Abstract

Adenosine receptors are major targets of caffeine, the most commonly consumed drug in the world. There is growing evidence that they could also be promising therapeutic targets in a wide range of conditions, including cerebral and cardiac ischaemic diseases, sleep disorders, immune and inflammatory disorders and cancer. After more than three decades of medicinal chemistry research, a considerable number of selective agonists and antagonists of adenosine receptors have been discovered, and some have been clinically evaluated, although none has yet received regulatory approval. However, recent advances in the understanding of the roles of the various adenosine receptor subtypes, and in the development of selective and potent ligands, as discussed in this review, have brought the goal of therapeutic application of adenosine receptor modulators considerably closer.

Extracellular adenosine acts as a local modulator with a generally cytoprotective function in the body1. Its effects on tissue protection and repair fall into four categories: increasing the ratio of oxygen supply to demand; protecting against ischaemic damage by cell conditioning; triggering anti-inflammatory responses; and the promotion of angiogenesis2.

There are four known subtypes of adenosine receptors (ARs) – referred to as A1, A2A, A2B and A3 – each of which has a unique pharmacological profile, tissue distribution and effector coupling (FIG. 1). All four subtypes are members of the superfamily of G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), and are most closely related to the receptors for biogenic amines. Among the human ARs, the most similar are the A1 and A3 ARs (49% sequence similarity) and the A2A and A2B ARs (59% similarity).

Figure 1. Adenosine receptor signalling pathways.

Activation of the A1 and A3 adenosine receptors (ARs) inhibits adenylyl cyclase activity through activation of pertussis toxin-sensitive Gi proteins and results in increased activity of phospholipase C (PLC) via Gβγ subunits. Activation of the A2A and A2B ARs increases adenylyl cyclase activity through activation of Gs proteins. Activation of the A2AAR to induce formation of inositol phosphates can occur under certain circumstances, possibly via the pertussis toxin-insensitive Gα15 and Gα16 proteins. A2BAR-induced activation of PLC is through Gq proteins. All four subtypes of ARs can couple to mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), giving them a role in cell growth, survival, death and differentiation. CREB, cAMP response element binding protein; DAG, diacylglycerol; IP3, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; PIP2, phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate; PK, protein kinase; PLD, phospholipase D; NF-κB, nuclear factor-κB.

Extracellular adenosine levels are quite variable, depending on the tissue and the degree of stress experienced, and so the basal levels of stimulation of the four subtypes by the endogenous agonist vary enormously. The sources of adenosine are either release through an equilibrative transporter or as a result of cell damage3, or nucleotidase-mediated hydrolysis of extracellular adenine nucleotides4, which have their own signalling properties that are mediated by purinergic P2 receptors. Ectonucleotidases, of which the apyrase CD39 and the 5′-nucleotidase CD73 are prominent examples, are present on the extracellular surface of many tissues and are crucially involved in numerous important functions4. For example, in the brain, CD73 is known as a marker of astrocytes (but not neurons). These enzymes rapidly and effectively shift signalling by released adenine nucleotides and their products to signalling through ARs. Astrocytederived adenosine, acting on A1ARs, has a central role in the integration of synaptic activity by astrocytes that leads to widespread coordination of synaptic networks5. Adenosine itself is rapidly metabolized by adenosine kinase6 and, to a lesser degree, adenosine deaminase to AMP and inosine, respectively, both of which are less active than adenosine at the ARs.

The development of potent and selective synthetic agonists and antagonists of ARs has been the subject of medicinal chemistry research for more than three decades. In addition, allosteric enhancers of agonist action could allow the effects of endogenous adenosine to be selectively magnified in an event-responsive and temporally specific manner, which might have therapeutic advantages compared with agonists7. AR action might also be modulated not only by direct-acting ligands, but by inhibition of the metabolism of extracellular adenosine6 or its cellular uptake3.

Although the basic science suggests that selective AR modulators have promise for numerous therapeutic applications, including cardiovascular, inflammatory and neurodegenerative diseases, in practice this goal has been elusive. One reason for this is the ubiquity of ARs and the possibility of side effects. In addition, species differences in the affinity of putatively selective ligands complicate preclinical testing in animal models. However, there has been a recent impetus towards novel clinical targets, in part as a result of the discovery of the A3AR subtype in the early 1990s and of the elucidation of new roles for adenosine. In this review, we first present an overview of AR signalling, and summarize progress in the development of selective AR modulators. We then discuss the roles of the AR subtypes in disease, and preclinical and clinical results with AR modulators in various conditions.

AR signalling pathways and regulation

Classically, AR signalling is thought to occur through inhibition or stimulation of adenylyl cyclase (also known as adenylate cyclase), although it is now apparent that other pathways, such as phospholipase C (PLC), Ca2+ and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), are also relevant (FIG. 1).

Activation of the A1AR inhibits adenylyl cyclase activity through activation of pertussis toxin-sensitive G proteins8,9 and results in increased activity of PLC10,11. In cardiac muscle and neurons, A1ARs can activate pertussis toxin-sensitive K+ channels, as well as KATP channels, and inhibit Q-, P- and N-type Ca2+ channels1. Coupling to K+ channels in supraventricular tissue is responsible for the bradycardiac effect of adenosine on heart function12. In the heart, A1AR and A2AAR agonistinduced preconditioning has been suggested to occur via modulation of p44/42 extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase (ERK) signalling13.

Activation of the A2AAR increases adenylyl cyclase activity. Gs seems to be the major G-protein associated with A2AARs in the peripheral systems but not in the striatum, where A2AAR density is the highest. It has been shown that striatal A2AARs mediate their effects predominantly through activation of Golf14, which is similar to Gs and also couples to adenylyl cyclase. In rat tail artery, facilitation of noradrenaline release by activation of the A2AAR triggers the PLC and adenylyl cyclase pathways15. Activation of the A2AAR also induces formation of inositol phosphates to raise intracellular calcium and activate protein kinase C in COS-7 cells via pertussis toxin-insensitive Gα15 and Gα16 proteins16, which have limited tissue distribution and interact with most GPCRs.

The A2BAR is positively coupled to both adenylyl cyclase and PLC17–20. Results indicate that the activation of PLC, through Gq proteins, mediates many of the important functions of A2BARs21,22. Activation of the A2BAR by the non-selective agonist NECA increased inositol phosphate formation in human mast cell line HMC-1 (REF. 20), which is not sensitive to cholera or pertussis toxin but is antagonized by the slightly A2BAR-selective antagonist enprofylline (3-propylxanthine)20. The arachidonic acid pathway was also recently demonstrated to be involved in A2BAR activation23.

The A3AR couples to classical second-messenger pathways such as inhibition of adenylyl cyclase24, stimulation of PLC25 and calcium mobilization26–29. In cardiac cells, A3AR agonists induce protection through the activation of KATP channels30. RhoA–phospholipase D1 signalling has been demonstrated to mediate the antiischaemic effect of A3ARs31. The WNT signalling pathway is involved in A3AR agonist-mediated suppression of melanoma cells32. In addition, like other ARs, the A3AR couples to MAPK, which could give it a role in cell growth, survival, death and differentiation33,34. An A3AR agonist inhibits proliferation in A375 human melanoma cells via the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase–protein kinase B–ERK1/2 pathway35.

Phosphorylation and subsequent desensitization of ARs have been studied for all four subtypes. The rapidity of the desensitization depends on the subtype, with the A3AR being more rapidly desensitized than the other subtypes36. GPCR kinase-mediated mechanisms are thought to have a crucial role in the rapid desensitization of A2A and A2BARs36.

AR agonists and antagonists

The main approach for discovering AR agonists has been modification of adenosine itself, and the structure–activity relationships of adenosine at ARs have been extensively probed37. Most of the useful analogues are modified in the N6- or 2-position of the adenine moiety and in the 3′-, 4′- or 5′-position of the ribose moiety. Highly selective agonists of the various receptor subtypes (FIGS 2,3; TABLE 1) have been designed through both empirical approaches and a semi-rational approach based on molecular modelling38,39.

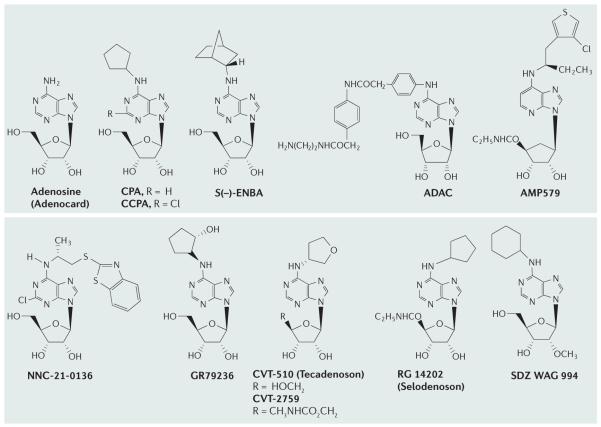

Figure 2. Adenosine receptor agonists.

Adenosine receptor (AR) agonists acting at the A1AR. Ki values for binding to ARs are given in TABLE 1.

