Abstract

Statins are effective for reducing low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and cardiac events, but can produce muscle side effects. We have hypothesized that statin-related muscle complaints are exacerbated by exercise and influenced by factors including mitochondrial dysfunction, membrane disruption and/or calcium handling. The interaction between statins, exercise and muscle symptoms may be more effectively diagnosed and treated as rigorous scientific studies accumulate.

Keywords: cholesterol-lowering medication, muscle strength, aerobic capacity, myalgia, Vitamin D, HMG CoA Reductase Inhibitor

INTRODUCTION

Hydroxy-methyl-glutaryl (HMG) Coenzyme A (CoA) reductase inhibitors or statins are the most effective medications for managing elevated concentrations of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C). These drugs also offer one of the most effective strategies for reducing cardiovascular disease and have been documented to reduce cardiac events in both coronary artery disease (CAD) patients (21) and in previously healthy subjects (3). Statins are so effective that they are presently the most prescribed drugs in the United States and the world.

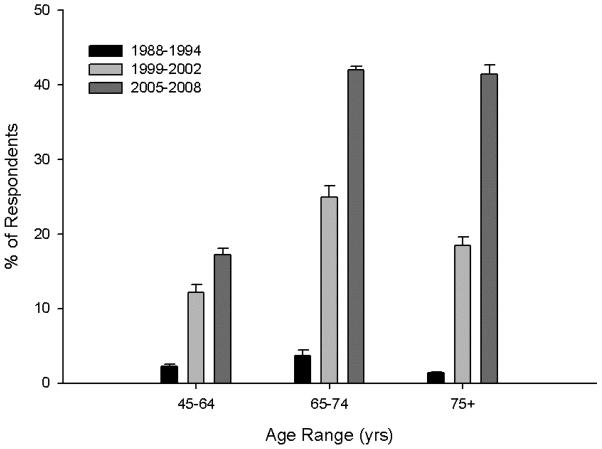

Treatment guidelines based primarily on serum LDL-C levels were established by the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Adult Treatment Panel III in May 2001. (5) These guidelines suggest an LDL-C treatment goal of <100 mg/dl for patients with established vascular disease, diabetes, or a calculated 10-year CAD risk of >20 %. Several recent clinical trials support even lower LDL-C goals for many patients. The Heart Protection Study (HPS) observed a 23% reduction in CAD events among 20,536 high risk patients treated with simvastatin 40 mg daily for 5 years (17). A similar percent reduction in cardiac events was seen in the 6,793 patients whose baseline LDL-C was <116 mg/dl. Moreover, an NCEP update stated that an LDL-C goal of <70 mg/dl is “a reasonable clinical strategy” for patients at very high risk of CAD, and that older persons also benefit from LDL-C reduction. Recently published results from the Justification for the Use of Statins in Prevention: an Intervention Trial Evaluating Rosuvastatin (JUPITER) trial, indicate that healthy individuals without hyperlipidemia but with elevated high-sensitivity C-reactive protein levels benefit from a reduction in the incidence of major cardiovascular events following several years treatment with 20 mg rosuvastatin (22). These collective results suggest that increasing numbers of patients, including the elderly and those with low initial LDL-C levels, will be treated with larger doses of the more potent statins. Indeed, the Centers for Disease Control reported that from 2005–2008 approximately 25% of U.S. adults > 45 yrs of age reported using a prescription statin drug in the last 30 days, a roughly 10-fold increase over 1988–1994 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Trends in statin drug use among adults in the United States are shown by age group (45–64, 65–74, and 75+ years of age) over three age ranges (1989–1994, 1999–2002, and 2005–2008). Data are self-report data (group means ± S.E.M.) from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey with statin use defined as taking a prescription statin over the past 30 day period. Data obtained from www.cdc.gov/nchs.

MUSCLE SIDE EFFECTS ASSOCIATED WITH STATIN TREATMENT

Statins are extremely well tolerated by the majority of patients, but can produce a variety of muscle-related complaints in some individuals. The most serious risk of these drugs is rhabdomyolysis with acute renal failure and even death. This risk was emphasized by the withdrawal of cerivastatin in August 2001 after the drug was associated with approximately 100 rhabdomyolysis related deaths. Fortunately, clinically important rhabdomyolysis with statins is rare with an overall reported incidence of fatal rhabdomyolysis of 1.5 deaths per 106 prescriptions (27). Unfortunately, statins are much more frequently associated with “mild muscle complaints” including myalgia, cramps and weakness. Myalgia can occur with or without creatine kinase (CK) elevations, a serum marker of muscle damage. The reported incidence of myalgia during therapy with the more powerful statins has varied from 1% in pharmaceutical company reports (20) to 25% (19) of patients. It is impossible to discern the true incidence of mild muscle complaints because these problems typically are not examined in pharmaceutical sponsored trials and because of study design. In HPS, for example, subjects were not randomized to simvastatin or placebo until they had successfully tolerated simvastatin 40 mg for a 5 week introductory period (17), and most trials report muscle symptoms only when CK values exceeded 10 times upper limits of normal.

