Abstract

(S)-2-Hydroxypropylphosphonic acid epoxidase (HppE) is an unusual mononuclear iron enzyme that catalyzes the oxidative epoxidation of (S)-2-hydroxypropylphosphonic acid ((S)-HPP) in the biosynthesis of the antibiotic fosfomycin. HppE also recognizes (R)-2-hydroxypropylphosphonic acid ((R)-HPP) as a substrate and converts it to 2-oxo-propylphosphonic acid. To probe the mechanisms of these HppE-catalyzed oxidations, cyclopropyl- and methylenecyclopropyl-containing compounds were synthesized and studied as radical clock substrate analogues. Enzymatic assays indicated that the (S)- and (R)-isomers of the cyclopropyl-containing analogues were efficiently converted to epoxide and ketone products by HppE, respectively. In contrast, the ultrafast methylenecyclopropyl-containing probe inactivated HppE, consistent with a rapid radical-triggered ring-opening process that leads to enzyme inactivation. Taken together, these findings provide, for the first time, experimental evidence for the involvement of a C2-centered radical intermediate with a lifetime on the order of nanoseconds in the HppE-catalyzed oxidation of (R)-HPP.

Keywords: epoxidase, fosfomycin biosynthesis, catalytic mechanism, cyclopropylcarbinyl radical probes

Fosfomycin ((1R, 2S)-1,2-epoxypropylphosphonic acid, 1) is a widely used broad-spectrum antibiotic with activity against both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacterial infections.1 Fosfomycin blocks bacterial cell wall biosythesis by inhibiting UDP-N-acetyl-glucosamine-3-O-enolpyruvyltransferase (MurA) through the covalent modification of an active site cysteine residue.2 A proposed biosynthetic pathway for fosfomycin was first reported in 1995.3 One of the key steps in this pathway is the formation of the epoxide ring, which is catalyzed by (S)-2-hydroxypropylphosphonic acid epoxidase (HppE), a mononuclear non-heme iron enzyme.4, 5 Unlike most epoxidases that catalyze direct oxygen atom insertion into an alkene precursor,6 the oxirane moiety of fosfomycin is generated by forming a C–O bond between C1 and the 2-OH group of the substrate (S)-2-hydroxypropylphosphonic acid (2, (S)-HPP) in a dehydrogenation reaction (Scheme 1A).3, 7 HppE catalysis employs molecular oxygen as the oxidant and consumes a stoichiometric amount of NADH as the electron donor.5, 8 18O kinetic isotope effects (KIEs) studies of HppE revealed the formation of an FeIII-OOH species in the (partially) rate-limiting step of O2 activation.9

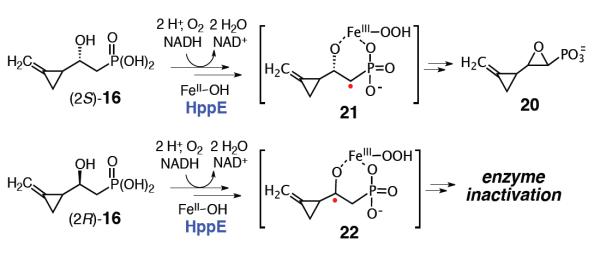

Scheme 1.

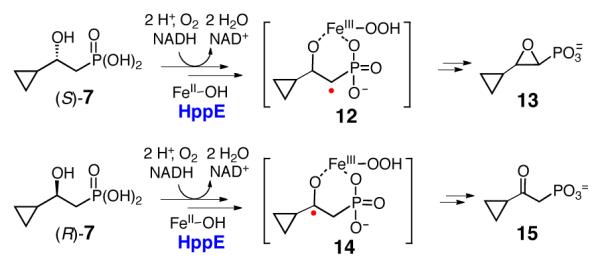

Proposed mechanism for the oxidation of (S)- and (R)-HPP by HppE. (A) Conversion of (S)-HPP (2) to fosfomycin (1). (B) Conversion of (R)-HPP (3) to 2-oxopropylphosphonic acid (4).

