Abstract

Methotrexate (MTX) is a folate-antagonist used in several neoplastic and inflammatory diseases. Reports of pulmonary complications in patients given low-dose MTX therapy are increasing. Pulmonary toxicity from MTX has a variable frequency and can present with different forms. Most often MTX-induced pneumonia in patients affected by rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is reported.

In this paper we describe a case of MTX-related pneumonitis in a relatively young woman affected by Crohn's disease who presented non-productive cough, fever and dyspnea on exercise. Chest X-ray demonstrated bilateral interstitial infiltrates and at computed tomography (CT) ground-glass opacities appeared in both lungs. At spirometry an obstructive defect was demonstrated. A rapid improvement of symptoms and the regression of radiographic and spirometric alterations was achieved through MTX withdrawal and the introduction of corticosteroid therapy.

Keywords: Crohn's disease, CT, methotrexate, pneumonitis, spirometry

Introduction

The rate of extra-intestinal manifestations in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) ranges from 21 to 41% [1,2], increasing with the duration of intestinal disease. The true prevalence of lung involvement in IBD seems rather variable; in fact Edwards et al. [3] in their review of 624 cases found no case of pulmonary complication, whereas Rogers et al. [4] report an incidence of 0.4%.

Respiratory diseases occurring in IBD vary from subclinical abnormality of pulmonary function to disease of large and small airways and parenchymal involvement. As to the latter, the side effects of treatment in the form of hypersensitivity reactions must be taken into account [5].

MTX, an antagonist of folic acid, is the most commonly used drug in rheumatoid arthritis and since the end of 1980 it is also administered for its anti-inflammatory activity in refractory IBD disease, with the aim to improve symptoms and reduce requirements for prednisone [6,7]. This drug is responsible for numerous adverse reactions involving multiple organs, some of which life-threatening like MTX-induced pneumonitis (MIP), which generally appears within the first year of treatment [8,9] though a delay of 1-4 weeks after discontinuation of the drug is also reported [10-12]. It may present as acute, subacute or chronic [13]. The prevalence of pneumonitis is reported to be 0.3-0.7% [14]. Imokawa et al. [15], in their review of the English literature, show 123 cases of MIP, but none was affected by IBD. To our knowledge, only one case of MTX-related pneumonitis in a patient with Crohn's disease has formerly been reported [16].

Here we report a second case of pneumonitis MTX-induced in Crohn's disease.

Case report

A 44-year old woman was followed up by the Gastroenterology Unit of our hospital since 1995 when Crohn's disease was diagnosed. She underwent steroid treatment (more than two cycles/year of prednisone 20 mg/day) without complete disease remission. In 1998 she was admitted to hospital for a moderate/severe relapse of IBD with appearance of extraintestinal manifestations (peripheral arthritis, sacroileitis and erythema nodosum). Thus, azathioprine (2.5 mg/kg/die) was added to a higher dose of prednisone (1 mg/Kg/die) with rapid resolution of symptoms, but this drug was discontinued after few months owing to the onset of acute pancreatitis. At that moment a maintenance treatment with methotrexate was refused by the patient due to a possible pregnancy, so a long-term strategy of steroid tapering was applied (that ended in November 1999). Between 1999 and 2001 some light relapses were treated with salazopirine and antibiotic therapy.

In 2003, because of a new relapse, an induction regimen with anti tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alfa antibodies (infliximab 5 mg/kg at 0, 2 and 6 weeks) was started, obtaining a complete clinical and endoscopic remission.

A maintenance therapy with oral methotrexate 15 mg once a week was started in April 2003, with clinical and endoscopic remission until July 2005, when, due to the onset of acute dyspnea, cough without sputum production, fever and parossistic supraventricular tachycardia, the patient was admitted to the emergency ward of our general hospital. At presentation the patient was tachypneic (22 breaths/min), tachycardic (140 bpm) and febrile (38.5°C) and reported dyspnea during exercise for at least two weeks. She did not smoke or suffer from any pulmonary disease in the past. At physical examination no cyanosis or other alterations were evident, while at auscultation of the thorax bilateral dry crackles in medium-low lung fields were found. Laboratory studies showed an increase in inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein 2.8 mg/dl, normal value < 0.5 mg/dl; erythrocyte sedimentation rate 56 mm/h) and in white blood cells count (14,200 with 68% neutrophils and 6% eosinophils), and a mild anemia was detected (hemoglobin 11.2 g/dl). Arterial blood gas analysis showed normoxemia with respiratory alkalosis due to hyperventilation: pH 7.47, PaCO2 29.3 mm Hg, PaO2 103.6 mm Hg, BE -1.1 mmol/l).

