Abstract

The economic impact of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) remains unclear. We developed an economic simulation model to quantify the costs associated with CA-MRSA infection from the societal and third-party payer perspectives. A single CA-MRSA case costs third-party payers $2,277 – $3,200 and society $7,070 – $20,489, depending on patient age. In the United States (US), CA-MRSA imposes an annual burden of $478 million - 2.2 billion on third-party payers and $1.4 billion - 13.8 billion on society, depending on the CA-MRSA definitions and incidences. The US jail system and Army may be experiencing annual total costs of $7 – 11 million ($6 – 10 million direct medical costs) and $15 – 36 million ($14 – 32 million), respectively. Hospitalization rates and mortality are important cost drivers. CA-MRSA confers a substantial economic burden to third-party payers and society, with CA-MRSA-attributable productivity losses being major contributors to the total societal economic burden. Although decreasing transmission and infection incidence would decrease costs, even if transmission were to continue at present levels, early identification and appropriate treatment of CA-MRSA infections before they progress could save considerable costs.

Keywords: Community, MRSA, Economics, Cost, CA-MRSA

INTRODUCTION

Studies have suggested that community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA, i.e., MRSA colonization and infection not associated with healthcare settings) is a substantial public health problem[1–2]. CA-MRSA strains are common causes of skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs) in the United States (US)[3–4] with reported outbreaks in many diverse settings and populations including prisoners, military recruits, and athletes[5–6]. CA-MRSA strains have become endemic[7–8]; predominantly causing SSTIs but also necrotizing pneumonia and invasive syndromes such as necrotizing fasciitis, osteomyelitis, septic thrombophlebitis, bacteremia, and severe sepsis[6]. While studies have shown increases in CA-MRSA infection incidence among veterans[9] and CA-MRSA SSTI incidence[10], its overall incidence in the US has not been clearly delineated. Although the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has initiated CA-MRSA public awareness campaigns,[11] there is a dearth of documented community-level efforts to curb transmission.

An extensive literature search for economic studies on CA-MRSA yielded only two: one quantifying the cost impact of an epidemic on Driscoll Children’s health plan[12] and another focusing on just pneumonia patients.[13] Until CA-MRSA’s overall economic burden is better quantified, it may be difficult for decision makers to determine where CA-MRSA should fall on public health, medical, and scientific priority lists. Without an estimate of the costs associated with CA-MRSA infections, many questions remain. For example, how much should policy makers invest in prevention, education, and control? Should insurance companies focus efforts and reimbursement policies for prevention and control? How much should be invested in developing new diagnostic, prevention, and treatment interventions? Therefore, we developed an economic computational model to quantify the costs associated with CA-MRSA infection from third-party payer and societal perspectives.

