Abstract

Background

Residual Perthes and Perthes-like hip deformities are complex and may encompass proximal femoral deformity, secondary acetabular dysplasia, and associated intraarticular abnormalities. These intraarticular abnormalities have not been well characterized but may influence surgical technique and treatment outcomes.

Questions/purposes

We (1) determined the characteristics of intraarticular disease associated with residual Perthes-like hip deformities; and (2) correlated these intraarticular abnormalities with clinical characteristics and radiographic parameters of hip morphology.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed 35 patients (36 hips) with residual Perthes or Perthes-like deformities and hip symptoms treated using a surgical dislocation. There were 24 males and 11 females; mean age was 18.5 years (range, 10–36 years). We prospectively documented all intraoperative findings and comprehensively reviewed all radiographs.

Results

Labral abnormalities and acetabular and femoral head cartilage abnormalities were present in 76%, 59%, and 81% of hips, respectively. Male sex was associated with severe chondromalacia (64% versus 27%), femoral head chondromalacia (92% versus 55%), and advanced radiographic osteoarthritis (44% versus 9%). Stulberg classification of 3 or greater was associated with moderate to severe acetabular chondromalacia (71% versus 30%). Lateral center-edge angle > 20° and acetabular inclination < 15° correlated with severe chondromalacia (73% versus 38%; 23% versus 70%). Center-trochanteric distance < −1.7 was associated with labral tears (90% versus 57%).

Conclusions

Chondral lesions and labral tears are common in symptomatic patients with residual Perthes or Perthes-like deformities. Male sex, a high trochanter, and joint incongruity are associated with more advanced intraarticular disease. Secondary acetabular dysplasia seems to protect the articular cartilage in that hips with acetabular dysplasia had less chondromalacia.

Introduction

Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease in childhood, both treated and untreated, can lead to residual hip deformity that may become symptomatic in adolescence or early adulthood and progress to secondary osteoarthritis [2, 15, 20, 23]. A Perthes-like deformity of the hip can also result from various childhood hip disorders (infection, trauma, avascular necrosis secondary to hip dysplasia treatment) resulting in a large aspheric femoral head, a short femoral neck, and/or trochanteric overgrowth [4, 10, 11, 17, 31]. Surgical treatment of these deformities can be complex and is variable depending on the specifics of each case. The general goals of surgery are to relieve femoroacetabular impingement (FAI), maintain or achieve hip stability, and correct associated intraarticular lesions (labrum, articular cartilage, ligamentum teres) [4, 11, 25]. Treatment options may include proximal femoral osteotomy [5], femoral osteochondroplasty, relative femoral neck lengthening [27], trochanteric advancement [13, 19], periacetabular osteotomy [4, 11], and management of associated intraarticular abnormalities (labral, articular cartilage, and osteochondral lesions) [25].

Surgical hip dislocation provides the surgeon with optimal visualization of the proximal femur and acetabulum [14]. Intraoperative ROM testing, while visualizing the relationship between the proximal femur and acetabulum, also allows the surgeon to directly observe any pathologic interactions during dynamic testing. Furthermore, the integrity of the acetabular labrum and chondral surfaces of the acetabulum and femoral head are directly observed. The intraarticular disease patterns in Perthes-like hips, however, are not well described in the literature. Such information is important for surgeons to anticipate the technical aspects of the procedure and to develop a comprehensive preoperative plan. Additionally, factors associated with intraarticular abnormalities and articular cartilage disease may impact patient selection for surgery and are likely to have prognostic importance.

The purposes of this study were to: (1) determine the characteristics of intraarticular disease (labral, articular cartilage, osteochondral, and ligamentum teres lesions) associated with residual Perthes-like hip deformities; and (2) investigate the association of these intraarticular abnormalities with clinical characteristics and radiographic parameters of hip morphology.

Patients and Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the radiographs and operative data sets of all 35 patients (36 hips) treated using a surgical dislocation for Perthes-like deformities from January 2008 to February 2011. During this time period, a total of 159 surgical dislocations in 145 patients were performed. The senior author’s database was searched for patients with the diagnosis of Perthes or Perthes-like conditions. All patients had persistent hip pain that was refractory to at least 3 months of nonoperative treatment consisting of activity modification, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medications, and physical therapy. We included patients with prior initial treatment (casting, proximal femoral osteotomies, and various pelvic osteotomies). The lead author reviewed all patient records and radiographs, finding 26 of the hips had true Perthes disease, whereas 10 other patients had a Perthes-like deformity as a result of other pediatric disease processes. Of these Perthes-like hips, four were a result of dysplasia, three secondary to hip sepsis/osteomyelitis, one femoral avascular necrosis, one postoperative slipped capital femoral epiphysis, and one proximal focal femoral deficiency. Perthes-like hip deformities encompass specific features including an aspheric femoral head, short femoral neck, high greater trochanter, and variable secondary acetabular dysplasia (Fig. 1). The 36 surgical hip dislocation procedures were performed for management of FAI and associated intraarticular hip disease (labral, articular cartilage, and ligamentum teres abnormalities). Twenty-five hips were in male patients and 11 in females. The average patient age at the time of surgery was 18.5 years (range, 10–36 years). The average body mass index was 26.5 kg/m2 (range, 18.4–41.9 kg/m2). There were equal numbers of left- and right-sided hips (N = 18 [50%]).

