Abstract

The sustainability of an occupational sun safety program, Go Sun Smart (GSS), was explored in a randomized trial, testing dissemination strategies at 68 U.S. and Canadian ski areas in 2004-2007. All ski areas received GSS from the National Ski Areas Association through a Basic Dissemination Strategy (BDS) using conference presentations and free materials. Half of the ski areas were randomly assigned to a theory-based Enhanced Dissemination Strategy (EDS) with personal contact supporting GSS use. Use of GSS was assessed at immediate and long-term follow-up posttests by on-site observation. Use of GSS declined from the immediate (M=5.72) to the long-term follow-up (M=6.24), F[1,62]=6.95, p=.01, but EDS ski areas (M=6.53) continued to use GSS more than BDS ski areas (M=4.49), F(1,62)=5.75, p=0.02, regardless of observation, F(1,60)=0.05, p=.83. Despite declines over time, a group of ski areas had sustained high program use and active dissemination methods had sustained positive effects on GSS implementation.

Introduction

Sustainability of prevention interventions – continuation when external financial, organizational, and technical support has ceased (Nguyen, Gauvin, Martineau, & Grignon, 2005) – is essential for long-term change in health risk behaviors (Nguyen et al., 2005). Limited research exists on program sustainability (Dowda, James, Sallis, McKenzie, Rosengard, & Kohl, 2005; Nguyen et al., 2005; Rabin, Glasgow, Kerner, Klump, & Brownson, 2010). Administrative support, project manager characteristics and training, appropriate and modifiable program design, and close ties with other organizations facilitates sustainability (Dowda et al., 2005; Nguyen et al., 2005).

Go Sun Smart (GSS) (Scott, Buller, Walkosz, Andersen, Cutter, & Dignan, 2008), an effective occupational sun protection program (Andersen, Buller, Voeks, Walkosz, Scott, Cutter et al., 2008; Buller, Andersen, Walkosz, Scott, Cutter, Dignan et al., 2005), was disseminated to employers by the National Ski Areas Association (NSAA) in 2004-07 to protect outdoor workers who are at-risk for the development of skin cancer (Goodman, Bible, London, & Mack, 1995; Vishvakarman & Wong, 2003). A randomized trial evaluated NSAA dissemination compared to an enhanced strategy based on diffusion of innovations theory (DIT) (Rogers, 2003) that incorporated personal contacts. Active strategies can boost program fidelity (Fixsen, Blase, Naoom, & Wallace, 2009) which was essential, for dose-response effects of GSS were witnessed (Buller et al., 2005). The enhanced strategy produced greater GSS use at the immediate posttest (Buller, Andersen, Walkosz, Scott, Dignan, Cutter et al., 2010). In this paper, analyses comparing GSS use between the immediate and follow-up posttest and dissemination conditions are reported examining sustained program use over time and sustained impact of the enhanced strategy.

Methods

Sample and Setting

Sixty nine (n=69) U.S. and Canadian ski areas agreed to participate (53%; n=28 in 2004, 20 in 2005, and 21 in 2006) from 129 eligible ski areas in the NSAA membership (eligibility criteria: two or more aerial chair lifts; 100 or more employees; summit elevation of 2500 feet or higher; a full-time general manager; and did not participate in effectiveness trial). A priori, it was estimated that 60 ski areas would achieve 80% power with a 1-sided p-value. Ski areas were located in all regions except Midwestern United States and eastern Canada, ranged in size (200 to over 1000 employees), and were mostly privately owned. Randomization groups of ski areas that had no differences in ski area characteristics across dissemination strategy conditions (p>.05) (Buller et al., 2010).

Go Sun Smart Program

Twenty-three GSS materials were distributed. These included posters, small decals, magnets, outdoor signage, signage for ski/snowboard schools, brochures for employees and guests, training program, newsletter articles, and brief messages (see materials on Cancer Control PLANET [http://rtips.cancer.gov/rtips/programDetails.do?programId=308006]).

Intervention: Dissemination Strategies

Two dissemination strategies were compared. The “Basic Dissemination Strategy” (BDS) used by NSAA to distribute safety programs was applied to all ski areas. It included informational booths at annual and regional trade shows, promotional materials for GSS (e.g., logo-ed magnets, lip balm, and post-it notes), 1-page informational tip sheets, and free starter kits of materials (2 per year over 3 years in October/November and January). Managers could order additional GSS materials from NSAA.

