Background: Tumor necrosis factor α-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) resistance in leukemia is not fully understood.

Results: shRNA-targeted knockdown of WT1 oncogene sensitizes TRAIL-resistant leukemia cells to TRAIL-induced cell death.

Conclusion: WT1 expression mediates TRAIL resistance in leukemia cells by inducing antiapoptotic protein Bcl-xL.

Significance: Approaches to silence WT1 expression can be exploited to overcome TRAIL resistance in myeloid leukemias.

Keywords: Apoptosis, Cancer, Drug Resistance, Leukemia, shRNA, TRAIL Resistance, WT1

Abstract

Tumor necrosis factor α-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) is considered a promising cancer therapeutic agent due to its ability to induce apoptosis in a variety of cancer cells, while sparing normal cells. However, many human tumors including acute myeloid leukemia (AML) are partially or completely resistant to monotherapy with TRAIL, limiting its therapeutic utility. Therefore, identification of factors that contribute to TRAIL resistance may facilitate future development of more effective TRAIL-based cancer therapies. Here, we report a previously unknown role for WT1 in mediating TRAIL resistance in leukemia. Knockdown of WT1 with shRNA rendered TRAIL-resistant myeloid leukemia cells sensitive to TRAIL-induced cell death, and re-expression of shRNA-resistant WT1 restored TRAIL resistance. Notably, TRAIL-mediated apoptosis in WT1-silenced cells was largely due to down-regulation of the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-xL. Moreover, WT1 expression strongly correlated with overexpression of Bcl-xL in AML cell lines and blasts from AML patients. Furthermore, we found that WT1 transactivates Bcl-xL by directly binding to its promoter. We previously showed that WT1 is a novel client protein of heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90). Consistent with this, pharmacological inhibition of Hsp90 resulted in reduced WT1 and Bcl-xL expression leading to increased sensitivity of leukemia cells to TRAIL-mediated apoptosis. Collectively, our results suggest that WT1-dependent Bcl-xL overexpression contributes to TRAIL resistance in myeloid leukemias.

Introduction

Chemotherapy has improved the outcome for leukemia patients, but it often results in highly debilitating side effects due to considerable toxicity toward normal tissues. TRAIL2 is a promising cancer therapy that preferentially induces apoptosis in cancer cells without exhibiting adverse effects on normal cells (1, 2). TRAIL induces apoptosis through binding its two proapoptotic receptors, DR4 (TRAIL-R1) and DR5 (TRAIL-R2), followed by recruitment of an adaptor molecule (Fas-associated death domain) and initiator caspases (caspase-8/10) to the death-inducing signaling complex and subsequent activation of downstream effector caspases (3). The apoptotic signals at the death receptors can cross-talk with the mitochondrial pathway through the caspase-8 cleavage of Bid. The truncated Bid translocates to mitochondria, triggers cytochrome c release, and amplifies the apoptotic signal (4). Overexpression of the antiapoptotic molecules such as Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL can block cytochrome c release and subsequent caspase activation in response to a variety of apoptotic stimuli (5). Based on several promising preclinical studies, recombinant human TRAIL and agonistic anti-TRAIL receptor DR4 and DR5 antibodies have recently entered clinical trials (6). However, many tumors including acute myeloid leukemia (AML) are resistant to the proapoptotic effects of TRAIL (7, 8). Several possible mechanisms of TRAIL resistance have been outlined, including low expression of death receptors DR4 and DR5, overexpression of decoy receptors DcR1 and DcR2, and elevated levels of negative regulators of apoptosis (9–12). In the present study, we have investigated the role of WT1 in TRAIL resistance in myeloid leukemia cells and have explored the underlying mechanisms.

WT1 was originally identified as a tumor suppressor gene (13); however, increasing evidence suggests that WT1 plays an oncogenic role in leukemia and other tumors (14, 15). WT1 is a zinc finger transcription factor that can either activate or repress genes involved in growth, apoptosis, and differentiation (16–19). WT1 has been shown to be highly expressed in several solid tumors and hematopoietic neoplasms including AML (20, 21), and its overexpression has been associated with poor clinical outcome (22, 23). Numerous studies have established WT1 as a reliable marker for minimal residual disease assessment in acute leukemia patients (24–26). We and others have shown that forced expression of WT1 promoted cell growth and that suppression of WT1 expression led to growth inhibition in leukemia cells in vitro and in vivo (27, 28). In the present study, we demonstrate, for the first time, that silencing of WT1 expression potentiated TRAIL-induced apoptosis in myeloid leukemia cells through down-regulation of the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-xL.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Antibodies, Chemicals, Cell Culture, and Patient Samples

The mouse monoclonal anti-WT1 and anti-β-actin antibodies were obtained from Millipore and Sigma, respectively. All other antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technologies. HeLa and human myeloid leukemia cell lines K562, THP-1, and MV4-11 were purchased from ATCC and grown in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin mixtures (Invitrogen) antibiotics. K562 cells with stable WT1 knockdown has been described previously (27). Peripheral blood mononuclear blasts were isolated by Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient from deidentified AML patient samples obtained from the Institution Review Board-approved biorepository at the Texas Transplant Institute.