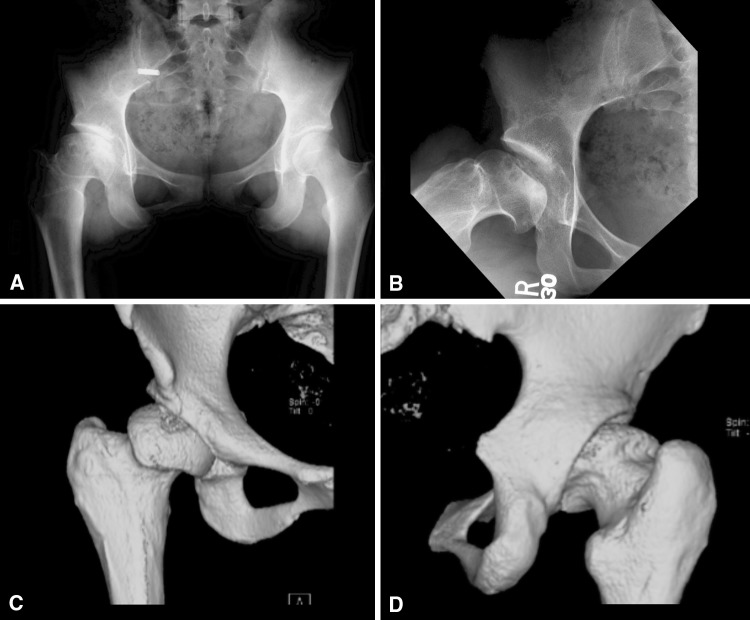

Fig. 1A–D.

A 21-year-old woman presenting with a 3-year history of progressive right hip pain. The patient was diagnosed with Perthes disease at a young age and previously underwent treatment including proximal femoral osteotomy with subsequent removal of hardware. AP pelvis (A), frog-lateral (B), and three-dimensional CT scans (C–D) demonstrate a Perthes deformity of the right hip with central osteochondral defect.

Preoperative radiographs were taken using a standardized protocol [9] and consisted of an AP pelvis, frog-leg lateral, and false-profile [6] views. The radiographs were analyzed for all hips by one of the authors (JRR). The lateral center-edge angle [35], acetabular index, anterior center-edge angle [33], center-trochanteric distance [26], acetabulum-head index [17], Tönnis osteoarthritis grade [33], and the classification of Stulberg et al. [31] as modified by Herring et al. [16] were recorded. The lateral center-edge angle was used to determine the severity of acetabular dysplasia, and it was calculated using the AP view according to the technique described by Wiberg [35]. Previously defined cutoff values for lateral center-edge angle were used with measurements less than 20° considered acetabular dysplasia and measurements between 20° and 24.9° considered borderline acetabular dysplasia [8]. Acetabular index (or Tönnis angle) represents the horizontal orientation of the weightbearing zone (sourcil) of the acetabulum [33]. This was measured on the AP pelvic radiograph and classified as normal (0°–10°), increased (> 10°), or decreased (< 0°). The anterior center-edge angle was calculated from the false-profile radiograph and was classified as normal (≥ 20°) or dysplastic (< 20°) [18]. The center-trochanteric distance indicates whether the tip of the greater trochanter is above or below the center of the femoral head. It is the vertical distance from the center of the femoral head to the tip of the greater trochanter along the femoral shaft axis [26]. Given the femoral head deformity in this group of patients, the center was defined as the intersection of the longest and shortest diameters of the femoral head. A negative value indicates the tip of the trochanter is proximal to the center of the femoral head. Values ranging from −1.1 to 1.0 cm are considered normal, whereas less than −1.7 cm are considered pathologic. Values between −1.2 cm and −1.7 cm are considered controversial [26]. Acetabulum-head index is a measurement that is used to assess the lateral subluxation of the hip. This was measured according to the technique described by Heyman and Herndon [17]. This is calculated as the ratio of the distance from the medial side of the femoral head to the edge of the acetabulum over the largest diameter of the femoral head along a parallel line to the first measurement. An acetabulum-head index less than 0.80 is considered abnormal [23, 25]. To assess the intraobserver reliability of these radiographic measurements, 10 radiographs were remeasured and showed an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.98 for the Tönnis angle, 0.99 for the lateral center-edge angle, 0.99 for the anterior center-edge angle 1.0, and 0.98 for the acetabulum-head index.

Using all radiographs, the degree of osteoarthritis present in each hip was determined with the use of the Tönnis classification system. As defined by Tönnis, grades of osteoarthritis ranged from 0 to 3 with Grade 0 indicating no signs of osteoarthritis; Grade 1, increased sclerosis of the head and acetabulum, slight joint-space narrowing, and slight lipping at the joint margins; Grade 2, small cysts in the head or acetabulum or moderate joint-space narrowing; and Grade 3, large cysts in the head or acetabulum, joint-space obliteration or severe joint-space narrowing, severe deformity of the femoral head, or evidence of necrosis [33]. With strict application of this grading system, loss of femoral head sphericity would result in a Grade 2 or 3 classification for all hips. However, in this subgroup of hips, we excluded these criteria given that all cases by definition have femoral head asphericity. The final Tönnis grade was determined on the basis of the single view with the highest degree of osteoarthritic change. For statistical analysis, Grade 2 osteoarthritis was considered advanced radiographic osteoarthritis. A modified classification system of Stulberg et al. [31] reported by Herring et al. [16] was used with Stulberg Class I indicating a normal hip; Stulberg Class II, femoral head sphericity fitting within 2 mm of each other on the AP and frog-leg lateral; Stulberg Class III, aspherical femoral head by more than 2 mm on either view; Stulberg Class IV, at least 1 cm of flattening of the femoral head and acetabulum; and Stulberg Class V, at least 1 cm of flattening of the femoral head and a normal acetabulum. The kappa values for remeasuring these values were 1.0 for the osteoarthritis grade and 1.0 for the modified classification of Stulberg et al.

