Abstract

Purpose

There have been many studies concerning the associations of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) I/D, angiotensinogen (AGT) M235T polymorphisms with pregnancy induced hypertension (PIH) among Chinese populations. However, the results were inconsistent, prompting the necessity of meta-analysis.

Methods

Studies published in English and Chinese were mainly searched in EMbase, PubMed and CBM up to January 2012.

Results

Twenty-three studies with 3,551 subjects for ACE I/D and seven studies with 1,296 subjects for AGT M235T were included. Significant associations were found between ACE I/D and PIH under dominant, recessive and allelic models. A separate analysis confined to preeclampsia suggested that ACE I/D was associated with preeclampsia under recessive model and allelic model, but not dominant model. Stratified analyses were conducted as meta-regression analysis indicated that the sample size of case group was a significant source of heterogeneity, which suggested no significant association between ACE I/D and PIH in the subgroup of more than 100 cases. Associations were found between AGT M235T and PIH under dominant genetic model (OR = 1.59; 95 %CI: 1.04–2.42), recessive genetic model (OR = 1.60; 95 %CI: 1.07–2.40), and allelic model (OR = 1.40; 95 %CI: 1.17–1.68). No publication bias was found in either meta-analysis.

Conclusions

The present meta-analysis suggested significant associations between ACE I/D, AGT M235T and PIH in Chinese populations. However, no significant association was found between ACE I/D and PIH in the subgroup of more than 100 cases. Studies with larger sample sizes are necessary to investigate the associations between gene polymorphisms and PIH in Chinese populations.

Keywords: Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), Angiotensinogen (AGT), Meta-analysis, Polymorphism, Pregnancy induced hypertension (PIH)

Introduction

Pregnancy induced hypertension (PIH), defined as a condition in pregnant women with elevated systolic (≥140 mmHg) or diastolic (≥90 mmHg) blood pressure on at least two occasions 6 h apart, generally occurs after 20 weeks of gestation and returns to normal 12 weeks postpartum. PIH is the most common obstetrical complication of pregnancy, as well as a leading cause of maternal and perinatal mortality and morbidity. The incidence of PIH is 9 %, and the mortality is 3.3/100,000 in China [1], that exerts a great burden on medical and social expenditures.

Research supports the etiology and pathogenesis of PIH being due to the interaction of genetic and environmental factors. The renin-angiotensin system (RAS) plays a pivotal role in the regulation of blood pressure and electrolyte balance [2]. RAS consists of renin, angiotensinogen (AGT), angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE), two major types of angiotensin receptors (AT1R, AT2R), etc. Studies have demonstrated that RAS components experience major changes during a normal pregnancy: the excretion of AGT and angiotensin II (ANG II) increases while the level of serum ACE decreases. Comparing with normotensive pregnant women, the ACE level of PIH patients is approximately at the same level as before pregnancy, while their renin and ANG II level become lower [3]. The alterations of these vasoactive elements indicated that RAS might play a crucial role in the development of PIH [4]. Thus, extensive studies have been carried out to investigate the associations between RAS related gene polymorphisms and PIH.

AGT, the precursor of angiotensin peptides, is cleaved to angiotensin I by renin, and then Angiotensin I is converted into bioactive angiotensin II by ACE, which is the major enzyme of RAS [5]. ACE I/D (rs4646994) and AGT M235T (rs699) are two of the most frequently investigated RAS related gene polymorphisms. ACE I/D corresponds to either the presence (insertion, I) or absence (deletion, D) of a 287 bp Alu repeat in intron 16 on chromosome 17; the polymorphism of AGT M235T is a replacement of methionine by threonine at amino-acid position 235. Although extensive investigations had been taken to evaluate the associations of ACE I/D and/or AGT M235T with PIH in Chinese populations, the results were inconsistent with each other.

A meta-analysis, which was based on an ethnically mixed population, reported there were significant associations between preeclampsia and ACE I/D, AGT M235T in 2006 [6]. However, this analysis included only one study of Chinese population. Evidence has shown the distributions of genes polymorphism are various in different ethnic groups, for example the frequency of the T235 allele in Australians and Chinese population are of big difference [7]. Studies also found that the incidence of ACE gene deletion varies among different study populations and geographic regions [8]. Results drawn from the previous meta-analysis may not be appropriate for Chinese populations, thus we aimed to conduct a meta-analysis investigating the associations between the gene polymorphisms of ACE I/D, AGT M235T and PIH in Chinese populations in the current study.

Methods

Data sources

PubMed, EMbase, and CBM (China Biological Medicine), as the main sources used, were searched up to January 2012. The preliminary terms used for searching were “pregnancy induced hypertension”, “preeclampsia”, “eclampsia”, “ACE”, “angiotensin-converting enzyme”, “AGT”, “angiotensinogen”, “gene polymorphism”, and “Chinese” in MeSH terms, and language searched was limited to English and Chinese. Additional searching was performed using CNKI (National Knowledge Infrastructure), WANFANG databases, and Google Scholar to avoid inadvertent omissions. Further, relevant researches and references cited in these publications were also searched to complement the analysis.

Study selection

Inclusion criteria were set as follows: (1) Articles reported associations between PIH and ACE I/D and/or AGT M235T; (2) Studies based on case–control design with clear diagnostic criteria. PIH was diagnosed for blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg, and returned to normal 12 weeks postpartum; mild preeclampsia was defined for BP ≥ 140/90 mmHg with proteinuria ≥300 mg/24 h, and severe preeclampsia was diagnosed as BP ≥ 160/110 mmHg and proteinuria ≥2.0 g/24 h with additional symptoms and medical signs; eclampsia was diagnosed for tonic–clonic seizures in pregnant women with high blood pressure and proteinuria; (3) Genotype frequencies were reported in both case and control groups. Methods used for genotyping were validated, and subjects were unrelated individuals.

Exclusion criteria were defined as follows: (1) studies with only allele frequencies reported; (2) studies with smaller data sets were excluded for duplicate publications; (3) the distributions of genotype frequency were deviated from Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium (HWE) in control groups; (4) subjects enrolled in the studies having other diseases (cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, renal disease, or other pregnancy complications).

Data extraction

The following information were extracted from each publication including the name of first author, year of publication, location, age, gestational weeks, parity, sample size, and distributions of genotype and allele frequencies in both case and control groups. All information was checked and collected by two researchers independently, and the inconsistencies were examined and discussed until a unanimous interpretation was reached. The citations were ordered by the year of publications in tables.