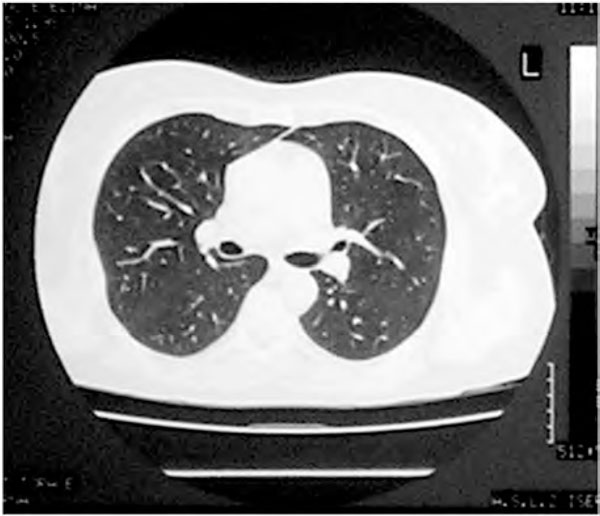

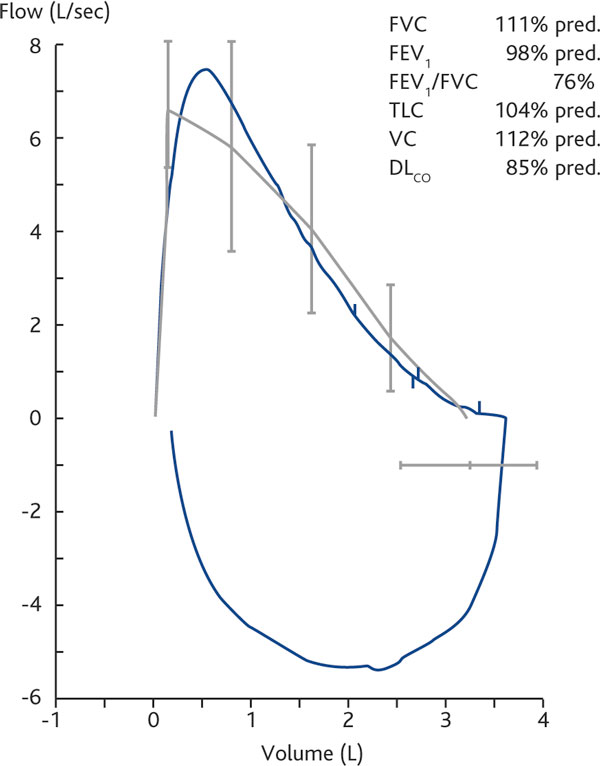

The chest radiograph showed diffuse bilateral reticular infiltrates of the mid-lower zones of both lungs with merging at the left base. A high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) of the thorax showed a bilateral distribution of ground glass opacities especially diffuse in the mid-upper zones of the lung, sparing the peripheral fields, and without distortion of pulmonary parenchyma (Figure 1a). Pulmonary function tests (PFTs) revealed an obstructive mild defect, with severe reduction of the diffusing lung capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) (Figure 1b). The serological tests for the detection of common respiratory viruses, Legionella pneumo phila, Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Rickettsia, together with the autoantibodies assays (ANA, ENA, ANCA), were negative (Table 1). Bacterial and fungal stains and culture of sputum were negative. On the basis of clinical setting and radiological pattern an acute interstitial lung disease caused by methotrexate was suspected. Methotrexate was discontinued and corticosteroids (prednisone 1 mg/kg) plus antibiotic therapy (clarythromycin 1 gr/die) were prescribed and the patient's illness resolved within 1 week of starting this therapy.

Figure 1a.

HRCT of lung during methotrexate therapy. Diffuse bilateral alveolar infiltrates and ground glass areas can be seen without distortion of pulmonary parenchyma. Definition of abbreviation: HRCT, high-resolution computed tomography.