All surgeries were performed by one of two authors (PLS, JCC) using the surgical dislocation technique as described by Ganz et al. [14] with a trochanteric flip osteotomy. After the arthrotomy was performed, the hip motion was assessed to visualize any pathologic impingement between the femur and the acetabulum. After dislocation, the chondral surfaces (acetabulum and femoral head) and the acetabular labrum were carefully inspected and all abnormalities documented (Fig. 2). Labral tears were classified by involvement of anterior, superolateral, and posterior regions of the acetabular rim [7]. Labral tear length was estimated intraoperatively using a 5-mm arthroscopic probe. Labral tear type was classified according to Beck et al. [3], where Grade 1 = normal labrum (macroscopically sound labrum), Grade 2 = degeneration (thinning or localized hypertrophy, fraying, discoloration), Grade 3 = full-thickness tear (complete avulsion from the acetabular rim), Grade 4 = detachment (separation between acetabular and labral cartilage, preserved attachment to bone), and Grade 5 = ossification (osseous metaplasia, localized or circumferential). Acetabular chondromalacia was classified by location, severity, and size. Location was identified as one of six sextants of the acetabulum: anterior central, anterior peripheral, superolateral central, superolateral peripheral, posterior central, and posterior peripheral. Severity of chondral injury was determined using the Beck classification [3] in which Grade 1 = normal cartilage (macroscopically sound cartilage), Grade 2 = malacia (roughening of surface, fibrillation), Grade 3 = debonding (loss of fixation to the subchondral bone, macroscopically sound cartilage; carpet phenomenon), Grade 4 = cleavage (loss of fixation to the subchondral bone; frayed edges, thinning of the cartilage, flap), and Grade 5 = defect (full-thickness defect, complete loss of cartilage). Size was again estimated using an intraoperative ruler. Various techniques were used to treat the labral and chondral pathology through the surgical dislocation approach (Table 1). At least one adjunctive surgical procedure was performed in all cases (Table 2). Additionally, 10 (28%) of the hips were treated with a combined periacetabular osteotomy for acetabular dysplasia and associated instability.

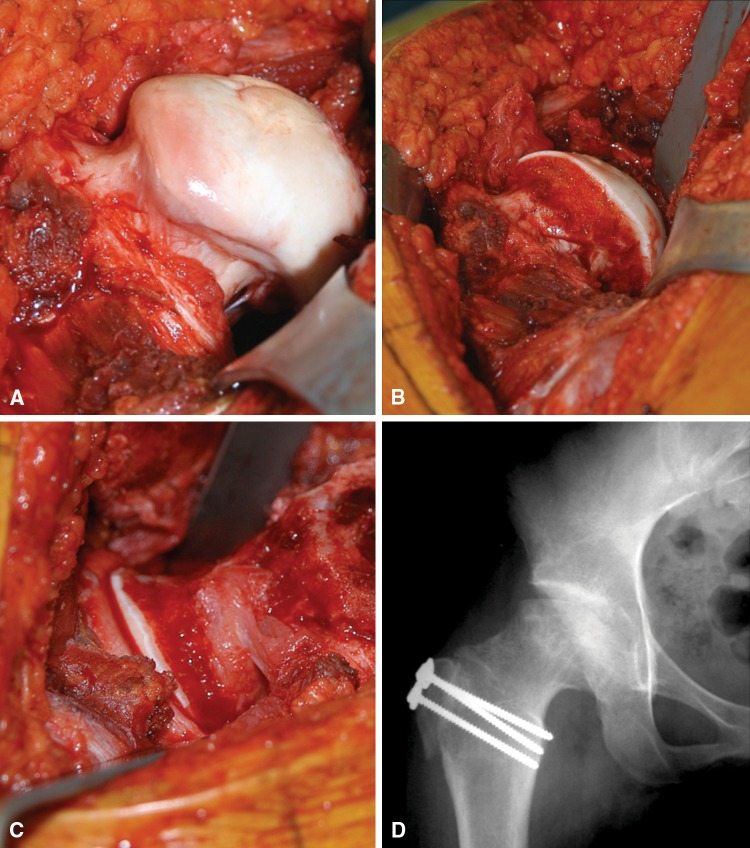

Fig. 2A–D.

The patient was treated with surgical dislocation and at the time of surgery was noted to have an unstable, loose chondral flap that was débrided, an anterolateral labral tear that was repaired, and a prominent femoral head-neck junction (A) that underwent an osteochondroplasty. (B–C) A trochanteric advancement and relative femoral neck lengthening was also part of relieving the extraarticular impingement. (D) She has an excellent clinical result at 5 years.

Table 1.

Intraoperative classifications of intraarticular disease patterns

| Disease classification | Number of hips | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Labral classification* | ||

| Detachment | 18 | 52.9 |

| Degeneration | 4 | 11.8 |

| Ossification | 3 | 8.8 |

| Full thickness | 1 | 2.9 |

| Normal | 8 | 23.5 |

| Hypertrophic | 22 | 64.7 |

| Acetabular chondral classification* | ||

| Normal | 14 | 41.2 |

| Malacia | 7 | 20.6 |

| Debonding | 3 | 8.8 |

| Cleavage | 7 | 20.6 |

| Defect | 3 | 8.8 |

| Femoral head chondral classification | ||

| Normal | 7 | 19.4 |

| Malacia | 17 | 47.2 |

| Debonding | 0 | 0 |

| Cleavage | 3 | 8.3 |

| Defect | 9 | 25.0 |

| Other intraarticular disease patterns | ||

| Synovitis | 22 | 61.1 |

| Hypertrophic capsule | 16 | 44.4 |

| Atrophic capsule | 2 | 5.6 |

| Loose bodies | 4 | 11.1 |

| Ligamentum teres tear | 11 | 30.6 |

* The labrum and acetabular cartilage were unable to be fully visualized in two hips and were thus removed from the percentage calculation.