Statistical analysis

Genetic model statistic analysis

HWE test was calculated with chi-square goodness of fit by two researchers when the original studies did not report this information. If the distributions of genotype frequency were inconsistent with HWE in control group, the study was excluded from further analysis. The associations of the two gene polymorphisms with PIH were evaluated under the dominant genetic model, recessive genetic model, and allelic model. Heterogeneity in meta-analysis was estimated with the I2 test (when I2 > 50 %, it was considered that there was a significant heterogeneity between studies) and chi-square-based Q statistic (p value <0.05 was used). A random effect model (DerSimonian-Laird method) was applied instead of a fixed effect model (Mantel-Haenszel method) when heterogeneity was evident.

Cumulative meta-analysis and sensitivity analysis

Cumulative meta-analysis was conducted according to the year of publication in order to identify the influence of the first published study on the subsequent publications, and evaluate the stability of the effect estimations over time. To identify potential influential studies, sensitivity analysis was carried out to check whether any of these studies would bias the overall estimation under either genotypic models or the allelic model.

Meta-regression and subgroup analysis

Meta-regression was applied to explore the source of between-study heterogeneity when the number of recruited studies was more than ten [9, 10]. Detailed information which could be retrieved from all original articles, such as the year of publication, sample size of case group, sample size of total study subjects, parity and geographic region (southern versus northern: demarcating by the Qinling Mountains of China’s Huaihe River), were taken into consideration for explaining the heterogeneity. Further, stratified analysis was conducted if there were any variables found as significant sources of heterogeneity (PHet = 0.05).

Publication bias

Evidence of publication bias was examined by a visual inspection of funnel plots, and Egger’s test was used to measure the asymmetry of funnel plot.

All the above mentioned analyses were performed by STATA 11.0, P value less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

ACE I/D

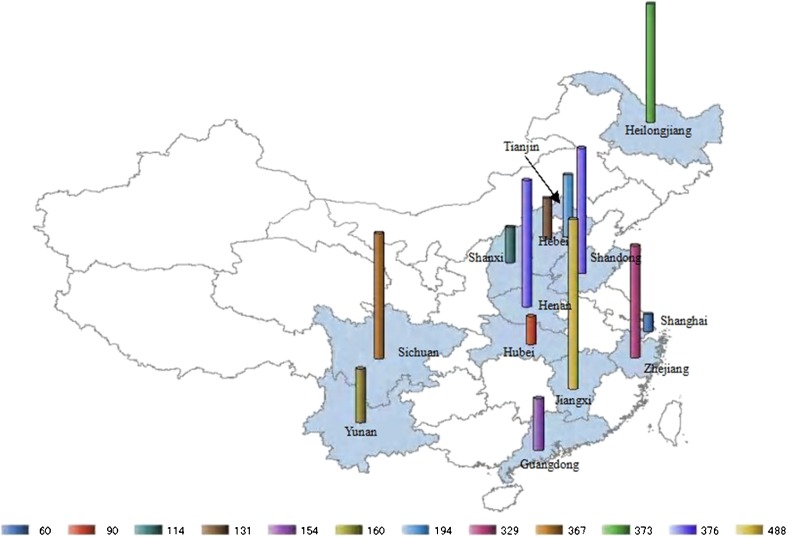

The literature search generated two English papers and 42 Chinese papers for the association studies between ACE I/D and PIH. Among these 44 articles, six articles were excluded for the deviation from HWE; eight studies were duplicated publications with the same population; and another seven papers were excluded for non-compliance with the design, such as studying the association of fetal genotype and PIH, testing the genotype using the tissue of placenta maternal site, etc. Finally, 23 articles, involving 1,684 patients and 1,867 controls, met the selection criteria. In the 23 studies, patients in seven studies were of preeclampsia [11–17]. Cases in the other 16 studies were the mixture of gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, and eclampsia patients, which we failed to retrieve genotype data for different diseases in the original studies. The characteristics of the included studies and women were shown in Tables 1 and 2, and the geographical distributions of the subjects from 13 provinces in China were shown in Fig. 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies for ACE I/D and PIH

| Author | Year | Location | Enrollment | Cases | Controls | Parity | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhu [18] | 1998 | Shanghai | 1994–1995 | 35 | 25 | primiparity | Singleton, excluded other pathologies |

| Zhou [19] | 1999 | Shandong | 1995.9–1998.8 | 60 | 76 | primiparity | Singleton, excluded other pathologies |

| Wang [20] | 1999 | Heibei | 1996.12–1997.8 | 61 | 70 | N | Excluded other pathologies |

| Hong [21] | 2000 | Zhejiang | 1997.12–1998.6 | 52 | 100 | N | Excluded other pathologies |

| Bai [22] | 2002 | Sichuan | 1998.8–2000.5 | 81 | 205 | N | Han ethnic, no family history, excluded other pathologies |

| Gao [23] | 2002 | Heilongjiang | 2000.12–2001.3 | 110 | 81 | primiparity | Singleton, excluded other pathologies |

| Wu [24] | 2002 | Jiangxi | 1998.5–2000.12 | 56 | 52 | primiparity | Singleton, excluded other pathologies |

| Mao [25] | 2004 | Heilongjiang | 1998.1–2002.12 | 62 | 120 | primiparity | Singleton, excluded other pathologies |

| Wang [26] | 2004 | Jiangxi | 2001.9–2003.4 | 100 | 100 | N | Han ethnic, excluded other pathologies |

| Wang# [27] | 2004 | Tianjin | 2001–2003 | 41 | 50 | primiparity | Singleton, excluded other pathologies |

| Li [11] | 2005 | Shandong | 1998.8–2002.10 | 103 | 76 | primiparity | Singleton, excluded other pathologies |

| Chen [28] | 2006 | Zhejiang | 2002–2004 | 92 | 85 | N | Excluded other pathologies |

| Li [29] | 2006 | Guangdong | 2000.3–2004.3 | 54 | 100 | N | Excluded gestational diabetes and medical complications. |

| Li [12] | 2007 | Shandong | 2003.10–2006.9 | 133 | 105 | M | Han ethnic, excluded other pathologies |

| Song [13] | 2007 | Hubei | 2004.7–2005.2 | 45 | 45 | N | Exclude cardiovascular disease, nephropathy, et al. |

| Huang [30] | 2008 | Yunan | 2004.12–2007.6 | 90 | 120 | primiparity | Singleton, excluded other pathologies |

| Ren [31] | 2008 | Shanxi | 2006.8–2007.2 | 60 | 54 | primiparity | Excluded other pathologies |

| Zhan [14] | 2008 | Jiangxi | 2006.9–2007.9 | 120 | 60 | N | Excluded other pathologies |

| Cui [15] | 2008 | Tianjin | 2005.8–2006.2 | 63 | 40 | N | Singleton, excluded other pathologies. |

| Deng [16] | 2010 | Henan | 2009–8–2010.5 | 50 | 100 | N | Excluded other pathologies |

| Yue [17] | 2011 | Sichuan | 2007.3–2009.5 | 43 | 44 | N | Excluded other pathologies |

| Yan [32] | 2011 | Henan | 2008.1–2009.12 | 113 | 113 | M | Han ethnic, excluded other pathologies |

N: Not mentioned M: Cases and controls were matched. #: To distinguish the two studies with the same last name of first author

Table 2.

