Abstract

Oxysterols are well known as physiological ligands of Liver X receptors (LXRs). Oxysterols, 25-Hydroxycholesterol (25HC) and 27-hydroxycholesterol as endogenous ligands of LXRs, suppress cell proliferation via LXRs signaling pathway. Recent reports have shown that sulfated oxysterol, 5-cholesten-3β, 25-diol 3-sulfate (25HC3S) as LXRs antagonist, plays an opposite direction to oxysterols in lipid biosynthesis. The present report was to explore the effect and mechanism of 25HC3S on hepatic proliferation in vivo. Following administration, 25HC3S had a 48 h half life in the circulation and widely distributed in mouse tissues. Profiler™ PCR array and RTqPCR analysis showed that either exogenous or endogenous 25HC3S generated by overexpression of oxysterol sulfotransferase (SULT2B1b) plus administration of 25HC significantly up-regulated the proliferation gene expression of Wt1, Pcna, cMyc, cyclin A, FoxM1b, and CDC25b in a dose-dependent manner in liver while substantially down-regulating the expression of cell cycle arrest gene Chek2 and apoptotic gene Apaf1. Either exogenous or endogenous administration of 25HC3S significantly induced hepatic DNA replication as measured by immunostaining of the PCNA labeling index and was associated with reduction in expression of LXR response genes, such as ABCA1 and SREBP-1c. Synthetic LXR agonist T0901317 effectively blocked 25HC3S-induced hepatic proliferation. Conclusions: 25HC3S may be a potent regulator of hepatocyte proliferation and oxysterol sulfation may represent a novel regulatory pathway in liver proliferation via inactivating LXR signaling.

Keywords: 25-hydroxycholesterol, Cytosolic sulfotransferase 2B1b, Liver X Receptors, oxysterol, oxysterol sulfation, proliferating cell nuclear antigen

1. Introduction

In mammals cholesterol is the archetypical steroid, serves as a structural component of membranes and the precursor of hormonal steroids and bile acids. The major route for cholesterol elimination from the body is by conversion to bile acids, mostly in the liver. Oxysterols which were once thought of as just simple intermediates in the conversion of cholesterol to bile acids, have been shown to be biologically active molecules e.g. as ligands to nuclear receptor [1], as ligands to G protein-coupled recptors [2], as regulators of cholesterol biosynthesis [3,4], and regulate cell proliferation and apoptosis [5,6].

Recently, we found that overexpression of mitochondrial cholesterol delivery protein (steroidogenic acute regulatory protein, StAR) upregulated bile acid synthesis and secretion via the “ acidic ” pathway initiated by cholesterol 27-hydroxylase, and downregulated cholesterol and fatty acid biosynthesis. A search for the possible mechanism of these regulatory effects led to the finding of a novel sulfated oxysterol, 5-cholesten-3 β-25-diol-3-sulfate (25HC3S) [7,8,9]. This sulfated oxysterol is synthesized from sulfation of 25-hydroxycholesterol (25HC) catalized by sterol sulfotransferase 2B1b (SULT2B1b) [10] and appears to play a role in the maintenance of intracellular cholesterol and lipid homestasis. Addition of 25HC3S in human and rat hepatocytes and human acute monocytic leukemia cell line–derived macrophages decreases expression and processing of Liver X receptor (LXR) and its target gene sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c (SREBP-1c), and subsequently decreases intracellular levels of free fatty acids, cholesterol, and triglycerides [11].

LXRs are nuclear receptors that play a crucial role in the control of lipid metabolism[12]. LXRs enhance fatty acid synthesis by activating the transcription of the gene SREBP-1c, which in turn activates lipogenic genes [13,14]. LXRs also directly stimulate the transcription of certain lipogenic genes, including acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC-1) and fatty acid synthase (FAS) [15,16]. Interestingly, recent studies have identified LXRs as anti-proliferative factors in several cellular and animal models [17,18,19,20]. The LXR activation-mediated cell cycle arrest is closely correlated with the lipogenic gene expression and triacylglyceride accumulation [21]. LXR agonists appear to cause G1 cell cycle arrest in prostate and breast cancer cells by reducing cyclin gene expression such as cyclin A2 and cyclin D1 [20,22]. During liver regeneration following partial hepatectomy, the expression of SULT2B1b is significantly increased, while LXR signaling is substantially repressed [17]. These findings suggest that 25HC3S may exert an effect in liver proliferation.

In the present studies, we show for the first time that 25HC3S is able to up-regulate proliferative gene expression and induce DNA replication in the liver. Conversely, administration of the potent LXR synthetic agonist, T0901317, leads to effective repression of 25HC3S-induced proliferation, indicating that the promotion of proliferation by 25HC3S is via LXR signaling. These findings shed light on a previously undescribed function of 25HC3S in liver.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis of 5-cholesten-3beta, 25-diol 3-sulfat (25HC3S)

25HC3S was synthesized as described previously [23]. Briefly, a mixture of 25-hydroxycholesterol (402 mg, 1mmol) and triethylamine-sulfur trioxide pyridine complex (106mg, 1mmol) in 5 ml of dry pyridine was stirred at 25 °C for 2 h. After the solvents were evaporated at reduced pressure, products were purified by HPLC using a silica gel column. Methylene chloride and methanol (5%) were used as the mobile phase. The product was further purified by reverse-phase HPLC using C18 column as a white powder. The structure of the product was characterized by mass spectrum and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy analysis as described previously [23].

2.2. Synthesis of [3H]-25HC3S

A mixture of [3H]-25HC (10 μCi), cholesterol (4 mg) and triethylamine-sulfur trioxide complex (1 mg) in 500 ul of dry pyridine was stirred at 20 °C for 1h. After the solvents were evaporated, 1 ml of alkaline methanol (pH 8) was added, mixed, filtered, and purified by HPLC (mobile phase A is 20% CH3CN in H2O, B is 20% CH3CN in CH3OH. 0-20min, A 50%-0%, B 50%-100%, 2ml/min; 20-35min, A 0%, B 100%, 2ml/min; 35-40min, A 0%-50%, B 100%-50%, 2ml/min). A pure peak with the same retention time as standard 25HC3S and with high radioactivity was collected for further usage.