Table 2.

Preoperative radiographic findings

| Measurement | Category | Number of hips | Percent | Measurement | Numerical range | Category | Number of hips | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stulberg | Class I | 2 | 5.6 | LCEA | < 20 | Dysplasia | 21 | 58.3 |

| Class II | 8 | 22.2 | 20–24.9 | Borderline | 1 | 2.8 | ||

| Class III | 10 | 27.8 | 25–35 | Normal | 11 | 30.6 | ||

| Class IV | 14 | 38.9 | > 35 | Overcoverage | 3 | 8.3 | ||

| Class V | 2 | 5.6 | ||||||

| Acet Inc | < 0 | Overcoverage | 2 | 5.6 | ||||

| Tönnis | Grade 0 | 8 | 22.2 | 0–10 | Normal | 11 | 30.6 | |

| Grade 1 | 16 | 44.4 | > 10 | Dysplasia | 23 | 63.9 | ||

| Grade 2 | 12 | 33.3 | ||||||

| Grade 3 | 0 | ACEA* | < 20 | Dysplasia | 22 | 61.1 | ||

| ≥ 20 | Normal | 11 | 30.6 | |||||

| AHI | < 0.80 | 25 | 69.4 | |||||

| ≥ 0.80 | 11 | 30.6 | CTD | < −1.7 | Pathologic | 21 | 58.3 | |

| −1.2 to −1.7 | Controversial | 7 | 19.4 | |||||

| −1.1 to 1.0 | Normal | 8 | 22.2 |

* Three hips did not have a false-profile radiograph performed and thus were unable to have the ACEA calculated. Acetabular dysplasia was defined as LCEA < 20° and borderline dysplasia 20°–24°; AHI = acetabulum-head index; LCEA = lateral center-edge angle; Acet Inc = acetabular inclination; ACEA = anterior center-edge angle; CTD = center-trochanteric distance.

All patients had an operative note describing the status of the labrum and the articular surfaces (acetabulum and femoral head) and a postoperative disease classification study sheet. The operative data were collected prospectively from a standardized data worksheet that was filled out by the surgeon at completion of the operation.

Statistical analysis was performed to identify differences in intraarticular disease findings (labral and chondral disease) according to clinical characteristics and radiographic parameters. Labral abnormalities were analyzed according to the presence of a tear as well as the presence of a tear greater than 20 mm. Chondral disease of the acetabulum and femoral head was classified as present/absent as well as moderate-severe disease. These moderate to severe lesions were classified as either Beck Grade 4 cleavage lesions, in which the cartilage was detached from the underlying bone, or Beck Grade 5 full-thickness defects [3]. Clinical characteristics included age and sex, whereas radiographic parameters included Stulberg classification, lateral center-edge angle, anterior center-edge angle, acetabular index, Tönnis grade, center-trochanteric distance, and acetabulum-head index. For categorical variable, we determined differences in the presence of intraarticular disease (for example, presence/absence of moderate-severe acetabular chondromalacia) between two groups based on clinical/radiographic parameter (for example, presence/absence acetabular dysplasia by lateral center-edge angle) using chi square (or Fisher’s exact test). Similarly for continuous variables, differences in the presence of intraarticular disease relative to a clinical/radiographic parameter (for example, age) were analyzed using the Student’s t-test. Statistical testing was performed using SPSS software (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Labral abnormalities were identified in 26 hips (76%; Table 3), whereas eight hips (24%) had a normal labrum. Two hips had incomplete visualization of the labrum and were thus unable to be classified. Labral disease was most common in the anterior and superolateral regions in 74% and 47% of hips, respectively. A total of 58% of labral lesions spanned both the anterior and superolateral regions. Posterior labral disease was noted in addition to or in continuity with an anterior/superolateral labral tear in four hips (12%). There were no isolated posterior labral tears. Labral tear size ranged from 5 mm to 60 mm among the hips with an average of 23.6 mm. Acetabular chondromalacia was observed in over half of the hips (n = 20 [59%]; Table 1) with malacia and debonding most common. These lesions were primarily located at the anterior (38%) and superolateral (47%) labrochondral junctions. Sixty-five percent of chondral lesions spanned both the anterior and superolateral regions. The average surface area involved for acetabular cartilage lesions was 167 mm2 (range, 50–350 mm2). The posterior acetabular articular cartilage was involved in four hips (12%). One hip had a localized lesion in the posterior central acetabular compartment and another hip had malacia spanning both the superolateral central and posterior central regions. Combined acetabular articular cartilage lesions and labral disease were observed in 15 hips (44%). Femoral head chondromalacia was observed in over 80% of hips (29 hips [81%]) with malacia most common. The average surface area involved was 390 mm2 (range, 50–1600 mm2). One hip (3%) was without labral or articular cartilage damage.

Table 3.

Surgical treatment of intraarticular disease

| Acetabulum | Femoral head | Labrum | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 20 (% total) | N = 29 (% total) | N = 26 (% total) | ||||||

| None | 10 | 50.0% | None | 19 | 65.5% | Repair | 17 | 65.4% |

| Chondroplasty | 7 | 35.0% | Microfracture | 4 | 13.8% | Partial Resection | 5 | 19.2% |

| Microfracture | 3 | 15.0% | Chondroplasty | 3 | 10.3% | None | 4 | 15.4% |

| ORIF | 3 | 10.3% | ||||||

| Resection | 1 | 3.4% | ||||||

| Mosaicplasty | 1 | 3.4% | ||||||

N designates the number of hips that were noted to have any disease at the time of surgery; % represents the portion of the diseased hips that underwent treatment; ORIF = reduction and fixation of an osteochondral fragment.

