Background: Polysialic acid (PSA) promotes neuroplasticity, and overexpression of polysialyltransferase genes augments brain repair.

Results: Extracellular application of a purified bacterial polysialyltransferase (PSTNm) produces PSA on vertebrate cells in vitro and in vivo, and the product is biologically active.

Conclusion: Polysialylation of cells by PSTNm is rapid, persistent, but not permanent.

Significance: A PSTNm-based approach may provide an alternative to polysialyltransferase gene therapy.

Keywords: Adhesion, Bioengineering, Glycobiology, Glycoprotein Biosynthesis, Glycosyltransferases, Cell Surface, Neuroplasticity, Polysialic Acid, Polysialyltransferase, Tissue Repair

Abstract

In vertebrates, polysialic acid (PSA) is typically added to the neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) in the Golgi by PST or STX polysialyltransferase. PSA promotes plasticity, and its enhanced expression by viral delivery of the PST or STX gene has been shown to promote cellular processes that are useful for repair of the injured adult nervous system. Here we demonstrate a new strategy for PSA induction on cells involving addition of a purified polysialyltransferase from Neisseria meningitidis (PSTNm) to the extracellular environment. In the presence of its donor substrate (CMP-Neu5Ac), PSTNm synthesized PSA directly on surfaces of various cell types in culture, including Chinese hamster ovary cells, chicken DF1 fibroblasts, primary rat Schwann cells, and mouse embryonic stem cells. Similarly, injection of PSTNm and donor in vivo was able to produce PSA in different adult brain regions, including the cerebral cortex, striatum, and spinal cord. PSA synthesis by PSTNm requires the presence of the donor CMP-Neu5Ac, and the product could be degraded by the PSA-specific endoneuraminidase-N. Although PSTNm was able to add PSA to NCAM, most of its product was attached to other cell surface proteins. Nevertheless, the PSTNm-induced PSA displayed the ability to attenuate cell adhesion, promote neurite outgrowth, and enhance cell migration as has been reported for endogenous PSA-NCAM. Polysialylation by PSTNm occurred in vivo in less than 2.5 h, persisted in tissues, and then decreased within a few weeks. Together these characteristics suggest that a PSTNm-based approach may provide a valuable alternative to PST gene therapy.

Introduction

Sialic acid monomers can be polymerized into a long linear α2,8-linked homopolymer, polysialic acid (PSA),4 which in vertebrates is typically linked to the fifth Ig-like domain of the neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM). Two Golgi polysialyltransferases, ST8SiaII (STX) and ST8SiaIV (PST) are known to carry out this polysialylation, with either enzyme capable of synthesizing long PSA chains (1). By virtue of the polyanionic charge of its repeating subunit, PSA occupies an enormous hydrated volume that hinders close association between cell membranes. It thereby can act as a global negative regulator of cell interactions, i.e. not only via NCAM but other surface molecules, such as L1, integrins, and cadherins as well (2–4). This global action creates permissive conditions for structural remodeling in tissues (4).

PSA-induced plasticity is particularly useful in the developing nervous system, where this polymer is abundantly expressed on neuroectodermal progenitors, neurons and some glial cells. Its presence promotes cell migration (5–8), helps growing processes to bundle, sprout and branch appropriately (9–12) and prevents formation of ectopic connections (13, 14). PSA expression is subsequently down-regulated, except in a few brain regions that retain a capacity for morphological and/or physiological plasticity in adulthood (4, 15, 16).

The down-regulation of PSA in the CNS largely coincides with the stabilization of neural connections and could contribute to the refractory nature of the adult CNS to endogenous repair following injury or disease. We and others have shown that reintroduction of PSA expression in the lesioned adult nervous system can restore some plasticity and thereby facilitate repair mechanisms. For example, overexpression of the polysialyltransferase gene in vivo promotes regeneration of lesioned axons and recruitment of neural progenitors into lesions (17–20). Similarly, introduction of the gene into cells in culture has improved cell grafting therapies using Schwann cells in spinal cord injury (21–24) or stem cell-derived progenitors (for review, see Ref. 18).

For therapeutics, the use of viral vectors to introduce a polysialyltransferase has some disadvantages: the induction of PSA is relatively slow, expression is restricted to cells that can be reached and infected by the virus and can persist beyond the period of repair, and there are significant practical challenges with respect to clinical implementation. A potential alternative would be a method to rapidly and transiently up-regulate PSA, long enough for repair to occur, with appropriate spatiotemporal characteristics. One such candidate would be the polysialyltransferase enzyme itself (25). Although mammalian PST/STX are low abundance membrane proteins that operate in the Golgi, a purified Neisseria meningitidis α2,8-polysialyltransferase (PSTNm) has potential, in that it operates in the extracellular environment, uses a commercially available nontoxic donor substrate (CMP-Neu5Ac), and produces a polymer chemically identical to mammalian PSA (26, 27). This enzyme has proven to be effective in adding PSA to therapeutic proteins in vitro to augment their in vivo pharmacokinetics (27). The aim of the present study was to test the ability of purified PSTNm to synthesize PSA on live cells in vitro and in vivo. The results reveal that this direct approach rapidly produces substantial amounts of PSA on the surface of cells both in culture and within the brain, and that this PSA has biological activity that is potentially appropriate for therapeutic application.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Preparation of PSTNm and CMP-Neu5Ac

Cloning and expression of PSTNm from N. meningitidis 992B and its production and purification as a soluble fusion protein (MalE-Δ19PSTNM) have been described previously (26, 27). In brief, after expression in Escherichia coli AD202 (E. coli Genetic Stock Center CGSC 7297), the enzyme was purified from the supernatant of the cell lysate (after centrifugation at 27,000 × g) on a 5-ml heparin HiTrap HP column (GE Healthcare) with a linear gradient of 0–60% B using buffers A (PBS, pH 7.4) and B (PBS, pH 7.4, + 2 m NaCl) followed by desalting on a 5-ml HiTrap desalting column (GE Healthcare) using PBS, pH 7.4. The donor CMP-NeuAc was enzymatically synthesized and purified as previously described (28, 29). Purified enzyme and donor were both stored at −80 °C.

Cell Cultures

Primary Schwann cells (SCs) were prepared as described earlier (24). Sciatic nerves of adult Fischer rats were dissociated and SCs cultured in DMEM/10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) supplemented with bovine pituitary extract (20 μg/ml; Invitrogen), forskolin (2.5 μm), and heregulin (2.5 nm; Genentech) for at least 3 passages. Purity of these cultures was ∼ 95–98%. SCs were then infected with EGFP or EGFP and PST using lentiviral vectors (Invitrogen).

Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells and DF-1 chicken fibroblasts were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and 1% Pen-Strep. Generation of CHO cells stably transfected with NCAM-140 vector has been described earlier (3).

Mouse embryonic stem cells expressing GFP under the HB9 motoneuron-specific promoter (HB9::GFP mESC) (30, 31) were cultured in ES medium (knock-out DMEM, 1% MEM-NEAA, 1% l-glutamine, 1% Pen-Strep (all from Invitrogen), 2000 units/μl LIF, 1% nucleoside (both from Millipore), 15% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone), β-mercaptoethanol (Invitrogen)). For detailed motoneuronal differentiation, see Ref. 31. In brief, to initiate differentiation, cells were transferred into DKF10 medium (50/50 of DMEM HG/Ham-F12, 10% knock-out serum replacement (Invitrogen), 1% Pen-Strep, 1% l-Glu, 1 unit/μl heparin, β-mercaptoethanol, 2.4% N2-supplement (Invitrogen)). Embryoid bodies (EBs) form after 1 day in culture, and after 2 days they were treated with retinoic acid (1 μm) and sonic hedgehog analog (1.5 μm purmorphamine (32)) to induce motoneuronal differentiation. Cells up-regulated GFP and started to grow neurites and to emigrate from the EBs. Increasing these events produces a carpet of cells and neurites so dense that tracing and measuring of axons become unfeasible. Therefore, to assess PSA effects, the induced spreading of neurites and cells on the dish floor was estimated by measuring the density of GFP fluorescence per surface area (NIH ImageJ 1.45).

For polysialylation of cultures by PSTNm, the enzyme (30 milliunits/ml) and CMP-Neu5Ac substrate (10 mm) were added to the culture medium for 2 h at 37 °C in the absence of serum and antibiotics. After 2 h, cells were returned to their usual medium. Cultures of differentiating mESCs into motoneurons were treated on day 1 and day 3 of differentiation.

For trypsinization of CHO cells, cultures were treated with 5 mm EDTA in Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS) at 37 °C for 10 min to detach cells from the dish. The cell suspensions were incubated with PSTNm and CMP-Neu5Ac for 2 h at 37°c, washed in PBS, then treated with 0.04% trypsin in calcium-free HBSS with 10 mm CaCl2 for 25 min at 37 °C. Controls were incubated in calcium-free HBSS with 10 mm CaCl2. After washing, cells were processed for immunostaining.

Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (10 min) and incubated overnight with the 5A5 mouse IgM anti-PSA antibody (1:2000). A Cy3-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:800) was used to visualize staining.

Schwann Cell Adhesion Assay

To assess the effect of PSA on SC cell-cell adhesion, suspensions of 10,000 SCs prelabeled red with CellTracker Orange CMRA (Invitrogen) were seeded on a confluent monolayer of GFP-expressing SCs in a 12-well plate, in a total volume of 500 μl of PBS. The cultures were mixed carefully using a cross-shaped horizontal motion for 10 s. After a 10- or 20-min adhesion time at room temperature, the liquid with floating cells was slowly removed and the culture gently rinsed with 500 μl of PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and then washed in PBS. Red cells that adhered to the monolayer were counted in three equal fields, using a 10× objective. The following four conditions were analyzed: (i) both red and green cells were pretreated with PSTNm and donor substrate for 2 h before co-culture (SC + PSTNm/S); (ii) both red and green cells overexpressed the PST gene (SC-PST); (iii) both red and green cells overexpressed the PST gene and were pretreated with PSTNm and donor substrate for 2 h (SC-PST + PSTNm/S); (iv) control cells were induced neither by PST gene nor by PSTNm (SC). All conditions were repeated two times in triplicate. The results were compared using a two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post tests (GraphPad Prism 5.0c), and data expressed as means ± S.E.

Immunoblot Analysis

Samples were extracted in lysis buffer (1% Nonidet P-40, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 25 mm Hepes, PBS, pH 7.4) supplemented with protease inhibitors (Sigma). Purified endoneuraminidase-N (endo-N) (14) was used to specifically cleave PSA from NCAM (40 units/μl, 60 min, 37 ºC). Samples with equal total protein amounts were separated on 6% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Millipore). After blocking for 1 h (5% nonfat dry milk in TBS-T), a rabbit polyclonal IgG anti-mouse NCAM antibody (RO25b, 1:7500) was added overnight at 4 ºC. Following washing in TBS-T (three times for 5 min), an anti-rabbit IgG peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:7500; Jackson Laboratories) was applied for 90 min before washing again in TBS-T (six times for 5 min). For PSA immunoblotting, the 5A5 mouse monoclonal IgM (1:500) and a peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgM secondary antibody (1:5000) were used instead. Finally, the signal was detected using the ECL system (Pierce).

In Vivo Injection of PSTNm

All animal handling and experimentation were conducted according to institutional and NIH guidelines. Under deep pentobarbital anesthesia, 4–5-month-old male mice (BALB/c) were prepared for surgery and stabilized in a stereotaxic frame. A small opening was drilled in the skull (bregma: 0.3 mm posterior; 1.5 mm lateral), and a 1-μl mixture of PSTNm (3 μg/μl) and CMP-Neu5Ac substrate (5 mm) was slowly injected in the cerebral cortex or deep into the striatum, using a fine capillary pipette. For the spinal cord, similar injections were performed at the lumbar level (L4–5). Control injections used either PSTNm or donor substrate alone. Mice with spinal injections were sacrificed 1 or 2 days later. Those with cortical or striatal injections were sacrificed 2.5, 4, or 6 h after injections as well as 1, 2, 7, 14, 21, or 28 days later (five mice/treatment after 1 day and three animals/treatment for the remaining time points). Three NCAM-null animals with cortical injections of PSTNm/substrate were sacrificed after 2 days. All animals were perfused with 25 ml of a 7.4 pH phosphate buffer saline solution followed by 25 ml of a 4% paraformaldehyde, 0.1 m, 7.4 pH phosphate buffer solution. The brain and spinal cord were dissected out and postfixed for 48 h at 4 °C in the same fixative. The samples were sectioned at 50 μm using a vibratome and immunostained for PSA (5A5 mouse monoclonal IgM antibody, 1:2000 and Cy3-goat anti-mouse IgM secondary antibody, 1:800) (14). Immunostaining was imaged using a Zeiss 510 confocal microscope.

