Abstract

Background:

Low expression levels of S100A11 proteins were demonstrated in the placental villous tissue of patients with early pregnancy loss, and S100A11 is a Ca2+-binding protein that interprets the calcium fluctuations and elicits various cellular responses.

Objectives:

The objective of the study was to determine S100A11 expression in human endometrium and its roles in endometrial receptivity and embryo implantation.

Methods:

S100A11 expression in human endometrium was analyzed using quantitative RT-PCR, Western blot, and immunohistochemical techniques. The effects of S100A11 on embryo implantation were examined using in vivo mouse model, and JAr (a human choriocarcinoma cell line) spheroid attachment assays. The effects of endometrial S100A11 on factors related to endometrial receptivity and immune responses were examined. Using a fluorescence method, we examined the changes in cytosolic Ca2+ and Ca2+ release from intracellular stores in epidermal growth factor (EGF)-treated endometrial cells transfected with or without S100A11 small interfering RNA.

Results:

S100A11 was expressed in human endometrium. S100A11 protein levels were significantly lower in endometrium of women with failed pregnancy than that in women with successful pregnancy outcomes. The knockdown of endometrial S100A11 not only reduced embryo implantation rate in mouse but also had adverse effects on the expression of factors related to endometrial receptivity and immune responses in human endometrial cells. Immunofluorescence analysis showed that S100A11 proteins were mainly localized in endoplasmic reticulum. The EGF up-regulated endometrial S100A11 expression and promoted the Ca2+ uptake and release from Ca2+ stores, which was inhibited by the knockdown of S100A11.

Conclusions:

Endometrial S100A11 is a crucial intermediator in EGF-stimulated embryo adhesion, endometrium receptivity, and immunotolerance via affecting Ca2+ uptake and release from intracellular Ca2+ stores. Down-regulation of S100A11 may cause reproductive failure.

Calcium ions (Ca2+) play a vital role as universal second messengers that mediate the effects of a variety of extracellular signals, such as hormones, neurotransmitters, growth factors, etc. (1). Two main Ca2+ mobilizing systems coexist in the cells: Ca2+ influx from the extracellular medium and Ca2+ release from internal stores. Cytosolic free Ca2+ will bind to calcium-sensing proteins including S100 proteins, calmodulin, and troponin, which interpret the calcium fluctuations and elicit various cellular responses. The importance and function of Ca2+ in fertilization, early embryo development, and implantation have been well studied (2, 3). Our previous study showed that attenuation of cytosolic Ca2+ levels in human endometrial cells by inhibiting large conductance calcium-activated potassium channels was associated with low endometrial receptivity and reduced embryo implantation (4). However, regulation of Ca2+ homeostasis in uterine endometrium is not yet fully understood, and its molecular mechanisms require further elucidation.

The effects of Ca2+ are mediated by a host of Ca2+-binding proteins that serve as Ca2+ sensors. In general, Ca2+-binding proteins that function as sensors undergo conformational changes upon Ca2+ binding that allow them to interact with downstream effectors (5, 6). The most common Ca2+-binding structural motif in proteins is the EF-hand, a helix-loop-helix structural domain (5, 6). S100A11 is a member of the S100 protein family containing two EF-hand calcium-binding motifs (7, 8) and is expressed in various tissues at different levels (9, 10). Like other subtypes of S100 proteins, one of the functions of S100A11 is to act as calcium-signaling molecules by converting changes in cellular Ca2+ levels to a variety of biological responses (11). A high local calcium concentration will induce the conformational change in S100A11, which promotes membrane fusion required for enlargeosome vesicle formation, a requirement in models for the maintenance of membrane lesions or for vesiculation processes used in endo/exocytosis (11, 12).

It has been shown that the expression of S100A11 in the placental villous tissue of early pregnancy loss patients was significantly down-regulated, suggesting the involvement of S100A11 in the embryo implantation and early pregnancy maintenance (13). Embryo implantation is a process in embryo attachment to the endometrium and penetration into the endometrial stromal compartment (14). During implantation, some hormones and cytokines, including epidermal growth factor (EGF), progesterone, and estrogen, contribute to the cross talking between embryo and uterine endometrium and facilitate the process of embryo invasion and adhesion (15–17). The cumulative evidence suggests that the expression of EGF and EGF receptor (EFGR) in the uterus or embryo is important for implantation and embryo development (18, 19). It was found that the implantation rate of developing blastocysts was significantly higher in the presence of exogenous EGF compared with the control blastocysts in vitro (20). In porcine uteri, the EGF and EGFR were highly expressed around the window of implantation (21). Ca2+ has been shown to mediate the effects of activation of EGFR by EGF (22), and S100A11 is one of target proteins of EGF (23). Based on the evidence cited above, we hypothesize that endometrial S100A11 might play an important role in embryo implantation including EGF-promoted embryo implantation via regulating cytosolic Ca2+ homeostasis.

In the present study, we examined the expression of S100A11 in human endometrium and the effects of S100A11 on embryo implantation in the absence or presence of exogenous EGF. Our data clearly demonstrated that S100A11 played important roles in the EGF-mediated intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis in human endometrial cells, embryo implantation and pregnancy outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Patients and sample collection

Ethical approval for this project was granted by the Ethics Committee of the School of Medicine, Zhejiang University. A written informed consent was obtained from each subject before tissue collection. A total of 38 women of reproductive age volunteered for this study. They were healthy and not taking any drugs in past 6 months. Their mean age was 29.47 ± 0.47 yr.

The endometrial samples were collected from women who attended Women's Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University. The midsecretory endometrial samples were collected from women who underwent in vitro fertilization (IVF) and embryo transfer (ET) treatment because of infertility due to tubule pathology without hydrosalpinges and were obtained with a biopsy catheter during the spontaneous menstrual cycle at d 21 for diagnostic purposes before IVF-ET cycle (n = 38). None of these patients had received hormone therapy in the past 6 months. Shortly after collection, some endometrial tissues were stored at −70 C for RNA and protein extraction.