Male sex was associated with severe chondromalacia of either the acetabulum and/or femoral head (64% versus 27%; p = 0.042), the presence of femoral head chondromalacia (92% versus 55%; p = 0.018), and advanced radiographic osteoarthritis, defined as Tönnis Grade 2 (44% versus 9%; p = 0.043) (Table 4). Patient age was not associated with any disease patterns. Radiographic evidence of acetabular dysplasia was present on either the AP pelvis or false-profile radiographs in 28 hips (78%) based on the three selected parameters (lateral center-edge angle, acetabular inclination, and/or anterior center-edge angle). The center-trochanteric distance on average measured −2.2 (range, −0.3 to −4.7). The Tönnis grades of osteoarthritis ranged from 0 to 2 with the majority (78%) having Grade 1 or 2 osteoarthritis. Eighty-nine percent of the hips were classified as Stulberg Class II, III, or IV (Table 5). The mean acetabulum-head index measured 0.68 (range, 0.20–0.91). Twenty-five hips (69%) had an acetabulum-head index less than 0.80, which has been previously described as abnormal [21, 22]. A Stulberg classification of 3 or greater was associated with moderate to severe acetabular chondromalacia (42% versus 0%; p = 0.017) as well as advanced radiographic arthritis (46% versus 0%; p = 0.015). Lateral center-edge angle (≥ 20°) was associated with severe chondromalacia (38% versus 73%; p = 0.037) and radiographic osteoarthritis (19% versus 53%; p = 0.031). Acetabular inclination < 15° correlated with severe chondromalacia (23% versus 70%; p = 0.007). Center-trochanteric distance < −1.7 was associated with labral tears (90% versus 57%; p = 0.042). The anterior center-edge angle and acetabulum-head index did not correlate with the presence of intraarticular abnormalities.

Table 4.

Univariate analysis for the presence of intraarticular disease

| Intraarticular disease | Male | Female | p value | Age ≤ 20 years | Age > 20 years | p value | Stulberg 1 or 2 | Stulberg 3, 4, or 5 | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chondromalacia present | n = 25 Number (%) |

n = 11 Number (%) |

n = 26 Number (%) |

n = 10 Number (%) |

n = 10 Number (%) |

n = 26 Number (%) |

|||

| Acetabular and/or femur | 16 (64.0) | 3 (27.3) | 0.042 | 13 (50.0) | 6 (60.0) | 0.717 | 5 (50.0) | 14 (53.8) | 1.000 |

| Acetabulum chondromalacia | n = 23 | n = 11 | n = 25 | n = 9 | n = 10 | n = 24 | |||

| Any present | 20 (58.8) | 7 (63.6) | 0.495 | 15 (60.0) | 5 (55.6) | 1.000 | 3 (30.0) | 17 (70.8) | 0.054 |

| Moderate-severe | 8 (34.8) | 2 (18.2) | 0.283 | 7 (28.0) | 3 (33.3) | 1.000 | 0 (0) | 10 (41.7) | 0.017 |

| Femoral head chondromalacia | n = 25 | n = 11 | n = 26 | n = 10 | n = 10 | n = 26 | |||

| Any present | 23 (92.0) | 6 (54.5) | 0.018 | 23 (88.5) | 6 (60.0) | 0.076 | 9 (90.0) | 20 (76.9) | 0.645 |

| Moderate-severe | 10 (40.0) | 2 (18.2) | 0.187 | 9 (34.6) | 3 (30.0) | 1.000 | 5 (50.0) | 7 (26.9) | 0.247 |

| Labral tear | n = 23 | n = 11 | n = 25 | n = 9 | n = 10 | n = 24 | |||

| Any present | 18 (78.3) | 8 (72.7) | 0.519 | 19 (76.0) | 7 (77.8) | 1.000 | 9 (90.0) | 17 (70.8) | 0.385 |

| Large tear (> 2 cm) | 9 (39.1) | 1 (9.1) | 0.072 | 6 (24.0) | 4 (44.4) | 0.230 | 1 (10.0) | 9 (37.5) | 0.215 |

| Radiographic osteoarthritis | n = 25 | n = 11 | n = 26 | n = 10 | n = 10 | n = 26 | |||

| Tönnis Grade ≥ 2 | 11 (44.0) | 1 (9.1) | 0.043 | 10 (38.5) | 2 (20.0) | 0.438 | 0 (0) | 12 (46.2) | 0.015 |

| Intraarticular disease | LCEA < 20° | LCEA > 20° | p value | Acet Incl ≤ 15 | Acet Incl > 15 | p value | CTD < -1.7 | CTD ≥ -1.7 | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 21 Number (%) |

n = 15 Number (%) |

n = 23 Number (%) |

n = 13 Number (%) |

n = 21 Number (%) |

n = 15 Number (%) |

||||

| Chondromalacia present (acetabulum and/or femur) | 8 (38.1) | 11 (73.3) | 0.037 | 16 (69.6) | 3 (23.1) | 0.007 | 10 (47.6) | 9 (60.0) | 0.463 |

| Acetabulum chondromalacia | n = 20 | n = 14 | n = 21 | n = 13 | n = 20 | n = 14 | |||

| Any present | 11 (55.0) | 9 (64.3) | 0.588 | 12 (57.7) | 8 (61.5) | 0.800 | 12 (60.0) | 8 (57.1) | 0.868 |

| Moderate-severe | 3 (15.0) | 7 (50.0) | 0.054 | 9 (42.9) | 1 (7.7) | 0.051 | 6 (30.0) | 4 (28.6) | 1.000 |