Figure 1b.

PFT at admission to hospital. Mild obstructive defect with severe reduction of DLCO. Definition of abbreviations: DLCO, diffusing lung capacity for carbon monoxide; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC, forced vital capacity; PFT, pulmonary function test; TLC, total lung capacity; VC, vital capacity.

Table 1.

Serological tests

| Serodiagnosis for Listeria | ||

|---|---|---|

| Anti-Listeria H I serotype | Negative | Negative < 160 |

| Anti-Listeria H 4b serotype | Negative | Negative < 160 |

| Anti-Listeria O I serotype | Negative | Negative < 160 |

| Anti-Listeria O 4b serotype | Negative | Negative < 160 |

| Serodiagnosis for most common pneumotropic pathogens | ||

| Legionella pneumophila IgM | Absent | |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae IgM | Absent | |

| Coxiella burnetii IgM | Absent | |

| Chlamydia pneumoniae IgM | Absent | |

| Adenovirus IgM | Absent | |

| Respiratory syncytial virus IgM | Absent | |

| Influenza A virus IgM | Absent | |

| Influenza B virus IgM | Absent | |

| Parainfluenza 1, 2, 3 virus IgM | Absent | |

| Cytomegalovirus Ab | ||

| Cytomegalovirus IgG | 599 UA/ml | Negative < 15 |

| Cytomegalovirus IgM | 0.327 UA/ml | Negative < 0.500 |

Four weeks later the HRCT showed no abnormalities of the lung parenchyma (Figure 2a) and the PFTs were normal (Figure 2b). After this episode there was no further occurrence of respiratory symptoms. At present, the patient is on stable remission with biological treatment (adalimumab) without adverse effects.

Figure 2a.

HRCT of lung after discontinuation of methotrexate therapy. No lung abnormalities can be observed. Definition of abbreviation: HRCT, high-resolution computed tomography.

Figure 2b.

PFT at outcome. Normalization of functional parameters. Definition of abbreviations: DLCO, diffusing lung capacity for carbon monoxide; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC, forced vital capacity; PFT, pulmonary function test; TLC, total lung capacity; VC, vital capacity.

Discussion

Among extraintestinal manifestations (EIM) of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) pulmonary involvement has been described much less frequently than other complications [1,2], ranging from subclinical pulmonary function abnormalities to interstitial fibrosis. However, Songur et al. [17] reported that HRCT or pulmonary function abnormalities are present in a surprisingly large proportion of IBD patients (53% and 58%, respectively) and 42% of the patients with HRCT abnormalities did not have respiratory symptoms. Some authors reported pulmonary impairment in IBD patients to be related to disease activity [18-20]: approximately 80% of the patients with pulmonary involvement had active bowel disease [17], suggesting a direct pathogenetic link to the IBD itself; however an ongoing bowel inflammation is not a prerequisite for the onset of respiratory alterations, since bronchopulmonary diseases that developed after colectomy have been reported [21]. In all cases, drug-induced pulmonary disease, a rare side effect of sulfalazina, mesalamine and methotrexate, must be ruled out [22].

Methotrexate, which has recently been shown to have utility for long-term maintenance therapy in Crohn's disease, has been related to a pneumonitis (methotrexate-induced pneumonitis, MIP) that can become life threatening [23] and represent a serious and far less predictable side-effect of treatment with MTX [24].

As many as 60 to 93% of patients treated with methotrexate eventually develop at least one adverse reaction, most commonly involving the skin, gastrointestinal tract, or central nervous system [25,26]. Most of these reactions are not life-threatening. Nevertheless, up to 30% of patients treated for more than five years with MTX discontinue the therapy because of unacceptable toxicity [27,28]. Major and potentially life-threatening toxicities affect lung [29,30], liver [31], and the hematopoietic system [32]. Most series estimate that pulmonary toxicity develops in 2 to 7% of patients receiving methotrexate [33,34], but some reports suggest an incidence as high as 11.6% [35]. Pulmonary toxicity has been well-described and MIP is the most common complication associated with the use of methotrexate [36-38], but a variety of other pulmonary conditions have been associated with the use of this drug, including bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia [29], acute lung injury with noncardiogenic pulmonary edema [39], pulmonary fibrosis (which may be rapidly progressive), bronchitis with airways hyperreactivity [39], and isolated pleuritis [40]. The occurrence of MIP has mainly been reported in patients affected by rheumatoid arthritis [15] and to our knowledge only one other case of pulmonary toxicity has been described in a patient affected with IBD. Thus, this is the second case of MIP occurring in the course of IBD [16].