Plasmids and Constructs

The control and Bcl-xL shRNA vectors (Open Biosystems), and the plasmid harboring full-length Bcl-xL cDNA were received as a kind gift from Dr. Salvatore Oliviero (29). The full-length Bcl-xL cDNA was PCR-amplified using the primer pair 5′-AACGAATTCGACCATGTCTCAGAGCAACCGGGAG-3′ and 5′-CCGCTCGAGTCATTTCCGACTGAAGAGTGAG-3′). The PCR product was cloned via EcoRI/XhoI sites into pcDNA3.1 (+) vector. The human Bcl-xL promoter-reporter construct (Bcl-xL-Luc) was generated by amplifying the promoter sequence (from nucleotides −635 to +15 relative to transcription start site) from K562 cell genomic DNA and cloned into SacI/HindIII sites of promoterless pGL3-Basic luciferase vector (Promega). All constructs were verified by DNA sequencing.

Transient Transfection and Western Blot Analysis

HeLa cells were transfected with the appropriate plasmids for 24 h using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Western blotting of whole cell protein extracts from cells and AML blasts was performed as described previously (27).

Luciferase Reporter Assay

HeLa cells were plated in 24-well plates at a density of 25,000 cells/well and transiently co-transfected with a constant amount of a Bcl-xL promoter luciferase reporter (Bcl-xL-Luc;100 ng) and Renilla luciferase expression plasmid (pRL-TK; 10 ng) together with or without the WT1 expression plasmid (250 ng) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). For all transfections, the total DNA amounts were kept constant (500 ng) using empty parental plasmid (pcDNA 3.1). Luciferase activity was determined 48 h after transfection using the Dual-Luciferase reporter assay kit (Promega). Results represent an average firefly luciferase value after normalization to Renilla luciferase signal, and the -fold activation was obtained by setting the value of control as 1.0. All transfections were carried out in triplicate.

Measurement of Apoptosis

Apoptosis was measured using the annexin V-FITC apoptosis detection kit (BioVision) in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol with a FACScan flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and CellQuest software.

Design of shRNA-resistant WT1 cDNA and Rescue Experiments

The shRNA-resistant WT1 (WT1SR) expression construct was generated by introducing four silent mutations into the cDNA sequence that is targeted by WT1 shRNA without changing the amino acid sequence. All mutagenesis was performed using the QuikChange II XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies). The resulting WT1 cDNA was sequenced to verify the presence of silent mutations and subcloned into pcDNA3.1 vector. For WT1 rescue experiments, WT1 knockdown K562 cells were transfected with control (vector) or WT1SR plasmid, and stable cells with WT1 overexpression were generated by G418 sulfate selection.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Assay

ChIP assays were performed using the HighCell# ChIP kit (Diagenode) as per the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, K562 cells were cross-linked by formaldehyde to a final concentration of 1%, and cross-linking was stopped by adding glycine to a final concentration of 125 mm. After cross-linking, the chromatin DNA was sheared into 200–500-bp fragments by sonication using a Bioruptor (Diagenode). The sheared chromatin was incubated with WT1 rabbit polyclonal antibody (C-19; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or rabbit IgG (as a negative control) at 4 °C overnight. The immunocomplexes were precipitated with protein-A magnetic beads. After reversing the cross-link, the purified DNA was used as template for 40 cycles of PCR amplification with 5′-GCCAAGGGGCGTGCAAGAGA-3′ and 5′-GAGGGATGCGACGACCCGGC-3′ primer set. The amplified PCR fragments were analyzed on 2% agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

RNA Isolation and Semiquantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated using the Absolutely RNA miniprep kit (Agilent Technologies). One microgram of total RNA was reverse-transcribed using the SuperScript III first-strand synthesis system (Invitrogen). Semiquantitative PCR was performed using AccuPrime Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen) and 30 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 60 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s. β-Actin was used as an internal control for gene expression. The following gene-specific primers were used for PCR: Bcl-xL, 5′-ATGGCAGCAGTAAAGCAAGCG-3′ and 5′-TCATTTCCGACTGAAGAGTGA-3′; WT1, 5′-TGACACTGGCAAAACAATGCA-3′ and 5′-GGTCCTTTTCACCAGCAAGCT-3′; and β-actin, 5′-AGCGAGCATCCCCCAAAGTT-3′ and 5′-GGGCACGAAGGCTCATCATT-3′. The PCR products were resolved by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis.