| Femoral head chondromalacia | n = 21 | n = 15 | n = 23 | n = 13 | n = 21 | n = 15 | |||

| Any present | 15 (71.5) | 14 (93.3) | 0.200 | 21 (91.3) | 8 (61.5) | 0.073 | 16 (76.2) | 13 (86.7) | 0.674 |

| Moderate-severe | 5 (23.8) | 7 (46.7) | 0.151 | 10 (43.5) | 2 (15.4) | 0.143 | 6 (28.6) | 6 (40.0) | 0.473 |

| Labral tear | n = 20 | n = 14 | n = 21 | n = 13 | n = 20 | n = 14 | |||

| Any present | 14 (70.0) | 12 (85.7) | 0.422 | 17 (81.0) | 9 (69.2) | 0.679 | 18 (90.0) | 8 (57.1) | 0.042 |

| Large tear (> 2 cm) | 4 (20.0) | 6 (42.9) | 0.252 | 7 (33.3) | 3 (23.1) | 0.704 | 6 (30.0) | 4 (28.6) | 1.000 |

| Radiographic osteoarthritis | n = 21 | n = 15 | n = 23 | n = 13 | n = 21 | n = 15 | |||

| Tönnis Grade ≥ 2 | 4 (19.0) | 8 (53.3) | 0.031 | 10 (43.5) | 2 (15.4) | 0.143 | 6 (28.6) | 6 (40.0) | 0.473 |

| Intraarticular disease | AHI < 0.80 | AHI ≥ 0.80 | p value | ACEA < 20 | ACEA ≥ 20 | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 25 Number (%) |

n = 15 Number (%) |

n = 22 Number (%) |

n = 11 Number (%) |

|||

| Any moderate-severe chondromalacia | 12 (48.0) | 7 (63.6) | 0.387 | 10 (45.5) | 6 (54.5) | 0.622 |

| Acetabulum chondromalacia | n = 24 | n = 10 | n = 21 | n = 10 | ||

| Any present | 15 (62.5) | 5 (50.0) | 0.704 | 14 (66.7) | 5 (50.0) | 0.447 |

| Moderate-severe | 7 (29.2) | 3 (30.0) | 1.000 | 6 (28.6) | 3 (30.0) | 1.000 |

| Femoral head chondromalacia | n = 25 | n = 11 | n = 22 | n = 11 | ||

| Any present | 19 (76.0) | 10 (90.9) | 0.400 | 16 (72.7) | 10 (90.9) | 0.378 |

| Moderate-severe | 8 (32.0) | 4 (36.4) | 1.000 | 5 (22.7) | 4 (36.4) | 0.438 |

| Labral tear | n = 24 | n = 10 | n = 21 | n = 10 | ||

| Any present | 18 (75.0) | 8 (80.0) | 1.000 | 16 (76.2) | 8 (80.0) | 1.000 |

| Large tear (> 2 cm) | 6 (25.0) | 4 (40.0) | 0.431 | 7 (33.3) | 3 (30.0) | 1.000 |

| Radiographic osteoarthritis | n = 25 | n = 11 | n = 22 | n = 11 | ||

| Tönnis Grade ≥ 2 | 7 (28.0) | 5 (45.5) | 0.446 | 7 (31.8) | 3 (27.3) | 1.000 |

LCEA = lateral center-edge angle; Acet Incl = acetabular inclination; CTD = center-trochanteric distance; AHI = acetabulum-head index.

Table 5.

Procedures performed through the surgical dislocation approach

| Surgical procedure | Number of hips | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Femoral osteochondroplasty | 36 | 100 |

| Trochanteric advancement | 33 | 91.7 |

| Relative femoral neck lengthening | 28 | 77.8 |

| Acetabular rim resection | 8 | 22.2 |

| PFO | 2 | 5.6 |

PFO = proximal femoral osteotomy.

Discussion

Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, both treated and untreated, can lead to residual hip deformity. When clinical symptoms are present and nonoperative management has failed, surgical treatment can be considered in this subgroup of patients. The residual deformity variably encompasses a prominent greater trochanter, a short femoral neck, aspheric femoral head, and associated acetabular dysplasia. These structural abnormalities are believed to alter the mechanical environment of the hip and put the hip at risk for progressive labrochondral and articular cartilage disease [2, 15, 20]. Nonetheless, it is unclear whether intraarticular disease patterns relate to clinical and radiographic factors. These data may impact surgical decision-making, preoperative planning, and may have prognostic importance. We therefore (1) determined the characteristics of intraarticular disease (labral, articular cartilage, osteochondral, and ligamentum teres lesions) associated with residual Perthes-like hip deformities; and (2) investigated the association of these intraarticular abnormalities with clinical characteristics and radiographic parameters of hip structure.

This study does have limitations. First, radiographic evaluation of Perthes deformities of the hip is complex, and the optimal image set to characterize these deformities has not been definitively established. We analyzed the AP pelvis, frog-leg lateral, and false-profile views to visualize the anterior and lateral aspects of the acetabulum as well as the entire proximal femur and femoral head. This combination of radiographs provides adequate information regarding structural hip anatomy but does not enable three-dimensional or dynamic analysis of the structural hip anatomy. Second, the intraarticular pathology that is present in these patients represents only the subgroup of patients who have early changes and are candidates for joint preservation surgery. We do not describe more advanced stages of intraarticular disease and therefore cannot comment on the patterns of disease progression or end-stage disease characteristics. Although this is a limitation, the subgroup of patients who would likely benefit from joint-preserving surgery is the focus of our study. Data on these patients are most important because they may impact treatment and prognostic assessment. The final limitation is that we have not reported clinical outcomes data relative to disease pattern. This will be the focus of future studies and is beyond the scope of this investigation [30, 32, 34].

