Background: The protein kinase D (PKD) family is involved in the control of cell motility and proliferation.

Results: PKD1 controls growth of cancer cells through phosphorylation of Snail1 at Ser-11.

Conclusion: Only PKD1, but not PKD2, mediates isoform-specific control of pancreatic cancer cell proliferation through Snail1.

Significance: We demonstrate for the first time isoform-specific control of pancreatic cancer growth by a single phosphorylation of a substrate.

Keywords: Cell Biology, Pancreatic Cancer, Proliferation, Protein Kinase D (PKD), Transcription Factors

Abstract

We here identify protein kinase D1 (PKD1) as a major regulator of anchorage-dependent and -independent growth of cancer cells controlled via the transcription factor Snail1. Using FRET, we demonstrate that PKD1, but not PKD2, efficiently interacts with Snail1 in nuclei. PKD1 phosphorylates Snail1 at Ser-11. There was no change in the nucleocytoplasmic distribution of Snail1 using wild type Snail1 and Ser-11 phosphosite mutants in different tumor cells. Regardless of its phosphorylation status or following co-expression of constitutively active PKD, Snail1 was predominantly localized to cell nuclei. We also identify a novel mechanism of PKD1-mediated regulation of Snail1 transcriptional activity in tumor cells. The interaction of the co-repressors histone deacetylases 1 and 2 as well as lysyl oxidase-like protein 3 with Snail1 was impaired when Snail1 was not phosphorylated at Ser-11, which led to reduced Snail1-associated histone deacetylase activity. Additionally, lysyl oxidase-like protein 3 expression was up-regulated by ectopic PKD1 expression, implying a synergistic regulation of Snail1-driven transcription. Ectopic expression of PKD1 also up-regulated proliferation markers such as Cyclin D1 and Ajuba. Accordingly, Snail1 and its phosphorylation at Ser-11 were required and sufficient to control PKD1-mediated anchorage-independent growth and anchorage-dependent proliferation of different tumor cells. In conclusion, our data show that PKD1 is crucial to support growth of tumor cells via Snail1.

Introduction

The protein kinase D (PKD)3 family of serine/threonine kinases consists of three members: PKD1 (PKCμ), PKD2, and PKD3. They share similar structural features and often phosphorylate the same substrates (1–7). The protein kinase D family has been implicated in the regulation of proliferation of different cells including pancreatic cancer cells (6–11). We have previously identified protein kinase D as a major regulator of cancer cell motility and invasion (2–5). However, it is unclear whether these functions are regulated by all PKD isoforms in a similar fashion and via the same PKD targets or substrates. Therefore, we investigated how PKD1 and PKD2, two PKD isoforms that mediate vital functions in pancreatic tumor growth and angiogenesis, are involved in the regulation of pancreatic cancer cell growth (12–14). We initiated a bioinformatics screening approach using Scansite (15) to identify putative PKD phosphorylation consensus motifs in potentially relevant PKD substrates and identified (in accordance with Du et al. (16)) Snail1 as a putative PKD substrate. Snail1 is an important zinc finger transcription factor controlling the epithelial-mesenchymal transition and tumor growth (17, 18). Snail1 transcriptional activity can be mediated by regulation of protein stability via lysyl oxidase-like proteins (LOXLs) (19, 20). LOXL isoforms 2 and 3 interact with Snail1 to modify critical lysine residues and thereby stabilize the protein (19). Snail1 repressor activity is also modulated by phosphorylation of 6 residues via glycogen synthase kinase 3β, inducing nuclear export and β-Trcp-controlled ubiquitin-dependent degradation (20, 21). Snail1 transcriptional repression is mediated by recruitment of a Sin3A-histone deacetylase 1 and 2 (HDAC1-HDAC2) complex. This interaction is critical for Snail1 repressor function and dependent on the N-terminal SNAG domain of Snail1 (22), which is adjacent to the PKD phosphorylation consensus in the protein. Thus, the aim of this study was to identify how phosphorylation of Snail1 by PKD regulates Snail1 activity, tumor cell growth, and invasive features and to determine whether Snail1 phosphorylation by PKDs is isoform-specific.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture

Panc89 (pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma), Panc1 (pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma), HEK293T, and HeLa cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FCS and penicillin/streptomycin. Panc1 cells were transfected using Turbofect (Fermentas), and siRNAs were transfected using Oligofectamine (Invitrogen). Experiments in HeLa cells were performed using HeLa Monster reagent (Mirus). Panc1, HEK293T, and HeLa cells were acquired from ATCC. Stable Panc89 cells used in this study were described previously (4, 5). For production of lentiviruses, 6 × 106 HEK293T cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Virus supernatants were harvested after 48 h and used for transduction of stable Panc89 cell lines. Cells were subsequently subjected to puromycin selection to generate semistable cell lines used in assays.

Plasmids, Antibodies, and Dye Reagents

GFP-tagged expression constructs for PKD1, PKD1KD (K612W), PKD2-GFP, and PKD2KD-GFP have been described previously (5, 23). Snail1-FLAG and Snail1-GFP constructs (21) were acquired from Addgene. Snail1S11A/S11E-FLAG and Snail1S11A/S11E-GFP mutants were generated by site-directed mutagenesis (QuikChange II kit, Stratagene) using the following primers: Snail1S11A forward, 5′-CTC-GTC-AGG-AAG-CCC-GCC-GAC-CCC-AAT-CGG-AAG; Snail1S11A reverse, 5′-CTT-CCG-ATT-GGG-GTC-GGC-GGG-CTT-CCT-GAC-GAG; Snail1S11E forward, 5′-CTC-GTC-AGG-AAG-CCC-GAG-GAC-CCC-AAT-CGG-AAG; and Snail1S11E reverse, 5′-CTT-CCG-ATT-GGG-GTC-CTC-GGG-CTT-CCT-GAC-GAG. Mutations were verified by sequencing. Short hairpin RNAs against lacz, PKD1, and PKD2 were described previously (4). Ajuba, Snail1, and Cyclin D1 antibodies were acquired from Cell Signaling Technology. Anti-FLAG M2, anti-Actin AC40 and anti-Tubulin were from Sigma-Aldrich. LOXL3 antibodies were purchased from Abnova and Sigma-Aldrich. Anti-GFP antibody was acquired from Roche Applied Science. HDAC1 and HDAC2 antibodies were from Abcam. Quantitative real time PCR (qPCR) primers were obtained from Qiagen. PKD1 C20 antibody was acquired from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. PKD2 antibody was obtained from Calbiochem. Non-target shRNA control (scrambled, shc002), sh_Snail1 1 (NM_005985.2-136s1c1), and sh_Snail1 2 (NM_005985.2-504s1c1) were from Sigma-Aldrich. Immunofluorescence secondary antibodies were purchased from Invitrogen. pMotif antibody was a gift from Peter Storz (Mayo Clinic).

Total Cell Lysates and Co-immunoprecipitation

Total cell lysates and co-immunoprecipitations were performed as described previously (3, 5, 24). In brief, total cell lysates were either prepared by solubilizing cells in radioimmune precipitation assay buffer (50 mm Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.25% deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS plus complete protease and PhosStop inhibitors (Roche Applied Science)) or 2% SDS lysis buffer (10 mm Hepes, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, pH 6.8 plus inhibitors). Lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 10 min. For immunoprecipitation, equal amounts of proteins were incubated with specific antibodies for 1.5 h at 4 °C. Immune complexes were collected with protein G-Sepharose (GE Healthcare) for 30 min at 4 °C and washed three times with lysis buffer (20 mm Tris, pH 7.4, 5 mg MgCl2, 150 mm NaCl, 1% Triton X-100). Precipitated proteins were released by boiling in sample buffer and subjected to SDS-PAGE. The proteins were blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes (Pall Corp., Germany). After blocking with 2% BSA in TBS with Tween 20, blots were probed with specific antibodies. Proteins were visualized by HRP-coupled secondary antibodies using ECL (Thermo Fisher). Quantitative analysis of Western blots was done by measuring integrated band density using NIH ImageJ. Values shown represent -fold change in respect to control.

qPCR

Quantitative real time PCRs were performed in a Bio-Rad iQ5 cycler with SYBR Green. Total RNA was isolated using an RNeasy minikit (Qiagen). We used 400 ng of total RNA for cDNA synthesis. Quantitative real time PCR analysis was performed in three replicas and in at least three independent experiments using qPCR primers for GAPDH (control), LOXL1–3, and Cyclin D2 (Qiagen). Results were calculated using the ΔΔCt method normalized to GAPDH and vector control cells.

