Summary

Cranial dural arteriovenous fistulas (DAVFs) may give rise to myelopathy due to spinal perimedullary venous drainage causing intramedullary venous hypertension. Such cases are uncommon but not rare, with several cases reported in the literature. We report a case of foramen magnum DAVF presenting with symptoms of tetraparesis. The unusual feature was that in this case it was due to compression of the cervicomedullary junction by a large venous pouch rather than the result of spinal perimedullary venous hypertension. Transarterial glue embolization achieved good reduction of flow in the fistula with shrinkage of the venous pouch and corresponding clinical improvement.

Key words: dural arteriovenous fistula, foramen magnum, tetraparesis, venous pouch

Introduction

We report a case of intracranial dural arteriovenous fistula presenting with tetraparesis due to compression of the cervicomedullary junction by a large venous pouch.

Case Report

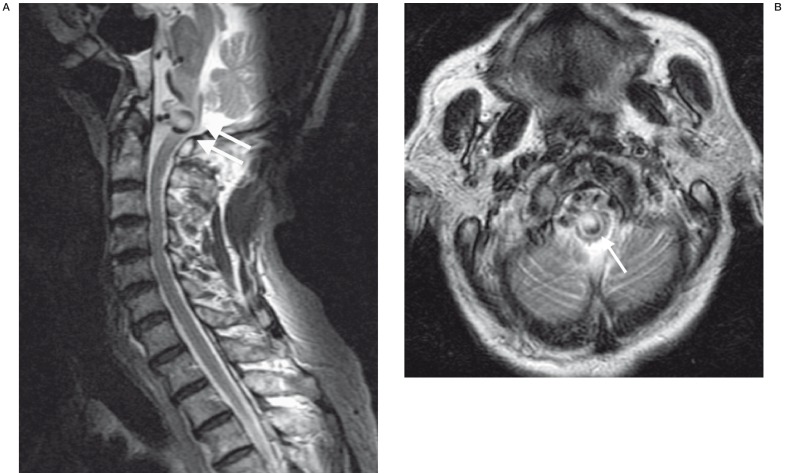

The patient, a 67-year-old Chinese man, presented with generalised limb weakness and neck pain for three days. He had a history of hypertension and was in heart failure secondary to dilated cardiomyopathy. He was on warfarin anti-coagulation therapy because of dilated cardiomyopathy and atrial fibrillation. On examination, he had decreased power in all four limbs with movement against gravity only. He had no associated bladder or bowel symptoms. Non-contrast axial computed tomography (CT) of the brain was performed which showed chronic lacunar infarcts in the left hemipons, left thalamus and left lentiform nucleus. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the cervical spine was obtained in view of the tetraparesis. This showed changes of cervical spondylosis and mild spinal canal stenosis at C4-5 level with no significant cord compression. There was no evidence of abnormal signal within the cervical cord parenchyma. There was, however, a 10 mm vascular pouch compressing the ventral aspect of the cervicomedullary junction (figure 1A,B).

Figure 1.

A) MRI sagittal T2-weighted image of the cervical spine shows large venous pouch (double arrows) compressing the cervico-medullary junction and B) MRI axial T2-weighted image at the level of the medulla again shows compression of the medulla by the large venous pouch (arrow).