The “Enhanced Dissemination Strategy” (EDS) added personal contact between project staff and senior managers to the BDS. During these contacts, staff highlighted need for occupational sun safety, obtained commitment to use GSS, helped plan for program implementation, and provided continued support for program use. These actions were based on principles of DIT and dissemination literature and were intended to reduce uncertainty about GSS by stressing the need for occupational sun protection and the program's fit with ski area operations, highlight the professional associations’ endorsement, secure public commitment from managers to use GSS, coach managers to use it, recruit internal champions to support GSS, and maintain commitment to use GSS (Buller et al., 2010; Fixsen et al., 2009; Rogers, 2003). Project staff visited each ski area once during November through January, met with the manager responsible for GSS, presented GSS to senior managers, and tried to identify internally champions for GSS. Staff made follow-up contacts by telephone and email at least monthly through March. Half of the ski areas received the EDS in addition to the BDS.

Experimental Procedures

Ski areas were recruited to a posttest-only two-group randomized trial. All ski areas received the GSS through the BDS in 2004-07; half were randomly selected by the project statistician after pretesting to receive the EDS (n=33 ski areas; 12 in 2004, 11 in 2005 and 10 in 2006). An immediate posttest observation of GSS use was performed in the ski season when ski areas were recruited and assigned to experimental condition. All employers continued to receive GSS for up to 2 years after the immediate posttest but the EDS was no longer used to support implementation. A long-term follow-up posttest of GSS use was performed 2 seasons later (n=27 ski areas receiving EDS in 2004) or 1 season later (n=41 ski areas receiving EDS in 2005-06 or 2006-07). All procedures were approved by the participating organizations’ Institutional Review Boards.

Observational Measure of Go Sun Smart Use

The outcome variable was a measure of the extent of use of GSS collected through on-site observations by 18 trained project staff in the immediate and long-term follow-up posttest (not all observers were blind to dissemination condition). The observational measure, modified from the effectiveness trial (Buller et al., 2005), produced a count of the number of GSS items observed to be in use (range=0 to 26). It was validated by independent trained blinded observers visiting 14 ski areas unannounced (Buller et al., 2010). All printed program materials on display (i.e., 15 posters/signs, 3 brochures, 2 static clings and 1 logo magnet) and any other sun protection messages (e.g., commercial advertising) were recorded. Observers searched all locations at the ski areas.

Statistical Analysis

GSS use was compared between the BDS and EDS across the immediate and long-term follow-up posttests in the 68 ski areas with complete assessments (n=33 EDS ski areas, n=35 BDS ski areas; 1 ski area was lost due to a lack of snow). Analyses were conducted using a mixed-model analysis in SAS Proc Mixed – two between-subjects factors of dissemination strategy (EDS v. BDS) and year of participation (Year 1 v. 2 v. 3) and one within-subjects factor of observation (immediate v. long-term follow-up posttest). There was no missing data in the observational measure; year of participation was not statistically significant indicating no difference between ski areas followed up at 2 or 1 year. Three covariates identified in the analysis of the immediate posttest (Buller et al., 2010), i.e., number of employees (reported by general manager), proportion of female senior managers (reported by general manager), and mean annual number of hours of sunshine (from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Satellite and Information Service), were included in the models. The comparison between conditions was performed using a 1-tailed p-value of 0.05, which was planned a priori, for it was expected that EDS would be at least as good as BDS and failure to reject the null hypothesis yield the same conclusion as inn a 2-tailed test, i.e., employ the BDS.

Results

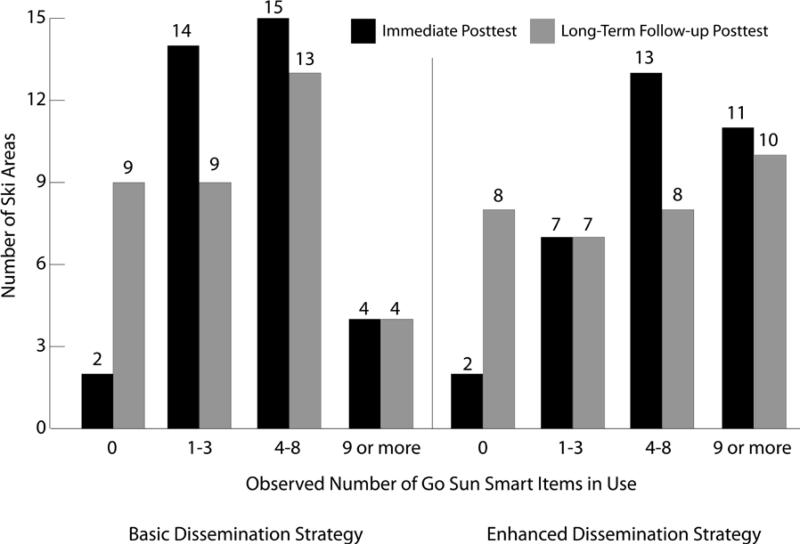

Use of GSS was variable across ski areas (Table 1); however, use declined from the immediate to the long-term follow-up posttest, Observation F[1,62]=6.95, p=.01. While 17 ski areas used none of GSS at the long-term follow-up, 14 ski areas were still using 9 or more items (compared to 15 ski areas were using 9 or more items at the immediate posttest). Thus, there was evidence of both a decline in use but also of a group of sustained high implementing ski areas. The beneficial effect of EDS also was sustained, with elevated use at both posttests (Table 1), Dissemination Strategy F(1,62)=5.75, p=0.02; Dissemination Strategy x Observation F(1,60)=0.05, p=.83. Finally, none of the four covariates in the overall model moderated GSS sustainability (p>.05 for all two-way and three-way interactions among covariates, dissemination strategy, and observation)

Table 1.