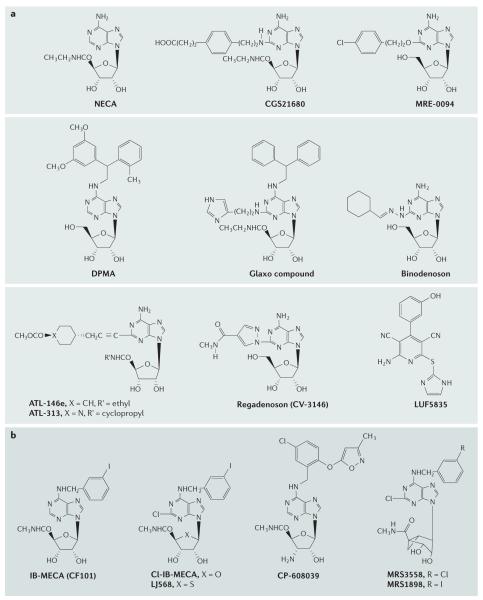

Figure 3. Adenosine receptor agonists.

a ∣ Adenosine receptor (AR) agonists acting at the A2AAR. LUF5835 (EC50 of 10 nM) is an atypical A2BAR agonist52. b ∣ AR agonists selective for the A3AR. Ki values for binding to ARs are given in TABLE 1.

Table 1.

Affinity of selected adenosine receptor agonists and antagonists at the four receptor subtypes

| Adenosine receptor subtype |

Compound | Ki value for AR (nM) | Refs | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1AR* | A2AAR* | A2BAR* | A3AR* | |||

| Agonists | ||||||

| A1 | CPA | 2.3 | 794 | 18,600¶ | 72 | 37,43,207 |

| CCPA | 0.83 | 2,270 | 18,800¶ | 38 | 37,43,207 | |

| S(–)-ENBA | 0.38 | >10,000 | >10,000¶ | 915 | 43 | |

| ADAC | 0.85‡ | 210‡ | N.D. | 13.3 | 43 | |

| AMP579 | 5.1‡ | 56‡ | N.D. | N.D. | 37 | |

| NNC-21-0136 | 10‡ | 630‡ | N.D. | N.D. | 135 | |

| GR79236 | 3.1‡ | 1,300‡ | N.D. | N.D. | 135 | |

| CVT-510 (Tecadenoson) | 6.5§ | 2,315§ | N.D. | N.D. | 37,66 | |

| SDZ WAG 994 | 23§ | 25,000§ | >10,000§,¶ | N.D. | 37,67 | |

| Selodenoson | 1.1‡ | 306‡ | N.D. | N.D. | 37,65 | |

| A2A | NECA | 14 | 20 | 140¶ | 25 | 43,207 |

| CGS21680 | 289 | 27 | >10,000¶ | 67 | 43,207 | |

| DPMA | 168 | 153 | >10,000¶ | 106 | 43,46 | |

| Binodenoson | 48,000 | 270 | 430,000¶ | 903 | 37 | |

| ATL-146e | 77 | 0.5 | N.D. | 45 | 37,45 | |

| CV-3146 | >10,000 | 290 | >10,000¶ | >10,000 | 208 | |

| A2B | LUF5835 | 4.4 | 21 | 10¶ | 104 | 52 |

| A3 | IB-MECA | 51 | 2,900 | 11,000¶ | 1.8 | 43,56,207 |

| Cl-IB-MECA | 220 | 5,360 | >100,000¶ | 1.4 | 39,43,207 | |

| LJ568 | 193 | 223 | N.D. | 0.38 | 58 | |

| CP-608039 | 7,200 | N.D. | N.D. | 5.8 | 78 | |

| MRS3558 | 260 | 2,300 | >10,000¶ | 0.29 | 39 | |

| MRS1898 | 136 | 784 | N.D. | 1.5 | 39 | |

| Antagonists | ||||||

| A1 | DPCPX | 3.9 | 129 | 56 | 3,980 | 40 |

| WRC-0571 | 1.7 | 105 | N.D. | 7,940 | 44 | |

| BG 9719 | 0.43 | 1,051 | 172 | 3,870 | 40 | |

| BG 9928 | 29 | 4,720 | 690 | 42,110 | 161 | |

| FK453 | 18 | 1300 | 980 | >10,000 | 194 | |

| FR194921 | 2.9 | >10,000 | N.D. | >10,000 | 107 | |

| KW3902 | 1.3‡ | 380‡ | N.D. | N.D. | 40 | |

| A2A | KW6002 | 2,830 | 36 | 1,800 | >3,000 | 124 |

| CSC | 28,000‡ | 54‡ | N.D. | N.D. | 40 | |

| SCH 58261 | 725 | 5.0 | 1,110 | 1,200 | 124 | |

| SCH 442416 | 1,110 | 0.048 | >10,000 | >10,000 | 152 | |

| ZM241,385 | 774 | 1.6 | 75 | 743 | 40,124 | |

| VER 6947 | 17 | 1.1 | 112 | 1,470 | 124 | |

| VER 7835 | 170 | 1.7 | 141 | 1,931 | 124 | |

| ‘Schering compound’ | 82 | 0.8 | N.D. | N.D. | 125 | |

| A2B | MRS1754 | 403 | 503 | 2.0 | 570 | 53 |

| MRE 2029-F20 | 245 | >1,000 | 3.0 | >1,000 | 54 | |

| OSIP-339391 | N.D. | N.D. | 0.5 | N.D. | 55 | |

| A3 | OT-7999 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | 0.61 | 200 |

| MRS1292 | 12,100‡ | 29,800‡ | N.D. | 29.3 | 42 | |

| PSB-11 | 1640 | 1,280 | 2,100¶ | 3.5 | 61 | |

| MRS3777 | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000¶ | 47 | 62 | |

| MRS1334 | >100,000 | >100,000 | N.D. | 2.7 | 56 | |

| MRE 3008-F20 | 1,200 | 141 | 2100 | 0.82 | 40 | |

| MRS1220 | 305‡ | 52.0‡ | N.D. | 0.65 | 56 | |

| MRS1523 | 15,600‡ | 2,050‡ | N.D. | 18.9 | 40 | |

| ‘Novartis compound’ | 197 | 1,670 | 3.0¶ | 10.0 | 175 | |

Binding experiments at recombinant human A1, A2A, A2B and A3 adenosine receptors (ARs), unless noted.

Binding experiments at rat ARs.

Binding or functional experiments at porcine ARs.

Data are from a cyclic AMP functional assay. N.D., not determined or not disclosed.

Similarly, the main approach for the discovery of AR antagonists (FIGS 4,5) has been modification of xanthines such as caffeine and theophylline40. A modelling approach combining quantitative models of receptor and ligand has been demonstrated to accurately predict the potency of antagonists41. Molecular modelling of ARs using information from the crystal structure of the seventransmembrane protein rhodopsin, supported by mutagenesis studies, has also aided in understanding ligand recognition and provided insights into conformational dynamics38,42.

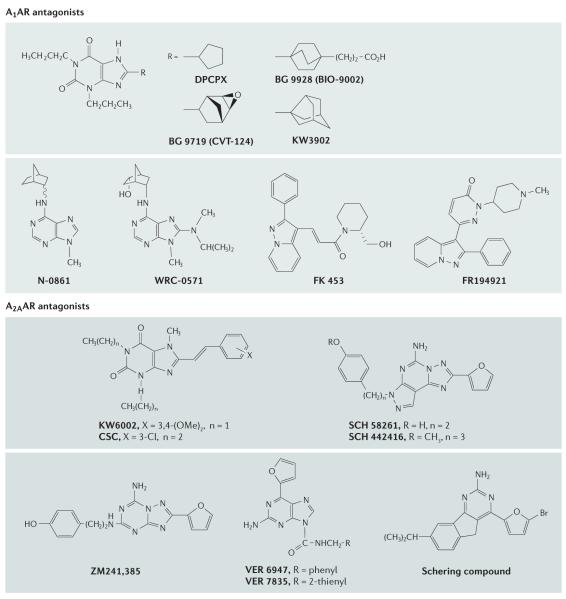

Figure 4. Adenosine receptor antagonists.

Antagonists acting at the A1 adenosine receptors (A1ARs) and A2AARs. Ki values for binding to the ARs are given in TABLE 1.

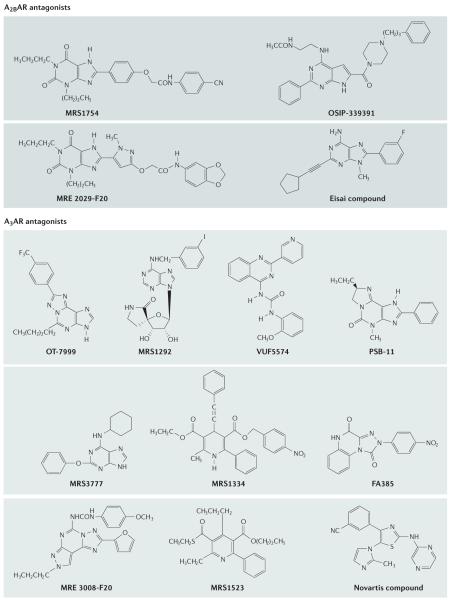

Figure 5. Adenosine receptor antagonists.

Antagonists acting at the A2B and A3 ARs40. Novartis compound has high affinity at human A2B and A3 ARs175. Ki values for binding to the ARs are given in TABLE 1.

The rest of this section summarizes the development of selective agonists and antagonists for each of the receptor subtypes.

