Abstract

Purpose:

Relative to the overall population, older adults consume a disproportionally large percentage of health care resources. Despite advocacy and efforts initiated more than 30 years ago, the number of providers with specialized training in geriatrics is still not commensurate with the growing population of older adults. This contribution provides a contemporary update on the status of geriatric education and explores how geriatric coverage is valued, how geriatric competence is defined, and how students are evaluated for geriatric competencies.

Design and Methods:

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with curriculum representatives from 7 health profession disciplines in a case study of one academic medical center.

Findings:

Geriatric training varies across health professions’ disciplines. Although participants recognized the unique needs of older patients and valued geriatric coverage, they identified shortage of time in packed curricula, lack of geriatrics-trained educators, absence of financial incentive, and low student demand (resulting from limited exposure to older adults and gerontological stereotyping) as barriers to improving geriatric training.

Implications:

Progress in including geriatric training within curricula across the health professions continues to lag behind need as a result of the continuing presence of barriers identified several decades ago. There remains an urgent need for institutional commitment to enhance geriatric education as a component of health professions curricula.

Keywords: Geriatric education and training, Barriers, , Institutional commitment

In the United States, persons 65 years of age and older utilize a disproportionately high share of health care services, and with the continuing growth of this population, this proportion is expected to continue to grow (National Center for Health Statistics, 2010). Yet the provision of health professionals with expertise in geriatrics and gerontology continues to lag significantly behind need. (Throughout this article, we primarily use the term geriatrics. In this context, our commentary also embraces nonmedical and nonclinical aspects of the process of aging and health often considered under the rubric of gerontology.) This situation was anticipated almost 50 years ago by Kastenbaum (1963), who identified the “reluctant therapist” (health practitioners’ reluctance to provide care to older adults) as a significant barrier to developing an adequate geriatrics workforce.

The first geriatric residencies were developed in the early 1970s (Libow, 1976), and the need for geriatric education was reinforced in the late 1970s and early 1980s in reports emanating from the Association of American Education Colleges (1983), Institute of Medicine (1978), and Elster (1985). Such reports were complemented by a series of studies and initiatives designed to foster the development of a well-trained health care workforce capable of dealing with the health needs of an aging population (Begala, 1980; Birenbaum, Aronson, & Seiffer, 1979; Panneton & Wesolowski, 1979). The call for geriatric education was echoed in related health professions fields (Pratt, Simonson, & Lloyd, 1982). But by 1986, Edward L. Schneider and his colleague, T. Franklin Williams (Director of the National Institute on Aging), ruefully noted that “Despite these calls for the introduction of geriatrics and gerontology into the medical education system, we have failed to respond” (p. 432). Although almost 75% of medical schools in the United States offered elective courses in geriatrics, only 4% of medical students chose to pursue these options, and medical schools only had about 10% of the faculty needed to teach geriatrics. In their editorial, “Geriatrics and Gerontology: Imperatives in Education and Training,” they called for increased focus on and support to ensure that “sufficient numbers of persons will be trained to provide for the future needs of our aging population” (Schneider & Williams, 1986, p. 434). In doing so, they reiterated many of the barriers to achieving this objective that, even by 1986, had been cited for decades, including lack of curricula, few trained faculty and educators to implement geriatric training programs, the absence of incentives for developing such training, and limited interest by students, frequently associated with aversion to working with geriatric populations. Twenty-five years later, have we answered the call?

Contemporary Status of Geriatric Education

In assessing how the situation has changed since 1986, we focus on seven health profession disciplines: Medicine, Nursing, Pharmacy, Dentistry, Physician Assistant Studies, Physical Therapy (PT), and Communications Disorders. We have tried to locate the most recent data available pertaining to the extent of geriatric training. Some of the research included in this section is necessarily somewhat dated due to the absence of more contemporary information.

Despite the diverse range of knowledge and skills required to appropriately care for older adults, the median time devoted to geriatric education in medicine in 2005 was still only 9.5 hours (Eleazer, Doshi, Wieland, Boland, & Hirth, 2005). A survey of medical schools in the United States revealed that less than half (41%) of responding schools have a structured geriatrics curriculum and less than a quarter (23%) require a geriatric clerkship (Geriatrics Workforce Policy Studies Center, 2008). The American Association of Medical Colleges has created minimum competencies in geriatrics for medical students (Portal of Geriatric Online Education, 2010). Specifics for how these competencies are developed and evaluated are determined by individual schools (Kuehn, 2009). As a result, there is often ambiguity regarding the extent to which competencies are addressed. Many medical students believe they receive inadequate coverage of geriatrics (Association of American Medical Colleges, 2010). Currently, there are only 1.7 geriatricians for every 10,000 adults aged 65 years and older, with this ratio expected to decline in the future (Administration on Aging, 2010; American Geriatrics Society Geriatrics Workforce Policy Studies Center, 2011). Given that older adults average 27% of all physician office visits (6.3 visits per year; Pfizer, 2007), the critical remaining need for geriatric training is evident (Cherry, Lucas, & Decker, 2010).

There is a similar shortage of gerontological content within U.S. nursing curricula. The American Association of Colleges of Nursing, in partnership with the John A. Hartford Foundation Institute for Geriatric Nursing (2000), has created core geriatric nursing competencies. Current nursing licensure tests also now include some gerontological content. Yet, even though 63% of newly licensed nurses report that older adults comprise a majority of their patient loads (Wendt, 2003), a 2004 survey of U.S. undergraduate nursing programs suggested that more than 85% did not require any gerontological coursework (Grocki & Fox, 2004). More recent research suggests that only one third of baccalaureate nursing schools and only 20% of associate degree nursing programs report a stand-alone geriatrics course (Berman et al., 2005; Ironside, Tagliareni, McLaughlin, King, & Mengel, 2010). This limited geriatric didactic content is congruent with findings from a survey of nurse practitioners in which the majority of the respondents reported that they were only somewhat comfortable caring for older adults, particularly in terms of disease management and psychosocial issues (Scherer, Bruce, Montgomery, & Ball, 2008).