Three-dimensional Basement Membrane Extract (BME) Cell Culture

Three-dimensional BME culture was performed by seeding 10,000 cells of stable Panc89 cell lines (4, 5) in BME (growth factor-reduced, phenol red-free; Cultrex, R&D Systems, Trevigen). Tumor cell clusters were documented after 16 days at 10× magnification (see Fig. 8A) or 32 days (see Fig. 8G) at 8× magnification using a Keyance microscope. Diameters of tumor clusters in images were quantified in perpendicular directions for each cluster using spacial calibration of images (NIH ImageJ). For statistical analysis, conditions were compared using frequency distribution histograms. Statistical significance was calculated using two-tailed unpaired Student's t test.

FIGURE 8.

Three-dimensional growth in BME. A, panels A′–C′, 10,000 single cells of stable Panc89 cell lines expressing GFP, PKD1-GFP, and PKD1KD-GFP were seeded in a BME gel and documented in assays after 16 days. The scale bar represents 100 μm. B, PKD1 significantly enhances clusters growth, whereas PKD1KD decreases cluster size. The average diameter of tumor cell clusters was quantified in perpendicular directions for each cluster using spacial calibration of images (for vector, n = 150; for PKD1-GFP, n = 161; and for PKD1KD-GFP, n = 181). The graph depicts average diameters and S.E. of three experiments. C, frequency distribution histograms of structure diameters for vector versus PKD1-GFP. D, frequency distribution histogram of structure diameters for vector versus PKD1KD-GFP. E, Snail1 enhances whereas S11A mutation inhibits proliferation in HeLa cells after 48 h. The combined analysis of three independent proliferation assays was performed with transiently transfected cells expressing vector, Snail1-GFP, and Snail1S11A-GFP. Cells were seeded after 24 h at a density of 5000 cells/well in triplicate replicas in 96-well plates. Cell density was quantified by measuring A550 of crystal violet-stained cells dissolved in methanol at time points T0, T24, and T48 h. The graph depicts the relative mean intensities for the respective cell lines after 24 and 48 h, respectively. Statistical significance was calculated using an unpaired Student's t test. Doubling times were calculated using linear regression (GraphPad Prism). Representative transgene expression is shown in supplemental Fig. 5. F, Panc89 GFP vector cells were transduced with lentiviruses expressing scrambled control shRNA (Sigma-Aldrich) and sh_PKD1 (NM_002742.x-2978s1c1, Sigma-Aldrich). A PKD1 knockdown was probed using a specific anti-PKD1 antibody in semistable cell lines following selection. Blots were reprobed for PKD2 expression, and Actin was used as a loading control. G, semistable Panc89 vector sh_scramble- and sh_PKD1-expressing cells were seeded at 10,000 single cells in BME gel and documented after 32 days. The scale bar represents 100 μm. H, knockdown of PKD1 significantly reduces clusters growth (diameter). The average diameter of tumor cell clusters was quantified in perpendicular directions for sh_scramble (n = 45) and sh_PKD1 (n = 84). The graph depicts average diameters and S.E. of three experiments. Numbers in the graph denote -fold change in percent. I, frequency distribution histogram for knockdown of PKD1 versus scrambled shRNA control. Knockdown of PKD1 significantly reduces cluster sizes in the BME matrix. Error bars in graphs represent S.E.

Immunofluorescence Confocal Microscopy and Acceptor Photobleach Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET)

HeLa cells were transfected with HeLa Monster and seeded at a density of 150,000 cells/well on glass coverslips. After adhesion overnight, cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde at room temperature for 20 min, washed, quenched with 0.1 m glycine, and then permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100. Samples were blocked and stained in PBS supplemented with 5% FCS, 0.05% Tween 20. Primary and secondary Alexa Fluor dye antibodies (Invitrogen) were incubated for 2 h, respectively. Samples were mounted after extensive washing in Fluoromount-G (Southern Biotechnology) and analyzed by a confocal laser scanning microscope (TCS SP5, Leica) equipped with respective 63× Plan Apo oil immersion objectives. Images were acquired in sequential scan mode, and processing was done using NIH ImageJ. Scale bars represent 10 μm. Acceptor photobleach FRET experiments were performed in transiently transfected HeLa cells processed as stated above. FRET measurements were performed by acquiring pre- and postbleach images of donor and acceptor using the Leica acceptor photobleach FRET macro. Thresholded percent FRET values were depicted using a seven-color look-up table. Quantitative FRET analysis was performed by calculating mean FRET efficiency and S.E. for n = 18 cells and two independent conditions (PKD1 versus PKD2). Statistical significance (****, p < 0.0001) was calculated using two-tailed unpaired Student's t test.

Soft Agar Assays

Anchorage-independent growth was measured using soft agar colony formation assays. Stable Panc89 cells expressing the indicated constructs were seeded at 10,000 cells/well in 6-well plates in 0.5% soft agar (Bacto Agar, BD Biosciences) with 0.5% agar bottom layers in three replicate wells per condition and in at least three independent experiments. Colonies were documented at 10× magnification using a Keyance microscope after 13 days (see Fig. 6B) or 10 days, respectively (see Fig. 7, A and B). For transiently transfected Panc1 cells, 50,000 cells/well in 6-well plates were seeded and documented after 6 days (see Fig. 6C). Results were calculated by quantifying the average number of colonies per visual field at 10× or 4× magnification, whereas for transient expression in Panc1 cells, the entire well was counted. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparison post-testing or Student's unpaired t testing.

FIGURE 6.

A, PKD1, as opposed to PKD2, enhances anchorage-independent growth in soft agar experiments. We seeded 10,000 cells of stable Panc89 cell lines expressing GFP, PKD1-GFP, PKD1KD-GFP, PKD2-GFP, and PKD2KD-GFP in triplicate wells in 0.5% soft agar and documented assays after 13 days. A, the graph depicts the average number of colonies and S.E. per visual field documented at 10× magnification for five independent experiments. Statistical significance (****, p < 0.0001) was calculated using a two-tailed unpaired Student's t test. B, panels A′–E′, examples of soft agar colonies documented for quantification. The scale bar represents 100 μm. C, Snail1 expression enhances anchorage-independent growth of Panc1 cells as compared with vector control, whereas Snail1S11A reduces the number of colonies with respect to wild type Snail1. We transiently transfected 50,000 Panc1 cells and subsequently seeded cells in 0.5% soft agar in triplicate wells per assay and in three experiments. Assays were documented after 6 days. The graph depicts the average number of colonies and S.E. per well at 10× magnification. Statistical significance (****, p < 0.0001) was calculated using one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparison post-testing. Representative transgene expression and images of colonies are shown in supplemental Fig. 4, A and B. Error bars in graphs represent S.E.

FIGURE 7.