METHODS

Model Structure

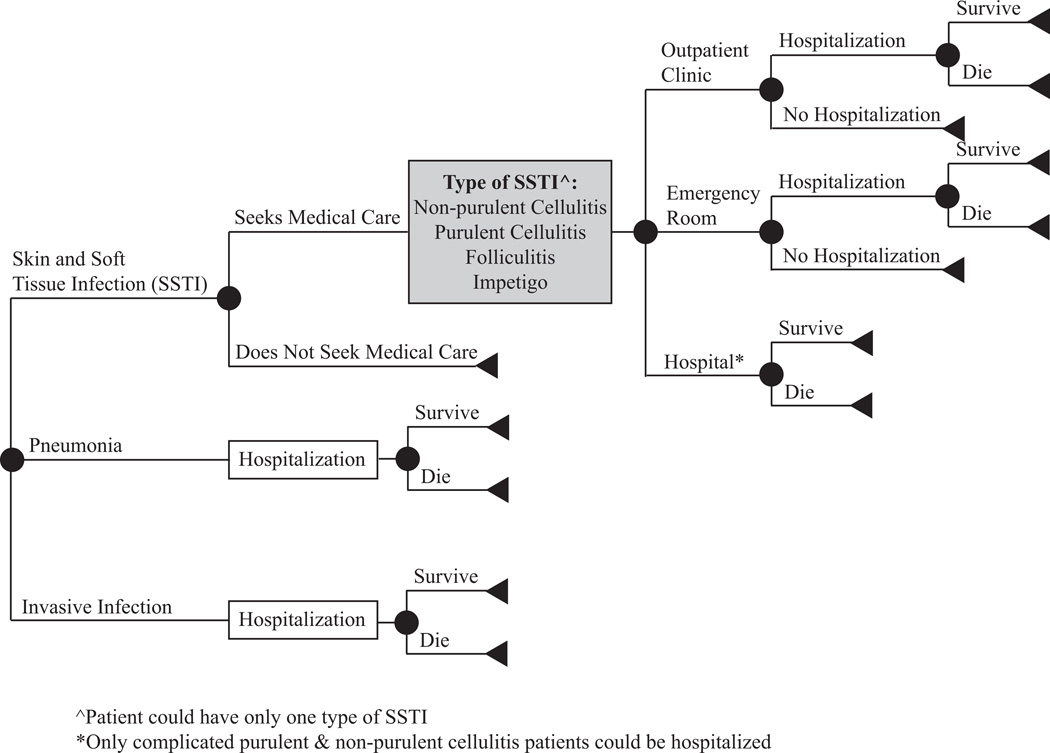

Figure 1 outlines the structure of our economic simulation model developed in TreeAge Pro 2009 (Williamstown, MA) to determine the costs associated with a CA-MRSA infection from third-party payer and societal perspectives. Table 1 displays the model inputs. To obtain these values, we conducted an extensive Medline search using key words ("Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus", "Staphylococcus aureus", "Methicillin Resistance", "Community-Acquired Infections", and “CA-MRSA”) to identify studies and excluded those conducted outside the US or among immuno-compromised populations. Our study used the CDC epidemiologic definition of CA-MRSA to determine each infection type probability. An infection was considered CA-MRSA if the culture was obtained during an outpatient visit or within 48 hours of hospital admission. Also within the past year, the patient must have not been admitted to a hospital, nursing home, or any other long-term care facility and did not have hemodialysis or surgery. Furthermore an indwelling catheter or a percutaneous device must not have been in place at the time of culture[6].

Figure 1.

General structure of the decision model

Table 1.

Model Input Parameters.

| Parameter | Distribution Type* |

Mean/Median | Standard Deviation (SD) or Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skin and Soft Tissue Infection (SSTI; includes: non-purulent cellulitis, impetigo, folliculitis, uncomplicated purulent cellulitis, or complicated SSTI) | |||

| Probabilities | |||

| Having an SSTI | β | 0.78 | 0.0004 |

| Incision & drainage in ambulatory settings for purulent cellulitis (adult) | 0.83 | ||

| Incision & drainage in ambulatory settings for purulent and non-purulent cellulitis (pediatric) | 0.144 | ||

| Incision & drainage in hospital with purulent cellulitis (adult) | 0.98 | ||

| Incision & drainage in hospital for purulent and non-purulent cellulitis (pediatric) | 0.478 | ||

