Abstract

Introduction

Antidepressant medications are widely used by patients requiring spinal surgery. In spite of a generally favorable safety profile of newer antidepressants, several prior studies have suggested an association between use of serotonergic antidepressants and excessive bleeding. This study was designed to determine if there was any association between antidepressant use and the risk of excessive intraoperative blood loss during spinal surgery, and whether particular types of antidepressants were specifically associated with this increased blood loss.

Materials and methods

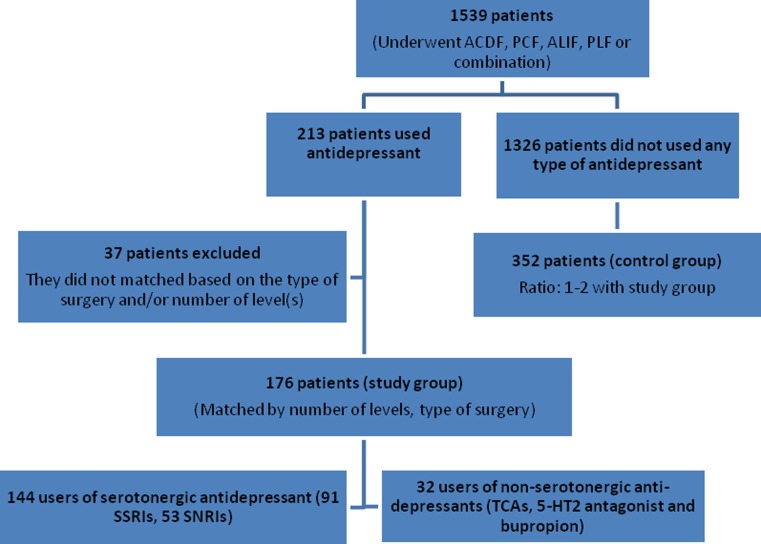

A retrospective case control study was conducted utilizing a population of 1,539 patients who underwent elective spinal fusion by a single surgeon at one medical center. Of the included patients, 213 used antidepressant medication and 1,326 patients did not use any type of antidepressant medication. Of patients taking antidepressants, 37 patients were excluded based on exclusion criteria, leaving 176 patients suitable for inclusion. The study group (176 patients) consisted of all patients who used an antidepressant medication for at least a 2-week period prior to spinal surgery. A control group of 352 patients were assembled from a random sample of 1,326 patients operated on by the same surgeon during the same time period in a two-to-one ratio with study group. Intraoperative blood loss was the primary outcome variable and was compared between the study and control group and between individuals in the study group taking serotonergic (SSRIs or SNRIs) or non-serotonergic antidepressants. Other variables, including length of hospital stay and surgical category, were also collected and analyzed separately.

Results

Overall, the mean blood loss (BL) for the antidepressant group was 298 cc, 23% more than the 241 cc lost by the procedure- and level-matched control group (p = 0.01). Patients taking serotonergic antidepressants also had statistically significant higher blood loss than the matched control group as a whole (334 vs. 241 cc, p = 0.015). This difference was also found in subgroups of patients who underwent anterior cervical discectomy and fusion, lumbar instrumented fusion, or anterior/posterior lumbar fusion. Blood loss was also higher in the subgroup of patients taking bupropion (708 cc, p = 0.023) compared with the control group. The mean length of hospital stay was 33.3% greater in patients on antidepressant medications compared to patients not taking an antidepressant (mean of 4 vs. 3 days, respectively, p = 0.0001). Antidepressant medications may be associated with increased intraoperative blood loss during spinal surgery, although the magnitude of the increased blood loss may not be clinically significant in all cases. The increase was greatest in patients undergoing anterior/posterior lumbar fusions, in whom the intraoperative blood loss was 2.5 times greater than that in the matched control group.

Conclusion

Clinicians treating patients who are planning to undergo elective spinal surgery and are on an antidepressant medication should be aware of this potential effect and should consider tapering off the serotonergic antidepressant prior to surgery.