Recent clinical reports, however, have confirmed clinicians’ suspicions that statins frequently produce muscle symptoms. Among 7924 patients treated with high dose statins, 11% developed muscle symptoms, 4% had symptoms severe enough to interfere with daily activities, and 0.4% were actually confined to bed with their symptoms (2). We and others have suggested various approaches to managing statin myalgia, but this management often requires withdrawal of these life-saving medications.

EFFECTS OF STATINS ON MUSCLE STRENGTH AND AEROBIC PERFORMANCE

Muscle weakness is also a clinically acknowledged complication of statin use in some individuals. Data from direct assessments of muscle weakness (i.e., strength testing) and statins are limited and have produced inconsistent conclusions. We recently published a review summarizing the 6 published articles documenting the effect of statins on skeletal muscle strength in humans (12). To our knowledge, Phillips et al were the first to examine the association of statins and muscle strength in 4 subjects (2 women aged 76 and 66 years; 2 men aged 66 and 62 years) with symptoms of statin myopathy despite normal CK levels. These authors noted reductions of 10–40% in hip abduction strength. Similarly, another study documented statin-induced myopathic proximal weakness in patients with neurological disease. Scott et al employed a prospective cohort design to examine the effect of statin therapy on muscle function, muscle mass and fall risk in 774 individuals, aged 50–79 years, participating in the Tasmanian Older Adults Cohort Study. Statin users at 2.6 years follow up had significantly lower mean leg strength than statin non-users at follow up, and muscle strength and quality decreased significantly in those who reported statin use at baseline and follow up when compared to all other patients. Interestingly, both muscle strength and quality were significantly decreased in statin users at baseline and follow up compared to those who stopped statin therapy, although the latter group was small (n=11). Such results suggest that statins decrease muscle strength in older individuals and that this decrease is reversible with treatment cessation. Conversely, a larger cross-sectional study of statin users vs. nonusers found slightly improved performance on a sit-to-stand chair test (a measure of proximal muscle strength) with statin use in older community-dwelling adults, suggesting that low dose statin therapy improved strength in an asymptomatic cohort. Still other studies have shown no effects of high-dose statin therapy on handgrip, upper body, and leg muscle strength.

There are also sparse data on the effects of statins on aerobic exercise performance; again these findings were covered in our recent review on the topic (12). One study provided atorvastatin 5–10 mg to 5 healthy middle aged men (54±10 yrs) and one woman. Exercise results in these subjects were compared with results from 9 men and 2 women who developed muscle complaints plus CK elevations during statin alone (n=6), statin and fibrate (n=3) or statin and niacin (n=2) therapy. There was no effect of statin therapy on maximal oxygen uptake (VO2 max), a measure of aerobic fitness, in the normal patients, but VO2 max was significantly lower in the myopathic patients, a finding the authors attributed to these patients’ physical inactivity due to their myopathy. Interestingly, the resting respiratory exchange ratio (RER = VCO2/VO2) increased with statin therapy in the normal subjects (0.75±0.02 to 0.86±0.06), and was also elevated in the myopathic patients off statin therapy (0.90±0.07). RER decreases with fat oxidation and increases as carbohydrate is used as fuel, but is a crude measure of these processes. The authors interpreted their findings as showing that statins impair fat metabolism in healthy patients and that victims of statin myopathy have a pretreatment abnormality in fat metabolism that is exacerbated by statin therapy leading to the muscle complaints. There was no apparent change in the onset of lactate accumulation or “anaerobic threshold” during the exercise test, however, which argues against an alteration in exercise fat metabolism with statin treatment. One additional study of 195 non-insulin diabetics noted a 6% increase in resting RER (0.78 to 0.83), which the authors attributed to improved glucose metabolism with statin treatment, but exercise parameters were not measured in that study.

By contrast several studies have found no evidence of an effect of statins on aerobic exercise performance. For example, VO2 max and RER did not change in 10 patients after 12 weeks of simvastatin therapy (80mg/day), suggesting that short term high dose statin therapy does not impair aerobic capacity or alter substrate metabolism in older asymptomatic patients. In addition, Coen et al. observed that VO2 max increased by 29% ± 6% in a group of hypercholesteremic and physically inactive subjects simultaneously treated with 10 mg/day rosuvastatin and undergoing 10 weeks of exercise training. These results suggest that statins do not eliminate the aerobic training response, but this study did not include an untreated, exercise-trained control group so data must be interpreted with caution. Moreover, in clinical populations such as adults with heart failure and claudication, statin therapy improves average walking distance and/or pain free walking time. Cumulatively, therefore, these equivocal results suggest that, despite their documented myopathic effects, the effects of statins on muscle strength and aerobic exercise performance are unclear.

