Abstract

Although online and field-based samples of men who have sex with men (MSM) have been compared on a variety of markers, differences in drug use have not been well examined. In addition, generalization from studies comparing recruitment methods is often limited by a focus on either HIV seropositive or seronegative MSM. We compared two New York City-based samples of MSM recruited simultaneously between July 2009 and January 2010—one sample recruited in the field (n = 2402) and one sample recruited via the Internet (n = 694). All recruitment efforts targeted men without restriction on age or self-reported HIV status. Our results show marked differences in drug and alcohol use between online and field-based samples of MSM. Specifically, men surveyed online were significantly more likely to have tried a variety of drugs, including methamphetamine, cocaine, and ecstasy. Men recruited online were also more likely to report older age, HIV positive serostatus, and “never” using condoms. Internet-based recruitment was found to be more cost-effective in terms of recruitment yield than was field-based recruitment.

Keywords: recruitment, MSM, Internet, field, stimulants

Thirty years into the epidemic, gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (MSM) continue to be disproportionally affected by HIV infection. A recent meta-analysis of population-based surveys examining HIV rates among MSM concluded that, although only 4% of men in the United States reported sex with another man in the past five years, their HIV diagnosis rate is 60 times higher than the rate for other men, and 54 times higher than the rate for women1. The high rates of HIV infection among MSM are mirrored by high rates of drug use among MSM. The 2008 National HIV Behavioral Surveillance (NHBS) system surveyed 550 MSM in NYC and found that 51% reported the use of non-injection drugs in the past year; 33% of MSM reported at least weekly use2. Substance use among MSM has been consistently linked to sexual risk practices and HIV infection. MSM who use recreational drugs are more likely to report sexual risk behavior, and are more likely to be HIV-positive or test positive for other sexually transmitted infections3–9. Higher rates of drug use have been observed among MSM who reside in gay neighborhoods and socialize predominately with other gay men10, so the potential for substance use-risky sex connections to be reinforced within social and sexual networks among MSM is a concern.

In large urban areas like New York City, the use of some recreational drugs has become heavily associated with frequenting dance clubs, bars, and parties among MSM11. These drugs, commonly referred to as “club drugs,” include stimulants such as ecstasy, cocaine, and methamphetamine, and other drugs like gamma hydroxybutyric acid (GHB), ketamine, and nitrites, widely known as “poppers”12,13. Club drugs have been found to be particularly problematic for gay, bisexual and other MSM in terms of their relation to high risk sexual behavior12,14–19. A series of studies examining club drug use among those frequenting nightclubs and other social venues in New York City found that gay and bisexual men were significantly more likely than other men and women to report the use of certain club drugs, particularly methamphetamine11,20,21. A study of MSM recruited at community events in New York City, using a repeated cross-sectional design, found that among HIV-negative men, rates of recent (past 90 days) use for most club drugs decreased significantly from 2002 to 2007, yet rates of cocaine and poppers remained consistent22. Among HIV-positive MSM, however, rates of recent use for most drugs did not decrease, and overall, significantly more HIV-positive MSM reported club drug use across all years.

With such high rates of drug use and a clear connection between drug use and HIV risk behaviors, there is an urgent need for interventions targeting both substance use and risky sexual practices among MSM23. However, recruiting MSM into behavioral intervention trials has often been a challenging task for researchers, and few behavioral interventions have been tested with drug-using MSM who are not in treatment24–26. This is not surprising, considering the overall reluctance of those with substance use problems to seek treatment. For example, only one in five of those with a substance use disorder actually seek treatment, and premature drop-out from such treatment is high27. Specific concerns emerge in targeting MSM for intervention, as there may be reluctance to enroll in interventions due to fears of homophobia among treatment providers, which has been cited as the most common reason for not seeking drug treatment28. MSM who enroll in traditional substance abuse treatment are likely to encounter programs that focus on heterosexual relationships and fail to address the unique cultural issues related to substance use in the gay community29, and there is evidence that the majority of programs that claim to offer gay-specific services actually do not30.

Although recruitment is a critical component of any randomized clinical trial of a behavioral intervention, few researchers publish detailed information on recruitment procedures or the differential yields of various recruitment approaches. Recently, however, many behavioral scientists who study HIV have turned to the Internet for recruitment, particularly of MSM31,32. Recruitment for a fully Internet-based study, one which does not require any face-to-face interaction with researchers33, poses different issues and concerns than using the Internet to recruit participants for face-to-face delivered interventions. For example, an intervention that recruits online but has a face-to-face component helps to alleviate concerns about the same individual completing a study multiple times to garner incentives, and reduces the likelihood of deception about demographic eligibility34–36. Here, we will focus on face-to-face studies that employed both Internet and field recruitment strategies. Similarly, we will limit our focus to studies that enroll MSM in behavioral interventions, omitting those formative or epidemiologic studies that compared samples of MSM recruited online versus other methods37–43.

Although HIV sexual risk behaviors in MSM have been consistently linked to substance and alcohol use, no studies to date have examined the differential effectiveness of field-based versus Internet-based recruitment of MSM for an intervention targeting both substance use and HIV sexual risk behaviors. Rather, previous studies that have carefully examined recruitment efforts for intervention trials targeting MSM have compared differential yields of participants from various strategies. One study involved considerable efforts at developing marketing messages to target various subgroups of MSM for enrollment in a telephone-based sexual risk reduction intervention44. This study found that sending recruiters into the field to targeted gay venues was a key to recruitment success. These field-based efforts were more effective at reaching younger MSM (ages 40 and under), but less effective at reaching African American, non-gay identified, and HIV-positive MSM; the Internet, however, was more effective at reaching HIV-positive MSM and men with less motivation to change their sexual risk behaviors. This latter point is particularly relevant for interventions targeting substance-using MSM, as motivation to enroll in intervention studies despite substance use-related problems among MSM is typically low26,45–47. Recruitment methods for a weekend intervention targeting sexual health among MSM in six US cities, including New York City, found that the best method for recruitment was friend referral, that print ads were more effective in reaching White MSM, and that MSM recruited via the Internet were significantly less likely to actually attend the intervention48. Interestingly, though, once MSM were enrolled and attended the intervention, retention for follow-up assessments did not differ by recruitment method. Although the EXPLORE intervention trial did not utilize Internet-based recruitment efforts, field-based recruitment efforts were more effective at reaching younger MSM, MSM of color, and HIV-positive MSM than were print ads and other methods of recruitment49. The EXPLORE study also found that, although there were no differences in HIV incidence by recruitment strategy, MSM reporting 10 or more sexual partners were more likely to be recruited via field-based efforts, and MSM reporting unprotected anal sex were more likely to be recruited via clinic-based efforts. None of these previous studies, however, have made direct comparisons between the differential effectiveness of field-based versus Internet-based recruitment of MSM for an intervention targeting substance use and HIV sexual risk behaviors.