Surprisingly, the two cases were very similar; in both cases the patients were relatively young women, both affected by Crohn's disease and with steroid-dependent disease.

There is no single pathognomonic test for methotrexate pulmonary toxicity, and a clinicopathological correlation is required for each individual case [41]. The diagnosis might be difficult and it is mainly a diagnosis of exclusion: in fact it is imperative to rule out the possibility of pulmonary infection and other respiratory diseases before diagnosing and treating methotrexate-induced lung alterations [14,42].

Four different groups have proposed similar criteria, specifically based on anamnestic data and clinical manifestations, radiographic abnormalities, bronchoalveolar lavage, and lung histology in a minority of cases, for the diagnosis of MTX lung injury [43-46] (Table 3).

The proposed multiparametric scoring systems have not been adequately validated and their sensitivity has not been studied [23]; however, the clinical setting together with some radiological findings are useful for formulating the diagnosis [14] as in the present case.

Interstitial opacities or mixed interstitial and alveolar infiltration can be demonstrated at the chest X-ray, but this can also be normal in a minority of cases [15]. HRCT is superior to plain chest radiographs for demonstrating and characterizing the MTX-induced toxicity [47], and it can show patchy areas of ground glass attenuation with small areas of consolidation [48], i.e. precisely the pattern we observed in our patient.

Pulmonary function tests in methotrexate pneumonitis generally reveal a volume decrease, especially of vital capacity (VC), and a reduction of carbon monoxide diffusing capacity (DLCO), [36,37] even if these features are suggestive of but not specific for MIP [49]. Nevertheless, the majority of patients submitted to long term methotrexate therapy show no deterioration in pulmonary function [50-52], and in few cases was worsening of airflow obstruction noted, although it is unclear to what degree methotrexate was responsible for these alterations [49,53].

Pulmonary histology can be helpful in making the differential diagnosis from other causes, but the findings are not specific or diagnostic for any MTX-induced pulmonary disease, whereas bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) is helpful to rule out an infectious etiology [54].

Evidence in support of the diagnosis of pulmonary toxicity from methotrexate results from clinical improvement after discontinuation of the drug and/or the response to corticosteroid treatment. A subacute illness is the commonest modality of presentation of methotrexate pulmonary toxicity [14,55]. The majority of patients who develop methotrexate pulmonary toxicity do so within the first year of therapy [42], but cases with an onset as early as 12 days after have been reported [15], and pulmonary complications may appear even some weeks after discontinuation of treatment [56,57] or after a longer period of drug administration. In fact, in the case presented here the respiratory symptoms began late with insidious dyspnea during exercise and progressed until an acute increase in symptoms with fever, dry cough, tachypnea and tachycardia forced the patient to seek hospital admission, while MTX therapy had been started more than two years before. We do not know the precise reason why methotrexate pulmonary toxicity did manifest such a long time after the beginning of treatment; certainly it was not related to an exacerbation of the chronic intestinal disease that was well controlled at that time.

Subacute pneumonitis manifests with dyspnea, non productive cough, fever, and crackles with tachypnea on physical examination [15]. A progression to pulmonary fibrosis is observed in approximately 10% of patients [29]. The clinical presentation of acute methotrexate pneumonitis is generally unspecific with fever, chills, cough, dyspnea, chest pain and fatigue [46,58-61] and it has been observed in 2 to 5% of patients treated for rheumatoid arthritis [38,59-61].

The prognosis of MTX pneumonitis is not entirely benign [14,36] and rapid progression to respiratory failure may also occur [36,37].

No prospective trials concerning the therapy for MTX-induced pneumonitis have been performed. Imokawa et al. [15] in their review of 123 cases of MIP (none affected by IBD) reported 26% of cases treated with discontinuation of MTX only, 53% with discontinuation associated to administration of corticosteroids and 21% treated with other non-explained therapies. Mortality was 15.8%, and in 76% of these cases due to respiratory disease. In their own case series of 9 MIP, MTX was stopped in all cases, corticosteroid therapy was started in 8, and 2 patients died because of respiratory failure. Although there is no established protocol, the therapy is generally started with 1 mg/kg per day of methylprednisolone or equivalents, initially intravenous in severely ill patients, and tapered over the subsequent 2 or 4 weeks [62].