STATIN RELATED-COMPLAINTS ARE EXACERBATED BY EXERCISE

We have hypothesized that statin-related muscle complaints may be exacerbated by exercise, based on several reports indicating that athletes and/or physically active individuals are less likely to tolerate statin therapy. This was based on our observation in 1990 of 36 participants in a clinical trial comparing the lipid effects of fluvastatin vs lovastatin. Four individuals developed creatine kinase (CK) elevations, an index of muscle injury, and each elevation was associated with recent physical exertion. One subject, who had not habitually exercised, performed a weight lifting workout and presented with severe muscle pain and a CK level 100 times the upper limit of normal (29). Furthermore, Sinzinger and O’Grady monitored statin use and muscle side effects in 22 professional athletes with familial hypercholesterolemia. Only 20% of these top athletes ultimately tolerate statin therapy despite multiple trials with multiple medications (26). Similarly, Bruckert et al. observed more muscle symptoms in physically active individuals than sedentary individuals. The incidence of muscle pain with statin therapy increased with the level of physical activity from 10.8% in those engaging in leisure-type physical activity to 14.7% in those regularly engaging in vigorous activity, suggesting that statin-associated muscle side effects are provoked by physical activity. The muscle pain prevented even moderate exertion during everyday activities in 38% of the patients with myalgia on statins (2).

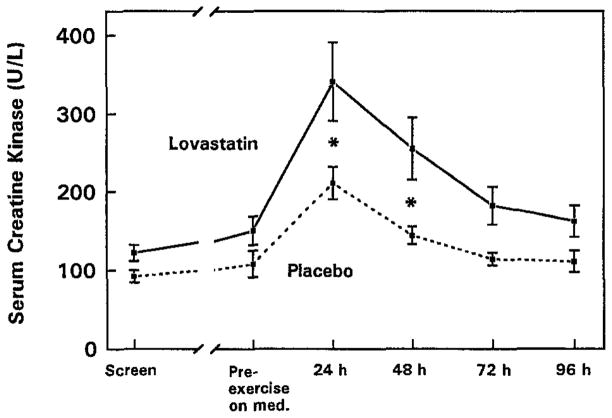

We then tested this hypothesis directly in a double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 59 healthy men aged 18 to 65 years with low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels greater than 130 mg/dL (31).Subjects were randomly assigned to lovastatin (40 mg/d) or placebo for 5 weeks. Subjects completed 45 minutes of downhill treadmill walking (−15% grade) at 65% of their predetermined maximum heart rate after 4 weeks of treatment. CK levels were measured before exercise and daily for 4 days after the treadmill exercise. CK levels were 62% and 77% higher in the lovastatin group 24 and 48 hours after treadmill exercise after adjusting for initial CK differences between groups at baseline (Figure 2). While CK levels may not fully correlate to the degree of muscle injury, these data support that HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors exacerbate exercise-induced skeletal muscle injury.

Figure 2.

Serum CK levels (U/L) in men treated with 40 mg/day lovastatin (n=22) or placebo (n=27) before treatment (screen), after 4 weeks of lovastatin or placebo (pre-exercise on med.), and daily for 4 days after downhill walking. *P < .05. (Reprinted from (31). Copyright © 1997 Elsevier. Used by permission.)

A subsequent study examined the CK response to downhill walking in subjects treated with low and high dose of atorvastatin to determine whether statin-induced elevations in muscle damage are dose dependent (11). Seventy nine healthy men with LDL cholesterol>100mg/dL were discontinued from statin medications for 6 weeks and randomly assigned to atorvastatin 10mg (N=42) or 80 mg (N=37) for 5 weeks. Similar to the previous study, subjects completed 45 minutes of downhill treadmill walking (−15% grade) at 65% of their predetermined maximum heart rate in the fifth week of treatment. Leg muscle soreness and plasma CK were measured daily for 4 days following the exercise. CK and muscle soreness increased above pre-exercise levels in all subjects after the exercise, with no differences in the CK response between the high and low dose treatment groups at any time point. We thereby concluded that that exercise can increase CK levels with even low dose statin therapy. It is possible, however, that downhill walking may not be sufficiently sensitive to detect dose-dependent differences in the effects of statin therapy on eccentric exercise-induced muscle damage.