Characteristics of included women for ACE I/D and PIH

| Author | Age (years) | Gestational weeks (weeks) | Genotype distributions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Controls | Cases | Controls | Cases(DD/ID/II) | Controls(DD/ID/II) | |

| Zhu [18] | 26–32 | 26–32 | N | N | 23/7/15 | 21/10/13 |

| Zhou [19] | 24–32 | 24–32 | N | N | 39/12/9 | 8/32/38 |

| Wang [20] | 27.5 ± 3.7 | 27.8 ± 8.9 | 38.8 ± 4.6 | 39.5 ± 2.7 | 15/31/15 | 13/24/33 |

| Hong [21] | 23–32 | 23–32 | N | N | 34/10/8 | 16/34/50 |

| Bai [22] | 28 ± 4 | 28 ± 3 | 32∼42 | 36∼42 | 8/38/35 | 31/83/85 |

| Gao [23] | 26.7 ± 3.2 | 27.4 ± 2.8 | 38.2 ± 2.8 | 39.4 ± 1.2 | 66/34/10 | 57/18/6 |

| Wu [24] | 25 ± 5 | 25 ± 4 | 36–40 | 36–40 | 21/23/12 | 12/22/28 |

| Mao [25] | 27.8 ± 3.4 | 26.8 ± 1.8 | 38.4 ± 2.3 | 39.2 ± 1.4 | 25/24/13 | 12/46/62 |

| Wang [26] | 26.3 | 25.7 | 38.4 ± 2.9 | 39.2 ± 1.9 | 14/43/43 | 14/46/40 |

| Wang# [27] | 26 ± 4 | 25 ± 6 | 37.2 ± 2.0 | 36.4 ± 3.4 | 13/18/7 | 9/19/22 |

| Li [11] | M | M | 38.6 ± 2.6 | 39.3 ± 1.4 | 34/34/35 | 14/33/29 |

| Chen [28] | M | M | M | M | 41/31/20 | 16/34/35 |

| Li [29] | 26.8 ± 5.4 | 26.8 ± 5.4 | 35.8 ± 3.6 | N | 24/14/16 | 19/39/42 |

| Li [12] | 29 | 28 | 35.7 | 38.6 | 37/46/50 | 25/31/49 |

| Song [13] | 30.5 ± 3.7 | 28.7 ± 3.2 | 35.3 ± 3.6 | 38.9 ± 1.2 | 17/21/7 | 13/23/9 |

| Huang [30] | 29.4 ± 5.4 | 28.7 ± 4.4 | 35.3 ± 3.2 | 37.6 ± 2.4 | 46/32/12 | 21/47/52 |

| Ren [31] | 25 ± 5 | 25 ± 5 | 36 ± 3 | 39 ± 3 | 27/20/13 | 13/17/24 |

| Zhan [14] | N | N | N | N | 32/41/47 | 10/24/26 |

| Cui [15] | N | 29.64 | N | N | 11/33/19 | 4/19/17 |

| Deng [16] | 30.8 ± 5.2 | 29.6 ± 3.3 | N | N | 20/16/14 | 20/57/23 |

| Yue [17] | M | M | N | N | 12/8/23 | 6/14/24 |

| Yan [32] | 30.41 ± 5.4 | 30.14 ± 5.0 | 37.6 ± 2.2 | 38.9 ± 1.4 | 21/57/35 | 23/52/38 |

N: Not mentioned #: To distinguish the two studies with the same last name of first author. M: Cases and controls were matched

Fig. 1.

Distributions of the sample source in the studies of association between ACE I/D and PIH. The study subjects were selected from 13 provinces and study size was marked by cylinder of different colors and heights, the number of participants from each province was shown below the map