Clearly, understanding systematic differences between field-based and Internet-based samples of MSM in terms of HIV sexual risk and drug use has the potential to guide and inform future efforts at enrolling MSM in behavioral interventions. In addition, we believe it is also important to address the issue of how the two recruitment strategies may compare in terms of cost and overall feasibility. Researchers have identified Internet-based recruitment as a “low-cost and efficient method”32 that can be deployed “with few, if any, related expenses”34 and generally regard Internet recruitment as inexpensive33,39,41,48,50. However, to our knowledge, only Fernandez et al.32 have presented an explicit and thorough cost analysis comparing the effectiveness of online and field-based recruitment of MSM, and this study was focused exclusively on Latino MSM and was not for an intervention trial.

In the present study, we compare a sample of MSM recruited in the field at a variety of venues to a sample of MSM recruited via the Internet. Both recruitment strategies were implemented simultaneously over a 5-month period, and both targeted MSM living in or near the New York City area. Differences in demographic characteristics, sexual risk behaviors, and drug use were examined, as was a consideration of the cost effectiveness of both recruitment strategies.

Method

The data presented here were collected simultaneously in the field and online between July 2009 and January 2010. Both field and online recruitment strategies directed respondents to complete an 11-item screening survey to determine preliminary eligibility to participate in one of two studies; these are the data we analyzed for the present paper. Men deemed eligible on this survey were asked to give their contact information. Those who did so were contacted for a full eligibility screening by phone. All recruitment materials and procedures for both studies were approved by the IRB at Hunter College of the City University of New York.

Recruitment efforts were conducted for two in-person randomized controlled behavioral intervention trials targeting drug-using MSM in the New York City area. The first study was the Men’s Health Project, a four-session risk reduction intervention based on Motivational Interviewing designed to reduce club drug use and sexual risk taking behaviors among non-treatment seeking HIV-negative and unknown status MSM51–53. The second study was Project ACE (Adherence, Counseling and Education), an eight-session risk reduction intervention based on Motivational Interviewing and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy designed to reduce methamphetamine use and improve HIV medication adherence among HIV-positive methamphetamine-using MSM. Both online and field-based recruitment strategies aimed at enrolling participants into both intervention trials.

Participants

Between July 2009 and January 2010, 3096 MSM completed the 11-item screening survey either in the field (n = 2402; 77.58%) or on the Internet (n = 694; 22.41%). Almost half (46%) of participants were between 18 and 29 years old; 29.7% were in their thirties (30–39 years old,) and the remaining 24.3% were aged 40 and above. Also, a majority of the overall sample identified as white (55.3%) followed by Hispanics/Latinos (16.5%), other race/ethnicity (15.3%), and blacks (12.9%). Most MSM self-reported that they were HIV-negative or of unknown status (81.9%). See Table 1 for additional participant information.

Table 1.

Demographic Composition

| Overall | Field-Based | Internet-Based | Test Statistic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N(%) | 3096 | 2402 (77.6%) | 694 (22.4%) | |

| Age | χ2 (2)=51.64** | |||

| 18–29 | 1424 (46.0%) | 1099 (45.8%) | 325 (46.8%) | |

| 30–39 | 919 (29.7%) | 777 (32.3%) | 142 (20.5%) | |

| 40 and older | 753 (24.3%) | 526 (21.9%) | 227 (32.7%) | |

| Race | χ2 (3)=32.96** | |||

| White | 1707 (55.3%) | 1262 (52.6%) | 445 (64.8%) | |

| Black | 398 (12.9%) | 325 (13.5%) | 73 (10.6%) | |

| Latino | 510 (16.5%) | 427 (17.8%) | 83 (12.1%) | |

| Other | 473 (15.3%) | 387 (16.1%) | 86 (12.5%) | |

| HIV-Status | χ2 (1)=368.97** | |||

| Positive | 556 (18.1%) | 260 (10.9%) | 296 (43.0%) | |

| Negative/Unknown | 2510 (81.9%) | 2117 (89.1%) | 393 (57.0%) | |

| HIV-Medications | χ2 (1)=1.39 | |||

| Yes | 441 (79.5%) | 201 (77.3%) | 240 (81.4%) | |

| No | 114 (20.5%) | 59 (22.7%) | 55 (18.6%) |

p <.01;

p <.05

Materials and Procedures

Measurements

The 11-item screening survey began by asking men to report basic demographic information (age, race/ethnicity, and whether they had sex with other men and resided in the New York City area). Men then were asked, “which of the following drugs, if any, have you used in the last 90 days?” (e.g., cocaine, ecstasy, meth, ketamine, GHB, poppers, or none of the above) and the amount of alcohol they used in the past week. Finally, men reported their HIV status, and whether they engaged in anal sex with another man in the past 90 days. MSM who reported HIV-negative or unknown status were asked how often they used condoms with male casual partners in the last 90 days, and where therefore categorized as consistent condom users (100% of the time), inconsistent condom users (less than 100% of the time), or no condom use (never use condoms). HIV-positive MSM were asked whether they were currently taking HIV medication. These last two items were directly tied to the unique eligibility requirements of the two studies for which recruitment was ongoing.

Recruitment Strategies

The field-based recruitment strategy was developed using a convenience sampling methodology to approach men at bars and nightclubs28. Viable venues were identified by ethnographic research and reliance on a highly popular weekly magazine advertising and promoting gay bars and parties in the New York City area. These approaches were also used to determine socially viable times within venues (i.e., times when attendance at these venues would be optimal). Staff attended venues on these specified times and approached men either outside or inside the venue, asking them to complete the screening survey. Overall, during the five months of recruitment reported in this study, 230 field recruitment shifts were sent out—each shift included 2 staff members and lasted an average of 3 hours. This field-based strategy also included venues such as community centers and AIDS Services Organizations (ASOs). Partnerships were established whereby 2–3 recruitment staff members were allowed to set up tables at these venues for 2–3 hour shifts, displaying recruitment materials such as brochures and business cards, and administering the survey to any willing men who would approach the table.