Keywords: Intraoperative blood loss, Antidepressant, Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), Serotonergic norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), Spinal surgery

Introduction

Antidepressant medications are commonly used for many psychiatric illnesses including major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, panic disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, bulimia nervosa, posttraumatic stress disorder, premenstrual dysphoric disorder, borderline personality disorder, and nicotine dependence [1]. Additionally, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have been used frequently in treating depressive episodes in patients with ischemic heart disease (IHD) and may provide a non-psychiatric protective effect in these patients [2].

Antidepressant medications currently available in the USA include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs including citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, and sertraline), serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs including venlafaxine, duloxetine, and milnacipran, though the last is only FDA approved for the treatment of fibromyalgia), tricyclic and tetracyclic antidepressant, MAO inhibitors, 5-HT2 antagonists, and others. Antidepressant medications can be divided into two groups based on their affinity for the serotonin reuptake transporter. Examples of agents with a higher affinity for the serotonin reuptake transporter included SSRIs, SNRIs, and some tricyclic/tetracyclic antidepressants (e.g., clomipramine). Those with lower or no serotonin affinity include most importantly bupropion, as well as doxepin, nortriptyline, etc. [3].

In spite of the encouraging safety profile of SSRIs, there have been several studies suggesting that SSRIs may cause bleeding abnormalities in orthopedic procedures, mostly following hip and knee arthroplasty [3, 4]. A possible mechanism for this effect involves the inhibition of serotonin reuptake into platelets, as serotonin weakly potentiates platelet aggregation and hemostasis [5]. Paroxetine, for example, decreases cellular serotonin levels by about 80%, resulting in impaired platelet aggregation [6]. Another potential mechanism whereby SSRIs may increase bleeding is through inhibition of cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes such as CYP 1A2, 2D6, 3A4, and 2C9 by fluoxetine, paroxetine and fluvoxamine, which may alter the metabolism of other drugs such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), anticoagulants, and antiplatelet medications, increasing the blood levels of these medications. For instance, CYP 2C9 enzyme is inhibited only with fluvoxamine, the enzyme that metabolizes most NSAIDs. The concomitant use of these two medication classes potentiates the risk of bleeding [5].

Objective

The current study was designed to test the hypothesis that anti-depressant medications and more specifically, serotonin uptake inhibitors (SSRIs or SNRIs) will increase bleeding at the time of elective spinal surgery compared to patients not on any antidepressant.

Methods

Study design

Following institutional review board approval, a retrospective case control cohort study of 1,539 patients was conducted involving patients undergoing surgery at a large teaching hospital. The study group consisted of 213 patients, who underwent elective spinal surgery while taking an antidepressant medication.

The control patient pool consisted of all patients who underwent spinal surgery during the same time period, but did not take antidepressants. From this pool, patients were selected for inclusion in the control study group based on a matching procedure. First, the control pool was sorted by procedure and number of levels. Next, each patient in the study group was matched with two procedure- and level-matched patients selected at random from the pool of patients who underwent the same elective spine surgery by the same surgeon, during the same time period. Thirty-seven patients were excluded from the study because they could not be matched with the control group based on either the type of surgery they underwent or the number of operative levels. The final number of study group was 176 patients after exclusion. All patients were operated on by a single surgeon (TJA) during the period of September 2000 through August 2010.

Inclusion criteria for the study group:

Taking an antidepressant medication for at least the 2-week period before the surgical procedure and still taking it on the day of admission.

Exclusion criteria for patients in the study and control groups:

Less than 18 years old

Incomplete medical records

Any diagnosis of a blood dyscrasia

Inability to match patients taking antidepressants with control patients due to a surgical procedure or number of treated levels for which an insufficient number of control patients with similar procedure were available

Taking a potentially confounding medication in the 10 days prior to their surgery, which included: calcium channel blocker, corticosteroids, an NSAID, iron, methotrexate, a vitamin K antagonist (e.g., warfarin), or an antiplatelet medication (e.g., clopidogrel).