2.3. Animal maintenance and treatment

Nine- to 12-week-old C57BL/6 mice were used and received humane care in accordance with the institutional guidelines and the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Mice were randomly allocated into the following groups (n=5-6/group): (□) vehicle group-mice were administrated with 10% ethanol in phosphate buffer solution (PBS) intravenously (I.V.); (□) 25HC3S group-same as vehicle group but in which different concentrations of 25HC3S (10% ethanol) was administered I.V.; (□) T0901317 group-identical to vehicle group except the administration of T0901317 (5 mg/kg, 10% ethanol administered I.V.; Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI); (□) 25HC3S + T0901317 group-mice were administrated with 25HC3S and T0901317 (5 mg/kg, 10% ethanol administered I.V.). To get the mouse model with high endogenous 25HC3S, mice were received an I.V. injection of adenovirus encoding human SULT2B1b (Ad-SULT2B1b, 1×108 pfu/mouse), and further supplemented with 25HC (25mg/kg, 10% ethanol; Research Plus, Inc. Bayonne, NJ) intraperitoneally (I.P.), 2 days after the adenovirus infection and followed by once every two days [24]. Adenovirus encoding β-Gal (Ad-Control) and 10% ethanol (vehicle) in PBS was used as control, respectively. Animals were sacrificed at 48 h after administration or day 5 following adenovirus injection. Blood samples were collected at sacrifice and serum was separated, stored at −80 °C until assayed. Alanine aminotrasferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and alkaline phosphatase (AP) concentrations were measured in the clinical lab at the McGuire VA Medical center. Liver tissues were harvested and divided into two portions, one for analysis of gene expression and the other for morphological studies.

2.4. Biodistribution and pharmacokinetic studies

In a separate set of experiments, mice were received an I.V. injection of [3H]-25HC3S (1×106 cpm/mouse) and 25HC3S (5 mg/kg). At 4, 24, 48, and 96 h after the injection, mice were sacrificed, tissues (brain, heart, lung, liver, kidney, spleen, stomach, small intestine, skeletal muscle, and colon) were rapidly dissected and weighed, and the radioactivity was measured using a liquid scintillation counter with automatic decay correction (Beckman Counter, Atlanta, GA). Tissue values were calculated as a percentage of injected counts per gram of tissue (%IC/g). For pharmacokinetics, blood samples (30 μl) were collected at selected times after injection from 0 to 96 h via tail clip. Counts of radioactivity were expressed as IC/ml of blood.

2.5. RNA extraction

Total liver RNA was extracted using SV Total RNA Isolation Kit (Promega, Wisconsin, WI) according to the manufacture’s instruction. RNA purity was checked by spectrophotometer. Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized by retrotranscribing, 2 ug of total RNA with Oligo dT primers and M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

2.6. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RTqPCR) and cell cycle RT2 Profiler™ PCR array

PCR assays were performed in 96-well optical reaction plates using the ABI 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). PCR assays were conducted in triplicate wells for each sample. Baseline values of amplification plots were set automatically and threshold values were kept constant to obtain normalized cycle times and linear regression data. The following reaction mixture per well was used: 2×SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (10 ul), primer at the final concentration of 10 uM (1 ul), Rnase-free water (4 ul), cDNA (5 ul, 10 ng). For all experiments the following PCR conditions were used: denaturation at 950C for 10 minutes, followed by 40 cycles at 950C for 15 seconds, then at 60 0C for 60 seconds. Quantitative normalization of cDNA in each sample was performed using 18S gene as an internal control. Relative quantification was performed using the ΔΔCT method. Validated primers for RTqPCR are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primer pairs used to amplify PCR products.

| Genes | Forward Sequence | Reverse Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| Mouse PCNA | TTTGAGGCACGCCTGATCC | GGAGACGTGAGACGAGTCCAT |

| Mouse CyclinA | CTTTACCCGCAGCAAGAAAAC | ACGTTCACTGGCTTGTCTTCTA |

| Mouse FoxM1b | CTGATTCTCAAAAGACGGAGGC | TTGATAATCTTGATTCCGGCTGG |

| Mouse CDC25b | AAGTGTGACACCCCTGGAAGA | TCTCATGACACAGCGACTTTGA |

| Mouse GAPDH | CATGTTCCAGTATGACTCCACTC | GGCCTCACCCCATTTGATGT |

The real-time PCR array was performed using the Mouse Cell cycle RT2 Profiler™ PCR Array consisting of 84 key genes involved in apoptosis and proliferation as the manufacturer’s instruction (SABiosciences, Frederick, MD). Total mRNA was reverse-transcribed to cDNA as described above. Three of biologically-distinct specimens were pooled to reduce variance. The cDNA was then amplified precisely like real-time PCR in the primers-preloaded PCR plates on the ABI 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System. ΔΔCT values between different stimulated samples were analyzed as the manufacturer’s instruction, which output p-values for fold-regulation change. Only those genes whose expression levels showed a 1.5-fold or greater expression difference between groups were considered significant changes between groups.

2.7. Immunohistochemical study

Liver specimens collected at sacrifice were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 4 um, deparaffinized, and rehydrated. Endogenous peroxidase was inactivated by incubation in 3% hydrogen peroxide in absolute methanol for 30 min. Antigen retrieval was performed by microwaving of the sections in citrate buffer (PH 6.0) for 10 min. Sections were incubated overnight at 40C with the primary monoclonal antibody against proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) (ab29, Abcam, Cambridge, MA). After washing with PBS, immobilized antibodies were detected by the avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex technique (Vectastain@ ABC Kit, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). DAB (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and haematoxylin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was used as the chromogen and nuclear counterstain, respectively. PCNA-positive and PCNA-negative nuclei were counted in five randomly selected fields for each sample, and each group included sections from at least 3 mice. The quantitation of PCNA expression was expressed as the PCNA labeling index.

2.8. Western blot analysis

Cell lysates were prepared from frozen mouse liver tissues. Total proteins, 100 μg, were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, and transferred to PVDF membrane (Millipore, Eschborn, Germany). Specific protein was probed with specific antibodies against PCNA, human SULT2B1b (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), LXRα (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), ATP-binding cassette transporters 1 (ABCA1) (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), and SREBP-1c (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). β-Actin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was used as a loading control. The immunoreactive bands were detected by Fujifilm Medical System (Fujifilm, Stamford, CT) and quantified by Advanced Image Data Analyzer (Aida Inc., Straubenhardt, Germany).

2.9. Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (S.D). Statistical analysis was carried out using Student’s t test for unpaired samples. A value of P<0.05 was defined as statistical significant.

3. Results

3.1. Pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution

3H-Radioactivity in the blood after I.V. injection of [3H]-25HC3S and 25HC3S is shown in Fig. 1A. 3H-Radioactivity in blood reached a maximum level of 7%IC/g at 1 h, decreasing to half the level at 48 h.