Genetic model statistic analysis

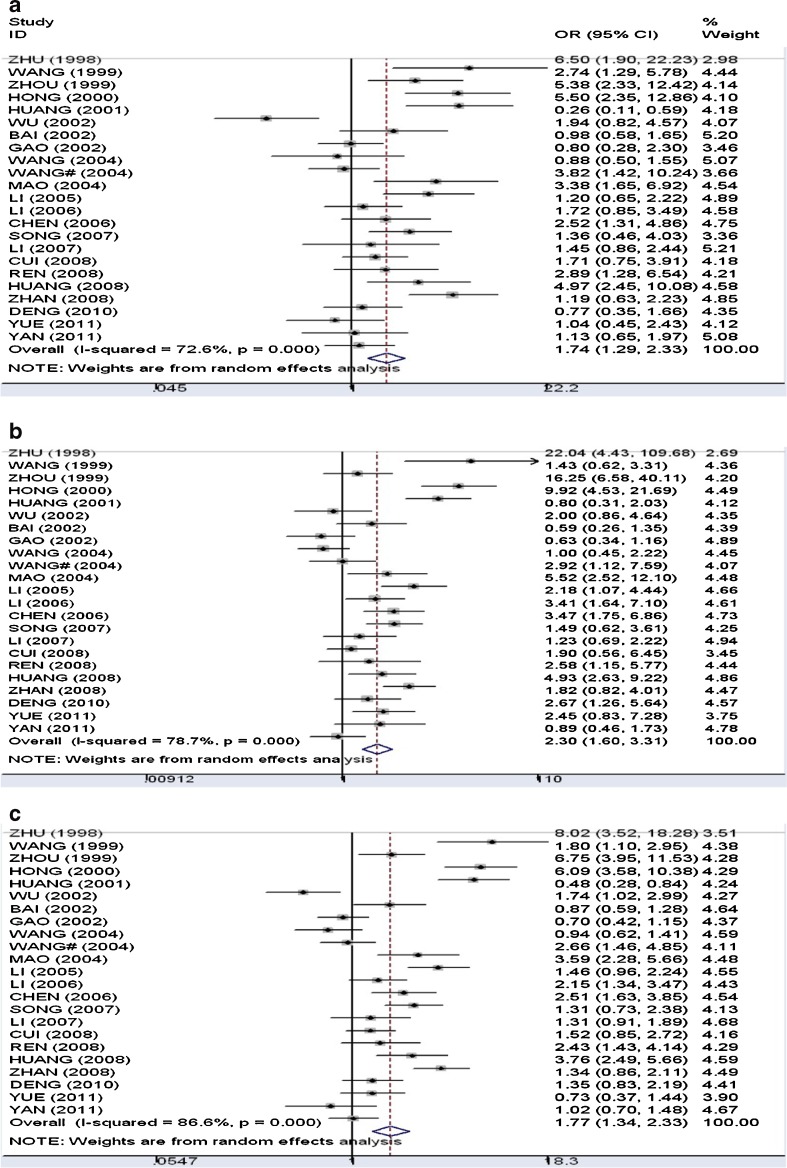

Figure 2 presented the forest plots of the meta-analyses. (a) Dominant genetic model (DD+ID versus II): The overall odds ratio under the random-effect model was 1.74 (95 %CI: 1.29–2.33), and between-study heterogeneity was significant (I2 = 72.6 %). (b) Recessive genetic model (DD versus ID+II): The pooled odds ratio under the random-effect model (I2 = 78.7 %) was 2.31 (95 %CI: 1.61–3.31). (c) Allelic model (D versus I): The pooled odds ratio under the random effect model (I2 = 86.6 %) was 1.77 (95 %CI: 1.34–2.33).

Fig. 2.

Forest plots of meta-analysis of the association between ACE I/D and PIH. a Dominant genetic model (the random effect model); b Recessive genetic model (the random effect model); c Allelic model (the random effect model)

A separate analysis confined to cases of preeclampsia was carried out. Significant associations were found under recessive genetic model (OR = 1.81, 95 %CI: 1.34–2.44) and allelic model (OR = 1.31, 95 %CI: 1.09–1.57), but not dominant genetic model (OR = 1.23, 95 % CI: 0.94–1.60). Between-study heterogeneity and publication bias were not found in the above models.

Cumulative meta-analysis and sensitivity analysis

In cumulative meta-analyses, the pooled odds ratio showed stable following the year 2004 for both genotypic models and the allelic model, and the associations reached significance with the accumulation of data over time (figures not shown). Sensitivity analysis showed none of the single studies influenced the overall odds ratio significantly (figures not shown).

Meta-regression and subgroup analysis

In meta-regression analysis, only the sample size of the case group was identified as a significant source of heterogeneity (PHet = 0.18, 0.02, and 0.09 under the dominant genetic model, recessive genetic model and allelic model, respectively). Stratified analyses were conducted by dividing the studies into three groups according to the sample size of case group (cases < 50, 50 < =cases < 100 and cases > =100). The summarized results were presented in Table 3. The results revealed that the pooled odds ratio decreased as the study size of case group increased under both genotypic models and allelic model. No significant association was found between ACE I/D and PIH in the subgroup with more than 100 cases.

Table 3.

Subgroup analyses results of different study size of case group for ACE I/D with PIH

| Models | OR, 95 %CI (cases < 50) | OR, 95 %CI (50 < =cases < 100) | OR, 95 %CI (cases > =100) |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 4 | n = 13 | n = 6 | |

| Dominant genetic model | 2.30 (1.00–5.30) | 2.04 (1.29–3.21) | 1.14 (0.88–1.46) |

| Recessive genetic model | 3.30 (1.32–8.26) | 2.93 (1.82–5.26) | 1.14 (0.87–1.50) |

| Allelic model | 2.01 (0.84–7.56) | 2.14 (1.45–3.16) | 1.12 (0.94–1.32) |

*n denoted the number of studies in each group

Publication bias

There was no publication bias since funnel plots didn’t show asymmetric distribution and Egger’s test was statistical insignificance (P = 0.13, 0.19, and 0.22 under the dominant genetic model, recessive genetic model and allelic model, respectively).

AGT M235T

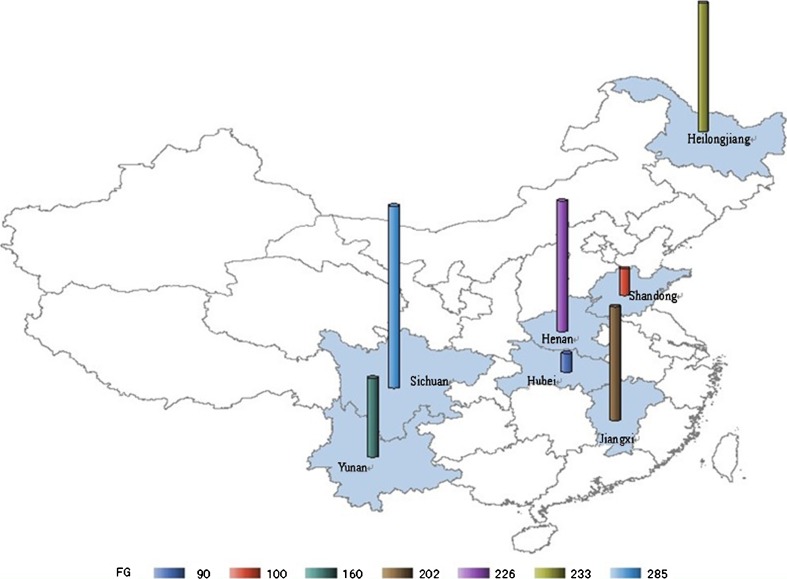

Regarding AGT M235T and PIH, the literature search resulted in two English papers and 11 Chinese papers, among which seven articles met the selection criteria. Six studies were excluded, two due to duplicated publications, one for inappropriate control group, one for incorrect data, and two for studying the other polymorphisms (T174M, 6G-A) within AGT. In the seven studies, two were focusing on preeclampsia [13, 33], and the other five were on pregnancy induced hypertension without detailed genotype data for gestational hypertension, preeclampsia and eclampsia respectively. Studies were re-calculated by the first and second author to examine HWE in control groups. The characteristics of the seven studies with 551 cases and 745 controls were shown in Tables 4 and 5, and the distributions of the participants from seven provinces in China were shown in Fig. 3.

Table 4.