To survey men in the field, staff used electronic devices (Palm Pilot Z22). After obtaining verbal consent, the recruiter would ask the participant basic demographic questions and then hand the device to the participant who completed the remaining questions. This technology allowed participants to read more sensitive questions and enter their responses privately, increasing confidentiality and encouraging honest disclosure. It also enabled skip sequencing, reducing the number of questions asked, as well as the time of administration. Whenever a participant was determined eligible for a study, recruitment staff collected their contact information in paper and pencil format.

An online version of the screening survey used in field-based recruitment was supported by SurveyMonkey.com. Our Internet-based recruitment strategy consisted of 102 one-person shifts lasting 2.5 hours on average. During these shifts, recruiters visited and posted recruitment messages on three different types of websites. First, recruiters created study profiles on dating sites serving MSM (e.g. Adam4Adam.com, DaddyHunt.com). These profiles listed study information, partial eligibility criteria, and a link to the online survey (when allowed so by the site). Whenever recruitment staff members were logged into these profiles, men searching for male partners in the New York City area might see and interact with them. Also, whenever chat room capabilities and forum spaces were supported by a site (e.g., Gay.com, Squirt.org) our staff posted weekly short messages encouraging users to contact us, including a link to the survey (when allowed so by the site). We employed a mix of various websites catering to different groups of MSM, in order to increase the diversity of the final online sample. For example, we used websites such as Blackgaychat.com, which cater specifically to minority MSM.

Second, Craigslist.org, a site offering free classified ads, was used in a similar way as forums. Staff posted a daily message with study information and recruitment criteria, which was visible to men performing searches within the category “New York City > Personals > Sex with No Strings Attached > Men seeking Men”. Men interested in the posting had the option of contacting staff via email or phone, and potential participants who sent an email received a link to the online survey.

Finally, the social networking site Facebook.com was employed in two ways. First, the study’s sponsoring center maintains a page which contains information about ongoing studies. Project staff posted a message containing a link to the online survey in the wall of this page every day. As Facebook members became “fans” of the page, a snowball effect ensued whereby the messages posted in our wall became visible to our fans and also to their friends, who then had the option to become fans of our page as well. Second, Facebook Ads were created to drive more traffic to the sponsoring center’s page, which directed individuals to the survey. These ads consist of an image and a short text linked to either a Facebook page or an outside landing webpage. Ads were targeted to a subset of Facebook users—those aged 18 and older, who lived in the New York City area, were male, and indicated they were “interested in men” on their Facebook profile.

Analytic Strategy

Because all demographic and dependent variables of interest were assessed categorically, differences across the two recruitment strategies—field-based and Internet-based—were evaluated using chi-square tests of independence. For those demographic and dependent variables that included more than three response categories, follow-up analyses were conducted using Fischer’s Exact Tests where significant differences were found across recruitment strategies.

Results

Demographics and HIV status by recruitment strategy

Demographic comparisons of field-based versus Internet-based samples are presented in Table 1. Individuals recruited in the field were significantly more likely to be between the ages of 30–39, and individuals recruited online were significantly more likely to be 40 or older. MSM recruited via the Internet were more likely to report being White, and MSM recruited in the field were more likely to report being Latino, Black, or “Other” race/ethnicity. Also, MSM recruited online were significantly more likely to report being HIV-positive than were MSM recruited in the field.

Drug and alcohol use by recruitment strategy

MSM recruited online were significantly more likely to report recent (past 90 days) use of each of the assessed club drugs than men recruited in the field (see Table 2). Significantly more MSM from Internet-based recruitment efforts reported any club drug use in the past 90 days, compared to MSM from field-based recruitment. Frequent alcohol use (15 drinks in the previous week, or an average of more than 2 drinks per day) was significantly more common among MSM recruited in the field than among those recruited online.

Table 2.

Recent (past 90 days) Substance Use and Sexual Activity Days

| Overall | Field-Based | Internet-Based | Test Statistic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex with male partner Last 90 days | χ2 (1)=67.51** | |||

| Yes | 632 (89.6%) | 169 (75.8%) | 463 (96.1%) | |

| No | 73 (10.4%) | 54 (24.2%) | 19 (3.9%) | |

| Condom Use† | χ2 (2)=71.87** | |||

| Consistent | 823 (48.9%) | 767 (53.0%) | 56 (23.9%) | |

| Inconsistent | 645 (38.3%) | 520 (35.9%) | 125 (53.4%) | |

| Never | 214 (12.7%) | 161 (11.1%) | 53 (22.6%) | |

| Substance Use | ||||

| Methamphetamine | χ2 (1)=225.95** | |||

| Yes | 240 (7.9%) | 100 (4.2%) | 140 (22.4%) | |

| No | 2787 (92.1%) | 2302 (95.8%) | 485 (77.6%) | |

| Cocaine | χ2 (1)=17.86** | |||

| Yes | 788 (26.0%) | 584 (24.3%) | 204 (32.6%) | |

| No | 2239 (74.0%) | 1818 (75.7%) | 421 (67.4%) | |

| Ecstasy | χ2 (1)=15.78** | |||

| Yes | 356 (11.8%) | 254 (10.6%) | 102 (16.3%) | |

| No | 2671 (88.2%) | 2148 (89.4%) | 523 (83.7%) | |

| Ketamine | χ2 (1)=19.87** | |||

| Yes | 109 (3.6%) | 68 (2.8%) | 41 (6.6%) | |

| No | 2918 (96.4%) | 2334 (97.2%) | 584 (93.4%) | |

| GHB | χ2 (1)=79.66** | |||

| Yes | 141 (4.7%) | 70 (2.9%) | 71 (11.4%) | |

| No | 2886 (95.3%) | 2332 (97.1%) | 554 (88.6%) | |

| Poppers | χ2 (1)=197.52** | |||

| Yes | 669 (22.1%) | 401 (16.7%) | 268 (42.9%) | |

| No | 2358 (77.9%) | 2001 (83.3%) | 357 (57.1%) | |

| At least 1 club drug | χ2 (1)=163.89** | |||

| Yes | 1293 (42.7%) | 885 (36.8%) | 408 (65.3%) | |

| No | 1734 (57.3%) | 1517 (63.2%) | 217 (34.7%) | |

| Alcohol use last week | χ2 (1)=38.99** | |||

| Less than 15 drinks | 1373 (71.6%) | 1025 (68.2%) | 348 (83.9%) | |

| 15 drinks or more | 544 (28.4%) | 477 (31.8%) | 67 (16.1%) |

p <.01;

p <.05

HIV-Negative or Unknown only

Sexual activity by recruitment strategy

Table 2 shows sexual behavior comparisons of men recruited via field versus online. A significantly greater percentage of men recruited online reported having anal sex with a male partner in the past 90 days, compared to men recruited in the field. Also, HIV-negative and unknown status men were asked the frequency of condom use with male casual partners during the 90 days prior to completing the survey. MSM recruited online were significantly more likely than MSM recruited in the field to report using condoms inconsistently or never, while those recruited in the field were much more likely to report the consistent use of condoms (i.e., every time).