Snail1 is a necessary and sufficient mediator of PKD1-regulated anchorage-independent growth and proliferation in pancreatic cancer cells. Stable Panc89 cells expressing GFP vector and PKD1-GFP were transduced with lentiviruses expressing non-target shRNA (scrambled; Sigma-Aldrich), sh_Snail1 1 (NM_005985.2-136s1c1, Sigma-Aldrich), and sh_Snail1 2 (NM_005985.2-504s1c1, Sigma-Aldrich) and subjected to antibiotic selection. Then we used 10,000 cells of stable cell lines expressing the respective constructs and shRNAs and seeded cells in triplicate wells in 0.5% soft agar. Assays were documented after 10 days at 4× magnification for colony counting. A, the graph depicts the combined average number of colonies per visual field of three experiments with six images at 4× magnification per well and three replicate wells per experiment. B, exemplary images (panels A′–F′) used for quantification of colony numbers at 4× magnification. The scale bar represents 100 μm. Table 1 displays average differences (%) in colony number between conditions. Statistical significance (****, p < 0.0001) was calculated using one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparison post-testing. C, control blots for knockdown efficacy of endogenous Snail1 with sh_Snail1 1 and 2 in stable Panc89 cells. Snail1 expression levels were probed in 60 μg of total cell lysates using anti-Snail1 antibody. Tubulin was used as a loading control. Error bars in graphs represent S.E.

Cell Proliferation Assays

Cell proliferation assays were performed with transiently transfected HeLa cells. After 24 h, 5000 cells were seeded in 100 μl of standard growth medium in triplicate replicas per condition in 96-well culture plates for time points T0, T24, T48. After adhesion overnight, T0 cells were fixed and stained with crystal violet (0.5% in H2O, 20% (v/v) methanol) for 20 min at room temperature. After extensive washing, plates were dried, and additional plates were processed after 24 and 48 h in the same manner. To quantify cell density, crystal violet was dissolved in 100 μl of methanol/well, and adsorption was measured at 550 nm using a Tecan1000 plate reader. Doubling time was calculated using linear regression (Prism software). Cell densities in graphs are shown for mean A550 values in triplicate replicas ±S.E.

HDAC Activity Assays

HDAC activity assays were performed using a fluorometric kit (Cayman Chemical Co.). 3 × 106 HeLa cells were seeded in 10-cm dishes with two dishes per condition. Cells were lysed after 48 h according to the manufacturer's instructions. Assays were performed in black 96-well plates in triplicate replicas per condition. To measure HDAC activity, 10 μl of crude nuclear extract were used after normalization of protein content by a BCA kit. Deacetylation of a specific HDAC substrate was measured at 455 nm (excitation, 360 nm) using a Tecan M1000 reader. Assays were further normalized for GFP transgene expression in crude nuclear extracts (Snail1-GFP and Snail1S11A-GFP) by measuring GFP fluorescence at 535 nm (excitation, 475 nm). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparison post-testing.

Statistic Analyses

Statistical analysis was performed using Prism software version 5.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Statistical significance in graphs is indicated by asterisks (*, p = 0.05 to 0.01; **, p = 0.01 to 0.001; ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001).

RESULTS

Following a bioinformatics screen, we identified (in accordance with Ref. 16) Snail1 as a putative PKD substrate and mapped the respective phosphorylation site to Ser-11.

Mapping of PKD1 Phosphorylation Sites in Snail1

Fig. 1A depicts a structural overview of Snail1 with the putative PKD phosphorylation site located at Ser-11 directly adjacent to its SNAG domain (amino acids 1–9). The potential phosphorylation site LVRKPS* matches the published PKD phosphorylation consensus sequence LXRXXS* and partially matches the PKD phosphosubstrate antibody recognition sequence (pMotif; LXR(Q/K/E/M)(M/L/K/E/Q/A)S*) (25, 26). Using anti-pMotif antibody, we investigated Snail1 in vivo phosphorylation by PKD1 (Fig. 1B). Active PKD1 enhanced phosphorylation of Snail1, whereas Snail1 phosphorylation was barely detectable in cells expressing catalytically inactive PKD1KD. In addition, phosphorylation of Snail1 was absent when Ser-11 was replaced by Ala (S11A) even in the presence of active PKD1. Thus, in accordance with data published by Du et al. (16), Ser-11 is a PKD phosphorylation site in vivo, and it is the only PKD phosphorylation site in Snail1 (Fig. 1B). Next, we wanted to assess the upstream regulation of Snail1 by PKD isoforms 1 and 2. To determine whether both isoforms would interact with Snail1 in intact cells, we performed co-localization and FRET studies.

FIGURE 1.

Mapping of PKD phosphorylation sites in Snail1 in vivo. A, structural overview of Snail1. The N-terminal SNAG domain, serine-proline-rich region, destruction box, nuclear export sequence (NES), and C2H2 zinc fingers are shown. The putative PKD phosphorylation consensus motif of Snail1 Ser-11 and the consensus sequence of the phospho-PKD substrate motif antibody (pMotif) are shown below the graph. B, mapping of Snail1 phosphorylation at Ser-11 in vivo. Blots depict immunoprecipitates (IP) of FLAG-Snail1 from HeLa cells co-expressing Snail1-FLAG and Snail1S11A-FLAG constructs with active (CA) and kinase-inactive (KD) PKD1. Control blots on the right-hand side display transgene expression. Phosphorylation of Snail1 at Ser-11 was probed using pMotif antibody and reprobed with anti-FLAG M2. endogen, endogenous.

Only PKD1 Interacts Efficiently with Snail1 in the Nuclei of HeLa Cells

For co-localization and FRET studies, we used transiently transfected HeLa cells ectopically expressing Snail1-FLAG together with PKD1-GFP or PKD2-GFP, respectively. Both PKD1 and -2 were localized to nuclei of HeLa cells and co-localized with FLAG-tagged Snail1 (Fig. 2, A and B). To further characterize this co-localization and to determine a potential interaction, we performed acceptor photobleach FRET studies. Fig. 2A displays a representative FRET experiment for PKD1-GFP and Snail1-FLAG. Panels A′ and B′ depict donor pre- and postbleach states, whereas panels D′ and E′ show acceptor pre- and postbleach images, respectively. The relative increase in donor fluorescence intensity is marked by arrowheads in postbleach images (panel B′). Percent FRET values indicating interaction of the two proteins are shown in panel F′ depicted by a seven-color look-up table (Fig. 2A, panels A′–F′). Similar experiments were performed for PKD2-GFP and Snail1-FLAG (Fig. 2B, panels A′–F′). Active PKD2 is known to phosphorylate nuclear substrates (27). However, interaction of wild type PKD2 and Snail1 was barely detectable. Fig. 2C displays the statistical analysis of mean FRET efficiency and S.E. for PKD1-GFP (n = 18) and for PKD2-GFP (n = 17) cells. Mean FRET efficiency dropped markedly by 3.38-fold for PKD2 (3.8 ± 1.1%) as compared with PKD1 (12.9 ± 1.1%) with some cells displaying no interaction at all (Fig. 2B). (FRET efficiency values for all experiments are shown in supplemental Table 2.) These data indicate that PKD1 preferably interacts with Snail1 and suggests that interaction between PKDs and Snail1 is isoform-specific. We further verified these findings by co-precipitation experiments with endogenous Snail1 and PKD1 (Fig. 2D).

FIGURE 2.