Interestingly, HppE can also recognize and efficiently oxidize (R)-HPP (3), the enantiomer of the natural substrate, to 2-oxopropylphosphonic acid (4) (Scheme 1B).10 The catalytic versatility and substrate flexibility of HppE suggest that both the regiochemistry of the hydrogen atom abstraction steps and the nature of the resulting radical intermediates vary with the stereochemical properties of the substrate. Crystallographic and spectroscopic experiments showed that both enantiomers of HPP (2 and 3) act as bidentate ligands to the mononuclear iron, such that only a single hydrogen atom (1-HR for 2 and 2-H for 3) is poised for abstraction by a reactive iron-oxygen species (likely FeIII-OO•).11, 12 These results led to the current working hypothesis for the mechanisms of the HppE-catalyzed reactions shown in Scheme 1.

Although non-heme iron enzymes are thought to initiate substrate oxidation via hydrogen atom abstraction, leading to the formation of substrate-derived radical intermediates,13 experimental evidence for the involvement of discrete radical intermediates in these enzymatic systems is often lacking.14 Specifically for the HppE-catalyzed reactions, the intermediacy of the proposed substrate radical species (5 and 6) has never been verified experimentally. To address this issue and gain support for the proposed reaction mechanisms, substrate analogues bearing strategically incorporated cyclopropyl or methylenecyclopropyl moieties were prepared and analyzed as mechanistic probes of HppE catalysis. The radical-induced ring opening of cyclopropylcarbinyl or methylenecyclopropylcarbinyl radicals are well known.15, 16 Thus, the detection of ring-opened turnover products or radical induced enzyme inactivation would provide evidence for the occurrence of radical intermediates during catalysis and their lifetimes. In this paper, we report the syntheses of a set of cyclopropyl- and methylenecyclopropyl-containing substrate analogues ((S)-7, (R)-7 and 16), the evaluation of these compounds as radical clock probes for the HppE reaction, and the mechanistic implications of the incubation results.

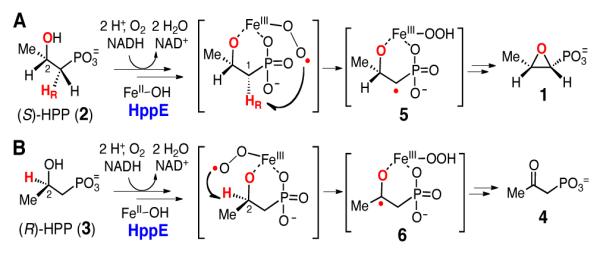

The syntheses of (S)-7 and (R)-7 are depicted in Scheme 2. Treatment of the bromo compound 817 with P(OEt)3 under Michaelis-Arbuzov reaction conditions followed by reduction of the resulting phosphonate 9 with NaBH4 gave a racemic mixture of alcohol 10. Resolution of this pair of alcohols was attempted using various lipases. This method attempts to utilize the asymmetric environment in the lipase active site to stereoselectively acetylate one of the enantiomers, rendering the resulting acetate separable from the unreacted alcohol. Unfortunately, all lipase systems tested showed poor stereoselectivity towards 10.18 However, it was later found that efficient resolution of the racemic acetate 11 could be achieved through asymmetric hydrolysis with pig liver esterase. Indeed, after three rounds of acetylation and esterasecatalyzed hydrolysis, both (R)- and (S)-10 were obtained in >94% enantiomeric excess (ee) as determined by 31P NMR analysis using quinine as a chiral shifting reagent (Figure S2.1-1).18c Subsequent deprotection of the phosphonate ethyl ester by TMSBr gave the desired substrate analogues (S)-7 and (R)-7.

Scheme 2.

Synthetic schemes for the preparation of (S)- and (R)-7.

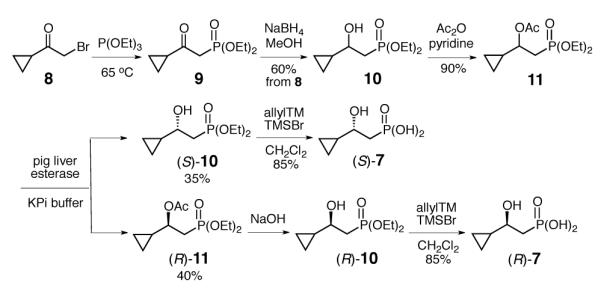

The purified (S)-7 and (R)-7 were each incubated with HppE and the reactions were monitored by 1H-NMR spectroscopy (Figure 1). Both compounds were found to be substrates of HppE and each was converted to a single product (Scheme 3). A 1,2-epoxide (13) was produced when (S)-7 was employed as the substrate, whereas a keto-product (15) was obtained from the incubation with (R)-7. The chemical nature of these products was further verified by high-resolution mass spectrometry (Figure S5-1), and the structure of 15 was also confirmed by comparison with a synthetic standard. The regio- and stereoselectivity of the turnover of (S)-7 and (R)-7 are consistent with those established for 2 and 3. Notably, the cyclopropyl group is retained in both products (13 and 15).