A discrepancy also exists between need and existing geriatric coverage in pharmacy education. A 2003 survey revealed that all responding pharmacy schools had some geriatric education in their curriculum, but the extent of such training was not commensurate with the growing older adult population (Dutta et al., 2005). A 2006 survey revealed that although all pharmacy programs had practice experience options in geriatrics or long-term care, only 43% reported the option of an elective geriatrics course (Odegard, Breslow, Koronkowski, Williams, & Hudgins, 2007). Given that 26% of older adults use five or more prescription medicines (Pfizer, 2007) and that many older adults receive inappropriate medications (Barnett et al., 2011), the need for enhanced geriatric expertise is apparent. Although older adults are the largest consumer group of prescription and over the counter medications (Phillips, 2011), less than 1% of pharmacists have geriatric certification (Gray, Elliott, & Semla, 2009). Competencies addressing particular populations, including older adults, are not always assessed in the pharmacy licensure examination, though some exams will include relevant questions (National Association of Boards of Pharmacy, 2010).

Dentistry lacks geriatric competency guidelines established by a national advising board. To address this, suggestions have been made to include geriatric-based knowledge and skills, such as psychosocial awareness, communication, and treatment concerns that are more common among older patients (Dolan & Lauer, 2001). All dentistry programs in the United States self-report teaching at least some aspect of geriatric dentistry and 67% report clinical geriatric training, though the clinical component is not always required (Mohammad, Preshaw, & Ettinger, 2003). Paradoxically, although only 14.3% of graduating dental students consider themselves to be well prepared to provide geriatric oral health care, just 16.3% believe insufficient time was devoted to training and education in geriatric dentistry (Okwuje, Anderson, & Valachovic, 2009).

Physician Assistants (PAs, specially trained persons certified to provide basic medical services [including diagnosis and treatment of common ailments], usually under the supervision of a licensed physician; Physician Assistant, 2011), spend one third of their time with older patients (Hachmuth & Hootman, 2001). As early as 1988, one study found that half of the PA programs in the United States incorporated geriatric content through dedicated formal lectures, one third incorporated geriatric content via discussion of related topics, and less than 10% reported no geriatric offerings (Curry, Fasser, & Schafft, 1988). Despite this more positive scenario, Olson, Stoehr, Shukla, and Moreau (2003) found that a national sample of PA program directors believed there was a need for even more didactic and clinical time devoted to geriatrics. The Accreditation Review Commission on Education for the PA now mandates clinical experience in geriatrics, instruction in the physical examination and normal psychological development of older patients, and consideration of end-of-life issues (Brugna, Cawley, & Baker, 2007).

In PT education, there is long-standing recognition of the importance of focusing on older adults; by 1987, aging content was incorporated into required courses (Granick, Simson, & Wilson, 1987). Although most schools include aging content in existing courses, only 10% offer a formal geriatrics course (Center for Health Workforce Studies, 2006). Although the national PT licensure examination focuses primarily on general competence, it also includes some explicit geriatric content (Federation of State Boards of Physical Therapy, 2007).

Required competencies in communication disorders (CD, which embraces audiology and speech–language) focus on lifespan expertise and effective skills for serving all ages (American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, 2010a, 2010b). We were unable to find any literature reporting the extent to which these programs currently include specifically designated gerontological content.

Limited gerontological training in many health care disciplines suggests that health professionals are inadequately prepared to address the needs of the older adult population. Although all programs in nursing and medicine require pediatrics rotations, the same is not yet true with respect to geriatrics rotations (Kovner, Mezey, & Harrington, 2002). The reason for this discrepancy is unclear, particularly given evidence that having geriatric competency improves patient outcomes (Cohen et al., 2002; Kovner et al., 2002; Phelan, Genshaft, Williams, LoGerfo, & Wagner, 2008). There is also the potential for significant cost savings with high-quality geriatric care.

Many programs cite packed curricula as a challenge when faced with the prospect of adding additional material (Saunders, Yellowitz, Dolan, & Smith, 1998). Other challenges include few faculty members with geriatric expertise and significant competing clinical practice obligations among these faculty, leaving limited time for student education (Warshaw, Bragg, Shaull, & Lindsell, 2002). A program is more likely to offer geriatric-focused courses if geriatrics is a primary interest for one of the faculty members (Pratt, Simonson, & Boehne, 1987). Opportunities for developing geriatric expertise are limited by few resources to support training, low reimbursement rates for geriatric care, and the belief that caring for older adults does not require distinctive geriatric skills (LaMascus, Bernard, Barry, Salerno, & Weiss, 2005; Rubin, Stieglitz, Vicioso, & Kirk, 2003).

Although we focus specifically on the status of geriatric education in the United States, the need for geriatric education and expertise and the challenges to incorporating geriatric training are not unique to the United States. For instance, a study of geriatric dentistry education in Europe found that 7% of schools responding to a survey did not teach any aspect of geriatric dentistry and 39% lacked any clinical geriatric component (Preshaw & Mohammad, 2005). Another study found that for Nurse Practitioner and Advanced Practice Nurse educational programs, only 13 of the 21 countries surveyed included geriatric training (Pulcini, Jelic, Gul, & Loke, 2010). A review of geriatric medical education in Europe found that not only were programs variable in their inclusion of geriatric content but also such content was often poorly developed, suggesting a potential need for significant educational restructuring to meet the geriatric educational imperative (Cherubini, Huber, & Michel, 2006).

Although the data presented here suggest that the status of geriatric education has improved compared with the time of Schneider and Williams’ lament, we are concerned that these initial improvements have not resulted in the depth and breadth of training needed and may have led to complacency and waning interest in further enhancing geriatric education (Gazewood, Vanderhoff, Ackermann, & Cefalu, 2003). Acknowledging this concern, the purpose of this study was to evaluate how geriatric coverage is currently valued, how geriatric competence is defined, and how students are evaluated for these competencies in one academic health care center. The intent was to use a case study to cast light on current actions, beliefs, attitudes, and perceptions regarding geriatric education as part of an appraisal of the degree to which the future holds the promise of a health care workforce that is better trained to address the needs of an older population.