Cell culture

Human endometrial epithelial cells (Ishikawa cells) were maintained in phenol red RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (vol/vol) and 100 U/ml penicillin and streptomycin at 37 C in 95% CO2. When the cells was confluent to 40–50%, the medium was replaced of phenol red-free RPMI 1640 supplemented with 0.5% charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum, and different agents including EGF (20 ng/ml; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), 17β-estradiol (E2; 7.14 nmol/liter; Sigma-Aldrich), progesterone (P4; 63.5 nmol/liter; Sigma-Aldrich), and human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG; 0.04∼40 IU/ml, Riyue Medicine Co., Hangzhou, China) were added into the culture medium at different concentrations for certain duration according to the experiment purposes.

Immuohistochemical analysis

The samples were sectioned at 4 μm, blocked in 1% BSA, and incubated with rabbit anti-S100A11 primary antibody (1:2000; Proteintech Group, Chicago, IL) for 2 h at room temperature. After incubation with goat polyclonal antirabbit secondary antibody (DakoCytomation, Glostrup, Denmark) for 60 min, the sections were reacted with diaminobenzidine (DakoCytomation) and counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated, and mounted in distrene dibutylphthalate xylene.

Quantitative real time-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis

Total RNA was extracted from scraped cells using the Trizol reagents and reverse-transcribed method according manufacturer's instructions as described before (4). qRT-PCR was carried out in Applied Biosystems 7500 Fast (Applied Biosystems Inc., Carlsbad, CA). Primer sequences used in this study are listed in Table 1. Data were analyzed by the comparative threshold cycle method (4).

Table 1.

Sequences of primer sets for qRT-PCR

| Gene | Forward primer (5′-3′) | Reverse primer (5′-3′) | Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| S100A11 | GTCCCTGATTGCTGTCTTCC | ACCAGGGTCCTTCTGGTTCT | 130 |

| LIF | TCTGAAGTGCAGCCCATAATGAAG | TATGGCACAGGTGGCGTTG | 126 |

| DDK-1 | CATCAGACTGTGCCTCAGGA | CCACAGTAACAACGCTGGAA | 145 |

| Claudin-4 | GCCTGGAGGATGAAAGCG | AAGTCTTGGATGATGTTGTGGG | 121 |

| Integrin-β3 | TGACGAAAATACCTGCAACCG | GCATCCTTGCCAGTGTCCTTAA | 78 |

| OLFML1 | TGGGGAGGGTCCGCATGTGT | TCAAGGGCTCCGGTGGTGCT | 251 |

| IL-15 | CAGAAGCCAACTGGGTGAATGTAA | TTGCATCTCCGGACTCAAGTG | 180 |

| IL-4 | TCTGTGCACCGAGTTGACCGT | TGCTGTGCAGTCGCACCCAG | 150 |

| IL-16 | AGAAAAGCCTGGAAAACTAGAAG | GCAGATTTCTTGGTCATTGG | 141 |

| EGFR | ACCACGTACCAGATGGATGTGAAC | GAGCCGTGATCTGTCACCACATA | 101 |

| IL-12α | GGCCTGTTTACCATTGGA | TGCCAGCATGTTTTGATCTA | 235 |

| TLR2 | CTTCATAAGCGGGACTTCATTC | CTCCAGGTAGGTCTTGGTGTTC | 270 |

| Myd88 | TAAGAAGGACCAGCAGAGCC | CATGTAGTCCAGCAACAGCC | 200 |

| GAPDH | CAGGGCTGCTTTTAACTCTGG | TGGGTGGAATCATATTGGAACA | 102 |

Western immunoblot analysis

Cells were collected and washed with PBS three times and then were homogenized in 1× radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer containing 0.1 mmol/liter PBS, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 0.05% deoxycholate, and protease inhibitors (100 μg/ml leupeptin and 100 μg/ml phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). The homogenate was incubated on ice for 30 min and was then centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 15 min. The protein concentration in the supernate was determined by a Bradford assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Samples at 50 μg/lane were separated on a 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel and transferred to Protran Immun-Blot nitrocellulose transfer membrane (Schleicher & Schuell Bioscience GmbH, Dassel, Germany). Membranes were overnight incubated with rabbit anti-S100A11 antibody (1:500), mouse monoclonal anti-IL-15 antibody (1:500; Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA), goat polyclonal antileukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) antibody (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), mouse monoclonal anti-EGFR antibody (1:800; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and mouse monoclonal antiactin antibody (1:5000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at 4 C. After several washes with Tris-buffered saline and 0.2% Tween 20, the membranes were incubated with the appropriate secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. The bound antibody was detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection reagent (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

In vivo and in vitro S100A11-specific small interfering RNA (siRNA) interference

All animal experiments were performed according to the appropriate guidelines for animal used approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of School of Medicine, Zhejiang University. Female ICR mice aged 8–9 wk in estrus were bred with male ICR mice, and the morning when vaginal plugging was observed was designated as d 0.5 postcoitus (p.c.). The successfully bred females were separated from males. Mice on d 2.5 p.c. were anesthetized and subjected to laparotomy to expose the uterus. We injected 15 μl/horn of S100A11 specific siRNA suspension (10 nm; Ambion, Carlsbad, CA) or scrambled siRNA suspension (10 nm; Ambion) slowly into the uterine cavity using a 30-gauge needle. After transfection with specific siRNA targeting S100A11 for 48 h, we harvested the endometrium from some ICR mice for protein extraction and found that S100A11 protein levels in the endometrium treated with S100A11 siRNA was reduced by 47.4% (Fig. 1D). On d 6.5 p.c., the uteri were removed and the implantation sites were photographed.

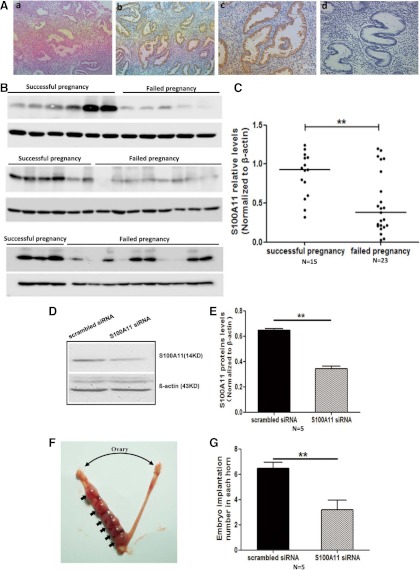

Fig. 1.