The value of corticosteroids in methotrexate pulmonary toxicity has not been examined in large-sized trials [35] but such trials likely would be unnecessary due to the proven efficacy of cortico steroids in a life threatening disease [36]. The prognosis is substantially good, although some abnormalities of respiratory function could remain, while about a 1% mortality rate is calculated [36,63]. Empiric antimicrobial therapy directed at likely pathogens may be indicated while definitive proced ures and cultures are performed. As occurred in our patient, clinical improvement usually occurs within some days of stopping the drug, followed by improvement in the chest radiograph over several weeks [45]. While there are reports of successful rechallenge with methotrexate and even regression of pulmonary toxicity despite continued therapy, these approaches are not recommended [44,64] since they may induce a relapse of MIP or death [24].

In our specific clinical setting, the diagnosis of MTX-induced pneumonitis is based on the set of criteria proposed by Alarcón et al. [43] (Table 2), of which two major criteria and three minor criteria were encountered in our patient. In Alarcón et al.'s study [43] older age represents the strongest predictor of lung injury, the risk being double in 50-59 year-old patients and six-fold in patients over 60 years old. As regards the risk factors indicated by Alarcón et al., neither older age, nor diabetes nor hypoalbuminemia were present, and no pre-existing pulmonary diseases appeared in the anamnestic evaluation of our non smoking patient, as supposed by Searles [45]. Only a mild chronic anaemia was present to debilitate our patient.

Table 2.

Criteria for definite or probable methotrexate pneumonitis diagnosis

| Methotrexate pneumonitis is characterized as "definite" if one of the major criteria is present in conjunction with three of the five minor criteria. "Probable" methotrexate pneumonitis is present if major criteria 2 and 3 plus two of the five minor criteria are present [43]*. |

| Major criteria |

| • Hypersensitivity pneumonitis by histopathology without evidence of pathogenic organisms |

| • Radiologic evidence of pulmonary interstitial or alveolar infiltrates |

| • Blood cultures (if febrile) and initial sputum cultures (if sputum is produced) that are negative for pathogenic organisms. |

| Minor criteria |

| • Shortness of breath for less than eight weeks |

| • Nonproductive cough |

| • Oxygen saturation ≤ 90% on room air at the time of initial evaluation |

| • DLCO ≤ 70% of predicted for age |

| • Leukocyte count ≤ 15,000 cells/mm3. |

* Modified from [45].

The pathogenesis of MTX lung toxicity is uncertain. The two most suggestive theories are: an acute hypersensitivity reaction or a direct cytotoxic action [64]. The first is supported by the evidence in a few cases of eosinophilia and release of lymphokine, leucocyte inhibitor factor from peripheral blood lymphocytes [65] and a dramatic response to corticosteroids.

The second is supported by the fact that MTX accumulates preferentially in the lung [66] and a clinical resolution may follow the stop of MTX without administration of corticosteroids.

In our patient the presence of eosinophilia, and the prompt improvement in symptoms and in radio graphic alterations observed after corticosteroid therapy, make us certain of a possible immune-mediated phenomenon.

The time of MIP presentation is unpredictable; in our patient it appeared when she had been undergoing methotrexate treatment for 25 months. Hence, as MIP is a potentially fatal disease, a prompt evaluation of any new respiratory symptoms in patients treated with MTX is imperative. In fact, early diagnosis of possible alterations, even monitoring pulmonary function tests [67], may reduce severe morbidity and mortality.

Conflict of interests statement

None of the authors has any conflict of interest to declare in relation to the subject of this manuscript.