| Healthcare utilization if seek medical care: | |||

| Outpatient facility visit | 0.738 | ||

| Emergency room (ER) visit | 0.205 | ||

| Hospitalization after outpatient visit | 0.021 | ||

| Hospitalization after ER -visit | Δ | 0.136 | 0.105 – 0.147 |

| Hospital (adult) | 0.057 | ||

| Hospital (pediatric) | 0.25 | ||

| In hospital mortality (adult) | 0.001 | ||

| In hospital mortality (pediatric) | 0 | ||

| Costs (US$) | |||

| Hospitalization^ (<1 year old) | γ | 3891.2 | 137.68 |

| Hospitalization^ (1–17 years old) | γ | 3891.2 | 120.2 |

| Hospitalization^ (18–44 years old) | γ | 5,842.57 | 88.76 |

| Hospitalization^ (45–64 years old) | γ | 7,252.78 | 113.89 |

| Hospitalization^ (65–84 years old) | γ | 7,708.01 | 140.02 |

| Hospitalization^ (85 years old and over) | γ | 7,053.17 | 138.29 |

| Incision and drainage in ER^ | γ | 389.67 | 228.62 |

| Incision and drainage in outpatient settings^ | γ | 396.07 | 159.88 |

| Debridement cost in facility^ | γ | 436.14 | 333.29 |

| Neosporin | γ | 6.01 | 1.84 |

| 2% Mupirocin | γ | 56.86 | 19.61 |

| Durations | |||

| Outpatient/ER visit (hours) | 4 | ||

| Hospitalization (median, days) | Δ | 4 | 3 – 5 |

| Outpatient length of therapy (days) | U | 5 – 10 | |

| Inpatient length of therapy (days) | U | 7 – 14 | |

| Pneumonia | |||

| Probabilities | |||

| Having pneumonia | β | 0.053 | 0.00046 |

| Hospitalization | 1.0** | ||

| In hospital mortality (adult) | β | 0.12 | 0.088 – 0.15 |

| In hospital mortality (pediatric) | 0.076 | ||

| Costs (US$) | |||

| Hospitalization^ (<1 year old) | γ | 39112.2 | 6234.91 |

| Hospitalization^ (1–17 years old) | γ | 22673.63 | 5141.96 |

| Hospitalization^ (18–44 years old) | γ | 24,384.77 | 3621.71 |

| Hospitalization^ (45–64 years old) | γ | 26,327.53 | 1896.42 |

| Hospitalization^ (65–84 years old) | γ | 20,938.53 | 864.29 |

| Hospitalization^ (85 years old and over) | γ | 17,284.14 | 901.43 |

| Durations | |||

| Hospitalization (adult; days) | γ | 18.2 | 16.6 |

| Hospitalization (pediatric; median, days) | 23.7 | 6 – 138 | |

| Length of therapy (weeks) | U | 1 – 3 | |

| Other Invasive Infections | |||

| Probabilities | |||

| Having an invasive infection | 0.0625 | ||

| Hospitalization | 1.0** | ||

| Echocardiogram (pediatric) | 0.10 – 0.20 | ||

| In hospital mortality (adult) | β | 0.1583 | 0.000231 |

| In hospital mortality (pediatric) | β | .0246 | .0240 |

| Costs (US$) | |||

| Hospitalization^ (<1 year old) | γ | 6581.56 | 810.71 |

| Hospitalization^ (1–17 years old) | γ | 9377.01 | 890.03 |

| Hospitalization^ (18–44 years old) | γ | 13,560.29 | 921.74 |

| Hospitalization^ (45–64 years old) | γ | 14,390.99 | 787.05 |

| Hospitalization^ (65–84 years old) | γ | 13,691.28 | 550.31 |

| Hospitalization^ (85 years old and over) | γ | 10,883.61 | 349.61 |

| Durations | |||

| Hospitalization (adult; days) | Δ | 6.0 | 4 – 8.5 |

| Hospitalization (pediatric; days) | 14.2 | 7.6 | |

| Length of therapy (weeks) | U | 2 – 3 | |

| General Parameters | |||

| Costs (US$) | |||

| IV insertion^ | 25.14 | ||

| Echocardiogram^ | γ | 334.31 | 31.22 |

| Oral TMP-SMX† daily dose | γ | 3.53 | 0.82 |

| Vancomycin IV daily dose/kg (adult) | γ | 0.42 | 0.32 |

| Vancomycin IV daily dose/kg (pediatric) | γ | 0.84 | 0.65 |

| Home healthcare visit | 124.63 | ||

| Hourly wage (median) | 16.92 | ||

| Mortality (median) | Δ | 7,128.81 | 5,346.61 – 9,295.96 |

| Productivity loss due to mortality | |||

| <1 year | 1,080,911 | ||

| 1 year | 1,077,435 | ||

| 5 years | 1,062,460 | ||

| 10 years | 1,041,071 | ||

| 15 years | 1,016,275 | ||

| 20 years | 958,767 | ||

| 35 years | 880,284 | ||

| 50 years | 710,688 | ||

| 65 years | 514,261 | ||

| 85 years | 252,025 | ||

| Sensitivity Analysis | |||

| Parameter | Baseline | Range of Sensitivity Analysis | |

| SSTI patients seeking care | 0.30 | 0.10 – 0.40 | |

| Incision & drainage in ambulatory settings for purulent cellulites (adult) | 0.83 | 0.65 – 0.85 | |

| SSTI hospitalization (adult) | 0.057 | 0.05 – 0.45 | |

| SSTI hospitalization (pediatric) | 0.25 | 0.05 – 0.45 | |

NOTE: References for parameters are listed in Appendix 1.

β: beta distribution; γ: Gamma distribution; Δ: Triangular distribution; U: Uniform distribution

Oral TMP-SMX dosage: two double strength trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) tablets twice daily for adults and 8–12 mg/kg of trimethoprim per day for children (individuals <18 years age)

Estimates from online database (as detailed in Appendix 1)

Since, Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) treatment guidelines recommend vancomycin IV treatment for MRSA pneumonia and invasive patients, they all would require hospitalization.

Every individual entering the model had a CA-MRSA infection, having one of three major clinical categories (approximately 90% of all types): SSTI (non-purulent cellulitis, impetigo, folliculitis, uncomplicated purulent cellulitis, or complicated SSTI), pneumonia, or other invasive infection (infection of a normally sterile body site, mostly bacteremia). Some SSTIs sought medical care and those who did not relied on self-medication with over-the-counter Neosporin™ (neomycin, polymyxin B sulfate and bacitracin) ointment. SSTIs patients who sought care were treated in an outpatient clinic, emergency room (ER), or hospital. All patients with pneumonia or other invasive infection required hospitalization. When probabilities did not sum to one, a Dirchilet distribution was used to normalize the probabilities.

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines and expert opinion guided the treatment regimen for each syndrome[14]:

Non-purulent cellulitis (outpatient): 5–10 day course of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX)

Impetigo (outpatient): 2% topical mupirocin ointment twice a day for approximately 2 weeks

Folliculitis (outpatient): warm-water packs/presses (no cost)

Uncomplicated purulent cellulitis (outpatient): incision and drainage (I&D) with or without TMP-SMX

Complicated SSTI (hospitalized): intravenous (IV) vancomycin (dosed by age and weight), switched to a 5–10 day course of TMP-SMX one day prior to discharge; almost all required I&D

Pneumonia: IV vancomycin during hospitalization, switched to TMP-SMX one day prior to discharge for a total therapy duration of 1–3 weeks

Other invasive infections: IV vancomycin during hospitalization with 2–3 weeks subsequent home health nursing with IV vancomycin administration; pediatric patients could receive an echocardiogram

Selected regimens were conservative (least expensive) and do not represent all possible regimens recommended by IDSA Guidelines or used in practice.

The third-party payer perspective included only direct medical costs (i.e., outpatient/ER visit, hospitalization, and treatment costs), while the societal perspective included both direct and indirect (i.e., productivity losses due to work absenteeism from healthcare visits and hospitalization for individuals or caregivers if patient ≤18 years, and mortality) costs. Median hourly and annual wages for all occupations served as proxies for productivity losses. Work absenteeism was calculated for 4 hours missed for an outpatient visit and 8 hours per day for the duration of hospitalization (Table 1). Death resulted in the net present value of lost wages for the remainder of the person's life expectancy based on his/her age[15]. A 3% discount rate adjusted all costs to 2011 US$.