Figure 1.

1H-NMR end-point assay of HppE with (R)- and (S)-7. (A) Initial time point recorded 3 min after incubation of substrate with enzyme. (B) 36 min time point showing >90% conversion of (S)-7 to 13. (C) 36 min time point showing >90% conversion of (R)-7 to 15. (See Figure S4-1, S4-2 for details).

Scheme 3.

Conversion of (S)-7 to 13 and (R)-7 to 15 by HppE.

The conversion of (S)-7 to 13 is not surprising, since the putative C1 radical intermediate (12) is not expected to affect the cyclopropyl group at the C3 position. However, the conversion of (R)-7 to 15 as the sole product is in contrast to the anticipation that the C2-centered carbinyl radical (i.e. 14), once formed, would trigger ring opening of the adjacent cyclopropyl group. At first glance, this observation appears to contradict the proposed radical-mediated oxidation mechanism. However, the retention of the cyclopropyl group in the product may be ascribed to the subsequent one-electron oxidation step (14→15) being more facile than the competing ring opening reaction.

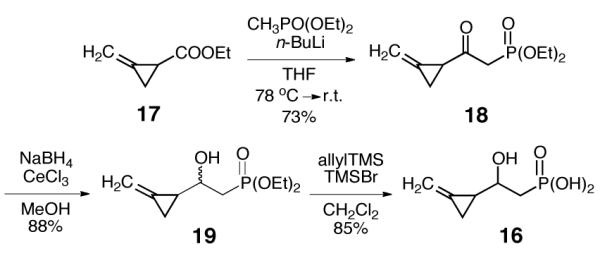

Considering that the ring opening rate constant of (methylenecyclopropyl)carbinyl radical (k = 6 × 109 s−1 at 298K)19 is nearly two-order of magnitude greater than that of the cyclopropylcarbinyl radical (k = 8.6 × 107 s−1 at 298 K),20 a substrate analogue carrying a methylenecyclopropyl group (16) was designed and synthesized as a more sensitive probe to detect the transient formation of radical intermediate by HppE. The synthetic route to 16 started with nucleophilic addition of methyldiethylphosphonate to ester 17,21 followed by Luche reduction of the resulting ketone (18) to give 19 (Scheme 4). Since attempts to resolve this racemic alcohol using various lipases and esterases failed, 19 was converted to 16 as a racemic mixture. While enantiomerically pure substrates are preferred, experiments performed with the racemic sample can still provide evidence to discern the possible formation of radical intermediates in the HppE-catalyzed reactions.

Scheme 4.

Synthetic scheme for the preparation of 16.