Association of low expression levels of S100A11 with poor pregnancy outcomes in humans and mice. Immunohistochemical analysis showed expression and localization of S100A11 in the glandular and luminal epithelia of human midsecretory endometrium. Aa, Negative control, ×200; Ab, ×100; Ac, ×200; Ad, isotype control. B and C, Expression of S100A11protein in human endometria from infertile women who were stratified into successful (n = 15) and failed pregnancy (n = 23) subgroups according to IVF outcomes. D and E, S100A11 protein levels in endometria of mice injected with scrambled siRNA (n = 5) and specific siRNA targeting S100A11 (n = 5), respectively. F and G, Embryo implantation rate in mice injected with scrambled siRNA (n = 5) and specific siRNA targeted S100A11 (n = 5), respectively. Data are presented as mean ± se. **, P < 0.01 compared with the corresponding controls.

In vitro transfection was performed as described before (4). Ishikawa cells were plated in a six-well plate at a density of 2 × 105/ml. When confluence was 40%, Ishikawa cells were transfected with S100A11 siRNA in lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at a final concentration of 6 nm. S100A11 protein levels in Ishikawa cells treated with S100A11 siRNA for 24 and 48 h were reduced by 50.3 and 86.3%, respectively (Fig. 2C). The experiments were performed after siRNA treatment for 24 h.

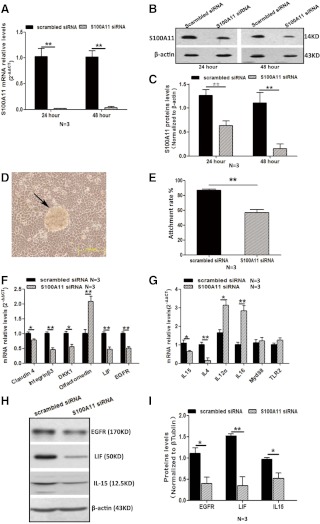

Fig. 2.

Effects of S100A11 knockdown in endometrial cells on JAr spheroid attachment and factors related to endometrial receptivity and immune responses. S100A11 mRNA levels (A) and protein (B and C) levels in Ishikawa cells treated with scrambled siRNA or targeted specific siRNA S100A11. D and E, JAr spheroid attachment rate in Ishikawa cells treated with scrambled siRNA and specific siRNA targeting S100A11. Arrow in D indicates the JAr spheroid attached to human endometrial cells. F, The mRNA levels of factors related to endometrial receptivity in Ishikawa cells treated with scrambled siRNA or specific siRNA targeting S100A11. G, The mRNA levels of factors related to immune responses. H and I, The protein levels of selected factors related to embryo implantation in endometrial cells treated with scrambled siRNA or specific siRNA targeting S100A11. Data are presented as mean ± se. * or **, P < 0.05 or P < 0.01, compared with the corresponding controls. N, Number of repeated experiments.

JAr spheroid-endometrial cell attachment assay

We used multicellular spheroids of human choriocarcinoma JAr cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA; HTB 144) as an in vitro attachment model that were applied to endometrial cell monolayers as described before (4). When Ishikawa cells were transfected with scrambled siRNA or S100A11 siRNA for 24 h, the JAr spheroids were transferred onto the surface of a confluent monolayer of Ishikawa cells. The cultures were maintained in the culture medium (RPMI 1640 medium + 10% fetal bovine serum + 10 nm E2 + 1 μm P4) for 1 h. Nonadherent spheroids were removed by centrifugation of the six-well plates with the cell surface facing down at 10 × g for 10 min. We counted the attached spheroids under a light microscope and expressed the result as the percentage of the total number of spheroids used.

Immunofluorescence and immune electron microscopy detection

Human endometrial cells were blocked in 1% BSA and then incubated with a 1:100 dilution of anti-S100A11 and antiprotein disulfide isomerase A3 (PDIA3; Proteintech Group) antibodies at 4 C overnight. They were incubated with a 1:200 dilution of Alex Fluor488 goat antimouse IgG and Fluor 570 goat antirabbit IgG (Invitrogen) for 2 h.

In the experiment using immune electron microscopy, Ishikawa cells were digested by 0.25% trypsin and were washed with PBS and fixed for 1 h with 4% paraformaldehyde and 0.4% glutaraldehyde in PBS. Samples were dehydrated with ethanol up to 96% followed by infiltration with LR White acrylic resin, hard grade, and embedding under a layer of Aclar film. Using an UltraCut S ultramicrotome (Reichert, Heidelberg, Germany), thin sections were prepared and placed on 300-mesh uncoated nickel grids for immunogold labeling.

Intracellular calcium measurement

Cytosolic free Ca2+ measurement was performed as described before (4). Briefly, the cells were loaded with 5 μm fluo-4-AM (Invitrogen) for 30 min. Fluo-4 fluorescence signals were measured using excitation and emission band-pass filters centered on 488 and 505 nm, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS 17.0 for Windows; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). In all histograms, error bars represent the sem. Statistical comparisons were made by Student's t tests between two groups. One-way ANOVA and Turkey's post hoc tests were used to evaluate statistical significance of the difference between more than two groups. A χ2 test was used to compare IVF outcome (fertilization rate and good quality embryo). Statistical significance was set as P < 0.05.

Results

Low expression levels of S100A11 in the human endometrium at the midsecretory phase are associated with a poor pregnancy outcome

Immunohistochemical analysis demonstrated that S100A11 was expressed and localized in both stroma and epithelium of human midsecretory endometrium (Fig. 1, Ab and Ac). No staining was detected in the samples in negative or isotype controls (Fig. 1, Aa and Ad). We collected the endometrial samples from 38 infertile women by biopsy examination before the cycle of IVF-ET. Demographic and clinical data regarding subsequent IVF-ET of these women are shown in Table 2. Samples were divided into two groups, successful and failed pregnancy, according to the following clinical pregnancy outcome of the patients. Clinical pregnancy was defined as the presence of a gestational sac with the heart beat visualized by ultrasound 4–6 wk after embryo transfer. We found that the expression levels of endometrial S100A11 proteins in the failed pregnancy group (n = 15) were significantly lower than that in the successful pregnancy group (n = 23) (Fig. 1, B and C).