RESULTS

PSTNm Synthesizes PSA on Surfaces of Cultured Cells

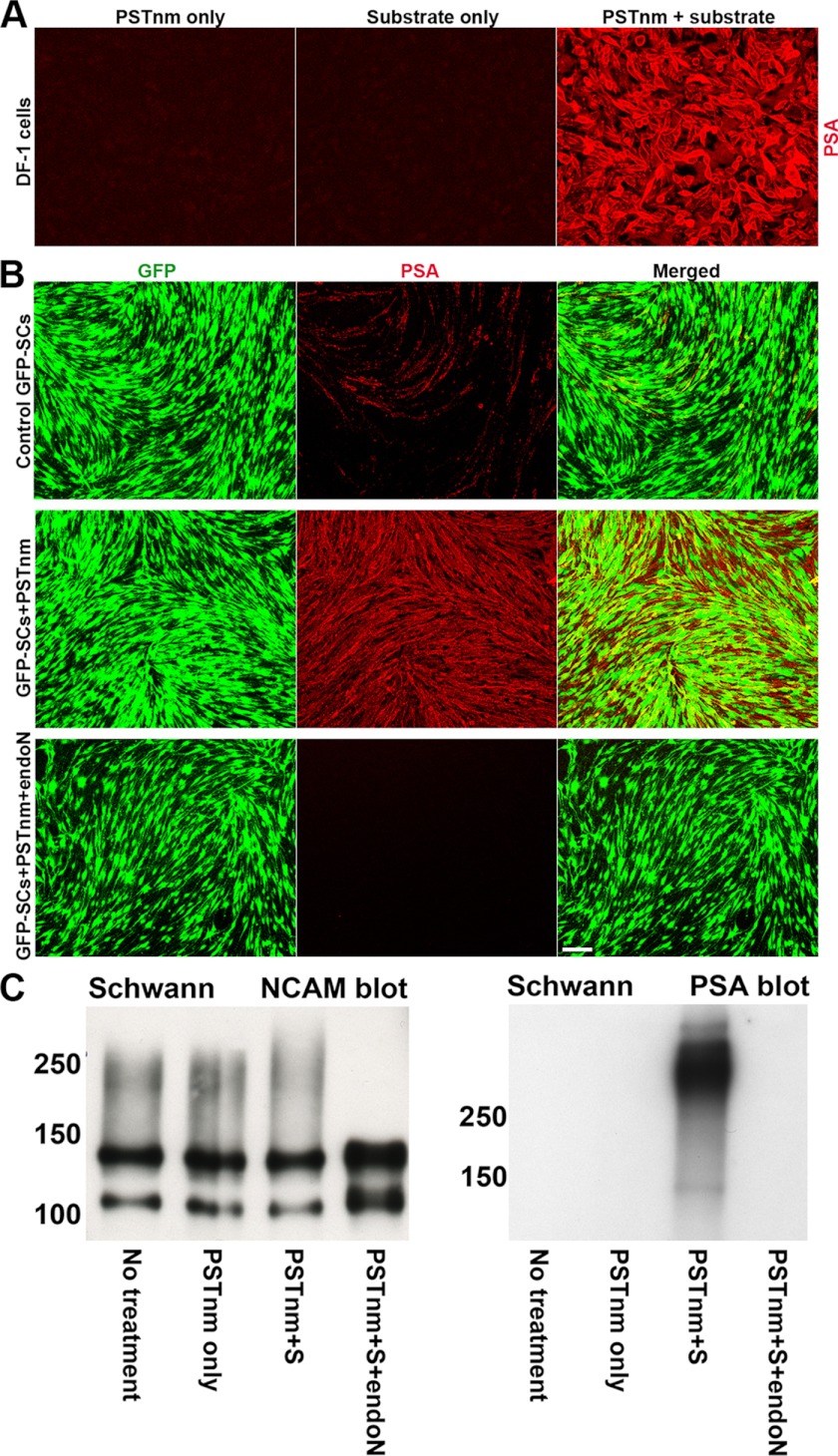

To test the efficacy of PSTNm in vitro, cell cultures derived from various vertebrate sources were incubated with the enzyme (30 milliunits/ml) and its donor substrate, CMP-Neu5Ac (10 mm) for 2 h. These studies utilized the PSA-negative DF-1 chicken fibroblast cell line and primary cultures of rat SCs that display low, sporadic levels of endogenous PSA in a few cells. Exposure of DF-1 cells to either PSTNm or donor alone did not result in PSA synthesis. However, when the cells were incubated with both enzyme and donor substrate, high levels of PSA immunoreactivity appeared on their surfaces (Fig. 1A). When the SC cultures were preincubated with PSTNm and its substrate, high levels of PSA expression were observed on the surface of all cells in culture (Fig. 1B). Post-treatment with endo-N, an enzyme that specifically cleaves PSA (33), completely abolished expression from the PSTNm/substrate-treated cultures (Fig. 1B). Similar results were obtained when the cell lysates were probed for NCAM and PSA (Fig. 1C).

FIGURE 1.

Addition of PSTNm/substrate induces high levels of PSA on DF-1 and Schwann cells in culture. PSA was detected using the highly specific 5A5 monoclonal antibody. A, chicken DF-1 fibroblast cells are known to have no detectable PSA expression, and incubation either with PSTNm or donor substrate alone produced no PSA. However, simultaneous addition of PSTNm and CMP-Neu5Ac produced high levels of PSA expression on cell surfaces (red). B, rat primary GFP-SC (green) cultures were treated with PSTNm/substrate and then fixed and immunostained for PSA. Control cultures express insignificant amounts of PSA (red). However, with PSTNm/substrate treatment, very high levels of PSA expression are observed on both the cell bodies and processes of GFP-SCs. Incubation with the PSA-specific endo-N completely abolished PSTNm-induced PSA staining. Scale bar, 100 μm. C, SC cultures, with or without PSTNm treatment, were processed for electrophoresis. Immunoblotting for NCAM revealed the presence of the 120- and 140-NCAM isoforms in untreated cells, with a light polysialylation smear extending to about 250 kDa. The same pattern was observed with addition of PSTNm alone. Incubation of cells with both enzyme and donor substrate shifted the smear to higher molecular masses. Addition of endo-N completely eliminated all the PSA-associated smears. Immunoblotting for PSA revealed that PSTNm and donor substrate produced a heavy band above 250 kDa, which was absent in control cells or samples treated with enzyme alone. This band disappeared completely after endo-N treatment.