Characteristics of the included studies for AGT M23T and PIH

| Author | Year | Location | Enrollment | Cases | Controls | Parity | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bai [22] | 2002 | Sichuan | 1998.8–2000.5 | 81 | 205 | N | Han ethnic, no family history, excluded other pathologies |

| Wu [34] | 2002 | Shandong | 2000.2–2001.5 | 60 | 40 | Primiparity | Singleton, excluded other pathologies |

| Fu [35] | 2003 | Jiangxi | 2001.9–2002.12 | 100 | 102 | N | Excluded other pathologies |

| Hu [36] | 2005 | Heilongjiang | 1998–2003 | 93 | 140 | N | N |

| Huang [33] | 2007 | Yunan | 2004.7–2005.12 | 58 | 102 | primiparity | Singleton, excluded other pathologies |

| Song [13] | 2007 | Hubei | 2004.7–2005.2 | 45 | 45 | N | Excluded other pathologies |

| Xiang [37] | 2011 | Henan | 2008.1–2009.12 | 113 | 113 | M | Han ethnic, excluded other pathologies |

N: Not mentioned. M: Cases and controls were matched

Table 5.

Characteristics of the included women for AGT M23T and PIH

| Author | Age (years) | Gestational weeks (weeks) | Genotype distribution | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Controls | Cases | Controls | Cases (TT/MT/MM) | Controls (TT/MT/MM) | |

| Bai [22] | 28 ± 3 | 28 ± 4 | 32–42 | 36–42 | 58/21/1 | 148/41/6 |

| Wu [34] | 27.9 ± 3.4 | 28.1 ± 3.2 | 36.7 ± 4.5 | 37.2 ± 4.2 | 34/22/4 | 12/23/5 |

| Fu [35] | 26.3 ± 2.1 | 25.7 ± 2.5 | N | N | 53/42/7 | 30/57/13 |

| Hu [36] | M | M | M | M | 69/22/2 | 81/56/3 |

| Huang [33] | 29 ± 4 | 29 ± 3 | 28–36 | 28–36 | 14/31/13 | 25/50/27 |

| Song [13] | 30.5 ± 3.7 | 28.7 ± 3.2 | 35.32 ± 3.6 | 38.96 ± 1.2 | 15/23/7 | 7/25/13 |

| Xiang [37] | 30.41 ± 5.4 | 30.14 ± 5.0 | 37.56 ± 2.2 | 38.90 ± 1.3 | 59/48/6 | 63/43/7 |

N: Not mentioned. M: Cases and controls were matched

Fig. 3.

Distributions of the sample source in the studies of the association between AGT M235T and PIH. The participants were selected from seven provinces and study size was marked by cylinders of different colors and heights, and the number of participants from each province was shown below the map

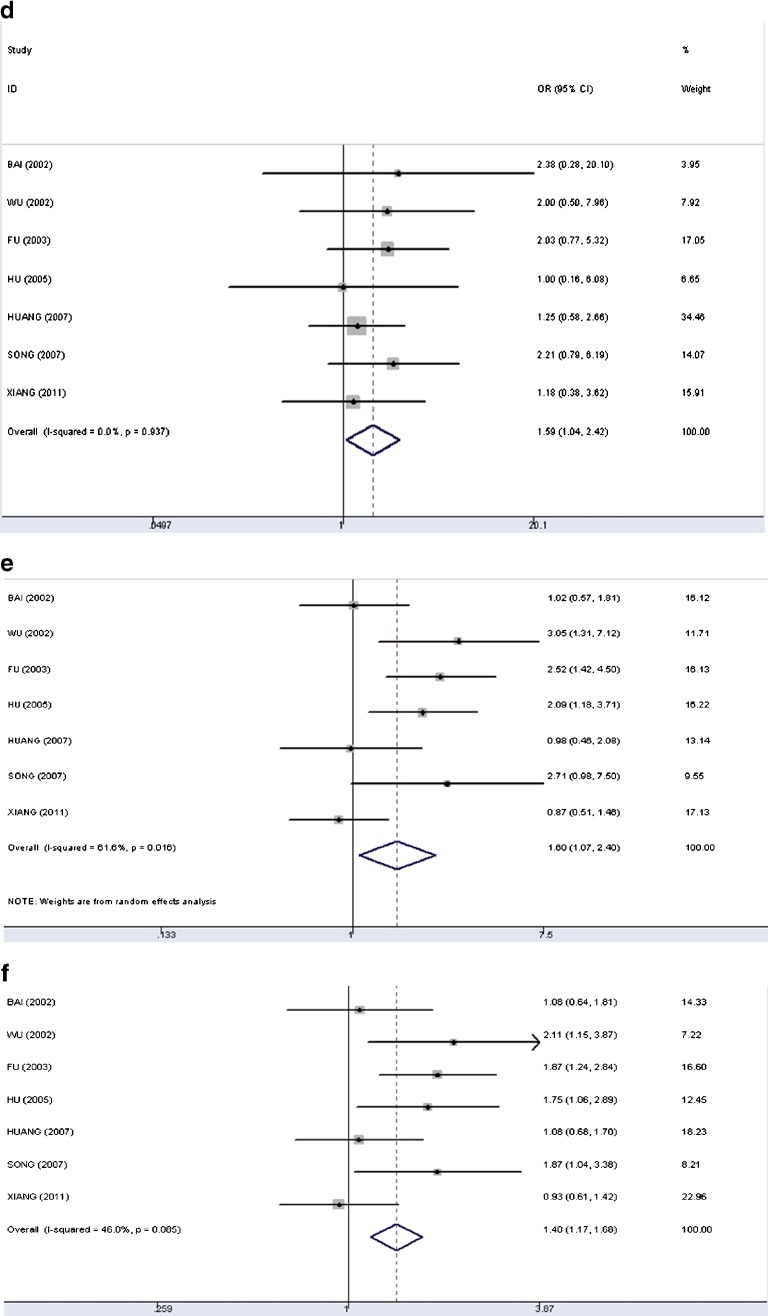

Genetic model statistic analysis

Figure 4 showed the forest plots of meta-analyses, (d) Dominant genetic model (TT+MT versus MM): the pooled odds ratio under the fixed-effects model was 1.59 (95 %CI: 1.04–2.42). The test for heterogeneity was not significant (I2 = 0); (e) Recessive genetic model (TT versus MT+MM): the pooled odds ratio under the random-effects model was 1.60 (95 %CI: 1.07–2.40). The overall data indicated significant heterogeneity (I2 = 62 %); (f) Allelic model (T versus M): the pooled odds ratio was 1.40 (95 %CI: 1.17–1.68) under the fixed-effects model (I2 = 46 %). Due to the limited studies of AGT M235T and preeclampsia, we failed to conduct a separate analysis in this regard.