A1 ARs

Agonist selectivity for A1ARs is typically accomplished through substitution at the adenosine N6-position, giving rise to compounds such as CPA. The 2-chloro analogue CCPA displays slightly greater A1AR affinity than the parent compound CPA. The affinities of these N6-substituted derivatives for A3ARs are often intermediate between their respective A1AR and A2AAR affinities. Agonists CPA and CCPA are highly selective for the rat A1AR compared with the A3AR subtype, but less selective in human tissue. S(–)-ENBA is an even more potent and selective agonist for human and rat A1ARs compared with the three other AR subtypes43

The classical, nonselective xanthine antagonists of ARs, theophylline (1,3-dimethylxanthine) and caffeine (1,3,7-trimethylxanthine), display micromolar affinity at A1, A2A and A2B ARs1. Potent and selective antagonists for A1ARs have been derived by modification of the xanthines, including many 8-aryl and 8-cycloalkyl derivatives40. One such derivative is DPCPX, which is highly selective for rat A1AR compared with the A2AAR (~500-fold) and less selective at the human A1ARs compared with human A2A and A2B ARs. Certain non-xanthine antagonists, such as the inverse agonist WRC-0571, derived from adenine, are A1AR selective, even compared with the A2BAR44.

A2A ARs

Substitution with small alkyl amide groups at the 5′-position of adenosine, as in the non-selective agonist NECA, provides increased potency at all the ARs, and this approach was also used to generate CGS21680, which is a moderately A2AAR-selective agonist in rats (140-fold selectivity for the A2AAR compared with the A1AR) but not humans1,43. The selective agonist ATL-146e has much greater affinity for the A2AAR than CGS2168045. Although most N6-substituted adenosine agonists are A1AR- or A3AR-selective, the agonist DPMA (diastereomeric pair) is more than 30-fold selective for the rat A2AAR compared with the rat A1AR and A3AR subtypes, but has similar affinity at human A1, A2A and A3 ARs43,46.

ZM241,385 and SCH 58261 are highly potent and selective A2AAR antagonists47,48, although ZM241,385 has been shown to bind with intermediate affinity at the human A2BAR46,47. The phenolic group of ZM241,385 can be radio-iodinated to provide an A2AAR-selective radioligand49. KW 6002, CSC and other 8-styrylxanthines are selective for A2AARs compared with the A1, A2B and A3ARs50. However, in dilute solution, these compounds suffer from sensitivity to photoisomerization.

A2B ARs

The A2BAR is the least studied subtype of the AR family51. Selective antagonists have been reported; however, adenosine derivatives as selective A2BAR agonists remain to be developed. Nearly all the known agonists are derivatives of adenosine. A notable exception is the development, on the basis of recent patents, of a series of pyridine-3,5-dicarbonitrile derivatives by IJzerman and colleagues52. These compounds act as AR agonists or partial agonists, with varying degrees of AR selectivity52, with LUF5835 being the most potent activator of the A2BAR (EC50 of 10 nM, FIG. 3a).

Xanthines that have been developed as selective antagonists of the A2BAR include MRS1754 and MRE 2029-F20, both of which have been prepared as radioligands53,54. Another selective antagonist, [3H]OSIP339391, has also recently been radiolabelled for the study of A2BARs55

A3 ARs

The prototypical A3AR agonist IB-MECA (CF101) and the more selective agonist Cl-IB-MECA have been widely used as pharmacological probes in the elucidation of the physiological role of the most recently identified AR subtype, A3 (REF. 56). IB-MECA has a ~50-fold selectivity for rat A3ARs over other subtypes in vitro. The related 4-aminobenzyl derivative can be radio-iodinated, giving rise to [125I]-I-AB-MECA, which is widely used as a high-affinity radioligand for A3ARs57

The 4′-thio modification of adenosine derivatives, explored for its effect on AR selectivity, has produced several highly potent and selective A3AR agonists, such as LJ568 (REF. 58). Conformational studies of the ribose moiety and its equivalents indicate that the ring oxygen is not required and that the North (N) ring conformation is preferred in binding to the A3AR. One means of locking the conformation of the ribose-like ring is through use of the bicyclo[3.1.0]hexane ring system, which assumes an (N)-envelope conformation39,42. Highly selective A3AR agonists were recently reported in the series of (N)-methanocarba-5′-uronamide derivatives, including MRS3558, which has a Ki value of 0.29 nM for the human A3AR39

The search for A3AR antagonists began with the discouraging observation that xanthines – such as caffeine and theophylline, the classical antagonists of A1, A2A and A2B ARs – typically have low binding affinities for the A3 AR24. Initial findings were reported for rat A3AR (before the report of the cloning of the human homologue) and many common xanthines have binding affinities of around 100 μM for this receptor. The cloning of the A3AR from other species facilitated further investigation of this receptor59. For sheep and human A3ARs, xanthines have intermediate affinity (typically 100 nM for 8-phenylxanthine analogues). There is a marked species dependence of antagonist affinity at the A3AR, with human affinity typically greatly exceeding that at the rat receptor for xanthine and other non-purine A3AR antagonists24,60. Therefore, the search for A3AR antagonists turned towards more novel heterocyclic systems56.

The screening of diverse chemical libraries resulted in the identification of new high-affinity hits for the human A3AR, including dihydropyridines, flavonoids, pyridines, thiazoles and others, which were then optimized, typically by substitution of aromatic rings40,41,56. The dihydropyridine derivative MRS1334 (not active at L-type calcium channels) and the pyridylquinazoline VUF5574 (not selective in rat) are both relatively potent A3AR antagonists, with Ki values of 2.7 and 4.0 nM, respectively, at the human subtype. The pyridine derivative MRS1523 is a selective A3AR antagonist in both rat and human. PSB-11, which is a selective antagonist for human A3ARs, was tritiated for characterization of this receptor61. Numerous adenine derivatives have been studied as selective antagonists for A1 or A2A ARs, and the adenine derivative MRS3777 was recently reported to be highly selective for the human A AR62

An alternative approach to designing A3AR antagonists is to start with high-affinity adenosine derivatives and truncate the molecule in stages to remove the capacity to activate the receptor without compromising high-affinity binding. An initial attempt to find adenine derivatives, such as 9-alkyl-N6-iodobenzyladenines, that displayed these characteristics was unsuccessful56. A more successful approach either added substituents to adenosine derivatives or rigidified the nucleosides, to reduce their intrinsic efficacy42. With more systematic studies of structure–efficacy relationships on substitution of adenosine at the N6, ribose and C2 adenine positions, it became apparent that the efficacy at A3ARs is more easily diminished by structural modification than it is at the other AR subtypes42,43. In some cases, N 6-substitution of adenosine 5′-OH derivatives with large groups (for example, substituted benzyl groups or large cycloalkyl rings) reduced the maximal efficacy, leading to decreased efficacy at the A3AR. For example, CCPA and DPMA, which are full agonists at A1 and A2A ARs, respectively, are A3AR antagonists. This structural insight was used advantageously to obtain the conformationally constrained nucleoside MRS1292, which proved to be a selective A3AR antagonist in both rat and human42,60.

ARs as targets in cardiovascular disease

Arrhythmia

A1AR activation has a number of effects in the cardiovascular system, including a reduction in heart rate and atrial contractility, and the attenuation of the stimulatory actions of catecholamines on the heart63,64. Activation of the A1AR by intravenous infusion of adenosine (Adenocard; Astellas Pharma) is used to restore normal heart rhythm in patients with paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia (PSVT). However, for more long-term indications, selective A1AR modulators are needed to avoid side effects related to other AR subtypes such as hypotension.

Selodenoson (DTI0009, GR 56072, RG 14202; Aderis Pharmaceuticals) is a potent and selective A1AR agonist with the potential to control heart rate without lowering blood pressure65. It has been tested in Phase II clinical trials for its capacity to slow heart rate in atrial fibrillation, although it has been reported to have renal toxicity. Tecadenoson (CVT-510) is a potent A1AR agonist with a dose-dependent negative dromotropic effect on the AV node66. In patient trials (now Phase III), it terminated PSVT without the side effects associated with other AR subtypes, such as hypotensive effects. CVT-2759 is a partial agonist of the A1AR, which in guinea pig heart seems to be useful in slowing down AV nodal conduction and thereby ventricular rate without causing AV block, bradycardia, atrial arrhythmias or vasodilation63. SDZ WAG 994 was extensively characterized in clinically relevant models67 and has been in Phase I clinical trials for the potential treatment of PSVT. However, development of this agent was discontinued in 1999.

Ischaemia

Adenosine is released in large amounts during myocardial ischaemia, resulting in effective pre-conditioning in cardiomyocytes through the activation of A1 and A3 ARs29–31,68. Administration of a synthetic AR agonist to activate either or both of these receptors might therefore be beneficial to the survival of the ischaemic heart.

Ischaemic cardiac preconditioning by the A1AR involves a series of intracellular events that begin with the activation of the receptor and end at the sensitive K +-ATP channels of the mitochondria. Most of the pharmacological data indicate that A1ARs have an important role in protection of the heart and brain from ischaemia–reperfusion injury1. The A1AR-agonist-induced decreases in blood pressure and heart rate are mediated by the peripheral A1ARs, with little or no contribution of central A1ARs, which is consistent with the observation that typical agonists cross the blood–brain barrier to only a small degree69. An important role of the A1AR in protection of the murine heart by remote, delayed adaptation has been demonstrated70.

Cardiac overexpression of A1ARs in mouse heart results in substantial protection from ischaemia–reperfusion injury71–73. Hearts isolated from transgenic animals with overexpression of A1ARs have a lower basal rate than those of control mice71. Cardioprotection in wild-type hearts and hearts overexpressing A1ARs was mediated by mitochondrial K+-ATP channel activation74. A1AR overexpression also improves myocardial tolerance to anoxia reoxygenation, in addition to protecting hearts from ischaemia–reperfusion injury75. The cardiovascular effects of the A1AR agonist CPA also convey protection against Sarin poisoning76.