Injection of PSTNm Produces PSA in Brain Tissues in Vivo

To test the ability of PSTNm to produce PSA on brain cells in vivo, 1 μl of enzyme (3 μg/μl) and donor (5 mm) mixture in PBS was stereotaxically injected in the cerebral cortex, striatum, or spinal cord, and 24 h later the tissues were fixed by perfusion for PSA detection by immunohistochemistry. In each case, injection of the enzyme alone did not produce detectable PSA (Fig. 2, A, D, and F). In the cerebral cortex, the enzyme/substrate combination produced widespread PSA immunoreactivity around the needle track, with clear variability in size and shape of polysialylated area between samples (Fig. 2, B and K). The PSTNm-induced PSA could be removed by treatment with endo-N (Fig. 2C). When injected into the striatum, PSTNm and donor again diffused readily and produced intense PSA staining (Fig. 2, E and L). However, bundles of myelinated fibers running through the striatum were not well polysialylated (Fig. 2E). Examination of the injected spinal cord also revealed large amounts of PSA, with immunostaining often extending over the entire dorso-ventral span of the cord (Fig. 2, G–J) and as far as 3 mm along the rostro-caudal axis (Fig. 2J). PSA expression occurred throughout the neuropil and on cell surfaces (Fig. 2H) as well as on axonal pathways such as the corticospinal tract (Fig. 2I).

FIGURE 2.

In vivo administration of PSTNm and donor substrate induces high levels of PSA expression in brain tissues. PSTNm and CMP-Neu5Ac were co-injected into the cerebral cortex, striatum, or spinal cord. Animals were perfused 24 h later and immunostained for PSA. Injection of enzyme alone produced no PSA in all three regions (A, D, and F; arrow, needle track). With co-administration of PSTNm and substrate, large amounts of PSA were detected in the cerebral cortex (B), and treatment with endo-N (C) completely abolished this staining (transverse sections). Although large portions of the striatum (transverse section) were polysialylated following injection of PSTNm and donor substrate (E), the dense bundles of myelinated fibers that traverse the striatum (stars) showed little or no PSA staining. High PSA expression was also observed in the spinal cord (G) (sagittal section), with good rostro-caudal as well as dorso-ventral extension of staining (SG, endogenous PSA in substantia gelatinosa). Scale bars, 100 μm in A–G. An example from the spinal gray matter (H) shows PSA staining in the neuropil (star) as well as on cell surfaces (arrows), with the cytoplasm of cells remaining devoid of PSA (dark). Arrowhead indicates a capillary. Scale bar, 50 μm. In the white matter, such as the corticospinal tract (I), PSA was readily visible on axons (arrows). Scale bar, 50 μm. J, view of a sagittal spinal section shows an example with good rostro-caudal spread of PSA staining, which sometimes exceeded 3 mm. Note the irregular shape of the stained area (double arrow indicates the extent of PSA staining. Dotted line, injection track. Scale bar, 100 μm). The bottom drawings are overlays of coronal maps (red, blue, green, and yellow) from four representative samples with cortical injection (K) and four samples with striatal injection (L) showing the variability in size and shape of the area of PSA expression among PSTNm/S-injected animals. Each color represents one sample. Cx, cerebral cortex; S, striatum; CC, corpus callosum; V, lateral ventricle.

Brain Polysialylation by PSTNm Is Rapid, Persistent, but Not Permanent

The kinetics of PSA production by PSTNm was examined in the cerebral cortex and striatum. In the cerebral cortex PSA synthesis was readily visible 2 h 30 min after injection (Fig. 3A) and by 6 h reached a plateau level similar to the amount observed after 1 day. These high levels were maintained for a few days (Fig. 3B) and then decreased gradually over the following weeks. Although PSA was still detected by 3 weeks, its amounts were considerably decreased (Fig. 3C). In the striatum, however, whereas PSA was also present by 2 h 30 min (Fig. 3D), the decrease was more rapid, with almost no staining remaining after 2 weeks (Fig. 3E). These observations attest to the rapidity of brain polysialylation with the PSTNm approach and suggest that the rate of elimination of PSTNm-induced PSA can vary among brain regions.

FIGURE 3.

In vivo production of PSA by PSTNm is rapid and persistent but not permanent. PSA expression by PSTNm in the cerebral cortex was detected within 2 h 30 min after injection, was still intense after 2 weeks, and began to decrease in amount after 3 weeks. In the striatum, this reduction was already more pronounced by 2 weeks. Arrow, needle track; arrowheads, diffusion and polysialylation along the corpus callosum (cc); stars, bundles of myelinated fibers. Transverse sections are shown. Scale bar, 100 μm.

PSTNm Can Synthesize PSA on NCAM, but Mostly Adds PSA to Other Cell Surface Protein Acceptors

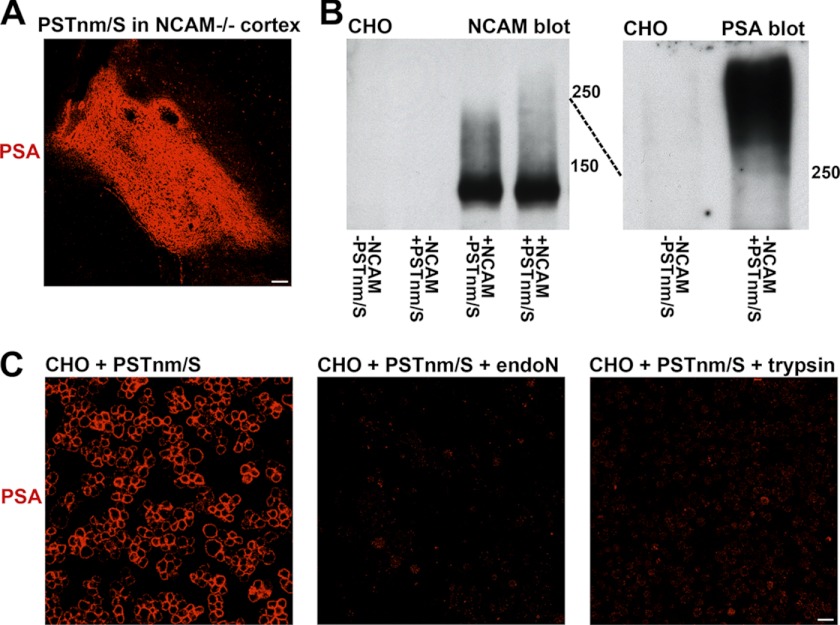

SDS-PAGE immunoblots for NCAM of cultured SCs showed that these cells express the 120- and 140-NCAM isoforms, with a light smear characteristic of polysialylated material extending below 250 kDa (Fig. 1C). Treatment with PSTNm and donor substrate extended the smear to above 250 kDa, suggesting additional NCAM polysialylation by the enzyme, and the entire smear was absent after endo-N incubation (Fig. 1C). When the same extracts of PSTNm/donor-treated cells were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-PSA, an intense band of PSA-positive material was revealed, most of which displayed electrophoretic characteristics different than those found in the NCAM immunoblots. This difference suggested that NCAM is not the dominant acceptor for the synthesis of PSA by PSTNm. To verify the attachment of PSA to acceptors other than NCAM, PSTNm and donor substrate were injected into the cerebral cortex of NCAM-null animals. Large amounts of PSA immunoreactivity were produced (Fig. 4A), confirming that the presence of NCAM is not required for PSTNm synthesis of PSA.

