Abstract

Purpose

To report the long-term management of a case of premature ovarian insufficiency of unknown origin in a young woman with Crohn’s disease.

Method

Here is reported the case of a 20 years old woman with Cronh’s disease presenting with two years amenorrhea and FSH and LH levels of 255 mIU/ml and 182 mIU/ml respectively, who received 10 months corticosteroid treatment followed by 7 years of estro-progestin treatment.

Results

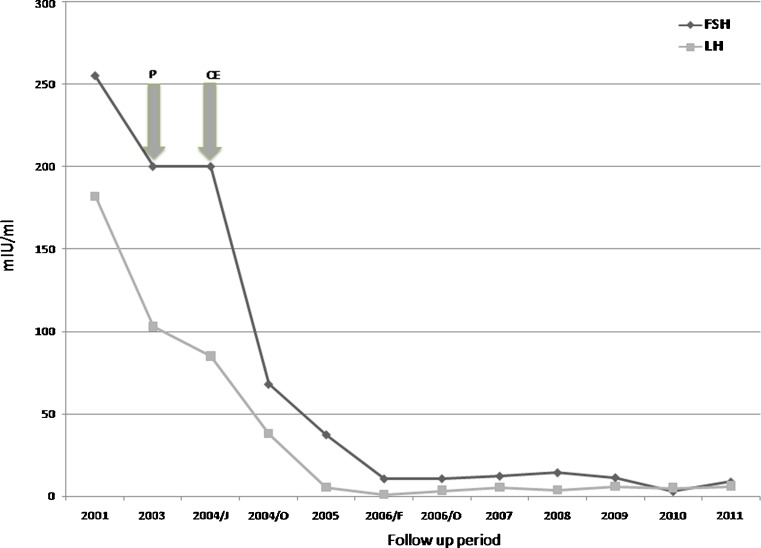

Corticosteroid treatment was ineffective in restoring patients gonadotropin levels as well as ovarian volume, while estro-progestins promoted a prompt reduction in gonadotrophin levels, which returned in the normal range after two years of treatment, as well as restoration of ovarian function, which occurred after four years of estrogens administration, as demonstrated by normal ovarian volume and ovulatory follicles at ultrasound, and by the re-establishment of regular menses after estroprogestin discontinuation.

Conclusions

Long-term suppression of the endogenous gonadotropins using estroprogestins may be suggested as a treatment able to restore ovarian responsiveness even in patients with premature ovarian insufficiency showing highly elevated gonadotropin levels.

Premature ovarian insufficiency (POI), is defined as secondary amenorrhea with elevated gonadotropin level observed under the age of 40 and affects 1–2 % of women of the general population [7]. POI is highly heterogeneous condition that may have iatrogenic, autoimmune, infective, chromosomal, genetic or idiopathic origin [4]. Post-pubertal onset of ovarian failure represents the large majority of the cases: this is characterized by secondary amenorrhea associated with premature follicular depletion or arrested folliculogenesis [4].

Although elevation in gonadotropin serum level may suggest an irreversible impairment of ovarian reserve and function, intermittent follicular function and spontaneous ovulation clearly occur in some POI-affected women [20]. Moreover, POI may either spontaneously resolve or may respond to therapeutic modalities such as glucocorticoids or exogenous estrogen administration, thus indicating that ovarian failure is not always permanent. Immunosuppression with glucocorticoids has been employed for up to 12 months in cases of POI of supposed autoimmune etiology [11], however proof of the efficacy of this treatment has not been forthcoming as the two randomized, placebo-controlled trial using corticosteroid and ovulation induction in POI women demonstrated either no ovulation or a low ovulation rate [2, 21]. On the other hand, either short course or long-term (up to 24 months) estrogen administration have been found to be useful in these patients, as this treatment may overcome ovarian FSH receptor desensitization [18].

Here we report the case of a young woman with POI of unknown origin who did not respond to corticosteroid treatment but showed resumption of ovarian function after 4 years of estro-progestin treatment.

Case report

A 20 year old woman was referred to our center in 2003 with a history of 2 years of amenorrhea. The patient started spontaneous menarche at the age of 13 and had regular menses until the age of 18. At that time she first developed symptoms of Crohn’s disease (abdominal pain, weight loss and debilitating fatigue) together with amenorrhea, therefore she was placed on azathioprine treatment with moderate improvement of her disease symptoms, although with episodic recrudescence of the disease. Due to the persistence of amenorrhea, the patient was admitted to an endocrinology clinic in order to undergo basal and dynamic endocrine testing. Basal endocrine testing revealed highly elevated FSH and LH serum levels (255 mIU/ml and 182 mIU/ml respectively) and low estradiol serum level (21 pg/ml), while thyroid and adrenal function was normal, the latter being evaluated by basal and ACTH-stimulated steroids measurement. Endoscopy revealed a mild atrophic gastritis together with pancolitis. Diagnosis of premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) was made, an hormone replacement therapy was prescribed in order to avoid menopausal symptoms, but no hope of future motherhood was given.