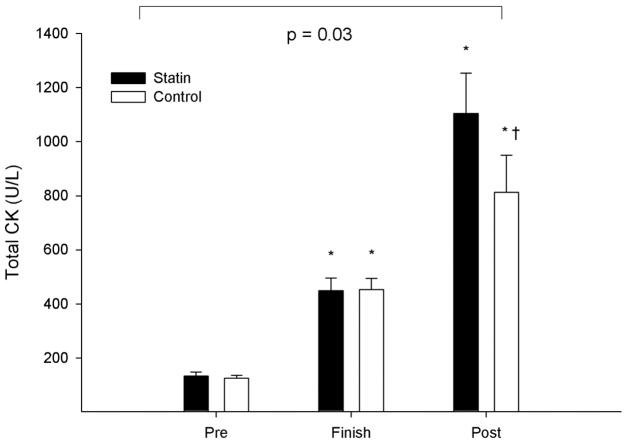

We have confirmed that eccentric exercise during statin therapy does increase CK levels more than exercise on placebo in our most recent study, conducted at the 2011 Boston Marathon (18). The Boston race course drops approximately 440 feet, despite the notorious Newton hills, so includes a lot of eccentric exercise. We measured total creatine kinase (CK) in thirty seven statin-using athletes (29 men and 8 women) and 43 controls (30 men and 13 women) running the race. Subjects were on a variety of statin medications and doses. Venous blood samples were obtained the day before as well as within 1-hour and 24-hours after the race. The exercise-related increase in CK 24 hours after exercise, adjusted for changes in plasma volume, was greater in statin users than controls (Figure 3). Notably, there was no relationship between statin potency and the changes in CK immediately and 24 hours after exercise, although increases in CK at both finish and 24 hours after the race measurements were directly related to age in the statin users. We concluded that statins increase exercise-related muscle injury, and the susceptibility to exercise-induced muscle injury with statins does not appear to be dose-dependent but does increase with age. Age increases serum and ultimately muscle concentrations of statins, and is considered a risk factor for skeletal muscle myopathy. Therefore, it is plausible that age magnifies the effect of statins on exercise-associated elevations in CK due to the same mechanism by which age increases the risk of myopathy.

Figure 3.

Group means (± SD) of total CK before (Pre), immediately after (Finish), and 24 hours after the 2011 Boston Marathon (Post) in 37 individuals treated with statins and in 43 non-statin treated controls, including the p-value for the group-by-time interaction. * denotes a significant effect change relative to the baseline (pre) value at p < 0.05 within each group and † denotes a significant difference between groups at p < 0.05. (Reprinted from (18). Copyright © 1997 Elsevier. Used by permission.)

It should be noted that other studies have failed to confirm greater increases in CK levels following eccentric (18;28) exercise during statin treatment, possibly due to small sample sizes and the use of a cross-over design and/or repeated bouts of exercise. It is known, for example, that a single exercise session protects the muscle from subsequent injury over the next several months, so that cross-over designs and/or those with multiple bouts of exercise may obscure any effect of statin treatment (4). In support of this hypothesis, Meador and Huey recently published a study showing that 2 weeks of prior run training prevented cerivastatin-associated force loss and increased fatigability in mice (16).

MECHANISMS OF EXERCISE-ASSOCIATED DAMAGE

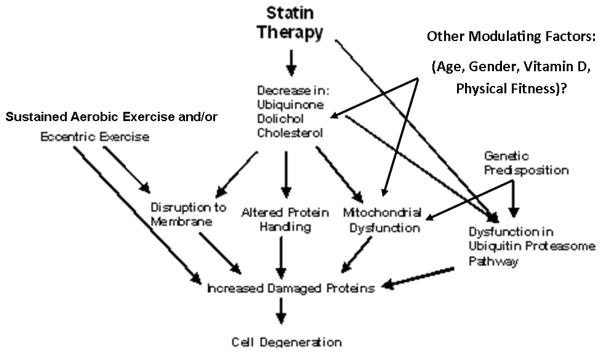

Sustained muscular contraction during periods of glycogen depletion and reduced adenosine-5′-triphosphate (ATP) availability result in membrane permeability and fiber damage, permitting muscle enzyme efflux that is proportional to the duration and intensity of the exercise. There are several mechanisms by which statins could amplify this process (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

A schematic of the potential mechanisms by which statin therapy and exercise result in skeletal muscle damage.

The most popular but largely untested theory for statin myopathy at rest and during exercise is depletion of intramuscular CoQ10 producing mitochondrial dysfunction, subsequent abnormal muscle energy metabolism and ultimately symptoms. We have recently summarized the data linking CoQ10 to statin myopathy (15). Serum CoQ10 levels decrease during statin therapy, but CoQ10 is transported in lower density lipoprotein particles and its decrease is commensurate with decreases in blood cholesterol. This suggests that the decrease in serum CoQ10 is due to a reduction in transport particles. CoQ10 levels do not decrease during ezetimbie and cholestyramine therapy, however, despite reductions in LDL levels so it is possible that the effect of statins on CoQ10 is independent of their reductions in transport particles. Muscle biopsies studies have failed to detect consistent reductions in muscle CoQ10 levels although one study in statin naive subjects found microscopic evidence of statin myopathy and reductions of 30% in intramuscular CoQ10 levels in subjects treated with simvastatin 80 mg for 8 weeks. Another report noted muscle CoQ10 levels 2–4 standard deviations below normal in 50% of patients with statin myopathy.

Similarly there is emerging animal and human evidence for a disruption in mitochondrial function with statin therapy. Bouitbir et al. recently characterized mitochondrial function and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in skeletal muscle after exhaustive exercise in atorvastatin-treated rats relative to untreated rats (1). At rest, ROS level was increased by 60% in the plantaris muscle of atorvastatin vs. control rats; the difference was even more pronounced (226% increase with atorvastatin) following exhaustive exercise. Moreover, atorvastatin treatment reduced the distance covered during exhaustive exercise and this correlated to a 39% decrease in maximal mitchondiral respiration observed relative to the control group. Similarly, phosphocreatine (PCr) exercise recovery time following calf flexion exercise increased after a 4-weeks of statin therapy in 10 hypercholesteremic patients, suggesting again that statins impair mitochondrial oxidative function (34). The hypothesis that statins deleteriously affect mitochondrial function is supported by our observation that transcriptional patterns between statin myopathic and statin-tolerant subjects differ after eccentric leg exercise; symptomatic subjects treated with a statin exhibited decreased skeletal muscle gene expression for oxidative phosphorylation-related and mitochondrial ribosomal protein genes relative to asymptomatic subjects (9). Interestingly, mitochondrial gene expression was also different at baseline before statin treatment between subjects who had and had not previously tolerated statin therapy.