FIGURE 4.

PSTNm adds PSA to NCAM as well as to other surface proteins. A, injection of PSTNm and donor substrate in the cerebral cortex of NCAM-null mice (lacking all NCAM isoforms) produced high levels of PSA expression as shown by immunostaining 2 days later (sagittal section shown; scale bar, 100 μm). B, PSTNm treatment and NCAM immunoblotting of CHO cells showed no band in control cells. An NCAM-140 band was detected when cells were transfected with this isoform. This NCAM was lightly polysialylated (smear below 250 kDa), and the PSA smear was extended above 250 kDa when cells were incubated with PSTNm and substrate. PSA immunoblotting of preparations of CHO cells (with no NCAM construct) showed that PSTNm produced a strong band above 250 kDa, which was absent in control samples. C, suspensions of CHO cells were incubated with PSTNm and donor substrate and immunostained for PSA. Staining was clearly present on their surfaces, and it was completely removed following treatment of the live cells with either endo-N or trypsin. Scale bar, 20 μm.

To characterize further the attachment sites for the PSA produced by PSTNm, studies were carried out with CHO cells that express undetectable levels of PSA and its typical carrier NCAM (Fig. 4B), or that have been stably transfected with NCAM-140. With the NCAM-140 CHO cells, immunoblotting for NCAM showed a band around 140 kDa with a polysialylation smear below 250 kDa, and incubation of these cells with PSTNm and donor substrate extended the NCAM smear above 250 kDa. However, even with addition of PSTNm most of the NCAM-140 remained unpolysialylated, similar to the results observed with SCs. Finally, with the NCAM-null CHO cells, treatment with PSTNm and donor generated large amounts of PSA migrating above 250 kDa (Fig. 4B), again indicating the presence of major acceptor(s) other than NCAM.

To investigate further the nature of the non-NCAM carrier(s) of PSTNm-produced PSA, live untransfected CHO cells, treated with PSTNm/donor, were trypsinized and washed to remove surface proteins prior to immunostaining. Under these conditions, no PSA immunostaining remained (Fig. 4C), suggesting that the acceptors for PSTNm are cell surface proteins.

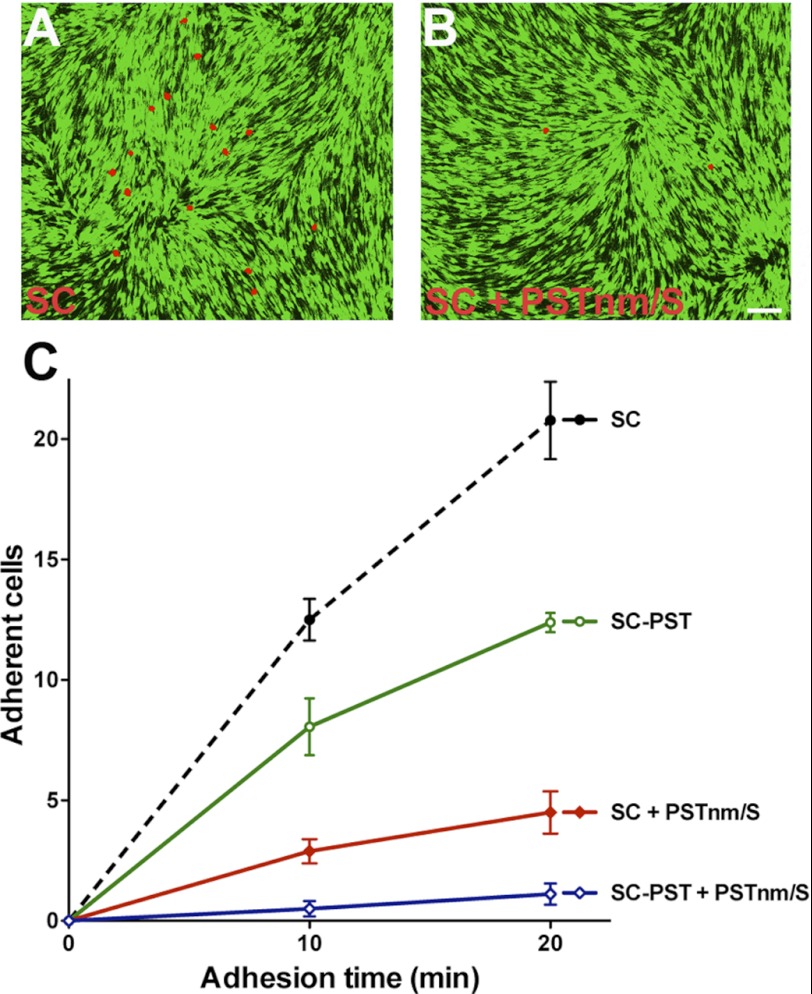

PSA Produced by PSTNm Attenuates Cell-Cell Adhesion

The addition of PSA to non-NCAM acceptors raises the critical question as to whether the PSTNm-produced polymer exhibits the biological activity of endogenous PSA attached to NCAM. The best documented activity of PSA-NCAM is its ability to attenuate cell adhesion (3). To assess the effect of PSTNm-induced PSA on cell adhesion, suspensions of red-labeled SCs were allowed to settle on a monolayer of GFP-expressing SCs for 10 or 20 min, and adherent cells were counted. As expected, overexpression of the mammalian PST in SCs significantly lowered the numbers of adherent red cells (p < 0.01) (Fig. 5). Pretreatment of the cells with PSTNm and donor also markedly reduced adhesion of SCs to each other (p < 0.01). Addition of PSTNm and donor to the PST-transfected SCs produced an even greater effect (p < 0.01), with almost complete inhibition of adhesion.

FIGURE 5.