Statistical Analysis

The results are representative of at least three independent experiments and are presented as the means ± S.D. of triplicate samples. Data were analyzed using the Student's t test and analysis of variance with the Tukey's multiple comparison test. Differences are considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

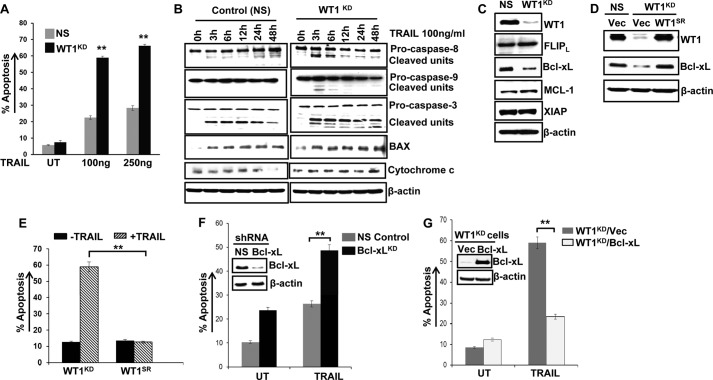

WT1 Knockdown Sensitizes Leukemia Cells to TRAIL

Resistance to TRAIL-induced apoptosis has been reported to be associated with overexpression of antiapoptotic proteins (30). Therefore, we examined whether WT1, which is frequently overexpressed in leukemia cells, is associated with TRAIL resistance. Human myeloid leukemia K562 cells are resistant to TRAIL (31), and shRNA-mediated silencing of WT1 expression in these cells significantly enhanced TRAIL-induced apoptosis when compared with cells transfected with nonsilencing (NS) shRNA (Fig. 1A). To confirm that TRAIL-induced cell death in WT1-depleted cells occurs through an apoptotic pathway, we evaluated the effects of WT1 knockdown and TRAIL on several molecules involved in apoptosis. As shown in Fig. 1B, co-treatment with TRAIL and WT1 shRNA elicited the activation of initiator caspase-8/-9 and effector caspase-3 and also induced Bax expression, consistent with induction of apoptosis (Fig. 1B). Bax promotes apoptosis by inducing mitochondrial release of cytochrome c, which in turn facilitates caspase activation via apoptosome (32). Consistent with this, more cytochrome c release was observed after TRAIL treatment in WT1 knockdown (WT1KD) cells than in control cells (Fig. 1B). Because TRAIL resistance in cancers has been attributed to attenuated expression of the TRAIL death receptors DR4 and DR5 or overexpression of the decoy receptors DcR1 and DcR2 (11), we examined the expression of these receptors in WT1-depleted cells. Interestingly, WT1 knockdown cells did not display significant differences in the expression of DRs and DcRs as assessed by Western blotting (data not shown). Thus, our data suggest that WT1 does not regulate death-inducing signaling complex by modulating the expression levels of TRAIL receptors.

FIGURE 1.

Silencing WT1 expression enhances the sensitivity of leukemia cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis. A, K562 cells stably transfected with NS or WT1 shRNA to silence WT1 expression were described previously (26). Control (NS) or WT1 knockdown (WT1KD) K562 cells were untreated (UT) or treated with the indicated TRAIL concentrations for 48 h, and apoptosis was assessed by the annexin V/PI staining method. Data represent means ± S.D. of triplicates (**, p < 0.005). B, K562 control or WT1KD cells were treated with TRAIL for different time points (0–48 h), and protein extracts were subjected to Western blot analysis with the indicated antibodies. The β-actin was used as loading control. C, Western blotting of various antiapoptotic molecules in control (NS) and WT1KD K562 cells. XIAP, X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein. FLIPL, FLICE-inhibitory protein. D, K562 control (NS) and WT1KD cells were transfected with either vector (Vec) or shRNA-resistant WT1 cDNA (WT1SR) by Amaxa Nucleofector and analyzed for WT1 and Bcl-xL protein expression by Western blotting. E, the ectopic expression of WT1SR restored the TRAIL resistance in TRAIL-sensitive WT1KD cells as assessed by annexin V/PI staining. Data represent means ± S.D. of triplicates (**, p < 0.005). F, K562 cells were nucleofected with control (NS) and Bcl-xL shRNA, and cell lysates from puromycin (2 μg/ml)-resistant transfectants were analyzed for Bcl-xL knockdown by Western blotting (inset). Control and Bcl-xL knockdown cells were treated with TRAIL (100 ng/ml), and after 48 h, cells were analyzed for apoptosis as described above. Bcl-xL knockdown enhanced TRAIL-induced apoptosis. UT, untreated. G, WT1KD K562 cells were nucleofected with empty vector (Vec) or Bcl-xL cDNA expression vector and stable G418 (1 mg/ml)-resistant transfectants were analyzed for Bcl-xL overexpression by Western blotting (inset). WT1KD/vector and Bcl-xL overexpression cells were treated with TRAIL (100 ng/ml; 48 h) and analyzed for apoptosis as described above. Overexpression of Bcl-xL prevented TRAIL-mediated sensitization in WT1-depleted K562 cells. Data represent means ± S.D. of triplicates.