Table 2.

Demographic data and clinic characteristics

| Items | Successful subgroup (n = 15) | Failed subgroup (n = 23) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 29.67 ± 1.10 | 28.91 ± 0.91 | NS |

| Number of oocytes | 12.20 ± 1.71 | 11.87 ± 1.19 | NS |

| Fertilization rate (%) | 88.67 % | 82.83 % | NS |

| Good-quality embryo (%) | 78.73 % | 78.45 % | NS |

| Number of transfer | 2.07 ± 0.15 | 1.78 ± 0.11 | NS |

| E2 (pmol/liter) | 10560 ± 1824 | 12100 ± 1288 | NS |

| P4 (nmol/liter) | 2.76 ± 0.46 | 2.53 ± 0.27 | NS |

| Thickness of endometrium (mm) | 11.37 ± 0.26 | 11.61 ± 0.67 | NS |

NS, Not significant.

Knockdown of S100A11 attenuates embryo implantation in mouse and JAr spheroid attachment in JAr-endometrial cell model

To verify that endometrial S100A11 mediates the process of embryo implantation, we injected specific S100A11 siRNA into the one side of uterine cavity of the pregnancy mice on d 4.5 p.c. and found that the expression levels of S100A11 proteins were significantly reduced in the endometrium treated with specific S100A11 siRNA for 48 h (Fig. 1, D and E). Meanwhile, the implantation sites were significantly decreased in the side of uteri that was injected with S100A11 siRNA, compared with another side of the uteri injected with scrambled siRNA (Fig. 1, F and G).

In the JAr spheroid-endometrial cell attachment model, we found that treatment of Ishikawa cells with S100A11 siRNA for 24 or 48 h significantly reduced the expression levels of S100A11 mRNA by 98.3 and 96.2%, respectively (Fig. 2A) and reduced S100A11 protein levels by 50.3 and 86.3%, respectively (Fig. 2, B and C). The JAr spheroid attachment (Fig. 2, D and E) rate was significantly attenuated in the cells transfected with S100A11 siRNA for 48 h (57.2%), compared with cells transfected with scrambled siRNA (86.7%, Fig. 2E).

Inhibition of S100A11 expression in human endometrial cells alters the expression levels of factors related to endometrial receptivity and immune tolerance

After transfection with S100A11 siRNA for 48 h, the mRNA level of genes related to human endometrial receptivity, including LIF, integrin-β3, EGFR, Dickkopf-1, claudin-4, and olfactomedin, were significantly altered (Fig. 2F). To determine the mediation of S100A11 in the maternal-fetal immunotolerance, we examined the expression of some T-helper type 1 (Th1) and T-helper type 2 (Th2) cytokines in human endometrial cells treated with or without specific S100A11 siRNA. Compared with the scrambled siRNA group, the mRNA expression levels of IL-4 and IL-15, which are Th2 cytokines, in S100A11 siRNA group significantly decreased, and the mRNA expression levels of IL-12α, IL-16, which are Th1 cytokines, significantly increased (Fig. 2G). Consistent with the results of mRNA analysis, the levels of selected proteins including EGFR, LIF, and IL-15 were significantly lower in S100A11 knockdown endometrial cells than that in the control (Fig. 2, H and I).

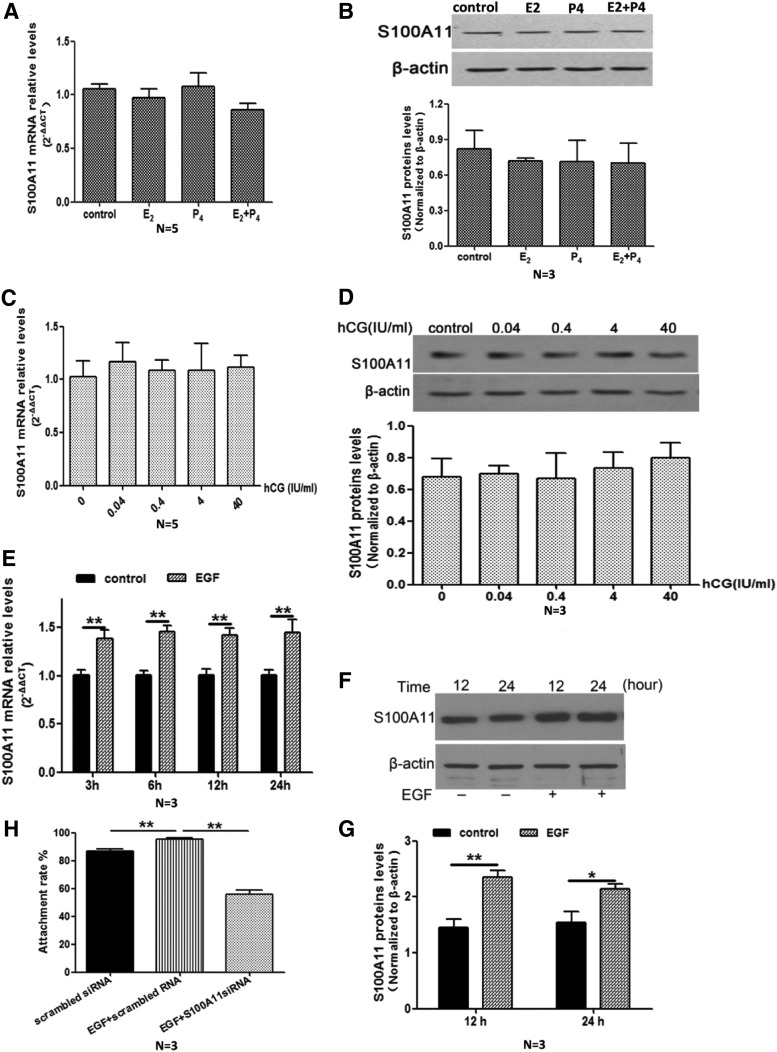

EGF, not E2 and/or P4, hCG promotes S100A11 expression in human endometrial cells