We found labral disease in more than 75% (76%) of hips, acetabular chondromalacia in more than half (59%) of the hips, and femoral head chondromalacia in more than 80% (81%) of hips. Labrochondral disease was primarily localized to the anterior and superolateral acetabular rim. Shin et al. [29] reported on a series of 23 hips in 21 patients with pediatric hip diseases that were treated with surgical hip dislocation. Only four of these hips (17%) carried the diagnosis of Perthes disease. There was no further information in regard to intraoperative findings or rationale for operative decisions. Rebello et al. [27] retrospectively reviewed 15 Perthes hips that were treated using a surgical dislocation. Like in the previous study, there was no mention of the intraarticular disease patterns observed at the time of surgery. Anderson et al. [1] reviewed a series of 14 patients with an average followup of 45 months who underwent surgical hip dislocation with trochanteric advancement. Acetabular chondral pathology was noted in 43% of the hips, the majority of which were full-thickness lesions. Labral pathology was also noted in an additional 43% of the hips. Femoral head osteochondral defects were noted in 29% of the hips. Eijer et al. [12] reviewed a group of 12 hips in 11 patients surgically treated for residual Perthes disease. Nearly all of the patients had an MR arthrogram before the procedure with concern for labral and/or acetabular chondral disease, thus prompting surgical treatment. Ninety-two percent of these hips were noted to have a labral tear. Eighty-two percent of the hips with a labral tear also had an adjacent acetabular chondral lesion. One patient had diffuse acetabular chondromalacia. There was no mention of femoral head chondral disease patterns. In a series of nine, previously asymptomatic patients with Perthes disease, Roy [28] evaluated intraarticular findings of newly symptomatic hips with arthroscopy. Eight of these patients had previous hip surgery, including pelvic osteotomy, capsular release, and greater trochanter apophyseodesis. Nearly 90% of the hips had abnormalities noted during hip arthroscopy (eight of nine patients). Intraarticular findings included ligamentum teres tears, osteochondritis dissecans of the femoral head, labral tears, substantial synovitis, femoral head chondromalacia, and osteoarthritis. The patients who were analyzed in this investigation were all treated using an open surgical dislocation. We favor open treatment in Perthes deformities because it allows excellent visualization of hip mechanics and the opportunity for comprehensive structural corrections including head-neck osteoplasty, relative neck lengthening, trochanteric osteoplasty, and trochanteric advancement. We believe that arthroscopic treatment has substantial limitations in the dynamic assessment and structural corrections in Perthes deformities.

We demonstrated that male sex, a Stulberg classification of 3 or greater, and a pathologic center-trochanteric distance were statistically associated with an increased risk of intraarticular abnormalities. Male sex is reportedly independently associated with more severe intraarticular disease in a series of patients undergoing hip arthroscopy [24]. In contrast, acetabular dysplasia was associated with less severe chondromalacia. Although these three studies [1, 12, 28] presented basic data on intraarticular disease, none correlated these findings with clinical and radiographic parameters. In addition to documenting disease patterns in residual Perthes deformities, our data draw attention to the relationship of structural hip anatomy and intraarticular disease. Specifically, associated acetabular dysplasia (lateral center-edge angle < 20° and acetabulum-head index > 15°) correlated with less severe articular cartilage disease. This may indicate that the dysplastic acetabulum better accommodates the aspheric Perthes femoral head with less rim impingement and therefore is protective of the acetabular and femoral articular cartilage. Second, a higher trochanter was associated with acetabular labral disease. This suggests the negative biomechanical consequences of the high trochanter may be manifested by failure of the labrochondral junction. Collectively, these data suggest management of Perthes disease in the skeletally immature patient should avoid (if possible) acetabular overcoverage of the femoral head and a relatively high greater trochanter position.

In summary, symptomatic hips with residual Perthes-like structural deformities commonly have chondral lesions of the acetabulum and femoral head and labral tears. Male sex, a high trochanter, and joint incongruity are associated with more advanced intraarticular disease. Secondary acetabular dysplasia seems to protect the articular cartilage in that hips with acetabular dysplasia had less chondromalacia. Hip preservation surgeons should be aware of these disease characteristics and the associated risk factors. Future studies will investigate the impact of intraarticular disease patterns on clinical outcomes of hip preservation surgery.

Acknowledgments

We thank Debbie Long for assistance with the preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

The institution of one or more of the authors (JJN) has received, in any one year, funding from the Arthrex Hip Anatomical Study. One author (JCC) certifies that he has or may receive payments or benefits, in any one year, an amount less than $10,000, from Biomet (Warsaw, IN, USA). The institution of one of the authors (JCC) received research support from Zimmer, Inc (Warsaw, IN, USA) and the Curing Hip Disease Fund (St Louis, MO, USA).