It is well documented that adenosine can protect tissues against hypoxia or ischaemia through A1ARs. In the A1AR-knockout mouse heart, baseline contractile function and heart rate were unaltered, but intrinsic myocardial resistance to ischaemia was limited77. In addition, non-selective receptor agonism induced by 2-chloroadenosine was cardioprotective in A1AR-knockout (albeit to a lesser extent) and wild-type hearts, indicating additional protective mechanisms through other AR subtypes.

Various lines of evidence indicate that the A3AR has a role in protecting the heart68,78. Overexpression of A3ARs decreases heart rate, preserves energetics and protects ischaemic hearts79, and low-level expression of A3ARs in the heart provides effective protection against ischaemic injury without detectable adverse effects, although higher levels of A3AR expression lead to the development of a dilated cardiomyopathy80. Paradoxically, global deletion of the A3AR in mice also confers resistance to myocardial ischaemic injury and does not prevent early preconditioning81. In an isovolumic Langendorff perfusion model, A3AR-knockout mice also had improved functional recovery and tissue viability during reperfusion after ischaemia when compared with control mice78. In one study, administration of an A3AR agonist in wild-type and A3AR-knockout mice showed similar cardioprotective effects: post-ischaemic recovery was enhanced in A3AR-knockout mice82, implying action of the agonist at a non-A3AR, probably the A2AAR. It has been demonstrated that, in addition to the role of A1 and A3AR agonists, the A2AAR activation is protective against ischaemia–reperfusion injury in mice, which has been proposed to be mainly due to its actions on lymphocytes83.

An A3AR-mediated direct cardioprotective effect has been evident31. However, the A3AR expression level is low in cardiomyocytes. So, an indirect protective effect has also been proposed, for example, through modulation of the function of mast cells and neutrophils, in which A3ARs are abundant. A3AR signalling in rodent mast cells may be detrimental to the myocardium because of a pro-inflammatory mechanism, but this response might only be observed in rodents (that is, mouse A3AR-knockout experiments) because mast cell degranulation seems to be A2BAR-dependent in humans and dogs1. This could at least in part explain the paradoxical effects observed in various experiments75,81,82. Another explanation of the paradoxical effect could be the numerous compensatory mechanisms observed in receptor-knockout mice84.

Some studies have shown that activation of either A1 or A3 ARs could trigger protection of function in preconditioned rat hearts, although maximal preconditioning requires activation of both A1 and A3 ARs85,86. The selective agonists CCPA and Cl-IB-MECA have been used to discern two separate A1 and A3AR-mediated pathways leading to cardioprotection, either as early or late preconditioning or during prolonged ischaemia. Unlike the case of A1AR-mediated cardioprotection, A3AR-mediated cardioprotection is achieved in vivo in the absence of haemodynamic side effects, such as hypotensive effects, and could therefore be therapeutically more promising68. Stimulation of A3ARs could also be advantageous over A1AR activation because it may be less likely to induce bradycardia85. The A3AR agonist CP608039 is in development for use in perioperative cardioprotection78, and the A3AR agonist Cl-IB-MECA protects rat cardiac myocytes from the toxicity induced by the cancer chemotherapeutic agent doxorubicin87.

Vasodilation

The A2AAR is involved in vasodilation in the aorta and coronary artery1. It was suggested that the tachycardic effect of A2AAR activation is mediated by centrally located receptors, whereas its hypotensive effect is mediated by the peripheral A2AAR69. In the late 1960s and 1970s, metabolically stable AR agonists were tested clinically as antihypertensives, and this was an intended use of the A2AAR agonist CGS21680; however, its clinical path was curtailed following canine haemodynamic studies due to in vivo non-selectivity related to spare receptors. In platelets, an A2AAR agonist was shown to inhibit aggregation by increasing intracellular cAMP levels, suggesting that adenosine agonists might have utility as antithrombotic agents88.

Recently, there has been an effort to further improve subtype-selectivity of A2AAR agonists for novel therapeutic applications, including imaging. Adenosine, under the name Adenoscan (Astellas Pharma), is used in myocardial stress imaging to evaluate coronary artery disease by achieving vasodilation in patients unable to exercise adequately. Regadenoson (CVT-3146), a potent and selective A2AAR agonist, is being evaluated in Phase III studies for the same purpose during myocardial perfusion imaging89. The selective A2AAR agonist binodenoson (WRC-0470) has entered Phase III clinical trials and seems to be well tolerated as a short-lived coronary vasodilator and acts as an adjunct to radiotracers in imaging90. ATL-146e, the most selective of these A2AAR agonists, has also entered Phase III clinical trials for coronary imaging.

Activation of the A2BAR induces vasodilation in some vascular beds91,92, such as the main pulmonary artery of guinea pigs, and induces human chorionic vasoconstriction and signals through the arachidonic acid cascade23. The A2BAR is selectively upregulated by hypoxia, and A2BAR antagonists effectively neutralize ATP-elicited reduction in post-hypoxic endothelial permeability93. Inhibition of mitosis of rat aortic smooth-muscle cells has been achieved through selective A2B AR activation94. The A2BARs are also important for adenosine-mediated inhibition of cardiac fibroblast functions95 and the stimulation of nitric oxide production during Na+-linked glucose or glutamine absorption96. Activation of the A2BAR promotes angiogenesis by increasing the release of angiogenic factors2,97.

Cutaneous vasopermeability, which is associated with activation and subsequent degranulation of mast cells, is completely lost in mice lacking functional A3ARs98. One of the well-known actions of adenosine is to dilate vascular beds. Interestingly, the concentration of cAMP is higher in the aortae of A3AR-deficient mice, with no significant change in the amount of A1 or A2A ARs, than it is in control mice. The hypotensive effect observed after intravenous adenosine injection in mice lacking the A3AR was significantly larger than in control mice99. Genetic deletion of the A3AR or antagonism of the A3AR augmented coronary flow induced either by adenosine or by the A2AAR agonist CGS21680 (REF. 100). However, A3ARs do not regulate atherogenesis; the development of atherosclerosis and response to injury of the femoral artery were similar to those in wild-type mice101.

It has been clearly demonstrated that both agonist- and antagonist-binding profiles for the murine and human A3ARs are different. The marked species difference, together with the paradoxical protection in A3AR-knockout hearts despite A3AR-mediated protection in wild-type hearts, could reflect limitations of gene-knockout studies, and the A3AR-knockout data from mice should be interpreted with caution. Also, it should be noted that the selective ligands currently available are only relatively selective for a certain AR subtype. At relatively high concentrations, these ligands may also activate or block other AR subtypes. As such, cautious and thoughtful interpretation of pharmacological data is necessary.

ARs as targets in nervous system disorders

Observations of the effects of caffeine — a classical AR antagonist — on the nervous system, such as enhancement of awareness and learning, have encouraged the investigation of selective AR antagonists in the nervous system. Indeed, the A1AR was recently shown to be involved in the discriminative-stimulus effects of caffeine102. However, it is the A2AAR, which was the first AR to be genetically deleted103, that is the primary mediator of the behavioural stimulatory effects of caffeine103–105, and this receptor also has an important role in sleep regulation (see below)106. Although high concentrations of caffeine can also block phosphodiesterases, which can have numerous behavioural consequences104, most of the varied stimulant and other behavioural effects of caffeine are thought to result from antagonism of ARs in the nervous system. This suggests that modulation of ARs may provide therapeutic targets in nervous system disorders, in such diverse conditions as dementia and other neurodegenerative diseases, hyperactivity, anxiety, schizophrenia and sleep disorders.

Dementia and anxiety disorders

Recently, the novel A1AR-selective antagonist FR194921 (which did not show any species differences in its high A1AR affinity) was reported to have potential in the treatment of dementia and anxiety disorders107. FR194921 was orally active and centrally available, ameliorated scopolamineinduced memory deficits, and also showed anxiolytic effects in the elevated plus maze test, without influencing general behaviour or having antidepressant activity107.

Pain

Adenosine exerts multiple influences on pain transmission at peripheral and spinal sites. At peripheral nerve terminals in rodents, A1AR activation produces antinociception by decreasing cAMP levels in the sensory nerve terminal108. Mice lacking functional A1AR show signs of increased anxiety and hyperalgesia, and the analgesic effects of adenosine observed in wild-type mice are lost109. A recent study using A1AR-knockout mice suggested that A1ARs might be more important in chronic pain than in acute pain110. In humans, infusion of adenosine in the spinal cord was effective in decreasing post-operative pain111.

The A1AR agonist GR79236 administered in cats had a dose-dependent inhibitory effect on trigeminovascular nociceptive transmission, which is otherwise associated with the initiation of local increases in blood flow and enhanced protein permeability — that is, factors that contribute to vascular headaches112. A1AR activation leads to neuronal inhibition without concomitant vasoconstriction, indicating that this might be an effective treatment of migraine and cluster headache. Another A1AR agonist, GW-493838, was evaluated in Phase II clinical trials for the treatment of pain and migraine, and was found to inhibit electrically induced nociceptionspecific blink reflex responses113. The A1AR-selective allosteric enhancer T-62 (FIG. 6) was also shown to reduce hypersensitivity in carageenin-inflamed rats by a central mechanism114. T-62 has entered Phase I clinical trials as a treatment for neuropathic pain.

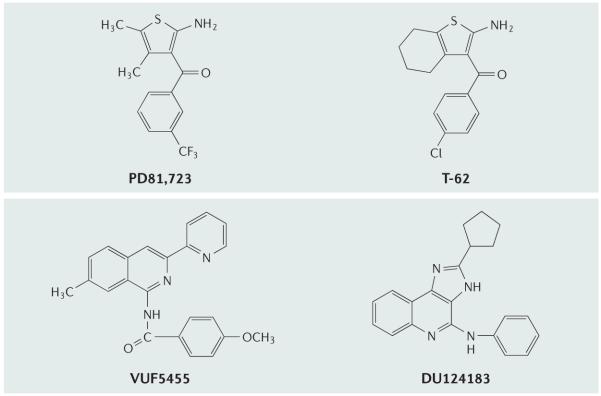

Figure 6. Examples of allosteric enhancers of the activity of adenosine receptor agonists.