PSA produced by PSTNm attenuates cell-cell adhesion. Suspensions of red-labeled SCs were seeded onto a confluent monolayer of GFP-expressing SCs, and the red cells that adhered to the monolayer were examined 10 or 20 min later. A, example shows red-labeled SCs that adhered after 20-min attachment time. B, there were much fewer adherent cells following polysialylation by PSTNm. Scale bar, 100 μm. C, quantification revealed that PSTNm-produced PSA inhibits cell-cell adhesion even more effectively (SC + PSTNm/S) than PSA produced by introduction of the PST gene (SC-PST). The effects of PSTNm and PST are additive (SC-PST + PSTNm/S) (two-way ANOVA: p < 0.0001, F = 128.7, n = 6 for each data point, error bars: S.E.).

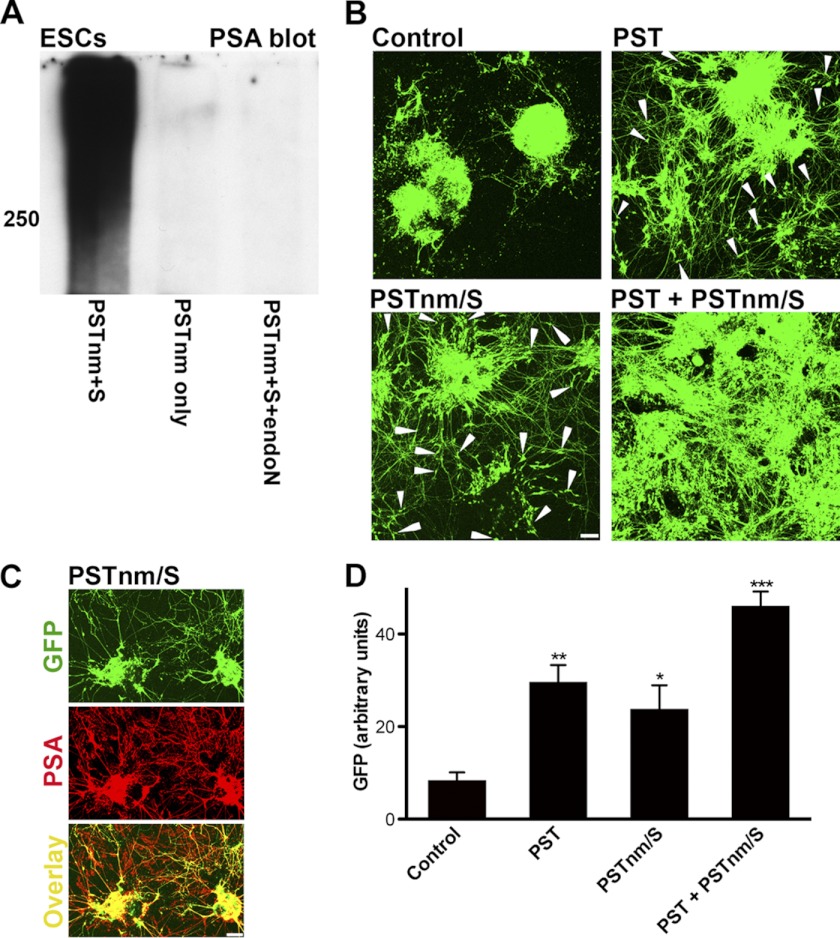

PSTNm-induced PSA Facilitates Neurite Outgrowth and Cell Migration

PSA is known to facilitate neurite outgrowth and cell migration (for review, see Ref. 4). To evaluate PSTNm with respect to these parameters, mouse embryonic stem cells expressing GFP under a motoneuron-specific promotor (HB9::GFP mESC) (30) were treated with enzyme and donor substrate to produce PSA (Fig. 6A) during differentiation into motoneurons. GFP-positive neurons in control ESC-derived EBs began extending neurites on day 4 of the differentiation process. The GFP-positive cell bodies also began to migrate away from the EBs either along axon bundles or freely on the dish floor. Introduction of the mouse PST gene into these cells to enhance their PSA expression increased neurite outgrowth and cell emigration from EBs, which becomes very obvious on day 6 (Fig. 6, B and D). When control cells were treated with PSTNm and donor, the patterns of neurite growth and cell migration were comparable with the effects produced by the PST gene (Fig. 6, B–D). Addition of PSTNm to cultures that express the PST gene had an additive effect, with much extensive neurite outgrowth and a complete disintegration of the EBs into migrating cells on the dish floor (Fig. 6B).

FIGURE 6.

PSTNm-induced PSA promotes neurite outgrowth and cell migration. Theses studies utilized mESCs expressing GFP under the HB9 promoter. A, undifferentiated cultures of mESCs were processed for PSA immunoblotting. These cells have undetectable levels of PSA as shown in control samples treated with the enzyme without donor substrate. However, incubation with both PSTNm and substrate produced a large PSA band above 250 kDa, which was removed with endo-N treatment. B, EBs of these mESCs were induced to differentiate toward a motoneuronal phenotype, using retinoic acid and SHH analog. At the end of incubation on day 6, control cells had extended GFP-positive neurites. With cells that were modified to stably express mouse PST (PST), there was substantially more neurite outgrowth, and GFP-positive cell bodies were observed migrating out of the EBs (arrowheads), which started to flatten and disperse. Treatment of the EB cultures with PSTNm and donor substrate produced an effect similar to mouse PST, enhancing both neurite outgrowth and cell migration. When cells expressing mouse PST were also treated with PSTNm and substrate, the effects on neurite outgrowth and cell migration were enhanced, with EBs appearing to completely disintegrate and neurites and cells covering most of the dish floor. Scale bar, 100 μm. C, immunostaining of 6-day cultures that were pretreated with PSTNm and substrate showed PSA on the GFP-positive neurites of motoneurons as well as on the GFP-negative neurites (see overlay) of cells that differentiated into other neuronal types. Scale bar, 100 μm. D, the PSA-induced spreading of neurites and cells on the dish floor was estimated by measuring the density of GFP fluorescence/surface area (NIH ImageJ 1.45). Like the PST gene, PSTNm/substrate increased the spreading of neurites and cells, and the effect was much higher with the use of both enzymes (one-way ANOVA: p < 0.0001, F = 23.33; Tukey's post-test: *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; error bars: S.E.).