Fig. 4.

Forest plots of meta-analysis of the association between AGT M235T and PIH. d Dominant genetic model (the fixed-effect model); e Recessive genetic model (the random-effect model); f Allelic model (the fixed-effect model)

Cumulative meta-analysis and sensitivity analysis

In cumulative meta-analyses, the pooled ORs for both genotypic models and the allelic model were stable following the year 2005 (figures not shown). Sensitivity analysis and meta-regression were not performed since less than ten studies were included in the current analysis.

Publication bias

Asymmetric distribution was not found in funnel plots, and Egger’s test showed statistical insignificance under the dominant genetic model, recessive genetic model and allelic model (P = 0.68, 0.34, and 0.31, respectively) (figures not shown).

Discussion

Many studies investigating the etiology and pathogenesis of PIH suggested an inherited susceptibility. Renin, AGT and ACE are three important components in RAS, each playing a critical role in the regulation of blood pressure and electrolyte balance. Renin enzymatically cleaves AGT to angiotensin I, which is the rate-limiting step of the RAS cascade. However, very few studies have been carried out to investigate the relationship for gene polymorphisms of renin with PIH in Chinese populations so that we failed to conduct a meta-analysis in this aspect. ACE I/D and AGT M235T are the most frequently studied ones of RAS associated with PIH. However, studies had inconsistent conclusions, which suggested a meta-analysis necessary to assess the genetic effects of ACE I/D and AGT M235T on PIH.

Previous meta-analyses in this regard were mainly based on mixed populations. Studies showed that the distribution of gene polymorphisms differed among different ethnic populations. The result of a meta-analysis is likely to be affected by the population sources of study subjects, and thus the conclusions drawn from studies based on other populations may not be appropriate for a specific population [38]. It is necessary to conduct a meta-analysis to evaluate the associations between ACE I/D, AGT M235T, and PIH among Chinese populations.

Significant associations were found in meta-analysis of ACE I/D and PIH under the genotypic models and allelic model in the present study. A separate analysis for ACEI/D with preeclampsia was carried out, and significant associations were found under recessive genetic and allelic models, but not dominant genetic model. Further, meta-regression analyses revealed that sample size of case group was a significant source of heterogeneity in current analysis. A stratified analysis showed a diminished effect as the number of cases increased, and no significant association was found in the subgroup with large case numbers either under genotypic models or allelic model. Previous meta-analysis based on mixed populations concluded that ACE I/D was associated with PIH only under the recessive genetic model, which was inconsistent with the current findings. The finding from current study demonstrated the conclusion drawn by Norma C. Serrano and his colleagues, which indicated the small increased risk of preeclampsia associated with ACE-D allele might be due to the small study bias [39]. Small sample sized studies were more likely to exaggerate the genetic effect, which was actually small [40]. Most studies conducted in Asian populations with the number of cases less than 100 tended to have larger ORs, and Chinese studies typically suggested even a stronger genetic effect than non-Chinese studies [41].

Significant heterogeneity was presented in the current meta-analysis of association between ACE I/D and PIH, which several reasons may account for: (1) Disease severity may serve as a confounder in the studies of the association between gene polymorphisms and PIH, and recent studies reported that a stronger genetic effect was found in severe cases of PIH in comparison with mild cases [42]. The effects of genetic and environmental varied in the development of preeclampsia and gestational hypertension. Studies suggested that the two diseases should be analyzed separately for their different gene markers [43]. However, most studies carried out in China on associations between gene polymorphisms and PIH did not differentiate preeclampsia and gestational hypertension in analysis. (2) Environmental factors were not taken into analysis although the occurrence of PIH is the result of the interaction of genetic and environmental factors. In the present meta-analysis, the distribution of study subjects ranged from northeast to southwest in China. Environmental factors, living habits, and economic situations varied a lot among those populations, which could influence the evaluation of the associations. (3) Early-onset preeclampsia and late-onset preeclampsia, which were found to be associated with different biomarkers, genetic and environmental risk factors, should also be considered for interpreting the source of heterogeneity [44, 45].

Significant associations of AGT M235T with PIH were found under both the dominant genetic model and recessive genetic model, individuals with allele T would be at a higher risk of developing PIH in the present meta-analysis, which was consistent with the previous meta-analysis conducted by Medica I and his colleagues, based on mixed populations. A meta-regression analysis with 1,446 cases and 3,829 controls in 2008 revealed that individuals carrying TT were more likely to develop preeclampsia or eclampsia compared to those with MM in Caucasians, but not in East Asian population. It might be due to this study having very limited numbers of studies of East Asian population [46]. A large scale study with 1,068 Caucasian women concluded that AGT M235T might contribute to the pathogenesis of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia [47]. However, a literature review by Elke Knyrim in 2008 [48] reported that most of the studies, including a British multi-centre GOPEC study [49], did not support this association. The current results from studies of Chinese populations should be viewed cautiously and need to be further investigated with a larger sample size in the future.

The current study was the first meta-analysis studying the associations between ACE I/D, AGT M235T and PIH specifically on a Chinese population. Although no evidence of publication bias was found in the current analysis, conclusions should be drawn cautiously. The sample size in the current study was relatively small. We have over 90 % power to detect an increased odds ratio of 0.3 for ACE I/D (MAF: D = 0.399) and over 80 % power to detect the odds ratio of 1.40 for AGT M235T in the present study. Studies with a small sample size usually lack sufficient power to detect the real associations [50], and evidence also showed that some significant gene-disease associations revealed by meta-analysis based on small sample sized studies had been refuted by later large-scale studies [51]. Thus, it is necessary to conduct large-scale researches in the future study of PIH. Furthermore, recent studies supported that uteroplacental renin-angiotensin system also plays an important role in the development of PIH, and that RAS related gene polymorphisms of fetuses as well as fetal-maternal genotype incompatibility might be one of the potential mechanisms of pregnancy complications [52–54]. It is suggested that fetal genotypes should also be examined in the future genetic studies of PIH, besides maternal genotypes.

The current meta-analysis suggested significant associations between ACE I/D, AGT M235T, and PIH in Chinese populations. However, the results of stratified analysis of ACE I/D and PIH suggested that the apparent significance of the result may be due to small sample size. It is necessary to conduct large sample sized studies in the future; in addition, the genetic polymorphisms in both mother and fetus need to be investigated together.