To examine whether the expression of endometrial S100A11 was regulated by hormones related to embryo implantation, we treated Ishikawa cells with E2, P4, E2 plus P4, hCG, and EGF, respectively. We found that E2, P4, E2 plus P4, or hCG treatment for 48 h did not induce significant alteration of S100A11 mRNA and protein expression (Fig. 3, A–D). However, treatment of Ishikawa cells with EGF at 20 ng/ml for 3–24 h (qRT-PCR analysis, Fig. 3E) or 12–24 h (Western blot analysis, Fig. 3, F and G) significantly increased S100A11 mRNA and protein levels in a time-dependent manner. To verify the effects of EGF on embryo implantation, we observed the JAr spheroid attachment rate on Ishikawa cells pretreated with EGF at 20 ng/ml for 24 h and found that EGF significantly increased JAr spheroid attachment rate from 86.7% in control group to 95.3% in EGF group (Fig. 3H). The enhanced JAr spheroid attachment rate by EGF was significantly attenuated (55.9%) by pretreatment of Ishikawa cells with specific S100A11 siRNA for 24 h (Fig. 3H).

Fig. 3.

Effects of different hormones and EGF on S100A11 mRNA expression levels in human endometrial cells. The expression levels of S100A11 mRNA (A) and protein (B and C) in Ishikawa cells treated with E2 (7.14 nm/liter), P4 (63.5 nm/liter), and E2 plus P4 for 24 h, respectively. S100A11 mRNA (C) and protein (D) levels in human endometrial cells treated with hCG at concentrations of 0.04–40 IU/ml for 24 h. E, S100A11 mRNA levels in human endometrial cells treated with EGF (20 ng/ml) for 3–24 h, respectively. F and G, S100A11 protein levels in human endometrial cells treated with EGF (20 ng/ml) for 12–24 h. H, Effects of EGF on JAr spheroid attachment rate in human endometrial cells treated with or without specific siRNA targeting S100A11. Data are presented as mean ± se. * or **, P < 0.05 or P < 0.01, compared with the corresponding controls. N, Number of repeated experiments.

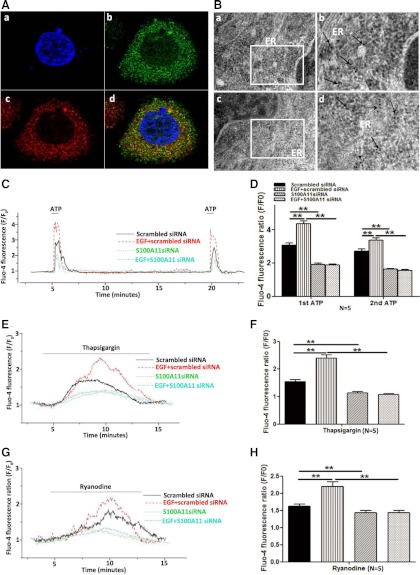

S100A11 proteins are mainly localized in endoplasmic reticulum

To assess the subcellular distribution of S100A11, Ishikawa cells were incubated with S100A11 antibody followed by Alex Fluor488 goat antimouse IgG (green), and PDIA3 antibody followed by Fluor 570 goat antirabbit IgG (red). PDIA3 is usually localized in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) lumen and the earlier study demonstrated its induction during ER stress (24). It has been shown that PDIA3 interacts with lectin chaperones, calreticulin, and calnexin to modulate folding of newly synthesized glycoproteins (25). PDIA3 is also part of the major histocompatibility complex class I peptide-loading complex, and low levels of PDIA3 failed to elicit immune responses, implicating its role in affecting immunological tolerance in cells (26, 27). In the present study, the confocal images show that S100A11 was highly colocalized with PDIA3 (Fig. 4A), suggesting that S100A11 was mainly localized in the ER. The assay with immune electronic microscopy confirmed the presence of S100A11 in the ER, which was interconnected network of tubules, vesicles, and cisternae within cells (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Subcellular distribution of S100A11 and effects of S100A11 on cytosolic Ca2+ homeostasis in human endometrial cells. A, Double staining with a rabbit antibody to S100A11 (Ab) and a mouse antibody to PDIA3 (Ac) in human endometrial cells. Aa, Nuclear staining (blue); Ad, merge of images. B, Subcellular localization of S100A11 in human endometrial cells (a and c). Bb and Bd, The region of higher magnification of Ba and Bc, respectively. Arrows indicate S100A11. Scale bars, 0.1 nm at ×65,000. C and D, Cytosolic free Ca2+ measurement in endometrial cells treated with scrambled siRNA alone, EGF plus scrambled siRNA, and specific siRNA targeting S100A11 alone and EGF plus specific siRNA targeting S100A11 for 24 h, respectively. Fluorescence was recorded from single Ishikawa cells loaded with 5 μm fluo-4-AM dye. Exposure of human endometrial cells to 10 μm ATP induced a Ca2+ transient (C). Effects of S100A11 on thapsigargin-induced Ca2+ depletion (E and F) and ryanodine-induced Ca2+ release (G and H) in human endometrial cells treated with scrambled siRNA, EGF plus scrambled siRNA, specific siRNA targeting S100A11 and EGF plus specific siRNA targeting S100A11 for 24 h, respectively, are shown. In F/F0, F is fluorescence intensity at each recording point, and F0 is fluorescence intensity at the beginning point. Data are presented as mean ± se. **, P < 0.01 compared with the corresponding controls. N, Number of repeated experiments.

S100A11 mediates EGF-enhanced calcium uptake, storage, and release from calcium stores

It has been known that EGF induces tyrosine phosphorylation and activation of phospholipase C-γ, which results in the release of Ca2+ via the activation of inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate-mediated Ca2+ stores (28). We observed that EGF promoted the elevation of cytosolic Ca2+ in endometrial cells evoked by 10 μm ATP, an agonist of purinoceptor. Treatment of Ishikawa cells with specific S100A11 siRNA not only reduced ATP-induced cytosolic Ca2+ transients but also attenuated EGF-promoted cytosolic Ca2+ transients as well (Fig. 4, C and D).