PKD1- and PKD2-GFP co-localize with Snail1-FLAG in nuclei of HeLa cells. Only PKD1-GFP is capable of efficiently interacting with Snail1-FLAG in nuclei, whereas interaction efficiency is significantly reduced by 3.38 times for PKD2. A, panels A′–F′, acceptor photobleach FRET experiment in HeLa cells co-expressing PKD1-GFP and Snail1-FLAG labeled with anti-FLAG M2 and Alexa Fluor 546 antibodies. Panels A′ and B′ depict donor pre- and postbleach, whereas panels D′ and E′ display acceptor pre- and postbleach states, respectively. Bleached regions of interest (ROIs) are shown in panel C′. Percent FRET values are depicted in panel F′, and FRET is represented by a thresholded seven-color look-up table (LUT). B, acceptor photobleach FRET experiment in HeLa cells co-expressing PKD2-GFP and Snail1-FLAG. Panels A′ and B′) depict donor pre- and postbleach, whereas panels D′ and E′ display acceptor pre- and postbleach states, respectively. Bleached regions of interest are shown in panel C′. Percent FRET values are depicted in panel F′. Images shown are of a single confocal section. The scale bar represents 10 μm. C, statistical analysis of acceptor photobleach FRET experiments displayed in A and B. The graph depicts mean FRET efficiency and S.E. for PKD1 (n = 18 cells) and PKD2-GFP (n = 17 cells) experiments. FRET efficiency values for all experiments are shown in supplemental Table 2. Statistical significance (****, p < 0.0001) was calculated using a two-tailed unpaired Student's t test. D, endogenous Snail1 and PKD1 interact. Anti-PKD1 and nonspecific IgGs were used for immunoprecipitation (IP) from Panc89 vector cells. Immunoprecipitations were subsequently probed for the presence of endogenous Snail1 using specific antibodies. Error bars in graphs represent S.E.

Du et al. (16) reported that phosphorylation of Snail1 at Ser-11 by PKDs regulates its nuclear export by interaction with 14-3-3σ proteins in epithelial cell lines including C4-2 tumor cells. However, the authors conceded that tumor cells may have different mechanisms for regulating Snail1 transcriptional activity. We investigated how subcellular localization of Snail1 was altered when Ser-11 was phosphorylated by PKD1 in two epithelial cancer cell lines, Panc1 human pancreatic cancer cells and HeLa cervical cancer cells.

Subcellular Localization of Snail1, Snail1S11A, and Snail1S11E Is Not Changed

To first investigate how Snail1 phosphorylation would impact its subcellular localization, we performed localization studies with Snail1 and the S11A and S11E phosphosite mutants in HeLa and Panc1 cells, respectively. There was no detectable change in subcellular localization using the phosphosite mutants compared with Snail1 wild type (WT) in HeLa cells (Fig. 3A) and Panc1 cells (data not shown). We quantified subcellular distribution in three experiments using HeLa cells and found that Snail1 predominantly localized in nuclei independently of its phosphorylation status in more than 99% of at least 1000 cells quantified per condition (Fig. 3A, panels A′–O′). We also did not observe any change in the subcellular localization of wild type Snail1 upon co-expression with constitutively active PKD1 in both HeLa (Fig. 3B) and Panc1 cells (data not shown). Similar data were obtained with endogenous Snail1 in both cell lines expressing active PKD1 (supplemental Fig. 1A). In addition, there was no change in the subcellular localization of predominantly cytoplasmic endogenous Snail1 in non-transformed, immortalized HEK293T cells upon expression of active PKD1 or kinase-inactive PKD1KD (supplemental Fig. 1B). According to Du et al. (16), Snail1 should have exhibited nuclear localization in cells expressing PKD1KD in this setting. Thus, in the cell lines examined in this study, 14-3-3σ binding to a consensus surrounding Ser-11 does not seem to be the relevant mechanism for Snail1 subcellular localization. This prompted us to investigate further molecular mechanisms to explain the function of Snail1 phosphorylation by PKD1.

FIGURE 3.

Phosphorylation of Ser-11 by PKD does not alter subcellular distribution of Snail1. A, Snail1-GFP (panels A′–E′), Snail1S11A-GFP (panels F′–J′), and Snail1S11E-GFP (panels K′–O′) are predominantly localized to the nucleus independently of Snail1 Ser-11 mutation status. B, co-expression of constitutively active PKD1.CA-GFP (A′) with wild type Snail1-FLAG (B′ and E′) does not alter subcellular localization of Snail1 (A′–E′). Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Images depict single confocal sections. The scale bar represents 10 μm.

Regulation of Snail1-mediated Transcriptional Activity by Lysyl Oxidase-like Family Members 2 and 3

In addition to HDAC1 and -2 (22), LOXL2 and -3 are known Snail1 interaction partners, enhancing Snail1 protein stability and Snail1-dependent regulation of marker genes (19). To investigate their role in the regulation of Snail1 transcriptional activity downstream of PKD1, we initially screened a panel of pancreatic cancer cell lines including Panc89 cells stably expressing GFP vector or PKD1-GFP (4, 5) as well as HeLa cells for the presence of Snail1, PKD1, and the LOXL3 isoform (Fig. 4A). Snail1 and LOXL3 proteins were present in HeLa, Panc1, MiaPaca, Panc89, and the stable Panc89 cell lines. PKD1 was expressed at different levels in all cell lines. Snail1 was strongly expressed in HeLa, Panc1, and both stable Panc89 cell lines, prompting us to use these cells for further analyses. Using qPCR, we additionally tested which LOXL isoforms were present in these stable Panc89 GFP vector or PKD1-GFP cells and whether a further upstream regulation by PKD1 may be involved. Both LOXL2 and -3 isoforms were expressed in Panc89 cells. To our surprise, the expression of LOXL3, but not of LOXL2, was significantly up-regulated by 5.5 ± 0.36-fold in cells expressing PKD1 (Fig. 4, B and C), suggesting a PKD1-dependent synergistic regulation of Snail1 activity via LOXL3. Next, we investigated how phosphorylation at Ser-11 would impact co-regulation by HDACs. Thus, we initially performed co-localization studies of WT Snail1 and Snail1-S11A with the published co-regulator HDAC1 (22) in HeLa cells. Both Snail1-FLAG and Snail1S11A-FLAG co-localized with the endogenous co-repressor HDAC1 in the nuclei (Fig. 4D). We were further able to demonstrate interaction of Snail1-FLAG with HDAC1 in the nuclei by acceptor photobleach FRET (data not shown).

FIGURE 4.

A, Snail1, LOXL3, and PKD1 are expressed in a subset of pancreatic cancer cell lines, HeLa cells, and stable Panc89 cells expressing GFP vector as well as PKD1-GFP. 200 μg of total cell lysates were probed with specific antibodies. B, expression and upstream regulation of the Snail1 co-regulator lysyl oxidase-like proteins 2 and 3 in stable Panc89 cell lines. LOXL3, but not LOXL2, is up-regulated by ectopic PKD1. The graph displays -fold change in regulation relative to respective vector controls. qPCR for LOXL2 and LOXL3 was performed on RNA isolated from stable Panc89 cells expressing GFP and PKD1-GFP. Four independent experiments were quantified in triplicate replicas. Results were normalized to GAPDH and calculated according to the ΔΔCt method. Statistical significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple comparison post-testing (***, p < 0.05). C, LOXL3 expression is up-regulated in stable PKD1-GFP Panc89 cells. 250 μg of total cell lysates were probed for LOXL3 using specific antibodies. D, regulation of Snail1 activity by phosphorylation at Ser-11. Co-localization of Snail1-FLAG (panels A′–C′) and Snail1S11A-FLAG (panels D′ and E′) with their endogenous co-repressor HDAC1 in HeLa nuclei is shown. Images depict single confocal sections. The scale bar represents 10 μm. E, mutation Snail1S11A impairs interaction of Snail1 with co-expressed FLAG-HDAC2, whereas binding is reconstituted with Snail1S11E. Proteins were probed with respective specific antibodies in Western blots. F, statistical analysis of three independent co-precipitation experiments in E. -Fold change in HDAC2 co-precipitation with Snail1 and mutants was calculated from integrated band densities of Western blots. Significance was calculated using Student's t test. G, co-immunoprecipitation (IP) of endogenous HDAC1 with Snail1-, Snail1S11A-, and Snail1S11E-GFP from HeLa total cell lysates. Endogenous HDAC1 was probed with specific antibodies, and immunoprecipitations were reprobed for Snail1 expression by anti-Snail1 antibody. H, co-immunoprecipitation of endogenous HDAC2 with Snail1-, Snail1S11A-, and Snail1S11E-GFP in HeLa total cell lysates. Endogenous HDAC2 was probed with specific antibodies, and immunoprecipitations were reprobed for Snail1 expression. Error bars in graphs represent S.E.