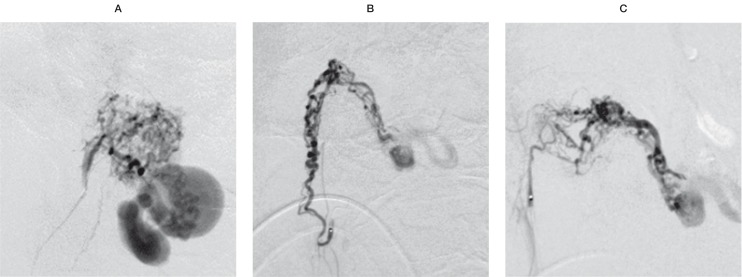

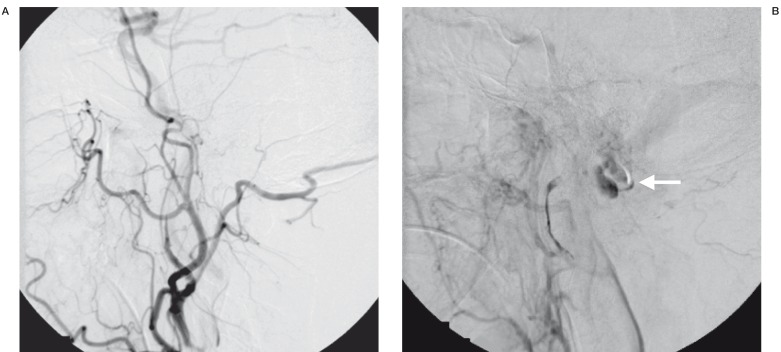

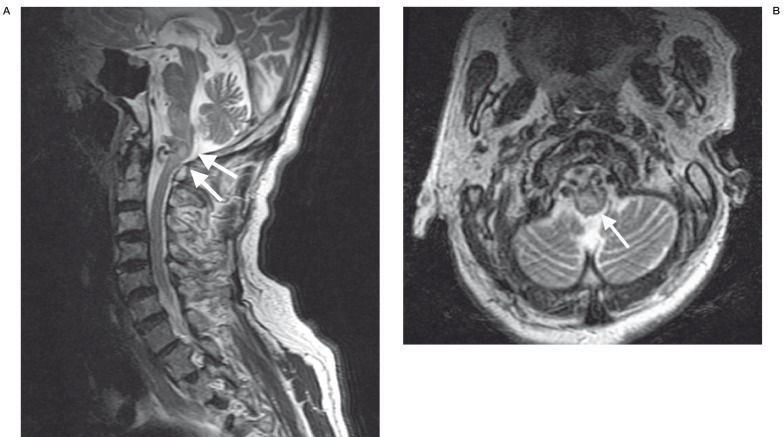

This vascular pouch led towards a venous structure in the pre-pontine cistern, which drained upwards in the direction of the left perimesencephalic cistern. Features raised suspicion of an arteriovenous fistula at the level of the foramen magnum. No abnormal flow voids were detected around the cervical spinal cord. Digital subtraction cerebral angiography was performed after normalisation of the coagulation profile. The angiography showed an arteriovenous fistula at the craniocervical junction, which derived its supply mainly from the right ascending pharyngeal artery. The fistula led into the large venous pouch which was shown on MRI. This eventually drained upwards and backwards into the straight sinus (figure 2A,B). There was a small supply from the right occipital artery. Much smaller feeders were also noted from the meningeal branches of the right vertebral artery as well as the right posterior auricular artery. Embolization of the fistula was carried out using cyanoacrylate (NBCA). A guiding catheter was placed in the right external carotid artery. A microcatheter was introduced into the largest feeder arising from the neuromeningeal branch of the right ascending pharyngeal artery. Embolization of this feeding pedicle was carried out with NBCA. Selective cannulation of the two other major feeders arising from the right ascending pharyngeal and right occipital arteries was then carried out, followed by occlusion of these two feeders with NBC A (figure 3A,B,C). The very small feeders arising from the right vertebral and right posterior auricular arteries were not embolized. Post embolization angiogram showed a marked reduction of flow through the arteriovenous fistula with considerable stasis in the venous pouch (figure 4A,B). Follow up MRI at two days post embolization showed thrombosis and some shrinkage of the venous pouch with decreased mass effect on the medulla oblongata (figure 5A,B). The patient was re-started on warfarin at two weeks post embolization. The patient made gradual recovery post treatment. With physiotherapy, the power in the upper limbs returned to full bilaterally. Power in the lower limbs also showed considerable improvement. The patient, however, died two months later from cardiac complications unrelated to the dural arteriovenous fistula.

Figure 2.

Right external carotid angiogram A) arterial phase and B) late phase centred higher, shows the arteriovenous fistula at the level of foramen magnum with large venous pouch (arrow) and venous drainage finally into the straight sinus (double arrow).

