehicle | 10 | 2.9% of 338 |

| Diverting firearms stolen from FFL | 17 | 7.1% of 239 |

| Diverting firearms at gun shows | 12 | 6.5% of 185 |

| Firearms diverted by licensed dealer, including pawnbroker | 10 | 6.1% of 163 |

| Diverting firearms at flea markets, auctions, or want ads and gun magazines | 7 | 6.3% of 112 |

| Diverting firearms stolen from common carrier | 2 | 7.1% of 28 |

| Diverting firearms over the Internet | 4 | 18.2% of 22 |

Sum exceeds 100 % since the investigations may be included in more than one category

aAs distinct from straw purchasers and other traffickers

The small proportion of obliterated serial numbers may reflect the presence of lax gun laws and weak penalties for making illegal gun sales as well as low risks of detection, arrest, and prosecution for gun trafficking across many jurisdictions in the USA. In these low-risk environments, the obliteration of serial numbers to conceal illegal purchases of firearms may not be necessary. As such, it may not be surprising to find low overall rates of serial number obliteration violations in these ATF gun trafficking investigations.

Data on obliterated serial numbers are very limited and must be used with great caution to avoid incorrect conclusions about illegal gun market dynamics. In particular, while obliterated serial numbers are an important indicator of illegal gun trafficking, they are insufficient in themselves; other indicators must also be used to determine whether gun trafficking has occurred. Kleck and Wang, in contrast, use obliterated serial number data as their sole measure to develop a tentative estimate of the trafficking share of crime guns.30 Based on their own interpretation of published ATF data on crime guns recovered from 46 US cities in 2000,18 they posit that only 1.6 % of handguns with time-to-crime of 1 year or less had obliterated serial numbers. It is important to note that the column of a key ATF table contained information on only 52 handguns.18 Without any supporting evidence or analytic rationale, Kleck and Wang then argued that some guns with obliterated serial numbers were probably not trafficked and estimated that the trafficked share of crime guns is probably less than 1 %.

Kleck and Wang misinterpreted a key ATF table that explored possible links between guns with obliterated serial numbers and multiple handgun sales.18 To be included in that table, an obliterated serial number gun had to be traced, which requires the serial number to be restored. Many handguns with obliterated serial number cannot be traced, and the guns in the table therefore represent a selective undercount of guns with obliterated serial numbers. Kleck and Wang’s estimate is therefore incorrect.

ATF does not report the success rate of serial number restoration attempts; therefore, it is very difficult to make a grounded calculation of the true prevalence of handguns with obliterated serial numbers and a time-to-crime of 1 year. However, since 2,705 handguns with obliterated serial numbers were included in the obliterated serial number section of the ATF report,18 the 52 handguns with restored serial numbers that form the basis of Kleck and Wang’s estimate are almost certainly a sizeable underestimate of the true prevalence of recovered handguns with obliterated serial numbers and short times to crime.

Kleck and Wang also use obliterated serial number data in two exploratory multivariate analyses.30 The first uses principal components techniques to understand the relationship among various potential gun trafficking indicators, such as median time-to-crime, gun sold by first retail dealer located over 250 miles away, and the percent of recovered guns with obliterated serial numbers. They find that many of their indicators load on factors separate from the factor that mainly reflects the prevalence of guns with obliterated serial numbers; since they regard obliterated serial number guns as a strong trafficking indicator, they conclude that the other indicators must be measuring something other than gun trafficking and are probably not good trafficking indicators.30 The second analysis uses multiple regression models to examine the causal effects of the percent of recovered guns with obliterated serial numbers on criminal gun possession (measured as the percent of homicides committed with guns), murder rates, robbery rates, and assault rates. They find that the prevalence of obliterated serial number guns is not significantly related to criminal gun possession or violent crime rates.

Unfortunately, the ATF report from which Kleck and Wang collected their obliterated serial number data clearly states that these data were seriously limited: they were reported from just eight cities, did not include long guns, and did not include older guns.18 The flaws in the data raise serious doubts about the reliability and validity of Kleck and Wang’s conclusions.