The Increased Sensitivity of WT1-depleted Cells to TRAIL Involves Bcl-xL Down-regulation

To further investigate the underlying mechanism of increased susceptibility of WT1KD cells to TRAIL, the expression of various antiapoptotic molecules that interfere with TRAIL signaling was also examined. As shown in Fig. 1C, WT1 down-regulation did not affect expression of FLICE-inhibitory protein (FLIPL), Mcl-1, and X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP). In contrast, the protein levels of Bcl-xL were remarkably reduced by shRNA-mediated suppression of WT1. Because the overexpression of Bcl-xL has been implicated in TRAIL resistance (12, 33), our data suggest that WT1 knockdown induced a decrease of Bcl-xL expression, thus predisposing leukemia cells to apoptosis-inducing effects of TRAIL. In addition, the induction of Bax and down-regulation of Bcl-xL in WT1 knockdown cells thus presumably increased the Bax/Bcl-xL ratio, which, in turn resulted in activation of caspase-3 and -9 and potentiation of TRAIL-mediated apoptosis. These findings are consistent with the earlier reports that the ratio of Bax/Bcl-xL is considered critical for apoptosis induction (34, 35). To eliminate the possibility that results obtained by WT1 knockdown were due to RNAi-mediated off-target effects, we generated an shRNA-resistant WT1 cDNA (WT1SR) and performed rescue experiments. The ectopic expression of WT1SR restored Bcl-xL expression (Fig. 1D) and reversed the TRAIL-sensitizing effect of shRNA-induced WT1 knockdown (Fig. 1E). These findings confirmed that the observed WT1 shRNA-induced sensitization of leukemia cells to TRAIL was caused by specific suppression of WT1 rather than by unforeseen effects of the WT1 shRNA on other genes. Next, we investigated the involvement of Bcl-xL in mediating TRAIL resistance. We found that knockdown of Bcl-xL by shRNA enhanced TRAIL-induced apoptosis (Fig. 1F) and phenocopied the effects of WT1 knockdown in K562 cells. To directly assess the functional contribution of Bcl-xL in WT1-mediated TRAIL resistance, we examined whether ectopic expression of Bcl-xL in WT1-depleted cells restores TRAIL resistance. Interestingly, exogenous Bcl-xL could rescue cells from undergoing TRAIL-induced apoptosis (Fig. 1G). These results demonstrate that Bcl-xL is a key downstream mediator contributing to WT1-dependent TRAIL resistance. Bcl-xL has been reported to act downstream of caspase-8 activation, and Bcl-xL has been shown to prevent Fas- and TNFα-induced apoptosis by inhibiting downstream caspase activation (36, 37). We also observed that overexpression of Bcl-xL protected WT1 knockdown cells against TRAIL by blocking the activation of caspase-9 and caspase-3 (data not shown). These observations are in agreement with previous reports demonstrating that Bcl-xL promotes TRAIL resistance through inhibition of both intrinsic and extrinsic apoptosis pathways (38, 39).