PD81,723 and T-62 enhance the activity of agonists acting at the A1 adenosine receptor (A1AR) and VUF5455 and DU124183 enhance the activity of agonists acting at the A3 AR7.

Parkinson’s disease

Some of the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease are thought to be caused by a deficit in dopamine release in the striatum. Interestingly, in this respect, various lines of evidence indicate that interaction between the A2AAR and dopamine D2 receptors (D2Rs) in the striatum is antagonistic. The A2AAR is co-expressed with D2Rs in the striatum and heterodimerization of A2AAR and D R subtypes inhibits D2R function1,115. In SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells, A2AAR–D2R heteromeric complexes undergo co-aggregation and co-internalization as a result of long-term exposure to A2AAR or D2R agonists116. Independent action of the A2AAR and D2R has also been proposed in A2AAR-knockout studies117. In D2R-knockout mice, A2AAR agonists and antagonists produce behavioural and cellular functions that are similar to those of their wild-type counterparts, suggesting a D2R-independent mechanism118,119.

The possible antagonistic relationship between A2AARs and D2Rs in the striatum has provided a rationale for evaluating A2AAR antagonists in Parkinson’s disease. In addition, epidemiological evidence shows an inverse relationship between caffeine consumption and risk of developing Parkinson’s disease120,121. A2AAR antagonists not only provide symptomatic relief but also decelerate the neurodegeneration of dopaminergic cells in patients with Parkinson’s disease119. An A2AAR antagonist, KW-6002 (istradefylline), has shown potential in a recently completed Phase II clinical trial (now in Phase III trials) as a novel treatment for Parkinson’s disease123,124, and other A2AAR antagonists, such as V2006 (a derivative of the antimalarial drug mefloquine), are in development124–126. V2006, which is beginning Phase II clinical trials, is well tolerated in high doses, and its pharmacokinetic properties suggest that it should be suitable for daily dosing.

Ischaemia and neuroprotection

Pharmacological characterization of A2AAR-knockout mice has shown that A2AAR inactivation protects against neuronal cell death induced by ischaemia127,128 and the mitochondrial toxin 3-NP (an animal model of Huntington’s disease)129. Yu et al.130 recently created a chimeric mouse model in which A2AAR knockout is combined with bone marrow transplantation. Selective reconstitution of A2AARs in bone marrow cells of A2AAR-knockout mice abolished the neuroprotection against ischaemic brain injury in global A2AAR-knockout mice. Conversely, selective inactivation of A2AARs by transplantation of bone marrow cells-derived cells from A2AAR-knockout mice into wild-type mice attenuated infarct volumes and ischaemia-induced expression of several pro-inflammatory cytokines in the brain. The finding indicated the possible use of A2AARs on bone marrow-derived cells for the treatment of ischaemic brain injury. In contrast to adult mice, in newborn A2AAR-knockout mice, brain damage is aggravated after hypoxic ischaemia131.

The seemingly paradoxical protective effects of both A2AAR agonism and antagonism indicate the degree of complexity of the system, and the dependence of the results on developmental stage and the specific mechanism of injury. Studies have also shown that A2AAR agonists result in neuroprotection in some experimental conditions, including cerebral haemorrhagic injury132 and ischaemia–reperfusion injury in the spinal cord133.

In the brain, adenosine released under stress conditions counteracts the release and damaging effects of excitatory neurotransmitters, such as glutamate, by activation of the A1AR. ADAC, an A1AR agonist, was potent in cerebroprotection in a model of global ischaemia in gerbils134. The A1AR agonist NNC-21-0136 was neuroprotective in both global and focal rodent ischaemia models and had diminished cardiovascular effects in rats compared with reference A1 AR agonists, such as CPA135. However, it was recently shown that deletion of the gene that encodes the A1AR does not alter neuronal damage that occurs after ischaemia in vivo or in vitro136, although A1ARs have been shown to be relevant to hypoxia protection in newborn mice137. Glial cells express all the ARs, and A2AAR activation was found to promote myelination in Schwann cells, suggesting that a selective agonist could be useful in treating demyelinating diseases such as multiple sclerosis138. Although A3AR expression levels are low in all regions of the brain139–141, an A3AR agonist (IB-MECA) depresses locomotor activity in mice142, suggesting a role for the A3AR in depression of motor activity. Chronic administration of the A3AR agonist IB-MECA was highly effective in a gerbil model of cerebroprotection against global ischaemia143, and deletion of the A3AR has a detrimental effect in a model of mild hypoxia, suggesting the possibility of using A3AR agonists to treat cerebral ischaemia.

Sleep

Adenosine has been found to be an important endogenous sleep-promoting substance144,145. It mediates the somnogenic effects of prior wakefulness, and also seems to have an important role in the regulation of the duration and depth of sleep after wakefulness144.

Pharmacological data suggest that A1ARs are involved in the regulation of sleep145, but lack of A1ARs does not prevent the homeostatic regulation of sleep146. Therefore, it is possible that although the A1AR is an important factor for sleep regulation in normal animals, other factors, such as the A2AAR, could compensate for the role of A1AR when it is deleted. Indeed, it was recently shown that the A2AAR has a key role in adenosine-mediated sleep-promoting effects147. It has been suggested that the cholinergic basal forebrain is an essential area for mediating the sleep-inducing effects of adenosine by inhibition of wakefulness-promoting neurons via the A1AR, and the A2AAR in the subarachnoid space below the rostral forebrain could have a role in the prostaglandin D2R-mediated somnogenic effects of adenosine148. The arousal effect of caffeine was recently shown to be dependent on the A2A AR105. However, the locomotor stimulatory effect of high doses of caffeine is not the result of the blockade of either the A1AR or the A2AAR, and an effect that is independent of AR activity is probable104. Although the concept of using AR agonists as modulators for sleep disorders is intriguing, in practice this would be dependent on brain-selective receptor activation.

Other potential applications

Adenosine is important in mediating at least some of the neuronal responses to ethanol149,150. Ethanol increases brain levels of adenosine by inhibiting adenosine reuptake, which activates A2AARs and thereby raises cAMP concentrations. The resulting activation of protein kinase A leads to activation of cAMP response element (CRE)-mediated gene expression. Alcohol and adenosine therefore interact synergistically with the activation of D2Rs in median spiny neurons of the striatum/nucleus accumbens, unlike the otherwise antagonistic relationship between dopamine and adenosine. This is thought to involve the G-protein β,γ dimers, the inhibition of which reduces voluntary alcohol consumption. Therefore, drugs that antagonize the synergism of A2AAR and D2R effects might be useful in controlling alcohol abuse.

There has also been recent progress in the imaging of ARs in the brain. An 18F analogue of DPCPX has been developed as a positron-emission tomographic imaging agent151. The highly potent and selective A2AAR antagonist SCH442416 in 11C-labelled form has been established as an in vivo receptor-imaging agent in the rat and primate brain, which may eventually strengthen the link between the A2AAR and disease states, as well as aid in identifying those patients that are likely to benefit from adenosine-related therapeutics152.

Finally, blockade of A2AAR has a clear antidepressant effect153, suggesting that selective A2AAR antagonists could be pursued as antidepressant drugs. A1AR activation has also been a target in the development of antiepileptic therapy6, and an inhibitor of adenosine kinase was shown to inhibit seizure activity in animals6.

ARs as targets in renal system disorders

Activation of A1AR protected against ischaemia– reperfusion-induced kidney injury154. Pretreatment of C57BL/6 mice with an A1AR antagonist caused a significant deterioration in renal function154. In addition, A1AR expression protects renal proximal tubular epithelial cells against cisplatin-mediated apoptosis155. Mice lacking A1ARs showed a completely blocked renal glomerular filtration rate by a tubuloglomerular feedback mechanism156,157, and A1AR-knockout mice had increased renal injury after ischaemia and reperfusion158. Therefore, the kidney protective effect of A1AR agonists has been evident, which provides the basis for their future development as drugs for the treatment of renal failure.

Unlike A1AR agonists, A1AR antagonists are effective diuretic agents that are useful in treating fluid-retention disorders, including congestive heart failure, although antagonism of A1ARs is potentially a concern when using these agents in patients with ischaemic heart and kidney injury. An A1AR antagonist, BG9719 (CVT-124), was in Phase II clinical trials (now discontinued) for the treatment of acute renal disorders in patients with congestive heart failure159,160. However, BG9719 contains an epoxide group, which is potentially chemically reactive. However, a non-epoxide-containing antagonist in the same series, BG9928, improves renal function and congestive heart failure without exacerbating cardiac injury161. BG9928, now in Phase II clinical trials, was found to improve sodium excretion in heart failure patients.

A2AAR agonist-mediated cellular protection is particularly evident in peripheral tissues, including the kidney2. The A2AAR in bone marrow-derived cells is also responsible for protection against ischaemic injury in the kidney162. A recently developed A2AAR agonist, ATL-146e, was shown to protect against ischaemic renal injury163, and the mixed A1/A2AAR agonist AMP579 was initially tested in patients with end-stage renal insufficiency; however, further clinical testing of the compound is impossible due to its inhibition of HERG channels164.