Binding of HDAC1, HDAC2, and LOXL3 Is Impaired by Snail1S11A, Reducing HDAC Activity

To study the molecular impact on HDAC binding following phosphorylation of Ser-11, we performed co-immunoprecipitation studies with phosphosite mutants. The Snail co-repressors HDAC1 and -2 interact with Snail1 in transcriptional complexes to regulate the expression of target genes (22). LOXL2 and -3 isoforms also act as co-regulators, modifying Snail1-mediated transcriptional regulation by enhancing its stability. The interaction of LOXL2 with Snail1 has been shown to be dependent on the N-terminal part of Snail1, which contains the SNAG domain (amino acids 1–9) adjacent to the Ser-11 phosphorylation site, and this part is also essential for interaction with HDAC transcriptional co-repressors (19, 28). Thus, we performed co-immunoprecipitation experiments in HeLa cells following co-expression of FLAG-tagged HDACs with Snail1 phosphosite mutants as well as with endogenous HDAC1 and -2 (22). Strikingly, the interaction of both HDAC1 (data not shown) and -2 with Snail1 was decreased upon expression of the Snail1S11A mutant but not upon expression of SnailS11E (Fig. 4E). Fig. 4F depicts the result of three independent co-immunoprecipitation experiments for co-expressed HDAC2. HDAC2 binding was significantly reduced with the S11A mutant and almost returned to the wild type level with S11E. HDAC1 demonstrated the same overall pattern of regulation (data not shown). We also investigated the interaction of endogenous HDACs with wild type Snail1 as well as its S11A and S11E mutant proteins. Fig. 4, G and H, show that binding of endogenous HDAC1 and HDAC2 to Snail1S11A was reduced as compared with wild type Snail1 from 1 to 0.53 times integrated band density for HDAC1 and to 0.58 times for HDAC2, whereas it was increased for the S11E mutant to 1.29 times for HDAC1 and 1.24 times for HDAC2. Additional co-immunoprecipitation experiments with endogenous HDAC1 and -2 also using other tags may be found in supplemental Fig. 2, A–D. Thus, phosphorylation of Snail1 Ser-11 by PKD1 is likely to be required for the stable interaction with its co-repressors (Fig. 4, E–H). In accordance with these data, LOXL3 interaction with Snail1S11A was also decreased as observed in co-immunoprecipitation experiments. Integrated band densities were reduced from 1 for WT to 0.3 times for the Snail1S11A mutant (supplemental Fig. 2E). We next assessed how the phosphorylation-dependent interaction of Snail1 with its co-regulators modulates HDAC transcriptional regulatory activity.

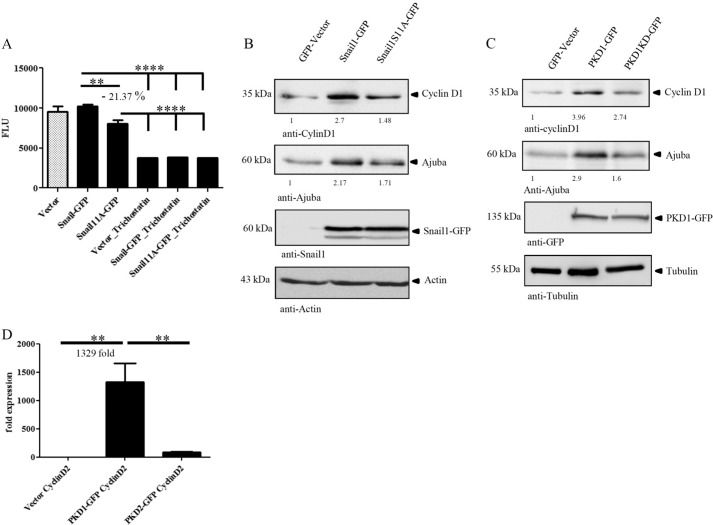

Snail1-dependent HDAC Activity and Regulation of Proliferation Markers

We performed HDAC activity assays measuring WT Snail1- as well as Snail1S11A-associated histone deacetylation to verify results of co-immunoprecipitation experiments. GFP vector, Snail1-GFP, or Snail1S11A-GFP constructs were ectopically expressed in HeLa cells for 48 h, and crude nuclear extracts were prepared using an HDAC activity assay kit (Cayman Chemical Co.). Equal amounts of extract were used in assays, and results were further normalized to GFP-Snail1 transgene expression present in nuclear lysates. In line with interaction studies, statistical analysis of three independent HDAC assays demonstrated reduced activity in cells expressing the Snail1S11A mutant by 21.37% compared with WT Snail1 (Fig. 5A). Expression of Snail1 transgene controls in crude nuclear lysates is shown in supplemental Fig. 3A. Because Snail1-associated HDAC activity contributes only partially to the total HDAC activity as demonstrated by inhibition with the HDAC inhibitor trichostatin (Fig. 5A), the extent of activity reduction by the S11A mutant is remarkable and also matches the markedly reduced HDAC1/2 and LOXL3 binding (Fig. 4, E–H, and supplemental Fig. 2E). Because we were interested in the role of Snail1 in the control of pancreatic cancer growth, we next investigated whether HDAC activity also translated into expression of marker proteins known to be involved in proliferation (Fig. 5, B and C). Thus, we investigated proliferation markers regulated downstream of Snail1 and PKD1 in Panc1 and the stable Panc89 cell lines. Panc1 cells were transiently transfected with GFP vector, Snail1-GFP, or Snail1S11A-GFP and changes in Cyclin D1 expression levels were observed (29–31). Cyclin D1 was markedly up-regulated by Snail1-GFP, whereas expression of Snail1S11A reduced Cyclin D1 expression (vector, 1-fold; Snail1-GFP, 2.7-fold; Snail1S11A-GFP, 1.48-fold integrated band density; Fig. 4B). We further tested the effects of the phosphomimetic Snail1S11E mutant on Cyclin D1 expression. Indeed, Cyclin D1 was markedly up-regulated by Snail1S11E (supplemental Fig. 3B). To substantiate our findings, we additionally investigated a second proliferation marker, Ajuba. Interestingly, we found Ajuba to be a downstream target of Snail1. Ajuba is known to regulate cell cycle progression and G2/M transition by enhancing Aurora A kinase activity through direct interaction (32–34). Thus, Ajuba is involved in mitotic checkpoint control (34). Additionally, Aurora A and B kinases are overexpressed in cancer tissues and are potentially tumorigenic (32). Ajuba protein levels were up-regulated by WT Snail1, whereas its expression was reduced by Snail1S11A (vector, 1-fold; Snail1-GFP, 2.22-fold; Snail1S11A-GFP, 1.78-fold integrated band density; Fig. 5B). To further validate our results, we assessed the regulation of the same markers in Panc89 cells stably expressing either vector, PKD1-GFP, or kinase-inactive PKD1KD-GFP (Fig. 5C). In line with Fig. 5B, Cyclin D1 was up-regulated 3.9-fold by PKD1-GFP, whereas its expression dropped 2.74-fold upon expression of PKD1KD-GFP. The expression of Ajuba was up-regulated by PKD1-GFP 2.9-fold compared with only 1.6-fold by PKD1KD-GFP. Thus, PKD1-mediated regulation of proliferation markers is similar to that of Snail1 and its phosphosite mutants. However, PKD1KD-GFP was not capable to act fully as a dominant negative construct in these experiments. This may be explained in line with the literature (23) by a prominent localization of PKD1KD-GFP at the trans-Golgi network as evidenced by strong co-localization with trans-Golgi network marker TGN46 (supplemental Fig. 3C).

FIGURE 5.