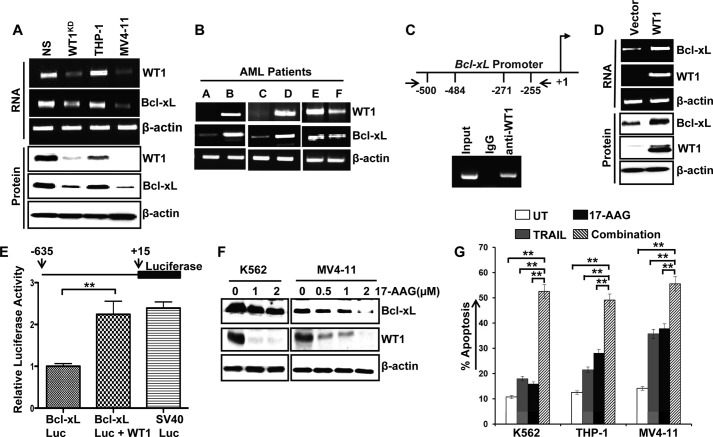

High Expression Levels of WT1 Correlate with Bcl-xL Expression and TRAIL-resistant Leukemia Cell Lines

Next, we analyzed whether myeloid leukemia cells show varied susceptibility to TRAIL and whether WT1 levels correlate with TRAIL sensitivity. Indeed, we found that the levels of WT1 were comparatively lower in MV4-11 cells than in THP-1 and K562 cells (Fig. 2A), and this was associated with differences in TRAIL sensitivity (Fig. 2G; untreated versus TRAIL bars). Interestingly, we found a positive correlation between the levels of WT1 and Bcl-xL transcripts and proteins in myeloid leukemia cell lines (Fig. 2A) and leukemic blasts of AML patients (Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 2.

Correlative expression of WT1 and Bcl-xL in AML cell lines and leukemia blasts was measured; WT1 binds to Bcl-xL promoter and regulates its expression. A, K562 control (NS), WT1KD, and myeloid leukemia cells including THP-1 and MV4-11 were subjected to RNA and protein extraction. The expression of WT1 and Bcl-xL mRNA was analyzed by RT-PCR (upper panel), and protein levels were assessed by Western blotting (lower panel). B, expression of WT1 and Bcl-xL mRNA in leukemia blasts from AML patients was measured by RT-PCR. C, upper panel, schematic diagram of putative WT1 binding sites relative to the transcription start site (+1) in Bcl-xL gene promoter. Lower panel, K562 cells were subjected to ChIP assay with rabbit IgG or anti-WT1 antibody, and precipitated chromatin was used for PCR amplification with primers flanking the WT1 binding site. One-tenth of the volume of chromatin before immunoprecipitation was used for PCR as input. D, HeLa cells were transiently transfected with either empty vector or WT1 expression plasmid, the WT1 and Bcl-xL mRNA levels were measured by RT-PCR, and protein levels were analyzed by Western blotting. E, upper panel, a schematic drawing of the luciferase reporter construct containing Bcl-xL promoter (Bcl-xL-Luc) sequence is shown. For luciferase reporter assay, HeLa cells were transfected as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The luciferase activities were measured by the Dual-Luciferase reporter system (Promega). Lower panel, graph represents means of three experiments ± S.D. F, K562 and MV4-11 cells were treated with the Hsp90 inhibitor, 17-AAG, for 24 h. The protein extracts were subjected to Western blotting for WT1 and Bcl-xL expression. G, K562, THP-1, and MV4-11 cells were left untreated (UT) or treated with either TRAIL (100 ng/ml) or 17-AAG (3 μm) alone or in combination for 48 h, and apoptosis was measured by annexin V/PI staining. Data represent means ± S.D. of triplicates (**, p < 0.005).

WT1 Binds to Bcl-xL Promoter and Positively Regulates Its Expression

The above experiments suggest that WT1 might be a positive regulator of Bcl-xL and prompted us to examine possible WT1 binding sites in Bcl-xL gene promoter. Our in silico analysis using Genomatix MatInspector software identified two potential WT1 binding sites on Bcl-xL promoter. To evaluate whether endogenous WT1 can bind within a chromatin environment to the Bcl-xL promoter region containing the in silico identified putative binding sites, we performed ChIP assays in K562 cells, which express significant amounts of endogenous WT1 and Bcl-xL. WT1 occupancy of the Bcl-xL promoter was detectable in anti-WT1 and not in control IgG precipitates (Fig. 2C). To assess whether forced expression of WT1 could alter the endogenous levels of Bcl-xL, HeLa cells were transiently transfected with empty or WT1 expression vector. The expression of Bcl-xL and WT1 was evaluated by semiquantitative RT-PCR and Western blot analyses. We observed a significant increase in Bcl-xL mRNA and protein levels in WT1-transfected cells when compared with cells transfected with empty vector (Fig. 2D). To address whether the Bcl-xL promoter could respond to WT1, we generated a luciferase reporter construct Bcl-xL-Luc. HeLa cells were transiently transfected with Bcl-xL-Luc together with or without the expression plasmid for WT1. As shown in Fig. 2E, simultaneous expression of WT1 significantly increased the luciferase activity driven by Bcl-xL promoter. Taken together, these results strongly argue that WT1 up-regulates the expression of Bcl-xL at the transcriptional as well as translational level.