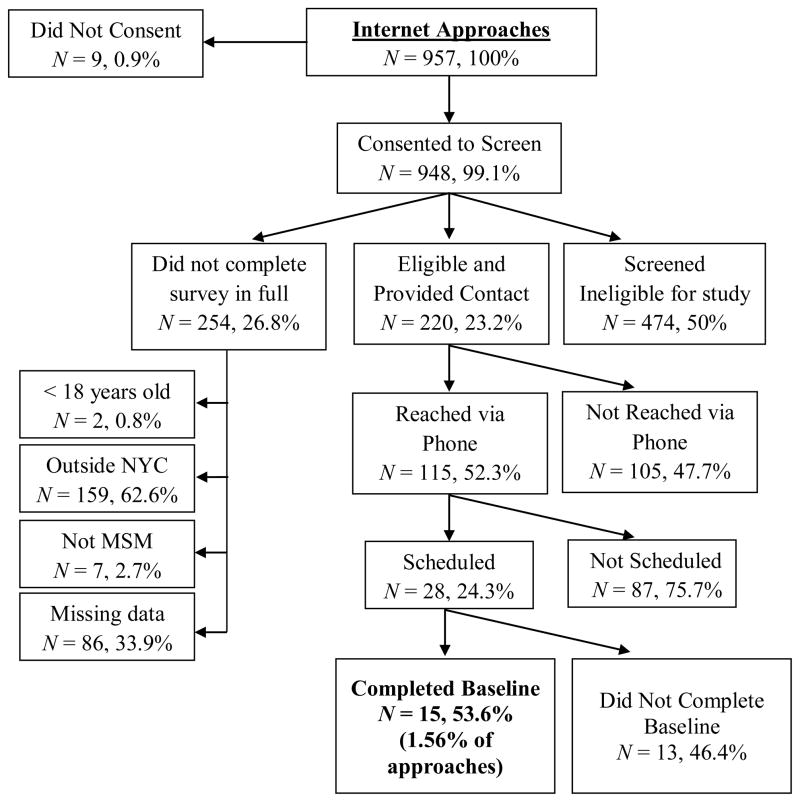

Effectiveness and cost by recruitment strategy

Data related to the effectiveness (in terms of participant identification and retention) and cost (in person-hours) for each recruitment strategy are provided in Table 3 and Figures 1 and 2. Notably, Figures 1 and 2 provide data related to the percentage of participants retained within each stage of the recruitment process. Table 3 contains data related to the percentage of total participants approached who were retained at each stage. In all, 3877 men consented to take the survey during the five-month period under study, and 3096 of those belonged to our target population (i.e., at least 18 years old, lived in New York City area, reported sex with another man) and completed the survey in full. The majority of those (77.6%) were recruited in the field, compared to 22.4% of men recruited online. Participants excluded from screening because they were not part of the study population were more likely to have been approached in the field (39.1%) than online (27.5%) χ2(1, N = 3877) = 45.01, p = .001.

Table 3.

Effectiveness and cost by recruitment strategy

| Overall | Field-Based | Internet-Based | Test Statistic | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potential Participants Approached† | 3096 | 2402 (77.6%) | 694 (22.4%) | |

| Eligible Contacts | χ2 (2)=7.59* | |||

| Yes | 854 (27.58%) | 634 (26.39%) | 220 (31.70%) | |

| No | 2242 (72.42%) | 1768 (73.61%) | 474 (68.30%) | |

| Reached via phone | χ2 (2)=16.74** | |||

| Yes | 544 (63.70%) | 429 (67.67%) | 115 (52.27%) | |

| No | 310 (36.30%) | 205 (32.33%) | 105 (47.73%) | |

| Scheduled for Baseline | χ2 (2)=0.53 | |||

| Yes | 147 (27.02%) | 119 (27.74%) | 28 (24.35%) | |

| No | 397 (72.98%) | 310 (72.26%) | 87 (75.65%) | |

| Scheduled (as % of Reached via Phone) | ns | |||

| Yes | 27% | 28% | 24% | |

| No | 73% | 72% | 76% | |

| Completed Baseline | χ2 (2)=0.02 | |||

| Yes | 77 (52.38%) | 62 (52.10%) | 15 (53.57%) | |

| No | 70 (47.61%) | 57 (47.90%) | 13 (46.43%) | |

| Completed Baseline (as % of Eligible Contacts) | ns | |||

| Yes | 9% | 10% | 7% | |

| No | 8% | 9% | 6% | |

| Cost by recruitment strategy | ||||

| Total Person Hours | 1566 | 1292 | 274 | |

| Person Hours per Completed Survey | 0.51 | 0.54 | 0.39 | |

| Person Hours per Contact | 1.83 | 2.04 | 1.24 | |

| Person Hours per Baseline | 20.33 | 20.84 | 18.23 | |

p <.01;

p <.05

Approached MSM within the target population

Figure 1.

Field-Based Recruitment Process

Figure 2.

Internet-Based Recruitment Process

During the five months of data collection, 3954 men were approached in the field by recruitment staff, compared to 957 who responded to Internet recruitment efforts (See Figures 1 and 2 for detailed breakdowns of field-based and Internet-based recruitment). The majority of men consented to take the preliminary survey, but of those, less than a quarter were identified as potentially eligible for one of the studies and provided contact information. Compared to Internet-based recruitment, field-based recruitment yielded significantly higher numbers of MSM who met preliminary eligibility criteria and provided contact information (a telephone number or email address to be contacted for final eligibility confirmation and scheduling)—of the 854 providing contact information, more than a quarter were approached in the field (see Table 3). However, MSM who completed the survey online were significantly more likely than those recruited in the field to be eligible and give their contact information.