Design and Methods

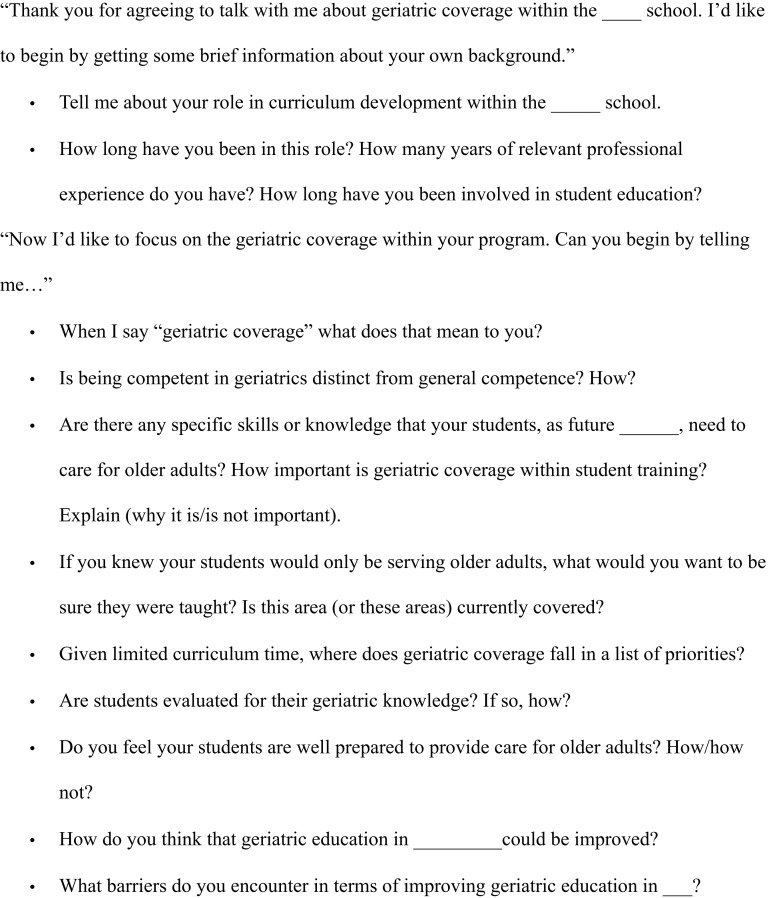

We chose to focus on educational training programs, rather than residency or fellowship opportunities. The Dean for each program was asked to identify the three most influential people with regard to curriculum development within each of the seven programs. If any of these individuals was unable or unwilling to participate, then the Dean was asked to identify the next person with the most influence on curriculum until a total of three participants were identified and recruited for each discipline. Participants were engaged in semi-structured interviews (Figure 1). All protocols were approved by the University of Kentucky Institutional Review Board.

Figure 1.

Interview script and guide.

Interview length ranged from 10 to 45 minutes, with most lasting approximately 30 minutes. All interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were read, re-read, and checked for accuracy. A three-stage process of constant comparative analysis was employed by two independent coders. Line-by-line open coding was followed by axial coding to group codes according to categories and properties (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). Finally, central themes in each interview were identified by collapsing categories using selective coding (Glaser & Strauss, 1967; Strauss & Corbin, 1990). Direct quotes were identified to convey the essence of each theme (Merriam, 1988). To enhance the rigor and accuracy of the findings, the information presented in Table 1 regarding geriatric coverage in each of the programs was sent back to each of the participants for confirmation.

Table 1.

Geriatric Content and Evaluation in the Health Professional Programs

| Communication disorders | Dentistry | Medicine | Nursing | Pharmacy | Physical therapy | Physician assistant | |

| Stand-alone geriatric coverage | |||||||

| Required didactic | x | —a | x | x | |||

| Required clinical rotation | x | x | |||||

| Elective offered | n/a | x | x | n/a | n/a | ||

| Gerontology certificate participation | x | x | |||||

| Format of geriatric content | |||||||

| Didactic | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Clinical | x | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Experiential | x | x | x | —b | x | x | |

| Mentor | x | ||||||

| Evaluation components | |||||||

| Course exams | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Assignments | x | x | —b | x | x | ||

| Clinical feedback | x | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Standardized patients | x | x | x | x | |||

| Content on boards/licensure exams | x | —c | x | —c | x | x |

Notes: All programs had integrated didactic and clinical geriatric content. Boxes are checked if any of the three participants mentioned that item. n/a = not applicable.

Integrated (though explicitly assessed).

For those in the geriatric elective only.

May be included through cases on boards.

Findings

Sample

Participants held different roles relevant to curriculum development and implementation, including Course Director, Director of Graduate Studies, Academic/Education Dean, Curriculum Committee Member, and Chair/Program Director. The 12 female and 9 male participants were experienced professionals and educators, with an average of 29 years of relevant professional experience (range 10–41) and an average of 25 years involvement in student education (range 8–36).

Geriatric Coverage

A distinction was made between inclusion of geriatric content as a component of general education and focused geriatric instruction. Representatives from each program mentioned integrating geriatric issues throughout coursework. Three programs offered stand-alone didactic geriatric courses (Table 1). Although representatives of all programs mentioned that students interacted with older adults in clinical settings, the nursing and PA programs were the only ones with a required, dedicated geriatric clerkship. Participants from two programs mentioned offering a geriatric elective and two programs mentioned that some students participate in the university’s gerontology certificate program. In addition to didactic and clinical coverage, five programs created experiential assignments to integrate geriatric content. For example, one program fostered elder–mentor relationships where students partnered with older adults to complete course assignments.

How Is Geriatric Coverage Valued?