Fig. 1. Pharmacokinetics and tissue biodistribution of radioactivity following intravenous injection of [3H]-25HC3S and 25HC3S in mice.

Each point represents one animal.

The tissue distribution of [3H]-25HC3S were measured at 4, 24, 48 and 96 h following the I.V. administration. As shown in Fig. 1B, most organs exhibited the highest level of 3H-radioactivity at 4 h. Radioactivity remained at that level until 24 h, thereafter gradually decreasing with time. No significant difference in the distribution was observed among the spleen, liver, kidney, lung, small intestine, and colon. The radioactivity in these organs was higher than that in heart, muscle, and brain at each time point after the injection. The long half-life and wide tissue distribution indicate no specific receptor(s) for 25HC3S are present in specific tissues, and 25HC3S most likely enters the cells by diffusion.

3.2. 25HC3S up-regulates proliferative gene expression in mouse liver tissues

In order to investigate the effect of 25HC3S on the hepatic proliferation, the 48 h (half-decay period) was chosen to be studied. Mice were treated for 48 h with different concentrations of 25HC3S as indicated in Section 2.3. ALT, AST and AP activities were determined in mouse serum following the administration. No significant different was seen among the four groups (data not shown) following 25HC3S administration. The hepatic mRNA levels of genes related to cell cycle progression, including cMyc, cyclin A, forkhead Box m1b (FoxM1b), and its target gene cell division cycle 25b (CDC25b), which control the cell cycle progression through G1/S and G2/M phases were investigated following the administration [25]. RTqPCR analysis showed that at concentrations of 25HC3S lower than 5 mg/kg, these gene expressions were significantly up-regulated in the liver tissues in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 2). It was noticed that when the concentration of 25HC3S reached 10 mg/kg, all gene (except cMyc) expressions recovered toward normal. The possible mechanism is unknown.

Fig. 2. Expression levels of cell cycle-related genes in response to 25HC3S in mouse liver tissues.

Mice were treated with 25HC3S at different concentrations as indicated in Section 2.3 for 48 h. Relative mRNA levels of FoxM1b (A), CDC25b (B), Cyclin A (C), and C-myc (D) were analyzed by RTqPCR at the end of the treatment. The results are shown as mean ± S.D. (n=3-5/group) *P<0.05 vs. mRNA expression at 0 mg/kg concentration.

3.3. 25HC3S regulates the expression of apoptotic and cell cycle related genes

To elicit the effects of 25HC3S on liver proliferation, a real-time PCR array encompassing 84 genes associated with apoptosis and cell cycle progression was performed. Mice were treated with vehicle or 25HC3S (5 mg/kg) for 48 h, three of biologically-distinct mRNA samples were isolated and pooled to reduce variance, and the real-time array was run for each treatment. Table 2 lists the genes that were up- or down-regulated by 1.5-fold at least compared to vehicle group. Treatment with 25HC3S resulted in 17 genes up-regulated and 8 genes down-regulated. Interestingly, most of the up-regulated genes were positively related to the regulation of cell cycle progression, anti-apoptosis, and cell differentiation. 25HC3S substantially increased the expression of Wt1 (3.9-fold), an oncogene involved in the cell differentiation and viability [26], and Pcna (3.7-fold) encoding PCNA protein serves as a proliferative cell marker [27]; and significantly increased the expression of Ccne2 encoding cyclin E2, an essential regulator for the cell cycle at the late G1 and early S phase, and Ccnb2 encoding cyclin B2, also serves as a proliferation marker and is crucial for the control of cell cycle at the G2/M transition [28], [29]. On the other hand, 25HC3S substantially decreased the expression of Chek2 encoding CHK2, an important protein kinase involved in cell cycle arrest in response to DNA damage [30], by 4.5-fold, and Apaf1 encoding apoptotic peptidase activating factor 1, a cytoplasmic protein that initiates apoptosis [31], by 3-fold. Taken together, these data demonstrate that 25HC3S may enhance liver proliferation by up-regulating proliferative gene expression and down-regulating apoptotic gene expression.

Table 2.

Mouse Profiler™ Gene Expression Array analysis of mouse liver tissues induced by 25HC3S.

| Functional Gene Grouping |

Gene Symbol | Fold change |

Gene Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regulation of Cell cycle and Genes Related to the Cell Cycle |

Ccnb2(NM_007630) | 1.90 | Cyclin B2 |

| Ccne2(NM_009830) | 2.52 | Cyclin E2 | |

| Cdc25a(NM_007658) | 1.53 | Cell division cycle 25 homolog A (S. pombe) | |

| Cdc25c(NM_009860) | 1.56 | Cell division cycle 25 homolog C (S. pombe) | |

| Pcna(NM_011045) | 3.77 | Proliferating cell nuclear antigen | |

| E2f3(NM_010093) | 2.0193 | E2F transcription factor 3 | |

| Esr1(NM_007956) | 2.2535 | Estrogen receptor 1 (alpha) | |

| Mdm2(NM_010786) | 1.6222 | Transformed mouse 3T3 cell double minute 2 | |

| Wt1(NM_144783) | 3.90 | Wilms tumor 1 homolog | |

| Cell Cycle Arrest and Negative Regulation of Cell Cycle |

Cdkn1a(NM_007669) | 3.0411 | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1A (P21) |

| Gadd45a(NM_007836) | −1.59 | Growth arrest and DNA-damage-inducible 45 alpha | |

| Brca1(NM_009764) | −1.87 | Breast cancer 1 | |

| Chek2(NM_016681) | −4.65 | CHK2 checkpoint homolog (S. pombe) | |

| Cell Differentiation | Hif1a(NM_031168) | 1.7576 | Hypoxia inducible factor 1, alpha subunit |

| Myod1(NM_010866) | 1.56 | Myogenic differentiation 1 | |

| Nf1(NM_010897) | 2.10 | Neurofibromatosis 1 | |

| Induction of Apoptosis |

Apaf1(NM_009684) | −3.21 | Apoptotic peptidase activating factor 1 |

| Tnf(NM_013693) | −2.76 | Tumor necrosis factor | |

| Tnfrsf10b(NM_020275) | −2.28 | Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 10b | |

| Prkca(NM_011101) | 2.29 | Protein kinase C, alpha | |

| Anti-apoptosis | Bag1(NM_009736) | 2.0488 | Bcl2-associated athanogene 1 |

| Bnip3(NM_009760) | 2.0112 | BCL2/adenovirus E1B interacting protein 3 | |

| DNA Repair | Atr(NM_019864) | −2.15 | Ataxia telangiectasia and rad3 related |

| Xrcc5(NM_009533) | −1.90 | X-ray repair complementing defective repair in Chinese hamster cells 5 |