In the control group, 352 patients were selected who were matched to the study group in a two-to-one ratio according to the type of procedure and levels treated, but who were not taking any type of antidepressant medication. Of those 352 patients, 203 (57.6%) were female and 149 (42.4%) were male.

Variables

Intraoperative blood loss for each surgical procedure as determined from the anesthesia record was a primary outcome. At the Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, the blood loss (as recorded in the anesthesia record) is determined by a dedicated perfusionist who directly determines the sum of the volume lost to suction and blood containing surgical sponges, minus the volume of irrigation used for the procedure. Other variables such as the type of surgery, number of levels, length of hospitalization, and acute postoperative complications were recorded for each patient in both the study and control groups. Acute postoperative complications were characterized into minor (transient conditions which resolved without major intervention) and major (more serious conditions which either required reoperation for surgical complications, or were associated with significant risk of mortality or serious morbidity for medical complications). The spinal surgeries performed were subcategorized into the following six categories: anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF), posterior cervical fusion (PCF), combined anterior–posterior cervical fusion (APCF), anterior lumbar interbody fusion (ALIF), and posterior lumbar fusion (PLF) or combined anterior–posterior lumbar fusion (APLF). Antidepressants used by patients in the study group were recorded and then each antidepressant was categorized a priori based on its mechanism of action.

Anesthesia technique

The anesthesia technique has been standardized for the spine service for the past 10 years. Induction of normotensive, balanced general anesthesia is achieved with intravenous narcotic analgesics, muscle relaxants and sedatives, followed by inhalational agents. Muscle relaxants are allowed to wear off following induction and spine exposure to facilitate the use of EMG monitoring. Somatosensory-evoked potentials are monitored in all cases, while motor-evoked potentials are monitored in cases where surgery involves the spinal cord levels. Stimulus-evoked EMG monitoring is used to test the integrity of pedicle screws placed in the lower thoracic or lumbar spine.

A cell salvage suction apparatus is utilized during surgery, and blood loss in excess of 200 cc is returned to the patient during the operative procedure. Postoperatively, closed suction drains are utilized for all cases. The drains are continued until the output falls to less than 30 cc per 8 h shift.

The majority of surgeries (90%) were performed in the years 2005–2009. During this time period, the percentage of surgeries performed each year included in the experimental group averaged 27% and was statistically similar from year to year (p = 0.26), mitigating any potential effect of variation in anesthesia technique or other time-based confounding variable on the difference in EBL between the experimental and control groups.

Statistical methods

Demographic variables were compared using the Chi-square test. The blood loss and length of stay were compared between the study and control groups using the Student’s t test. A step-down multivariable linear regression analysis was used to determine the combined effects of age, gender, number of levels treated, and effect of antidepressant usage. The primary analysis compared patients in the study group who were on any antidepressant medication to patients in the control group who were not on an antidepressant medication. Secondarily, patients on an SSRI or SNRI were combined together due to the common effect of these medications on serotonin reuptake and were compared to patients on other antidepressant medications.

Results

During the study period, a total of 1,539 patients underwent elective spinal fusion by an identified single surgeon (TJA). Of those, 213 patients (13.7%) were taking at least one antidepressant medication for at least a 2-week period prior to their surgery, including the day of admission. Of these 213 patients, 176 (11.4%) met the inclusion and exclusion criteria and were included in the study group. The study group included 128 females (72.7%) and 48 males (27.3%). The control group of 352, including 203 females (57.6%) and 149 males (42.4%), matched for type of surgery and number of levels was assembled from the same patient pool in a two-to-one ratio with study cases. Therefore, the data from 565 patients were included in the analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Patient flowchart for the patients who underwent spinal fusion

When broken down by the type of surgery, 273 patients underwent ACDF, 9 patients underwent combined APCF, 75 patients had PCF, 12 patients had stand-alone ALIF, 15 patients had combined APLF and 144 patients were treated with PLF (Table 1). Of the 176 patients taking antidepressants, 144 took SSRI/SNRI medications (82%), 13 took TCAs (7.5%), 9 took 5-HT2 antagonists (5.2%), and 26 took bupropion (14.4%). Some patients were taking combinations of medications including seven patients using an SSRI/SNRI and bupropion (4%), six using an SSRI/SNRI and 5-HT2 antagonist (3.5%), and three using an SSRI/SNRI and a TCA (1.7%) (Table 2). Ten patients took a TCA only, three patients used 5-HT2 antagonist alone, and 19 patients used bupropion alone (Table 3).