In responding to this question, participants commented on the growing older adult population. A dentistry participant observed:

We’re gonna have more elders than we ever had in a very short time and the students we have right now are going to have more elders in their practice than we had in our practice, and so it’s the smart thing to do to prepare them for that.

One PT participant commented:

I think it should be a higher priority than it actually is, but I think we’re moving in that direction and again, I just think the Baby Boomers are going to re-write priorities for the medical world.

The importance of geriatric education was also recognized in relation to disproportionate use of health care services.

Especially with us being an aging population and because the older population uses the majority of prescription and nonprescription medications, I think from a pharmacy perspective and for pharmacy curriculum it should be [valued] much higher because that [population] is such a big user of medications. (Pharmacy participant)

Many participants recognized that regardless of specialty, each student’s future employment would involve older adults through interaction with older patients and caregivers. One PA participant expressed how geriatric expertise partially reflected self-interest,

I’m getting there [older]; you’re getting there, too. We’re all hoping to successfully reach that point in our lives, and we all recognize the unique, the changing needs of that population.

A CD faculty member emphasized that geriatrics is important because we all benefit, “We owe it to all of us to do the best we can for quality of life from the beginning to the end.”

Recognition of the need to acquire specific skills and knowledge required to treat older adults also made geriatric training important. Competence in geriatrics was differentiated from general competence. As one CD participant explained, “A general competence in the field does not necessarily mean that you have all the training and competence that you need in the older population.” A pharmacy participant elaborated, “You can’t develop their (students’) appreciation, and hands-on training, and comfort zone, and competencies, and abilities, and skills, and all those things if you don’t have (geriatric) practice and exposure.”

An economic rationale was also provided for the value of geriatric training. A participant from medicine indicated that without appropriate geriatric expertise, patients would experience more adverse events, resulting in greater utilization of health care resources, “There’s probably a strong economic argument to be made, above and beyond the obvious ethical and care-based arguments.”

Beyond the underlying philosophical rationale for valuing geriatric education, participants indicated that demands of accreditation bodies, which often mandate geriatric competence, provided strong impetus for incorporating geriatric content into the curriculum. Geriatric content is currently not required by medical accreditation standards except as a thread throughout the curriculum. A medicine participant noted that if geriatric content were required for accreditation, “That puts it on every school’s radar map; if it gets carved out as a specific standard … . In our current system it’s not going to get in because it doesn’t reach that threshold of being on boards.”

Even when outside bodies require geriatric competence, the manner in which this competence is achieved and the extent to which geriatrics becomes a curriculum focus is often left to the individual program.

We have our standards for national certification that we work on with our students that are outcomes based. The outcomes specify clinical [expertise], both skill and knowledge, in a variety of disorders across the lifespan. So we do that and we say we do that. Do we specifically have any evaluation forms that look at whether somebody works with geriatrics? No, I don’t think we do. Do we assure that every student who goes through this program has an experience with a geriatric population? No, I don’t think we do. The stance that the programs in general have to take is that we are giving people the basic information they need and a lot of the other stuff. The age or the work setting specific stuff has to come during a clinical fellowship year, that’s the first year of paid employment, or through continuing education. (CD participant)

Similarly, a dentistry participant expressed how meeting accreditation standards in geriatrics differs by institution:

[Accreditation] does talk about the different age groups, it says “must be able to manage child, adolescent, adult, geriatric patients” … . They want to see evidence that the students are seeing geriatric patients. But they don’t have numbers, they don’t say every student must see this many, but the idea is that the students, when they graduate, are deemed competent to do procedures or to manage patients in all age groups.

Finally, the presence of individual faculty member proponents remains a prominent influence on geriatric content in the curriculum. Absence of an advocate made infusing geriatric content into the curriculum more of a challenge. A CD participant spoke about how her program would benefit from a faculty member with geriatric expertise,

It would be helpful if we had one person who had a strong background … there are none of us who have, who claim that as our area of expertise … nobody who says, “That’s my thing, and that’s what I really want to give students a passion for.”

How Is Geriatric Coverage Defined?

Participants distinguished geriatrics and general competency in their comments on how geriatric content was defined. A PT participant recalled telling her students, “Don’t treat older adults just like older young people” and urging them to acknowledge that older adults “have special things going on that make them unique.” A PA participant drew the parallel that just as children are not small adults, older adults are not just old middle-aged adults.

When asked to discuss the distinctive qualities of geriatrics, participants mentioned the need to understand age-related sensory and cognitive deficits and appropriate communication strategies to accommodate these declines, recognition of diseases more common with aging, the prevalence of problems with polypharmacy, unique contextual psychosocial–environmental factors, understanding prejudicial attitudes toward older adults, and the need to negotiate distinctive features of Medicare reimbursement. A medicine participant said,

There are a set of unique problems as well as physiologies associated with the geriatric population that are not directly or readily generalizable from the others … geriatrics becomes unique … in bio-psycho-social; it’s bio-unique, psycho-unique, and social-unique.

A dentistry participant expressed similar sentiments:

There are certain procedures, whether you do them on an adolescent versus someone who’s a geriatric, mechanically they’re the same, but in terms of management of the patient, on every level that you can think of, there are big differences between a child, an adolescent, a relatively young and healthy adult, and a geriatric patient.

Many participants commented that treatment of geriatric patients is distinctive in the need to address complex sociocultural and contextual needs and focus on the unique circumstances of each patient, modifying disease specific treatment guidelines to achieve holistic care.

A few participants commented that older adults represent a different culture and that the development of a “cultural competence” is warranted within health care training.

It’s like cultural competency, being able to communicate effectively with someone who may be generationally different than the practitioner … . A lot of the folks that we are training don’t have a lot of experience with elders. Their parents might have experience with their grandparents, but most people in dental school that we’re training haven’t necessarily seen the whole life cycle. They may know their grandma and grandpa but they may not have all those challenges. (Dentistry participant)

Elaborating on this theme, other participants noted challenges in developing cultural competency given generational differences and limited intergenerational exposure. Some mentioned that students may initially have anxiety regarding older patients due to limited interactions with this age group prior to enrolling in their professional programs. A few participants believed that if students had stronger relationships with grandparents, they might have an easier time developing this competence. One CD participant reported that the lack of common historical and cultural reference points makes elder patient–provider interactions more challenging,

The events that are salient for geriatric people are not salient for young people and that’s who’s actually going out and working with them … and that certainly doesn’t mean a young person couldn’t reflect that competence, but I think they have to have some special training, and they need to do a few things in order to make the connection.