Nevertheless, potential participants who provided contact information who were recruited in the field were more likely to be reached later via phone to complete a full eligibility screening than were those reached online (see Table 3). These recruitment differences stop at the phone screening level—once we were able to reach and screen them, MSM recruited in the field and via the Internet were just as likely to be fully eligible and schedule an appointment, and just as likely to actually present in person to complete their baseline assessment. Also, only 27.7% of MSM who were recruited in the field and 24.3% of those recruited online were scheduled for a baseline assessment, as many men were either deemed ineligible via the more detailed telephone screener, or were no longer interested in participating. Of those scheduled, nearly half did not complete the baseline assessment, primarily because they failed to show for their scheduled appointment. In total, 1.56% of men approached either in the field or online completed the baseline assessment. Consistent with Table 3, this resulted in 10% of eligible contacts from the field and 7% of eligible contacts from the Internet completing a baseline appointment.

A total of 332 recruitment shifts (207 in the field and 125 online) were worked in the five-month period covered. On average, 215.33 person hours were spent every month on field-based recruitment, compared to an average of 45.58 hours per month spent doing Internet-based recruitment. We report cost in terms of person-hours, as we believe this will be most useful to other researchers when estimating the cost of their own recruitment strategies. Field recruitment took significantly more person-hours per month on average than did Internet recruitment, t(12) = 7.12, p < .001, MField = 202, SDField = 55.3, and MOnline = 43, SDOnline = 21.0, resulting in significant cost savings from Internet-based recruitment. On average, each baseline participant who was recruited online took 2 hours and 45 minutes less staff-time than each baseline participant recruited in the field. See Table 3 for detailed information regarding effectiveness and cost by recruitment strategy.

Discussion

The recruitment of MSM into behavioral intervention trials has important implications for the success of these trials and the generalizability of their findings54. This study compared simultaneously conducted field-based and Internet-based recruitment strategies that broadly targeted MSM living in the New York City metropolitan area. Our results showed marked differences between field-based and Internet-based samples of MSM with regard to demographic characteristics, substance use, and sexual risk behavior. Field-based recruitment reached a greater proportion of adult MSM (aged 30–39) and MSM of color, while Internet-based recruitment reached a greater proportion of older MSM (aged 40 and above) and MSM who were White. This is true despite the fact that our Internet-based recruitment efforts included sites such as Blackgaychat.com, which cater specifically to minority men. These results mirror those reported by prior studies48,55. In particular, Du Bois et al.55 found decreased participation in online HIV and other health research among racial and ethnic minority MSM. They suggested that the quality of Internet access may be a barrier to MSM searching for HIV information and learning about HIV research opportunities online. Such a conclusion is consistent with the results of this study.

While MSM recruited in the field were more likely to drink alcohol frequently (i.e., 2 or more drinks per day on average), those recruited on the Internet were more likely to have recently used a wide variety of recreational drugs. These differences are particularly striking when viewed in the context of population-based studies of substance use prevalence among MSM. Among the MSM enrolled in the NHBS2 from the New York City area, 26% reported using cocaine, 6% reported using methamphetamine, and 13% reported using poppers in the past year. Rates of cocaine, methamphetamine, and poppers reported among MSM recruited in the field in our research were similar to those observed among NHBS participants. In contrast, MSM recruited on the Internet in our research had higher rates of use for all three drugs (32.6%, 22.4%, and 42.9% respectively). Based on these findings, interventions targeting drug-using MSM would benefit from including Internet-based strategies in their overall recruitment efforts; however, these results do not necessarily suggest that MSM who utilize the Internet are more likely to use substances. First, targeting and self-selection processes may explain the higher endorsement of substance use online than in the field. Recruitment messages online indicated that our studies were relevant to MSM who used substances. Thus, individuals who did not engage in substance use may simply have avoided responding to our messages, increasing the proportion of MSM who endorsed substance use in the online sample compared to the field-based sample. In the field, this type of selection is unlikely to happen, as recruitment staff are not able to estimate beforehand whether the MSM they approach might engage in the behaviors of interest or not. This way, the Internet may allow for more targeted recruitment efforts. Second, some have suggested that online survey-takers may feel an increased sense of anonymity, and thus the influence of social desirability may be lowered online39, facilitating self-disclosure of potentially stigmatizing behaviors (e.g., substance use). More research is needed to further understand how factors such as these may influence Internet-based samples compared to samples recruited in the field.

Field-based recruitment reached a greater proportion of men who identified as HIV-negative compared to men in our Internet-based sample, which is consistent with prior findings56, but contradicts those reported elsewhere more recently (see Barresi et al.49, who found higher rates of seropositivity in field- compared to Internet-based samples). Relatedly, our Internet-based sample overall endorsed higher levels of sexual risk behavior (e.g., unprotected sex,) in accordance to previous studies (for example, Evans et al.37 conducted a study in Great Britain and found that MSM recruited over the Internet were more likely to report unprotected anal sex.) This may be related to the specific mix of websites being used (e.g., websites like “Bareback.com” may cater to men who do not use condoms, and thus utilizing this website for recruitment would likely result in increased rates of unprotected sex reported by the online sample.) The purpose of this study has been to examine the effectiveness of two broadly defined recruitment strategies (i.e., field and online recruitment;) however, a more detailed venue-level analysis might clarify which specific field venues and websites are most effective in recruiting sexually risky MSM. Nevertheless, our results suggest that, although Internet-based samples may overestimate the levels of sexual risk in the broader MSM population, the Internet may be an ideal venue to find MSM for HIV behavioral interventions targeting those who engage in risk behavior. Finally, we evaluated the two recruitment strategies in terms of cost and overall feasibility. Field-based recruitment strategies are substantially more time-consuming than Internet-based strategies. Recruiting a single participant in the field required an additional 2.5 person-hours on average compared to a participant recruited online. This difference in person-hours may be of particular concern to researchers who have limited recruitment budgets and/or those who lack access to volunteer recruiter staff.