The expression of the A AR in the kidney165 2B and the presence of endogenous A2BARs in the HEK-293 cell line166 suggested a potential role in the kidney for this subtype, which is known to regulate cell growth and pro-liferation167. Finally, mice lacking the A3AR or wild-type mice in which the A3AR was blocked pharmacologically had significant renal protection168, suggesting that A3AR antagonists might have general renal-protective properties. Recent evidence suggested that both A1AR agonists and A3AR antagonists protect the kidney. Ligands possessing dual acting and opposite properties at these AR subtypes could therefore be effective therapeutic agents for renal protection.

ARs as targets in pulmonary disorders

A protective role for the A1AR in adenosine-dependent pulmonary injury has been proposed169. Genetic removal of the A1AR from adenosine deaminase-deficient mice caused enhanced pulmonary inflammation along with increased mucus metaplasia and alveolar destruction. The expression of TH2 cytokines interleukin-4 (IL-4) andIL-13 in the lungs, as well as chemokines and matrix metalloproteinases, was upregulated. These findings imply that A1AR agonists have potential for the therapeutic treatment of pulmonary injury.

In the asthmatic lung, adenosine acts as an irritant and bronchoconstrictor, and so a synthetic AR antagonist, perhaps selective for the A2BAR, could have therapeutic potential in asthma treatment170. In mouse mast cells, A3AR activation has been shown to induce mast-cell degranulation171. It has been suggested that this effect is mediated by the A2BAR in human and canine mast cells172–174. A bioavailable thiazole derivative that acts as a mixed antagonist at A2B and A3 ARs has been proposed to be a candidate therapeutic agent for the treatment of asthma175; however, this has not been tested in animal models. In addition, the bronchodilating, anti-asthmatic effects of theophylline and other xanthines might involve A2BAR blockade, although the evidence for this is controversial due to the lack of an adequate animal model. The lack of A2BAR-selective agonists and, until recently, A2BAR-knockout mice have hampered further clarification of the functional significance of this receptor.

Activation of the A2AAR by CGS21680 produces broad-spectrum anti-inflammatory activity in a model of allergic asthma in the Brown Norway rat, suggesting that A2AAR agonists could be useful alternatives to glucocor-ticosteroids in the treatment of asthma176. GW328267, an A2AAR agonist designed for intranasal administration, was also evaluated in Phase II clinical trials for upper respiratory inflammatory disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma; however, the results at the dose used were negative and the compound has been withdrawn from clinical testing177.

In preclinical testing, the A3AR agonist IB-MECA was shown to protect against lung injury and apoptosis in cats after reperfusion178, and this protection was antagonized by MRS1191, a dihydropyridine that is a selective A AR antagonist56

As described earlier, prominent species differences in the structure and function of ARs, especially the A3AR, have been observed. For example, human and rat A3ARs only share 72% overall identity at the amino-acid level; mast-cell degranulation is induced by the A2BAR in dogs and humans, but by the A3AR in mice. It is therefore plausible that some of the functions observed with one animal model might not be obtained in other animal models and in humans. Cross-species testing systems are necessary to validate the receptor function or effects of agonists and antagonists.

ARs as targets in inflammatory disorders

Adenosine-mediated activation of the A2AAR, which is found in almost all immune cells, including lymphocytes, monocytes, macrophages and dendritic cells179, seems to attenuate inflammation and reperfusion injury in a variety of tissues. Through A2AAR activation, adenosine can inhibit T-cell activation, proliferation and production of inflammatory cytokines while enhancing the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines. Activation of the A2AAR in TH and cytotoxic T lymphocytes directly inhibits IL-2secretion in vitro and IL-2-driven expansion in vivo180. In murine CD4+ T cells, the A2AAR agonists ATL-146e and ATL-313 were shown to reduce T cell-receptor (TCR)-mediated production of interferon-γ (IFNγ). Rapid-induction TCR signalling of the mRNA for the A2AAR suggests that this is a mechanism for limiting T-cell activation and secondary macrophage activation in inflamed tissues181.

Ohta and Sitkovsky182 reported that A2AARs are crucially involved in the limitation and termination of prolonged inflammation. Knockout of the A2AAR in mice showed that no other mechanism for inflammation could compensate fully for the loss of the A2AAR (which has been referred to as a brake for inflammation183) on immune cells. Interestingly, in knockout mouse models, the A2AAR together with the A3AR mediated the anti-inflammatory effect of methotrexate, which is used as a treatment of arthritis184. ATL-146e, a selective agonist of the A2AAR, profoundly protects mouse liver from reperfusion injury, and the protection is blocked by the A2AAR antagonist ZM241385. In mice lacking the A2AAR, protection by ATL-146e is lost and ischaemic injury of short duration is exacerbated, which contrasts with the results obtained in wild-type mice, suggesting a protective role for endogenous adenosine185. The A2AAR agonist ATL-146e is also of interest for the treatment of sepsis186, inflammatory bowel disease187 and for inclusion in drug-eluting stents to prevent restenosis after angioplasty. Selective activation of the A2AAR has also been shown to reduce skin pressure, ulcer formation and inflammation188, and wound healing is accelerated189.

The A3AR has been implicated in mediating allergic responses in mice; it facilitates the release of allergic mediators, such as histamine, in mast cells190. Systemic infusion of IB-MECA causes scratching in mice that is prevented by co-administration of histamine antagonists142. The potentiation by Cl-IB-MECA of antigen-dependent degranulation of mast cells, as measured by hexosaminidase release, was lost in mice lacking A3 ARs171. Attenuation of lipopolysaccharide-induced tumour-necrosis factor-α (TNFα) production was lower in mice lacking the A3 AR than in control mice171.

Finally, adenosine has been implicated in arthritis treatment, and the possibility of administration of A2A AR agonists for this purpose remains open191. The A3AR agonist IB-MECA also showed beneficial effects in early human trials192.

ARs as targets for endocrine disorders

A1AR agonists are under consideration as therapeutic candidates for obesity-related insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes193. In mice overexpressing the A1AR in adipose tissue, lower concentrations of plasma free fatty acids were observed than in litter-matched controls, and the transgenic mice did not develop insulin resistance. This supports a significant physiological role for adipocyte A1AR in the control of lipolysis. GR79236 has been tested in humans for adjuvant therapy in insulin resistance (type 2 diabetes). This A1AR agonist ameliorates the hypertriglyceridaemia induced by fructose feeding, and the reduction in fatty acid levels is associated with secondary improvements in glucose tolerance.

A2BAR antagonists are also under consideration for diabetes treatment. A 2-alkynyl-8-aryl-9-methyladenine derivative developed by Eisai showed hypoglycaemic activity in an animal model of type 2 diabetes, suggesting that adenosine agonist-induced glucose production in rat hepatocytes is mediated through the A2B AR194. The A2AAR agonist MRE-0094 is in Phase I clinical trials as a treatment for chronic diabetic neuropathic foot ulcers due to the anti-inflammatory and wound healing effects of A2AAR agonists.

ARs as targets in cancer

A3AR agonists can induce or attenuate apoptosis depending on the range of agonist concentrations used, which might have important implications for their therapeutic use in disorders in which the aim is to either attenuate apoptosis, such as arthritis (see above), or induce it, as in cancer. In human eosinophils and human promyelocytic HL-60 cells195,196 the A3AR agonist Cl-IB-MECA seems to induce apoptosis at relatively high concentrations (>10 μM), but in RBL-2H3 cells, a lower concentration (1 μM) of the A3AR agonist IB-MECA block apoptosis that is induced by ultraviolet irradiation197.

A role for the A3AR in mediating control of the cell cycle has been reported198. Activation of the A3AR by adenosine triggers a cell survival response; by contrast, activation of A2AARs induces an apoptotic signalling pathway that involves protein kinase C and MAPKs199. Overexpression of the A3AR in transgenic mice resulted in embryonic lethality141, suggesting the possible use of selective A3AR agonists in anticancer therapy.

A3AR activation has been implicated in inhibition of tumour growth both in vitro and in vivo200, and IB-MECA is in clinical trials for colon carcinoma. However, the novel anticancer effect discovered by Fishman and colleagues is caused by a cytostatic effect on tumours related to the WNT pathway32, rather than by induction of apoptosis. Recently, it was shown that the A3AR is more highly expressed in tumour than in normal cells, which may justify A3AR as a potential target for tumour growth inhibition201. In human breast cancer cell lines, IB-MECA downregulated the oestrogen receptor and completely inhibited cell growth202.

ARs as targets in visual disorders

The A3AR-knockout mouse had significantly lower intraocular pressure, suggesting that A3AR antagonists have potential in the treatment of glaucoma203. Most reported A3AR antagonists are selective only at the human A3AR, and so are not suitable for use in rodent models, but the selective A3AR antagonist OT-7999 reduced intraocular pressure in the monkey204. Encouragingly, the cross-species A3AR antagonist MRS1292 was recently found to reduce mouse intraocular pressure and also inhibited adenosine-triggered human non-pigmented ciliary epithelial cell fluid release60.

Conclusions

The medicinal chemistry of ARs is well developed, and selective agonists and antagonists have been generated for most of the receptor subtypes. In addition to the potential of directly acting orthosteric ligands, allosteric modulation of ARs is a promising approach. The application of genetic therapy with neoceptors could also potentially achieve organ or tissue selectivity in the future (BOX 1). With suitable pharmacological probes and the availability of knockout mice for three of the four subtypes, the basic science of ARs has progressed to the identification of novel therapeutic targets (FIG. 7). It is hoped that new agents in development will avoid the undesirable side effects that have impeded the clinical development of AR ligands in the past. Selective agonists are well advanced in clinical trials for the treatment of atrial fibrillation, pain, neuropathy, pulmonary and other inflammatory conditions, and cancer. Selective antagonists have entered clinical trials for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease and congestive heart failure. Both in the case of diseases such as stroke, where there is an unmet medical need, and for diseases that already have pharmacological intervention options, the introduction of adenosine-based drug therapy will provide novel mechanisms for therapy. With the maturing of AR science, it is time for some of the myriad of selective agents synthesized to be implemented in the fight to improve human health.