Each simulation fixed a patient’s age sending 1,000 patients with CA-MRSA infections through the model 1,000 times (1,000,000 total trials). Subsequent simulations systematically varied patient age (range: <1 to 85 years).

Study Populations

Simulations determined the cost of a single CA-MRSA infection and an SSTI infection for different patient ages. Multiplying by the number of cases nationally, these costs-per-case were extrapolated to the annual national burden. Annual US cases estimates came from three studies. Study 1 estimated 94,360 invasive MRSA cases, categorizing 13.7% as community-associated using CDC criteria[16]. Assuming 6.25% of all CA-MRSA infections are invasive[17], there would be 206,837 CA-MRSA infections per year. Study 2 reported an annual incidence of community-onset MRSA infections (i.e., occurring among persons not hospitalized in the prior year) of 243 per 100,000[18]. Extending nationwide resulted in 720,277 CA-MRSA cases per year. Study 3 reported an incidence of 521 CA-MRSA SSTIs per 100,000 in Chicago (presented at IDSA 2011 annual meeting)[19], which would translate to an estimated 667.9 per 100,000 for all CA-MRSA infections, resulting in 1,979,869 cases, of which 1,544,298 would be SSTIs. The number of pediatric cases among the estimates was determined using data reporting 36.4%[20] and 10.1%[21] of CA-MRSA cases as <18 years old. These estimates were used to determine a range of costs. Study 1 represents the lower estimate, as they used the CDC definition, and Study 3 represents the upper estimate, as they used a 48-hour criterion to define CA-MRSA cases. As SSTIs represent approximately 75%[22] of infections, we determined its burden separately using estimates from Study 3 and Study 4, which reported 164.2 per 100,000 CA-MRSA SSTIs[10].

A similar approach estimated the annual burden for two particularly high-risk sub-populations: jail (prevalence: 4.5 – 79.7%[23]) and military populations (prevalence: ≤5%[24]). David et al. evaluated SSTI incidence and etiology among detainees at Cook County Jail; reporting 15.84 MRSA SSTIs per 1,000 detainee-years (mean age: 33 years) with a census of 10,000 detainees at a given time[25]. An army installation study estimated 35 CA-MRSA SSTI cases per 1,000 soldiers (mean age: 22 years)[24]. These incidence estimates multiplied with cost-per-SSTI-case determined the annual economic burden in these sub-populations.

Sensitivity Analyses

One-way sensitivity analyses systematically varied key parameters one at a time throughout their ranges (Table 1). Monte Carlo probabilistic sensitivity analysis simultaneously varied all parameters throughout their ranges.

RESULTS

Cost to Third-party Payers

Table 2 shows the median and 95% range of the total direct medical costs of a CA-MRSA case from our simulations. Varying the SSTI care-seeking probability (10% – 40%) altered this cost in most cases by <$300 (e.g., median $2,698 with a 10% care-seeking probability and $2,938 with a 40% probability for a 20-year-old). With relatively modest outpatient costs-per-case (median <$100), hospitalization was the primary cost-driver.

Table 2.

Median costs (95% Range*) in $US associated with a CA-MRSA case from the societal and third-party payer perspectives.

| Age | Outpatient Healthcare Costs |

Inpatient Healthcare Costs |

Total Third- Party Payer Costs (Total Direct)◊ |

Mortality Costs† |

Indirect Costs (Total Productivity Losses)†† |

Total Societal Costs (Total Direct and Indirect)◊ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <1 | 27 (24 – 32) |

3,123 (2,547 – 3,713) |

3,200 (2,602 – 3,862) |

6,519 (2,172 – 13,038) |

6,923 (2,570 – 12,345) |

10,212 (5,463 – 15,979) |

| 1 | 29 (25 – 37) |

2,352 (1,943 – 2,761) |

2,373 (2,003 – 2,759) |

6,509 (2,168 – 13,011) |

6,902 (2,565 – 12,382) |

9,361 (4,848 – 15,896) |

| 5 | 33 (26 – 46) |

2,410 (2,004 – 2,812) |

2,435 (2,060 – 2,850) |

6,419 (2,138 – 11,769) |

6,806 (2,535 – 12,145) |

9,291 (4,741 – 15,814) |

| 10 | 39 (29 – 59) |

2,469 (2,099 – 2,918) |

2,517 (2,138 – 2,949) |

6,290 (2,096 – 11,535) |

6,679 (2,479 – 11,972) |

9,270 (4,887 – 15,487) |

| 15 | 74 (64 – 83) |

2,594 (2,168 – 3,062) |

2,635 (2,210 – 3,075) |

6,141 (2,046 – 11,260) |

6,535 (2,449 – 11,649) |

9,183 (4,908 – 14,732) |

| 20 | 73 (65 – 84) |

2,787 (2,371 – 3,236) |

2,849 (2,458 – 3,328) |

17,387 (9,660 – 26,085) |

17,418 (10,677 – 26,067) |

20,489 (13,031 – 28,745) |

| 35 | 74 (64 – 84) |

2,770 (2,363 – 3,218) |

2,861 (2,409 – 3,304) |

15,976 (9,762 – 23,958) |

16,013 (9,840 – 23,925) |

19,166 (11,938 – 27,381) |

| 50 | 74 (64 – 84) |

2,985 (2,539 – 3,416) |

3,068 (2,602 – 3,551) |

12,921 (7,180 – 19,387) |

12,961 (7,284 – 18,695) |

16,048 (10,730 – 22,066) |

| 65 | 74 (64 – 84) |

2,625 (2,227 – 3,032) |

2,711 (2,321 – 3,115) |

9,388 (5,216 – 14,079) |

9,414 (5,298 – 14,088) |

12,200 (8,045 – 16,605) |

| 85 | 74 (63 – 83) |

2,183 (1,882 – 2,518) |

2,277 (1,946 – 2,588) |

4,666 (2,593 – 6,750) |

4,704 (2,908 – 6,983) |

7,070 (4,865 – 9,665) |

95% Range (since this is a stochastic simulation model in which each input parameter draws from a distribution, each output/result has a distribution)