Unadjusted mean Go Sun Smart use (standard deviation) at ski areas in North America at immediate and long-term follow-up posttests in 2004-2008 by Basic and Enhanced Dissemination Strategy and posttest observation

| Observation | BDS (n=35 ski areas) | EDS (n=33 ski areas) | Total (n=68 ski areas) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immediate posttest | 5.17 (4.67) | 7.36 (5.58) | 6.24 (5.21) |

| Long-term follow-up posttest | 3.80 (4.51) | 5.70 (5.59) | 4.72 (5.12) |

| Total | 4.49 (4.61) | 6.53 (5.61) | 5.48 (5.20) |

Discussion

The data suggested that GSS was sustained by a number of ski areas and that the superiority of EDS to achieve program used continued. This finding is important because other analyses showed that employees at the immediate posttest had greater program exposure when ski areas used more GSS items. In turn, employees’ sun protection behavior improved when nine or more items were in use (Buller, Andersen, Walkosz, Scott, Dignan, Cutter et al., 2011), a level of use maintained by 20% of the ski areas at the long-term follow-up posttest.

Still, GSS use declined over time and low implementers (under 9 items) at immediate posttest in particular were most likely to decline or discontinue program use. This implies that it is essential to achieve high initial use of the program to product sustainability. This might be achieved by adding more reminders, providing testimonials from high implementers, including sun safety in policy statements from professional associations, writing occupational sun protection into workplaces policies, and having workers compensation insurers recommend occupational sun protection.

Like this study, other skin cancer prevention interventions have shown promising sustainability in short follow-ups (Hill, White, Marks, & Borland R., 2002; Stock, Gerrard, Gibbons, Dykstra, Weng, Mahler et al., 2009). Some researchers, though, have suggested that sustainability should be evaluated 3-5 years after active support ends to provide time for maintenance, degradation, capacity building, and other sustainability indicators (e.g., organizational changes) to emerge (Goodman et al., 1995). Hence, the shorter follow-up used in this study may have overestimated program sustainability and later follow-up is advisable. Beyond, the short follow-up period, the study was limited by being conducted in single industry, during winter outdoor recreation, and in eastern, southern, and western North America. There were also a number of strengths in the trial, such as observational measures, randomization, a large sample of employers, and partnerships with professional associations. (Buller et al., 2010).

Implications for Theory and Practice

Multi-model dissemination strategies with active contact have been successful elsewhere (Rabin et al., 2010) and the sustained effect of the EDS in this trial provides further argument for their use, despite their increased cost (Buller et al., 2010). It is not clear from this trial which principles in EDS were most responsible for sustainability. Research on program implementation has identified training, ongoing coaching and support, and facilitative administration (i.e., staff worked to obtain public commitment to use GSS and fit it into ski area operations) as core implementation components, all of which were included in the EDS (Fixsen et al., 2009). Also, the importance of professional association endorsement must not be discounted for its ability to provide access, credibility, and communication channels (Dearing, Maibach, & Buller, 2006). Future studies need to identify the mechanisms that most contribute to sustained dissemination.

Some decline in GSS use was not surprising because managers had discretion in when, how, and how much of the program was used. Managers often change or re-invent programs, combine or create new program components, and change the work environment when rolling out programs to address organizational interests, needs, or circumstances (Dearing et al., 2006; Rogers, 2003). Hopefully these adaptations produce an optimal intervention with high “external validity” (Dearing et al., 2006). Managers also may implement principles for promoting occupational sun protection evident in GSS (i.e., evidence-based practices) while not using its materials (i.e., evidence-based program). Program use should be assessed with a variety of measures and stakeholders to determine what is used, to what extent, and why.

Several lessons have emerged from the GSS effort. Partnerships with industry professional associations are a promising means of successful immediate and sustained dissemination to reach outdoor workers at high risk for chronic sun exposure. Successful strategies are most likely to be built on sound health behavior change principles and should consider incorporating active contact with intermediary organizations to promote and support program implementation. Dissemination of occupational sun safety programs should contribute to a healthy workforce which can be beneficial to employees’ satisfaction and performance, employers’ bottom line, the company's corporate citizenship image, and ultimately the population's health.

FIGURE 1.