DISCUSSION

The present findings reveal that PSTNm can be employed as a simple and efficient tool to add PSA to the surface of different cell types in culture or in the brain. Previous studies have shown that purified PSTNm is able to synthesize PSA on a variety of proteins having in common a glycomoiety with a minimum of 2 tandem sialic acid residues that serves as the direct acceptor (26, 27). The fact that PSA produced by PSTNm on surfaces of live animal cells is removed by trypsinization suggests that the enzyme also polysialylates membrane-bound proteins. As initiation of PSA synthesis by PSTNm has been shown to require a terminal disialic acid primer (26, 27), it is likely that these proteins bear such a moiety. However, it remains possible that smaller amounts of PSA are added to other disialoacceptors, such as glycolipids.

The natural acceptor(s) for PSTNm in N. meningitidis are as yet undefined. In the bacterium, PSTNm produces PSA at the cytoplasmic face of the inner membrane, after which the polymer is translocated to the outer capsule. Although PSTNm is described here as a therapeutic tool, the remarkable effectiveness of the enzyme in modifying surface proteins of animal cells, together with its activity with a variety of molecules in solution (26, 27), may help to understand its mechanism of action in bacteria as well.

The polysialylation by PSTNm occurs rapidly and persists for a period of weeks in vivo, and is not permanent. It is also biologically active in terms of cell adhesion, cell migration, and axon outgrowth. These characteristics suggest that this procedure can be suitable for therapeutic use of engineered PSA in tissue repair, in addition to providing a new tool for basic studies. Although the majority of PSA produced by PSTNm appears to be attached to surface proteins other than NCAM, the biological activity of this PSA, ranging from simple cell adhesion to quite complex axonal and cell migration behavior, is very similar to that exhibited by endogenous PSA-NCAM. Functional equivalence might seem unlikely for such a simple glycomoiety produced on different membrane anchors. However, it is consistent with the fact that the effects of PSA on cell adhesion do not require the presence of an intact NCAM protein (3) and that its ability to attenuate cell interactions at least in part depends on the steric hindrance produced between apposing cell membranes by its enormous hydrated volume (3, 4). Thus, the present demonstration that PSA has biological activity when produced by a totally foreign synthetic mechanism, mostly on non-NCAM acceptors, provides strong support for the functional importance of the intrinsic biophysical properties of PSA.

The use of injected PSTNm has several potential advantages over viral delivery of the vertebrate polysialyltransferase genes. The relatively rapid and transient nature of this direct synthesis matches well with the time course of cell migration and axon growth in vitro. Moreover, whereas limited viral diffusion in tissues largely restricts genetically induced PSA expression to the vicinity of the injection site, the rapid diffusion of PSTNm and its donor substrate in tissues produces large areas of PSA expression and thus should be more suitable for long range regenerative applications, such as treatment of spinal cord injuries. In addition, multiple injections can be used to extend the duration and extent of polysialylation as needed. PSTNm would add PSA to surface molecules present on most if not all cell surfaces. Given that the effects of PSA are strongest when both apposing cells carry the polymer (34), this feature could be valuable when several distinct cell types or membrane regions are involved in a complex repair process, such as growth of axons through and into a complex mixture of neuronal and glial cells.

Viral introduction of vertebrate PST or STX gene into cultured SCs has proven effective in augmenting their reparative efficacy after transplantation into the lesioned spinal cord (21–24) and has shown promise in improving stem cell-based therapies (18). The cellular basis for these treatments involves cell migration and axon outgrowth, which as shown here can also be augmented by the PSA produced by PSTNm. Thus, it will be possible to compare the genetic and biochemical approaches for PSA production not only with respect to behavioral outcome, but also in terms of distinct cellular changes. In the present study we used stem cell-derived motoneurons to document the cellular activity of PSTNm-generated PSA. Expression of PSA by motoneurons is critical for proper innervation of muscle both during development (35) and during regeneration following lesion of the adult peripheral nerve (36). These findings suggest that the PSTNm approach may also be of value in enhancing growth of motoneuron axons in vivo.

There remain several factors to be considered in the use of PSTNm for therapeutics. Some highly compact tissue structures such as myelinated fiber bundles in the striatum are either not well penetrated by soluble proteins and remain resistant to polysialylation by PSTNm or do not express enough disialylated acceptor molecules. This could be tested by adding Cst-II, a well defined bacterial sialyltransferase which makes the primer for PSTNm in vitro (26, 27). The rate of elimination of PSTNm-induced PSA also appears to be variable among brain regions, possibly reflecting differences in the turnover of polysialylated membrane proteins. Although there were no obvious effects on the animals' health following PSTNm injection, side effects should be carefully evaluated before any therapeutic consideration. However, the relatively weak immune response of the CNS and the transient nature of PSTNm polysialylation suggest that this may not be a major issue.

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Hynek Wichterle (Columbia University) for providing the HB9::GFP mouse embryonic stem cell line.

Footnotes

- PSA

- polysialic acid

- CHO

- Chinese hamster ovary

- EB

- embryoid body

- endo-N

- endoneuraminidase-N

- mESC

- mouse embryonic stem cell

- NCAM

- neural cell adhesion molecule

- PST

- polysialyltransferase ST8SiaIV

- PSTNm

- polysialyltransferase from Neisseria meningitides

- SC

- Schwann cell

- STX

- polysialyltransferase ST8SiaII.