Total third-party payer costs include outpatient/ER visit, hospitalization, and treatment costs; Total societal costs include both direct and indirect (i.e., productivity losses due to work absenteeism from healthcare visits and hospitalization for individuals or caregivers if patient ≤18 years, and mortality) costs

Mortality costs include the productivity losses due to mortality and general mortality costs

Total productivity losses include productivity losses due to absenteeism and mortality

Cost to Society

As Table 2 shows, societal costs were four-to-seven times higher than third-party costs, as the vast majority came from productivity losses, i.e., individuals or caregivers missing work plus lost productivity from infection-related deaths. Again, medical care-seeking probability did not have a substantial impact (increasing by ≤$500). A given child not surviving has higher productivity losses than an adult; however we observe greater productivity losses for adults due to higher mortality rates.

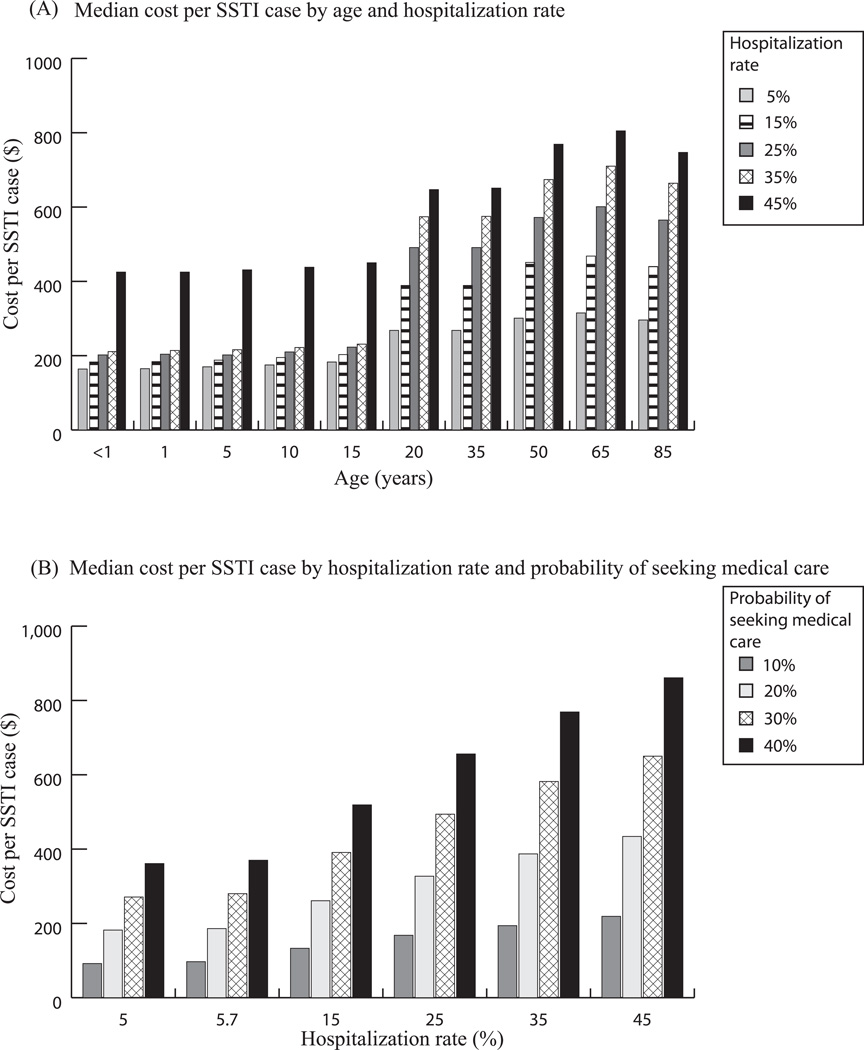

Costs of a CA-MRSA SSTI

At baseline hospitalization values (5.7% for ≥18 years, 25% for <18 years), SSTI costs ranged from $202 (<1 year old) to $326 (65 years) for society and $168 (<1 year old) to $292 (65 years) for third-party payers. Figure 2A shows how SSTI costs (societal perspective) trend with age and hospitalization rate. Approximately 85% – 90% of SSTI costs are direct medical costs. SSTI costs vary by age, largely attributable to adults’ higher mortality. Hospitalization rate was a much stronger cost-driver among adults than children (e.g., increasing from 5% to 45% only increased societal costs by $261 for a one-year-old, but increased costs by $490 for a 65-year-old).