Table 1.

Breakdown of patients by procedure and antidepressant use

| Procedure | Antidepressants (study group) | Matched controls (ratio: 1–2 with study group) |

|---|---|---|

| Anterior discectomy and fusion | 91 | 182 |

| Anterior/posterior cervical fusion | 3 | 6 |

| Posterior cervical fusion | 25 | 50 |

| Anterior lumbar Fusion | 4 | 8 |

| Anterior/posterior lumbar fusion | 5 | 10 |

| Posterior lumbar fusion | 48 | 96 |

| Total | 176 | 352 |

Table 2.

Number of patients who used SSRIs and SNRIs, along with half-life of each drug

| Half-life (h) | # patients (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| SSRIs | 91 (52%) | |

| Sertraline | 26 | 24 (14%) |

| Paroxetine | 21 | 21 (12%) |

| Fluoxetine | 192 | 18 (10%) |

| Escitalopram | 26 | 14 (8%) |

| Citalopram | 35 | 14 (8%) |

| SNRIs | 53 (30%) | |

| Venlafaxine | 11 | 21 (12%) |

| Duloxetine | 12 | 32 (18%) |

| Total | 144 (82%) |

Table 3.

Breakdown of patients who used TCAs, 5-HT2 antagonist and other antidepressant medication

| Antidepressant agents | Used alone | Used along with SSRIs/SNRIs | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| TCAs | 10 (5.6%) | 3 | 13 |

| Amitriptyline | 5 | 1 | 6 |

| Desipramine | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Doxepin | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Nortriptyline | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| 5-HT2 antagonist | 3 (1.7%) | 6 | 9 |

| Trazodone | 3 | 6 | 9 |

| Other | 19 (10.7%) | 7 | 26 |

| Bupropion | 19 | 7 | 26 |

The study and control group had similar mean ages (57.4 and 55.5 years, respectively (p = 0.16). However, there were a significantly higher proportion of females in the study group (74 vs. 49%) (p < 0.001). Fifty patients in the antidepressant group used NSAIDs preoperatively (28.9%) compared with 91 patients in the control group (26.3%, p = 0.53), although all patients had been instructed to stop the usage of these medications at least 10 days prior to their elective surgery.

Blood loss comparisons

A summary of the blood loss data is shown in (Table 4) and (Fig. 2).

Table 4.

Blood loss (BL) (ml) by surgery, use of antidepressants and SSRIs

| Surgery | Control BL | Antidepressant BL | p value | SSRIs/SNRIs BL | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Patients | 241.3 | 298.3 | 0.011 | 334.9 | 0.0001 |

| ACDF | 117.3 | 141.2 | 0.002 | 142.4 | 0.0009 |

| PCF | 239.6 | 262.5 | 0.31 | 259.1 | 0.19 |

| APLF | 535.0 | 960.0 | 0.136 | 1366.7 | 0.01 |

| PLF | 457.1 | 559.6 | 0.033 | 531.6 | 0.14 |

Anterior/posterior cervical fusion and anterior lumbar fusion omitted because there were ≤5 patients on antidepressants in these categories

BL blood loss, SSRIs selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, SNRIs serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, ACDF anterior cervical discectomy fusion, PCF posterior cervical fusion, APLF antero/posterior lumbar fusion, PLF posterior lumbar fusion

Fig. 2.

Blood loss (BL) by surgery in antidepressant users. SSRIs/SNRIs users and control group

Overall, the mean blood loss for the study group was 23% greater than the control group (298 vs. 241 cc, p = 0.01). When evaluated by antidepressant category, it was found that patients taking SSRI/SNRI medications lost significantly more blood compared to the control group (334 vs. 241 cc, p = 0.015).