To our knowledge only two small studies that have administered CoQ10 to patients with statin myalgia, but neither tested muscle injury following exercise and these reports produced contrasting results. Caso et.al. randomly assigned patients with prior statin myalgia and currently on statin treatment to low dose CoQ10 (100 mg/day, n = 18) or vitamin E (400 IU/day, n = 14) for 30 days. Pain severity decreased by 40% and pain interference with daily activities decreased by 38% in the group treated with CoQ10, but neither pain severity nor pain interference with daily activities changed with vitamin E. Young et.al. randomized 44 patients with statin myalgia to CoQ10 200 mg/day or placebo during upward dose titration of simvastatin from 10 to 40 mg/day, but found no difference in myalgia score, adherence to simvastatin treatment or the number of patient tolerating the highest simvastatin dose.

Alternatively, statins may modify the response of muscle to exercise stress by altering skeletal muscle membrane integrity as well as the actions of the ubiquitin proteasome pathway (UPP), protein folding, and catabolism, thereby disrupting the balance between cell degradation and repair. For example, the skeletal muscle membrane content is predominantly composed of phospholipids, which, if reduced by statin therapy, may exacerbate damage associated with bouts of exercise. Moreover, the UPP system is responsible for the recognition and degradation of many skeletal muscle proteins and is involved in conditions involving muscle mass loss such as cancer cachexia, diabetes, uremia, and sepsis. Atrogin-1, a component of the UPP system, is induced early in the atrophy process. We demonstrated marked reductions in Atrogin transcription in a human, exercise-injury model of statin myopathy (32). In contrast, Hanai and colleagues found increases in atrogin-1 expression in human skeletal muscle in patients with statin myopathy, and animal cells lacking atrogin-1 were resistant to statin myotoxicity (8). Consequently, the role of the UPP system in statin-induced myotoxicity is not defined. Furthermore, the factors activating this system are not clear and could involve changes in energy production. Statin therapy may also upregulate skeletal muscle apoptosis via activation of calpain (which stimulates programmed cell death), as has been observed in human muscle cells following treatment with simvastatin. Moreover, statin treatment results in repression of the anti-apoptosis gene (Birc4) and activation of the pro-apoptosis gene in human muscle cells (Cflar) (35).

Finally, statin therapy could alter calcium handling such that calcium leaking from the mitochondria might impair sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium cycling. For example, 2 months treatment of rats with fluvastatin and atorvastatin caused an alteration of calcium homeostasis, increasing resting cytosolic calcium up to 60% with the higher fluvastatin dose (13). Since animal research suggests that type II glycolytic muscle fibers are most vulnerable to statin associated muscle injury following cervistatin treatment and treadmill exercise in female rats, carbohydrate depletion during exercise could make these fibers particularly susceptible to injury in humans as well. Differences in fiber type composition between individuals may also consequently impact muscle response to the combination of statin and exercise.

POTENTIAL MODIFIERS OF THE INTERACTION BETWEEN STATINS, SKELETAL MUSCLE, AND EXERCISE

We have recently reviewed the growing body of evidence suggesting that genetic factors increase an individual’s susceptibility to statin myopathy (6). For example, a genome-wide scan conducted in 85 subjects with statin-induced myopathy yielded asingle strong association of myopathy with the rs4363657 single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) located within SLCO1B1. SLCO1B1 encodes the organic anion-transporting polypeptide (OATP) 1B1, thereby regulating the hepatic uptake of statins. Vladutiu and colleagues tested 110 patients with primarily statin-induced myopathies and noted that 10% of these patients had at least one abnormal allele for a gene affecting muscle metabolism. A more recent study of 190 patients with severe statin myopathy resulted in the identification of three single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the eyes shut homolog (EYS) on chromosome 6, which may play a role maintaining the structural integrity of skeletal muscle (10). We have also shown genetic variants predictive of muscular side effects in patients treated with statins. In a recent multi-site study of 377 patients with statin-associated myalgia and 416 patients tolerant of statins, three candidate genes (COQ2, ATP2B1, and DMPK), representing pathways involved in Co Q10 synthesis, calcium homeostasis, and myotonic dystonia, respectively, were validated as markers for myalgia (25). A previous study found a relationship between statin myalgia and two polymorphisms in serotonergic genes such that single nucleotide polymorphisms in the HTR3B and HTR7 genes, rs2276307 and rs1935349, were significantly associated with the myalgia score of probable or definitive myalgia (23).