Figure 3.

Selective angiography before glue embolization, demonstrating the main feeding pedicles from A) neuro-meningeal branch of the right ascending pharyngeal artery, B) another branch of the right ascending pharyngeal artery, C) branch of the right occipital artery.

Figure 4.

Post embolization control angiogram A) arterial phase showing marked reduction of flow through the fistula and B) late venous phase showing stasis in the venous pouch (arrow).

Figure 5.

MRI at two days post embolization shows: A) thrombosis and some shrinkage of the venous pouch (double arrow) and (B) some relief of compression on the medulla (arrow), compared with pre-treatment images obtained at the same level (figure 1A,B).

Discussion

Cranial dural arteriovenous fistulas (DAVFs) represent 10-15% of all intracranial arteriovenous lesions.1 DAVFs consist of one or more direct arteriovenous connections within the dura mater. It is generally accepted that DAVFs in adults are acquired, as opposed to the pial arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) that are thought to be congenital.

DAVFs can be found anywhere along the dura mater, both cranial and spinal. Spinal DAVFs generally present with a chronic progressive myelopathy caused by venous hypertension in the peri-medullary venous plexus. By contrast, cranial DAVFs may present with a diverse spectrum of clinical signs and symptoms. This may be related to the fistula itself (eg, bruit) or the venous hypertension in the involved venous territory. In the brain, both haemorrhagic and non-haemorrhagic neurologic deficit can occur. The clinical presentation is very much related to the pattern of venous drainage, the territory of the draining veins and the presence of cortical venous drainage (CVR), with CVR carrying a high risk of intradural bleeding 2.

Cranial DAVFs are generally classified into "benign" and "aggressive", which apply to the symptomatology and natural history of the lesions 3,4. Headache, pulsatile bruit and orbital symptoms including cranial nerve deficits are examples of symptoms caused by benign lesions. Both non-haemorrhagic and haemorrhagic neurologic deficits are considered aggressive. The presence of CVR, venous ectasia and galenic drainage are risk factors for an aggressive course. DAVFs may also be classified by the location of the fistula. The fistula site may be epidural (osteodural shunts), dural (dural sinus shunts) or subdural (in the subdural or subarachnoid space).

In our patient, the arteriovenous shunt was at the level of the foramen magnum. Venous drainage was not direct into one of the dural sinuses. Instead, the draining vein was shown on MRI to run alongside the basilar artery in the prepontine cistern and around the ambient cistern, finally towards the straight sinus. Angiography showed the major dural sinuses to be patent with no evidence of cortical venous reflux. The shunt may therefore represent a dural-subdural shunt. The unusual feature was the clinical presentation of tetraparesis, due to cervicomedullary junction compression by the large venous pouch at the level of the shunt. DAVFs causing myelopathy are uncommon but not rare. Review of the literature reveals several case reports of cranial DAVFs, including DAVFs at the craniocervical junction, presenting with myelopathy 5-14. The myelopathy is usually due to spinal medullary venous drainage giving rise to intramedullary venous hypertension in the cord, similar to the pathophysiology in spinal DAVFs. In our patient, however, angiography showed no evidence of venous drainage into the spinal perimedullary venous plexus. There was also no evidence of spinal cord oedema on MRI to suggest intramedullary venous hypertension. Tetraparesis in our patient was due to severe compression on the cervicomedullary junction by the large venous pouch.

Based on the natural history of DAVFs (benign versus aggressive lesions), the indications for treatment in the two types of lesions differ. Benign lesions generally follow a benign course. Treatment in such cases is usually indicated for severe debilitating symptoms whereas the majority of benign lesions may be managed conservatively and followed clinically. Aggressive lesions, on the other hand, have been shown to be associated with significant annual morbidity and mortality hence treatment is usually mandatory at presentation 3,4. Treatment in our patient was carried out due to the presence of neurologic deficit from cervicomedullary compression. The transarterial route was chosen. A transvenous route would have been difficult and less appropriate in this case where the fistula did not drain direct into one of the major dural sinuses. Superselective cannulation of the main arterial feeders was carried out followed by embolization using NBCA as the embolic agent. This resulted in marked reduction of flow in the DAVF with stasis in the venous pouch seen on the post embolization control angiogram. The symptoms improved following endovascular therapy, with shrinkage of the venous pouch and relief of compression on the cervicomedullary junction shown on MRI obtained two days post embolization.