When evaluated by the type of surgery, patients who underwent ACDF had significantly higher blood loss in the study group compared to the control group (141 vs. 117 cc, p = 0.002) (Fig. 3). When evaluated by antidepressant category, it was found that patients taking SSRI/SNRI medications and those taking bupropion both had a significantly higher blood loss following ACDF (142 cc, p = 0.0009 and 147 cc, p = 0.04, respectively) compared to the control group (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of estimated blood loss in two different setting based on type of arthrodesis

There were no statistically significant differences found between patients taking antidepressants and control patients for the APCF, PCF or ALIF, although there were small numbers of patients in the APCF and ALIF groups. In the combined APLF, study patients had a statistically higher blood loss (960 vs. 535 cc, p = 0.13) when compared with controls. The subgroup of patients who took SSRIs/SNRIs, also demonstrated a statistically greater blood loss (1,367 vs. 535 cc, p = 0.01) in comparison to the controls (Fig. 3) Patients who underwent PLF while taking antidepressants also had significantly higher EBL compared to control patients (560 vs. 457 cc, respectively, p = 0.032). The blood loss for PLF was also found to be statistically higher in the subgroup of patients taking bupropion (708 vs. 457 cc, p = 0.023) compared to controls.

Length of stay comparisons

The mean length of stay in the hospital was significantly greater in the study group compared to the control group (mean of 4 vs. 3 days, respectively, p = 0.0001). When analyzed by procedural categories, there was a trend toward longer stays for patients taking antidepressants when compared with controls in the ACDF group (1.72 vs. 1.45 days, respectively, p = 0.11), PCF (5.8 vs. 3.6 days, respectively, p = 0.057), and APLF (5.6 vs. 4.5 days, respectively, p = 0.16). Patients taking antidepressants who underwent PLF demonstrated a significantly greater length of stay compared to controls (4.8 vs. 4.0 days, p = 0.0004).

Complications

Patients in the study group had eight minor (4.5%) and four major (2.3%) acute complications. Major complications included two patients with wound infections, one with aspiration pneumonia, and one with respiratory failure. Patients in the control group had 13 minor (3.7%) and 12 major (3.4%) acute complications. Major complications included five patients with wound infections, two with malpositioned instrumentation requiring revision, one with a dural tear, one with a retained drain, one with respiratory failure, one with C5 palsy, and one patient with pulmonary embolus. There was no significant difference in the rate of minor (p = 0.63), major (p = 0.47), or total (p = 0.90) acute complications between groups.

Revision surgery

In the control group, seven patients (2%) required non-acute reoperation surgery for adjacent segment disease (two patients), pseudarthrosis (3 patients), or instrumentation migration causing radiculopathy (1 patient) and painful hardware (1 patient). In the experimental group, 21 patients (12%) required non-acute reoperation surgery for adjacent segment disease (13 patients) and pseudarthrosis (9 patients). The difference between groups for rate of reoperation was statistically significant (p < 0.001).

Regression analysis

A step-down multiple regression model identified increasing age (coefficient 5.6, p < 0.001) and number of levels (coefficient 35, p < 0.001) as significant predictors of increased blood loss. The use of SSRI or SNRI medications did not quite reach independent statistical significance in the model (coefficient 39, p = 0.073) for predicting increased blood loss, although the data would be consistent with a strong trend toward increased blood loss. Other antidepressant categories did not reach a significant trend toward predicting increased blood loss.

Because PLF demonstrated the largest increase in blood loss with antidepressant usage, a separate step-down regression model was performed using this subgroup of patients. This regression model identified an increased number of levels (coefficient 123, p < 0.001), usage of a 5-HT2 antagonist (coefficient 839, p = 0.001), and usage of bupropion (coefficient 250, p = 0.014) as significant predictors of blood loss.