The patient did not accept this conclusion and, after having uselessly consulted other specialists, came to our attention.

The physical examination revealed normal secondary sexual characteristics, blood pressure (110/75 mmHg) and body mass index (21 kg/cm2). Pelvic ultrasound showed small ovaries (18 × 11 mm) with a 2 cm simple ovarian cyst in the right gonad, and thin endometrium. Immunological screening revealed undetectable antiovarian and antiadrenal autoantibodies. As agreed to the gastroenterologist, the patient started a treatment with oral prednisone (Deltacortene, Bruno Farmaceutici - Italy), 25 mg daily.

On the second examination (Oct 2003) the patient showed hypertricosis (score Ferriman Gallwey 8) and mild weight gain. Endocrine testing revealed FSH 200 mIU/ml, LH 103 mIU/ml, estradiol 44 pg/ml, while immunological screening revealed undetectable anti-smooth muscle antibodies, anti-mitochondrial antibodies, liver-kidney microsomal antibodies, anti-nuclear antibodies, anti-DNA antibodies and anti- parietal cell antibodies. Pelvic ultrasound showed small ovaries (21 × 11 mm), simple ovarian cyst 2 cm, 6 mm endometrium.

The patient continued the treatment and 3 months later (Jan 2004) returned to our center with a colonoscopy report showing remission of the Crohn’s disease. Pelvic ultrasound showed a follicle of 16 mm in diameter and a simple ovarian cyst 2,5 cm, however progesterone challenge test failed to induce a menstrual bleeding. FSH and LH serum levels were unmodified.

Due to treatment failure, prednisone was suspended, while estro-progestin treatment containing 0,075 mg gestodene plus 0,03 mg ethinyl estradiol (Ginoden, Bayer Italy) was started. The patient was instructed to stop treatment 2 months before undergoing the scheduled blood samples for routine hormonal assay.

Nine months later (Oct 2004) patient’s FSH and LH serum levels dropped to 68 mIU/ml and 38 mIU/ml respectively, while estradiol raised to 42 pg/ml. Inhibin B level was 51 pg/ml. The next two examinations, performed eight (Jun 2005) and 16 months (Feb 2006) later respectively, revealed a further reduction in FSH and LH serum levels (37.4 mIU/ml and 5.5 mIU/ml and 10.7 mIu/ml and 1,1 mIU/ml respectively). Despite this reduction in gonadotropin level, pelvic ultrasound still revealed small ovaries (sin 17 × 11, dx 23 × 11) with simple ovarian cyst of 18 mm in diameter in the right gonad, as well as small uterus.

FSH and LH levels, as well as ovarian volume, remained unchanged in the following 17 months (see Table 1). On February 2008 the patient reported spontaneous menstrual bleeding after 2 months of estro-progestin withdrawn. FSH and LH serum levels were unmodified (14.4 mIU/ml and 3.8 mIU/ml respectively), however pelvic ultrasound showed increased ovarian and uterine volume compared to the previous controls (right ovary 23,5 × 15 mm, left 33,7 × 19 mm, uterus 75,8 × 25,6 × 45,6 mm, endometrial thickness 3 mm) with a follicle of 14,9 mm in diameter in the right ovary and multiple follicles in the left ovary.

Table 1.

An overview of patient’s parameters during the 11 years follow-up period

| Follow-up | FSH (mIU/ml) | LH (mIU/ml) | E2 (pg/ml) | Ultrasound | Clinical picture | Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 255 | 182 | 21 | Not available | Amenorrhea, Crohn’s disease | None |

| Mar 2003 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | Small ovaries, thin endometrium | Amenorrhea, Crohn’s pancolitis | Prednisone 25 mg daily |

| Oct 2003 | 200 | 103 | 32 | Small ovaries , 6 mm endometrium | Amenorrhea, Crohn’s disease | Prednisone 25 mg daily |

| Jan 2004 | 200 | 85 | 32 | Follicle 16 mm | Amenorrhea Crohn’s remission | Prednisone withdrawal. estroprogestins |