REFERENCES

- 1. Eckhardt M., Mühlenhoff M., Bethe A., Koopman J., Frosch M., Gerardy-Schahn R. (1995) Molecular characterization of eukaryotic polysialyltransferase-1. Nature 373, 715–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Johnson C. P., Fujimoto I., Rutishauser U., Leckband D. E. (2005) Direct evidence that neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) polysialylation increases intermembrane repulsion and abrogates adhesion. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 137–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fujimoto I., Bruses J. L., Rutishauser U. (2001) Regulation of cell adhesion by polysialic acid: effects on cadherin, immunoglobulin cell adhesion molecule, and integrin function and independence from neural cell adhesion molecule binding or signaling activity. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 31745–31751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rutishauser U. (2008) Polysialic acid in the plasticity of the developing and adult vertebrate nervous system. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 26–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Angata K., Huckaby V., Ranscht B., Terskikh A., Marth J. D., Fukuda M. (2007) Polysialic acid-directed migration and differentiation of neural precursors are essential for mouse brain development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 6659–6668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Weinhold B., Seidenfaden R., Röckle I., Mühlenhoff M., Schertzinger F., Conzelmann S., Marth J. D., Gerardy-Schahn R., Hildebrandt H. (2005) Genetic ablation of polysialic acid causes severe neurodevelopmental defects rescued by deletion of the neural cell adhesion molecule. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 42971–42977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tomasiewicz H., Ono K., Yee D., Thompson C., Goridis C., Rutishauser U., Magnuson T. (1993) Genetic deletion of a neural cell adhesion molecule variant (N-CAM-180) produces distinct defects in the central nervous system. Neuron 11, 1163–1174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cremer H., Lange R., Christoph A., Plomann M., Vopper G., Roes J., Brown R., Baldwin S., Kraemer P., Scheff S. (1994) Inactivation of the N-CAM gene in mice results in size reduction of the olfactory bulb and deficits in spatial learning. Nature 367, 455–459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Daston M. M., Bastmeyer M., Rutishauser U., O'Leary D. D. (1996) Spatially restricted increase in polysialic acid enhances corticospinal axon branching related to target recognition and innervation. J. Neurosci. 16, 5488–5497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tang J., Landmesser L., Rutishauser U. (1992) Polysialic acid influences specific pathfinding by avian motoneurons. Neuron 8, 1031–1044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tang J., Rutishauser U., Landmesser L. (1994) Polysialic acid regulates growth cone behavior during sorting of motor axons in the plexus region. Neuron 13, 405–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yin X., Watanabe M., Rutishauser U. (1995) Effect of polysialic acid on the behavior of retinal ganglion cell axons during growth into the optic tract and tectum. Development 121, 3439–3446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Seki T., Rutishauser U. (1998) Removal of polysialic acid-neural cell adhesion molecule induces aberrant mossy fiber innervation and ectopic synaptogenesis in the hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 18, 3757–3766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. El Maarouf A., Rutishauser U. (2003) Removal of polysialic acid induces aberrant pathways, synaptic vesicle distribution, and terminal arborization of retinotectal axons. J. Comp. Neurol. 460, 203–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Theodosis D. T., Rougon G., Poulain D. A. (1991) Retention of embryonic features by an adult neuronal system capable of plasticity: polysialylated neural cell adhesion molecule in the hypothalamo-neurohypophysial system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88, 5494–5498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. El Maarouf A., Rutishauser U. (2005) in Neuroglycobiology (Fukuda M., Rutishauser U., Schnaar R. L., eds) pp. 39–57, Oxford University Press, London [Google Scholar]

- 17. El Maarouf A., Petridis A. K., Rutishauser U. (2006) Use of polysialic acid in repair of the central nervous system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 16989–16994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. El Maarouf A., Rutishauser U. (2010) Use of PSA-NCAM in repair of the central nervous system. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 663, 137–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhang Y., Ghadiri-Sani M., Zhang X., Richardson P. M., Yeh J., Bo X. (2007) Induced expression of polysialic acid in the spinal cord promotes regeneration of sensory axons. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 35, 109–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhang Y., Zhang X., Yeh J., Richardson P., Bo X. (2007) Engineered expression of polysialic acid enhances Purkinje cell axonal regeneration in L1/GAP-43 double transgenic mice. Eur. J. Neurosci. 25, 351–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lavdas A. A., Franceschini I., Dubois-Dalcq M., Matsas R. (2006) Schwann cells genetically engineered to express PSA show enhanced migratory potential without impairment of their myelinating ability in vitro. Glia 53, 868–878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gravvanis A. I., Lavdas A. A., Papalois A., Tsoutsos D. A., Matsas R. (2007) The beneficial effect of genetically engineered Schwann cells with enhanced motility in peripheral nerve regeneration: review. Acta Neurochir. Suppl. 100, 51–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Papastefanaki F., Chen J., Lavdas A. A., Thomaidou D., Schachner M., Matsas R. (2007) Grafts of Schwann cells engineered to express PSA-NCAM promote functional recovery after spinal cord injury. Brain 130, 2159–2174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ghosh M., Tuesta L. M., Puentes R., Patel S., Melendez K., El Maarouf A., Rutishauser U., Pearse D. D. (2012) Extensive cell migration, axon regeneration, and improved function with polysialic acid-modified Schwann cells after spinal cord injury. Glia 60, 979–992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cho J. W., Troy F. A., 2nd (1994) Polysialic acid engineering: synthesis of polysialylated neoglycosphingolipids by using the polysialyltransferase from neuroinvasive Escherichia coli K1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 11427–11431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Willis L. M., Gilbert M., Karwaski M. F., Blanchard M. C., Wakarchuk W. W. (2008) Characterization of the α-2,8-polysialyltransferase from Neisseria meningitidis with synthetic acceptors, and the development of a self-priming polysialyltransferase fusion enzyme. Glycobiology 18, 177–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lindhout T., Iqbal U., Willis L. M., Reid A. N., Li J., Liu X., Moreno M., Wakarchuk W. W. (2011) Site-specific enzymatic polysialylation of therapeutic proteins using bacterial enzymes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 7397–7402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Karwaski M. F., Wakarchuk W. W., Gilbert M. (2002) High-level expression of recombinant Neisseria CMP-sialic acid synthetase in Escherichia coli. Protein Expr. Purif. 25, 237–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Morley T. J., Withers S. G. (2010) Chemoenzymatic synthesis and enzymatic analysis of 8-modified cytidine monophosphate-sialic acid and sialyl lactose derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 9430–9437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wichterle H., Lieberam I., Porter J. A., Jessell T. M. (2002) Directed differentiation of embryonic stem cells into motor neurons. Cell 110, 385–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wichterle H., Peljto M. (2008) Differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells to spinal motor neurons. Curr. Protoc. Stem. Cell Biol. Chapter 1, Unit 1H 1 1–1H 1 9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Li X. J., Hu B. Y., Jones S. A., Zhang Y. S., Lavaute T., Du Z. W., Zhang S. C. (2008) Directed differentiation of ventral spinal progenitors and motor neurons from human embryonic stem cells by small molecules. Stem Cells 26, 886–893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vimr E. R., McCoy R. D., Vollger H. F., Wilkison N. C., Troy F. A. (1984) Use of prokaryotic-derived probes to identify poly(sialic acid) in neonatal neuronal membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 81, 1971–1975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hoffman S., Edelman G. M. (1983) Kinetics of homophilic binding by embryonic and adult forms of the neural cell adhesion molecule. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 80, 5762–5766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rutishauser U., Landmesser L. (1996) Polysialic acid in the vertebrate nervous system: a promoter of plasticity in cell-cell interactions. Trends Neurosci. 19, 422–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Franz C. K., Rutishauser U., Rafuse V. F. (2005) Polysialylated neural cell adhesion molecule is necessary for selective targeting of regenerating motor neurons. J. Neurosci. 25, 2081–2091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]