Discussion

It is known that depression and other psychiatric illness are relatively common among patients with spinal pathology. Research study also suggested the association between preoperative depression and poorer surgical outcome in the 1-year follow-up of patients with lumbar spinal stenosis [7]. In the current study, 13.8% of patients were found to be taking an antidepressant medication in the period prior to surgery. It has not, however, been widely known that the medications used to treat these psychiatric conditions might affect bleeding at the time of surgery. In the present study, we found a statically increased blood loss in patients on antidepressant agents as compared to matched controls. This effect was more pronounced, although not exclusively seen in patients taking SSRI/SNRI medications.

It is important to note that although the blood loss was statistically higher, the clinical effects of this may be modest with certain types of surgery. For instance, with ACDF, patients taking antidepressants experienced a mean 20.5% higher blood loss, but still only had a mean blood loss of 141 cc, an amount that would be well tolerated by most patients. However, in the subgroup of patients who took SSRI/SNRI medications and underwent a combined anterior/posterior lumbar fusion, the mean blood loss was 2.5 times greater (1,367 vs. 535 cc, p = 0.01) and likely would have clinical ramifications.

The mean length of hospital stay was found to be 20% greater for patients taking antidepressant medications (p = 0.001). Although blood loss could be one factor in this finding, it is unlikely that the magnitude of blood loss difference was a significant factor in certain procedural categories such as ACDF, as the overall blood loss was relatively small in both groups. Other issues such as pain tolerance and the patient-specific rehabilitation factors may be related to the diagnoses for which the antidepressants were prescribed and may affect length of stay.

Overall, the finding of increased blood loss was found to be most compelling, although not exclusive to the SSRI/SNRI type of medications. It is interesting to note that the central nervous system contains <5% of the body’s serotonin. As much as 95% of the body’s serotonin is synthesized by the enterochromaffin cells in the GI tract and released into the portal circulation where it is absorbed and accumulated by platelets, metabolized in the liver, or metabolized via endothelium of the pulmonary vasculature. More than 99% of whole blood serotonin is stored in platelets [8] and released during a thrombotic event causing vasoconstriction and platelet aggregation. Mature platelets are not able to syntheses serotonin and are dependent on the reuptake of serotonin from plasma [9].

Other studies have suggested a link between SSRIs and bleeding risk [4]. For instance, the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding was 3.6 times higher in patients taking SSRIs compared to those who do not use these medications. This effect was increased to 12.2 times the risk in the general population for patients who take SSRIs and NSAIDs simultaneously [10]. Barbui et al. in a case–control study also found a modestly increased risk of gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding with usage of SSRIs, but no increased risk with tricyclic antidepressants. They showed that other antidepressants (including mianserin, trazodone, and venlafaxine) were associated with a statistically significant increased risk of GI bleeding [11]. Elderly patients are at greater risk for bleeding sequelae [5], as well as those who take agents with a higher degree of serotonin reuptake inhibition [12, 13] (Tables 5, 6).

Table 5.

Degree of serotonin reuptake inhibitors: Ref. [12]

| High SRI | Intermediated SRI | Low SRI |

|---|---|---|

| Fluoxetine | Venlafaxine | Mirtazapine |

| Sertraline | Amitriptyline | Bupropion |

| Paroxetine | Fluvoxamine | Nortriptyline |

Table 6.

Antidepressant agents categorized on the basis of their affinity for 5-HTT and 5-HT2A receptors (high: Ki < 10 nmol/l; medium: Ki 10–1,000 nmol/l; and low: Ki > 1,000 nmol/l; or no data) Ref. [13]

| Drug class | Drug | Affinity for 5-HTT (nmol/l) | Affinity for 5-HT2A (nmol/) |

|---|---|---|---|

| TCAs | Desipramine | 95.4 | 105 (Rat) |

| Amitriptyline | 27.6 | 23 | |

| Nortriptyline | 207 | 5.0 (Rat) | |

| Doxepin | 68 | 26.0 (Rat) | |

| SSRIs | Fluoxetine | 5.42 | 196.7 |

| Citalopram | 6.09 | >10,000 | |

| Paroxetine | 0.26 | >10,000 | |

| Sertraline | 1.11 | >1,000 (Rat) | |

| Fluvoxamine | 5.55 | >10,000 (Rat) | |

| Escitalopram | 1.80 | – | |

| Other antidepressants | Trazodone | 367 | 35.8 |

| Venlafaxine | 68.7 | >1,000 (Rat) | |

| Duloxetine | 1.73 | 504 (Rat) |

Serotonin reuptake transporter (5-HTT); serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT)