| Oct 2004 | 68 | 38 | 42 | Small ovaries | Amenorrhea | Estro-progestins |

| Jun 2005 | 37,4 | 5,5 | >20 | Small ovaries | Amenorrhea | Estro-progestins |

| Feb 2006 | 10.7 | 1.1 | <20 | Small ovaries and uterus | Amenorrhea | Estro-progestins |

| Oct 2006 | 10.8 | 3.5 | 15.3 | Small ovaries | Amenorrhea | Estro-progestins |

| Jun 2007 | 12,3 | 5,4 | 26 | Small ovaries | Amenorrhea | Estro-progestins |

| Feb 2008 | 14.4 | 3.8 | 20 | Normal ovarian and uterine volume, follicle 14 mm | Regular menses after estro-progestins withdrawal | Estro-progestins |

| May 2009 | 11,4 | 5,92 | 29,8 | Normal ovarian and uterine volume, follicle 14 mm | Regular menses after estro-progestins withdrawal | Estro-progestins |

| Oct 2010 | 3 | 5,1 | 45 | Normal ovarian and uterine volume, follicle 14 mm | Regular menses after estro-progestins withdrawal | Estro-progestins |

| Oct 2011 | 8,8 | 6,2 | 45 | Normal ovarian and uterine volume, follicle 15 mm | Regular menses after estro-progestins withdrawal | Estro-progestins |

Starting from this period, routine examination was performed yearly in compliance with patient’s desire. The patient still reported spontaneous menstrual bleeding in the medication-free period. A reduction in FSH and LH level was observed in October 2010, when patient’s FSH serum level was 3 mIU/ml, LH was 5,5 mIU/ml, estradiol was 45 pg/ml. In the same period anti-mullerian hormone (AMH) serum level assay was made available in the local laboratory, resulting in 4,2 ng/ml (normal range 0.14–5,5 ng/ml). Transvaginal ultrasound showed a dominant follicle in the right ovary, 14 mm in diameter. The last examination, performed in October 2011, confirmed the previous findings.

An overview of patient’s parameters during the 11 years follow-up is showed in Table 1; FSH and LH serum levels behavior in response to treatment is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Gonadotropin levels in response to corticosteroid and estro-progestin treatment. Arrows indicate when treatment was started P = Prednisone CE = Estro-progestins

Up till now the patient is still unmarried and isn’t seeking pregnancy, however she is planning to get married and have a baby in the next 2 years.

Discussion

Resumption of ovarian function in women with premature ovarian insufficiency is not a rare event. Overall, POI patients appear to have an approximately 5 to 10 % chance of conceiving after receiving their diagnosis [20]. This resumption may be either spontaneous or as a consequence of a corticosteroid or estrogen treatment.

We are presenting the case of a young women with premature ovarian failure of unknown origin, who did not respond to corticosteroid treatment but obtained the resumption of her ovarian function after 4 years of estro-progestin treatment. To the best of our knowledge the uniqueness of this case pertains to the resumption of the ovarian failure despite the initial very high gonadotropin serum levels, It has been observed, in fact, that POI-affected women with FSH below 50 mIU/ml have a better prognosis in terms of ovarian resumption compared to those with higher levels [5]

The initial high gonadotropin serum levels found in our patient may seem surprising, however the patient’s young age at disease onset may account for this. Indeed, we would not expect to find gonadotropin serum levels comparable to those seen in older menopausal women, due to several reasons. It has been demonstrated that, as aging progresses, gonadotropin levels decrease, as do gonadotropin pulse frequency and amplitude. As a matter of fact, early postmenopausal women (45–55 years) have significantly higher gonadotropin levels compared to late postmenopausal women (70–80 years) [22]. Moreover, there is also evidence that GnRH neurons undergo age-related impairment in terms of biosynthesis, processing, and release of the GnRH decapeptide before reproductive failure, suggesting a contributory role of GnRH cells to reproductive failure itself [23]. Therefore, differently to what happen in older women, our patient GnRH neurons could have produced a powerful and supraphysiological response to the estrogen deprivation as well as to the presumable fall in inhibin B level, similarly to what has been found to happen in ovariectomized mice, where GnRH pulsatility is increased toward saturation after ovariectomy [8].