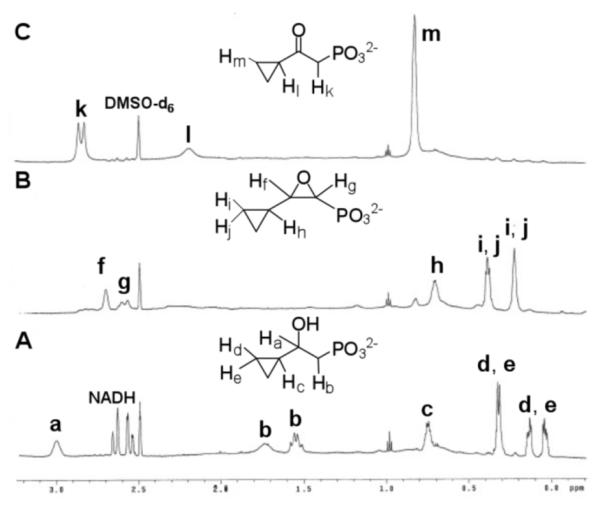

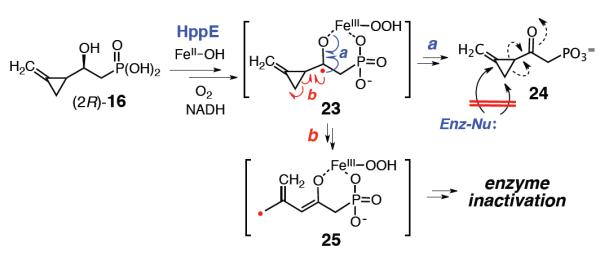

When compound 16 was incubated with HppE, formation of a new product was detected by NMR spectroscopy. However, the conversion was incomplete with no further consumption of 16 observed after ~10 min. No fosfomycin formation could be detected when the natural substrate, (S)-HPP (2), was incubated with HppE that had been pretreated with 16, suggesting that this compound (16) also inactivates the enzyme. The fact that 16 can act as both a substrate and an inactivator for HppE may simply be a consequence of the racemic nature of 16 used for these assays. Namely, the outcome of the incubation is governed by the C2 stereochemistry of 16, with one epimer serves as the substrate and the other acts as an inactivator.

The structure of the turnover product of 16 is a molecule featuring both an epoxide ring and an intact methylenecyclopropyl group. This is supported by the appearance of new peaks at 2.7–2.9 and 5.3 ppm, which are characteristic resonances for the oxiranyl protons and the olefinic protons of a terminal alkene, respectively. By analogy to the reaction with (S)-7, this product may be assigned to the corresponding 1,2-epoxyl compound 20 derived from the (2S)-epimer of 16 (Scheme 5). The presence of 20 in the reaction system was also confirmed using high resolution mass spectrometry ([M-H]− calcd for C6H8O4P−: m/z 175.0166, found: m/z 175.0160) (Figure S5-2).

Scheme 5.

Proposed reactions of (2S)- and (2R)-16 with HppE.

As (2S)-16 is likely to be a substrate of HppE, the inactivation of HppE may thus be attributed to the action of (2R)-16. Two mechanistic scenarios can be envisioned for the inactivation of HppE by the 2R-epimer of 16 (Scheme 6). In route a, 16 is first converted to the corresponding 2-oxo phosphonate 24 in a manner analogous to the oxidation of (R)-3 and (R)-7 by HppE. Since the cyclopropyl group of 24 is primed by the newly formed electron-withdrawing 2-keto functionality, it may be susceptible to the attack by an active site nucleophile in a Michael-addition reaction.22 An alternative explanation for the observed inactivation (route b) lies in the ultrafast radical-triggered ring opening of the methylenecyclopropyl group, whereby the C2 radical intermediate (25) rearranges to an allylic radical that inactivates the enzyme.

Scheme 6.

Proposed mechanisms for the inactivation of HppE by (2R)-16.

In order to distinguish between these two possibilities, the 2-keto product (24) was chemically synthesized and tested as an inhibitor of HppE activity. (S)-HPP (2) was added to the HppE reaction system that had been preincubated with an excess amount of 24 (20-fold excess than enzyme), and the enzyme activity was determined following fosfomycin formation by 1H-NMR (Figure S4-3). No difference in the rate or extent of fosfomycin formation was detected in the presence or absence of 24, clearly indicating that this putative turnover product is not an inactivator of HppE. Therefore, a mechanism initiated by a radical-triggered ring opening is a more likely mode of inactivation of HppE by (R)-17. Consistent with a radical-induced enzyme modification, HppE activity could not be restored after extensive dialysis of the inactivated enzyme. Moreover, given the differences in ring opening rates of the cyclopropylcarbinyl and methylenecyclopropylcarbinyl radicals and the fact inactivation was not observed with (R)-7, the lifetime of radical 22 can be estimated to be on the order of nanoseconds, placing it within range of a true intermediate.