|

| Transcription Factors |

Ep300(NM_177821) | 1.8114 | E1A binding protein p300 |

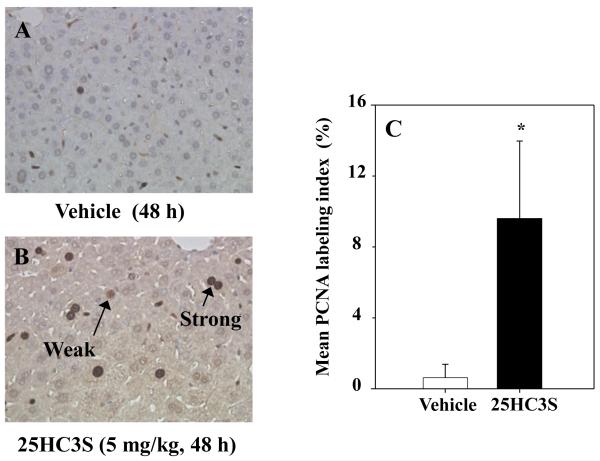

3.4. Exogenous 25HC3S induces DNA replication in mouse liver tissues

Proliferation in liver tissues was assessed by measuring PCNA labeling index (Fig. 3). Treatment of mice with 25HC3S (5mg/kg) for 48 h significantly increased the PCNA labeling index in liver as compared to the vehicle group. There was no significant difference between the vehicle group and no-treatment group (data not shown). The results indicate that 25HC3S promotes mouse liver proliferation.

Fig. 3. Effect of exogenous 25HC3S on PCNA labeling index in mouse liver tissues.

A and B show representative photomicrographs from PCNA-stained liver sections of vehicle (PBS 10% ethanol, 48 h) group (A), and 25HC3S (5 mg/kg, 48 h) group (B). And immunoreaction was observed as strong reaction (short arrow) or weak reaction (long arrow). PCNA labeling index obtained from liver sections of each group was quantitatively analyzed (C). The results are shown as mean ± S.D. (n=3-5/group) *P<0.05 vs. Vehicle.

3.5. Endogenous 25HC3S induces DNA replication in mouse livers

SULT2B1b is responsible for the synthesis of 25HC3S from 25HC via oxysterol sulfation [10]. SULT2B1b overexpression in the presence of 25HC can effectively elevate 25HC3S levels in both primary hepatocytes and mouse liver [32]. To further confirm the proliferation induction by endogenous 25HC3S in liver, PCNA positive cells were compared following overexpression of SULT2B1b. The immunohistochemical analysis showed that overexpression of SULT2B1b resulted in a significant increase in the liver PCNA labeling index at day 5 following the infection (Fig. 4A and 4B). No evidence of toxicity was found (data not shown). The PCNA labeling index was further increased 30% in the livers of mice supplemented with 25HC. These results confirm that 25HC3S promotes liver proliferation.

Fig. 4. Effect of endogenous 25HC3S on PCNA labeling index in mouse liver tissues.

Mice were infected with either Ad-Control or Ad-SULT2B1b (1×108 pfu) in the presence or absence of 25HC (25 mg/kg) as indicated in Section 2.3 for 5 d. PCNA labeling index obtained from liver sections of each group were analyzed at the end of the treatment. The results are shown as mean ± S.D. (n=3-5/group) *P<0.05 vs. corresponding Ad-Control, #P<0.05 vs. Ad-SULT2B1b and vehicle co-treatment.

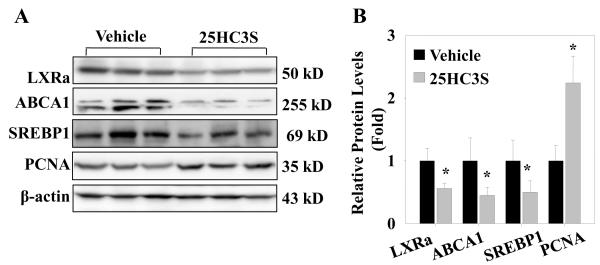

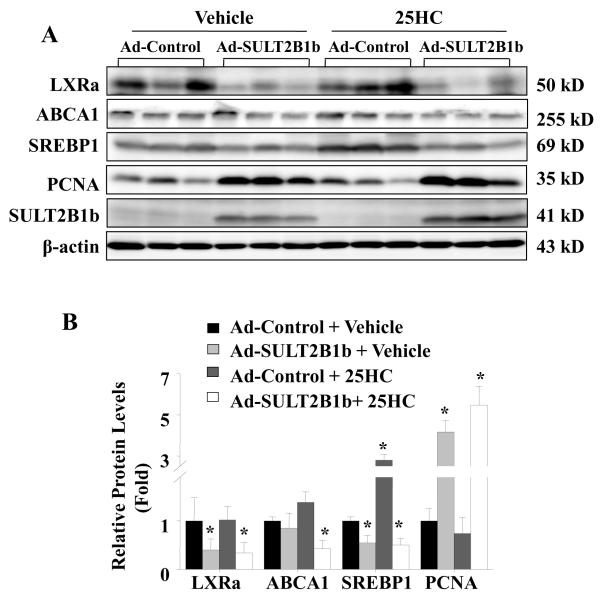

3.6. 25HC3S decreases LXR activity and its target gene expression in the mouse liver tissues

To understand the possible mechanisms by which 25HC3S promotes hepatic proliferation, the expression of genes regulated by LXR signaling pathway was analyzed in mouse liver tissues. As shown in Fig. 5A and 5B, injection of mice with exogenous 25HC3S (5mg/kg, 48 h) inhibited the activity of LXR response in liver, the protein levels of LXRα and its target genes ABCA1 and SREBP-1c decreased by 45%, 55%, and 50%, respectively in the 25HC3S treated group. The exogenous 25HC3S increased PCNA protein level by 2-fold. Similar down-regulated liver LXR signaling and up-regulated PCNA expression were also observed in Ad-SULT2B1b infected mouse, where SULT2B1b overexpression in the presence (or absence) of 25HC decreased the protein levels of LXRa by 70% (60%), ABCA1 by 60% (30%) and SREBP-1c by 50% (50%); and increased the protein level of PCNA by 5-fold (4-fold), as compared to the Ad-control and vehicle co-treatment group (Fig. 6A, B). In the Ad-Control and 25HC co-treatment group, 25HC effectively up-regulated the expressions of SREBP-1c, indicating the activation of LXRs signaling (Fig. 6A, B). The data are not only consistent with previous studies showing the inactivation effect of 25HC3S on LXR responses in primary hepatocytes, but also support the idea that 25HC is a natural LXR ligand in vivo [33]. Considering that LXR activation induces apoptosis and inhibits proliferation in many cells and animal models [17,18,19,20,34], the observations provided support that the stimulation of proliferation by 25HC3S is most likely via the inactivation of LXR signaling.