Conclusion

It is important to note that the empirical data used in this article to refute wrong-headed claims by Kleck and Wang on illegal gun market dynamics have some noteworthy limitations. As described earlier, ATF firearms trace data may not be representative of firearms possessed and used by criminals; furthermore, a substantial proportion of recovered firearms cannot be traced to the first known retail sale.7 ATF gun trafficking investigation data only provide information on gun trafficking investigations that come to the attention of ATF agents.12 These gun trafficking enterprises may not be representative of broader gun trafficking pathways at work in the USA. The trace- and investigation-based information that results is biased to an unknown degree by these factors. These concerns certainly apply to the trace and investigation data used in the empirical analyses presented here. However, as suggested by the National Research Council’s Committee to Improve Research Information and Data on Firearms, these data can provide policy relevant insights on illegal gun market dynamics when conclusions are based on careful analyses that are coupled with clear acknowledgments of the data limitations.23

The research presented here identifies three important points about how criminals acquire guns. First, they rely on a diverse set of illegal pathways, including corrupt licensed dealers, unlicensed sellers, straw purchasers, residential theft, and theft from licensed dealers, common carriers, and firearm manufacturers. Organized, large-scale trafficking exists, but it is not predominant. Where they occur, high-volume gun trafficking operations are attractive targets for regulatory and enforcement efforts. (Certain trafficking routes, such as those supplying firearms to large criminal organizations in Mexico, may behave differently.) Second, new guns are disproportionately recovered in crime, suggesting an important role for close-to-retail diversion of guns in arming criminals. Third, given the diversity of channels through which criminals can acquire guns, law enforcement agencies need to consider a variety of gun trafficking indicators that go well beyond whether a crime gun is recovered with an obliterated serial number or not.

Our findings refute three key arguments against the proposition that interventions aimed at curtailing illegal transfers of firearms could be used to good effect in reducing gun availability to criminals and gun crime. The case for a supply-side approach to gun violence is well supported by the empirical evidence on illegal gun market dynamics. To date, however, there is little empirical evidence that such an approach reduces rates of gun crime. We believe that it is time to develop experimental evidence on whether interventions designed to limit illegal transfers of firearms can reduce gun violence.

References

- 1.US Federal Bureau of Investigation. Crime in the United States, 2009. Available at http://www2.fbi.gov/ucr/cius2009. Accessed March 18, 2011.

- 2.Truman JL, Rand MR. Criminal victimization, 2009. Washington: Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reiss AJ, Roth J. Understanding and preventing violence. Washington: National Academy Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kennedy DM, Piehl AM, Braga AA. Youth violence in Boston: gun markets, serious youth offenders, and a use-reduction strategy. Law & Contemp Probl. 1996;59:147–196. doi: 10.2307/1192213. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braga AA. Serious youth gun offenders and the epidemic of youth violence in Boston. J Quant Criminology. 2003;19:33–54. doi: 10.1023/A:1022566628159. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braga AA, Hureau DM, Winship C. Losing faith? Police, black churches, and the resurgence of youth violence in Boston. Ohio St J Crim Law. 2008;6:141–172. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cook PJ, Ludwig J, Braga AA. The criminal records of homicide offenders. JAMA. 2005;294:598–601. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.5.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cook PJ, Braga AA, Moore MH. Gun control. In: Wilson JQ, Petersilia J, editors. Crime and public policy. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2011. pp. 257–292. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wintemute GJ, Wright MA, Drake CM, Beaumont JJ. Subsequent criminal activity among violent misdemeanants who seek to purchase handguns: risk factors and effectiveness of denying handgun purchase. JAMA. 2001;285:1019–1026. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.8.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wright MA, Wintemute GJ, Rivara F. Effectiveness of a program to deny legal handgun purchase to persons believed to be at high risk for firearm violence. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:88–90. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.89.1.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cook PJ, Braga AA. Comprehensive firearms tracing: strategic and investigative uses of new data on firearms markets. Arizona Law Rev. 2001;43:277–309. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braga AA, Cook PJ, Kennedy DM, Moore MH. The illegal supply of firearms. In: Tonry M, editor. Crime and justice: a review of research. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2002. pp. 229–262. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pierce GL, Braga AA, Hyatt RR, Koper CS. The characteristics and dynamics of illegal firearms markets: implications for a supply-side enforcement strategy. Justice Q. 2004;21:391–422. doi: 10.1080/07418820400095851. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Braga AA, Pierce GL. Disrupting illegal firearms markets in Boston: the effects of operation ceasefire on the supply of new handguns to criminals. Criminol Publ Pol. 2005;4:717–748. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9133.2005.00353.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koper CS. Purchase of multiple firearms as a risk factor for criminal gun use. Criminol Publ Pol. 2005;4:749–778. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9133.2005.00354.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crime gun trace analysis reports (1997): the illegal firearms market in 17 communities. Washington: Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Following the gun: enforcing federal laws against firearms traffickers. Washington: Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crime gun trace analysis (2000): national report. Washington: Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moore MH. Keeping handguns from criminal offenders. Annals. 1981;452:22–32. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zimring FE. Street crime and new guns: some implications for firearms control. J Crim Justice. 1976;4:95–107. doi: 10.1016/0047-2352(76)90059-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wachtel J. Sources of crime guns in Los Angeles, California. Policing. 1998;21:220–239. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wintemute GJ, Romero MP, Wright MA, Grassel KM. The life cycle of crime guns: a description based on guns recovered from young people in California. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43:733–742. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2003.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wellford C, Pepper JV, Petrie CV, editors. Firearms and violence: a critical review. Washington: The National Academies Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wintemute GJ. Risk factors among handgun retailers for frequent and disproportionate sales of guns used in violent and firearm related crimes. Inj Prev. 2005;11:357–363. doi: 10.1136/ip.2005.009969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sorenson SB, Vittes KA. Buying a handgun for someone else: firearm retailer willingness to sell. Inj Prev. 2003;9:147–150. doi: 10.1136/ip.9.2.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wintemute GJ. Firearm retailers’ willingness to participate in an illegal gun purchase. J Urban Health. 2010;87:865–878. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9489-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Rifle Association. Firearm traces: The anti-gunners’ big lie. Available at: http://www.nraila.org/Issues/Articles/Read.aspx?id=12&issue=014. Accessed January 2, 2010.