17-AAG-mediated Down-modulation of WT1 Sensitizes Leukemic Cells to TRAIL

We have previously shown that Hsp90 inhibition down-regulated WT1 and its target proteins in leukemia cells in vitro as well as in vivo in tumor xenografts (27). We wanted to investigate whether or not WT1 down-regulation induced by inhibition of Hsp90 is also associated with reduced levels of Bcl-xL. A dose-dependent reduction of WT1 and Bcl-xL protein levels was observed in cells treated with the Hsp90 inhibitor, 17-AAG (Fig. 2F). Similarly, 17-AAG treatment resulted in reduced expression of WT1 and Bcl-xL in K562 cell xenograft tumors (data not shown), suggesting that the presence of WT1 is crucial for Bcl-xL expression in leukemia cells. Numerous studies have shown that TRAIL resistance can be overcome by the combined application of chemotherapeutic drugs and natural products (40–42). Therefore, we also examined the importance of WT1 down-regulation by Hsp90 inhibition in potentiating TRAIL-induced apoptosis in myeloid leukemia cells. As shown in Fig. 2G, K562 leukemia cells when compared with THP-1 and MV4-11 cells were relatively resistant to TRAIL or 17-AAG treatment. However, apoptosis was greatly enhanced in all three cell lines when 17-AAG was combined with TRAIL. The results obtained with WT1 shRNA, in conjunction with data that Hsp90 inhibition markedly reduces WT1 expression and sensitizes leukemia cells to TRAIL, further suggest that induction of WT1 loss by 17-AAG is responsible, at least in part, for the elimination of TRAIL resistance.

In conclusion, we identified WT1 as a new determinant of TRAIL resistance in leukemia cells. Therefore, TRAIL in combination with agents that inhibit WT1 expression such as Hsp90 inhibitors might have a clinical applicability for the treatment of TRAIL-insensitive leukemia cells. In addition, these findings may provide a novel framework for overcoming TRAIL resistance of other cancer cells that show aberrant overexpression of WT1. Future preclinical work including analysis of TRAIL-induced apoptosis and WT1/Bcl-xL expression in patients with chemotherapy-sensitive and chemotherapy-resistant AML is warranted.

Acknowledgments

We thank Divya Chakravarthy and Jason Plyler for technical assistance, Jennifer Rebels for helping with flow cytometry experiments, and Dr. Kevin P. Foley for thorough review of the manuscript and valuable input.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant HD057118 (to M. R.). This work was also supported by the Castella Foundation, institutional start-up funds (to S. B.), and an institutional grant from the American Cancer Society (to S. P. I.) through the Roswell Park Cancer Institute.