Fig. 5. Effect of exogenous 25HC3S on LXR activity and its target gene expressions in mouse liver tissues.

Mice were treated with vehicle or 25HC3S (5 mg/kg) as indicated in Section 2.3 for 48 h. LXRα, SREBP-1c, ABCA1, and PCNA proteins were detected by western blot at the end of the treatment (A). Western blot data were quantitatively normalized to ß-actin (B). The results are shown as mean ± S.D. (n=3-5/group) *P <0.05 vs. Vehicle.

Fig. 6. Effect of endogenous 25HC3S on LXR activity and its target gene expressions in mouse liver tissues.

Mice were infected for 5 d with either Ad-Control or Ad-SULT2B1b (1×108 pfu) in the presence or absence of 25HC (25 mg/kg) as indicated in Section 2.3. LXRα, SREBP-1c, ABCA1, and PCNA proteins were detected by western blot at the end of the treatment (A). Western blot data were quantitatively normalized to ß-actin (B). The results are shown as mean ± S.D. (n=3-5/group) *P<0.05 vs. Ad-Control and vehicle co-treatment.

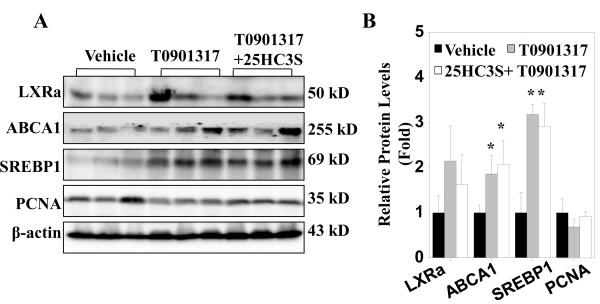

3.7. Synthetic LXR agonist blocks 25HC3S-mediated proliferation in mouse livers

T0901317 is a potent synthetic LXR agonist. As an additional approach to investigate whether LXR signaling repression plays a role in 25HC3S-induced proliferation, we studied the effect of I.V. administration of T0901317 on the 25HC3S-induced proliferation in mice. As shown in western blot analysis in Fig. 7 A and 7B, T0901317 administration induced, at day 2 after the injection, the expressions of LXR target genes ABCA1 and SREBP-1c in both presence and absence of 25HC3S as compared to the vehicle group. Furthermore, the T0901317 administration significantly repressed the 25HC3S-induced PCNA expression. The results further confirm that 25HC3S induces proliferation via inactivation of LXR signaling.

Fig. 7. Effect of LXR activation on 25HC3S-induced proliferation.

Mice were treated with either vehicle or 25HC3S (5 mg/kg) in the presence or absence of T0901317 (5 mg/kg) as indicated in Section 2.3 for 48 h. LXRα, SREBP-1c, ABCA1, and PCNA proteins were detected by western blot at the end of the treatment (A). Western blot data were quantitatively normalized to ß-actin (B). The results are shown as mean ± S.D. (n=3-5/group) *P<0.05 vs. Vehicle.

4. Discussion

25HC3S identified in the hepatocytes nuclei serves as a potent regulator of lipid metabolism and inflammatory responses [9,33]. In 25HC treated human aortic endothelial cells, increases in SULT2B1b expression lead to a substantial increase in 25HC3S levels and a parallel reduction of intracellular lipid levels [35]. The mechanism that accounts for the 25HC3S-induced reduction of lipid levels is via the inhibition of LXR/SREBP1-c signaling [11,35]. Furthermore, 25HC3S has been shown to increase cytoplasmic IκBα levels, to decrease NFκB nuclear translocation, and to play a role in TNFα-induced inflammatory responses [33]. Recently, several reports hint that the 25HC3S is involved in the control of cell growth. These include its ability to increase cell proliferation and decrease apoptosis in THP-1-derived macrophages [11], as well as the increases of SULT2B1b expression in liver after partial hepatectomy [17]. The present study shows that 25HC3S stimulates hepatic proliferation via its effects on LXR signaling in an in vivo model. The results indicate a role of 25HC3S and oxysterol sulfation in the regulation of cell proliferation.

Cell cycle progression is a process regulated by cyclin expression and cyclin-mediated activation of cyclin-dependent kinases (Cdks). In particular, Cyclin A and Cyclin E are important for S-phase entry and progression because the formation of the Cyclin E-Cdk2 and Cyclin A-Cdk2 complexes phosphorylates the retinoblastoma (RB) protein, which subsequently releases bound E2F transcription factor and allows it to stimulate expression of proliferation-specific target genes [28]. Likewise, Cyclin B associates with Cdk1 to mediate cell cycle progression from the G2 phase into mitosis [29]. Furthermore, Cdc25A, Cdc25B, and Cdc25C phosphatase proteins stimulate Cdk activity through dephosphorylation [36,37,38]. In this study, we have shown that 25HC3S increases the mRNA levels of cyclins (Cyclin A, CyclinB, Cyclin E), the E2F3 transcription factor, and Cdc25 by up to 2.5-fold in mouse liver. On the other hand, 25HC3S decreases the mRNA levels of genes involved in the initiation of apoptosis, such as Apaf1, Tnf, and Tnfrsf10b, while increasing the mRNA levels of genes related to anti-apoptosis, including Bag1 and Bnip3 [31,39,40]. More importantly, the percentage of PCNA positive cells is significantly increased in both endogenous and exogenous 25HC3S treated mouse livers. All of these data signify that 25HC3S promotes hepatic proliferation in mice. What, then, is the mechanism by which 25HC3S induce proliferation?