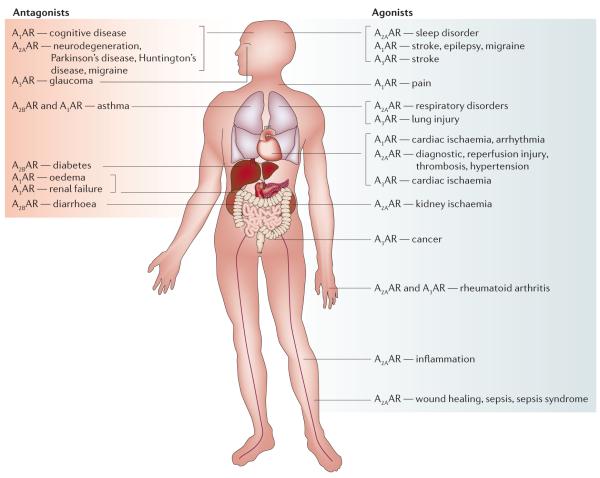

Figure 7. Novel disease targets for selective adenosine receptor ligands.

Most promising prospects exist for treatment of arrhythmias, ischaemia of the heart and brain, pain, neurodegenerative diseases, sleep disorders, inflammation, diabetes, renal failure, cancer and glaucoma, and in cardiovascular imaging. High and intermediate levels of A1 adenosine receptor (AR) expression were found in the brain, heart, adipose tissue, stomach, vas deferens, testis, spleen, kidney, aorta, liver, eye and bladder140. The A2AAR is highly expressed in the striatum, nucleus accumbens and olfactory tubercle140. High and intermediate expression levels were also found in immune cells, heart, lung and blood vessels. The A2B AR was generally expressed at low levels in almost all tissues140. Rat testis has particularly high concentrations of A3AR mRNA, with moderate levels in lung. The highest levels of human A3AR mRNA have been found in lung and liver. A3ARs have been detected in various tissues including testis, lung, kidney, placenta, heart, brain, spleen, liver, uterus, bladder, jejunum, aorta, proximal colon and eyes.

Box 1. Neoceptors.

Because of the widespread distribution of native adenosine receptors (ARs), their activation is inherently nonselective. To address this issue, efforts have been made to reengineer ARs into ‘neoceptors’ that can recognize uniquely modified nucleosides that are inactive at the native ARs38,205,206. This neoceptor strategy, which is intended for eventual use in organ-targeted gene therapy, is made possible by modelling of the putative ligand-binding site of a G-protein-coupled receptor, leading to identification of sites for mutagenesis, and incorporation of a complementary functional group in a synthetic agonist (neoligand). A novel electrostatic or H-bonding pair formed between the neoceptor and neoligand allows receptor activation that is orthogonal with respect to the native species209. So far, neoceptors have been developed for A2A and A3 ARs.

Glossary

- Angiogenesis

The growth of new blood vessels — for example, in pathology, the generation of a blood supply to a tumour.

- Allosteric site

A modulatory binding site on a receptor that is topographically distinct from the agonist binding site.

- Pertussis toxin

A compound that inhibits the guanine nucleotide binding proteins Gi and Go via ADP-ribosylation.

- Bradycardiac effect

An arrhythmia typified by an abnormally slow heart rate.

- Mast cell

A type of leukocyte that has large secretory granules that contain histamine and various protein mediators.

- Photoisomerization

A conversion between structural isomers caused by light-induced excitation.

- Paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia (PSVT)

A regular, abnormally fast heart beat caused by rapid firing of electrical impulses from a focus above the AV (atrioventricular) node.

- Atrial fibrillation

A condition in which disorganized electrical conduction in the atrial walls results in ineffective pumping of blood into the ventricle and an irregular heart rhythm.

- Dromotropic

Refers to velocity of AV nodal conduction in the heart.

- Discriminative stimulus

In instrumental conditioning, the external stimulus that signals a particular relationship between the instrumental response and the reinforcer.

- TH2 cytokines

Cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-3, -4, -5, -6, -10 and -12 secreted by TH2 helper T lymphocytes to control various aspects of the antibody response.

- Bioavailability

The fraction or percentage of an administered drug or other substance that becomes available to the target tissue after administration.

- Somnogenic

Sleep-inducing

Footnotes

Competing interests statement The authors declare no competing financial interests.

DATABASES

The following terms in this article are linked online to: Entrez Gene: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query. fcgi?db=gene A1AR | A2AAR | A2BAR | A3AR | CD39 | CD73 | IL-2 | IL-4 | IL-13

OMIM: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db=OMIM Huntington’s disease | Parkinson’s disease Access to this interactive links box is free online.

References

- 1.Fredholm BB, IJzerman AP, Jacobson KA, Klotz KN, Linden J. International Union of Pharmacology. XXV. Nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors. Pharmacol. Rev. 2001;53:527–552. A publication on AR nomenclature, structure, function and regulation by members of NC-IUPHAR subcommittee.

- 2.Linden J. Adenosine in tissue protection and tissue regeneration. Mol. Pharmacol. 2005;67:1385–1387. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.011783. Summarizes four modes of adenosine’s tissue protective action.

- 3.McGaraughty S, Cowart M, Jarvis MF, Berman RF. Anticonvulsant and antinociceptive actions of novel adenosine kinase inhibitors. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2005;5:43–58. doi: 10.2174/1568026053386845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zimmermann H. Extracellular metabolism of ATP and other nucleotides. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2000;362:299–309. doi: 10.1007/s002100000309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pascual O, et al. Astrocytic purinergic signalling coordinates synaptic networks. Science. 2005;310:113–116. doi: 10.1126/science.1116916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parkinson FE, Xiong W, Zamzow CR. Astrocytes and neurons: different roles in regulating adenosine levels. Neurol. Res. 2005;27:153–160. doi: 10.1179/016164105X21878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao ZG, Kim SK, IJzerman AP, Jacobson KA. Allosteric modulation of the adenosine family of receptors. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2005;5:545–553. doi: 10.2174/1389557054023242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Calker D, Muller M, Hamprecht B. Adenosine regulates via two different types of receptors, the accumulation of cyclic AMP in cultured brain cells. J. Neurochem. 1979;33:999–1005. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1979.tb05236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Londos C, Cooper DM, Wolff J. Subclasses of external adenosine receptors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1980;77:2551–2554. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.5.2551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tawfik HE, Schnermann J, Oldenburg PJ, Mustafa SJ. Role of A1 adenosine receptors in the regulation of vascular tone. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2005;288:H1411–H1416. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00684.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rogel A, Bromberg Y, Sperling O, Zoref-Shani E. Phospholipase C is involved in the adenosine-activated signal transduction pathway conferring protection against iodoacetic acid-induced injury in primary rat neuronal cultures. Neurosci. Lett. 2005;373:218–221. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Belardinelli L, Shryock JC, Song Y, Wang D, Srinivas M. Ionic basis of the electrophysiological actions of adenosine on cardiomyocytes. FASEB J. 1995;9:359–365. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.9.5.7896004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reid EA, et al. In vivo adenosine receptor preconditioning reduces myocardial infarct size via subcellular ERK signalling. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2005;288:H2253–H2259. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01009.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kull B, Svenningsson P, Fredholm BB. Adenosine A2A receptors are colocalized with and activate Golf in rat striatum. Mol. Pharmacol. 2000;58:771–777. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.4.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fresco P, Diniz C, Goncalves J. Facilitation of noradrenaline release by activation of adenosine A2A receptors triggers both phospholipase C and adenylate cyclase pathways in rat tail artery. Cardiovasc. Res. 2004;63:739–746. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Offermanns S, Simon MI. Gα15 and Gα16 couple a wide variety of receptors to phospholipase C. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:15175–15180. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.25.15175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daly JW, Butts-Lamb P, Padgett W. Subclasses of adenosine receptors in the central nervous system: interaction with caffeine and related methylxanthines. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 1983;3:69–80. doi: 10.1007/BF00734999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brackett LE, Daly JW. Functional characterization of the A2B adenosine receptor in NIH 3T3 fibroblasts. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1994;47:801–814. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(94)90480-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peakman MC, Hill SJ. Adenosine A2B-receptor-mediated cyclic AMP accumulation in primary rat astrocytes. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1994;111:191–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb14043.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feoktistov I, Biaggioni I. Adenosine A2B receptors evoke interleukin-8 secretion in human mast cells. An enprofylline-sensitive mechanism with implications for asthma. J. Clin. Invest. 1995;96:1979–1986. doi: 10.1172/JCI118245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gao Z, Chen T, Weber MJ, Linden J. A2B adenosine and P2Y2 receptors stimulate mitogen-activated protein kinase in human embryonic kidney-293 cells. Cross-talk between cyclic AMP and protein kinase C pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:5972–5980. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.9.5972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Linden J, Thai T, Figler H, Jin X, Robeva AS. Characterization of human A2B adenosine receptors: radioligand binding, western blotting, and coupling to Gq in human embryonic kidney 293 cells and HMC-1 mast cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 1999;56:705–713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Donoso MV, Lopez R, Miranda R, Briones R, Huidobro-Toro JP. A2B adenosine receptor mediates human chorionic vasoconstriction and signals through the arachidonic acid cascade. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2005;288:H2439–H2449. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00548.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou QY, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of an adenosine receptor: the A3 adenosine receptor. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:7432–7436. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abbracchio MP, et al. G protein-dependent activation of phospholipase C by adenosine A3 receptors in rat brain. Mol. Pharmacol. 1995;48:1038–1045. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shneyvays V, et al. Role of adenosine A1 and A3 receptors in regulation of cardiomyocyte homeostasis after mitochondrial respiratory chain injury. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2005;288:H2792–H2801. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01157.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Englert M, Quitterer U, Klotz KN. Effector coupling of stably transfected human A3 adenosine receptors in CHO cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2002;64:61–65. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(02)01071-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fossetta J, et al. Pharmacological analysis of calcium responses mediated by the human A3 adenosine receptor in monocyte-derived dendritic cells and recombinant cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 2003;63:342–350. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.2.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shneyvays V, Zinman T, Shainberg A. Analysis of calcium responses mediated by the A3 adenosine receptor in cultured newborn rat cardiac myocytes. Cell Calcium. 2004;36:387–396. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tracey WR, Magee W, Masamune H, Oleynek JJ, Hill RJ. Selective activation of adenosine A3 receptors with N6-(3-chlorobenzyl)-5′-N-methylcarbox-amidoadenosine (CB-MECA) provides cardioprotection via KATP channel activation. Cardiovasc. Res. 1998;40:138–145. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00112-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mozzicato S, Joshi BV, Jacobson KA, Liang BT. Role of direct RhoA-phospholipase D1 interaction in mediating adenosine-induced protection from cardiac ischemia. FASEB J. 2004;18:406–408. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0592fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fishman P, et al. Evidence for involvement of Wnt signalling pathway in IB-MECA mediated suppression of melanoma cells. Oncogene. 2002;21:4060–4064. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schulte G, Fredholm BB. Signalling pathway from the human adenosine A3 receptor expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells to the extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2. Mol. Pharmacol. 2002;62:1137–1146. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.5.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schulte G, Fredholm BB. Signalling from adenosine receptors to mitogen-activated protein kinases. Cell Signal. 2003;15:813–827. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(03)00058-5. Reports that each of the four ARs can activate one or more of the MAPKs by substantially different mechanisms.