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by National Nature Science Foundation of China [grant numbers: 3070068/H2610 and 81172679/H2605].

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Capsule

ACE I/D and AGT M235T were associated with PIH in Chinese, however the association became insignificant for ACE I/D in subgroup with a large sample size

Contributor Information

Ming Zhu, Email: zhuming0310@gmail.com.

Jie Zhang, Email: ashleycheung@foxmail.com.

Shaofa Nie, Email: sf_nie@126.com.

Weirong Yan, Phone: +86-27-83650713, FAX: +86-27-83657765, Email: weirongy@gmail.com, Email: weirongy@hotmail.com.

References

- 1.Ministry of Health PRC. Chinese Health Statistical Digest 2010. http://www.moh.gov.cn/publicfiles/business/htmlfiles/zwgkzt/ptjnj/year2010/2010t7/sheet001.htm Accessed 21 March 2012.

- 2.Irani RA, Xia Y. The functional role of the renin-angiotensin system in pregnancy and preeclampsia. Placenta. 2008;29:763–771. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anton L, Brosnihan KB. Systemic and uteroplacental renin-angiotensin system in normal and pre-eclamptic pregnancies. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis. 2008;2:349–362. doi: 10.1177/1753944708094529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Velloso EP, Vieira R, Cabral AC, Kalapothakis E, Santos RA. Reduced plasma levels of angiotensin-(1-7) and renin activity in preeclamptic patients are associated with the angiotensin I-converting enzyme deletion/deletion genotype. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2007;40:583–590. doi: 10.1590/S0100-879X2007000400018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shah DM. The role of RAS in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2006;8:144–152. doi: 10.1007/s11906-006-0011-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Medica I, Kastrin A, Peterlin B. Genetic polymorphisms in vasoactive genes and preeclampsia: a meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2007;131:115–126. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guo G, Wilton AN, Fu Y, Qiu H, Brennecke SP, Cooper DW. Angiotensinogen gene variation in a population case-control study of preeclampsia/eclampsia in Australians and Chinese. Electrophoresis. 1997;18:1646–1649. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150180929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gurdol F, Isbilen E, Yilmaz H, Isbir T, Dirican A. The association between preeclampsia and angiotensin-converting enzyme insertion/deletion polymorphism. Clin Chim Acta. 2004;341:127–131. doi: 10.1016/j.cccn.2003.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmid CH, Stark PC, Berlin JA, Landais P, Lau J. Meta-regression detected associations between heterogeneous treatment effects and study-level, but not patient-level, factors. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:683–697. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Higgins J, Thompson S, Deeks J, Altman D. Statistical heterogeneity in systematic reviews of clinical trials: a critical appraisal of guidelines and practice. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2002;7:51–61. doi: 10.1258/1355819021927674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li D, Ma Y, Jiang H, Liu C, Li H, Wang R, et al. The association between polymorphisms of angiotensin-converting enzyme and apolipoprotein B and left ventricular hypertrophy in patients with preeclampsia and eclampsia. Xian Dai Fu Chan Ke Jin Zhan. 2005;14:108–114. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li H, Ma Y, Fu Q, Wang L. Angiotensin-converting enzyme insertion/deletion (ACE I/D) and angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1R) gene polymorphism and its association with preeclampsia in Chinese women. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2007;26:293–301. doi: 10.1080/10641950701413676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Song C, Xie S, Tang Y, Wang J, Lian J, Yang L, et al. The gene polymorphisms of the rein-angiotensin system in preeclampisa. Shi Yong Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2007;23:354–357. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhan WX, Zheng JS. Relationship between angiotensin converting enzyme gene polymorphism and severe preeclampsia and preeclampisa complication renal dysfunction. Jiang Xi Yi Yao. 2008;43:782–784. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cui HY, Chen S. Relationship between angiotensin converting enzyme gene polymorphism and early-onset severe preeclampsia. Zhong Guo Fu You Bao Jian. 2008;23:1545–1546. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deng J, You FZ, Cheng GM, Xu YJ. Correlation between gene polymorphisms of ACE, AT1R, eNOS and severe pre-eclampsia. Zhong Guo Fu You Bao Jian. 2010;25:5277–5279. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yue BM, He GL, Liu XH. Polymorphisms of angiotensin-converting enzyme gene in pre-eclampsia. Med J West China. 2011;23:850–853. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu M, Xia Y, Cheng W, Weng H, Zhang Z. Study on a deletion polymorphism of the angiotensin converting enzyme gene in pregnancy induced hypertension. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 1998;33:83–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou N, Yu P, Chen J, Huang H, Jiang S. Detection of insertion/deletion polymorphism of angiotensin converting enzyme gene in preeclampsia. Zhonghua Yi Xue Yi Chuan Xue Za Zhi. 1999;16:29–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang G, Hua F, Niu J, Li H, Dai Q, Wang J, et al. Relationship of gene polymorphism of angiotensin-converting enzyme and pregnancy induced hypertension. Zhonghua Fu Chang Ke Za Zhi. 1999;34:116. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hong W, Lin X, Xu Y, Wang Q, Hu Y, Chen Y, et al. Study on insertion/deletion polymorphis of angiotensin-converting enzyme and pregnancy induced hypertension. Wen Zhou Yi Xue Yuan Xue Bao. 2000;30:37–38. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bai H, Liu X, Liu R, Liu Y, Li M, Liu B. Angiotensinogen and angiotensin-I converting enzyme gene variations in Chinese pregnancy induced hypertension. Hua Xi Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2002;33:233–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gao X, Qiu X, Ye F, Chen L, Xing L, Zhang W. Study on insertion/deletion polymorphism of angiotensin-converting enzyme in women with pregnancy induced hypertension. Zhong Guo Fu You Bao Jian. 2002;17:738–740. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu Y, Chen K, Su H, Chen X, Wu Q, Zhen J, et al. Relationship of gene polymorphism of angiotensin-converting enzyme and the morbidity of pregnancy induced hypertension Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi 2002373011953062 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mao D, Li K, Zhao Y, Chen L, Chen S. Study on MTHFR gene and ACE gene polymorphisms in pregnancy induced hypertension. Zhong Hua Wei Chang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2004;7:22–24. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang J, Bu T, Wang Y, Chen P. Relationship between insertion/deletion polymorphism of angiotensin converting enzyme gene and pregnancy-induced hypertension syndrome. Tian Jin Yi Yao. 2004;32:339–341. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang C, Fu F, Liao D. Study on detection of insertion/deletion polymorphism of angiotensin-converting enzyme gene in pregnancy induced hypertension. Jiang Xi Yi Xue Yuan Xue Bao. 2004;44:77–81. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen B, Zhuo J, Zhou L. Study on the polymorphism of angiotensin I-convertin enzyme gene in pregnancy-induced hypertension syndrome. Jian Yan Yi Xue. 2006;21:39–41. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li J, Huang Y, Liu X. Study on a deletion polymorphism of the angiotensin-converting enzyme gene in pregnancy induced hypertension. Guang Zhou Yi Xue Yuan Xue Bao. 2006;34:45–52. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang Y, Feng Y, Zhu Y, Zuo X. The investigation of gene polymorphisms of angiotensin converting enzyme in family of hypertensive disorder complicating pregnancy. Contemp Med. 2008:8–10