Snail1-dependent histone deacetylase activity and regulation of proliferation markers. A, Snail1S11A reduces Snail1-associated HDAC activity as compared with wild type Snail1. HDAC activity was measured using a fluorometric assay kit. Crude nuclear extracts from 10 × 106 HeLa nuclei were normalized for protein expression, and HDAC activity was measured in triplicate wells per condition in 96-well plates (Tecan infinity M1000) for GFP vector, Snail1-GFP, and Snail1S11A-GFP. For Snail1-GFP and Snail1S11A-GFP, results were further normalized to GFP transgene expression levels in crude lysates. The graph depicts the combined statistical analysis of three experiments. Statistical significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparison post-testing. Expression of transgenes in HeLa crude nuclear extracts and loading controls are shown in supplemental Fig. 3C. B, Snail1S11A impairs Snail1-mediated proliferation marker protein expression in Panc1 cells. Panc1 cells were transfected with GFP, Snail1-GFP, and Snail1S11A-GFP. Cyclin D1 and Ajuba markers involved in the regulation of proliferation were probed in 60 μg of total cell lysates with specific antibodies. Transgenes were probed with anti-Snail1 antibody. Actin was used as a loading control. C, PKD1 and PKD1KD-GFP regulate proliferation marker protein levels in a pattern similar to that of phosphosite mutants. The expression levels of Cyclin D1 and Ajuba were probed with respective antibodies in 60 μg of total cell lysates of stable Panc89 cells. Transgenes were detected with anti-GFP antibody. Tubulin was used as a loading control. D, expression of the Snail target gene Cyclin D2 is prominently up-regulated by ectopic PKD1, but not PKD2 expression. The graph displays fold change in regulation relative to respective vector controls. Quantitative real-time PCR for Cyclin D2 was performed on RNA isolated from stable Panc89 cells expressing GFP, PKD1-GFP, and PKD2-GFP. Four independent experiments were quantified in triplicate replica. Results were normalized to GAPDH and calculated according to the ΔΔCT-method. Statistical significance (**, p < 0.05) was calculated using one-way Anova with Bonferroni multiple comparison post-testing. Error bars in graphs represent S.E.

To further assess whether the regulation of downstream targets by PKDs was indeed isoform-specific, we examined the regulation of another Snail target, Cyclin D2 (18), by qPCR in Panc89 cells expressing PKD1- or PKD2-GFP, respectively. In line with our previous findings, Cyclin D2 expression was up-regulated 1329-fold by wild type PKD1, whereas its expression was only up-regulated 90.8-fold by wild type PKD2, only 7% of the effect of PKD1. These data confirm the selective regulation of Cyclin D2 by PKD1 as compared with PKD2 (Fig. 5D).

We next investigated whether these biochemical data would translate into biological readouts. At first, soft agar assays were performed to identify changes in anchorage-independent growth mediated by PKD1 and -2 isoforms or the respective kinase-inactive proteins.

PKD1, but Not PKD2, Enhances Anchorage-independent Growth in Panc89 Cells

Fig. 6A shows the statistical analysis of five independent soft agar experiments performed with Panc89 cells stably expressing GFP vector, PKD1-GFP, kinase-inactive PKD1 (PKD1KD-GFP), PKD2-GFP, or kinase-inactive PKD2 (PKD2KD-GFP), respectively (4, 5). In line with our FRET studies and the biochemical data shown above, only wild type PKD1 significantly increased the average number of colonies per visual field by 31.4 times as compared with GFP vector cells. PKD1KD reduced the number of colonies as compared with PKD1-GFP by 3.6 times but still had a minor effect on anchorage-independent growth of Panc89 cells, which correlates well with the data on proliferation marker expression (Fig. 5B). In contrast, PKD2 had no effect on anchorage-independent growth (Fig. 6, A and B, panels D′ and E′). Fig. 6B, panels A′–E′, show representative colonies documented for quantification. In addition to the significant increase in colony number, colony size was also markedly increased upon expression of PKD1 (Fig. 6B, panel B′). Thus, our results again indicate a PKD1 isoform-specific regulation of anchorage-independent proliferation in pancreatic cancer cells. We additionally performed soft agar experiments with transiently transfected Panc1 cells expressing GFP vector, WT Snail1-GFP, and the S11A mutant construct (Fig. 6C). In line with previous experiments performed with PKD1, anchorage-independent growth in Panc1 cells was significantly enhanced by WT Snail1 (3.65 times) as compared with vector control (****, p < 0.0001) and reduced by 44% upon expression of the S11A mutant compared with WT Snail1 (****, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 6C). Colonies documented for the respective conditions are depicted in supplemental Fig. 4A (panels A′–C′), and transgene expression of total cell lysates is shown in supplemental Fig. 4B.

Snail1 Is Required to Mediate PKD1-regulated Effects on Anchorage-independent Growth

To demonstrate that PKD1-mediated Snail1 phosphorylation is required for PKD1-induced anchorage-independent growth of pancreatic cancer cells, we performed soft agar assays with Panc89 cells stably expressing vector or PKD1-GFP with two different shRNAs against Snail1 as well as a non-targeting scrambled control. Fig. 7A displays the summarized statistical analysis of three soft agar assays with Panc89 cells. PKD1 expression increased anchorage-independent growth as compared with vector cells by 84.6%. In vector cells, knockdown of Snail1 reduced the average number of colonies per visual field by 60.4% for sh_Snail1 1 and 53.6% for sh_Snail1 2. For PKD1-expressing cells, Snail1 knockdown reduced the number of colonies by 68.5% for sh_Snail1 1 and 82.8% for sh_Snail1 2 (Table 1). We also quantified colony size. PKD1 expression enhanced colony size, and this was reduced by knockdown of Snail1 (data not shown). Examples of images used for quantification of colony numbers at 4× magnification are shown in Fig. 7B for all conditions (panels A′–F′). The respective knockdown controls for Snail1 in the stable cell lines are shown in Fig. 7C. In conclusion, these data indicate that Snail1 as a downstream target of PKD1 is required to regulate anchorage-independent growth of pancreatic cancer cells by Ser-11 phosphorylation.

TABLE 1.

Regulation of anchorage-independent growth by PKD1 and Snail1 shRNAs

Relative differences (%) in colony numbers are indicated by positive and negative values, respectively.

| Colonies | +/−Change |

|---|---|

| % | |

| Vector_sh_scramble to PKD1-GFP_sh_scramble | +84.6 |

| Vector_sh_scramble to Vector_sh_Snail1 1 | −60.4 |

| Vector_sh_scramble to Vector_sh_Snail1 2 | −53.6 |

| PKD1-GFP_sh_scramble to PKD1-GFP_sh_Snail1 1 | −68.5 |

| PKD1-GFP_sh_scramble to PKD1-GFP_sh_Snail1 2 | −82.8 |

PKD1 Enhances Whereas PKD1KD Inhibits Panc89 Tumor Cluster Growth in Three-dimensional BME Culture