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

References

- 1.Anderson LA, Erickson JA, Severson EP, Peters CL. Sequelae of Perthes disease: treatment with surgical hip dislocation and relative femoral neck lengthening. J Pediatr Orthop. 2010;30:758–766. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e3181fcbaaf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aronson J. Osteoarthritis of the young adult hip: etiology and treatment. Instr Course Lect. 1986;35:119–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beck M, Kalhor M, Leunig M, Ganz R. Hip morphology influences the pattern of damage to the acetabular cartilage: femoroacetabular impingement as a cause of early osteoarthritis of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:1012–1018. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B7.15203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beck M, Mast JW. The periacetabular osteotomy in Legg-Perthes-like deformities. Semin Arthroplasty. 1997;8:102–107. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beer Y, Smorgick Y, Oron A, Mirovsky Y, Weigl D, Agar G, Shitrit R, Copeliovitch L. Long-term results of proximal femoral osteotomy in Legg-Calve-Perthes disease. J Pediatr Orthop. 2008;28:819–824. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e31818e122b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Byrd JW, Jones KS. Prospective analysis of hip arthroscopy with 2-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2000;16:578–587. doi: 10.1053/jars.2000.7683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Byrd JW, Jones KS. Hip arthroscopy in athletes. Clin Sports Med. 2001;20:749–761. doi: 10.1016/S0278-5919(05)70282-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Byrd JW, Jones KS. Hip arthroscopy in the presence of dysplasia. Arthroscopy. 2003;19:1055–1060. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clohisy JC, Carlisle JC, Beaule PE, Kim YJ, Trousdale RT, Sierra RJ, Leunig M, Schoenecker PL, Millis MB. A systematic approach to the plain radiographic evaluation of the young adult hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(Suppl 4):47–66. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clohisy JC, Keeney JA, Schoenecker PL. Preliminary assessment and treatment guidelines for hip disorders in young adults. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;441:168–179. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000193511.91643.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clohisy JC, Nunley RM, Curry MC, Schoenecker PL. Periacetabular osteotomy for the treatment of acetabular dysplasia associated with major aspherical femoral head deformities. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:1417–1423. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eijer H, Podeszwa DA, Ganz R, Leunig M. Evaluation and treatment of young adults with femoro-acetabular impingement secondary to Perthes’ disease. Hip Int. 2006;16:273–280. doi: 10.1177/112070000601600406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eilert RE, Hill K, Bach J. Greater trochanteric transfer for the treatment of coxa brevis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;434:92–101. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000163474.74168.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ganz R, Gill TJ, Gautier E, Ganz K, Krugel N, Berlemann U. Surgical dislocation of the adult hip a technique with full access to the femoral head and acetabulum without the risk of avascular necrosis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83:1119–1124. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.83B8.11964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris WH. Etiology of osteoarthritis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1986;213:20–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herring JA, Kim HT, Browne R. Legg-Calve-Perthes disease. Part I: Classification of radiographs with use of the modified lateral pillar and Stulberg classifications. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:2103–2120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heyman CH, Herndon CH. Legg-Perthes disease; a method for the measurement of the roentgenographic result. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1950;32:767–778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lequesne M, de Seze [False profile of the pelvis. A new radiographic incidence for the study of the hip. Its use in dysplasias and different coxopathies] [in French] Rev Rhum Mal Osteoartic. 1961;28:643–652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Macnicol MF, Makris D. Distal transfer of the greater trochanter. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73:838–841. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.73B5.1894678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McAndrew MP, Weinstein SL. A long-term follow-up of Legg-Calve-Perthes disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66:860–869. doi: 10.2106/00004623-198466060-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moberg A, Hansson G, Kaniklides C. Acetabulum-head index in children with normal hips: a radiographic study of 154 hips. J Pediatr Orthop B. 1999;8:268–270. doi: 10.1097/00009957-199910000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moberg A, Hansson G, Kaniklides C. Acetabulum-head index measured on arthrograms in children with Legg-Calve-Perthes disease. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2000;9:252–256. doi: 10.1097/01202412-200010000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mose K, Hjorth L, Ulfeldt M, Christensen ER, Jensen A. Legg Calve Perthes disease. The late occurence of coxarthrosis. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl. 1977;169:1–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nepple JJ, Carlisle JC, Nunley RM, Clohisy JC. Clinical and radiographic predictors of intra-articular hip disease in arthroscopy. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39:296–303. doi: 10.1177/0363546510384787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Novais EN, Clohisy J, Siebenrock K, Podeszwa D, Sucato D, Kim YJ. Treatment of the symptomatic healed Perthes hip. Orthop Clin North Am. 2011;42:401–417. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Omeroglu H, Ucar DH, Tumer Y. [A new measurement method for the radiographic assessment of the proximal femur: the center-trochanter distance] [in Turkish] Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2004;38:261–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rebello G, Spencer S, Millis MB, Kim YJ. Surgical dislocation in the management of pediatric and adolescent hip deformity. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:724–731. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0591-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roy DR. Arthroscopic findings of the hip in new onset hip pain in adolescents with previous Legg-Calve-Perthes disease. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2005;14:151–155. doi: 10.1097/01202412-200505000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shin SJ, Kwak HS, Cho TJ, Park MS, Yoo WJ, Chung CY, Choi IH. Application of Ganz surgical hip dislocation approach in pediatric hip diseases. Clin Orthop Surg. 2009;1:132–137. doi: 10.4055/cios.2009.1.3.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Snow SW, Keret D, Scarangella S, Bowen JR. Anterior impingement of the femoral head: a late phenomenon of Legg-Calve-Perthes’ disease. J Pediatr Orthop. 1993;13:286–289. doi: 10.1097/01241398-199305000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stulberg SD, Cooperman DR, Wallensten R. The natural history of Legg-Calve-Perthes disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981;63:1095–1108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tanzer M, Noiseux N. Osseous abnormalities and early osteoarthritis: the role of hip impingement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;429:170–177. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000150119.49983.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tönnis D. Congenital Dysplasia and Dislocation of the Hip in Children and Adults. Berlin, Germany, New York, NY, USA: Springer; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wenger DR, Kishan S, Pring ME. Impingement and childhood hip disease. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2006;15:233–243. doi: 10.1097/01202412-200607000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wiberg G. Studies on dysplastic acetabula and congenital sybluxation of the hip joint. With special reference to the complication of osteoarthritis. Acta Chir Scand Suppl. 1939;58:7–38. [Google Scholar]