Although field-based recruitment reached a higher number of MSM and generated many more contacts than Internet-based recruitment, a higher percentage of MSM screened on the Internet actually met eligibility criteria. This suggests that online strategies have an advantage with regard to efficiency. However, other aspects of these data suggest that this advantage may be limited. Those who gave their contact information over the Internet were less likely to be reached for phone screening than those who gave their contact information in the field. In addition, once we were able to successfully reach a participant for phone screening, MSM recruited in the field were just as likely as those recruited on the Internet to meet full eligibility, enroll, and show up for a baseline appointment—these results are similar to those reported by Hatfield et al.48.

The overall yield of our recruitment efforts was low across recruitment strategies. Less than 2% of all MSM approached (whether in the field or on the Internet) actually enrolled in our studies (see Figures 1 and 2). This may be related to our stringent eligibility criteria: more than half of the men we approached were deemed ineligible upon screening (50% of those who screened over the Internet; 60% of those who screened in the field,) although these percentages are very similar to prior recruitment studies45. Nevertheless, these data also demonstrate the challenges faced when recruiting MSM for observational and intervention HIV/AIDS studies that have been elaborated elsewhere28–30. Jenkins57 summarized the conclusions of a consultation conducted by program staff from the Division of Epidemiology, Services and Prevention Research at the National institute of Drug Abuse related to this issue. The challenges identified by the group included 1) reticence to disclose substance use (which may be an inclusion criteria), 2) distrust of research (particularly among racial/ethnic minority communities), 3) prevention fatigue, and 4) negative public perceptions of communities targeted by intervention efforts. They also identified generational perceptions of the epidemic, and increased concentration of non-gay individuals within social circles as barriers specific to the recruitment of younger MSM.

Limitations

These results should be viewed in light of several limitations. Convenience sampling was used both in field and Internet recruitment. In addition, recruitment was limited to those places (bars and clubs as much as websites) that tolerated and/or approved the presence of recruiters or recruitment materials. This study was further limited by the brief nature of the screening survey. For example, we had only limited screening data on substance use. Participants simply selected from a list any drugs they had used during the previous 90 days; our preliminary screening survey did not collect any information regarding modes of administration or quantity used. Although it would be interesting and informative to examine this (e.g., whether online and field recruitment strategies may reach different proportions of injection drug users compared to non-injection drug users), our dataset was limited and did not allow these types of analyses. Further, due to procedural steps taken to insure the confidentiality of participants, it is not possible to link data from the full assessments completed by those who participated in the studies. Future research may address this limitation by employing a more extensive survey.

Similarly, the inability to link recruitment and enrollment data prevents us from comparing drop-out rates over time between those recruited in the field and on the Internet. Although our analyses showed that MSM recruited via the different methods were just as likely to enroll and show up for a baseline appointment, it is plausible that one of the two groups might be less likely to complete the intervention trial in full. Such a differential drop-out rate would add a layer of complexity to any analyses of cost-effectiveness (i.e., one method might prove more effective in recruiting participants to enroll initially, but less effective long-term if participants have a tendency to drop out). Future studies might address this possibility by reporting on drop-out rates by recruitment strategy.

Additionally, studies focusing on recruitment of MSM might explore how various strategies may differentially reach specific subgroups of MSM at heightened risk for HIV-infection—for example, young MSM from racial/ethnic minority groups58–61. This group in particular has been identified not only as being at increased risk for HIV infection, but also as one of the hardest subgroups of MSM to recruit from57. Consequently, it would be fruitful for future recruitment studies to focus on this group—particularly on the differential capacity of Internet- and field-based recruitment to reach it55. Similarly, the current study examined the overall effects of aggregate recruitment efforts in the field and on the Internet. Future research should focus on the individual components of these larger recruitment efforts in order to identify the most effective agents in each (e.g., studies of Internet-based recruitment might examine the relative effectiveness of efforts on various websites, or compare email campaigns to banner ads; studies of field recruitment might compare active to passive strategies across various types of venues).

Finally, the current study also presented data on the overall cost of recruitment strategies in the form of person-hours. While we believe these data may significantly inform the selection of recruitment strategies, person-hours are not the only form of cost associated with recruitment. For example, other costs include material expenses (computers, palm pilots, etc.) or travel expenses (transportation to field recruitment venues). Future studies should incorporate more comprehensive cost data to be able to fully compare recruitment strategies in terms of total cost per contact.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that the choice of recruitment strategy is a function of both target population and resource (i.e., efficiency) concerns. Field-based recruitment was more effective in reaching adult MSM, MSM of color, and men who report consistent use of condoms. Internet-based recruitment was more effective in reaching MSM aged 40 and older, MSM who report the use of a wide range of substances, and those who report an HIV-positive serostatus and “never” using condoms. While field-based recruitment generated a greater number of contacts, this strategy was costly in terms of person-hours, and it seems most efficient for researchers targeting non-drug using MSM. Although online recruitment reached a smaller number of MSM overall, it was inexpensive relative to the person-hours required for field recruitment. Furthermore, online recruitment allowed for better targeting (i.e., higher rates of MSM actually met eligibility criteria). The current study provides data useful to intervention researchers seeking to surmount the challenges of recruiting MSM by comparing the sample characteristics, effectiveness, and efficiency of Internet-based versus field-based recruitment efforts.

Acknowledgments

The Young Men’s Health Project was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) (R01 DA020366, Jeffrey T. Parsons, Principal Investigator) and the authors gratefully acknowledge Dr. Corina L. Weinberger, the Project Director, and the contributions of the Young Men’s Health Project team—Michael Adams, Anthony Bamonte, Kristi Gamarel, Chris Hietikko, Catherine Holder, John Pachankis, Anthony Surace, and Brooke Wells. The ACE Project was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) (R01 DA023395, Jeffrey T. Parsons, Principal Investigator) and the authors gratefully acknowledge Dr. Julia Tomassilli, the Project Director, and the contributions of the ACE Project Team - Michael Adams, Kristi Gamarel, Chris Hietikko, Catherine Holder, John Pachankis, Ja’Nina Walker, and Margaret Wolff. The authors would like to thank Kevin Robin, the Director of Recruitment at the time these data were collected, and all of the members of the CHEST Recruitment Team. The authors would also like to thank Dr. Richard Jenkins for his support of the Young Men’s Health Project and Dr. Shoshana Kahana for her support of the ACE Project.