The effectiveness of thapsigargin or ryanodine to empty the microsomal Ca2+ pool (29, 30) was used to explore the effects of S100A11 on cytosolic Ca2+ homeostasis in Ishikawa cells pretreated with or without EGF. The results demonstrated that EGF enhanced the thapsigargin- or ryanodine-induced Ca2+ depletion from intracellular Ca2+ stores (Fig. 4, E–H), suggesting that more Ca2+ ions were taken up and released by Ca2+ stores in the presence of EGF. However, the EGF-enhanced Ca2+ release was significantly inhibited in Ishikawa cells transfected with S100A11 siRNA (Fig. 4, E and F).

Discussion

Our previous study demonstrated that the expression of S100A11 in the placental villous tissue of early pregnancy loss patients was significantly down-regulated (13). In this study, we found that S100A11 was expressed in human endometrium, and the low expression levels were associated with a poor pregnancy outcome. The deficient S100A11 expression in mouse endometrium and cultured human endometrial cells also resulted in a lower embryo implantation rate and a low JAr spheroid attachment rate, respectively. These data provide, for the first time, evidence that S100A11 may play a crucial role in embryo implantation and pregnancy maintenance.

To explore the well-orchestrated sequence of events and factors in embryo implantation mediated by S100A11, we examined the expression of LIF, integrin-β3, Dickkopf-1, and claudin-4, EGFR that are known as window of implantation factors and play important roles in implantation and in pregnancy establishment (31–34). Treatment of Ishikawa cells with S100A11 siRNA significantly altered the expression levels of these molecular markers. These results suggest S100A11 in endometrial cells could affect endometrial receptivity via altering the expression levels of endometrial receptive factors.

It has been shown that successful pregnancy may depend on a Th2 cytokine response, whereas a poor pregnancy outcome may be associated with an increase in Th1 cytokines (35, 36). In this study, we found that, in S100A11 knockdown endometrial cells, the Th2 cytokines including IL-4 and IL-15 significantly decreased, and the Th1 cytokines including IL-12α and IL-16 significantly increased. These data indicate that S100A11 is important in maintaining the balance of the Th1/Th2 state in endometrium.

EGF and EGFR have been found to be expressed in human endometrium (37, 38). In rats, higher levels of EGF and EGFR were present at the time of implantation after which their expression decreases gradually (18). Exogenous EGF significantly increased the blastocyte implantation rate in rats (20). Knockout of the EGFR gene in mice led to preimplantation death of the embryos (39). S100A11 could bind to the receptor for advanced glycation end products and induce expression of EGF family genes via the Akt signaling pathway in normal human keratinocytes, a model cell system of human epithelial cells. On the other hand, EGF family protein could also induce the expression and secretion of S100A11 in normal human keratinocytes (40). Here we demonstrated that EGF induced the expression of S100A11 in human endometrial cells and promoted JAr spheroid attachment rate. The increased JAr attachment rate by EGF was significantly attenuated after the treatment of endometrial cells with S100A11 siRNA, suggesting that S100A11 mediated EGF-promoted embryo implantation.

The cellular localization of S100A11 differs, depending on cell types and conditions (9). In general, S100A11 is localized in the cytoplasm, particularly in the peripheral region, in which there are abundant cytoskeleton protein, including microtubules, vimentin-intermediated filaments, and actin filaments (41). Subcellular localization of S100A11 in the endometrial cells was demonstrated in the space of ER, which is the location of intracellular Ca2+ store, suggesting involvement of S100A11 in the regulation of intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis. This suggestion was confirmed by the observation that treatment of human endometrial cells with specific siRNA targeting S100A11 reduced EGF-promoted Ca2+ transients induced by ATP in human endometrial cells. Inositol trisphosphate receptor, sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase, and ryanodine receptor are Ca2+ transporters in the Ca2+ store of ER (24–26). These transporters contribute to the Ca2+ release, uptake, and store, respectively. Thapsigargin, a selective inhibitor of the sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase, inhibits the uptake of Ca2+ into the ER, leading to the depletion of ER Ca2+ content (25). Ryanodine in nanomolar levels can cause the release of calcium from the ER (26). Treatment of endometrial cells with EGF enhances the thapsigargin-induced Ca2+ depletion and ryanodine-induced Ca2+ release, suggesting that EGF could promote Ca2+ uptake and release from Ca2+ stores. However, knockdown of S100A11 in endometrial cells significantly attenuated the thapsigargin-induced Ca2+ depletion and ryanodine-induced Ca2+ release in the presence or absence of EGF. Increase in cytosolic Ca2+ is important for embryo implantation (3, 4). These data indicate that S100A11 mediates the regulation of cytosolic Ca2+ homeostasis via promoting Ca2+ uptake and release from Ca2+ stores.

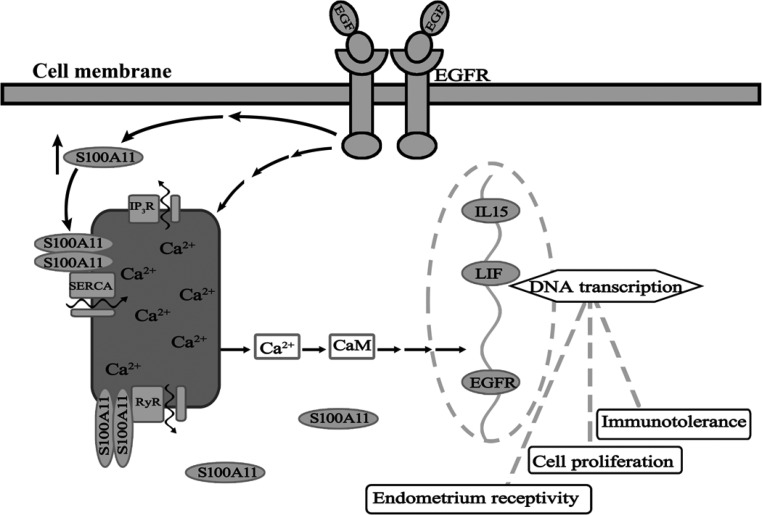

Because correct cross talk between the embryo and uterus is the key to successful implantation, it is important to find ways to pinpoint the window of implantation, ensure that the best embryo is selected, and synchronize the embryo transfer with the time of optimal endometrial receptivity. Our study provides previous undocumented insights that endometrial S100A11 would be a crossroad in the EGF-induced interaction of the embryo and uterus during the process of embryo implantation, and the down-regulation of S100A11 may cause reproductive failure. A schematic diagram depicting the potential interactions between these cellular processes is shown in Fig. 5. And most significantly, these observations suggest that endometrial S100A11 may be a potent candidate for predicting the outcome of embryo implantation in the clinic.