There was clear recognition of the need for an interdisciplinary perspective and collaboration in training for geriatric care.

With this group (older adults) particularly … often there are more systemic problems, more medications, just a lot of other factors going on and it would be really important to be able to work with a team, not dentists over here and the physician over there, for us to work as a team. (Dentistry participant)

A medicine participant also stressed interdisciplinary awareness, indicating “you would need to be very aware of what’s available (other providers) and what’s there because that’s going to affect your rehabilitation.” A PT participant commented, “One of the things we don’t do as well as we could at this university is share information with each other.” Reflecting this theme, a CD participant, aware of gerontology courses available on campus, indicated that his program has not found a way to take advantage of these resources.

How Is Geriatric Content Evaluated?

Approaches to evaluating geriatric competency varied. Measures employed by various programs included questions on regular tests, feedback provided to trainees during clinical rotations, older adult patient simulations, standardized patient evaluations, and written personal reflections on experiences with older adults (see Table 1). Explicit geriatric content assessment also varied across disciplines. Four of the programs conducted studies that, at least in part, evaluated geriatric coverage. One nursing participant expressed how, “we always have to be cognizant of the elderly piece because it’s integrated.” Another emphasized that the integration approach requires vigilance to assure geriatric content in every course.

Barriers to Including Geriatric Content

Analysis of the transcripts revealed an acute awareness of barriers that prevent the full integration of geriatric content in health sciences programs. Time was the most frequently reported barrier. One CD participant stated, “It would be easy for me to say, ‘Oh, yes, we should add a whole course on aging to our curriculum.’ The rest of the faculty would probably yell and scream as to where are we going to fit this”. Participants across disciplines discussed the difficulty of incorporating new interests into already packed curricula.

When you add something, what do you take away? We can’t keep adding. That’s one of the challenges we face … . You think we’re doing a good thing by continuing to add, and you might say, ‘add all this geriatric stuff,’ but it makes the students more tired and eventually it compromises learning. (Pharmacy participant)

A nursing participant likened this problem to a loaded baked potato, noting that if too many toppings are added, things will fall out. Trying to cram in too much content may result in students failing to retain essential concepts. In programs with accrediting body geriatrics requirements, time may be a challenge but this cannot preclude including geriatric content.

A second frequently mentioned barrier was the scarcity of educators with specialized geriatric training. “We’re always looking for more geriatricians in true geriatric practices,” noted one PA participant. Faculty with geriatric knowledge and experience are critical for infusing geriatric content within the curriculum and providing appropriate supervision in clinical settings. They are also valuable advocates for geriatrics. A medicine participant explained,

Curricula change depends on the resources you have available. So if your curricula change people are in internal medicine, you have a chance of getting this, but if there aren’t any geriatricians or it’s very few or they’re focused on another specialty, then that’s going to be what’s emphasized.

Without an advocate there is no push for geriatric coverage, and without geriatric content, interest in pursuing geriatrics remains low and the scarcity of geriatricians is exacerbated. The solution to this self-perpetuating cycle, this participant suggested, lies in health policy that provides economic incentives for geriatric specialization.

The important role of financial incentive was reinforced by a dental participant who observed that:

The elephant in the room, the kind of the obvious thing that people don’t like to talk about, is the fact that you don’t get a lot of money from folks that are functionally dependent in nursing homes. That’s always an issue, reimbursement; how can you keep something like this sustainable? So that’s the problem with geriatrics and dentistry. At least with medicine you have Medicaid and Medicare, but in dentistry there’s no Medicare reimbursement and Medicaid is very little … . That then answers the question why it isn’t much higher priority. And I think because it fails to be something that reimburses very well. It’s why a lot of dentists quite frankly don’t go into it, they kind of stay away from the area.

A third barrier to comprehensive integration of geriatric content in health sciences programs was the nature of geriatric exposure within most programs. A PT participant explained, “I don’t think most students get the opportunity to see healthy people living in the community next door. And that’s sad … . They see people when they are really sick in the hospital.” This participant highlighted the pervasive nature of gerontological stereotyping among health care students and the need to have them become aware of a healthy old age as an achievable goal for many older adults. A nursing participant echoed this sentiment,

There’s lots of elders out there that are really doing fine. They are active and they are very engaged in life, and so I would want to make sure they [the students] saw that side of it, this is possible, this is what you want to get to, here are the things you need to do to help preserve that and help people achieve that quality of life.

Several participants noted that it is a struggle to identify locations where they can expose students to older adults without turning them off from working with this population.

The primary barrier is assuring that you get a quality place, because, you know as well as I do, some long-term care facilities are good experiences and some of them are terrible experiences for students … . We’ve had students … who have come away and say, “I wouldn’t go near one of those places again if you paid me” and I think it has to do with the quality of experience they’re having. (CD Participant)

A nursing participant explained that her program no longer took students into nursing homes because they were perceived as “too depressing.”

A final and closely related barrier to the adequate incorporation of geriatric content in the curriculum was lack of student interest. This was perceived to stem from limited exposure to healthy older adults. As a nursing participant explained,

Kids live far away from their grandparents … . They’re just not around elderly people and it’s not what they’re so interested in … the geriatric people they do work with are sick, and something’s wrong, and then, of course something’s wrong because they’re 87.

This participant suggested that enthusiasm for working with older adults might be improved by emphasizing the variety of career options. One dentistry participant expressed how a passion for working with older adults leads people to consider geriatric dentistry,

The folks who gravitate towards, say, making full dentures, prosthodontics … they really enjoy their interactions with those patients. And that’s why they go into it. It’s not so much that they like making dentures or partials, they like the age group … there are a lot of dentists who just say, it’s the most rewarding thing and that’s why they want to specialize in that because they like the average age of their patients.