Figure 2.

A) Median cost from a societal perspective by age and hospitalization rate assuming only 30% of SSTI patients seek medical care; B) Median cost per SSTI infection (23 years old) by hospitalization rate and probability of patients seeking care (10%, 20%, 30% and 40%)

Figure 2B shows the SSTI cost trend with hospitalization rate and care-seeking probability for a 23-year-old. The median cost-per-case when 40% of patients seek care ($370) was almost four times higher than when 10% sought care ($97). The cost more than doubled when hospitalization increased from 5% to 45%.

Annual Burden

Table 3 shows the estimated annual total US and sub-population burdens for all CA-MRSA infections and SSTIs. CA-MRSA yielded average annual US costs ≥$560 million to third-party payers. High productivity losses meant societal costs substantially exceeded third-party costs (≥$2.7 billion).

Table 3.

Annual costs (in $US millions) associated with CA-MRSA infections and SSTIs only in the US and in the military and jail system sub-populations

| Incidence Estimate | Third-Party Payer Perspective |

Societal Perspective |

|---|---|---|

| All CA-MRSA Infections Annual US Burden | ||

| Study 1 | ||

| 36.4% of Cases are Pediatric | 560 (478 – 644) | 2,685 (1,621 – 3,464) |

| 10.1% of Cases are Pediatric | 562 (469 – 632) | 2,961 (1,494 – 3,989) |

| Study 2 | ||

| 36.4% of Cases are Pediatric | 1,951 (1,665 – 2,244) | 9,350 (5,646 – 12,063) |

| 10.1% of Cases are Pediatric | 1,958 (1,630 – 2,187) | 10,311 (5,205 – 13,892) |

| Study 3 | ||

| 36.4% of Cases are Pediatric | 5,363 (4,577 – 6,169) | 25,701 (15,520 – 33,159) |

| 10.1% of Cases are Pediatric | 5,509 (5,159 – 6,011) | 28,343 (14,308 – 38,186) |

| SSTI Annual US Burden^ | ||

| Study 3 | ||

| 521 per 100,000* | 343 (259 – 451) | 393 (312 –503) |

| Study 4 | ||

| 164.2 per 100,000* | 108 (82 – 142) | 124 (98 – 159) |

| Military | ||

| 15 per 1,000* | 14 | 16 |

| 25 per 1,000* | 23 | 26 |

| 35 per 1,000[24] | 32 | 36 |

| Jail System | ||

| 10 per 1,000* | 6 | 7 |

| 12 per 1,000* | 7 | 8 |

| 15.84 per 1000[25] | 10 | 11 |

Estimated Incidence

83% require I&D

The estimated annual societal cost to Cook County Jail was $140,265 (65% of outpatient purulent cellulitis cases required I&D) and $146,525 when 85% required I&D; annual direct medical costs ranged from $124,338 to $130,659 (results not shown). Table 3 provides cost estimates for various CA-MRSA incidence rates in jails around the country (748,728 inmates in 2009–2010[26]).

Estimated annual societal costs to an army installation [24] ranged from $834,848 (65% of outpatient purulent cellulitis cases required I&D) to $874,797 (85% required I&D), with annual direct medical costs ranging from $737,618 to $780,354 (results not shown). Table 3 shows the annual costs for all US Army installations.

DISCUSSION

Our study suggests that CA-MRSA confers a substantial economic burden, greater than many other acute infectious diseases that have garnered the attention of policy makers, scientists, and manufacturers. For example, the cost per CA-MRSA infection ($7,070 – $20,489) is two-to-five times that of an influenza case ($3,000 – $4,000[27]), three-to-ten times that of foodborne illness (approximately $1,851[28]) or pertussis ($1,952 per case[29]), and over 17 times that of Lyme Disease ($397 – $923[30]). Moreover, since the incidence of some of these diseases is relatively low (e.g., pertussis and Lyme disease), the annual economic burden of CA-MRSA infections is much higher in comparison, approximately 2 to 13 times higher than pertussis’ (among adults and adolescents) and 8 to 17 times higher than Lyme disease’s. These numbers help justify investment in effective CA-MRSA prevention and control and imply that even minimal investment could generate favorable returns for policy makers, military, and US jail systems. Our results can also help guide funders and manufacturers in establishing priorities.

Our results show that CA-MRSA may have hidden costs that may be missed by certain estimation methods. Since direct medical costs are only a minority (approximately 25%) of the total cost for all CA-MRSA infections, many hospital and insurance databases may not capture productivity losses, thus, greatly underestimating costs. Additionally, a substantial proportion of costs come from the small fraction of deaths. Therefore, focusing on the majority of cases that carry relatively low costs (e.g., over-the-counter medications, clinic visit, course of antibiotics, and perhaps a half-day of lost productivity) overlooks the impact of complicated cases that rapidly accrue costs. Appropriate measures could prevent the bulk of CA-MRSA-associated costs. Reducing transmission and infection incidence would decrease costs. Even if infection incidence were to remain at present levels, early identification and proper treatment of infections before they progress could spare considerable costs.