To investigate a PKD1-dependent regulation of anchorage-dependent tumor cluster growth and proliferation, we performed three-dimensional BME culture using stable Panc89 cells expressing PKD1- and PKD1KD-GFP. Vector, PKD1-GFP, and PKD1KD-GFP cells were seeded in BME and documented after 16 days of growth. Fig. 8A displays representative examples of tumor cell clusters used for the assessment of three-dimensional growth (diameter). In line with the soft agar assays, the average size of tumor cell clusters with stable ectopic expression of PKD1-GFP was significantly increased by 10.1% as compared with GFP vector-expressing cells (***, p < 0.0005) (Fig. 8, A and B). PKD1KD-GFP significantly reduced the average cluster diameters by 10.3% when compared with vector controls (****, p < 0.0001) (Fig. 8B), indicating that PKD1 is also involved in the regulation of anchorage-dependent growth of pancreatic tumor cell clusters. Fig. 8, C and D, depict the respective frequency distribution histograms of tumor cluster diameters for PKD1-GFP and PKD1KD compared with GFP control cells. These data demonstrate that PKD1 expression resulted in a higher percentage of larger clusters, whereas PKD1KD-expressing cells formed smaller colonies. To corroborate these data, we performed proliferation assays with HeLa cells to investigate a general regulation of anchorage-dependent proliferation by Snail1 Ser-11 phosphorylation. GFP vector, WT Snail1, and the Snail1S11A mutant were transiently expressed in HeLa cells, and proliferation was quantified by measuring A550 values of crystal violet-stained cells at time points T0, T24, and T48 h. 48 h after transfection WT Snail1 markedly decreased doubling times from 56.25 to 35.65 h (vector versus Snail1-GFP), enhancing proliferation, whereas expression of Snail1S11A had virtually no effect on the doubling time (52.17 h) (Fig. 8E). Transgene expression is shown in supplemental Fig. 5. Thus, PKD1-dependent phosphorylation of Snail1 at Ser-11 is involved in controlling anchorage-dependent and -independent growth and proliferation in two-dimensional and three-dimensional environments. To further validate our data on the regulation of proliferation by PKD1, we performed lentivirus-mediated knockdown experiments in GFP vector cells followed by three-dimensional BME culture (Fig. 8, F–H). Clusters were documented after 32 days (Fig. 8G). In line with all previous data, knockdown of PKD1 resulted in drastically reduced cluster sizes (diameters) of 38.3% in PKD1 knockdown cells (Fig. 8H). Specific knockdown of PKD1, but not PKD2, was verified by isoform-specific antibodies (Fig. 8F). Frequency distribution histograms show a shift to smaller cluster diameters following knockdown of PKD1 (Fig. 8I). Taken together, these findings indicate that PKD1 enhances proliferation and anchorage-dependent growth of tumor cell clusters in three-dimensional culture. By contrast, PKD1KD-GFP or knockdown of PKD1 significantly inhibited proliferation, and this was mediated by phosphorylation of Snail1 at Ser-11.

DISCUSSION

PKDs are involved in the regulation of important cellular features such as proliferation (10, 11, 13, 35–37), motility, and invasiveness (2–5) of different tumor types. However, specific and detailed functions for distinct PKD isoforms have not been addressed so far. In a previous work, Ochi et al. (38) have proposed a function for PKD1 in the regulation of anchorage-dependent growth. However, the properties of distinct PKD isoforms were not directly compared or addressed by inhibitors that are not isoform-specific. Thus, it is as yet unclear whether PKD isoforms act in a redundant or specific fashion in tumors.

Our findings indicate that PKD1, as opposed to PKD2, regulates the expression of marker proteins involved in a hyperproliferative phenotype such as Cyclins D1 and D2 (29, 31) as well as Ajuba (33, 34) via phosphorylation of Snail1 at serine 11 in pancreatic cancer cells. Our data also suggest that phosphorylation at this site is necessary for efficient binding of vital Snail1 co-repressors such as HDAC2 modulating Snail1-dependent HDAC activity. In contrast to Du et al. (16), Snail1 phosphorylation at Ser-11 did not affect nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of the protein. This may be explained by 14-3-3σ down-regulation in many tumor cells by different mechanisms (39) including promotor methylation and inhibition downstream of p53 mutations, thereby facilitating cancer formation by many routes (40). Indeed, PKD1KD was not able to induce nuclear localization of primarily cytoplasmic Snail1 in non-transformed, immortalized HEK293T cells (supplemental Fig. 1B). Here we propose a different mechanism for the regulation of Snail1 function by PKD1 in tumor cells: the phosphorylation-dependent binding of co-repressors such as HDAC2 to Snail1. In addition to regulation of HDAC activity, we identified another regulatory mechanism induced by PKD1 that affects Snail1 function: PKD1 is required for up-regulation of LOXL3, which can stabilize the Snail1 protein (Fig. 4, A, B, and C, and supplemental Fig. 2E).

In conclusion, our data demonstrate that PKD1 enhances proliferation (10, 36) of pancreatic and other cancer cells, and this regulation is mediated by Snail1 via phosphorylation at Ser-11. Snail1 is therefore required and sufficient for PKD1-driven proliferation and anchorage-independent growth of different tumor cells. An overview of PKD1-mediated Snail1 regulation and control of biological effects is depicted in Fig. 9.

FIGURE 9.

Overview of PKD1-mediated Snail1 regulation. PKD1 phosphorylation of Snail1 Ser-11 is necessary for efficient binding of co-repressors HDAC1 and -2 as well as LOXL3. Expression of LOXL3, acting as a functional transcriptional co-activator, is also up-regulated by PKD1, implying a positive synergistic activation of Snail1. Snail1 phosphorylation at Ser-11 by PKD1 enhances Snail1 marker protein expression involved in proliferation and anchorage-independent growth. This regulation is necessary as well as sufficient to modulate hyperproliferation in Panc89 pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cells and other cell lines. 2D, two-dimensional; 3D, three-dimensional.

Thus, PKD1 expression could be relevant for primary tumors to drive proliferation and initiate epithelial-mesenchymal transition, preparing cells for the dissemination phase. At later stages, however, when cells are invading the surrounding matrix or tumor stroma, loss of PKD1 activity could even be beneficial because loss of PKD1 enables cells to acquire a high motility phenotype via the regulation of Actin-regulatory proteins such as Cortactin and Slingshot1L. This is also further supported by reports showing a reduced expression of PKD1 in a number of invasive tumor cells and tumor tissues (2).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. A. Hausser (University of Stuttgart) for providing PKD1 and -2 expression constructs. We thank Professor Peter Scheurich (University of Stuttgart) and the University of Halle Cell Sorting Core facility for sorting of stable Panc89 cell lines.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants R01CA140182 and R01GM86435 (to P. S.). This work was also supported by Deutsche Krebshilfe Grant 109222, Wilhelm-Roux-Program Grants FKZ 23/19 and FKZ 23/08 (to T. E.), Florida Department of Health Bankhead-Coley Cancer Research Program Grant FLA07BN-08 (to P. S.), and German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung) Grant NGFN plus/PKB-01GS08209-4 (to T. S.).

This article contains supplemental Figs. 1–5 and Table 2.