Similarly, there appears to be a genetic predisposition to non-exercise induced CK increases during statin treatment, as individuals homozygous for the cytochrome P-450 (CYP) 3A genetic variant (CYP3A5*3) demonstrated greater serum CK levels than patients heterozygous for CYP3A5*3 following atorvastatin treatment (33). We also screened for genetic associations with CK levels in 102 patients receiving statin therapy, finding that single nucleotide polymorphisms in the angiotensin II Type 1 receptor and nitric oxide synthase 3 genes were significantly associated with CK activity (24).

Since non-statin treated individuals also show genetic susceptibility to exercise-induced muscle damage, we have hypothesized that the interaction between muscle side effects and damage, statin therapy, and exercise is likely to be influenced by expression of certain genetic variants. However, to the best of our knowledge, no data yet exist to directly confirm this hypothesis.

We also recently reviewed the relationship between Vitamin D deficiency (commonly measured as 25 hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] levels below 30 ng/mL) and statin myopathy (7). Cholesterol is used to synthesize 7-dehydrocholesterol (7-DHC), the precursor to Vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol), endogenously. Interestingly, while it is expected that statin therapy would reduce both cholesterol and serum Vitamin D, studies to date have shown that statin therapy either has no effect on Vitamin D, or, conversely, increases Vitamin D levels in asymptomatic adults. Despite these latter findings, case reports, clinical anecdotes and cross-sectional studies have linked Vitamin D insufficiency to statin myopathy. For example, among 11 patients with statin myalgia prompting statin discontinuation, 8 were vitamin D insufficient (25(OH) D < 24 ng/mL) and 3 of these were severely deficient (25(OH) D < 12 ng/mL). Six of the 8 patients had complete resolution and 2 had significant improvement of myalgia over approximately 3 months with cessation of the statin and vitamin D replacement (1000–10,000 units/day); moreover, 4 of the 6 patients agreed to re-challenge with the same statin after vitamin D repletion and tolerated statin therapy for at least 6 months without myalgia. Another study of statin-treated patients noted that serum vitamin D levels at enrollment were lower in 128 patients with myalgia vs. 493 asymptomatic patients. Of the 82 vitamin D deficient, myalgic patients (vitamin D levels 20.8 ± 7.1 ng/mL), 38 were given vitamin D (ergocalciferol 50,000 units/week for 12 weeks), with an increase in serum vitamin D from 20.4 ± 7.3 to 48.2 ± 17.9 ng/mL and resolution of myalgia in 35 (92%).

Molecular mechanisms of vitamin D action on muscle tissue include genomic and non-genomic effects via receptors present in and on muscle cells and Vitamin D deficiency alone can cause skeletal muscle myopathy as well as decreased muscle strength.. There is presently no definitive evidence that vitamin D contributes to statin myalgia, but this possibility does warrant further scientific inquiry (7).

SUMMARY

Statin therapy, while well-tolerated by the majority of patients, can be associated with muscle-related side effects and may exacerbate CK release and presumably the skeletal muscle damage associated with eccentric exercise. However, gaps in physiological, molecular, mechanistic and clinical knowledge regarding muscle effects of statin therapy remain substantial, with many unresolved issues and equivocal findings. Key questions include:

Are statin-induced muscle side effects a continuum from myalgia to rhabdomyositis, and caused by similar mechanisms? This is an important question for clinicians who must decide whether or not continuing statin therapy in myalgic subjects increases the risk of life-threatening rhabdomyolysis.

Should clinicians discontinue statin use for several days prior to endurance events, especially if heat stress or other potential exacerbators of rhabdomyolysis may occur? The latter could be particularly important for older runners who appear more likely from our 2011 Boston Marathon to experience muscle injury.

Can we develop better, more consistent, screening and testing techniques to assess individuals who may be at risk for myalgia, decreases in muscle strength and aerobic performance, and increased muscle damage with statin treatment? This could include genetic profiles designed to identify genes associate with statin muscle complaints.

Are statin-associated muscle complaints altered by acute and chronic physical activity, and what other factors contribute to the relationship between statins and skeletal muscle function? Discrepant results regarding the effects of statins on muscle strength, aerobic performance, and CK levels following exercise suggest that multiple additional factors influence the effects of statins on skeletal muscle at rest and during exercise. To date, although evidence supports the hypothesis that acute and chronic resistance and aerobic exercise may exacerbate statin-associated muscle complaints in some individuals, there are a paucity of carefully controlled, adequately powered, rigorously designed studies to fully document this.

Finally, can increases in creatine kinase associated with exercise and statin therapy be confirmed with more direct measurements of muscle damage in human subjects that also provide important information about underlying mechanisms such as apoptosis, calcium handling, and oxidative stress? The majority of human studies on this topic have assessed noninvasive markers of muscle damage or assessed molecular and genetic pathways in resting skeletal muscle treated with statin therapy. There are also limited animal studies investigating statin-induced skeletal muscle damage with exercise.