References

- Storch I, Sachar D, Katz S. Pulmonary manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2003;9:104–115. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200303000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenstein AJ, Janowitz HD, Sachar DB. The extra-intestinal complications of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis: a study of 700 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 1976;55:401–412. doi: 10.1097/00005792-197609000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards FC, Truelove SC. The course and prognosis of ulcerative colitis. III, Complications. Gut. 1964;5:1–22. doi: 10.1136/gut.5.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers BH, Clark LM, Kirsner JB. The epidemiologic and demographic characteristics of inflammatory bowel disease: an analysis of a computerized file of 1400 patients. J Chronic Dis. 1971;24:743–773. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(71)90087-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford RM. Transient pulmonary eosinophilia and asthma. A review of 20 cases occurring in 5,702 asthma sufferers. Am Rev Resp Dis. 1966;93:797–803. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1966.93.5.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feagan BG, Rochon J, Fedorak RN, Irvine EJ, Wild G, Sutherland L, Steinhart AH, Greenberg GR, Gillies R, Hopkins M, Hanauer SB, McDonald JW. for the North American Crohn's Study Group Investigators. Methotrexate for the treatment of Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:292–297. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199502023320503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozarek RA, Patterson DJ, Gelfand MD, Botoman VA, Ball TJ, Wilske KR. Methotrexate induces clinical and histologic remission in patients with refractory inflammatory bowel disease. Ann Intern Med. 1989;110:353–356. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-110-5-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grove ML, Hassell AB, Hay EM, Shadforth MF. Adverse reactions to disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs in clinical practice. QJM. 2001;94:309–319. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/94.6.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnabel A, Herlyn K, Burchardi C, Reinhold-Keller E, Gross WL. Long-term tolerability of methotrexate at doses exceeding 15 mg per week in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Int. 1996;15:195–200. doi: 10.1007/BF00290521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case records of the Massachussets General Hospital. Weekly clinicopathological excercises. Case 6-1985. Progressive pneumonitis after chemotherapy for breast carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:359–369. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198502073120608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz GF, Anderson ST. Methotrexate induced pneumonitis in a young woman with psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1990;17:980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louie S, Lillington GA. Low dose methotrexate pneumonitis in rheumatoid arthritis. Thorax. 1986;41:703–704. doi: 10.1136/thx.41.9.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridley MG, Wolfe CS, Mathews JA. Life threatening acute pneumonitis during low dose methotrexate treatment for rheumatoid arthritis: a case report and review of the literature. Ann Rheum Dis. 1988;47:784–788. doi: 10.1136/ard.47.9.784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera P, Laan RF, van Riel PL, Dekhuijzen PN, Boerbooms AM, van de Putte LB. Methotrexate-related pulmonary complications in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1994;53:434–439. doi: 10.1136/ard.53.7.434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imokawa S, Colby TV, Leslie KO, Helmers RA. Methotrexate pneumonitis: review of the literature and histopathological findings in nine patients. Eur Respir J. 2000;15:373–381. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.2000.15b25.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brechmann T, Heyer C, Schmiegel W. Methotrexateinduced pneumonitis in a woman with Crohn's disease. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2007;132:1759–1762. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-984962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Songür N, Songür Y, Tüzün M, Doğan I, Tüzün D, Ensari A, Hekimoglu B. Pulmonary function tests and high-resolution CT in the detection of pulmonary involvement in inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Gastoenterol. 2003;37:292–298. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200310000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed-Hussein AA, Mohamed NA, Ibrahim ME. Changes in pulmonary function in patients with ulcerative colitis. Respir Med. 2007;101:977–982. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munck A, Murciano D, Pariente R, Cezard JP, Navarro J. Latent pulmonary function abnormalities in children with Crohn's disease. Eur Respir J. 1995;8:377–380. doi: 10.1183/09031936.95.08030377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrlinger KR, Noftz MK, Dalhoff K, Ludwig D, Stange EF, Fellermann K. Alterations in pulmonary function in inflammatory bowel disease are frequent and persist during remission. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:377–381. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raj AA, Birring SS, Green R, Grant A, de Caestecker J, Pavord ID. Prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in patients with airways disease. Respir Med. 2008;102:780–785. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Andrea N, Vigliarolo R, Sanguinetti CM. Respiratory involvement in inflammatory bowel. Multidisciplinary Respiratory Medicine. 2010;3:173–182. doi: 10.1186/2049-6958-5-3-173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu PC, Lan JL, Hsieh TY, Jan YJ, Huang WN. Methotrexate pneumonitis in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2003;36:137–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremer JM, Alarcón GS, Weinblatt ME, Kaymakcian MV, Macaluso M, Cannon GW, Palmer WR, Sundy JS, St Clair EW, Alexander RW, Smith GJ, Axiotis CA. Clinical, laboratory, radiographic, and histopathologic features of methotrexate-associated lung injury in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a multicenter study with literature review. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1829–1837. doi: 10.1002/art.1780401016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman TA, Polisson RP. Methotrexate: adverse reactions and major toxicities. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1994;20:513–528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannwarth B, Labat L, Moride Y, Schaeverbeke T. Methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis. An update. Drugs. 1994;47:25–50. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199447010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittle SL, Hughes RA. Folate supplementation and methotrexate treatment in rheumatoid arthritis: a review. Rheumatology. 2004;43:267–271. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rau R, Schleusser B, Herborn G, Karger T. Long-term treatment of destructive rheumatoid arthritis with methotrexate. J Rheumatol. 1997;24:1881–1889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lateef O, Shakoor N, Balk RA. Methotrexate pulmonary toxicity. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2005;4:723–730. doi: 10.1517/14740338.4.4.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon GW. Methotrexate pulmonary toxicity. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1997;23:917–937. doi: 10.1016/S0889-857X(05)70366-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremer JM, Alarcón GS, Lighfoot RW Jr, Willkens RF, Furst DE, Williams HJ, Dent PB, Weinblatt ME. Methotrexate for rheumatoid arthritis. Suggested guidelines for monitoring liver toxicity. American College of Rheumatology. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37:316–328. doi: 10.1002/art.1780370304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalantzis A, Marshman Z, Falconer DT, Morgan PR, Odell EW. Oral effects of low-dose methotrexate treatment. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;100:52–62. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2004.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rau R, Herborn G. Benefit and risk of methotrexate treatment in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2004;22(5 Suppl 35):S83–S94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borchers AT, Keen CL, Cheema GS, Gershwin ME. The use of methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2004;34:465–483. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves MR, Mowat AG, Benson MK. Acute pneumonitis associated with low dose methotrexate treatment for rheumatoid arthritis: report of five cases and review of published reports. Thorax. 1992;47:628–633. doi: 10.1136/thx.47.8.628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JA Jr, White DA, Matthay RA. Drug-induced pulmonary disease: Part 1: Cytotoxic drugs. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1986;133:321–340. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1986.133.2.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch JP, McCune WJ. Immunosuppressive and cytotoxic pharmacotherapy for pulmonary disorders. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:395–420. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.2.9032171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilliquin P, Renoux M, Perrot S, Puéchal X, Menkès CJ. Occurrence of pulmonary complications during methotrexate therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol. 1996;35:441–445. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/35.5.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IIkuni N, Iwami S, Kasai S, Tokuda H. Noncardiogenic pulmonary edema in low-dose oral methotrexate therapy. Intern Med. 2004;43:846–851. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.43.846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walden PA, Mitchell-Weggs PF, Coppin C, Dent J, Bagshawe KD. Pleurisy and methotrexate treatment. Br Med J. 1977;2:867. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6091.867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colby T, Carrington C. In: Pathology of the lung. 2. Thurlbeck W, Churg A, editor. New York, Thieme Medical Publisher; 1995. Interstitial lung disease; pp. 589–737. [Google Scholar]