Therefore, research and policy development could best proceed concurrently in two directions: (1) developing and implementing measures to reduce transmission and (2) identifying and treating uncomplicated infections early to ensure they do not become invasive. These require a better understanding of CA-MRSA transmission dynamics and involve determining who may be at increased risk for disease progression and more complicated infections. Studies have suggested that crowded environments, lack of hygienic conditions, sharing contaminated objects (e.g., towels), and compromised skin integrity lead to increased transmission[31]. Additionally, individuals with compromised immune systems, prior antibiotic use, or other co-morbidities may be at higher risk[6, 32]. However, much remains unknown. Additionally, considerable variability remains in antimicrobial management[14, 33]; evolving resistance patterns may further alter the therapeutic landscape. Considerable debate remains over the definitions and incidence of CA-MRSA infections. CA-MRSA infection criteria have varied in the literature, from narrower epidemiological criteria of the CDC definition to broader criteria, such as the 48-hour criterion, which classifies CA-MRSA infections diagnosed among inpatients cultured within 48 hours of admission to a hospital and all outpatients, with the broader definition leading to a higher estimated incidence[20]. Since our study demonstrates that annual US burden is rather sensitive to such definitions, future studies should clearly state the definition criteria used. Despite the variability in costs, our study offers the general magnitude of the problem, i.e., it at least cost several billion dollars, perhaps much more, to society and at least half a billion to third-party payers. Getting a consensus definition of CA-MRSA and obtaining better infection incidence data would further hone this cost estimate.

Limitations

All models, by definition, are simplifications of real life and cannot include every possible CA-MRSA infection outcome[34]. Our model’s parameter values came from studies with varying rigor and study populations (which may not be comparable) and may change as new studies emerge. For simplicity, we divided infections into discrete syndromic categories, while infections may involve multiple categories or other severe manifestations.

Endeavoring to be conservative (e.g., using the least expensive treatment options and the CDC definition) likely underestimates CA-MRSA’s economic burden. Also, our productivity loss calculations assumed a 40 hour work week, missed work only during outpatient visits or hospitalization, and did not experience decreased productivity while recovering. Our model did not account for all possible procedures (e.g., pleural drainage and video assisted thoracoscopic surgery) and permanent disability (e.g., amputation) that may result from severe infections. Our model did not include infection control interventions for CA-MRSA carriers or in-hospital transmission, or their associated costs.

Conclusions

The considerable economic burden of CA-MRSA infections may justify further investment in prevention and control. Much of the overall burden stems from productivity losses. A substantial proportion comes from a minority of cases resulting in death. Although decreasing transmission and infection incidence would decrease costs, early identification and appropriate treatment of infections before they progress could save considerable costs. Therefore, research and policy development may involve developing and implementing measures to reduce transmission, identify infections early, and prevent minor infections from progressing. Although decision makers may have been aware of some of these issues, quantifying their general magnitude could help motivate, plan for, and guide investment in relevant interventions and overcome the current general dearth of community-level interventions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

This study was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences Models of Infectious Disease Agent Study (MIDAS) grants 5U54GM088491-02 and 5U01GM087729-03 and by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grant 1RC4AI092327-01. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

We are not aware of any significant conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Herold BC, Immergluck LC, Maranan MC, Lauderdale DS, Gaskin RE, Boyle-Vavra S, et al. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in children with no identified predisposing risk. JAMA. 1998 Feb 25;279(8):593–598. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.8.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Otto M. Community-associated MRSA: a dangerous epidemic. Future Medicine Ltd. 2007;2(5):457–479. doi: 10.2217/17460913.2.5.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moran GJ, Krishnadasan A, Gorwitz RJ, Fosheim GE, McDougal LK, Carey RB, et al. Methicillin-resistant S. aureus infections among patients in the emergency department. N Engl J Med. 2006 Aug 17;355(7):666–674. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walraven CJ, Lingenfelter E, Rollo J, Madsen T, Alexander DP. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Evaluation of Community-acquired Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA) Skin and Soft Tissue Infections in the Emergency Department. J Emerg Med. 2011 Apr 25; doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kluytmans-Vandenbergh MF, Kluytmans JA. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: current perspectives. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2006 Mar;12(Suppl 1):9–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2006.01341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.David MZ, Daum RS. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: epidemiology and clinical consequences of an emerging epidemic. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2010;23(3):616–687. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00081-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maree CL, Daum RS, Boyle-Vavra S, Matayoshi K, Miller LG. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates causing healthcare-associated infections. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007 Feb;13(2):236–242. doi: 10.3201/eid1302.060781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.King MD, Humphrey BJ, Wang YF, Kourbatova EV, Ray SM, Blumberg HM. Emergence of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus USA 300 clone as the predominant cause of skin and soft-tissue infections. Ann Intern Med. 2006 Mar 7;144(5):309–317. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-5-200603070-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tracy LA, Furuno JP, Harris AD, Singer M, Langenberg P, Roghmann MC. Staphylococcus aureus infections in US veterans, Maryland, USA, 1999–2008. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011 Mar;17(3):441–448. doi: 10.3201/eid1703.100502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hota B, Ellenbogen C, Hayden MK, Aroutcheva A, Rice TW, Weinstein RA. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin and soft tissue infections at a public hospital: do public housing and incarceration amplify transmission? Arch Intern Med. 2007 May 28;16710:1026–1033. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.10.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Center of Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention of MRSA Infections. Atlanta: 2010. [cited 2012]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/mrsa/prevent/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Purcell K, Fergie J, Peterson MD. Economic impact of the community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus epidemic on the Driscoll Children's Health Plan. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006 Feb;25(2):178–180. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000199304.68890.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taneja C, Haque N, Oster G, Shorr AF, Zilber S, Kyan PO, et al. Clinical and economic outcomes in patients with community-acquired Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia. J Hosp Med. 2010 Nov-Dec;5(9):528–534. doi: 10.1002/jhm.704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, Daum RS, Fridkin SK, Gorwitz RJ, et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the infectious diseases society of america for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children. Clin Infect Dis. 2011 Feb;52(3):e18–e55. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Human Mortality Database [database on the Internet] University of California, Berkeley (USA), and Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (Germany) 2008 Available from: www.mortality.org.