Movig et al. showed an association between SSRI usage and the need for perioperative blood transfusion in orthopedic surgical patients, while non-serotonergic antidepressant agents did not demonstrate a similar association. Although their study included relatively small numbers of SSRI users, the mean blood loss was 1,019 ml for SSRI users versus 582 ml for nonusers, p = 0.001, and the risk of blood transfusion was four times higher in those on SSRI medications [4]. Layton et al. in a large observational cohort study found the risk of surgical bleeding to be independent of the duration of SSRI therapy [14].

SSRIs affect platelet aggregation, which can be measured by a platelet function assay (PFA). The PFA measures both platelet adhesion and aggregation (primary hemostasis). SSRIs do not affect other bleeding measures including the international ratio (INR), partial thromboplastin time (PTT) or prothrombin time (PT) which measure the enzymatic cascade leading to a fibrin clot. McCloskey et al. [6] demonstrated alterations of the platelet function assay in patients taking SSRIs compared to those on a non-serotonergic antidepressant. Mago et al. [10] suggested that PFA should be evaluated before elective surgery in patients taking SSRIs. although no data were offered to define the benefits of this test in the presurgical setting.

Certain limitations of the current study must be acknowledged. First, the study is retrospective in nature, making it impossible to exactly match the study cohort and the control group. However, this limitation is partially offset by including only patients from a single surgeon and institution to limit differences in surgical technique and skill in changing the amount of surgical bleeding. Also, all data were collected from hospital records, making recall bias negligible. Another limitation is the imprecise nature of determining surgical blood loss. Although some estimation of blood collected on surgical sponges is inherent to this data, it should be understood that an experienced, dedicated surgical perfusionist made the estimation in all cases, thus standardizing the process to the best possible extent. Another limitation is the fact that differences in blood loss were not correlated to other clinical variables, such as postoperative hemoglobin/hematocrit levels or the need for postoperative transfusions, and postoperative blood loss was not measured. While this limitation is acknowledged, it should be understood that the goal was simply to define whether a class of medications was associated with greater blood loss at the time of surgery. Any decisions as to whether psychiatric medications should be changed or discontinued prior to surgery should be made while weighing the risks and benefits of the medications. For most types of spine fusion surgery, the increase in blood loss was modest and thus the benefits of these medications likely outweighed the risk of bleeding. For larger spinal fusion procedures, where the risk of severe bleeding was higher, an alteration in medication usage may be warranted. Finally, although our overall study cohort was large, subgroup analyses for individual fusion categories included groups with insufficient data to yield meaningful results, and thus subgroups with small numbers of patients should be considered with caution.

Conclusion

The present study suggests a statistically significant link between SSRI/SNRI medications and increased bleeding with elective spinal surgery. For surgical procedures with a low blood loss, this effect was found to be modest. However for larger spinal procedures (anterior and posterior spinal fusion), it was found to be in the range associated with a clinical significance. Clinician and patients should be aware of the possibility of excessive bleeding with SSRI/SNRI medications and should consider electively tapering the antidepressant prior to the surgery or ordering platelet function assay. Changing to an antidepressant medication that does not inhibit (e.g., bupropion) or less potently inhibits (e.g., mirtazapine) serotonin reuptake may be considered in situations where major bleeding is anticipated due to the nature of the planned surgical procedure. Attention should also be paid to concomitant use of antiplatelet agents in patients on serotonergic antidepressants.

Conflict of interest

None.