Fig. 5.

The schematic diagram depicting the potential interactions between EGF, S100A11, and Ca2+ signaling pathway in human endometrial cell. EGF, acting through their receptor, up-regulates S100A11, which exerts its roles in calcium uptake and release from calcium store in ER. This cross talk influences some of the calcium-trigged signaling pathways to promote the expression of genes including EGFR, IL-15, and LIF, etc., and further affect immunotolerance, cell proliferation, and endometrial receptivity to implantation, ensuring the successful execution of the implantation process. CaM, Calmodulin; IP3R, inositol trisphosphate receptor; RyR, ryanodine receptor; SERCA, sarco/endoplamic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Martin Quinn, from the University of Bristol (Bristol, UK) for reading and editing this manuscript. Author contributions included the following: X.-M.L., Y.J., and H.-J.P. designed and carried out the experimental work on the signaling pathway. G.-L.D. and Y.J. carried out the animal experiments. T.-T.W. and X.-M.L. were responsible for cell culture and qRT-PCR. Sample collection was performed by D.Z. and J.S. R.-J.Z. undertook the immunohistochemistry. X.-M.L., Y.J., and T.-T.W. contributed to RT-PCR and Western blot. H.-F.H. and J.-Z.S. designed and supervised the study. X.-M.L., G.-L.D., J.S., D.Z., H.-F.H., and J.-Z.S. wrote the manuscript, which all authors have approved.

This work was supported by the National Key Technology R&D Program of China (Grant 2012BAI32B00), the National Basic Research Program of China (Grants 2012CB944901 and 2011CB944502), and Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant LY12H04008).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have no conflicts to declare in relation to the material reported in this manuscript.

Footnotes

- Ca2+

- Calcium ions

- E2

- 17β-estradiol

- EGF

- epidermal growth factor

- EGFR

- EGF receptor

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- ET

- embryo transfer

- hCG

- human chorionic gonadotropin

- IVF

- in vitro fertilization

- LIF

- leukemia inhibitory factor

- P4

- progesterone

- p.c.

- postcoitus

- PDIA3

- antiprotein disulfide isomerase A3

- qRT-PCR

- quantitative real time-PCR

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA

- Th1

- T-helper type 1

- Th2

- T-helper type 2.