- PKD

- protein kinase D

- LOXL

- lysyl oxidase-like protein

- KD

- kinase-dead

- qPCR

- quantitative real time PCR

- BME

- basement membrane extract

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance

- HDAC

- histone deacetylase.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lint J. V., Rykx A., Vantus T., Vandenheede J. R. (2002) Getting to know protein kinase D. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 34, 577–581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Eiseler T., Döppler H., Yan I. K., Goodison S., Storz P. (2009) Protein kinase D1 regulates matrix metalloproteinase expression and inhibits breast cancer cell invasion. Breast Cancer Res. 11, R13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Eiseler T., Döppler H., Yan I. K., Kitatani K., Mizuno K., Storz P. (2009) Protein kinase D1 regulates cofilin-mediated F-actin reorganization and cell motility through slingshot. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 545–556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Eiseler T., Hausser A., De Kimpe L., Van Lint J., Pfizenmaier K. (2010) Protein kinase D controls actin polymerization and cell motility through phosphorylation of cortactin. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 18672–18683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Eiseler T., Schmid M. A., Topbas F., Pfizenmaier K., Hausser A. (2007) PKD is recruited to sites of actin remodelling at the leading edge and negatively regulates cell migration. FEBS Lett. 581, 4279–4287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brändlin I., Hübner S., Eiseler T., Martinez-Moya M., Horschinek A., Hausser A., Link G., Rupp S., Storz P., Pfizenmaier K., Johannes F. J. (2002) Protein kinase C (PKC)η-mediated PKCμ activation modulates ERK and JNK signal pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 6490–6496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brändlin I., Eiseler T., Salowsky R., Johannes F. J. (2002) Protein kinase Cμ regulation of the JNK pathway is triggered via phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1 and protein kinase Cϵ. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 45451–45457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rozengurt E. (2011) Protein kinase D signaling: multiple biological functions in health and disease. Physiology 26, 23–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ernest Dodd M., Ristich V. L., Ray S., Lober R. M., Bollag W. B. (2005) Regulation of protein kinase D during differentiation and proliferation of primary mouse keratinocytes. J. Invest. Dermatol. 125, 294–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bollag W. B., Dodd M. E., Shapiro B. A. (2004) Protein kinase D and keratinocyte proliferation. Drug News Perspect. 17, 117–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhukova E., Sinnett-Smith J., Rozengurt E. (2001) Protein kinase D potentiates DNA synthesis and cell proliferation induced by bombesin, vasopressin, or phorbol esters in Swiss 3T3 cells. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 40298–40305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Azoitei N., Pusapati G. V., Kleger A., Möller P., Küfer R., Genze F., Wagner M., van Lint J., Carmeliet P., Adler G., Seufferlein T. (2010) Protein kinase D2 is a crucial regulator of tumour cell-endothelial cell communication in gastrointestinal tumours. Gut 59, 1316–1330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Guha S., Tanasanvimon S., Sinnett-Smith J., Rozengurt E. (2010) Role of protein kinase D signaling in pancreatic cancer. Biochem. Pharmacol. 80, 1946–1954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Seufferlein T. (2002) Novel protein kinases in pancreatic cell growth and cancer. Int. J. Gastrointest. Cancer 31, 15–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Obenauer J. C., Cantley L. C., Yaffe M. B. (2003) Scansite 2.0: proteome-wide prediction of cell signaling interactions using short sequence motifs. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3635–3641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Du C., Zhang C., Hassan S., Biswas M. H., Balaji K. C. (2010) Protein kinase D1 suppresses epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition through phosphorylation of snail. Cancer Res. 70, 7810–7819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Olmeda D., Moreno-Bueno G., Flores J. M., Fabra A., Portillo F., Cano A. (2007) SNAI1 is required for tumor growth and lymph node metastasis of human breast carcinoma MDA-MB-231 cells. Cancer Res. 67, 11721–11731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Peinado H., Olmeda D., Cano A. (2007) Snail, Zeb and bHLH factors in tumour progression: an alliance against the epithelial phenotype? Nat. Rev. Cancer 7, 415–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Peinado H., Del Carmen Iglesias-de la Cruz M., Olmeda D., Csiszar K., Fong K. S., Vega S., Nieto M. A., Cano A., Portillo F. (2005) A molecular role for lysyl oxidase-like 2 enzyme in snail regulation and tumor progression. EMBO J. 24, 3446–3458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Peinado H., Portillo F., Cano A. (2005) Switching on-off Snail: LOXL2 versus GSK3β. Cell Cycle 4, 1749–1752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhou B. P., Deng J., Xia W., Xu J., Li Y. M., Gunduz M., Hung M. C. (2004) Dual regulation of Snail by GSK-3β-mediated phosphorylation in control of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat. Cell Biol. 6, 931–940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Peinado H., Ballestar E., Esteller M., Cano A. (2004) Snail mediates E-cadherin repression by the recruitment of the Sin3A/histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1)/HDAC2 complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 306–319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hausser A., Link G., Bamberg L., Burzlaff A., Lutz S., Pfizenmaier K., Johannes F. J. (2002) Structural requirements for localization and activation of protein kinase C μ (PKCμ) at the Golgi compartment. J. Cell Biol. 156, 65–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hausser A., Link G., Hoene M., Russo C., Selchow O., Pfizenmaier K. (2006) Phospho-specific binding of 14-3-3 proteins to phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase III β protects from dephosphorylation and stabilizes lipid kinase activity. J. Cell Sci. 119, 3613–3621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hutti J. E., Jarrell E. T., Chang J. D., Abbott D. W., Storz P., Toker A., Cantley L. C., Turk B. E. (2004) A rapid method for determining protein kinase phosphorylation specificity. Nat. Methods 1, 27–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Döppler H., Storz P., Li J., Comb M. J., Toker A. (2005) A phosphorylation state-specific antibody recognizes Hsp27, a novel substrate of protein kinase D. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 15013–15019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. von Blume J., Knippschild U., Dequiedt F., Giamas G., Beck A., Auer A., Van Lint J., Adler G., Seufferlein T. (2007) Phosphorylation at Ser244 by CK1 determines nuclear localization and substrate targeting of PKD2. EMBO J. 26, 4619–4633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Peinado H., Moreno-Bueno G., Hardisson D., Pérez-Gómez E., Santos V., Mendiola M., de Diego J. I., Nistal M., Quintanilla M., Portillo F., Cano A. (2008) Lysyl oxidase-like 2 as a new poor prognosis marker of squamous cell carcinomas. Cancer Res. 68, 4541–4550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ouyang W., Li J., Zhang D., Jiang B. H., Huang D. C. (2007) PI-3K/Akt signal pathway plays a crucial role in arsenite-induced cell proliferation of human keratinocytes through induction of cyclin D1. J. Cell Biochem. 101, 969–978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wali R. K., Khare S., Tretiakova M., Cohen G., Nguyen L., Hart J., Wang J., Wen M., Ramaswamy A., Joseph L., Sitrin M., Brasitus T., Bissonnette M. (2002) Ursodeoxycholic acid and F6-D3 inhibit aberrant crypt proliferation in the rat azoxymethane model of colon cancer: roles of cyclin D1 and E-cadherin. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 11, 1653–1662 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zwijsen R. M., Klompmaker R., Wientjens E. B., Kristel P. M., van der Burg B., Michalides R. J. (1996) Cyclin D1 triggers autonomous growth of breast cancer cells by governing cell cycle exit. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 2554–2560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kimura M., Okano Y. (2005) Aurora kinases and cancer. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho 32, 1–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hirota T., Kunitoku N., Sasayama T., Marumoto T., Zhang D., Nitta M., Hatakeyama K., Saya H. (2003) Aurora-A and an interacting activator, the LIM protein Ajuba, are required for mitotic commitment in human cells. Cell 114, 585–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Prigent C., Giet R. (2003) Aurora A and mitotic commitment. Cell 114, 531–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Guha S., Rey O., Rozengurt E. (2002) Neurotensin induces protein kinase C-dependent protein kinase D activation and DNA synthesis in human pancreatic carcinoma cell line PANC-1. Cancer Res. 62, 1632–1640 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Harikumar K. B., Kunnumakkara A. B., Ochi N., Tong Z., Deorukhkar A., Sung B., Kelland L., Jamieson S., Sutherland R., Raynham T., Charles M., Bagherzadeh A., Foxton C., Boakes A., Farooq M., Maru D., Diagaradjane P., Matsuo Y., Sinnett-Smith J., Gelovani J., Krishnan S., Aggarwal B. B., Rozengurt E., Ireson C. R., Guha S. (2010) A novel small-molecule inhibitor of protein kinase D blocks pancreatic cancer growth in vitro and in vivo. Mol. Cancer Ther. 9, 1136–1146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jackson L. N., Li J., Chen L. A., Townsend C. M., Evers B. M. (2006) Overexpression of wild-type PKD2 leads to increased proliferation and invasion of BON endocrine cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 348, 945–949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ochi N., Tanasanvimon S., Matsuo Y., Tong Z., Sung B., Aggarwal B. B., Sinnett-Smith J., Rozengurt E., Guha S. (2011) Protein kinase D1 promotes anchorage-independent growth, invasion, and angiogenesis by human pancreatic cancer cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 226, 1074–1081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Dougherty M. K., Morrison D. K. (2004) Unlocking the code of 14-3-3. J. Cell Sci. 117, 1875–1884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Benzinger A., Muster N., Koch H. B., Yates J. R., 3rd, Hermeking H. (2005) Targeted proteomic analysis of 14-3-3σ, a p53 effector commonly silenced in cancer. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 4, 785–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.