Also the long-time of estro-progestin treatment required to achieve the resumption of ovarian function contributes to the singularity of this case. Two years of estro-progestin treatment were necessary to bring gonadotropin serum levels in the normal range (Fig. 1), but the ovarian responsiveness, as expressed by normal ovarian volume and by ovulatory follicles at ultrasound, as well as by the re-establishment of regular menses after estro-progestin discontinuation, was achieved after 4 years of treatment. In most reported cases the ovulatory response occurs after 2 to 8 months course of estro-progestin therapy [1, 17], though 2 years of treatment have been found to be necessary in one case [18]. Indeed, follicle-like structures were demonstrated by ultrasound in earlier follow-up visits (see Table 1), but they weren’t likely to demonstrate a functional ovarian activity. As a matter of fact, pelvic ultrasound may show ovarian follicle-like structures in 41 % of POI patients, but these follicles doesn’t appear to function normally, due to poor correlation between their diameter size and estradiol serum level [20].

An explanation for the delayed ovarian response to treatment may be hypothesized. It is presumed that chronically elevated gonadotropins levels result in receptor down-regulation or desensitization. Suppression of the elevated endogenous gonadotropins using estro-progestins have been found to restore ovarian responsiveness in selected patients with POI [10, 14, 24], as estrogens may enhance the stimulatory effect of FSH on granulosa-cell FSH receptors as well as FSH binding to its receptors [19]. The down-regulating effect of estro-progestin treatment on ovarian FSH receptor has been found to be time-dependent and dose-dipendent in mice [16], therefore a prolonged estro-progestin treatment could be necessary in case of severe ovarian receptor down-regulation.

In addition, ovariectomy in rats has been associated with alterations in gonadotroph morphology in terms of hypertrophy that may be reversed by estradiol treatment, particularly in young rats [23]. It could be hypothesized that a long-time estro-progestin treatment was required to induce gonadotroph shrinkage in our patient, as well as to restore her pituitary and hypothalamus sensitivity to sex steroids. It has been demonstrated, indeed, that the activation of pituitary estrogen receptor is able to restore all pituitary reproductive functions in young ovariectomized rats [12].

We are unable to demonstrate the exact etiopathogenesis of POI in our patient. An autoimmune origin of the premature ovarian failure was first suspected, due to the contemporary presentation of amenorrhea and Crohn’s disease symptoms, the latter having been described in association with POI [11]. In light of this hypothesis we decided to start a corticosteroid treatment, however this strategy did not affect FSH, LH, estradiol level as well as ovarian volume and architecture in a 10 months follow-up period. On average, a two-three months period of corticosteroid treatment has been found to be sufficient to resume the ovarian function in selected POI patients (Forges 2; [2, 3, 6]) although in rare cases it had to be prolonged for up to 1 year [9]. A possible role of inactivating FSH receptor mutation in the etiopathogenesis of POI in our patient may be hypothesized, as it has been demonstrated that, similarly to what has been found in our patient, affected women show normal or low normal AMH level [13]; yet, normal AMH levels have been detected also in women with POI due to steroidogenic cell autoimmunity [15].

Our patient is unmarried, however she is planning to get married and have a baby in the next 2 years. We cannot speculate about her fertility potential, however her FSH and AMH level seem permissive for an ovarian stimulation trial.

In conclusion, we have reported a case of a women with POI of unknown origin who had her ovarian function restored after 4 years of estro-progestin treatment following a unsuccessful corticosteroid treatment. We think that this case report may suggest, together with previous demonstrations [18], that estro-progestin treatment might be proven in POI women, even in cases with highly elevated gonadotropin serum levels, before telling them that they are definitely sterile.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest statement and funding

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. This research did not receive any specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sector.