Where From Here?

Our case study of one academic medical center confirmed that geriatric coverage in current health sciences educational curricula remains limited despite clear recognition of need. Although progress is being made in some health science disciplines, participants from all seven disciplines represented in this study indicated that there is a need for still greater infusion of geriatric content into curricula. Geriatric education is considered invaluable, but barriers to improving the situation that have existed for decades remain remarkably resilient. Although the specific details of our case study findings may not be generalizable to other academic medical centers, we strongly suspect that a similar overall pattern of inconsistent and inadequate coverage would emerge from parallel studies to our own, even with attention to other health-related disciplines such as psychology and social work. We emphasize that our study focused on faculty perceptions. We did not explore student perspectives nor did we directly evaluate the substance and quality of specific geriatric curricular content or curricular outcomes. Even with these limitations, several conclusions can be drawn.

The main contemporary impetus for inclusion of geriatric content into the curriculum appears to be twofold: the need to meet accreditation standards (something that seems to have assumed increased importance in recent decades) and the advocacy of individual proponents. Accrediting bodies should not only reinforce geriatrics and/or lifespan approaches to health education but also provide specific, testable standards and outcomes and/or evidence of appropriate geriatric coverage and competencies. Without clear standards and required outcomes, programs meet vague goals with varying levels of actual geriatric content. Clearly articulated accreditation requirements, explicit geriatric content licensure, and certification examinations may be the most effective strategy to enhance geriatric expertise and awareness in the health professions (LaMascus et al., 2005). PA programs in the United States, for instance, already require geriatric instruction and supervised clinical experience explicitly focused on older adults for accreditation (Olson et al., 2003). The presence of an advocate for geriatric education appears to be equally important. Programs trying to enhance geriatric coverage should consider hiring individuals with geriatric expertise and passion or existing faculty members could be encouraged to obtain training in gerontology or geriatrics (Kuehn, 2009), particularly if opportunities for such education are available at the same institution.

Participants in our study stressed the importance of an interdisciplinary approach but indicated limited emphasis on interdisciplinary education in their programs (Grumbach & Bodenheimer, 2004). Program directors should consider efforts to enhance interdisciplinary opportunities and build on faculty collaborations so that different health disciplines can share knowledge and resources in providing an integrated array of geriatric educational and training options.

A pervasive theme in our participants’ observations was challenges in providing geriatric education and training that result from limited student exposure to older adults, both in terms of developing intergenerational cultural competence and nurturing student interest. Despite challenges in establishing geriatric clinical experiences for students, such exposure improves attitudes toward older adults and increases interest in geriatrics (Damron-Rodriguez, Kramer, & Gallagher-Thompson, 1998). But students are likely to experience uncertainty and fear interacting with older adults, if this exposure does not have sufficient curricular grounding to develop realistic and informed attitudes toward aging and provide the confidence and support needed to obtain value from, rather than be turned off by, these experiences (Davis, Bond, Howard, & Sarkisian, 2011; Robinson & Cubit, 2005, 2007). Five of the seven programs we studied had creative approaches to increasing student’s geriatric knowledge through elder mentor partnerships or interactive–reflective assignments. Such creative approaches facilitate training providers who are competent at delivering care across the lifespan.

Considered in broader societal context, our study highlights the long-term potential for health training programs to enrich the existing health care system by contributing significantly to reducing gerontological illiteracy and, by extension, reassessing models of late life care (Rowles, 2011). Many programs have sophisticated pediatric components but currently blend consideration of older adults into the adulthood curriculum within a monolithic model of inexorable and undifferentiated late life decline. This reflects and reinforces the existing health care system; there is no effective educational counterpoint to the dominance of a disability and institutionally based model of late life care. Our participants expressed a need for policy change to encourage geriatric specialization and new models of late life health care. Faculty in health professional programs are not only uniquely situated to influence future providers’ knowledge and expertise in geriatrics but also to encourage students to become engaged in policy dialogue to change the existing system and develop models that better serve future generations of older adults.

In a time of fiscal constraint and retrenchment in many academic medical centers, it is easy to revert to the tried and true excuses for lack of emphasis on geriatric education that have existed for decades—a crowded curriculum, lack of interested or trained faculty, limited student interest, low levels of reimbursement, and gerophobia. Although we can conclude that some progress has been made in providing geriatric education within the health professions, we still remain woefully short of accomplishing the imperatives in education and training for which Schneider and Williams, (1986) advocated more than a quarter of a century ago. In a health culture pervaded by an endemic lack of institutional commitment to geriatrics and gerontological education, we wonder how long it will take for an understanding of the particular needs and health-related dilemmas faced by older adults to become a normative and pervasive component of health sciences education. To achieve a future health care workforce attuned to addressing the needs of an older population, it is imperative that we move from grudging, glacierlike acceptance of the need for geriatric and gerontological education toward enthusiastically embracing such education as a societal priority that must be met regardless of cost and profitability. The institutional commitment of academic medical centers will be essential, even if this has to be achieved through the requirements of accreditation bodies. Our hope, however, is that such institutional change can result from the inspired advocacy of geriatricians and gerontologists who are passionate about the need to improve geriatric education. Only by moving in such directions can we avoid another reiteration of Schneider and Williams’ lament in 25 years’ time.

Funding

This publication was supported by grant TL1 RR033172 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), funded by the Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health (NIH) , and supported by the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research.

Acknowledgments

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NCRR and NIH.