The present study shows that the LXR signaling pathway is down-regulated in the livers of mice treated with 25HC3S (Fig. 5). In fact, this suppressed LXR response following 25HC3S administration has been demonstrated previously in vitro in primary hepatocytes and macrophages [11,33]. In view of recent findings that LXR activation inhibits cellular proliferation, programming cells enter into apoptosis [19,21,34,41], and that down-regulation of the LXR transcriptome provides requisite cholesterol levels for hepatocyte proliferation [17,18], it is reasonable to speculate that LXR inactivation contributes to 25HC3S-induced proliferation. In the current study, we find that in the presence of synthetic LXR agonist, T0901317, 25HC3S fails to induce PCNA expression. Of note is the fact that the magnitude of the induction of LXR activation by T0901317 is greater than that for the inhibition of LXR by 25HC3S [11,35]. On the other hand, recent data suggest that the inhibition of proliferation with LXR agonists in LNCaP cells is mediated via reduced expression of Cyclin A and Cdc25a [21]. Our results are consistent with their data showing opposite changes in Cyclin A and Cdc25a when LXR signaling is inactivated by 25HC3S. Thus, the effect of 25HC3S on proliferation is through inactivation of LXR signaling. It has been reported that 25HC induces apoptosis and the present study, 25HC3S suppress. Therefore, the detail mechanism that oxysterol, oxysterol sulfate, and oxysterol sulfation may play in the apoptosis is worth further investigating.

Cytosolic sulfotransferases (SULTs) sulfate small molecules such as hormones, neurotransmitters, bioamines, and therapeutic drugs [42,43,44]. As an important isoform of SULT2B subfamily, SULT2B1b is expressed in multiple human tissues including placenta, prostate, breast, skin, lung, small intestine, liver and platelets [10,45,46,47,48,49,50]; and functions as a selective cholesterol and oxysterol sulfotransferase [10,35,51,52,53,54]. The effects of endogenous 25HC3S on liver proliferation clearly demonstrate that SULT2B1b overexpression alone increases PCNA-positive cells and PCNA protein levels. This can be explained by two possible mechanisms: generation of oxysterol sulfate, 25HC3S [10], or loss of oxysterols as LXR agonists [20,35,53,55]. Considering the report that overexpression of SULT2B1b inactivates the response of LXRα to oxysterols and inhibits LXR target gene expression [35,55], it is possible that oxysterol reduction may cooperate with the oxsyterol sulfate in switching off the LXR system. Interestingly, oxysterols (e.g. 25HC) are reported to cause apoptosis and induce growth arrest in cells [56], whereas the relative effects of SULT2B1b on proliferation are more pronounced when 25HC is present than absent, supporting the conversion of 25HC to 25HC3S by SULT2B1b [24]; and further confirming the physiological function of 25HC3S in promoting proliferation.

Our data show that the presence of exogenous 25HC3S significantly increases the expression of proliferative genes at the doses lower than 5 mg/kg (Fig. 2). However, this effect is not observed when the concentration reaches to 10 mg/kg. In our preliminary high-performance liquid chromatography studies, we detected a small peak of 25HC in the liver of 25HC3S-treated mice. Thus, it is possible that the reduced effect of 25HC3S on proliferation is related to the accumulation of 25HC.

Previous studies continue to support the intricate checks and balances found within the bile acid biosynthetic pathways. An example is found in the feed forward regulation of LXR by cholesterol. In rodents, LXR is stimulated by surplus cholesterol within the cell, up-regulation within the liver both cholesterol-7a-hydroxylase (CYP7A1) and the Star D1 mitochondrial delivery protein [57,58]. Up-regulation of CYP7A1 leads to increased metabolism and elimination of cholesterol as bile acids [8]. Up-regulation of StarD1 drives the sterol 27-hydroxylase metabolism of cholesterol, generating the regulatory oxysterols discussed in this manuscript. Furthermore, we have found that increased 25HC3S generated by such up-regulation is capable of negative feedback regulation of SULT2B1b [10]. What is being uncovered is a highly regulated pathway of cholesterol metabolism which is capable of regulating intracellular lipid levels along with cell growth and differentiation through the generation of potent regulatory oxysterols. In the absence or inadequate response of this pathway, pathologic levels of lipids accumulate within cells. A clearer understanding of this intracellular lipid regulation could have profound effects on our understanding of NAFLD/NASH and liver regeneration.

Highlights.

Most likely, there is no specific receptor of 25HC3S found in tested tissues in vivo.

Administration of 25HC3S up-regulates proliferative gene expression and down-regulates apoptotic gene expression.

Administration of either exogenous or endogenous 25HC3S induces liver proliferation.

The regulation of liver proliferation by 25HC3S is via LXRs signaling pathway.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dalila Marques, Patricia Bohdan, and Patricia Cooper for providing us with excellent technical help. This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01 HL078898) and the Veterans Administration Department (VA Merit Review).

Abbreviations

- 25HC

25-hydroxycholesterol

- 25HC3S

5-cholesten-3ß, 25-diol 3-sulfate

- ABCA1

ATP-binding cassette transporters A1

- Ad-Control

adenovirus encoding β-Gal

- Ad-SULT2B1b

adenovirus encoding SULT2B1b

- AP

alkaline phosphatase

- ALT

alanine transaminase

- AST

aspartate transaminase

- CDC25

cell division cycle 25

- CDKs

cyclin-dependent kinases

- cDNA

complementary DNA

- CYP7A1

cholesterol-7a-hydroxylase

- FoxM1b

Forkhead Box m1b

- %IC/g

percentage of injected counts per gram of tissue

- I.P.

intraperitonealy

- I.V.

intravenously

- LXR

liver X receptor

- mRNA

messenger RNA

- PCNA

proliferating cell nuclear antigen

- RTqPCR

quantitative real-time PCR

- SREBP-1c

sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c

- StAR

steroidogenic acute regulatory protein

- SULT2B1b

cytosolic sulfotransferase

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors declare that there are no competing financial interests.