A recent editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine emphasized the need for clinical trials in statin-intolerant patients (14). There is a similar need for large-scale trials investigating the effects of statins on skeletal muscle strength, aerobic performance, and exercise-induced muscle damage over a long-term duration of treatment, in individuals with and without statin myalgia. To this end, we have recently completed data collection of an NHBLI-funded (The Effect of STatins On Skeletal Muscle Function and Performance, or STOMP) study assessing creatine kinase, exercise capacity, and muscle strength before and after atorvastatin 80 mg or placebo treatment for 6 months in 420 healthy, statin-naive subjects (30). We believe that these emerging results will address several of the inconsistencies in the literature to date regarding impacts of statin therapy on muscle and aerobic outcomes. Nonetheless, with an aging population, ever-lowering LDL cholesterol guidelines, and increasing numbers of statin prescriptions, research aimed at better elucidating the relationship between exercise, statin therapy and skeletal muscle will be critical for refining treatment guidelines.

SUMMARY.

This review details the effects of statins on skeletal muscle, particularly following exercise, and explores possible mechanisms underlying statin-associated muscle damage.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the assistance of Amanda Augeri, Jeffrey Capizzi, Lindsay Lorson, and William Roman in assisting with work cited in this manuscript. Due to reference limitations, we could not cite the individual work covered in our previously-published review papers (6;7;12;15). We acknowledge the work of all authors whose work was covered in those papers.

Funding for this work was received from NHLBI 5R01HL081893 (Thompson) and NHLBI R01HL098085 (Parker)

Footnotes

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: Beth A. Parker has no disclosures. Paul D. Thompson reports receiving research grants from the National Institutes of Health, GlaxoSmithKline, Anthera, B. Braun, Genomas, Roche, Aventis, Novartis, and Furiex; serving as a consultant for Astra Zenica, Furiex, Regeneron, Merck, Takeda, Roche, Genomas, Abbott, Lupin, Runners World, Genzyme, Sanolfi, Pfizer, and GlaxoSmithKline; receiving speaker honoraria from Merck, Pfizer, Abbott, Astra Zenica, GlaxoSmithKline, and Kowa: owing stock in Zoll, General Electric, JA Wiley Publishing, Zimmer, J&J, Sanolfi-Aventis and Abbott; and serving as a medical legal consultant on cardiac complications of exercise, statin myopathy, tobacco, ezetimibe and non-steroidals.