- LeMense GP, Sahn SA. Opportunistic infection during treatment with low dose methotrexate. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150:258–260. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.150.1.8025760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alarcón GS, Kremer JM, Macaluso M, Weinblatt ME, Cannon GW, Palmer WR, St Clair EW, Sundy JS, Alexander RW, Smith GJ, Axiotis CA. Risk factors for methotrexateinduced lung injury in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. A multicenter, case-control study. Methotrexate-Lung Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:356–364. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-5-199709010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson CW, Cannon GW, Egger MJ, Ward JR, Clegg DO. Pulmonary disease during the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with low dose pulse methotrexate. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1987;16:186–195. doi: 10.1016/0049-0172(87)90021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Searles G, McKendry RJ. Methotrexate pneumonitis in rheumatoid arthritis: potential risk factors. Four case reports and review of the literature. J Rheumatol. 1987;14:1164–1171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden MR, Katz RS, Balk RA, Golden HE. The relationship of preexisting lung disease to the development of methotrexate pneumonitis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1995;22:1043–1047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederer J, Schnabel A, Muhle C, Gross WL, Heller M, Reuter M. Correlation between HRCT findings, pulmonary function tests and bronchoalveolar lavage cytology in interstitial lung disease associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Eur Radiol. 2004;14:272–280. doi: 10.1007/s00330-003-2026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padley SP, Adler B, Hansell DM, Müller NL. High-resolution computed tomography of drug-induced lung disease. Clin Radiol. 1992;46:232–236. doi: 10.1016/S0009-9260(05)80161-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saravanan V, Kelly CA. Reducing the risk of methotrexate pneumonitis in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology. 2004;43:143–147. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keg466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeurissen M, Boerbooms A, Festen J, van de Putte L, Doesburg W. Serial pulmonary function tests during randomized, double-blind trial of azathioprine versus methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1991;34:S90. doi: 10.1002/art.1780340805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croock A, Furst D, Helmers R. et al. Methotrexate does not alter pulmonary function in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1989;32:S60. [Google Scholar]