References

- Administration on Aging. Older population by age group: 1900 to 2050 with chart of the 65+ population. 2010. Retrieved September 27, 2011, from http://www.aoa.gov/AoARoot/Aging_Statistics/future_growth/future_growth.aspx#age. [Google Scholar]

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing, John A. Hartford Foundation Institute for Geriatric Nursing. Older adults: Recommended baccalaureate competencies and curricular gudielines for geriatric nursing care. 2000. Retrieved from http://www.aacn.nche.edu/education/gercomp.htm. [Google Scholar]

- American Geriatrics Society Geriatrics Workforce Policy Studies Center. Table 1.4: Projection on future number of geriatricians in the United States. 2011. Retrieved September 27, 2011, from http://www.adgapstudy.uc.edu/figs_practice.cfm. [Google Scholar]

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. 2011 Standards and implementation procedures for the certificate of clinical competence in audiology. 2010a. Retrieved from http://www.asha.org/Certification/Aud2011Standards/#Standard%20II. [Google Scholar]

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Speech-language pathology exam content. 2010b. Retrieved from http://www.asha.org/certification/praxis/slp_content.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Proceedings of the Regional Institutes on Geriatrics and Medical Education. Washington, DC: Author; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Association of American Medical Colleges. GQ medical school graduation questionnaire: All schools summary report. 2010. Retrieved from http://www.aamc.org/data/gq/allschoolsreports/gqfinalreport_2009.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett K, McCowan C, Evans JMM, Gillespie ND, Davey PG, Fahey T. Prevalence and outcomes of use of potentially inappropriate medicines in older people: Cohort study stratified by residence in nursing home or in the community. BMJ Quality & Safety. 2011;20:275–281. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs.2009.039818. doi:10.1136/bmjqs.2009.039818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begala JA. Geriatric education in Ohio: A model for change. The Gerontologist. 1980;20:547–551. doi: 10.1093/geront/20.5_part_1.547. doi:10.1093/geront/20.5_Part_1.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman A, Mezey M, Kobayashi M, Fulmer T, Stanley J, Thornlow D, Rosenfeld P. Gerontological nursing content in baccalaureate nursing programs: Comparison of findings from 1997 and 2003. Journal of Professional Nursing. 2005;21:268–275. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2005.07.005. doi:10.1016/j.profnurs.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birenbaum A, Aronson M, Seiffer S. Training medical students to appreciate the special problems of the elderly. The Gerontologist. 1979;19:575–579. doi: 10.1093/geront/19.6.575. doi:10.1093/geront/19.6.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugna RA, Cawley JF, Baker MD. Physician assistants in geriatric medicine. Clinical Geriatrics. 2007;15:22–28. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Health Workforce Studies. The impact of the aging population on the health workforce in the United States: Summary of key findings. 2006. Retrieved from http://www.albany.edu/news/pdf_files/impact_of_aging_excerpt.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherry D, Lucas C, Decker SL. Population aging and the use of office-based physician services. NCHS Data Brief. 2010 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db41.htm. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherubini A, Huber P, Michel J.-P. Geriatric medicine education in Europe. Principles and practice of geriatric medicine. John Wiley: West Sussex, UK; 2006. pp. 1781–1787. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen HJ, Feussner JR, Weinberger M, Carnes M, Hamdy RC, Hsieh F, et al. A controlled trial of inpatient and outpatient geriatric evaluation and management. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;346:905–912. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa010285. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa010285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry RH, Fasser CE, Schafft G. Physician assistant training and practice in geriatric medicine. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education. 1988;7:55–66. doi: 10.1300/J021v07n02_07. doi:10.1300/J021v07n03_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damron-Rodriguez J, Kramer BJ, Gallagher-Thompson D. Effect of geriatric clinical rotations on health professions trainees’ attitudes about older adults. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education. 1998;19:67–79. doi:10.1300/J021v19n02_07. [Google Scholar]

- Davis MM, Bond LA, Howard A, Sarkisian CA. Primary care clinician expectations regarding aging. The Gerontologist. 2011;51:856–866. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr017. doi:10.1093/geront/gnr017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan TA, Lauer DS. Delphi study to identify core competencies in geriatric dentistry. Special Care in Dentistry. 2001;21:191–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.2001.tb00254.x. doi:10.1111/j.1754-4505.2001.tb00254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta AP, Daftary MN, Oke F, Mims B, Hailemeskel B, Sansgiry SS. Geriatric education in U.S. schools of pharmacy: A snapshot. The Consultant Pharmacist. 2005;20:45–52. doi: 10.4140/tcp.n.2005.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eleazer GP, Doshi R, Wieland D, Boland R, Hirth VA. Geriatric content in medical school curricula: Results of a national survey. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2005;53:136–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53023.x. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elster SK. Symposium on the Geriatric Medical Education Imperative: Committee on Medical Education, the New York Academy of Medicine. Bulletin of the New York Academy on Medicine. 1985;61(6):469–470. [Google Scholar]