References

- [1].Janowski BA, Grogan MJ, Jones SA, Wisely GB, Kliewer SA, Corey EJ, Mangelsdorf DJ. Structural requirements of ligands for the oxysterol liver X receptors LXRalpha and LXRbeta. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:266–271. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.1.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Iguchi Y, Yamaguchi M, Sato H, Kihira K, Nishimaki-Mogami T, Une M. Bile alcohols function as the ligands of membrane-type bile acid-activated G protein-coupled receptor. J Lipid Res. 2010;51:1432–1441. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M004051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Radhakrishnan A, Ikeda Y, Kwon HJ, Brown MS, Goldstein JL. Sterol-regulated transport of SREBPs from endoplasmic reticulum to Golgi: oxysterols block transport by binding to Insig. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:6511–6518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700899104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Brown MS, Goldstein JL. Cholesterol feedback: from Schoenheimer’s bottle to Scap’s MELADL. J Lipid Res. 2009;50(Suppl):S15–27. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800054-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].O’Callaghan YC, Woods JA, O’Brien NM. Oxysterol-induced cell death in U937 and HepG2 cells at reduced and normal serum concentrations. Eur J Nutr. 1999;38:255–262. doi: 10.1007/s003940050075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Corsini A, Verri D, Raiteri M, Quarato P, Paoletti R, Fumagalli R. Effects of 26-aminocholesterol, 27-hydroxycholesterol, and 25-hydroxycholesterol on proliferation and cholesterol homeostasis in arterial myocytes. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1995;15:420–428. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.15.3.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Pandak WM, Ren S, Marques D, Hall E, Redford K, Mallonee D, Bohdan P, Heuman D, Gil G, Hylemon P. Transport of cholesterol into mitochondria is rate-limiting for bile acid synthesis via the alternative pathway in primary rat hepatocytes. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:48158–48164. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205244200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ren S, Hylemon PB, Marques D, Gurley E, Bodhan P, Hall E, Redford K, Gil G, Pandak WM. Overexpression of cholesterol transporter StAR increases in vivo rates of bile acid synthesis in the rat and mouse. Hepatology. 2004;40:910–917. doi: 10.1002/hep.20382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ren S, Hylemon P, Zhang ZP, Rodriguez-Agudo D, Marques D, Li X, Zhou H, Gil G, Pandak WM. Identification of a novel sulfonated oxysterol, 5-cholesten-3beta,25-diol 3-sulfonate, in hepatocyte nuclei and mitochondria. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:1081–1090. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600019-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Li X, Pandak WM, Erickson SK, Ma Y, Yin L, Hylemon P, Ren S. Biosynthesis of the regulatory oxysterol, 5-cholesten-3beta,25-diol 3-sulfate, in hepatocytes. J Lipid Res. 2007;48:2587–2596. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700301-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Ma Y, Xu L, Rodriguez-Agudo D, Li X, Heuman DM, Hylemon PB, Pandak WM, Ren S. 25-Hydroxycholesterol-3-sulfate regulates macrophage lipid metabolism via the LXR/SREBP-1 signaling pathway. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;295:E1369–1379. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90555.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Nomiyama T, Bruemmer D. Liver X receptors as therapeutic targets in metabolism and atherosclerosis. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2008;10:88–95. doi: 10.1007/s11883-008-0013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Chen G, Liang G, Ou J, Goldstein JL, Brown MS. Central role for liver X receptor in insulin-mediated activation of Srebp-1c transcription and stimulation of fatty acid synthesis in liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:11245–11250. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404297101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Liang G, Yang J, Horton JD, Hammer RE, Goldstein JL, Brown MS. Diminished hepatic response to fasting/refeeding and liver X receptor agonists in mice with selective deficiency of sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:9520–9528. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111421200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Joseph SB, Laffitte BA, Patel PH, Watson MA, Matsukuma KE, Walczak R, Collins JL, Osborne TF, Tontonoz P. Direct and indirect mechanisms for regulation of fatty acid synthase gene expression by liver X receptors. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:11019–11025. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111041200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Talukdar S, Hillgartner FB. The mechanism mediating the activation of acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase-alpha gene transcription by the liver X receptor agonist T0-901317. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:2451–2461. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600276-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Lo Sasso G, Celli N, Caboni M, Murzilli S, Salvatore L, Morgano A, Vacca M, Pagliani T, Parini P, Moschetta A. Down-regulation of the LXR transcriptome provides the requisite cholesterol levels to proliferating hepatocytes. Hepatology. 2010;51:1334–1344. doi: 10.1002/hep.23436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Bensinger SJ, Bradley MN, Joseph SB, Zelcer N, Janssen EM, Hausner MA, Shih R, Parks JS, Edwards PA, Jamieson BD, Tontonoz P. LXR signaling couples sterol metabolism to proliferation in the acquired immune response. Cell. 2008;134:97–111. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Blaschke F, Leppanen O, Takata Y, Caglayan E, Liu J, Fishbein MC, Kappert K, Nakayama KI, Collins AR, Fleck E, Hsueh WA, Law RE, Bruemmer D. Liver X receptor agonists suppress vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and inhibit neointima formation in balloon-injured rat carotid arteries. Circ Res. 2004;95:e110–123. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000150368.56660.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Vedin LL, Lewandowski SA, Parini P, Gustafsson JA, Steffensen KR. The oxysterol receptor LXR inhibits proliferation of human breast cancer cells. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:575–579. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Kim KH, Lee GY, Kim JI, Ham M, Lee J. Won, Kim JB. Inhibitory effect of LXR activation on cell proliferation and cell cycle progression through lipogenic activity. J Lipid Res. 2010;51:3425–3433. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M007989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Fukuchi J, Kokontis JM, Hiipakka RA, Chuu CP, Liao S. Antiproliferative effect of liver X receptor agonists on LNCaP human prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7686–7689. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Ren S, Li X, Rodriguez-Agudo D, Gil G, Hylemon P, Pandak WM. Sulfated oxysterol, 25HC3S, is a potent regulator of lipid metabolism in human hepatocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;360:802–808. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.06.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Bai Q, Zhang X, Xu L, Kakiyama G, Heuman D, Sanyal A, Pandak WM, Yin L, Xie W, Ren S. Oxysterol sulfation by cytosolic sulfotransferase suppresses liver X receptor/sterol regulatory element binding protein-1c signaling pathway and reduces serum and hepatic lipids in mouse models of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Metabolism. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2011.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Wang X, Krupczak-Hollis K, Tan Y, Dennewitz MB, Adami GR, Costa RH. Increased hepatic Forkhead Box M1B (FoxM1B) levels in old-aged mice stimulated liver regeneration through diminished p27Kip1 protein levels and increased Cdc25B expression. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:44310–44316. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207510200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Huff V. Wilms’ tumours: about tumour suppressor genes, an oncogene and a chameleon gene. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:111–121. doi: 10.1038/nrc3002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Kelman Z. PCNA: structure, functions and interactions. Oncogene. 1997;14:629–640. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1200886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Harbour JW, Dean DC. The Rb/E2F pathway: expanding roles and emerging paradigms. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2393–2409. doi: 10.1101/gad.813200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Zachariae W, Nasmyth K. Whose end is destruction: cell division and the anaphase-promoting complex. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2039–2058. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.16.2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Matsuoka S, Huang M, Elledge SJ. Linkage of ATM to cell cycle regulation by the Chk2 protein kinase. Science. 1998;282:1893–1897. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5395.1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Cain K. Chemical-induced apoptosis: formation of the Apaf-1 apoptosome. Drug Metab Rev. 2003;35:337–363. doi: 10.1081/dmr-120026497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Li X, Hylemon P, Pandak WM, Ren S. Enzyme activity assay for cholesterol 27-hydroxylase in mitochondria. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:1507–1512. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600117-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Xu L, Bai Q, Rodriguez-Agudo D, Hylemon PB, Heuman DM, Pandak WM, Ren S. Regulation of hepatocyte lipid metabolism and inflammatory response by 25-hydroxycholesterol and 25-hydroxycholesterol-3-sulfate. Lipids. 2010;45:821–832. doi: 10.1007/s11745-010-3451-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Mehrotra A, Kaul D, Joshi K. LXR-alpha selectively reprogrammes cancer cells to enter into apoptosis. Mol Cell Biochem. 2011;349:41–55. doi: 10.1007/s11010-010-0659-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Bai Q, Xu L, Kakiyama G, Runge-Morris MA, Hylemon PB, Yin L, Pandak WM, Ren S. Sulfation of 25-hydroxycholesterol by SULT2B1b decreases cellular lipids via the LXR/SREBP-1c signaling pathway in human aortic endothelial cells. Atherosclerosis. 2011;214:350–356. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Nilsson I, Hoffmann I. Cell cycle regulation by the Cdc25 phosphatase family. Prog Cell Cycle Res. 2000;4:107–114. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-4253-7_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Sebastian B, Kakizuka A, Hunter T. Cdc25M2 activation of cyclin-dependent kinases by dephosphorylation of threonine-14 and tyrosine-15. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:3521–3524. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Trembley JH, Ebbert JO, Kren BT, Steer CJ. Differential regulation of cyclin B1 RNA and protein expression during hepatocyte growth in vivo. Cell Growth Differ. 1996;7:903–916. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Sohn VR, Giros A, Xicola RM, Fluvia L, Grzybowski M, Anguera A, Llor X. Stool-fermented Plantago ovata husk induces apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells independently of molecular phenotype. Br J Nutr. 2011:1–12. doi: 10.1017/S0007114511004910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Petry IB, Fieber E, Schmidt M, Gehrmann M, Gebhard S, Hermes M, Schormann W, Selinski S, Freis E, Schwender H, Brulport M, Ickstadt K, Rahnenfuhrer J, Maccoux L, West J, Kolbl H, Schuler M, Hengstler JG. ERBB2 induces an antiapoptotic expression pattern of Bcl-2 family members in node-negative breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:451–460. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Vedin I, Cederholm T, Freund-Levi Y, Basun H, Hjorth E, Irving GF, Eriksdotter-Jonhagen M, Schultzberg M, Wahlund LO, Palmblad J. Reduced prostaglandin F2 alpha release from blood mononuclear leukocytes after oral supplementation of omega3 fatty acids: the OmegAD study. J Lipid Res. 2010;51:1179–1185. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M002667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Coughtrie MW, Sharp S, Maxwell K, Innes NP. Biology and function of the reversible sulfation pathway catalysed by human sulfotransferases and sulfatases. Chem Biol Interact. 1998;109:3–27. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(97)00117-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Falany CN. Enzymology of human cytosolic sulfotransferases. FASEB J. 1997;11:206–216. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.11.4.9068609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Strott CA. Sulfonation and molecular action. Endocr Rev. 2002;23:703–732. doi: 10.1210/er.2001-0040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Falany CN, He D, Dumas N, Frost AR, Falany JL. Human cytosolic sulfotransferase 2B1: isoform expression, tissue specificity and subcellular localization. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2006;102:214–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].He D, Frost AR, Falany CN. Identification and immunohistochemical localization of Sulfotransferase 2B1b (SULT2B1b) in human lung. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1724:119–126. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2005.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].He D, Meloche CA, Dumas NA, Frost AR, Falany CN. Different subcellular localization of sulphotransferase 2B1b in human placenta and prostate. Biochem J. 2004;379:533–540. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Higashi Y, Fuda H, Yanai H, Lee Y, Fukushige T, Kanzaki T, Strott CA. Expression of cholesterol sulfotransferase (SULT2B1b) in human skin and primary cultures of human epidermal keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;122:1207–1213. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.22416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Meinl W, Ebert B, Glatt H, Lampen A. Sulfotransferase forms expressed in human intestinal Caco-2 and TC7 cells at varying stages of differentiation and role in benzo[a]pyrene metabolism. Drug Metab Dispos. 2008;36:276–283. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.018036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Yanai H, Javitt NB, Higashi Y, Fuda H, Strott CA. Expression of cholesterol sulfotransferase (SULT2B1b) in human platelets. Circulation. 2004;109:92–96. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000108925.95658.8D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Fuda H, Lee YC, Shimizu C, Javitt NB, Strott CA. Mutational analysis of human hydroxysteroid sulfotransferase SULT2B1 isoforms reveals that exon 1B of the SULT2B1 gene produces cholesterol sulfotransferase, whereas exon 1A yields pregnenolone sulfotransferase. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:36161–36166. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207165200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Meloche CA, Falany CN. Expression and characterization of the human 3 beta-hydroxysteroid sulfotransferases (SULT2B1a and SULT2B1b) J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2001;77:261–269. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(01)00064-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Fuda H, Javitt NB, Mitamura K, Ikegawa S, Strott CA. Oxysterols are substrates for cholesterol sulfotransferase. J Lipid Res. 2007;48:1343–1352. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700018-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Cook IT, Duniec-Dmuchowski Z, Kocarek TA, Runge-Morris M, Falany CN. 24-hydroxycholesterol sulfation by human cytosolic sulfotransferases: formation of monosulfates and disulfates, molecular modeling, sulfatase sensitivity, and inhibition of liver x receptor activation. Drug Metab Dispos. 2009;37:2069–2078. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.025759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Chen W, Chen G, Head DL, Mangelsdorf DJ, Russell DW. Enzymatic reduction of oxysterols impairs LXR signaling in cultured cells and the livers of mice. Cell Metab. 2007;5:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Trousson A, Bernard S, Petit PX, Liere P, Pianos A, El Hadri K, Lobaccaro JM, Ghandour MS, Raymondjean M, Schumacher M, Massaad C. 25-hydroxycholesterol provokes oligodendrocyte cell line apoptosis and stimulates the secreted phospholipase A2 type IIA via LXR beta and PXR. J Neurochem. 2009;109:945–958. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Gupta S, Pandak WM, Hylemon PB. LXR alpha is the dominant regulator of CYP7A1 transcription. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;293:338–343. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00229-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Ning Y, Chen S, Li X, Ma Y, Zhao F, Yin L. Cholesterol, LDL, and 25-hydroxycholesterol regulate expression of the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein in microvascular endothelial cell line (bEnd.3) Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;342:1249–1256. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.02.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]