- Velay B, Lamboley L, Massonnet B. Prospective study of respiratory function in rheumatoid arthritis treated with methotrexate. Eur Resp J. 1988;1(S2):371S. [Google Scholar]

- Beyeler C, Jordi B, Gerber NJ, Im Hof V. Pulmonary function in rheumatoid arthritis treated with low-dose methotrexate: a longitudinal study. Br J Rheumatol. 1996;35:446–452. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/35.5.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leduc D, De Vuyst P, Lheureux P, Gevenois PA, Jacobovitz D, Yernault JC. Pneumonitis complicating low-dose methotrexate therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Discrepancies between lung biopsy and bronchoalveolar lavage findings. Chest. 1993;104:1620–1623. doi: 10.1378/chest.104.5.1620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neves C, Jorge R, Barcelos A. A teia de toxicidade do methotrexato. Acta Reumatol Port. 2009;34:11–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsasser S, Dalquen P, Soler M, Perruchoud AP. Methotrexate-induced pneumonitis: appearance four weeks after discontinuation of treatment. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;140:1089–1092. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/140.4.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bandt M, Rat AC, Palazzo E, Kahn MF. Delayed methotrexate pneumonitis (letter) J Rheumatol. 1991;18:1943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St Clair EW, Rice JR, Snyderman R. Pneumonitis complicating low-dose methotrexate therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Arch Intern Med. 1985;145:2035–2038. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1985.00360110105023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassell A, Dawes P. Serious problems with methotrexate? Br J Rheumatol. 1994;33:1001–1002. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/33.11.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll GJ, Thomas R, Phatouros CC, Atchison MH, Leslie AL, Cook NJ, D'Souza I. Incidence, prevalence and possible risk factors for pneumonitis with rheumatoid arthritis receiving methotrexate. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:51–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenow EC. Drug-induced pulmonary disease. Dis Mon. 1994;40:253–310. doi: 10.1016/0011-5029(94)90025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon GW, Ward JR, Clegg DO, Samuelson CO Jr, Abbott TM. Acute lung disease associated with low-dose pulse methotrexate therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1983;26:1269–1274. doi: 10.1002/art.1780261015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Veen MJ, Dekker JJ, Dinant HJ, van Soesbergen RM, Bijlsma JW. Fatal pulmonary fibrosis complicating low dose methotrexate therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1995;22:1766–1768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sostman HD, Matthay RA, Putman CE, Smith GJ. Methotrexate-induced pneumonitis. Medicine (Baltimore) 1976;55:371–388. doi: 10.1097/00005792-197609000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akoun GM, Gauthier-Rahman S, Mayaud CM, Touboul JL, Denis MF. Leucocyte migration inhibition in methotrexate-induced pneumonitis. Evidence for an immunologic cellmediated mechanism. Chest. 1987;91:96–99. doi: 10.1378/chest.91.1.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson LL, Collins GJ, Ojima Y, Sullivan RD. A study of the distribution of methotrexate in human tissues and tumors. Cancer Res. 1970;30:1344–1348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green L, Schattner A, Berkenstadt H. Severe reversible interstitial pneumoniti induced by low dose methotrexate: report of a case and review of the literature. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:110–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]