References

- 1.Purcell DW, Johnson C, Lansky A, et al. Calculating HIV and syphilis rates for risk groups: estimating the national population size of MSM. National STD Prevention Conference; Atlanta, GA. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.NYCDOMHH. Substance use and sexual health among men who have sex with men, injection drug users, and high-risk heterosexuals: Results from the National Health Behavior Surveillance Study in New York City. [Accessed October, 2011.]; http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/downloads/pdf/dires/nhbs-sex-rsk-and-substance-use-jun2010.pdf.

- 3.Colfax G, Vittinghoff E, Husnik MJ, et al. Substance use and sexual risk: a participant- and episode-level analysis among a cohort of men who have sex with men. Am J of Epidemiol. 2004;159(10):1002–1012. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drumright L, Gorbach P, Little S, Strathdee S. Associations between substance use, erectile dysfunction medication and recent HIV infection among men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(2):328–336. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9330-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koblin BA, Husnik MA, Colfax G, et al. Risk factors for HIV infection among sex who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2006;20(5):731–739. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000216374.61442.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mansergh G, Flores SA, Koblin B, Hudson SM, McKirnan DJ, Colfax GN. Alcohol and drug use in the context of anal sex and other factors associated with sexually transmitted infections: Results from a multi-city study of high-risk men who have sex with men in the USA. Sex Transm Infect. 2008;84:509–511. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.031807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Purcell DW, Parsons JT, Halkitis PN, Mizuno Y, Woods WJ. Substance use and sexual transmission risk behavior of HIV-positive men who have sex with men. J Subst Abuse. 2001;13:185–200. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(01)00072-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stueve A, O’Donnell L, Duran R, San Doval A, Geier J. Being high and taking sexual risks: findings from a multisite survey of urban young men who have sex with men. AIDS Educ Prev. 2002;14:482–495. doi: 10.1521/aeap.14.8.482.24108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carrico AW, Pollack LM, Stall RD, et al. Psychological processes and stimulant use among men who have sex with men. Drug Alcohol Depen. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.10.020. [Epub ahead of Print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carpiano RM, Kelly BC, Easterbrook A, Parsons JT. Community and drug use among gay men: The role of neighborhoods and networks. J Health Soc Behav. 2011;52(1):74–90. doi: 10.1177/0022146510395026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parsons JT, Halkitis PN, Bimbi DS. Club drug use among young adults frequenting dance clubs and other social venues in New York City. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. 2006;15(3):1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nanín JE, Parsons JT. Club drug use and risky sex among gay and bisexual men in New York City. J Gay Lesb Psychother. 2006;10(3–4):111–122. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramo DE, Grov C, Delucchi K, Kelly BC, Parsons JT. Typology of club drug use among young adults recruited using time-space sampling. Drug Alcohol Depen. 2010;107(2–3):119–127. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Colfax G, Coates T, Husnik M, et al. Longitudinal patterns of methamphetamine, popper (amyl nitrite), and cocaine use and high-risk sexual behavior among a cohort of San Francisco men who have sex with men. J Urban Health. 2005;82(0):i62–i70. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drumright LN, Patterson TL, Strathdee SA. Club drugs as causal risk factors for HIV acquisition among men who have sex with men: a review. Subst Use Misuse. 2006;41:1551–1601. doi: 10.1080/10826080600847894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grov C, Parsons JT, Bimbi DS. In the shadows of a prevention campaign: Sexual risk behavior in the absence of crystal methamphetamine. AIDS Educ Prev. 2008;20(1):42–55. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2008.20.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koblin BA, Murrill C, Camacho M, et al. Amphetamine use and sexual risk among men who have sex with men: Results from the National HIV Behavioral Surveillance study--New York City. Subst Use Misuse. 2007;42(10):1613–16128. doi: 10.1080/10826080701212519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Semple S, Zians J, Grant I, Patterson T. Sexual risk behavior of HIV-positive methamphetamine-using men who have sex with men: The role of partner serostatus and partner type. Arch Sex Behav. 2006;35(4):461–471. doi: 10.1007/s10508-006-9045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Semple S, Zians J, Strathdee S, Patterson T. Sexual marathons and methamphetamine use among HIV-positive men who have sex with men. Arch Sex Behav. 2009;38(4):583–590. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9292-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelly BC, Parsons JT, Wells B. Prevalence and predictors of club drug use among club-going young adults in New York City. J Urban Health. 2006;83(5):884–895. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9057-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parsons JT, Grov C, Kelly BC. Club drug use and dependence among young adults recruited through time-space sampling. Public Health Rep. 2009 Mar-Apr;124:246–254. doi: 10.1177/003335490912400212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pantalone DW, Bimbi DS, Holder CA, Golub SA, Parsons JT. Consistency and change in club drug use by sexual minority men in New York City, 2002 to 2007. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(10):1892–1895. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.175232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Santos G-M, Das M, Colfax G. Interventions for non-injection substance use among US men who have sex with men: What is needed. AIDS Behav. 2011;15:51–56. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9923-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mausbach BT, Semple SJ, Strathdee SA, Zians J, Patterson TL. Efficacy of a behavioral intervention for increasing safer sex behaviors in HIV-positive MSM methamphetamine users: Results from the EDGE study. Drug Alcohol Depen. 2007;87(2–3):249–257. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mansergh G, Koblin BA, McKirnan DJ, et al. An Intervention to reduce HIV risk behavior of substance-using men who have sex with Men: A two-group randomized trial with a nonrandomized third group. Plos Med. 2010;7(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morgenstern J, Bux DA, Jr, Parsons J, Hagman BT, Wainberg M, Irwin T. Randomized trial to reduce club drug use and HIV risk behaviors among men who have sex with men. J Consult Clin Psych. 2009;77(4):645–656. doi: 10.1037/a0015588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.SAMHSA. [Accessed October, 2011.];Results from the 2006 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: national findings. 2007 http://oas.samhsa.gov/nsduh/2k6nsduh/2k6results.pdf.