References

- 1.Anasti JN, Kimzey LM, Defensor RA, White B, Nelson LM. A controlled study of danazol for the treatment of karyotypically normal spontaneous premature ovarian failure. Fertil Steril. 1994;62:726–730. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)56996-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Badawy A, Goda H, Ragab A. Induction of ovulation in idiopathic premature ovarian failure: a randomized double-blind trial. Reprod Biomed Online. 2007;15:215–219. doi: 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)60711-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barbarino-Monnier P, Gobert B, Guillet-May F, Bene MC, Barbarino A, Foliguet B, Faure GC. Ovarian autoimmunity and corticotherapy in an in-vitro fertilization attempt. Hum Reprod. 1995;10:2006–2007. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a136225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beck-Peccoz P, Persani L. Premature ovarian failure. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2006;6:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bidet M, Bachelot A, Bissauge E, Golmard JL, Gricourt S, Dulon J, Coussieu C, Badachi Y, Touraine P. Resumption of ovarian function and pregnancies in 358 patients with premature ovarian failure. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:3864–3872. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corenblum B, Rowe T, Taylor PJ. High-dose, short-term glucocorticoids for the treatment of infertility resulting from premature ovarian failure. Fertil Steril. 1993;59:988–991. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)55915-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coulam CB, Adamson SC, Annegers JF. Incidence of premature ovarian failure. Obstet Gynecol. 1986;67:604–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Couse JF, Yates MM, Walker VR, Korach KS. Characterization of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis in Estrogen Receptor (ER) null mice reveals hypergonadism and endocrine sex reversal in females lacking ER but not ER. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:1039–1053. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cowchock FS, McCabe JL, Montgomery BB. Pregnancy after corticosteroid administration in premature ovarian failure (polyglandular endocrinopathy syndrome) Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;158:118–119. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(88)90791-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dragojević-Dikić S, Rakić S, Nikolić B, Popovac S. Hormone replacement therapy and successful pregnancy in a patient with premature ovarian failure. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2009;25:769–772. doi: 10.3109/09513590903004126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forges T, Monnier-Barbarino P, Faure GC, Benè MC. Autoimmunity and antigenic targets in ovarian pathology. Hum Reprod Updat. 2004;10:163–175. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmh014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gordon A, Aguilar R, Garrido-Gracia JC, Guil-Luna S, Sa’nchez-Cespedes R, Millan Y, Mulas JM, Sanchez-Criado JE. Activation of estrogen receptor-a induces gonadotroph progesterone receptor expression and action differently in young and middle-aged ovariectomized rats. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:2618–2628. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kallio S, Aittomaki K, Piltonen T, Veijola R, Liakka A, Vaskivuo TE, Dunkel L, Tapanainen JS. Anti-Mullerian hormone as a predictor of follicular reserve in ovarian insufficiency: special emphasis on FSH-resistant ovaries. Hum Reprod. 2012;27:854–860. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laml T, Huber JC, Albrecht AE, Sintenis WA, Hartmann BW. Unexpected pregnancy during hormone-replacement therapy in a woman with elevated follicle-stimulating hormone levels and amenorrhea. Gynecol Endocrinol. 1999;13:89–92. doi: 10.3109/09513599909167538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marca A, Marzotti S, Brozzetti A, Stabile G, Artenisio AC, Bini V, Giordano R, Bellis A, Volpe A, Falorni A, et al. Primary ovarian insufficiency due to steroidogenic cell autoimmunity is associated with a preserved pool of functioning follicles. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:3816–3823. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lv X, Shi D. Combined effects of levonorgestrel and quinestrol on reproductive hormone levels and receptor expression in females of the Mongolian gerbil (Meriones unguiculatus) Zoolog Sci. 2012;9:37–42. doi: 10.2108/zsj.29.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nelson LM, Kimzey LM, White BJ, Merriam GR. Gonadotropin suppression for the treatment of karyotypically normal spontaneous premature ovarian failure: a controlled trial. Fertil Steril. 1992;57:50–55. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)54775-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neves-e-Castro M. An estrogen treatment may reverse a premature ovarian failure. Fertil Steril. 2009;91:e1. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.12.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tartagni M, Cicinelli E, Pergola G, Salvia MA, Lavopa C, Loverro G. Effects of pretreatment with estrogens on ovarian stimulation with gonadotropins in women with premature ovarian failure: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Fertil Steril. 2007;87:858–861. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.08.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kasteren YM, Schoemaker J. Premature ovarian failure: a systematic review on therapeutic interventions to restore ovarian function and achieve pregnancy. Hum Reprod Update. 1999;5:483–492. doi: 10.1093/humupd/5.5.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kasteren YM, Braat DDM, Hemrika DJ, Lambalk CB, Rekers-Mombarg LTM, Blomberg BME, Schoemaker J. Corticosteroids do not influence responsiveness to gonadotropins in patients with premature ovarian failure: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Fertil Steril. 1999;71:90–95. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(98)00411-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yin W, Gore AC. Neuroendocrine control of reproductive aging: roles of GnRH neurons. Reproduction. 2006;131:403–414. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yin W, Wu D, Noel ML, Gore AC. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuroterminals and their microenvironment in the median eminence: effects of aging and estradiol treatment. Endocrinology. 2009;150:5498–5508. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zargar AH, Salahuddin M, Wani AI, Bashir MI, Masoodi SR, Laway BA. Pregnancy in premature ovarian failure: a possible role of estrogen plus progesterone treatment. J Assoc Phys India. 2000;48:213–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]