Observed number of Go Sun Smart items in use by Basic and Enhanced Dissemination Strtegy at Immediate and Long-term Foolow-up Posttests

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (CA104876). The National Cancer Institute was not involved in the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, preparation of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The authors wish to thank the National Ski Areas Association, Professional Ski Instructors of America, American Association of Snowboard Instructors, and the National Ski Patrol for their support, and the senior managers at 69 ski areas who made their operations available to us.

Biography

David Buller is a Senior Scientist and Director of Research at Klein Buendel, Inc., a health communication and media development firm in Golden, Colorado.

Barbara Walkosz is a Senior Scientist at Klein Buendel, Inc.

Peter Andersen is a Professor (Emeritus) in the School of Communication at San Diego State University.

Michael Scott is President of Mikonics, Inc. in Auburn, California.

Mark Dignan is a Professor in the Department of Internal Medicine and the Markey Cancer Center at the University of Kentucky.

Gary Cutter is a Professor in the Department of Biostatistics at the University of Alabama, Birmingham.

Xiao Zhang is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Biostatistics at the University of Alabma, Birmingham.

Ilima Kane is a Senior Project Manager at Klein Buendel, Inc.

Contributor Information

David B. Buller, Klein Buendel, Inc.

Barbara J. Walkosz, Klein Buendel, Inc.

Peter A. Andersen, San Diego State University

Michael D. Scott, Mikonics, Inc.

Mark B. Dignan, University of Kentucky

Gary R. Cutter, University of Alabama, Birmingham

Xiao Zhang, University of Alabama, Birmingham

Ilima L. Kane, Klein Buendel, Inc.

Reference List

- Andersen PA, Buller DB, Voeks JH, Walkosz BJ, Scott MD, Cutter GR, et al. Testing the long term effects of the Go Sun Smart worksite sun protection program: A group-randomized experimental study. Journal of Communication. 2008;68:447–471. [Google Scholar]

- Buller DB, Andersen P, Walkosz BJ, Scott M, Dignan M, Cutter G, et al. The effect of program implementation on occupational sun protection when disseminating an evidence-based occupational sun protection program.. Abstract presented at the annual meeting of the Society of Behavioral Medicine.; Washington, D.C.. 2011, April. [Google Scholar]

- Buller DB, Andersen PA, Walkosz B, Scott M, Dignan M, Cutter G, et al. Effective strategies for disseminating a workplace sun safety program.. Abstract presented at the annual meeting Society of Behavioral Medicine.; Seattle, WA. 2010, April. [Google Scholar]

- Buller DB, Andersen PA, Walkosz BJ, Scott MD, Cutter GR, Dignan MB, et al. Randomized trial testing a worksite sun protection program in an outdoor recreation industry. Health Education & Behavior. 2005;32:514–535. doi: 10.1177/1090198105276211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dearing JW, Maibach E, Buller D. A convergent diffusion and social marketing approach for disseminating proven approaches to physical activity promotion. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2006;31:S11–S23. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowda M, James F, Sallis JF, McKenzie TL, Rosengard P, Kohl HW. Evaluating the sustainability of SPARK physical education: A case study of translating research into practice. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport. 2005;76:11–19. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2005.10599257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fixsen DL, Blase KA, Naoom SF, Wallace F. Core implementation components. Research on Social Work Practice. 2009;19:531–540. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman KJ, Bible ML, London S, Mack TM. Proportional melanoma incidence and occupation among white males in Los Angeles County (California, United States). Cancer Causes Control. 1995;6:451–459. doi: 10.1007/BF00052186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill D, White V, Marks R, Borland R. Changes in sun-related attitudes and behaviors, and reduced sunburn prevalence in a population high risk of melanoma. In: Hornik RC, editor. Public health communication. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2002. pp. 163–178. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen MN, Gauvin L, Martineau I, Grignon R. Sustainability of the impact of a public health intervention: Lessons learned from the laval walking clubs experience. Health Promotion Practice. 2005;6:44–52. doi: 10.1177/1524839903260144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabin BA, Glasgow RE, Kerner JF, Klump MP, Brownson RC. Dissemination and implementation research on community-based cancer prevention: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2010;38:443–456. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations. 5th ed. Free Press; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Scott MD, Buller DB, Walkosz BJ, Andersen PA, Cutter GR, Dignan MB. Go sun smart. Communication Education. 2008;57:423–433. doi: 10.1080/03634520802047378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stock ML, Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Dykstra JL, Weng CY, Mahler HI, et al. Sun protection intervention for highway workers: Long-term efficacy of UV photography and skin cancer information on men's protective cognitions and behavior. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;38:225–236. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9151-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vishvakarman D, Wong JC. Description of the use of a risk estimation model to assess the increased risk of non-melanoma skin cancer among outdoor workers in Central Queensland, Australia. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2003;19:81–88. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0781.2003.00012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]