- Federation of State Boards of Physical Therapy. Physical Therapist National Physical Therapy Examination (NPTE) test content outline. 2007. Retrieved from https://www.fsbpt.org/download/ContentOutline_2008PTT_20100504.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Gazewood JD, Vanderhoff B, Ackermann R, Cefalu C. Geriatrics in family practice residency education: An unmet challenge. Family Medicine. 2003;35:30–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geriatrics Workforce Policy Studies Center. Survey of geriatric academic leaders in U.S. allopathic and osteopathic medical schools. Cincinnati, OH: University of Cincinnati; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Granick R, Simson S, Wilson LB. Survey of curriculum content related to geriatrics in physical therapy education programs. Physical Therapy. 1987;67:234–237. doi: 10.1093/ptj/67.2.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray SL, Elliott D, Semla T. Implications for pharmacy from the Institute of Medicine's report on health care workforce and an aging America. The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 2009;43:1133–1138. doi: 10.1345/aph.1L589. doi:10.1345/aph.1L589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grocki JH, Fox GE., Jr Gerontology coursework in undergraduate nursing programs in the United States: A regional study. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 2004;30:46–51. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-20040301-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grumbach K, Bodenheimer T. Can health care teams improve primary care practice? Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;291:1246–1251. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.10.1246. doi:10.1001/jama.291.10.1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hachmuth FA, Hootman JM. What impact on PA education? A snapshot of ambulatory care visits involving PAs. Journal of the American Academy of Physician Assistants. 2001;14:49–50. 22–24, 27–38; quiz. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Aging and medical education: Report of a study. 1978. (IOM Publication No. 78–04). Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Ironside PM, Tagliareni ME, McLaughlin B, King E, Mengel A. Fostering geriatrics in associate degree nursing education: An assessment of current curricula and clinical experiences. Journal of Nursing Education. 2010;49:246–252. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20100217-01. doi:10.3928/01484834-20100217-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kastenbaum R. The reluctant therapist. Geriatrics. 1963;18:296–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovner CT, Mezey M, Harrington C. Who cares for older adults? Workforce implications of an aging society. Health Affairs. 2002;21:78–89. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.5.78. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.21.5.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuehn BM. Effort under way to prepare physicians to care or growing elderly population. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;302:727–728. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1140. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaMascus AM, Bernard MA, Barry P, Salerno J, Weiss J. Bridging the workforce gap for our aging society: How to increase and improve knowledge and training. Report of an expert panel. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 2005;53:343–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53137.x. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libow LS. A geriatric medical residency program. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1976;85:641–647. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-85-5-641. doi:10.1059/0003-4819-85-5-641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merriam SB. Case study research in education. A qualitative approach. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammad A, Preshaw P, Ettinger R. Current status of predoctoral geriatric education in U.S. dental schools. Journal of Dental Education. 2003;67:509–514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Association of Boards of Pharmacy. NAPLEX blueprint. 2010. Retrieved from http://www.nabp.net/programs/examination/naplex/naplex-blueprint/ [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2009: With special feature on medical technology. 2010. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus09.pdf#092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odegard PS, Breslow RM, Koronkowski MJ, Williams BR, Hudgins GA. Geriatric pharmacy education: A strategic plan for the future. American Journal of Pharmacy Education. 2007;71:47. doi: 10.5688/aj710347. doi:10.5688/aj710347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okwuje I, Anderson E, Valachovic RW. Annual ADEA survey of dental school seniors: 2008 graduating class. Journal of Dental Education. 2009;73:1009–1032. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson TH, Stoehr J, Shukla A, Moreau T. A needs assessment of geriatric curriculum in physician assistant education. Perspective on Physician Assistant Education. 2003;14:208–213. [Google Scholar]

- Panneton PE, Wesolowski EF. Current and future needs in geriatric education. Public Health Reports. 1979;94:73–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfizer. Pfizer facts: The health status of older adults. 2007. Retrieved from http://media.pfizer.com/files/products/The_Health_Status_of_Older_Adults_2007.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Phelan EA, Genshaft S, Williams B, LoGerfo JP, Wagner EH. A comparison of how generalists and fellowship-trained geriatricians provide “geriatric” care. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2008;56:1807–1811. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01942.x. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01942.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips RM. The challenge of medication management in older adults. Nursing Made Incredibly Easy! 2011;9:24–31. doi:10.1097/01.NME.0000390925.84948.ad. [Google Scholar]

- Physician Assistant. Merriam-Webster's medical dictionary. Merriam-Webster; 2011. Incorporated. Retrieved October 25, 2011, from http://www2.merriam-webster.com/cgi-bin/mwmedsamp. [Google Scholar]

- Portal of Geriatric Online Education. AAMC geriatric competencies for medical students. 2010. Retrieved from http://www.pogoe.org/Minimum_Geriatric_Competencies. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt C, Simonson W, Boehne R. Geriatric pharmacy curriculum in U.S. pharmacy schools, 1985–86. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education. 1987;7:17–27. doi: 10.1300/j021v07n03_03. doi:10.1300/J021v07n03_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt C, Simonson W, Lloyd S. Pharmacists’ perceptions of major difficulties in geriatric pharmacy practice. The Gerontologist. 1982;22:288–292. doi: 10.1093/geront/22.3.288. doi:10.1093/geront/22.3.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preshaw PM, Mohammad AR. Geriatric dentistry education in European dental schools. European Journal of Dental Education. 2005;9:73–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0579.2004.00357.x. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0579.2004.00357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulcini J, Jelic M, Gul R, Loke AY. An international survey on advanced practice nursing education, practice, and regulation. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2010;42:31–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2009.01322.x. doi:10.1111/j.1547-5069.2009.01322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson A, Cubit K. Student nurses’ experiences of the body in aged care. Contemporary Nurse. 2005;19:41–51. doi: 10.5172/conu.19.1-2.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson A, Cubit K. Caring for older people with dementia in residential care: Nursing students’ experiences. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2007;59:255–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.4304.x. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.4304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowles GD. Living an old age imagined. Speech presented at the 37th annual meeting of the Association for Gerontology in Higher Education, Cincinnati, OH. 2011, March. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin CD, Stieglitz H, Vicioso B, Kirk L. Development of geriatrics-oriented faculty in general internal medicine. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2003;139:615–620. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-7-200310070-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders R, Yellowitz J, Dolan T, Smith B. Trends in predoctoral education in geriatric dentistry. Journal of Dental Education. 1998;62:314–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherer YK, Bruce SA, Montgomery CA, Ball LS. A challenge in academia: Meeting the healthcare needs of the growing number of older adults. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners. 2008;20:471–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00350.x. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider EL, Williams TF. Geriatrics and gerontology: Imperatives in education and training. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1986;104(3):432–435. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-104-3-432. doi:10.1059/0003-4819-104-3-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Warshaw GA, Bragg EJ, Shaull RW, Lindsell CJ. Academic geriatric programs in US allopathic and osteopathic medical schools. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288:2313–2319. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.18.2313. doi:joc20696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendt A. Mapping geriatric nursing competencies to the 2001 NCLEX-RN test plan. Nursing Outlook. 2003;51:152–157. doi: 10.1016/s0029-6554(03)00119-2. doi:10.1016/S0029-6554(03)00119-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]