- TRAIL

- tumor necrosis factor α-related apoptosis-inducing ligand

- WT1

- Wilms tumor 1

- AML

- acute myeloid leukemia

- Hsp90

- heat shock protein 90

- 17-AAG

- 7-N-allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin

- DR

- death receptor

- DcR

- decoy receptor

- PI

- propidium iodide

- NS

- nonsilencing

- KD

- knockdown

- SR

- shRNA-resistant.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ashkenazi A., Herbst R. S. (2008) To kill a tumor cell: the potential of proapoptotic receptor agonists. J. Clin. Invest. 118, 1979–1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yagita H., Takeda K., Hayakawa Y., Smyth M. J., Okumura K. (2004) TRAIL and its receptors as targets for cancer therapy. Cancer Sci. 95, 777–783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ashkenazi A. (2008) Directing cancer cells to self-destruct with proapoptotic receptor agonists. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 7, 1001–1012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Li H., Zhu H., Xu C. J., Yuan J. (1998) Cleavage of BID by caspase-8 mediates the mitochondrial damage in the Fas pathway of apoptosis. Cell 94, 491–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wang X. (2001) The expanding role of mitochondria in apoptosis. Genes Dev. 15, 2922–2933 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Abdulghani J., El-Deiry W. S. (2010) TRAIL receptor signaling and therapeutics. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 14, 1091–1108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhang L., Fang B. (2005) Mechanisms of resistance to TRAIL-induced apoptosis in cancer. Cancer Gene Ther. 12, 228–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cheng J., Hylander B. L., Baer M. R., Chen X., Repasky E. A. (2006) Multiple mechanisms underlie resistance of leukemia cells to Apo2 ligand/TRAIL. Mol. Cancer Ther. 5, 1844–1853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. MacFarlane M., Harper N., Snowden R. T., Dyer M. J., Barnett G. A., Pringle J. H., Cohen G. M. (2002) Mechanisms of resistance to TRAIL-induced apoptosis in primary B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Oncogene 21, 6809–6818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fakler M., Loeder S., Vogler M., Schneider K., Jeremias I., Debatin K. M., Fulda S. (2009) Small molecule XIAP inhibitors cooperate with TRAIL to induce apoptosis in childhood acute leukemia cells and overcome Bcl-2-mediated resistance. Blood 113, 1710–1722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Riccioni R., Pasquini L., Mariani G., Saulle E., Rossini A., Diverio D., Pelosi E., Vitale A., Chierichini A., Cedrone M., Foà R., Lo Coco F., Peschle C., Testa U. (2005) TRAIL decoy receptors mediate resistance of acute myeloid leukemia cells to TRAIL. Haematologica 90, 612–624 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kim I. K., Jung Y. K., Noh D. Y., Song Y. S., Choi C. H., Oh B. H., Masuda E. S. (2003) Functional screening of genes suppressing TRAIL-induced apoptosis: distinct inhibitory activities of Bcl-XL and Bcl-2. Br. J. Cancer 88, 910–917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Haber D. A., Buckler A. J., Glaser T., Call K. M., Pelletier J., Sohn R. L., Douglass E. C., Housman D. E. (1990) An internal deletion within an 11p13 zinc finger gene contributes to the development of Wilms tumor. Cell 61, 1257–1269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yang L., Han Y., Suarez Saiz F., Minden M. D. (2007) A tumor suppressor and oncogene: the WT1 story. Leukemia 21, 868–876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ariyaratana S., Loeb D. M. (2007) The role of the Wilms tumor gene (WT1) in normal and malignant hematopoiesis. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 9, 1–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Han Y., San-Marina S., Liu J., Minden M. D. (2004) Transcriptional activation of c-myc proto-oncogene by WT1 protein. Oncogene 23, 6933–6941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Simpson L. A., Burwell E. A., Thompson K. A., Shahnaz S., Chen A. R., Loeb D. M. (2006) The antiapoptotic gene A1/BFL1 is a WT1 target gene that mediates granulocytic differentiation and resistance to chemotherapy. Blood 107, 4695–4702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tschan M. P., Gullberg U., Shan D., Torbett B. E., Fey M. F., Tobler A. (2008) The hDMP1 tumor suppressor is a new WT1 target in myeloid leukemias. Leukemia 22, 1087–1090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Morrison D. J., English M. A., Licht J. D. (2005) WT1 induces apoptosis through transcriptional regulation of the proapoptotic Bcl-2 family member Bak. Cancer Res. 65, 8174–8182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rosenfeld C., Cheever M. A., Gaiger A. (2003) WT1 in acute leukemia, chronic myelogenous leukemia, and myelodysplastic syndrome: therapeutic potential of WT1 targeted therapies. Leukemia 17, 1301–1312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Oka Y., Tsuboi A., Kawakami M., Elisseeva O. A., Nakajima H., Udaka K., Kawase I., Oji Y., Sugiyama H. (2006) Development of WT1 peptide cancer vaccine against hematopoietic malignancies and solid cancers. Curr. Med. Chem. 13, 2345–2352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ogawa H., Tamaki H., Ikegame K., Soma T., Kawakami M., Tsuboi A., Kim E. H., Hosen N., Murakami M., Fujioka T., Masuda T., Taniguchi Y., Nishida S., Oji Y., Oka Y., Sugiyama H. (2003) The usefulness of monitoring WT1 gene transcripts for the prediction and management of relapse following allogeneic stem cell transplantation in acute type leukemia. Blood 101, 1698–1704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lapillonne H., Renneville A., Auvrignon A., Flamant C., Blaise A., Perot C., Lai J. L., Ballerini P., Mazingue F., Fasola S., Dehée A., Bellman F., Adam M., Labopin M., Douay