- 35.Merighi S, et al. A3 adenosine receptor activation inhibits cell proliferation via phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT-dependent inhibition of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)1/2 phosphorylation in A375 human melanoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:19516–19526. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413772200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Olah ME, Stiles GL. The role of receptor structure in determining adenosine receptor activity. Pharmacol. Ther. 2000;85:55–75. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(99)00051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yan L, Burbiel JC, Maass A, Müller CE. Adenosine receptor agonists: from basic medicinal chemistry to clinical development. Expert Opin. Emerging Drugs. 2003;8:537–576. doi: 10.1517/14728214.8.2.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim SK, et al. Modelling the adenosine receptors: Comparison of binding domains of A2A agonist and antagonist. J. Med. Chem. 2003;46:4847–4859. doi: 10.1021/jm0300431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tchilibon S, et al. (N)-Methanocarba-2,N6-disubstituted adenine nucleosides as highly potent and selective A3 adenosine receptor agonists. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:1745–1758. doi: 10.1021/jm049580r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moro S, Gao ZG, Jacobson KA, Spalluto G. Progress in pursuit of therapeutic adenosine receptor antagonists. Med. Res. Rev. 2006;26:131–159. doi: 10.1002/med.20048. Summary of the most recent progress in developing new therapeutic AR antagonists.

- 41.Moro S, Bacillieri M, Cacciari B, Spalluto G. Autocorrelation of molecular electrostatic potential surface properties combined with partial least squares analysis as new strategy for the prediction of the activity of human A3 adenosine receptor antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:5698–5704. doi: 10.1021/jm0502440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gao ZG, et al. Structural determinants of A3 adenosine receptor activation: Nucleoside ligands at the agonist/antagonist boundary. J. Med. Chem. 2002;45:4471–4484. doi: 10.1021/jm020211+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gao ZG, Blaustein J, Gross AS, Melman N, Jacobson KA. N6–Substituted adenosine derivatives: selectivity, efficacy, and species differences at A3 adenosine receptors, Biochem. Pharmacol. 2003;65:1675–1684. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00153-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martin PL, Wysocki RJ, Jr, Barrett RJ, May JM, Linden J. Characterization of 8-(N-methylisopropyl)amino-N6-(5′-endohydroxy-endonorbornyl)-9-methyladenine (WRC-0571), a highly potent and selective, non-xanthine antagonist of A1 adenosine receptors. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1996;276:490–499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rieger JM, Brown ML, Sullivan GW, Linden J, MacDonald TL. Design, synthesis, and evaluation of novel adenosine A2A receptor agonists. J. Med. Chem. 2001;44:531–539. doi: 10.1021/jm0003642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bridges AJ, et al. N6-[2-(3, 5-dimethoxyphenyl)-2-(2-methylphenyl)ethyl]adenosine and its uronamide derivatives. Novel adenosine agonists with both high affinity and high selectivity for the adenosine A2 receptor. J. Med. Chem. 1988;31:1282–1285. doi: 10.1021/jm00402a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Palmer TM, Poucher SM, Jacobson KA, Stiles GL. 125I-4-(2-[7-Amino-2-{furyl}{1,2,4}triazolo{2,3-a} {1,3,5}triazin-5-ylaminoethyl)phenol (125I-ZM241385), a high affinity antagonist radioligand selective for the A2A adenosine receptor. Mol. Pharmacol. 1996;48:970–974. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baraldi PG, et al. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of a second generation of pyrazolo[4,3-e]1, 2,4-triazolo[1,5-c]pyrimidines as potent and selective A2A adenosine receptor antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 1998;41:2126–2133. doi: 10.1021/jm9708689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ji XD, Jacobson KA. [3H]-ZM241385 as a radioligand at recombinant human A2B adenosine receptors. Drug Des. Discov. 1999;16:217–226. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kase H, et al. Progress in pursuit of therapeutic A2A antagonists: the adenosine A2A receptor selective antagonist KW6002: research and development toward a novel nondopaminergic therapy for Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 2003;61:S97–S100. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000095219.22086.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Volpini R, Costanzi S, Vittori S, Cristalli G, Klotz KN. Medicinal chemistry and pharmacology of A2B adenosine receptors. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2003;3:427–443. doi: 10.2174/1568026033392264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Beukers MW, et al. New, non-adenosine, highpotency agonists for the human adenosine A2B receptor with an improved selectivity profile compared to the reference agonist N-ethylcarboxamido-adenosine. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:3707–3709. doi: 10.1021/jm049947s. The first report of non-nucleoside agonists for the human A2BAR, with one of those compounds showing potency of about 10 nM.

- 53.Ji X, Kim YC, Ahern DG, Linden J, Jacobson KA. [3H]MRS 1754, a selective antagonist radioligand for A2B adenosine receptors. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2001;61:657–663. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00531-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gessi S, et al. Expression, pharmacological profile, and functional coupling of A2B receptors in a recombinant system and in peripheral blood cells using a novel selective antagonist radioligand, [3H]MRE 2029-F20. Mol. Pharmacol. 2005;67:2137–2147. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.009225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stewart M, et al. [3H]OSIP339391, a selective, novel, and high affinity antagonist radioligand for adenosine A2B receptors. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2004;68:305–312. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jacobson KA. A3 adenosine receptors: novel ligands and paradoxical effects. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1998;19:184–191. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(98)01203-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Olah ME, Gallo-Rodriguez C, Jacobson KA, Stiles GL. 125I-4-Aminobenzyl-5′-N-methylcarbox-amidoadenosine, a high affinity radioligand for the rat A3 adenosine receptor. Mol. Pharmacol. 1994;45:978–982. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jeong LS, et al. N6–Substituted D-4′-thioadenosine-5′-methyluronamides: potent and selective agonists at the human A3 adenosine receptor. J. Med. Chem. 2003;46:3775–3777. doi: 10.1021/jm034098e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Linden J. Cloned adenosine A3 receptors: pharmacological properties, species differences and receptor functions. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1994;15:298–306. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(94)90011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yang H, et al. The cross-species A3 adenosine-receptor antagonist MRS 1292 inhibits adenosine-triggered human nonpigmented ciliary epithelial cell fluid release and reduces mouse intraocular pressure. Curr. Eye Res. 2005;30:747–754. doi: 10.1080/02713680590953147. Application of the first rationally designed, cross-species, nucleoside antagonist in an animal model for antiglaucoma effects.

- 61.Müller CE, Diekmann M, Thorand M, Ozola V. [3H]8-Ethyl-4-methyl-2-phenyl-(8R)-4,5,7,8-tetrahydro-1H-imidazo[2,1-i]-purin-5-one ([3H]PSB-11), a novel high-affinity antagonist radioligand for human A3 adenosine receptors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2002;12:501–503. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(01)00785-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Perreira M, et al. ‘Reversine’ and its 2-substituted adenine derivatives as potent and selective A3 adenosine receptor antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:4910–4918. doi: 10.1021/jm050221l. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zablocki JA, Wu L, Shryock J, Belardinelli L. Partial A1 adenosine receptor agonists from a molecular perspective and their potential use as chronic ventricular rate control agents during atrial fibrillation (AF) Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2004;4:839–854. doi: 10.2174/1568026043450998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]