- 31.Ren H, Chen B, Liu S, Zhao L, Bo L. Correlation between polymorphism of angiotensin converting enzyme gene and hypertensive disorder complicating pregnancy. Di Si Jun Yi Da Xue Xue Bao. 2008;29:434–436. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yan W, Kulane A, Xiang P, Li Z, Di H, Nie S. Maternal and fetal angiotensin-converting enzyme gene insertion/deletion polymorphism not associated with pregnancy-induced hypertension in Chinese women. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Huang Y, Li Y, Shao J, Sun L. The relationship of polymorphism of RAS genes and interaction with preeclampisa. Yun Nan Yi Yao. 2007;28:8–11. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu Z, Jiang H, Wang L, Chen X. The association of angiotensinogen M235T with pregnancy induced hypertension. Zhong Hua Yi Xue Yi Chuan Xue Za Zhi. 2002;19:528–529. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fu F, Chen Q, Cao Q, He X, Zhang W. The association of gene mutation AGT M235T with pregnancy induced hypertension syndrome. Zhong Hua Lin Chuang Yi Xue Yan Jiu Za Zhi 2003:13191–13192

- 36.Hu Y, Wang D, Wu Y. Study on relationship of gene mutation of angiotensinogen with the morbidity of pregnancy induced hypertension. Zhong Guo Shi Yong Fu Ke Yu Chang Ke Za Zhi. 2005;21:315. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xiang P, Li Z, Di H, Nie S, Yan W. The associations between maternal and fetal angiotensinogen M235T polymorphism and pregnancy-induced hypertension in Chinese women. Reprod Sci. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Akbar SA, Khawaja NP, Brown PR, Tayyeb R, Bamfo J, Nicolaides KH. Angiotensin II type 1 and 2 receptors gene polymorphisms in pre-eclampsia and normal pregnancy in three different populations. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2009;88:606–611. doi: 10.1080/00016340902859307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Serrano NC, Diaz LA, Paez MC, Mesa CM, Cifuentes R, Monterrosa A, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme I/D polymorphism and preeclampsia risk: evidence of small-study bias. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e520. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ioannidis JP, Trikalinos TA, Ntzani EE, Contopoulos-Ioannidis DG. Genetic associations in large versus small studies: an empirical assessment. Lancet. 2003;361:567–571. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12516-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pan Z, Trikalinos TA, Kavvoura FK, Lau J, Ioannidis JP. Local literature bias in genetic epidemiology: an empirical evaluation of the Chinese literature. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e334. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lin J, August P. Genetic thrombophilias and preeclampsia: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:182–192. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000146250.85561.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salonen RH, Lichtenstein P, Lipworth L, Cnattingius S. Genetic effects on the liability of developing pre-eclampsia and gestational hypertension. Am J Med Genet. 2000;91:256–260. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(20000410)91:4<256::AID-AJMG3>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Uma R, Forsyth SJ, Struthers AD, Fraser CG, Godfrey V, Murphy DJ. Polymorphisms of the angiotensin converting enzyme gene in early-onset and late-onset pre-eclampsia. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010;23:874–879. doi: 10.3109/14767050903456667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Raymond D, Peterson E. A critical review of early-onset and late-onset preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2011;66:497–506. doi: 10.1097/OGX.0b013e3182331028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zafarmand MH, Nijdam ME, Franx A, Grobbee DE, Bots ML. The angiotensinogen gene M235T polymorphism and development of preeclampsia/eclampsia: a meta-analysis and meta-regression of observational studies. J Hypertens. 2008;26:1726–1734. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3283009ca5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pfab T, Stirnberg B, Sohn A, Krause K, Slowinski T, Godes M, et al. Impact of maternal angiotensinogen M235T polymorphism and angiotensin-converting enzyme insertion/deletion polymorphism on blood pressure, protein excretion and fetal outcome in pregnancy. J Hypertens. 2007;25:1255–1261. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3280d35834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Knyrim E, Muetze S, Eggermann T, Rudnik-Schoeneborn S, Lindt R, Ortlepp JR, et al. Genetic analysis of the angiotensinogen gene in pre-eclampsia: study of german women and review of the literature. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2008;66:203–208. doi: 10.1159/000146084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Disentangling fetal and maternal susceptibility for pre-eclampsia: a British multicenter candidate-gene study. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77:127–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Cardon LR, Bell JI. Association study designs for complex diseases. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:91–99. doi: 10.1038/35052543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Keavney B, McKenzie C, Parish S, Palmer A, Clark S, Youngman L, et al. Large-scale test of hypothesised associations between the angiotensin-converting-enzyme insertion/deletion polymorphism and myocardial infarction in about 5000 cases and 6000 controls. International Studies of Infarct Survival (ISIS) Collaborators. Lancet. 2000;355:434–442. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)82009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Esplin MS, Fausett MB, Fraser A, Kerber R, Mineau G, Carrillo J, et al. Paternal and maternal components of the predisposition to preeclampsia. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:867–872. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103223441201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cnattingius S, Reilly M, Pawitan Y, Lichtenstein P. Maternal and fetal genetic factors account for most of familial aggregation of preeclampsia: a population-based Swedish cohort study. Am J Med Genet A. 2004;130A:365–371. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vefring HK, Wee L, Jugessur A, Gjessing HK, Nilsen ST, Lie RT. Maternal angiotensinogen (AGT) haplotypes, fetal renin (REN) haplotypes and risk of preeclampsia; estimation of gene-gene interaction from family-triad data. BMC Med Genet. 2010;11:90. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-11-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]