- 16.Klevens RM, Morrison MA, Nadle J, Petit S, Gershman K, Ray S, et al. Invasive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in the United States. JAMA. 2007 Oct 17;298(15):1763–1771. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.15.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fridkin SK, Hageman JC, Morrison M, Sanza LT, Como-Sabetti K, Jernigan JA, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus disease in three communities. N Engl J Med. 2005 Apr 7;352(14):1436–1444. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu C, Graber CJ, Karr M, Diep BA, Basuino L, Schwartz BS, et al. A population-based study of the incidence and molecular epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus disease in San Francisco, 2004–2005. Clin Infect Dis. 2008 Jun 1;46(11):1637–1646. doi: 10.1086/587893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Popovich KJ, David MZ, Grasso AE, Daum RS, Hota B, Lauderdale DS, editors. Abstract #842 Community-Associated Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) Skin and Soft Tissue Infections (SSTI) in Chicago, 2005–8: High-Risk Clusters and Trends in Incidence 49th Annual Meeting Infectious Disease Society of America. Boston, MA: 2011. Oct 22, [Google Scholar]

- 20.David MZ, Glikman D, Crawford SE, Peng J, King KJ, Hostetler MA, et al. What is community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus? J Infect Dis. 2008 May 1;197(9):1235–1243. doi: 10.1086/533502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller LG, Remington FP, Bayer AS, Diep B, Tan N, Bharadwa K, et al. Clinical and Epidemiologic Characteristics Cannot Distinguish Community-Associated Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Infection from Methicillin-Susceptible S. aureus Infection: A Prospective Investigation. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2007 Feb 15;44(4):471–482. doi: 10.1086/511033. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Naimi TS, LeDell KH, Como-Sabetti K, Borchardt SM, Boxrud DJ, Etienne J, et al. Comparison of community- and health care-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. JAMA. 2003 Dec 10;290(22):2976–2984. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.22.2976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malcolm B. The rise of methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus in U.S. correctional populations. J Correct Health Care. 2011 Jul;17(3):254–265. doi: 10.1177/1078345811401363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morrison-Rodriguez SM, Pacha LA, Patrick JE, Jordan NN. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections at an Army training installation. Epidemiol Infect. 2010 May;138(5):721–729. doi: 10.1017/S0950268810000142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.David MZ, Mennella C, Mansour M, Boyle-Vavra S, Daum RS. Predominance of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus among Pathogens Causing Skin and Soft Tissue Infections in a Large Urban Jail: Risk Factors and Recurrence Rates. J Clin Microbiol. 2008 Oct 1;46(10):3222–3227. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01423-08. 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Minton TD. Jail Inmates at Midyear 2010 - Statistical Tables: Bureau of Justice Statistics. Justice USDo. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Molinari NA, Ortega-Sanchez IR, Messonnier ML, Thompson WW, Wortley PM, Weintraub E, et al. The annual impact of seasonal influenza in the US: measuring disease burden and costs. Vaccine. 2007 Jun 28;25(27):5086–5096. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scharff RL. Health related costs: from foodnorne illness in the United States. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee GM, Lett S, Schauer S, LeBaron C, Murphy TV, Rusinak D, et al. Societal costs and morbidity of pertussis in adolescents and adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2004 Dec 1;39(11):1572–1580. doi: 10.1086/425006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang X, Meltzer MI, Pena CA, Hopkins AB, Wroth L, Fix AD. Economic impact of Lyme disease. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006 Apr;12(4):653–660. doi: 10.3201/eid1204.050602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cataldo MA, Taglietti F, Petrosillo N. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: a community health threat. Postgrad Med. 2010 Nov;122(6):16–23. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2010.11.2218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baggett HC, Hennessy TW, Rudolph K, Bruden D, Reasonover A, Parkinson A, et al. Community-onset methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus associated with antibiotic use and the cytotoxin Panton-Valentine leukocidin during a furunculosis outbreak in rural Alaska. J Infect Dis. 2004 May 1;189(9):1565–1573. doi: 10.1086/383247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rybak MJ, LaPlante KL. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: a review. Pharmacotherapy. 2005 Jan;25(1):74–85. doi: 10.1592/phco.25.1.74.55620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee BY. Digital decision making: computer models and antibiotic prescribing in the twenty-first century. Clin Infect Dis. 2008 Apr 15;46(8):1139–1141. doi: 10.1086/529441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.