References

- 1. Clapham DE. 2007. Calcium signaling. Cell 131:1047–1058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Whitaker M. 2006. Calcium at fertilization and in early development. Physiol Rev 86:25–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tinel H, Denker HW, Thie M. 2000. Calcium influx in human uterine epithelial RL95-2 cells triggers adhesiveness for trophoblast-like cells. Model studies on signalling events during embryo implantation. Mol Hum Reprod 6:1119–1130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhang RJ, Zou LB, Zhang D, Tan YJ, Wang TT, Liu AX, Qu F, Meng Y, Ding GL, Lu YC, Lv PP, Sheng JZ, Huang HF. 2012. Functional expression of large-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels in human endometrium: a novel mechanism involved in endometrial receptivity and embryo implantation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97:543–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhang M, Tanaka T, Ikura M. 1995. Calcium-induced conformational transition revealed by the solution structure of apo calmodulin. Nat Struct Biol 2:758–767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Perocchi F, Gohil VM, Girgis HS, Bao XR, McCombs JE, Palmer AE, Mootha VK. 2010. MICU1 encodes a mitochondrial EF hand protein required for Ca(2+) uptake. Nature 467:291–296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Heizmann CW, Fritz G, Schäfer BW. 2002. S100 proteins: structure, functions and pathology. Front Biosci 7:d1356–d1368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Santamaria-Kisiel L, Shaw GS. 2011. Identification of regions responsible for the open conformation of S100A10 using chimaeric S100A11–S100A10 proteins. Biochem J 434:37–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Inada H, Naka M, Tanaka T, Davey GE, Heizmann CW. 1999. Human S100A11 exhibits differential steady-state RNA levels in various tissues and a distinct subcellular localization. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 263:135–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cross SS, Hamdy FC, Deloulme JC, Rehman I. 2005. Expression of S100 proteins in normal human tissues and common cancers using tissue microarrays: S100A6, S100A8, S100A9 and S100A11 are all overexpressed in common cancers. Histopathology 46:256–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Réty S, Osterloh D, Arié JP, Tabaries S, Seeman J, Russo-Marie F, Gerke V, Lewit-Bentley A. 2000. Structural basis of the Ca(2+)-dependent association between S100C (S100A11) and its target, the N-terminal part of annexin I. Structure 8:175–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rintala-Dempsey AC, Santamaria-Kisiel L, Liao Y, Lajoie G, Shaw GS. 2006. Insights into S100 target specificity examined by a new interaction between S100A11 and annexin A2. Biochemistry 45:14695–14705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liu AX, Jin F, Zhang WW, Zhou TH, Zhou CY, Yao WM, Qian YL, Huang HF. 2006. Proteomic analysis on the alteration of protein expression in the placental villous tissue of early pregnancy loss. Biol Reprod 75:414–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Carson DD, Bagchi I, Dey SK, Enders AC, Fazleabas AT, Lessey BA, Yoshinaga K. 2000. Embryo implantation. Dev Biol 223:217–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Singh M, Chaudhry P, Asselin E. 2011. Bridging endometrial receptivity and implantation: network of hormones, cytokines, and growth factors. J Endocrinol 210:5–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Strowitzki T, Germeyer A, Popovici R, von Wolff M. 2006. The human endometrium as a fertility-determining factor. Hum Reprod Update 12:617–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Guzeloglu-Kayisli O, Kayisli UA, Taylor HS. 2009. The role of growth factors and cytokines during implantation: endocrine and paracrine interactions. Semin Reprod Med 27:62–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Byun HS, Lee GS, Lee BM, Hyun SH, Choi KC, Jeung EB. 2008. Implantation-related expression of epidermal growth factor family molecules and their regulation by progesterone in the pregnant rat. Reprod Sci 15:678–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wollenhaupt K, Welter H, Einspanier R, Manabe N, Brüssow KP. 2004. Expression of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGF-R), vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGF-R) and fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGF-R) systems in porcine oviduct and endometrium during the time of implantation. J Reprod Dev 50:269–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Aflalo ED, Sod-Moriah UA, Potashnik G, Har-Vardi I. 2007. EGF increases expression and activity of PAs in preimplantation rat embryos and their implantation rate. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 5:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kim YJ, Lee GS, Hyun SH, Ka HH, Choi KC, Lee CK, Jeung EB. 2009. Uterine expression of epidermal growth factor family during the course of pregnancy in pigs. Reprod Domest Anim 44:797–804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tajeddine N, Gailly P. 2012. TRPC1 channel is a major regulator of EGFR signaling. J Biol Chem 287:16146–16157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. He H, Li J, Weng S, Li M, Yu Y. 2009. S100A11: diverse function and pathology corresponding to different target proteins. Cell Biochem Biophys 55:117–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mazzarella RA, Marcus N, Haugejorden SM, Balcarek JM, Baldassare JJ, Roy B, Li LJ, Lee AS, Green M. 1994. Erp61 is GRP58, a stress-inducible luminal endoplasmic reticulum protein, but is devoid of phosphatidylinositide-specific phospholipase C activity. Arch Biochem Biophys 308:454–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Coe H, Michalak M. 2010. ERp57, a multifunctional endoplasmic reticulum resident oxidoreductase. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 42:796–799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Garbi N, Tanaka S, Momburg F, Hämmerling GJ. 2006. Impaired assembly of the major histocompatibility complex class I peptide-loading complex in mice deficient in the oxidoreductase ERp57. Nat Immunol 7:93–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Panaretakis T, Joza N, Modjtahedi N, Tesniere A, Vitale I, Durchschlag M, Fimia GM, Kepp O, Piacentini M, Froehlich KU, van Endert P, Zitvogel L, Madeo F, Kroemer G. 2008. The co-translocation of ERp57 and calreticulin determines the immunogenicity of cell death. Cell Death Differ 15:1499–1509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ma HT, Patterson RL, van Rossum DB, Birnbaumer L, Mikoshiba K, Gill DL. 2000. Requirement of the inositol trisphosphate receptor for activation of store-operated Ca2+ channels. Science 287:1647–1651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Thastrup O, Cullen PJ, Drobak BK, Hanley MR, Dawson AP. 1990. Thapsigargin, a tumor promoter, discharges intracellular Ca2+ stores by specific inhibition of the endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87:2466–2470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Marx SO, Reiken S, Hisamatsu Y, Jayaraman T, Burkhoff D, Rosemblit N, Marks AR. 2000. PKA phosphorylation dissociates FKBP12.6 from the calcium release channel (Ryanodine receptor): defective regulation in failing hearts. Cell 101:365–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Castelbaum AJ, Ying L, Somkuti SG, Sun J, Ilesanmi AO, Lessey BA. 1997. Characterization of integrin expression in a well differentiated endometrial adenocarcinoma cell line (Ishikawa). J Clin Endocrinol Metab 82:136–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kodithuwakku SP, Ng PY, Liu Y, Ng EH, Yeung WS, Ho PC, Lee KF. 2011. Hormonal regulation of endometrial olfactomedin expression and its suppressive effect on spheroid attachment onto endometrial epithelial cells. Hum Reprod 26:167–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kao LC, Tulac S, Lobo S, Imani B, Yang JP, Germeyer A, Osteen K, Taylor RN, Lessey BA, Giudice LC. 2002. Global gene profiling in human endometrium during the window of implantation. Endocrinology 143:2119–2138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Stewart CL, Kaspar P, Brunet LJ, Bhatt H, Gadi I, Köntgen F, Abbondanzo SJ. 1992. Blastocyst implantation depends on maternal expression of leukaemia inhibitory factor. Nature 359:76–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kwak-Kim JY, Chung-Bang HS, Ng SC, Ntrivalas EI, Mangubat CP, Beaman KD, Beer AE, Gilman-Sachs A. 2003. Increased T helper 1 cytokine responses by circulating T cells are present in women with recurrent pregnancy losses and in infertile women with multiple implantation failures after IVF. Hum Reprod 18:767–773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Piccinni MP, Scaletti C, Maggi E, Romagnani S. 2000. Role of hormone-controlled Th1- and Th2-type cytokines in successful pregnancy. J Neuroimmunol 109:30–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hofmann GE, Scott RT, Jr, Bergh PA, Deligdisch L. 1991. Immunohistochemical localization of epidermal growth factor in human endometrium, decidua, and placenta. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 73:882–887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pfeiffer D, Spranger J, Al-Deiri M, Kimmig R, Fisseler-Eckhoff A, Scheidel P, Schatz H, Jensen A, Pfeiffer A. 1997. mRNA expression of ligands of the epidermal-growth-factor-receptor in the uterus. Int J Cancer 72:581–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Threadgill DW, Dlugosz AA, Hansen LA, Tennenbaum T, Lichti U, Yee D, LaMantia C, Mourton T, Herrup K, Harris RC, et al. 1995. Targeted disruption of mouse EGF receptor: effect of genetic background on mutant phenotype. Science 269:230–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sakaguchi M, Sonegawa H, Murata H, Kitazoe M, Futami J, Kataoka K, Yamada H, Huh NH. 2008. S100A11, a dual mediator for growth regulation of human keratinocytes. Mol Biol Cell 19:78–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bianchi R, Giambanco I, Arcuri C, Donato R. 2003. Subcellular localization of S100A11 (S100C) in LLC-PK1 renal cells: calcium- and protein kinase C-dependent association of S100A11 with S100B and vimentin intermediate filaments. Microsc Res Tech 60:639–651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]