L., Leverger G., Preudhomme C., Landman-Parker J. (2006) High WT1 expression after induction therapy predicts high risk of relapse and death in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 24, 1507–1515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sugiyama H. (2002) Wilms tumor gene WT1 as a tumor marker for leukemic blast cells and its role in leukemogenesis. Methods Mol. Med. 68, 223–237 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Weisser M., Kern W., Rauhut S., Schoch C., Hiddemann W., Haferlach T., Schnittger S. (2005) Prognostic impact of RT-PCR-based quantification of WT1 gene expression during MRD monitoring of acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 19, 1416–1423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Boublikova L., Kalinova M., Ryan J., Quinn F., O'Marcaigh A., Smith O., Browne P., Stary J., McCann S. R., Trka J., Lawler M. (2006) Wilms tumor gene 1 (WT1) expression in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a wide range of WT1 expression levels, its impact on prognosis, and minimal residual disease monitoring. Leukemia 20, 254–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bansal H., Bansal S., Rao M., Foley K. P., Sang J., Proia D. A., Blackman R. K., Ying W., Barsoum J., Baer M. R., Kelly K., Swords R., Tomlinson G. E., Battiwalla M., Giles F. J., Lee K. P., Padmanabhan S. (2010) Heat shock protein 90 regulates the expression of Wilms tumor 1 protein in myeloid leukemias. Blood 116, 4591–4599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Elmaagacli A. H., Koldehoff M., Peceny R., Klein-Hitpass L., Ottinger H., Beelen D. W., Opalka B. (2005) WT1 and BCR-ABL specific small interfering RNA have additive effects in the induction of apoptosis in leukemic cells. Haematologica 90, 326–334 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Salameh A., Galvagni F., Anselmi F., De Clemente C., Orlandini M., Oliviero S. (2010) Growth factor stimulation induces cell survival by c-Jun: ATF2-dependent activation of Bcl-xL. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 23096–23104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Malhi H., Gores G. J. (2006) TRAIL resistance results in cancer progression: a TRAIL to perdition? Oncogene 25, 7333–7335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hietakangas V., Poukkula M., Heiskanen K. M., Karvinen J. T., Sistonen L., Eriksson J. E. (2003) Erythroid differentiation sensitizes K562 leukemia cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis by down-regulation of c-FLIP. Mol. Cell Biol. 23, 1278–1291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Danial N. N., Korsmeyer S. J. (2004) Cell death: critical control points. Cell 116, 205–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Trauzold A., Siegmund D., Schniewind B., Sipos B., Egberts J., Zorenkov D., Emme D., Röder C., Kalthoff H., Wajant H. (2006) TRAIL promotes metastasis of human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Oncogene 25, 7434–7439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Finucane D. M., Bossy-Wetzel E., Waterhouse N. J., Cotter T. G., Green D. R. (1999) Bax-induced caspase activation and apoptosis via cytochrome c release from mitochondria is inhibitable by Bcl-xL. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 2225–2233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jürgensmeier J. M., Xie Z., Deveraux Q., Ellerby L., Bredesen D., Reed J. C. (1998) Bax directly induces release of cytochrome c from isolated mitochondria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 4997–5002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Medema J. P., Scaffidi C., Krammer P. H., Peter M. E. (1998) Bcl-xL acts downstream of caspase-8 activation by the CD95 death-inducing signaling complex. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 3388–3393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Srinivasan A., Li F., Wong A., Kodandapani L., Smidt R., Jr., Krebs J. F., Fritz L. C., Wu J. C., Tomaselli K. J. (1998) Bcl-xL functions downstream of caspase-8 to inhibit Fas- and tumor necrosis factor receptor 1-induced apoptosis of MCF7 breast carcinoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 4523–4529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bai J., Sui J., Demirjian A., Vollmer C. M., Jr., Marasco W., Callery M. P. (2005) Predominant Bcl-xL knockdown disables antiapoptotic mechanisms: tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand-based triple chemotherapy overcomes chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer cells in vitro. Cancer Res. 65, 2344–2352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Song J. J., An J. Y., Kwon Y. T., Lee Y. J. (2007) Evidence for two modes of development of acquired tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand resistance: involvement of Bcl-xL. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 319–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shankar S., Srivastava R. K. (2004) Enhancement of therapeutic potential of TRAIL by cancer chemotherapy and irradiation: mechanisms and clinical implications. Drug Resist. Updat. 7, 139–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Carter B. Z., Mak D. H., Schober W. D., Dietrich M. F., Pinilla C., Vassilev L. T., Reed J. C., Andreeff M. (2008) Triptolide sensitizes AML cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis via decrease of XIAP and p53-mediated increase of DR5. Blood 111, 3742–3750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hasegawa H., Yamada Y., Komiyama K., Hayashi M., Ishibashi M., Yoshida T., Sakai T., Koyano T., Kam T. S., Murata K., Sugahara K., Tsuruda K., Akamatsu N., Tsukasaki K., Masuda M., Takasu N., Kamihira S. (2006) Dihydroflavonol BB-1, an extract of natural plant Blumea balsamifera, abrogates TRAIL resistance in leukemia cells. Blood 107, 679–688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]