In this work, cyclopropyl- and methylenecyclopropyl-based radical probes were employed to study the mechanism of HppE-catalysis. Specifically, the cyclopropyl-containing analogues (S)-7 and (R)-7 were found to be processed by HppE to epoxide 13 and ketone 15 products, respectively. Despite the presence of a cyclopropyl radical reporting group in these structures, the reactions of (S)-7 and (R)-7 are free from apparent radical-triggered ring opening events. In contrast, incubation with the ultrafast radical probe 16 led to the formation of 24 and irreversible enzyme inactivation. While product 20 is thought to be generated from (2S)-16 via C1-centered radical intermediate 21, the observed inactivation is likely a result of radical induced ring opening of the C2-centered radical intermediate (22) derived from (2R)-16. These observations are significant because they provide the first experimental evidence supporting the involvement of substrate radical intermediate(s) in an HppE-catalyzed reactions, and also allow estimation of the rate of the subsequent electron transfer step to be between 8.6 × 107 and 6 × 109 s−1 based on the ring-opening rate constants of the cyclopropylcarbinyl and methylenecyclopropylcarbinyl radicals.

Supplementary Material

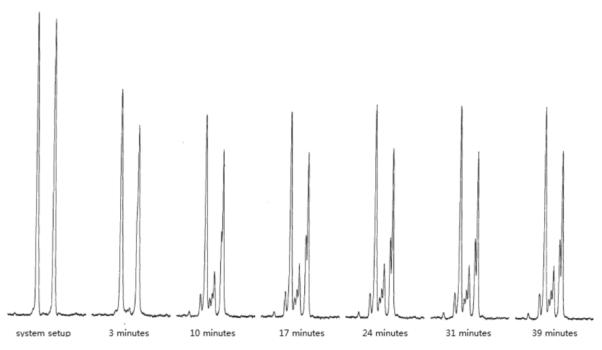

Figure 2.

1H-NMR assay of HppE with 16. Spectra were recorded at different time points. Only the region (5.1–5.4 ppm) of the olefinic protons is shown. No further consumption of 16 was observed after ~10 min.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to thank Steve Sorey for his help on acquiring the NMR spectra.

Funding Sources This work is supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (GM040541 to H.-w.L) and the Robert A. Welch Foundation (F-1511 to H.-w.L. and A-1176 to D.H.R.).

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT Supporting Information Details of synthetic methods for compounds 7, 15, 16, and 24, and experimental procedures of the enzymatic reactions of HppE with each substrate. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- (1).Raz R. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012;18:4–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2)(a).Marquardt JL, Brown ED, Lane WS, Haley TM, Ichikawa Y, Wong CH, Walsh CT. Biochemistry. 1994;47:10646–10651. doi: 10.1021/bi00201a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Eschenburg S, Priestman M, Schönbrunn E. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;280:3757–3763. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411325200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Hidaka T, Goda M, Kuzuyama T, Takei N, Hidaka M, Seto H. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1995;249:274–280. doi: 10.1007/BF00290527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Liu P, Murakami K, Seki T, He X, Yeung SM, Kuzuyama T, Seto H, Liu H.-w. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:4619–4620. doi: 10.1021/ja004153y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Liu P, Liu A, Yan F, Wolfe MD, Lipscomb JD, Liu H.-w. Biochemistry. 2003;42:11577–11586. doi: 10.1021/bi030140w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Thibodeaux CJ, Chang W, Liu H.-w. Chem. Rev. 2012;112:1681–1709. doi: 10.1021/cr200073d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7)(a).Hammerschmidt F, Bovermann G, Bayer K. Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1990:1055–1061. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hammerschmidt F. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1. 1991:1993–1996. [Google Scholar]