References

- 1.Bouitbir J, Charles AL, Rasseneur L, Dufour S, Piquard F, Geny B, Zoll J. Atorvastatin treatment reduces exercise capacities in rats: involvement of mitochondrial impairments and oxidative stress. J Appl Physiol. 2011;111(5):1477–83. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00107.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bruckert E, Hayem G, Dejager S, Yau C, Begaud B. Mild to moderate muscular symptoms with high-dosage statin therapy in hyperlipidemic patients--the PRIMO study. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2005;19(6):403–14. doi: 10.1007/s10557-005-5686-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Downs JR, Clearfield M, Weis S, Whitney E, Shapiro DR, Beere PA, Langendorfer A, Stein EA, Kruyer W, Gotto AM., Jr Primary prevention of acute coronary events with lovastatin in men and women with average cholesterol levels: results of AFCAPS/TexCAPS. Air Force/Texas Coronary Atherosclerosis Prevention Study. JAMA. 1998;279(20):1615–22. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.20.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evans WJ, Meredith CN, Cannon JG, Dinarello CA, Frontera WR, Hughes VA, Jones BH, Knuttgen HG. Metabolic changes following eccentric exercise in trained and untrained men. J Appl Physiol. 1986;61(5):1864–8. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1986.61.5.1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285:2486–2497. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghatak A, Faheem O, Thompson PD. The genetics of statin-induced myopathy. Atherosclerosis. 2010;210(2):337–43. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gupta A, Thompson PD. The relationship of vitamin D deficiency to statin myopathy. Atherosclerosis. 2011;215(1):23–9. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanai J, Cao P, Tanksale P, Imamura S, Koshimizu E, Zhao J, Kishi S, Yamashita M, Phillips PS, Sukhatme VP, et al. The muscle-specific ubiquitin ligase atrogin-1/MAFbx mediates statin-induced muscle toxicity. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(12):3940–51. doi: 10.1172/JCI32741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hubal MJ, Reich KA, De BA, Bilbie C, Clarkson PM, Hoffman EP, Thompson PD. Transcriptional deficits in oxidative phosphorylation with statin myopathy. Muscle Nerve. 2011;44(3):393–401. doi: 10.1002/mus.22081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Isackson PJ, Ochs-Balcom HM, Ma C, Harley JB, Peltier W, Tarnopolsky M, Sripathi N, Wortmann RL, Simmons Z, Wilson JD, et al. Association of common variants in the human eyes shut ortholog (EYS) with statin-induced myopathy: evidence for additional functions of EYS. Muscle Nerve. 2011;44(4):531–8. doi: 10.1002/mus.22115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kearns AK, Bilbie CL, Clarkson PM, White CM, Sewright KA, O’Fallon KS, Gadarla M, Thompson PD. The creatine kinase response to eccentric exercise with atorvastatin 10 mg or 80 mg. Atherosclerosis. 2008;200(1):121–5. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krishnan GM, Thompson PD. The effects of statins on skeletal muscle strength and exercise performance. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2010;21(4):324–8. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e32833c1edf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liantonio A, Giannuzzi V, Cippone V, Camerino GM, Pierno S, Camerino DC. Fluvastatin and atorvastatin affect calcium homeostasis of rat skeletal muscle fibers in vivo and in vitro by impairing the sarcoplasmic reticulum/mitochondria Ca2+-release system. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;321(2):626–34. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.118331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maningat P, Breslow JL. Needed: pragmatic clinical trials for statin-intolerant patients. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(24):2250–1. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1112023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marcoff L, Thompson PD. The role of coenzyme Q10 in statin-associated myopathy: a systematic review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49(23):2231–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meador BM, Huey KA. Statin-associated changes in skeletal muscle function and stress response after novel or accustomed exercise. Muscle Nerve. 2011;44(6):882–9. doi: 10.1002/mus.22236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin in 20, 536 high-risk individuals: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360(9326):7–22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09327-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parker BA, Augeri AL, Capizzi JA, Ballard KD, Troyanos C, Baggish AL, D’Hemecourt PA, Thompson PD. Effect of statins on creatine kinase levels before and after a marathon run. Am J Cardiol. 2012;109(2):282–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phillips PS, Haas RH, Bannykh S, Hathaway S, Gray NL, Kimura BJ, Vladutiu GD, England JD. Statin-associated myopathy with normal creatine kinase levels. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(7):581–5. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-7-200210010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Physicians’ Desk Reference. Montvale, NJ: Medical Economics; 2002. p. 56. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S) Lancet. 1994;344(8934):1383–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ridker PM, Danielson E, Fonseca FA, Genest J, Gotto AM, Jr, Kastelein JJ, Koenig W, Libby P, Lorenzatti AJ, Macfadyen JG, et al. Rosuvastatin to prevent vascular events in men and women with elevated C-reactive protein. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(21):2195–207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruano G, Thompson PD, Windemuth A, Seip RL, Dande A, Sorokin A, Kocherla M, Smith A, Holford TR, Wu AH. Physiogenomic association of statin-related myalgia to serotonin receptors. Muscle Nerve. 2007;36(3):329–35. doi: 10.1002/mus.20871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruano G, Thompson PD, Windemuth A, Smith A, Kocherla M, Holford TR, Seip R, Wu AH. Physiogenomic analysis links serum creatine kinase activities during statin therapy to vascular smooth muscle homeostasis. Pharmacogenomics. 2005;6(8):865–72. doi: 10.2217/14622416.6.8.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruano G, Windemuth A, Wu AH, Kane JP, Malloy MJ, Pullinger CR, Kocherla M, Bogaard K, Gordon BR, Holford TR, et al. Mechanisms of statin-induced myalgia assessed by physiogenomic associations. Atherosclerosis. 2011;218(2):451–6. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sinzinger H, O’Grady J. Professional athletes suffering from familial hypercholesterolaemia rarely tolerate statin treatment because of muscular problems. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;57(4):525–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2004.02044.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Staffa JA, Chang J, Green L. Cerivastatin and reports of fatal rhabdomyolysis. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(7):539–40. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200202143460721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thompson PD, Gadaleta PA, Yurgalevitch S, Cullinane E, Herbert PN. Effects of exercise and lovastatin on serum creatine kinase activity. Metabolism. 1991;40(12):1333–6. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(91)90039-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thompson PD, Nugent AM, Herbert PN. Increases in creatine kinase after exercise in patients treated with HMG Co-A reductase inhibitors. JAMA. 1990;264(23):2992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thompson PD, Parker BA, Clarkson PM, Pescatello LS, White CM, Grimaldi AS, Levine BD, Haller RG, Hoffman EP. A randomized clinical trial to assess the effect of statins on skeletal muscle function and performance: rationale and study design. Prev Cardiol. 2010;13(3):104–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7141.2009.00063.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thompson PD, Zmuda JM, Domalik LJ, Zimet RJ, Staggers J, Guyton JR. Lovastatin increases exercise-induced skeletal muscle injury. Metabolism. 1997;46(10):1206–10. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(97)90218-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Urso ML, Clarkson PM, Hittel D, Hoffman EP, Thompson PD. Changes in ubiquitin proteasome pathway gene expression in skeletal muscle with exercise and statins. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25(12):2560–6. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000190608.28704.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilke RA, Moore JH, Burmester JK. Relative impact of CYP3A genotype and concomitant medication on the severity of atorvastatin-induced muscle damage. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2005;15(6):415–21. doi: 10.1097/01213011-200506000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu JS, Buettner C, Smithline H, Ngo LH, Greenman RL. Evaluation of skeletal muscle during calf exercise by 31-phosphorus magnetic resonance spectroscopy in patients on statin medications. Muscle Nerve. 2011;43(1):76–81. doi: 10.1002/mus.21847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu JG, Sewright K, Hubal MJ, Liu JX, Schwartz LM, Hoffman EP, Clarkson PM. Investigation of gene expression in C(2)C(12) myotubes following simvastatin application and mechanical strain. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2009;16(1):21–9. doi: 10.5551/jat.e551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]