Contributor Information

Amirali Sayadipour, Email: amiralisayadi@yahoo.com.

Rajnish Mago, Email: rajnish.mago@jefferson.edu.

Christopher K. Kepler, Email: chris.kepler@gmail.com

R. Bryan Chambliss, Email: r.chambliss@drexelmed.edu.

Kenneth M. Certa, Email: kenneth.certa@jefferson.edu

Alexander R. Vaccaro, Email: alexvaccaro3@aol.com

Todd J. Albert, Email: tjsurg@aol.com

D. Greg Anderson, Phone: +1-434-8258916, FAX: +1-215-5030580, Email: greg.anderson@rothmaninstitute.com, Email: davidgreganderson@comcast.net.

References

- 1.Schatzberg AF. New indications for antidepressants. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(Suppl 11):9–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Serebruany VL, Glassman AH, Malinin AI, Nemeroff CB, Musselman DL, van Zyl LT, Finkel MS, Krishnan KR, Gaffney M, Harrison W, Califf RM, O'Connor CM, Sertraline AntiDepressant Heart Attack Randomized Trial Study Group Platelet/endothelial biomarkers in depressed patients treated with the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor sertraline after acute coronary events: the Sertraline AntiDepressant Heart Attack Randomized Trial (SADHART) Platelet substudy. Circulation. 2003;108(8):939–944. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000085163.21752.0A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haelst IM, Egberts TC, Doodeman HJ, Traast HS, Burger BJ, Kalkman CJ, Klei WA. Use of serotonergic antidepressants and bleeding risk in orthopedic patients. Anesthesiology. 2010;112(3):631–636. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181cf8fdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Movig KL, Janssen MW, Waal Malefijt J, Kabel PJ, Leufkens HG, Egberts AC. Relationship of serotonergic antidepressants and need for blood transfusion in orthopedic surgical patients. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(19):2354–2358. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.19.2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andrade C, Sandarsh S, Chethan KB, Nagesh KS. Serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants and abnormal bleeding: a review for clinicians and a reconsideration of mechanisms. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(12):1565–1575. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09r05786blu. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCloskey DJ, Postolache TT, Vittone BJ, Nghiem KL, Monsale JL, Wesley RA, Rick ME. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: measurement of effect on platelet function. Transl Res. 2008;151(3):168–172. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sinikallio S, Aalto T, Airaksinen O, Lehto SM, Kröger H, Viinamäki H. Depression is associated with a poorer outcome of lumbar spinal stenosis surgery: a two-year prospective follow-up study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2011;36(8):677–682. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181dcaf4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skop BP, Brown TM. Potential vascular and bleeding complications of treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Psychosomatics. 1996;37(1):12–16. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(96)71592-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verdel BM, Souverein PC, Meenks SD, Heerdink ER, Leufkens HG, Egberts TC. Use of serotonergic drugs and the risk of bleeding. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;89(1):89–96. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mago R, Mahajan R, Thase ME. Medically serious adverse effects of newer antidepressants. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2008;10(3):249–257. doi: 10.1007/s11920-008-0041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barbui C, Andretta M, Vitis G, Rossi E, D’Arienzo F, Mezzalira L, Rosa M, Cipriani A, Berti A, Nose M, Tansella M, Bozzini L. Antidepressant drug prescription and risk of abnormal bleeding: a case–control study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009;29:33–38. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181929f7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mansour A, Pearce M, Johnson B, Sey MS, Oda N, Collegala N, Krishnadev U, Bhalerao S. Which patients taking SSRIs are at greatest risk of bleeding? J Fam Pract. 2006;55(3):206–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Verdel BM, Souverein PC, Meenks SD, Heerdink ER, Leufkens HG, Egberts TC. Use of serotonergic drugs and the risk of bleeding. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;89(1):89–96. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Layton D, Clark DW, Pearce GL, Shakir SA. Is there an association between selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and risk of abnormal bleeding? Results from a cohort study based on prescription event monitoring in England. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;57(2):167–176. doi: 10.1007/s002280100263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]