Conclusions

Cranial DAVFs may give rise to myelopathy due to spinal perimedullary venous drainage causing intramedullary venous hypertension. Such cases are uncommon but not rare, with several case reports in the literature. Our patient with a foramen magnum DAVF supplied by branches of the external carotid artery also presented with symptoms of tetraparesis. The unusual feature was that in this case, it was due to compression of the cervicomedullary junction by a large venous pouch rather than the result of spinal perimedullary venous hypertension. Transarterial glue embolization achieved a good reduction of flow in the fistula with shrinkage of the venous pouch and corresponding clinical improvement.

References

- 1.Van Dijk JM, Willinsky RA. Venous congestive encephalopathy related to cranial dural arteriovenous fistulas. Neuroimag Clin N Am. 2003;13:55–72. doi: 10.1016/s1052-5149(02)00063-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lasjaunias P, Chiu M, terBrugge K, et al. Neurological manifestations of intracranial dural arteriovenous malformations. J Neurosurg. 1986;64:724–30. doi: 10.3171/jns.1986.64.5.0724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davies MA, Saleh J, terBrugge K, et al. The natural history and management of intracranial dural arteriovenous fistula. Part 1. Benign lesions. Interventional Neuroradiology. 1997;3:295–302. doi: 10.1177/159101999700300404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies MA, terBrugge K, Willinsky RA, et al. The natural history and management of intracranial dural arteriovenous fistula. Part 2. Aggressive lesions. Interventional Neuroradiology. 1997;3:303–11. doi: 10.1177/159101999700300405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalamangalam GP, Bhattacharya J, et al. Myelopathy from intracranial dural arteriovenous fistula. J Neurol, Neurosurg & Psychiatry. 2002;72(6):816–818. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.72.6.816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wiesmann M, Padovan CS, et al. Intracranial dural arteriovenous fistula with spinal medullary venous drainage. Eur Radiol. 2000;10(10):1606–1609. doi: 10.1007/s003300000382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoshida S, Oda Y, et al. Progressive myelopathy caused by dural arteriovenous fistula at the craniocervical junction-case report. Neurologia Medico-Chirurgica. 1999;39(5):376–379. doi: 10.2176/nmc.39.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oishi H, Okuda O, et al. Successful surgical treatment of a dural arteriovenous fistula at the craniocervical junction with reference to pre- and postoperative MRI. Neuroradiology. 1999;41(6):463–467. doi: 10.1007/s002340050785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hahnel S, Jansen O, Geletneky K. MR appearance of an intracranial dural arteriovenous fistula leading to cervical myelopathy. Neurology. 1998;51(4):1131–1135. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.4.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ernst RJ, Gaskill-Shipley M, et al. Cervical myelopathy associated with intracranial dural arteriovenous fistula: MR findings before and after treatment. Am J Neuroradiol. 1997;18(7):1330–1334. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mascalchi M, Scazzeri F, et al. Dural arteriovenous fistula at the craniocervical junction with perimedullary venous drainage. Am J Neuroradiol. 1996;17(6):1137–1141. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deopujari CE, Dadachanji MC, Singhal BS. Cervical myelopathy caused by an intracranial dural arteriovenous fistula. British J Neurosurg. 1995;9(5):671–674. doi: 10.1080/02688699550040963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bret P, Salzmann M, et al. Dural arteriovenous fistula of the posterior fossa draining into the spinal medullary veinsan unusual cause of myelopathy: case report. Neurosurgery. 1994;35(5):965–968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Versari PP, D'Aliberti G, et al. Progressive myelopathy caused by intracranial dural arteriovenous fistula: report of two cases and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 1993;33(5):914–918. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199311000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]