- (8)(a).Yan F, Munos JW, Liu P, Liu H.-w. Biochemistry. 2006;45:11473–11481. doi: 10.1021/bi060839c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Munos JW, Moon S-J, Mansoorabadi SO, Chang W, Hong L, Yan F, Liu A, Liu H.-w. Biochemistry. 2008;47:8726–8735. doi: 10.1021/bi800877v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Mirica LM, McCusker KP, Munos JW, Liu H.-w., Klinman JP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:8122–8123. doi: 10.1021/ja800265s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Zhao Z, Liu P, Murakami K, Kuzuyama T, Seto H, Liu H.-w. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2002;41:4529–4532. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20021202)41:23<4529::AID-ANIE4529>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11)(a).Woschek A, Wuggenig F, Peti W, Hammerschmidt F. Chembiochem. 2002;3:829–835. doi: 10.1002/1439-7633(20020902)3:9<829::AID-CBIC829>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Higgins LJ, Yan F, Liu P, Liu H.-w., Drennan CL. Nature. 2005;437:838–844. doi: 10.1038/nature03924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12)(a).Yan F, Moon S-J, Liu P, Zhao Z, Lipscomb JD, Liu A, Liu H.-w. Biochemistry. 2007;46:12628–12638. doi: 10.1021/bi701370e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Yun D, Dey M, Higgins LJ, Yan F, Liu H.-w., Drennan CL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:11262–11269. doi: 10.1021/ja2025728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13)(a).Kappock TJ, Caradonna JP. Chem. Rev. 1996;96:2659–2756. doi: 10.1021/cr9402034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hegg EL, Que L. Eur. J. Biochem. 1997;250:625–629. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.t01-1-00625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Rocklin AM, Tierney DL, Kofman V, Brunhuber NMW, Hoffman BM, Christoffersen RE, Reich NO, Lipscomb JD, Que L. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999;96:7905–7909. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.14.7905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Fitzpatrick PF. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1999;68:355–381. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Gibson DT, Parales RE. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2000;11:236–243. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(00)00090-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Prescott AG, Lloyd MD. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2000;17:367–383. doi: 10.1039/a902197c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Costas M, Mehn MP, Jensen MP, Que L., Jr. Chem. Rev. 2004;104:939–986. doi: 10.1021/cr020628n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Kovaleva EG, Lipscomb JD. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2008;4:186–193. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Bollinger JM, Jr., Krebs C. Curr. Opin. Chem Biol. 2007;11:151–158. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) van der Donk WA, Krebs C, Bollinger JM., Jr. Current Opinion Struct. Biol. 2010;20:673–683. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).For examples see: Ryle MJ, Liu A, Muthukumaran RB, Ho RYN, Koehntop KD, McCracken J, Jr., Que L, Hausinger RP. Biochemistry. 2003;42:1854–1862. doi: 10.1021/bi026832m.; Howard-Jones AR, Elkins JM, Clifton IJ, Roach PL, Adlington RM, Baldwin JE, Rutledge PJ. Biochemistry. 2007;46:4755–4762. doi: 10.1021/bi062314q.

- (15)(a).Griller D, Ingold KU. Acc. Chem. Res. 1980;13:317–323. [Google Scholar]; (b) Newcomb M. Tetrahedron. 1993;49:1151–1176. [Google Scholar]; (c) Silverman RB. Acc. Chem. Res. 1995;28:335–342. [Google Scholar]; (d) Newcomb M, Toy PH. Acc. Chem. Res. 2000;33:449–455. doi: 10.1021/ar960058b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Salaun J. Topics in Current Chemistry. Vol. 207. Springer-Verlag; Berlin: 2000. pp. 1–67. [Google Scholar]; (f) Ortiz de Montellano PR. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:932–948. doi: 10.1021/cr9002193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16)(a).Lenn ND, Shih Y, Stankovuch MT, Liu H.-w. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989;111:3065–3067. [Google Scholar]; (b) Lai M.-t., Li D, Oh E, Liu H.-w. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:1619–1628. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Laurent M, Ceresiat M, Marchand-Brynaert J. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2006:3755–3766. doi: 10.1021/jo030377y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18)(a).Zhang YH, Yuan CY, Li ZY. Tetrahedron. 2002;58:2973–2978. [Google Scholar]; (b) Zurawinski R, Nakamura K, Drabowicz J, Kielbasinski P, Mikolajczyk M. Biocatalytic, Tetrahedron Asymm. 2001;12:3139–3145. [Google Scholar]; (c) Żymańczyk-Duda E, Skwarczyński M, Lejczak B, Kafarski P. Tetrahedron Asymm. 1996;7:1277–1280. [Google Scholar]

- (19).Horner JH, Johnson CC, Lai MT, Lin H.-w., Martinesker AA, Newcomb M, Oh E. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1994;4:2693–2696. [Google Scholar]

- (20).Bowry VW, Lusztyk J, Ingold KU. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:5687–5698. [Google Scholar]

- (21).Lai MT, Liu LD, Liu H.-w. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:7388–7397. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Agnihotri G, He SM, Hong L, Dakoji S, Withers SG, Liu H.-w. Biochemistry. 2002;41:1843–1852. doi: 10.1021/bi0119363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.