- 28.Watters JK, Biernacki P. Targeted sampling: Options for the study of hidden populations. Soc Problems. 1989;36:416–430. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shelton M. Gay men and substance abuse. Center City, MN: Hazelden Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cochran BN, Peavy KM, Robohm JS. Do specialized services exist for LGBT individuals seeking treatment for substance misuse? A study of available treatment programs. Subst Use Misuse. 2007;42(1):161–176. doi: 10.1080/10826080601094207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chiasson M, Parsons J, Tesoriero J, Carballo-Dieguez A, Hirshfield S, Remien R. HIV behavioral research online. J Urban Health. 2006;83(1):73–85. doi: 10.1007/s11524-005-9008-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fernández MI, Varga LM, Perrino T, et al. The Internet as recruitment tool for HIV studies: viable strategy for reaching at-risk Hispanic MSM in Miami? AIDS Care. 2004;16(8):953–963. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331292480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salyers Bull S, Lloyd L, Rietmeijer C, McFarlane M. Recruitment and retention of an online sample for an HIV prevention intervention targeting men who have sex with men: the smart sex quest project. AIDS Care. 2004;16(8):931–943. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331292507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mustanski B. Getting wired: Exploiting the internet for the collection of valid sexuality data. J Sex Res. 2001;38(4):292–301. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pequegnat W, Rosser BRS, Bowen AM, et al. Conducting internet-based HIV/STD prevention survey research: Considerations in design and evaluation. AIDS Behav. 2007;11:505–521. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9172-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Konstan JA, Simon Rosser BR, Ross MW, Stanton J, Edwards WM. The story of subject naught: A cautionary but optimistic tale of internet survey research. J Comput-Mediat Comm. 2005;10(2):00–00. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Evans AR, Wiggins RD, Mercer CH, Bolding GJ, Elford J. Men who have sex with men in Great Britain: Comparison of a self-selected internet sample with a national probability sample. Sex Transm Infect. 2007;83:200–205. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.023283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raymond H, Rebchook G, Curotto A, et al. Comparing Internet-based and venue-based methods to sample MSM in the San Francisco Bay Area. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(1):218–224. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9521-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rhodes SD, DiClemente RJ, Cecil H, Hergenrather KC, Yee LJ. Risk among men who have sex with men in the united states: A comparison of an internet sample and a conventional outreach sample. AIDS Educ Prev. 2002;14(1):41. doi: 10.1521/aeap.14.1.41.24334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ross MW, Tikkanen R, Månsson S-A. Differences between Internet samples and conventional samples of men who have sex with men: Implications for research and HIV interventions. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51(5):749–758. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00493-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsui HY, Lau JTF. Comparison of risk behaviors and socio-cultural profile of men who have sex with men survey respondents recruited via venues and the internet. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:232–242. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fisher HH, Purcell DW, Hoff CC, Parsons JT, O’Leary A. Recruitment source and behavioral risk patterns of HIV-positive men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2006;10:553–561. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9109-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grov C. HIV risk and substance use in men who have sex with men surveyed in bathhouses, bars/clubs, and on Craigslist.org: Venue of recruitment matters. AIDS Behav. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9999-6. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McKee MB, Picciano JF, Roffman RA, Swanson F, Kalichman SC. Marketing the “Sex check”: Evaluating recruitment strategies for a telephone-based HIV prevention project for gay and bisexual men. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006;18(2):116–131. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.2.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grov C, Bux D, Parsons JT, Morgenstern J. Recruiting hard-to-reach drug-using men who have sex with men into an intervention study: Lessons learned and implications for applied research. Subst Use Misuse. 2009;44(13):1855–1871. doi: 10.3109/10826080802501570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kanouse DE, Bluthenthal RN, Bogart L, et al. Recruiting drug-using men who have sex with men into behavioral interventions: A two stage approach. J Urban Health. 2005;82(1):109–119. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morgenstern J, Irwin TW, Wainberg ML, et al. A randomized controlled trial of goal choice interventions for alcohol use disorders among men who have sex with men. J Consult Clin Psych. 2007;75(1):72–84. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hatfield L, Ghiselli M, Jacoby S, et al. Methods for recruiting men of color who have sex with men in prevention-for-positives interventions. Prev Sci. 2010;11(1):56–66. doi: 10.1007/s11121-009-0149-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Barresi P, Husnik M, Camacho M, et al. Recruitment of men who have sex with men for large HIV intervention trials: Analysis of the EXPLORE study recruitment effort. AIDS Educ Prev. 2010;22(1):28–36. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2010.22.1.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bowen A. Internet sexuality research with rural men who have sex with men: Can we recruit and retain them? J Sex Res. 2005 Nov 01;42(4):317–323. doi: 10.1080/00224490509552287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Golub SA, Kowalczyk W, Weinberger CL, Parsons JT. Preexposure prophilaxis and predicted condom use among high-risk men who have sex with men. J Acq Immun Def Synd. 2010;54(5):548–555. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181e19a54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lelutiu-Weinberger C, Pachankis J, Golub S, Walker JN, Bamonte A, Parsons JT. Age cohort differences in the effects of gay-related stigma, anxiety, and identification with the gay community on sexual risk and substance use. AIDS Behav. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0070-4. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wells B, Golub SA, Parsons JT. An integrated theoretical approach to substance use and risky sexual behavior among men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(3):509–520. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9767-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meyer IH, Wilson PA. Sampling lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. J Couns Psychol. 2009;56(1):23–31. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Du Bois S, Johnson S, Mustanski B. Examining racial and ethnic minority differences among YMSM during recruitment for an online HIV prevention intervention study. AIDS Behav. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0058-0. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fernández MI, Warren JC, Varga LM, Prado G, Hernandez N, Bowen GS. Cruising in cyber space: Comparing internet chat room versus community venues for recruiting Hispanic men who have sex with men to participate in prevention studies. J Ethnicity Subst Abuse. 2007;6(2):143–162. doi: 10.1300/J233v06n02_09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jenkins RA. Recruiting substance-using men who have sex with men into HIV prevention research: Current status and future directions. AIDS Behav. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0037-5. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fisher H, Patel-Larson A, Green K, et al. Evaluation of an HIV prevention intervention for African Americans and Hispanics: Findings from the VOICES/VOCES community-based organization behavioral outcomes project. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(8):1691–1706. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9961-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fuqua V, Chen Y, Packer T, et al. Using social networks to reach Black MSM for HIV testing and linkage to care. AIDS Behav. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9918-x. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hightow-Weidman LB, Fowler B, Kibe J, et al. Healthmpowerment.org: Development of a theory-based HIV/STI website for young Black MSM. AIDS Educ Prev. 2011;23(1):1–12. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2011.23.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rausch D, Dieffenbach C, Cheever L, Fenton KA. Towards a more coordinated federal response to improving HIV prevention and sexual health among men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9908-z. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]