- 28.Blackman PH. Proceedings of the Homicide Research Working Group meetings, 1997 and 1998. Washington: National Institute of Justice, US Department of Justice; 1999. The limitations of BATF firearms tracing data for policymaking and homicide research; pp. 58–113. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kleck G. BATF gun trace data and the role of organized gun trafficking in supplying guns to criminals. St Louis Univ Publ Law Rev. 1999;18:23–45. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kleck G, Wang S-YK. The myth of big-time gun trafficking and the overinterpretation of gun tracing data. UCLA Law Rev. 2009;56:1233–1294. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pirie M. How to win every argument: the use and abuse of logic. UK: Continuum International Publishing Group; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cook PJ, Molloconi S, Cole T. Regulating gun markets. J Crim Law Criminol. 1995;86:59–92. doi: 10.2307/1144000. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gun shows: Brady checks and crime gun traces. Washington: US Department of the Treasury and US Department of Justice; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sheley JF, Wright JD. In the line of fire: youth, guns, and violence in urban America. New York: Aldine de Gruyter; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wright JD, Rossi PH. Armed and considered dangerous. 2. New York: Aldine de Gruyter; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Survey of state prison inmates, 1991. Washington: Bureau of Justice Statistics, US Department of Justice; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Webster DW, Freed LH, Frattaroli S, Wilson MH. How delinquent youth acquire guns: initial versus most recent gun acquisitions. J Urban Health. 2002;79:60–69. doi: 10.1093/jurban/79.1.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cook PJ, Ludwig J. Guns in America: results of a comprehensive national survey on firearms ownership and use. Washington: Police Foundation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Crime gun trace analysis (1999): national report. Washington: Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Webster DW, Zeoli AM, Bulzacchelli MT, Vernick JS. Effects of police stings of gun dealers on the supply of new guns to criminals. Inj Prev. 2006;12:225–230. doi: 10.1136/ip.2006.012120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Webster DW, Vernick JS, Bulzacchelli MT. Effects of a gun dealer’s change in sales practices on the supply of guns to criminals. J Urban Health. 2006;83:778–787. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9073-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Commerce in firearms in the United States. Washington: US Department of the Treasury; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pierce GL, Braga AA, Koper CS, et al. The characteristics and dynamics of gun markets: report submitted to the US National Institute of Justice. Boston: Northeastern University; 2003. [Google Scholar]